Abstract

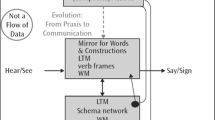

My hypothesis is that the cognitive challenge posed by death might have had a co-evolutionary role in the development of linguistic faculties. First, I claim that mirror neurons, which enable us to understand others’ actions and emotions, not only activate when we directly observe someone, but can also be triggered by language: words make us feel bodily sensations. Second, I argue that the death of another individual cannot be understood by virtue of the mirror neuron mechanism, since the dead provide no neural pattern for mirroring: this cognitive task requires symbolic thought, which in turn involves emotions. Third, I describe the symbolic leap of the human species as a cognitive detachment from the here and now, allowing displaced reference: through symbols the human mind can refer to what is absent, possible, or even impossible (like the presence of a dead person). Such a detachment has had a huge adaptive impact: adopting a coevolutionary standpoint can help explain why language is as effective as environmental inputs in order to stimulate our bodily experience. In the end I suggest a further coevolutionary “reversal”: if language is necessary to understand the death of the other, it might also be true that the peculiar cognitive problem posed by the death of the other (the corpse is present, but the other is absent) has contributed to the crucial transition from an indexical sign system to the symbolic level, i.e., the “cognitive detachment”. Death and language, as Heidegger claimed, have an essential relation for humans, both from an evolutionary and a phenomenological perspective: they have shaped the symbolic consciousness that make us conceive of them.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The ancestor of all questions of this kind is Thomas Nagel’s “What is it Like to be a Bat?” (1974).

A few clarifications are needed. (1) The brain areas involved in Tania Singer’s experiments are different from those where Rizzolatti found mirror neurons, but the general functioning is very similar in both cases: Rizzolatti himself refers to it as a “mirror mechanism,” in order to support his claims. (2) The crucial aspect I just mentioned is not a major concern in Singer’s experiment, which focuses on the different activation of the pain matrix when pain is mirrored rather than directly experienced. (3) The way by which the message is conveyed is an arbitrary signal (a warning light, a buzzer, etc.): linguistic communication is considered too empathy-oriented (moreover, the meaning of the arbitrary signal must have been set in advance through language).

Taking into consideration the metaphorical and philosophical entailments of the term “mirror” in the expression “mirror neurons,” is one of the main goals of this paper.

A few researchers have tackled these aspects. Vittorio Gallese, who played a major role in the discovery of mirror neurons, has studied the correlation between linguistic comprehension and the activation of neural structures of the mirror system. Several experiments showed that the processing of sentences describing actions causes the activation of premotor cortex areas which extensively overlap with the areas which control the related motor acts. Therefore, in order to interpret the sentence “X raises his hand” I trigger a neural event similar to that triggered when I myself raise my hand (and also similar, according to other experiments, to that triggered when I observe someone raising a hand). This drives Gallese to sketch a connection between mirror neurons’ system and language, thanks to a foundation on the same neural structures. Then he can express his “neural exploitation hypothesis,” which outlines the derivation of linguistic faculties, via exaptation from neural structures originally dedicated to sensorimotor integration. For a more detailed explanation, with a survey of several experiments, see Gallese (2008), and Gallese and Lakoff (2005). Toward the end of my paper I expose other remarks on Gallese’s stimulating hypothesis, and I will try to spot an akin research pathway which seems to me still unexplored.

We will see below how these different circumstances are connected, and in which way they delineate a co-evolutionary process.

It is worth saying that the issue of empathic comprehension should not be automatically linked to an uplifting perspective, or to a vague sentimentalism, as is often the case. The discourse would be equally effective if, instead of the involvement in front of a dying friend, we were talking about the sadistic torturer who torments his or her victim to death: the pleasure he or she gets is embedded in the preliminary intuition of the sorrow that the victim is experiencing.

According to Marc Hauser, Noam Chomsky and Tecumseh Fitch, the core property which differentiates human language from animal communication is recursion that is the capability to generate an infinite array of discrete expressions with a finite set of elements. The symbolic use of signs «detached from the here and the now» is also mentioned, but not with the same emphasis as recursion (Hauser, Chomsky, and Fitch 2002: 1576). I am persuaded that these two aspects are more interconnected than it appears, and I hope to show it in future occasions.

