Abstract

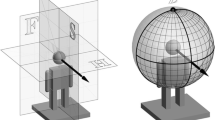

Two theses appear to be central to Reid’s view of the visual field. (1) By sight, we do not originally perceive depth or linear distance from the eye. (2) By sight, we originally perceive the position that points on the surface of objects have with regard to the centre of the eye. In different terms, by sight, we originally perceive the compass direction and degree of elevation of points on the surface of objects with reference to the centre of the eye. I consider various problems about distance perception and perception of position with regard to the centre of the eye raised by Reid’s texts. These questions are relevant to Reid’s description of the geometry of visibles as the “intrinsic” geometry of the surface of the sphere.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

See Reid (1997), VI.9: 103–112.

Among the visible appearances of objects (the appearances of objects to the eye), Reid distinguishes (1) the visible appearances of colours reflected from the surface of objects and (2) the two-dimensional visible appearances of the figures and magnitudes of three-dimensional objects at a distance: see Reid (1997), VI.4: 83–85. The use of the term “appearance” for visible figure and its magnitude does not make them sensations or modifications of the mind (on the contrary, the appearances of colour are sensations in the mind). Visible figure, a Reid claims, is real and external to the eye: “the visible figure of bodies is real and external object to eye as the tangible figure is to the touch” (Reid 1997, VI.8: 101/25). On the question of the compatibility between direct realism and Reid’s notion of visible figure, see Grandi (2006), Nichols (2002), Nichols (2007), pp. 109–142, Van Cleve (2002), Yaffe (2002).

See also Reid (1997), VI.9.

The expression “purely visual observer” to denote the case of the being endowed only with sight and the Idomenian has been introduced by Weldon (1978).

See Reid (1997), VI.9: 106–112.

On the constancy hypothesis, see Pastore (1971), pp. 11–13. On p. 11, Pastore says: “The content of the constancy hypothesis in reference to spatial characteristics refers to the conformity or correspondence of spatial attributes of original perception and the retinal image”.

In the Essays on the Intellectual Powers of Man, Reid explains the status of visible figure in this way: “[W]hen I use the names of tangible and visible space, I do not mean to adopt Bishop BERKELEY’s opinion, so far as to think that they are really different things, and altogether unlike. I take them to be different conceptions of the same thing; the one very partial, and the other more complete; but both distinct and just, as far as they reach (Reid 2002, II.19: 222/37–223/2). Later on, in the same chapter, Reid adds: “Our sight alone, unaided by touch, gives a very partial notion of space, but yet a distinct one. When it is considered, according to this partial notion, I call it visible space. The sense of touch gives a much more complete notion of space; and when it is considered according to this notion, I call it tangible space. Perhaps there may be intelligent beings of a higher order, whose conceptions of space are much more complete than those we have from both senses. Another sense added to those of sight and touch, might, for what I know, give us conceptions of space, as different from those we can now attain, as tangible space is from visible; and might resolve many knotty points concerning it, which, from the imperfection of our faculties, we cannot by any labour untie” (Reid 2002, II.19: 223/13–24). The “man endowed only with sight” includes straightness in the dimension of left-and-right (or up-and-down) in his notion of straight line (that is, he excludes curvature in the dimension of right-and-left or up-and-down). But he does not either include or exclude curvature in the backward-and-forward dimension of which he is not aware (see Reid 1997, VI.9: 107/5–30).

Reid distinguishes perfect vision and distinct vision: “We ought therefore to distinguish between perfect Vision and distinct Vision calling that perfect Vision where the Rays from one point of the Object do meet in one point of the Retina & calling that Distinct Vision where the Radius of Dissipation bears but small proportion to the Diameter of the Image” (AUL MS 2131/6/I/23, 2v, in Reid 1997, p. 332). The range of distinct vision, within which accommodation of the crystalline lens occurs, is between six or seven inches and fifteen or sixteen feet: see Reid 1997, VI.22: 180/5–10. Reid based his views on distinct vision on “An Essay on Distinct Vision” by James Jurin, appended to Robert Smith’s treatise on optics: see Smith (1738), Vol. 2, p. 136ff.

In Chapter 6, Sections 11 and 12, of Reid (1997), introduces this law in the context of his explanation of our seeing objects erect by means of inverted images on the retina.

See Reid (1997), VI.12: 127–130.

In this regard, Yaffe (2002), pp. 604–606, claims that Reid’s argument for the geometry of visibles depends on the identification of the eye with a point in space. According to Yaffe, the justification for this association of the eye with one point in space arises from “the need to limit our discussion to objects that are in focus” (ibid., p. 604).

See Porterfield (1737), pp. 250–254; Porterfield (1759), Vol. II, pp. 310–314. In the case of double vision, “the mind mistakes the situation of the eye, and supposes that is directed to the same object with the other” (Porterfield 1759, Vol. II, p. 312). Reid follows this explanation in his Aberdeen lectures from 1757–58, AUL MS K160, p. 300ff.

