Abstract

The greatest challenge for Cultural Selection Theory lies is the paucity of evidence for structural mechanisms in cultural systems that are sufficient for adaptation by natural selection. In part, clarification is required with respect to the interaction between cultural systems and their purported selective environments. Edmonds et al. have argued that Cultural Selection Theory requires simple, conclusive, unambiguous case studies in order to meet this challenge. To that end, this paper examines the songs of the Rufous-collared Sparrow, which seem to exhibit cultural adaptations minimizing signal degradation relative to local environments. Specifically, the more forested the habitat, the more the tail end of the song resembles a whistle rather than a trill; yet, variation in song is uncorrelated with genetic variation. This paper explores the mechanisms responsible for these putative acoustic adaptations through a series of computer simulations. The main point of this research is not to test this model, but to demonstrate that models of this type have the resources to meet the in-principle objections that have been raised against Cultural Selection Theory. This research lends much-needed empirical support to Cultural Selection Theory by clarifying the nature of the interaction between culture and environment. It also contributes to evolutionary theory by clarifying the scope and limits of adaptation by natural selection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For a compelling defense of memetics, see Gers (2008).

A version of this simulation (Rand and Wilensky 2007) can be run online at: ccl.northwestern.edu/netlogo/models/ElFarol.

See Anderson (2009) for an enlightening discussion of the relationship between strategic thinking and Cultural Selection Theory.

It would be more precise to use the terms open habitat and closed habitat instead of field and forest, respectively. This is because the key factor is how much vegetation exists in the region. So, for example, a marsh might have the same acoustic properties as a field, as would the top of a body of water: all of these are open habitats in the acoustically relevant sense. Furthermore, the distinction between open and closed habitats is more precisely conceived as lying on a continuum. So, for example, the leafy treetops of a mature forest would be a very acoustically closed environment, while the floor of that mature forest might be slightly more open, a sapling forest might be more open still, and a clearing still more open than this. Moreover, the observed correlation in bird song type matches this gradient in habitat type very closely such that the more open the habitat, the more the song resembles a trill rather than a whistle. Thus, when I use the terms field and forest, it is in a slightly stylized sense that is intended to make this paper more readable.

Degradation refers to distortions of the signal’s frequency and amplitude modulations caused by environmental obstacles. It is one of two kinds of signal loss that occurs as a sound is transmitted. The other is attenuation, which is the opposite of amplification.

Interestingly, Brown and Handford learned [first by computer simulation (1996) and then by field experiment (2004)], that a further refinement of the concept of acoustic degradation is required—a distinction between average and consistent transmission fidelity. Whistles incur less average degradation than trills in both forests and fields; however, trills transmit more consistently than whistles in fields. This leads them to conclude that consistency and average transmission fidelity might produce competing selection pressures that together produce the observed correlation between song and habitat type. To avoid charges of Panglossianism, however, it would be necessary to test this new hypothesis further; for example, by verifying the relative effect of average versus consistent transmission fidelity on the song imitation of sparrows.

This description presumes that trills and whistles are distinct, rather than appearing on a continuum. This simplifying assumption will be discussed later in the paper.

By Gould and Lewontin’s description of Panglossianism, it would appear that this fallacy is frequently committed in evolutionary biology. Panglossianism is most accurately portrayed as occurring on a spectrum, where most of the transgressions are mild in degree. Adaptationist reasoning is an essential methodological device in evolutionary biology. Gould and Lewontin’s Panglossianism paper is most compellingly construed as a warning against a certain potential for inappropriate adaptationist reasoning which can occur when researchers relax their vigilance: an ideal limit of a lurking tendency all evolutionists need to avoid.

Alexander and Skyrms refer to this imitation-based dynamic as imitate-the-best.

In standard Evolutionary Game Theory, the probability a player has of playing against a particular strategy is given by the proportion of the population playing that strategy. This proportion changes over successive rounds of the game by the replicator dynamics: the proportion of the population playing a given strategy in one generation is multiplied by a fitness factor, which is the ratio of the average payoff of that strategy to the average payoff of the population.

According to Nash’s (1950) definition, distributive justice holds when two criteria are met: all the players have equal outcomes and there are no alternatives under which all players are better off. For instance, in the Prisoner’s Dilemma, distributive justice holds only when both players cooperate.

My simulations use the program NetLogo (Wilensky 1999), which can be downloaded for free at: http://ccl.northwestern.edu/netlogo.

Technically, the key interaction between players occurs only when new neighbours are introduced into a neighbourhood, but analytically there is no difference between this and a fixed-player game.

Currently territories on the far edge of the game-space share borders with those on the opposite edge, similar to the design of old arcade games: for example, if you took Pac-Man out the door on the right edge of the board, he would reappear through the door on the left edge.

