Abstract

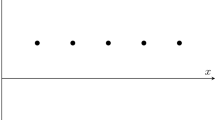

Causal realists maintain that the causal relation consists in “something more” than its relata. Specifying this relation in nonreductive terms is however notoriously difficult. Michael Tooley has advanced a plausible account avoiding some of the relation’s most obvious difficulties, particularly where these concern the notion of a cross-temporal “connection.” His account distinguishes discrete from nondiscrete causation, where the latter is suitable to the continuity of cross-temporal causation. I argue, however, that such accounts face conceptual difficulties dating from Zeno’s time. A Bergsonian resolution of these difficulties appears to entail that, for the causal realist, there can be no indirect causal relations of the sort envisioned by Tooley. A consequence of this discussion is that the causal realist must conceive all causal relations as ultimately direct.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

See, for example, Armstrong’s account. D.M. Armstrong, A World of States of Affairs (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1997), 74.

The term ‘nondiscrete’ is Tooley’s. See Michael Tooley, “The Nature of Causation: A Singularist Approach” (Canadian Journal of Philosophy Supplementary Vol. 16, 1990), 296.

Tooley, for example, is explicit in representing direct and ‘nondiscrete’ causation as species of a generic causality. Tooley, ibid, 294f.

Jonathan Bennett, Events and Their Names (Indianapolis: Hackett, 1988), 46.

Jonathan Bennett, ibid, 44.

David K. Lewis, “Causation” in his Philosophical Papers vol. II (New York: Oxford University Press, 1986), 167. Lewis’ emphasis and ellipsis.

Another significant difference concerns the theorists’ judgment on the question of causal realism. Lewis, of course, is an avowed antirealist where causation is concerned. That is, he endorses the thesis of ‘Humean supervenience.’ Lewis, ibid, xii. Bennett, on the other hand, is unwilling to take a stand on the issue. Bennett, op. cit., 52.

Dean Zimmerman, “Immanent Causation,” Philosophical Perspectives 11 (1997), 447.

Dean Zimmerman, ibid, 448. The ‘essential parts’ of events are not necessarily their proper parts, on Zimmerman’s view. Indeed, it would appear that in cases such as this part and whole are identical.

Other philosophers appear to be similarly unconcerned about the difficulty of causation in a dense series. Lange, for example, writes that

within any interval prior to t = 3, no matter how short, there is a complete set of causes of the body’s moving at 5 m/s at t = 3. For example, within the interval between t = 2.9 and t = 3, there is the body’s moving at 5 m/s at t = 2.99 and its feeling no forces between t = 2.99 and t = 3 inclusive. Within the narrower interval between t = 2.999 and t = 3, there is another complete set of causes: the body’s moving at 5 m/s at t = 2.9999 and its feeling no forces between t = 2.9999 and t = 3 inclusive. There is a complete set of causes arbitrarily near in space and time to the effect. See Marc Lange, An Introduction to the Philosophy of Physics (Malden: Blackwell Publishing Company, 2002), 11. Lange’s emphasis.

Lange, here, represents various stages in the existence of a body moving at 5 m/s as having the causal power to bring about or sustain that motion at later times. The body at t = 2.9 constitutes a sufficient cause for the motion of that body at t = 3. In answer to the question how this might be so without postulating action at a temporal distance, Lange simply decreases the distance in question to one arbitrarily small. “A cause,” he maintains, “cannot have an influence at some distant location without having effects at all of the locations in between.” (Lange, ibid, 6.) Thus, if the body at t = 2.9 causes its motion at t = 3, then for every moment in the interval between those times there is a stage caused by the body at t = 2.9 and causing the motion of the body at t = 3. This results in there being “no ‘gap’ between cause and effect.”The trouble with this formulation, however, lies in explaining how the gap comes to be filled. Given that the body is moving at t = 2.9, how does it come to pass that it is moving (or exists, for that matter) at t = 3, or 2.9999, or 2.999, or 2.99? Lange’s approach rests on the assumption that there is indeed a causal relation between the body at t = 2.9 and that at t = 3; and in that context, it makes sense to postulate the existence of causal intermediaries. However, this assumption begs the question whether the cross-temporal causal relation is in the first place intelligible. Like Zimmerman, we wish to say, perhaps, that the action of one stage ‘passes through’ others on its way to another. However, as already noted, this formulation cannot be said to represent understanding.

