Abstract

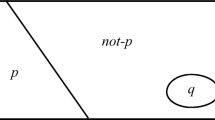

One of the most recent trends in epistemology is contrastivism. It can be characterized as the thesis that knowledge is a ternary relation between a subject, a proposition known and a contrast proposition. According to contrastivism, knowledge attributions have the form “S knows that p, rather than q”. In this paper I raise several problems for contrastivism: it lacks plausibility for many cases of knowledge, is too narrow concerning the third relatum, and overlooks a further relativity of the knowledge relation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Contrastivism about knowledge can easily be combined with an analoguous contrastivism about justification.

To be sure, few, if any, subjects are able to grasp all possible contrast propositions to a given, known proposition. For instance, someone might understand that 2 + 2 = 5 but not understand that 2 + 2 = 1/4, due to a lack of understanding of fractions (thanks to a referee here). However, that there is such a difference between "accessible" (for the subject) contrast propositions and non-accessible contrast propositions does not at all support the claim that knowledge is contrastive in the first place or that contrast propositions or a subset of them play the role the contrastivist thinks they play. Similar things hold in the case of contrast proposition which either lack a truth value or are false for non-mathematical reasons, like, e.g., “2 + 2 = Julius Caesar”.

Thanks to a referee here.

There are all kinds of differences between kinds of knowledge: e.g., some kinds of knowledge preserve information (memory), others involve the acquisition of new information (perception). Why shouldn’t there be some kinds of knowledge which are contrastive while others aren’t? This is no threat against the idea that there is a unitary relation called "knowledge". It doesn’t suggest a family resemblance or similar account of knowledge.

To be sure, Mary might know that it is going to rain rather than drizzle only given lab standards but she might know that it is going to rain rather than snow also given lay standards. The point above, however, is a different one: that she might know that p (it is going to rain), rather than q (it is not going to rain) according to some standards (relevant in non-work contexts) but not according to some other standards (relevant in lab contexts). Hence, there is more to take into account for the evaluation of knowledge attributions than contrast propositions.

The third argument slot would take n-tuples of entities of different kinds (standards, interests, contrasts, etc.) as its argument. The number of entities might vary from case to case: sometimes only a contrast proposition, sometimes only a standard, sometimes both, etc. An alternative way to go about would be to admit n additional argument places (where the value of “n” can, of course, vary; see above). This difference does not matter here. To indicate what kinds of entities could go into the third slot would be a follow-up task for the contrastivist; I cannot go any deeper into that here. Suffice it to say that, again (see footnote 4), there is no threat of theoretical disunity if one admits that the third argument slot has a disjunctive form. If there were such a threat and if knowledge could therefore not be "disjunctive" in the way indicated, then the argument in this section would be even more critical for contrastivism because it would suggest that contrastivism has unacceptable implications (that it cannot account for the unity of knowledge).

This excludes cases like the following: S does not know that Fa rather than Ga, where “F” stands for “x is a dog and Goldbach’s conjecture is true” and “G” for “x is a cat and Goldbach’s conjecture is true”.

Since this is not a definition of “knowledge”, there is no bad infinite regress looming here. – One could also put the point like this: If there is such a proposition r or s, then the correct knowledge ascription has the form of “S knows that (p or r) rather than q” or “S knows that p rather than (q or s)” or “S knows that (p or r) rather than (q or s)”.

This includes traditional sceptical hypotheses like the evil demon-hypothesis as well as more ordinary hypotheses, like the hypothesis that it is not real cheddar one is eating but something that just looks and smells like it.

|R and |S are not included in the set of contrast propositions. Suppose Sue knows that there is a dog rather than a cat. There is just one contrast proposition, namely that there is a cat. The propositions that there is a dachshund or that there is a mountain lion belong into |R and |S respectively.

Given that |R is not empty, all this also amounts to a holistic condition on knowledge: In order to know that p rather than q, S also needs to know that p rather than r (for a number of instantiations of “r”).

Perhaps there is also a loss of fit with the empirical data concerning ordinary ways of talking and thinking about knowledge. However, the two additional relativizations result from theoretical constraints within contrastivism (see above). If a lack of fit with certain kinds of data results and if that is a problem, then all the worse for contrastivism.

Some authors (cf. Hawthorne 2004, p. 29; Stanley 2005, p. 9) hold that acceptable practical reasoning requires knowledge of its premises. Whatever the connection between knowledge and practical reasoning should turn out to be, if there is one at all, then contrastivists about knowledge will also have to tell a corresponding contrastivist story about practical reasoning (cf. Sinnott-Armstrong 2004, 2006). This project, however, is problematic for reasons I cannot go into here ( but cf. my forthcoming-b for related problems concerning moral reasoning).

I am not assuming the false principle here that if F is L and F is necessary for G, then G is L. If knowledge should inherit its contrastive nature from belief, then the inheritance would have to be based on something else than the mere fact that belief is necessary for knowledge.

Thanks to Robin Cameron here.

References

Baumann, P. (forthcoming-a). Contextualism and the factivity problem. In Philosophy and Phenomenological Research.