Of course, some human communications show characteristics of acoustic adaptation similar to those of the Rufous-collared Sparrow; for instance, yodels and other vocal signals intended for transmission of information over long distances. It is challenging to make a case that these human calls are the result of cultural selection for several reasons. Humans can update their communication strategies throughout the course of their lives which makes it difficult to identify population frequencies of their cultural units. Further, any cultural evolutionary analysis would have to accommodate the clear potential that human strategic reasoning contributed significantly to the development of such acoustically effective calls. For these reasons, the identification and measurement of selection pressures is much more challenging in human versus bird cultural systems.

References

Alexander J, Skyrms B (1999) Bargaining with neighbours: is justice contagious? J Philos 96(11):588–598

Anderson C (2008) Sophisticated selectionism as a general theory of knowledge. Biol Philos 23:229–242

Anderson C (2009) Splitting the replicator: generalized Darwinism and te place of culture in Nature. J Evol Econ (forthcoming)

Arthur WB (1994) Inductive reasoning and bounded rationality. Am Econ Rev 84:406–411

Aunger R (ed) (2000) Darwinizing culture: the status of memetics as a science. Oxford UP, Oxford

Aunger R (2006) Culture evolves only if there is cultural inheritance. Behav Brain Sci 29(4):347–348

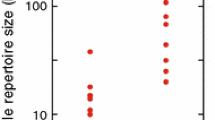

Beecher MD, Stoddard PK et al (1996) Repertoire matching between neighbouring song sparrows. Anim Behav 51:917–923

Beecher MD, Campbell SE, Nordby JC (2000) Territory tenure in song sparrows is related to song sharing with neighbours, but not to repertoire size. Anim Behav 59:29–37

Best ML (1997) Models for interacting populations of memes: Competition and niche behavior. J Memet 1

Boyd R, Richerson PJ (1985) Culture and the evolutionary process. U Chicago P, Chicago

Boyd R, Richerson PJ (2005) The origin and evolution of cultures. Oxford UP, Oxford

Brown TJ, Handford P (1996) Acoustic signal amplitude patterns: a computer simulation investigation of the acoustic adaptation hypothesis. Condor 98:608–623

Brown TJ, Handford P (2000) Sound design for vocalizations: quality in the woods, consistency in the fields. Condor 102:81–92

Burnell K (1998) Cultural variation in savannah sparrow, Passerculus sandwichensis, songs: an analysis using the meme concept. Anim Behav 56:995–1003

Burt JM, Campbell SE, Beecher MD (2001) Song type matching as threat: a test using interactive playback. Anim Behav 62(6):1163–1170

Catchpole CK (1982) The evolution of bird sounds in relation to mating and spacing behaviour. In: Kroodsma DE, Miller EH, Ouellet H (eds) Acoustic communication in birds. Academic, Toronto

Cavalli-Svorza LL, Feldman MW (1981) Cultural transmission and evolution. Princeton, Princeton

Crozier GKD (2008) Reconsidering Cultural Selection Theory. Br J Philos Sci 59(3):455–479

Dawkins R (1976) The selfish gene, 2nd edn, 1989. Oxford, New York

Dawkins R (1983) Universal Darwinism. In: Bendall DS (ed) Evolution from molecules to men. Cambridge, Cambridge

Dawkins R (1993) Viruses of the mind. In: Dahlbom B (ed) Dennett and his Critics. Blackwell, Oxford

Dennett DC (1995) Darwin’s dangerous idea: evolution and the meanings of life. Touchstone, New York

Dirlam DK (2003) Competing memes analysis. J Memet 7

Edmonds B (1998) On modeling in memetics. J Memet 2

Edmonds B (2005) The revealed poverty of the gene-meme analogy: why memetics per se has failed to produce substantive results. J Memet 9

Fitch TW (2009) Birdsong normalized by culture. Anim Behav 459(28):519–520

Gardner M (2000) Kilroy was here. Review of the meme machine by SJ Blackmore. Los Angeles Times 5 March 2000

Gers M (2008) The case for memes. Biol Theory 3(4):305–315

Gould SJ, Lewontin R (1979) The spandrels of San Marco and the Panglossian paradigm: a critique of the adaptationist programme. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 205:581–598

Gray RD, Atkinson QD (2003) Language-tree divergence times support the Anatolian theory of Indo-European origin. Nature 426(27):435–439

Gray RD, Jordan FM (2000) Language trees support the express-train sequence of Austronesian expansion. Nature 405(29):1052–1055

Handford P (1981) Vegetational correlates of variation in the song of Zonotrichia capensis. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 8:203–206

Handford P (1983) Continental pattern of morphological variation in a South American sparrow. Evolution 37(5):920–930

Handford P (1988) Trill rate dialects in the rufous-collared sparrow, Zonotrichia capensis, in northwestern Argentina. Can J Zool 66:2658–2670

Handford P, Lougheed SC (1991) Variation in duration and frequency characters in the song of the rufous-collared sparrow, Zonotrichia capensis, with respect to habitat, trill-dialects and body size. Condor 93:644–658

