Abstract

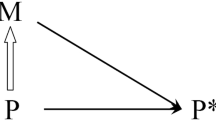

In this paper I develop a novel response to the exclusion problem. I argue that the nature of the events in the causally complete physical domain raises the “problem of many causes”: there will typically be countless simultaneous low-level physical events in that domain that are causally sufficient for any given high-level physical event (like a window breaking or an arm raising). This shows that even reductive physicalists must admit that the version of the exclusion principle used to pose the exclusion problem against non-reductive physicalism is too strong. The burden is on proponents of the exclusion problem to provide a reason to think that any qualifications placed on the exclusion principle will solve the problem of many causes while ruling out causation by irreducible mental events.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For a defense of the exclusion problem, see Kim 1993, 2003. I assume that an event is an object instantiating a property at a time. If one adopted a different view of events, then the terms of the debate change but not its substance. E.g., if one adopted a Davidsonian view of events and thought of causation as an extensional relation over them, then the exclusion problem shifts to a debate about what Terence Horgan (1989) has called “quausation.”

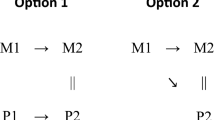

There may not be much difference between these responses in the end. They merely disagree on how best to understand overdetermination. The former adopts a narrow reading of ‘overdetermination,’ according to which two simultaneous events, A and B, overdetermine a given event only if A and B are (metaphysically or nomologically) independent. The latter interprets ‘overdetermination’ broadly, so that any two numerically distinct simultaneous sufficient causes of a given event overdetermine that event.

A micro-based property is the property of having proper parts propertied and related in certain ways. I will say that an event is micro-based if its constituent property is a micro-based property.

However, Sturgeon (1998) has claimed that it is not part of science or commonsense that mental events have low-level physical effects. In effect, Sturgeon claims that the plausibility of completeness and of the causal efficacy of the mental trade on distinct senses of ‘physical.’ I will set aside this kind of objection to the exclusion problem here, since others have addressed it (e.g. Witmer 2000). That is, I will grant the proponents of the exclusion problem the strong claim that the low-level physical domain contains a sufficient cause for every inclusive physical event.

Note that Kim’s reasoning need not automatically lead to the collapse of the distinction between high-level and low-level physical domains, for high-level physical properties plausibly include more than just micro-based properties of aggregate objects. Further, it is somewhat misleading to continue to use the term “low-level”, since the “low-level” physical domain includes molecules, cells, organisms, etc. and their micro-based properties. However, as Kim notes, in Oppenheim and Putnam’s scheme, “the only levels scheme that has been worked out with some precision … the bottom level of elementary particles … is in effect the universal domain that includes molecules, organisms, and the rest” (2003, p. 173 n. 23).

Here Kim seems to assume that baseballs and other macro-objects are identical to aggregates of microscopic entities. In this paper, I do not make this stronger assumption, as it is arguably not needed to generate the exclusion problem.

An anonymous referee wondered why the micro-based neurophysiological property involved in C counts as low-level physical. There are likely to be difficult issues involved in developing a coherent, general metaphysical account of levels, and I offer no such account here. I am merely following Kim’s assumption that the low-level physical domain must be closed under the formation of micro-based properties if completeness is to be true of the low-level physical domain. I drop that assumption in Sect. 4.

What about other approaches to the problem of the many? Clearly, nihilism about sufficient causes is not an option for the defenders of the exclusion problem nor is claiming that constitution is not identity. One might try the relative identity approach and claim that although C and C’ are not the same low-level physical event, they are the same sufficient cause. In addition to the standard objections to relative identity, this approach cannot simply say that C and C’ are the same sufficient cause, for in some contexts their differences are causally relevant. Rather, it must say that they are the same sufficient cause of E, and thus make identity relative to very narrowly construed, ad hoc “sortals.” Partial identity is not a plausible option either. While it may be that we count by “almost identity” when we talk about everyday things like cats and clouds, it is ad hoc to claim that we do so when talking about low-level physical causes. This is related to a key difference between the problem of the many and the problem that faces the defender of the exclusion problem. In the former we are trying to defend a commonsense belief, in the latter a theoretical view to which the defender of the exclusion problem is driven.

Note that Kim (2003, p. 158) sets up the exclusion problem in terms of “choosing” the physical cause over the mental one. He does so for good reason. The reductionist is trying to argue that non-reductive physicalism is inconsistent. So he must assume for the sake of argument that there are two simultaneous sufficient causes, one physical and one mental and attempt to show that this leads to a conflict with completeness and the exclusion principle, giving us reason to conclude that the mental event is not a cause (unless it just is the physical event under another name). Thanks to Brian Weatherson for discussion of this point.

Thanks to Andy Egan for suggesting this response.

