Abstract

Research on corporate philanthropy typically focuses on organization-external pressures and aggregated donation behavior. Hence, our understanding of the organization-internal structures that determine whether a given organization will respond philanthropically to a specific human need remains underdeveloped. We explicate an attention-based framework in which specific dimensions of organization-level attention focus interact to predict philanthropic responses to an emergent human need. Exploring the response of Fortune Global 500 firms to the 2004 South Asian tsunami, we find that management attention focused on people inside the organization (employees) interacts with both attention for places (countries in the tsunami-stricken region) and attention for practices (corporate philanthropy in general) to predict the likelihood of charitable donations. Our research thus extends beyond the prevailing institutional perspective by highlighting the role of attention focus in corporate responsiveness to emergent societal issues.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Organizational social behaviors like corporate philanthropy continue to garner considerable interest among organizational researchers. Extant research typically explains corporate philanthropy as a function of societal expectations (Adams and Hardwick 1998; Brammer and Millington 2004; Crampton and Patten 2008; Galaskiewicz and Burt 1991; Marquis et al. 2007) or in terms of reputation and financial management strategies (Brammer and Millington 2005; Lev et al. 2010; Saiia et al. 2003; Su and He 2010). Most research emphasizes structural institutional factors that explain variance in firms’ overall levels of annual giving. While generating valuable insights, such studies reveal little about the circumstances under which a specific organization opts to donate to a specific cause. In order to generate a more fine-grained understanding of the drivers of corporate philanthropy, however, scholars have begun to call for research into the organization-internal mechanisms that explain when a given organization will donate to a given cause (Crampton and Patten 2008; Dunfee 2006).

Corporate philanthropy is an allocation of organizational resources aimed at alleviating human needs in society, such as poor health care, illiteracy, economic underdevelopment, or environmental pollution (Atienza and Renz 2006). Statistics show that corporate philanthropy is on the rise (Foundation Center 2009), even though human needs are not issues that typically lie within the realm of most business organizations’ primary economic and fiduciary responsibilities. For any human need that comes to their attention, managers make specific decisions about whether or not to allocate resources—in the form of cash, goods, services, or time—to the alleviation of that need. Research shows that even in cases of human needs that grab our attention, such as the 2010 Haiti earthquake or Hurricane Katrina in 2005, some organizations respond charitably, while others do not (Fritz Institute 2005; IBLF 2005; Muller and Whiteman 2009). In this paper, we develop an identity-driven, attention-based framework to explain why. In so doing, we shed light on the role of organization-level attention focus in corporate philanthropy decisions in particular, and on the mechanisms and processes that underlie corporate responsiveness to societal issues more generally (Aguilera et al. 2007; Grant 2012).

Research shows that attention allocation drives organizational action, and that organizational identity is central to attention allocation (Barnett 2008; Dutton and Dukerich 1991; Kaplan 2008; Ocasio 1997, 2011). Thus, an identity-driven, attention-based perspective can help explain how patterns of organizational attention focus relate to the likelihood of organizational philanthropic action in response to a specific human need. Organizational attention focus refers to the elements of the organization and its environment that feature most prominently in the attention hierarchy of organization management (Davenport and Beck 2001; Nadkarni and Barr 2008). Patterns of attention focus vary in systematic ways across organizations and are relatively stable predictors of organizational action because they are rooted in organizational identity (Hoffman and Ocasio 2001). In this paper, we propose a framework in which management attention focused on people inside the organization (employees) interacts with attention focused on places (the geographic locations specific to the need in question) and practices (corporate philanthropy in general) to predict charitable responses to an emergent human need.

With respect to people, psychological research has established that attentiveness toward the needs of others inside the organization (i.e., one’s colleagues) is an organization-level manifestation of identity-driven, other-directed concern (Dutton et al. 2006; Grant et al. 2008; Madden et al. 2012). We argue that an attention focus directed at people inside the organization also plays a key role in the likelihood that an organization allocates resources toward the alleviation of human needs outside the organization, because organizational identity drives organizations to manage external relationships in the same way they manage their internal relationships (Brickson 2005; Rousseau and Wade‐Benzoni 1994). As employees form the central human element inside the organization, we expect that greater prominence of employees in the organizational attention hierarchy will be related to the likelihood of responding philanthropically to human needs that arise outside the organization.