Of course it would be incautious to match this semiotic leap with a single event, as if it were the discovery of a specific individual. Anyway, as Luca Cavalli Sforza claims, it is very likely that the development of a language is the reason for the huge evolutionary success of a small group of humans that originally came from Eastern Africa, whereas other groups living at the same age (such as the European Neanderthal) soon disappeared (see Cavalli Sforza 2004: 17, and Donald 1991/2005: 203–204).

Perhaps my interpretation of Damasio’s ‘story’ is too literal. Nevertheless, it is worth asking why this word serves so well his theoretical purposes. Also the hypothesis of the “as if” circuit is based on a logic which encompasses linguistic narration in the fullest sense: my somatosensory maps are altered by experiences which do not affect directly my perceptual apparatus, but can occupy my cognitive processing as sequences of events/actions/emotions coded in linguistic terms.

This does not imply that the stimulation is identical, it only concerns the same structures and reveals a commonality of function.

As in the case of Damasio’s ‘story,’ the interpretation of Rizzolatti’s ‘vocabulary’ might appear too literal. Nevertheless, some statements by Gallese seem to go in the same direction: “According to the neural exploitation hypothesis, the ‘words’ of the premotor vocabulary (Rizzolatti et al. 1988) are not only assembled and chained to form intentional ‘action sentences’ (see the discussion of the MNS [Mirror Neurons’ System] and action intentions); they can also be assembled and chained to structure language sentences and thoughts” (Gallese 2008: 328).

This new frame of functioning is what I have defined elsewhere by the expression “post-symbolic corporeity” (Berta 2009). I am currently writing a book to explain how this upgraded corporeity, proceeding from the double disjunction sign/referent and sensation/stimulus, works and affects our modes of experience.

The archeological traces of this struggle to deal with the question of death (burying, in the first place) are those which date back to the origin of culture conceived of as the way our species has been trying to inhabit this planet. It would be interesting to cross these finds with the paleo-anthropological conjectures on the origin of language. A hint at this issue, though in a different framework, can be found in Philip Lieberman (1998: 139).

A consonance with these hypotheses can be traced in some questions posed by Dennett: “What role, if any, does language play in this? Are we the only species of mammal that buries its dead because we’re the only species that can talk about what we share when we confront a fresh corpse? Do the burial practices of Neanderthals show that they must have had fully articulate language? These are among the questions we should try to answer. […] Was our virtuosity as natural psychologists a prerequisite for our linguistic ability, or is it the other way around: did our use of language make our psychological talents possible? This is another controversial area of current research, and probably the truth is, as it so often is, that there was a coevolutionary process, with each talent feeding off the other” (2006: 113).

Trying to extend our sight as far as to incorporate the opposite perspective, we might say that death has shaped the symbolic mind, which in turn “invented” death. Of course this does not imply that, if the problem of death facilitated the access to the symbolic functioning, the striking effects of cognitive retroaction related to this access were causally dependent on death itself.

Robert Worden claims that these cognitive features are all that is needed, from the evolutionary, neurophysiological and computational standpoint, to account for the origin of language: “Social intelligence and a theory of mind are vital pre-requisites for language. I propose that language is not just a new mental faculty which uses these two, but is a direct application of them” (1998: 149).

According to Jan Assmann, “Man, fallen out of nature for too much knowledge, must create an artificial world in which he can live. This world is culture. Culture originates from the conscious awareness of death and of being mortal” (2000: 5; my translation).

John Tooby and Leda Cosmides argue that fitness-enhancing strategies do not solely involve direct action on the external world (as in the cases I have just mentioned), but also include adaptive changes to the body, and to the brain/mind (e.g., play, learning, perhaps dreaming): “Building the brain, and readying each of its adaptations to perform its function as well as possible is, we believe, a vastly underrated adaptive problem” (2001: 14). This last category encompasses universal human habits with no apparent adaptive aim, such as aesthetically driven behaviours.

For a survey, which also tries to sort out some criteria of scientific validity, see Számadó and Szathmáry (2006).

I am sketching out very briefly the scenario imagined by Chris Knight, who indeed does not refer to the issue of death. He suggests that the origin of this intra-group cohesion may derive from the coalition of females interested in securing food supply during the long period dedicated to parental duties (Knight 1998).