Handford P, Nottebohm F (1976) Allozymic and morphological variation in population samples of rufous-collared sparrows, Zonotrichia capensis, in relation to vocal dialects. Evolution 30:802–817

Henrich J, Boyd R, Richerson PJ (2008) Five misunderstandings about cultural evolution. Hum Nat 19:119–137

Holden CJ (2002) Bantu language trees reflect the spread of farming across sub-Saharan Africa: a maximum-parsimony analysis. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 269:793–799

Hopp SL, Morton ES (1998) Sound playback studies: design and analysis. In: Hopp SL, Owren MJ, Evans CS (eds) Animal acoustic communication: sound analysis and research methods. Springer, Berlin

Hull DL (2000) Taking memetics seriously: memetics will be what we make it. In: Aunger R (ed) Darwinizing culture: the status of memetics as a science. Oxford, Oxford

Hull D (2001) Chapter 8. In: Heyes C, Hull D (eds) Selection theory and social construction: the evolutionary naturalistic epistemology of Donald T. Campbell. SUNY, Albany

Kopuchian C, Lijtmaer D, Tubaro P, Handford P (2004) Temporal stability and change in a microgeographic pattern of song variation in the rufous-collared sparrow. Anim Behav 68(3):551–559

Kroodsma DE, Miller EH (eds) (1996) Ecology and evolution of acoustic communication in birds. Cornell, Ithaca

Kroodsma DE, Miller EH, Ouellet H (eds) (1982) Acoustic communication in birds. Academic, Toronto

Lougheed SC, Handford P, Baker AJ (1993) Mitochondrial DNA hyperdiversity and vocal dialects in a subspecies transition of the rufous-collared sparrow. Condor 85:889–895

Lynch A (1996) The population memetics of birdsong. In: Kroodsma DE, Miller EH (eds) Ecology and evolution of acoustic communication in birds. Cornell, Ithaca

Mesoudi A, Whiten A, Laland KN (2006) Towards a unified science of cultural evolution. Behav Brain Sci 29(4):329–383

Morton ES (1987) The effects of distance and isolation on song-type sharing in the Carolina wren. Wilson Bull 99:601–610

Nash J (1950) The bargaining problem. Economectrica 18:150–162

Nordby JC, Campbell SE, Beecher MD (1999) Ecological correlates of song learning in song sparrows. Behav Ecol 10(3):287–297

Nottebohm F (1975) Continental pattern of song variability in Zonotrichia capensis: some possible ecological correlates. Am Nat 109:605–624

Nydegger RV, Owen G (1974) Two-person bargaining: an experimental test of the Nash axioms. Int J Game Theory 3:239–250

Rand W, Wilensky U (2007) El Farol model. NetLogo. Center for Connected Learning and Computer-Based Modeling, Northwestern University, Evanston. Available at: http://ccl.northwestern.edu/netlogo/models/ElFarol

Rogers DS, Ehrlich PR (2008) Natural selection and cultural rates of change. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105(9):3416–3420

Roth A, Malouf M (1979) Game theoretic models and the role of information in bargaining. Psychol Rev 86:574–594

Tubaro PL, Segura ET, Handford P (1993) Geographic variation in the song of the rufous-collared sparrow in eastern Argentina. Condor 95:588–595

Van Huyck J, Batallio R, Mathur S et al (1995) On the origin of convention: evidence from symmetric bargaining games. Int J Game Theory 24:187–212

Wilensky U (1999) NetLogo. Center for Connected Learning and Computer-Based Modeling. Northwestern University, Evanston. Available at: http://ccl.northwestern.edu/netlogo

Wiley RH, Richards DG (1982) Adaptations for acoustic communication in birds: sound transmission and signal detection. In: Kroodsma DE, Miller EH, Ouellet H (eds) Acoustic communication in birds. Academic, Toronto

Wimsatt WC (1999) Genes, memes and cultural heredity. Biol Philos 14:279–310

Acknowledgments

Special thanks go to the following people for their help in developing the ideas in this paper: Wayne Myrvold, Bill Wimsatt, Bill Harper, Bob Batterman, Scott McDougall-Shackleford, Matt Gers, Paul Handford, Chris Hajzler, Andrew Fenton, Dale Jamieson, Laura Franklin Hall, Bill Ruddick, Greg Bognar, Chris Schlottmann, Sandra Larsen, Kim Sterelny, and two anonymous reviewers. I am also grateful for feedback received from participants in the conference “Biological Explanations of Behavior: Philosophical Perspectives” which was organized in Hannover, Germany, by Katherine Plaisance and Thomas Reydon, with special thanks to Colin Allen, David Sloan Wilson, Omri Tal, and Armin Shulz. Of course, the author maintains full responsibility for any errors or omissions that may remain in this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Crozier, G.K.D. A formal investigation of Cultural Selection Theory: acoustic adaptation in bird song. Biol Philos 25, 781–801 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10539-010-9194-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10539-010-9194-6