With respect to places, sociological research has shown that organizations allocate the most resources to subsidiaries and units in the geographic locations that management pays the most attention to (Bouquet and Birkinshaw 2008). We extend this logic to include organization-external resource allocations such as corporate philanthropy. With respect to practices, in light of research showing that organizational routines are not always activated in the face of emergent issues (Bansal 2003; Kaplan 2008), we argue that attention for the practice of corporate philanthropy in general is an important but understudied mechanism driving charitable responses to specific emergent human needs. Finally, based on the notion that resource allocation decisions are driven in part by interactions among attention structures (Barreto and Patient 2013), we propose that attention for people interacts with attention for places and practices to affect the likelihood of corporate philanthropy.

Taking the response of Fortune Global 500 firms to the 2004 South Asian tsunami as our research setting, we conducted regression analysis using a lagged structure to explore how established organization-level attention for employees (people), tsunami-stricken countries (places), and corporate philanthropy (practices) interact to predict charitable responses to the tsunami disaster. As an attention-grabbing ‘watershed event’ in international corporate philanthropy (Urma 2005), the tsunami disaster forms a natural experiment for understanding the relationship between organizational attention focus and subsequent philanthropic action in response to an emergent human need. We find that evidence of greater management attention for tsunami-stricken countries and corporate philanthropy in companies’ 2003 annual reports both predict donation likelihood in response to the 2004 tsunami, and that both effects are positively moderated by attention to employees. Importantly, our findings show that these attention-based effects exist above and beyond institutional effects such as the scale of the organization’s operational presence in the geographic region (Bouquet and Birkinshaw 2008).

Our study on the relationship between attention focus and corporate philanthropy makes three main contributions to organizational research. First, our findings contribute to research on organizations in society by highlighting the role of attention focus as a driver of organizations’ responsiveness to societal issues. Second, we extend research on the ways organizations allocate resources through geographic space by showing how interactions between different attention foci affect when and where organizations allocate resources to corporate philanthropy. Third, we contribute to research on attention by highlighting the interplay between organization-internal and organization-external attention foci as a mechanism through which organizations manage internal and external relations in parallel. In the following sections, we explicate our theoretical arguments, outline our research methodology, present our results, and discuss our findings.

An Attention-Based Framework of Corporate Philanthropy

Much of the research explaining variance in corporate philanthropy typically focuses on structural, contextual factors that drive giving, such as the level of stakeholder pressure and societal expectations (Adams and Hardwick 1998; Brammer and Millington 2004). Despite being valuable, these research studies still reveal little about why any particular firm would give to any specific cause as opposed to others. In contrast, another stream of research emphasizes the role of the organization’s geographic proximity to the social need in question (Crampton and Patten 2008; Galaskiewicz 1997; Marquis et al. 2007; Tilscik and Marquis 2013), but does not explain why or under which circumstances organizations give to causes farther away from ‘home.’ In addition, extant research typically approaches corporate philanthropy at a high level of aggregation by exploring variance in overall annual donation amounts. Thus existing research offers limited insight into the mechanisms inside organizations that antecede specific instances of giving, leaving unanswered an intriguing question: What organization-internal mechanisms affect whether a given organization is more likely than others to respond to a given human need with charity?