Baumann, P. (forthcoming-b). Some problems for moral contrastivism. Comments on Sinnott-Armstrong. In Philosophical Quarterly.

Blaauw, M. (2004). Contrastivism: Reconciling skeptical doubt with ordinary knowledge, Ms.

DeRose, K. (1999). Contextualism: An explanation and defense. In J. Greco & E. Sosa (Eds.), The Blackwell guide to epistemology. Oxford: Blackwell, 187–205.

Dretske, F. (1970). Epistemic operators. Journal of Philosophy, 67, 1007–1022.

Dretske, F. (1972). Contrastive statements. Philosophical Review, 81, 411–437.

Hawthorne, J. (2004). Knowledge and lotteries. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Johnson, B. C. (2001). Contextualist swords, skeptical plowshares. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 62, 385–406.

Karjalainen, A., & Morton, A. (2003). Contrastive knowledge. In Philosophical Explorations, 6(2), 74–89.

Schaffer, J. (2005a). Contrastive knowledge. In T. S. Gendler & J. Hawthorne (Eds.), Oxford Studies in Epistemology (Vol. 1, pp. 235–271). Oxford University Press.

Schaffer, J. (2005b). What shifts? Thresholds, standards, or alternatives? In G. Preyer & G. Peter (Eds.), Contextualism in philosophy, knowledge, meaning, and truth (pp. 115–130). Oxford: Clarendon.

Sinnott-Armstrong, W. (2004). Classy pyrrhonism. In W. Sinnott-Arnstrong (Ed.), Pyrrhonian skepticism (pp. 188–207). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sinnott-Armstrong, W. (2006). Moral skepticisms. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Stanley, J. (2005). Knowledge and practical interests. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Swinburne, R. (2001). Epistemic justification. Oxford: Clarendon.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: Contrastive Beliefs?

Appendix: Contrastive Beliefs?

What about contrastivism about beliefsFootnote 14? If belief is contrastive, then perhaps knowledge derives its contrastive nature from belief?Footnote 15 The thesis would be that belief, too, is a ternary relation between a subject, a proposition believed and a contrast proposition. Sentences of the form “S believes that p” would be elliptical for sentences of the form “S believes that p rather than q” (where “rather than q” is, of course, not part of the content of the belief). Sue might believe that she is seeing a dog rather than that she is seeing a cat but she might not believe that she is seeing a dog rather than that she is seeing a wolf. Is this unorthodox view about the nature of belief plausible?

Let us start with the uncontroversial idea that an acceptable account of belief must allow for an account of the truth conditions of beliefs. If one thinks of beliefs in the usual way—as a dyadic relation between a person and a proposition, then it is easy to give truth conditions for beliefs. It works according to the following schema:

The belief that p is true iff p.

There is a principle at work here which is analogous to disquotation principles for sentences: Skip “the belief that” on the left side of “is true iff” and you get the right hand side of the bi-conditional (assuming that the meta-language contains the object-language).

How does this work in the case of contrastive belief? One might think of something like the following schema:

The belief that p rather than q is true iff p rather than q.

A principle resembling the above “disquotation” principle has been used but now with a weird result: We don’t understand what kind of condition that is and what the right-hand side of the conditional means. What does it mean to say that “p rather than q”? One way to go would be to extend contrastivism to truth. Truth would be contrastive insofar as truth conditions (for sentences, beliefs, etc.) are themselves contrastive. I wouldn’t choose this option: It is hard if not impossible to make any sense of this idea. Apart from all that ,”rather than q” is not part of the content of the belief and for that reason one might not want to include it in the “disquotation”.

Perhaps we need to modify the disquotation principle for contrastive belief in the following way:

The belief that p rather than q is true iff p.

But this also leads to several problems: The belief that p rather than q would have the same truth conditions as the belief that p rather than r.Footnote 16 The belief that the book is red rather than blue would have the same truth conditions as the belief that the book is red rather than yellow. How could these two beliefs have the same truth conditions if they are substantially different beliefs? I am not suggesting that truth conditions alone individuate beliefs. Rather, I am suggesting that quite different beliefs should not be expected to share their truth conditions.

There is also another problem. It seems possible that S has two beliefs:

-

The belief that p rather than q

-

and

-

The belief that q rather than r,

-

such that “p” and “q” cannot, of course, both be true.

-

Here is an example:

-

Fred believes that Jack stole the bike (p) rather than Jill stole the bike (q),

-

but it is also the case that

-

Fred believes that Jill stole the bike (q) rather than Jill stole the car (r).

Let us assume here that only one theft has occurred. What would be the truth conditions of these two beliefs according to the modified disquotation principle? The first belief is true iff p whereas the second belief is true iff q. So far, so good, one might say. But really, so far so bad: p and q cannot both be true because q is a contrast proposition for p. On the other hand, the two beliefs do not seem contradictory or mutually inconsistent. But how can their truth conditions then be mutually incompatible?

The overall conclusion is clear: Even if you are a contrastivist about knowledge you shouldn’t be a contrastivist about belief.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Baumann, P. Contrastivism Rather than Something Else? On the Limits of Epistemic Contrastivism. Erkenn 69, 189–200 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10670-008-9111-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10670-008-9111-4