Filling in the details of this claim overlaps with the non-reductive physicalist project of spelling out the relation between mental and physical events. For example, is it determination, realization, or some other asymmetric determination relation? However, if the arguments in this paper are correct, then doing so is not necessary to show where the exclusion problem goes wrong as an attack on non-reductive physicalism.

There are reasons to doubt whether plural quantification is ontologically innocent—i.e. whether it commits one to any entities in addition to the individuals quantified over in first-order logic (see, e.g., Resnik 1988). For broadly scientific reasons to reject nihilism about composite objects, see Early 2006. I set these aside for the sake of argument.

Of course, this is not Merricks’ view, for he rejects the completeness of physics (2001, pp. 140ff.).

Karen Bennett has also recently argued that Unger’s original problem of the many faces the compositional nihilist as well as the believer in composite objects. According to Bennett: “Where the believer has many mostly overlapping objects of the same kind, the nihilist has many mostly overlapping instantiations of the same property” (2009, p. 67). Thanks to an anonymous referee for directing me to this discussion.

References

Baker, L. R. (1993). Metaphysics and mental causation. In J. Heil & A. Mele (Eds.), Mental causation (pp. 75–95). New York: Clarendon.

Bennett, K. (2003). Why the exclusion problem seems intractable, and how, just maybe, to tract it. Noûs, 37, 471–497.

Bennett, K. (2008). Exclusion again. In J. Hohwy & J. Kallestrup (Eds.), Being reduced (pp. 280–305). Oxford: Oxford UP.

Bennett, K. (2009). Composition, colocation, and metaontology. In D. Chalmers, D. Manley, & R. Wasserman (Eds.), Metametaphysics (pp. 38–76). New York: Clarendon.

Chalmers, D. (1996). The conscious mind. New York: Oxford.

Early, J. (2006). Chemical “substances” that are not “chemical substances”. Philosophy of Science, 73, 841–852.

Feigl, H. (1958). The ‘mental’ and the ‘physical’. In H. Feigl, M. Scriven, & G. Maxwell (Eds.), Minnesota studies in the philosophy of science, vol. 2 (pp. 370–497). Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Funkhouser, E. (2006). The determinable-determinate relation. Nous, 40, 548–569.

Haug, M. (2009). Two kinds of completeness and the uses (and abuses) of exclusion principles. Southern Journal of Philosophy, 47, 379–401.

Horgan, T. (1989). Mental quausation. Philosophical Perspectives, 3, 47–76.

Horgan, T. (1997). Kim on mental causation and causal exclusion. Philosophical Perspectives, 11, 165–184.

Hossack, K. (2000). Plurals and complexes. British Journal for the Philosophy of Science, 51, 411–443.

Kim, J. (1993). Mechanism, purpose and explanatory exclusion. In his Supervenience and Mind. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, pp. 237–264.

Kim, J. (1998). Mind in a physical world. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press.

Kim, J. (2003). Blocking causal drainage and other maintenance chores with mental causation. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 67, 151–176.

Merricks, T. (2001). Objects and persons. Oxford: Oxford UP.

Noordhof, P. (1999). Micro-based properties and the supervenience argument. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, 99, 109–114.

Papineau, D. (2001). The rise of physicalism. In C. Gillett & B. Loewer (Eds.), Physicalism and its discontents (pp. 3–36). Cambridge: Cambridge UP.

Resnik, M. (1988). Second-order logic still wild. Journal of Philosophy, 85, 75–87.

Schaffer, J. (2003). Over determining causes. Philosophical Studies, 114, 23–45.

Sider, T. (2003). What’s so bad about overdetermination? Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 67, 719–726.

Sturgeon, S. (1998). Physicalism and overdetermination. Mind, 107, 411–432.

Unger, P. (1980). The problem of the many. Midwest Studies in Philosophy, 5, 411–467.

Witmer, D. G. (2000). Locating the overdetermination problem. British Journal for the Philosophy of Science, 51, 273–286.

Yablo, S. (1992). Mental causation. Philosophical Review, 101, 245–280.

Acknowledgments

Some of the ideas in this paper descend from an unpublished essay titled “A Novel Solution to the Exclusion Problem,” which I presented at the 2004 meeting of the Creighton Club in Skaneateles, NY. Thanks to the audience on that occasion and especially to my commentator, Gregory Fowler, for helpful questions and comments. I am also grateful to Richard N. Boyd, Sydney Shoemaker, Nicholas Sturgeon, and two anonymous referees for discussion about, or comments on, previous versions of this paper. Some of this material is based upon work supported under a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship. Additional funding was provided by a Faculty Summer Research Grant from The College of William and Mary. I thank both institutions for their support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Haug, M.C. The Exclusion Problem Meets the Problem of Many Causes. Erkenn 73, 55–65 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10670-010-9211-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10670-010-9211-9