The memory of the original location of points of the retina appears to be an instance of innate knowledge that cannot be modified by experience.

This familiar measure of distance may also amount to a precise standard of measure (such as a metre, a foot, or an inch.). However, the precision of a standard is not necessary in order for us to say that we have an undetermined notion of the distance of some objects by comparison with other objects whose distance is familiar to us by our everyday experience.

Weldon is not familiar with the work of Fearn, and so presents this simply as a possible objection to Reid.

At one point, Reid gave the following explanation: “Hence we see the reason that a line, which is straight to the eye, may return into itself: for its being straight to the eye, implies only straightness in one dimension; and a line which is straight in one dimension may notwithstanding be curve in another dimension, and so may return into itself” (Reid 1997, VI.9: 107/28–32). This remark by itself is not sufficient to explain why all visible straight lines appear or can be imagined to appear, if we imagine them prolonged, to return into themselves. Indeed, it is not true that all visible right lines, that is, lines that are straight in the dimension of left and right (or up and down), are also curved in the dimension of backward and forward and so it is not true that all visible right lines do actually return in themselves. Daniels seems to imply that a visible right line will appear to return on itself for the following reason: if the eye is fixed in one point and capable of 360 degree rotation on its centre, it will trace the path of a line AB beyond one extremity, by rotating on its centre, until it finally sees it reappear (see Daniels 1989, p. 6). However, independently of whether the eye is actually capable of rotation (or of translation), the reason why a visible right line appears or can be imagined to appear to return into itself was expressly stated by Reid in his first three principles of the geometry of visibles, and is a necessary consequence of considering the eye as capable of perceiving only the position of objects with regard to the eye (see Reid 1997, VI.9: 103/15–104/5).

A similar point about the sphere as unique surface of projection is made by Belot (2003).

I have in mind some of the objections raised by Falkenstein (2015, forthcoming) in a draft of the article submitted for this issue of Topoi. Falkenstein himself suggests ways to answer these objections.

See Reid (1997), V.6: 65–67. With regard to the possibility of 360 degree vision, Falkenstein (2015, forthcoming) also argues that a person able to see in all directions at once at a given moment should experience the horizon as a closed curve (and not as a line proceeding in directum as Reid says).

I rely for my account of this distinction on Long (2006), pp. 5–9.

Long (2006), p. 7, refers to Aquinas, Summa Theologiae I.85. 1 ad 1. Long also gives references to Aristotle’s theory of abstraction (ibid., pp. 5–6).

The method adopted by Reid is similar to the analysis ex ante used in economics. This type of analysis has also been subject to the same kind of criticism levied against Reid’s experiments, since it would disregard the actual complexities of the real world. But it is only by disregarding, for the time being, actual complexities that one can isolate mechanisms such as laws of supply and demand that do certainly play a role in price formation: see Long (2006).