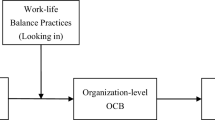

To address this question, we develop an identity-driven, attention-based framework (Fig. 1) to explain how established management attention for people, places, and practices, respectively, interact to predict the likelihood of future charitable action. The attention-based view departs from the premise that decision makers have limited capacities to attend to the full range of stimuli they face, and that organizations harbor structural features that shape the relative distribution of attention (Barreto and Patient 2013; Dutton et al. 2001; Ocasio 1997). If patterns of attention allocation determine when organizations allocate resources to address a given issue, then our framework is aimed at explaining how attention allocation activates some decisions and not others (Dutton et al. 2001). We explain this variance in decision activation in terms of organizations’ systematic variation in their attention focus (Barreto and Patient 2013; Nadkarni and Barr 2008); i.e., which elements of the organization and its environment figure most prominently in the organizational attention hierarchy (Davenport and Beck 2001). Because attention focus is rooted in organizational identity, attention focus varies systematically across organizations, and is relatively stable over time (Hoffman and Ocasio 2001). Although corporate philanthropy has thus far not been examined through an attention-based lens, we argue that attention focus offers insight into which features of the organization and its environment are considered important and relevant for the organization, and reveals important insights about where organizations direct their resources.

With respect to people, psychological research shows that attentiveness toward the needs of others inside the organization is a manifestation of other-directed concern rooted in organizational identity (Dutton et al. 2006; Grant et al. 2008). Given that identity drives organizations to manage internal and external relations in similar ways (Brickson 2005), we theorize that managerial attention directed at employees inside the organization may also be related to behaviors aimed at human issues outside the organization, such as corporate philanthropy. In regards to places, research using the attention-based view (Barnett 2008; Hoffman and Ocasio 2001; Rerup 2009) shows that the way in which organizational resources are allocated through geographic space can be explained by attention mechanisms (Bouquet and Birkinshaw 2008; Levy 2005). Building on attention-based research establishing that organizations direct the most resources toward subsidiaries and units in places to which management pays the most attention (Bouquet and Birkinshaw 2008), we theorize that the geographic focus of organizational attention may also affect socially directed resource allocations external to the organization, such as corporate philanthropy. With respect to practices, we propose that attention to practices is an important but understudied element of understanding the relationship between practices, as part of an organization’s potential ‘answer set’ (Ocasio 1997), and subsequent action. Specifically, although research on responsiveness to the needs of others emphasizes the importance of established practices in driving action (Dutton et al. 2006), other research notes that practices are not always engaged in the face of emergent issues for which such practices might be relevant (Bansal 2003; Kaplan 2008). We theorize that previously established attention for the practice of corporate philanthropy will predict subsequent philanthropic responses to an emergent human need, beyond the predictive effects of experience with the practice of corporate philanthropy itself. Finally, based on the notion that resource allocation decisions are driven in part through the way in which attention structures interact (Barreto and Patient 2013), we argue that attention for people amplifies the effects of attention for places and practices.

Employee Attention Focus: People in the Organizational Attention Hierarchy

Organizations vary systematically in their patterns of attention distribution. For instance, some organizations focus their attention primarily on customers, while others focus more on processes or innovation (Edvinsson and Sullivan 1996). Yet other organizations have a ‘human focus’ (Liebowitz and Suen 2000), in which employees, as the human element in organizations, are central to management attention patterns (Flamholtz et al. 2002; Lester et al. 2010). When managers pay more attention to employees, employees perceive management to be fair, just, and empathic (Cropanzano et al. 2007; Kellett et al. 2006), perceptions which lead to greater organizational identification and belonging (Bowen et al. 2000). Organizational identification and belonging in turn motivate employees to not only behave altruistically toward their colleagues inside the organization (Cohen-Charash and Spector 2001; Grant et al. 2008), but can also drive them to push for social behaviors directed outside the organization, including corporate philanthropy (Aguilera et al. 2007; Frey and Meier 2004).

Thus far, however, the link between attention and responsiveness to the needs of others has been explored primarily in terms of employees’ responsiveness to the needs of their colleagues (Lilius et al. 2011). In contrast, organization-level attention in relation to responsiveness to human needs outside the organization has rarely been considered (see Dutton and Dukerich [1991], for example). We argue that management attention focus has implications for employees’ attitudes toward social behaviors directed both inside and outside the organization. This is because identity drives organizations to manage relations with both internal and external actors according to similar principles, derived from the same set of organizational goals (Brickson 2005; Rousseau and Wade‐Benzoni 1994).