See Cosmides and Tooby (2000). This seminal paper focuses on decoupling and meta-representations, though it does not explicate the role of language and symbolic thought in those cognitive mechanisms.

For some insights into the relationship between death and consciousness, please see Lanier (1997).

References

Assmann, J. (2000). Der Tod als Thema der Kulturtheorie. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp Verlag.

Berta, L. (2009). Narrazione e neuroni specchio. In S. Calabrese (Ed.), Neuronarratologia (pp. 187–203). Bologna: ArchetipoLibri.

Cavalli Sforza, L. L. (2004). L’evoluzione della cultura. Milan: Codice.

Cosmides, L., & Tooby, J. (2000). Consider the source: the evolution of adaptations for decoupling and metarepresentation. In D. Sperber (Ed.), Metarepresentations: A multidisciplinary perspective (pp. 53–115). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Damasio, A. (2003). Looking for Spinoza: Joy, sorrow, and the feeling brain. New York: Harcourt.

Deacon, T. (1998). The symbolic species: The co-evolution of language and the brain. New York: Norton.

Dennett, D. C. (1991). Consciousness explained. Boston: Little, Brown & Co.

Dennett, D. C. (2006). Breaking the spell. Religion as a natural phenomenon. New York: Penguin.

Donald, M. (1991/2005). Origins of the modern mind: Three stages in the evolution of culture and cognition. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Gallese, V. (2008). Mirror neurons and the social nature of language: The neural exploitation hypothesis. Social Neuroscience, 8, 317–333.

Gallese, V., & Lakoff, G. (2005). The brain’s concepts: The role of the sensorimotor system in reason and language. Cognitive Neuropsychology, 22, 455–479.

Hauser, M. D., Chomsky, N., & Fitch, W. T. (2002). The faculty of language: What it is, who has it, and how did it evolve? Science, 298, 1569–1579.

Heidegger, M. (1959/1982). On the way to language. San Francisco: Harper.

James, W. (1884). What is an emotion? Mind, 9, 188–205.

Knight, Ch. (1998). Ritual/speech coevolution: A solution to the problem of deception. In J. R. Hurford, M. Studdert-Kennedy, & Ch. Knight (Eds.), Approaches to the evolution of language. Social and cognitive bases (pp. 68–91). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kosslyn, S. (1995). Mental Imagery. In S. Kosslyn & D. Osherson (Eds.), Visual cognition (pp. 267–296). Cambridge: MIT Press.

Lanier, J. (1997). Death: the skeleton key of consciousness studies? Journal of Consciousness Studies, 4(2), 181–185.

Lévinas, E. (2000). God, death, and time. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Lieberman, Ph. (1998). Eve spoke. Human language and human evolution. New York: Norton.

Nagel, Th. (1974). What is it like to be a bat? The philosophical review, LXXXIII(4), 435–450.

Rizzolatti, G., & Sinigaglia, C. (2008). Mirrors in the brain: How our minds share actions, emotions, and experience. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Rizzolatti, G., Camarda, R., Fogassi, M., Gentilucci, M., Luppino, G., & Matelli, M. (1988). Functional organization of inferior area 6 in the macaque monkey: II. Area F5 and the control of distal movements. Experimental Brain Research, 71, 491–507.

Singer, T., Seymour, B., O’Doherty, J., Kaube, H., Dolan, R. J., & Frith, Ch. D. (2004). Empathy for pain involves the affective but not sensory components of pain. Science, 303, 1157–1162.

Számadó, S., & Szathmáry, E. (2006). Selective scenarios for the emergence of natural language. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 21, 555–561.

Tooby, J., & Cosmides, L. (2001). Does beauty build adapted minds? Towards an evolutionary theory of aesthetics, fiction, and the arts. SubStance, 94(95), 6–27.

Wicker, B., Keysers, C., Plailly, J., Rovet, J. P., Gallese, V., & Rizzolatti, G. (2003). Both of us disgusted in my insula: The common neural basis of seeing and feeling disgust. Neuron, 40, 655–664.

Worden, R. (1998). The evolution of language from social intelligence. In J. R. Hurford, M. Studdert-Kennedy, & Ch. Knight (Eds.), Approaches to the evolution of language. Social and cognitive bases (pp. 148–166). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Berta, L. Death and the Evolution of Language. Hum Stud 33, 425–444 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10746-011-9170-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10746-011-9170-4