Reid introduced the Idomenians as part of the travel report of a fictional Rosicrucian philosopher in his first discourse to the Aberdeen Philosophical Society, dated 14 June 1758, in order to illustrate the two-dimensional geometry of visibles that a being endowed only with sight would have (see Reid 1997, p. 273). In this discourse, Reid identified the fictional Rosicrucian philosopher as “Joannes Rudolphus Apodemus,” while in the later Inquiry, published in 1764, he called him “Johannes Rudolphus Anepigraphus.” “Johannes” and “Rudolphus” are names consecrated by the Rosicrucian tradition: “Johannes” brings to mind Johannes Valentinus Andreae (1586–1654), the alleged author of one of the foundational documents of Rosicrucianism, The Chemical Wedding of Christian Rosencreutz (1616). Rudolphus brings to mind the emperor Rudolphus II (1552–1612), a well-known figure in the history of the Hermetism. “Apodemus” means “on travel” or “abroad.” “Anepigraphus” might be taken to stand for “anonymous,” although its most common use is for artifacts without inscription or legend, or manuscripts without title. Some bibliographic repertoires in Latin apply the term “anonymus” to indicate that the author is unknown and the term “anepigraphus” to indicate that the work does not bear any title. In the Inquiry, Reid facetiously suggests that Anepigraphus might be the same ancient Greek alchemist writer that “Borrichius, Fabricius, and others” refer to, although he acknowledges that he does pretend to determine the question conclusively (Reid 1997, VI.9: 111/25–30). Indeed, the early modern authors Reid mentions refer to such Anepigraphos Philosophos or simply Anepigraphos. Olaus Borrichius (latinized name of Ole Borch, 1626–1690)—a Danish scientist, physician, grammarian and poet—lists Anepigraphus as one of the ancient Greek alchemists in manuscripts kept by various libraries in Europe: see Borrichius (1668), p. 97 and p. 100; and (1674), p. 78, and p. 80. In his edition of Reid’s Inquiry, D.R. Brookes notes that Borrichius is mentioned by William Briggs in his Nova Visionis Theoria, a text Reid criticizes in the Inquiry (see Reid 1997, p. 228). Fabricius is Johann Albert Fabricius (1668–1736), a German classical scholar and bibliographer. He mentions Anepigraphus in Fabricius (1724), pp. 765–766, and p. 776. It appears that by the time Reid wrote about the Idomenians, the term “Rosicrucian” had already acquired a disparaging connotation in certain philosophical circles. In the Essay concerning Human Understanding, Locke accused Descartes of being “a step beyond the Rosecrucians” in order to ridicule the Cartesian doctrine that the soul always thinks, even while we do not dream (Locke 1975, II.i.19). In a footnote to his main work, the Scottish philosopher Andrew Baxter (1686 ca.–1750) makes some reference to Rosicrucianism in an objection to his own theory of dreams. According to the imaginary critic in this footnote, Baxter’s theory makes dreams “mere enchantment and Rosicrucian-work, which it is absurd to admit into philosophy and among natural appearances” (Baxter 1733, p. 288). The Scottish poet Allan Ramsay (1686–1758) makes a few comic references to Rosicrucians in his poems. In a footnote he adds some explanation: “Rosicrucians. A people deeply learn’d in the occult sciences, who conversed with aerial beings. Gentlemanlike kind of necromancers, or so” (Ramsay, 1751, vol. 1, p. 121, from the “Familiar Epistles,” Epistle II). Although playful references to Rosicrucianism abound in the eighteenth-century literature, it appears that many took it seriously (McIntosh 1992). Indeed, Rosicrucianism played a large role in the rise of secret societies in the eighteenth century, and we should see this renewed popularity as further evidence for the continuity between the Renaissance and the Age of Enlightenment (Yates 1972; Fleming 2013). There are still many questions left unanswered about Reid’s references to the Rosicrucianism. In particular, it is not clear what immediate sources of knowledge of Rosicrucianism were available to Reid and why he chose the name “Idomenians.” Beside the reference to the Rosicrucian philosopher Apodemus/Anepigraphus in the discourse from 1758 and in the Inquiry, Reid mentions Rosicrucians in his manuscript notes from 1786 on Daniel Morhof’s Polyhistor, a universal bibliographic repertoire. Reid jotted down the titles of some Rosicrucian works mentioned in Book 1, Chapter 13 of the Polyhistor (see Morhof 1747, pp. 121–135): “13 De Collegiis Secretis Michaeli Maieri Tractatus Apologeticus pro Fratribus Rosae Crucis. Ottonii Heurnii Antiquitates Philosophiae Barbaricae. Petrii Mormii Arcana totius Naturae Secretissima!” (AUL MS 2131/3/II/1, 2r). These brief references might not be very significant since Reid took note of works on all and sundry subjects following the order of the Polyhistor. Book 1, Chapter 11 (“de libris Physicis secretioribus, praecipue Chemicis,” in Morhof 1747, pp. 110–111), of the Polyhistor takes notes also of ancient manuscripts on alchemy, including those whose authors were anonymous, but Reid fails to make any explicit connection with Anepigraphus. He says in commenting this chapter: “A great deal is here said of about ancient Greek Mss on Chymistry which though mostly suspected to be spurious, the Author thinks may contain usefull Secrets which deserve Attention” (AUL MS 2131/3/II/1, 1v).

See Yates (1972), p. 118ff. As Yates explains, the expression lusus serius and jocus severus were used by the Rosicrucian Michael Maier (1568–1622), one of the authors Reid refers to in his 1786 notes on the Polyhistor (see above note 28). One of the foundational documents of Rosicrucianism, The Chemical Wedding of Christian Rosencreutz (1616) was described by its alleged author, Johann Valentin Andreae as a “ludibrium, a fiction, or a jest of little worth” (Yates 1972, p. 43). The method of presenting of an important truth under the guise of a playful allegory was the stock-in-trade of Rosicrucians. Thus, Reid’s methodology in the tale of the Idomenians is Rosicrucian.

An early version of this paper has been presented at the conference “The Geometry of the Visual Field: Early Modern and Contemporary Approaches” in Fribourg, Switzerland. I would like to thank the participants to the conference, and in particular the organizer, Hannes Ole Matthiessen. I would also like to thank Lorne Falkenstein and two anonymous referees for their comments. Excerpts from Reid’s manuscripts are printed with kind permission of Aberdeen University Library.

