Abstract

Theories of well-being are typically divided into subjective and objective. Subjective theories are those which make facts about a person’s welfare depend on facts about her actual or hypothetical mental states. I am interested in what motivates this approach to the theory of welfare. The contemporary view is that subjectivism is devoted to honoring the evaluative perspective of the individual, but this is both a misleading account of the motivations behind subjectivism, and a vision that dooms subjective theories to failure. I suggest that we need to revisit and reinstate certain features of traditional hedonism, in particular the idea that felt experience plays a role that no theory of welfare can afford to ignore. I then offer a sketch of a theory that is subjective in my preferred sense and avoids the worst sins of hedonism as well as the problems generated by the contemporary constraints of subjective theorists.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For example, Griffin (1986, p. 33).

Sumner (1996, Chap. 2).

Some theorists have argued that the notion of full information is incoherent—that there is no answer to the question what an individual would want with full information. See e.g. Rosati (1995). Here, for the purpose of argument, I assume such views are coherent, but argue that even so we have no guarantee that with full information Savita will see her situation as being as bad as it is.

On this point I disagree with theorists like Fred Feldman who defend an attitudinal account of pleasure. See Feldman (2004).

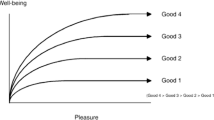

This part of SKETCH leaves room for handling concerns about pure mental state theories. Those who reject what has come to be known as “the experience requirement”—i.e. those who believe it is not important that someone know her life is going well, but only that it actually be going well—can interpret the theory so that the ranking of lives above the affect line is done in terms of how well a particular life actually fulfills her evaluative preferences. However, my theory places limits on this. Since affect is dominant up to a point, SKETCH would not endorse the idea that a life in which (a) things are actually going well according to one’s preferred scheme of values, but (b) one doesn’t know this, and so (c) one is miserable, is a good life.

References

Brink, D. O. (1989). Moral realism and the foundations of ethics. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Feldman, F. (2004). Pleasure and the good life: On the nature, varieties, and plausibility of hedonism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Feldman, F. (2010). What is this thing called happiness? Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Griffin, J. (1986). Well-being: Its meaning, measurement, and moral importance. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hawkins, J. (2008). Well-being, autonomy, and the horizon problem. Utilitas, 20, 143–168.

Rosati, C. (1995). Persons, perspectives, and full information accounts of the good. Ethics, 105, 296–325.

Sumner, L. W. (1996). Welfare, happiness, and ethics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hawkins, J.S. The subjective intuition. Philos Stud 148, 61–68 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-010-9505-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-010-9505-4