Zimmerman seems to mistake this question for the question whether one member may have more than one cause and more than one effect. After first noting the ‘skipping’ problem, he addresses an argument by Russell intended to show that cause and effect must be spatiotemporally contiguous. He rejects this conclusion, however, on the ground that it rules out a thing having more than one cause or more than one effect. However, Russell’s argument clearly is intended to apply only to direct causal relations: the question is how to understand indirect causal relations without construing them in terms of direct causation. See Bertrand Russell, Mysticism and Logic (London: Longman’s Green, and Col, 1929), 181–185.

Tooley, op. cit., 298.

Tooley, ibid, 299.

Tooley, ibid, 297.

Tooley, ibid.

Whether we should understand a spatial expanse as a relation is a further problem of interpretation here. The ambiguity of the status of a connection as a relation or an object is due perhaps to Tooley’s understanding of universals. Like Armstrong, he conceives instances of universals to be ontologically basic. Instances of relations will consequently be basic entities, for Tooley, however they may be arranged across spacetime. I believe that this represents a confusion with the concept of object, which I take to refer only to entities arranged across space but not time.

Henri Bergson, “The Cinematographic View of Becoming,” in Wesley Salmon, ed., Zeno’s Paradoxes (Indianopolis: Hackett, 2001), 63–64. Bergson’s emphasis.

Such a distinction can be made only ‘in conception’, maintains Descartes. “[A] conceptual distinction is a distinction between a substance and some attribute of that substance without which the substance is unintelligible; alternatively, it is a distinction between two such attributes of a single substance. Such a distinction is recognized by our inability to form a clear and distinct idea of the substance if we exclude from it the attribute in question, or, alternatively, by our inability to perceive clearly the idea of one of the two attributes if we separate it from the other. For example, as a substance cannot cease to endure without also ceasing to be, the distinction between the substance and its duration is merely a conceptual one.” (Rene Descartes, Principles of Philosophy, I.62.) If the arrow is our substance, then it being a substance – i.e., an existent substance located in physical reality – cannot be thought coherently independently of its continuing to exist. I believe that we must agree with Descartes here that we are unable to form a clear and distinct idea of a physical substance existing for a durationless moment. Such an idea represents, at best, a limit to what we can clearly conceive – a claim seconded by Kant.

Tooley’s failure to recognize a Zenonian threat to his account of causation is perhaps ascribable to the weakness of his causal realist credentials. Causation, on his account, is a matter of the enhancement of the probability of the occurrence of an event (see Tooley, op. cit., 305–312). This bland notion gives little substance to the notion that one event brings about another. It may be true of causes that they increase the probability of their effects; but this does not by itself capture the force of causal realism, for the same may be held on a Humean account. To be sure, Tooley subscribes explicitly only to the doctrine of causal singularism. It seems plain, however, that the inspiration for that view is causal realism. Indeed, if it is not, ultimately, the reality of causal relations over and above their relata that distinguishes singularism from Humean views, then there is in fact no such distinction: causal singularism is, as I understand it, intended as an analysis of causal realism.

This account may raise concern regarding the reality of causal relations. If causal relations are so easily drawn, are we then to infer causality ultimately to be ideal? I do not, at present, have a clear opinion on this matter: I believe that causality may well be real; a positive account of it is the subject of continuing work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

About this article

Cite this article

Oakes, M.G. Can Indirect Causation be Real?. Int Ontology Metaphysics 8, 111–122 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12133-007-0010-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12133-007-0010-y