References

AUL Aberdeen University Library Manuscripts

Baxter A (1733) An enquiry into the nature of the human soul: wherein the immateriality of the soul is evinced from the principles of reason and philosophy. Bettenham, London

Belot G (2003) Remarks on the geometry of visibles. Philos Q 53:581–586

Berkeley G (1975) Philosophical works including the works on vision. Dent, London

Borrichius O [Borch O] (1674) Hermetis, Ægiptiorum, et chemicorum sapientia ab Hermanni Conringii animadversionibus vindicata. Sumptibus Petri Hauboldi, Hafniæ [Copenhagen]

Borrichius O [Borch O] (1678) De ortu et progressu chemiæ dissertatio. Typis Matthiae Godicchenii, sumptibus Petri Hauboldi, Hafniæ [Copenhagen]

Daniels N (1972) Thomas Reid’s discovery of a non-Euclidean geometry. Philos Sci 3:219–234

Daniels N (1989) Thomas Reid’s inquiry: the geometry of visibles and the case for realism, 2nd edn. Stanford University Press, Stanford

Fabricius JA (1724) Bibliothecæ graecæ, volumen duodecim, etc. Sumtu Theodori Christophori Felgineri, Hamburg

Falkenstein L (2000) Reid’s critique of Berkeley’s position on the inverted image. Reid Stud 4:35–51

Falkenstein L (2015, forthcoming) Reid's account of the “Geometry of Visibles”: some lessons from Helmholtz. Topoi-Int Rev Philos

Fearn J (1830) A rationale of the laws of cerebral vision: comprising the laws of single and erect vision, deduced upon the principles of dioptrics. Longman et al, London

Fleming JV (2013) The dark side of the Enlightenment: wizards, alchemists, and spiritual seekers in the age of reason. Norton, New York

Grandi GB (2005) Thomas Reid’s geometry of visibles and the parallel postulate. Stud Hist Philos Sci 36:79–103

Grandi GB (2006) Reid’s direct realism about vision. Hist Philos Q 23:225–241

Hagar A (2002) Thomas Reid and non-Euclidean geometry. Reid Stud 5:52–63

Locke J (1975) Essay concerning human understanding. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Long RT (2006) Realism and abstraction on economics: Aristotle and Mises versus Friedman. Q J Aust Econ 9:3–23

Matthiessen HO (2015) Empirical conditions for a Reidian geometry of visibles. Topoi-Int Rev Philos. doi:10.1007/s11245-015-9318-3

McIntosh C (1992) The rose cross and the age of reason: eighteenth-century Rosicrucianism in central Europe and its relationship to the Enlightenment. Suny Press, Albany

Meadows PJ (2011) Contemporary arguments for a geometry of visual experience. Eur J Philos 19:408–430

Morgan M (1977) Molyneux’s question: vision, touch and the philosophy of perception. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Morhof DG (1747) Polyhistor literarius, philosophicus et practicus, etc, 4th edn. Sumptis Petrii Boeckmanni, Lubeck

Nichols R (2002) Visible figure and Reid’s theory of visual perception. Hume Stud 28:49–82

Nichols R (2007) Thomas Reid’s theory of perception. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Pastore N (1971) Selective history of theories of visual perception. Oxford University Press, New York

Porterfield W (1737) An essay concerning the motions of our eyes. Part I. Of their external motions. Medical Essays and Observations Revised and Published by a Society in Edinburgh 2nd ed. 3:160–263

Porterfield W (1759) A treatise on the eye, the manner and phænomena of vision, 2 vols. Millar London; Hamilton and Balfour, Edinburgh

Ramsay A (1751) Poems by Allan Ramsay, vols 2. Millar and Johnston, London

Reid T [1764] (1997) An inquiry into the human mind on the principles of common sense. Pennsylvania State University Press, University Park [references by chapter, section, page, line number]

Reid T [1785] (2002) Essays on the intellectual powers of man. Pennsylvania State University Press, University Park [references by essay, chapter, page, line number]

Scheiner C (1619) Oculus: hoc est, fundamentum opticum [etc.]. Agricola, Oenipons [Innsbruck]

Smith R (1738) A compleat system of opticks in four books, viz. a popular, a mathematical, a mechanical, and a philosophical treatise. To which are added remarks upon the whole. Crownfield, Cambridge; Austen and Dodsley, London

Van Cleve J (2002) Thomas Reid’s geometry of visibles. Philos Rev 111:373–416

Weldon S (1978) Thomas Reid’s theory of vision. Dissertation, McGill University

Weldon S (1982) Direct realism and visual distortion: a development of arguments from Thomas Reid. J Hist Philos 20:355–368

Yaffe G (2002) Reconsidering Reid’s geometry of visibles. Philos Q 52:602–620

Yates F (1972) The Rosicrucian Enlightenment. Routledge, London and New York

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Grandi, G.B. Distance and Direction in Reid’s Theory of Vision. Topoi 35, 465–478 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11245-015-9332-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11245-015-9332-5