An employee attention focus, for example, is embedded in human-focused organizational identities, such as ‘normative’ (Foreman and Whetten 2002), ‘caring’ (Grant et al. 2008), or ‘collectivist’ identity orientations that emphasize ‘advancing broader welfare’ (Brickson 2005). Such organizational identities house core values such as ‘expressed humanity’ (Dutton et al. 2006) that ultimately shape organization-level responsiveness to the needs of others. While extant research has thus far only considered this human-focused responsiveness within the organization, some suggest that a human-focused organizational orientation may also drive responsiveness outside the organization as well because the organizational boundary is permeable to pain (e.g., Lilius et al. 2011; Muller et al. 2014). Thus, we argue that the relative amount of attention managers pay to people inside the organization (i.e., their employees) is related to the likelihood that management will allocate organizational resources to responsiveness toward an emergent human needs outside the organization. We hypothesize as follows:

Hypothesis 1

The more management focuses its attention on employees, the more likely the organization is to respond philanthropically to an emergent human need.

Geographic Attention Focus: Places in the Organizational Attention Hierarchy

Research has shown that geography matters for corporate philanthropy. For instance, corporate AQcontributions following the 2001 ‘9/11’ attacks, Hurricane Katrina, and the 2005 Kashmiri earthquake all involved significantly larger sums of money for organizations with a physical presence in the disaster-stricken region than for organizations without such a presence (Crampton and Patten 2008; Muller and Whiteman 2009). Yet organizations sometimes respond charitably to human needs in locations where they do not operate, and may not respond to human needs in the locations where they do. Thus ‘place embeddedness’ (Tilcsik and Marquis 2013) in the form of the structural pressures firms experience from the communities in which they operate, be it at home (Galaskiewicz 1997; Marquis et al. 2007; Useem 1988) or overseas (Brammer et al. 2009), is an incomplete explanation of corporate philanthropy. We extend beyond the embeddedness explanation to argue that corporate philanthropy, as a form of organization-external resource allocation, is subject to similar attention dynamics as are resources allocated within organizations.

Specifically, research has shown that organizations direct the most resources toward those units and subsidiaries to which they pay the most attention (Bouquet and Birkinshaw 2008). Thus, resource flows across geographic space are not only a function of an organization’s physical presence in a given location, but also of that location’s prominence in the organization’s attention hierarchy. Moreover, since geography not only distributes attention but is also an important element of an organization’s identity (Glynn and Abzug 2002; McKendrick et al. 2003; Romanelli and Khessina 2005), geographically defined attention patterns are likely to be relatively stable predictors of organizational resource allocation patterns (Bouquet and Birkinshaw 2008). In the context of our theorizing, we propose that the likelihood of philanthropic responses to emergent human needs in a particular geographic location is a function of the amount of attention an organization tends to pay to that location, and that these effects exist above and beyond the predictive effects of an organization’s physical presence in that location. Thus, geographic attention focus serves as an enabling mechanism that facilitates the channeling of organizational resources into corporate philanthropy in a specific location when a need in that location arises. This leads to the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2a

The more management focuses its attention on a particular geographic location, the more likely the organization is to respond philanthropically to an emergent human need in that location.

In addition, the attention-based view holds that organizational action is determined by patterns of attention directed both inside and outside the organization, and that the effects of one attention structure may be contingent upon the effects of other attention structures (Barreto and Patient 2013; Bouquet and Birkinshaw 2008; Ocasio 1997). Building on these arguments, we propose that internally directed attention (i.e., employee attention focus) interacts with externally directed attention (i.e., geographic attention focus) to predict corporate philanthropy. Specifically, whereas geographic attention makes human needs in a particular geography more salient (the ‘where’), employee attention focus gives that geographic attention focus purpose (the ‘why’). In combination, employee attention focus and geographic attention focus increase the likelihood the organization will aim resources at alleviating an emergent human need in a given geographic location, because those needs will be perceived to fit better with the organization’s set of issues and answers (Ocasio 1997). We hypothesize the following:

Hypothesis 2b

The more management focuses its attention on employees, the greater the effect of geographic attention focus on the likelihood of responding philanthropically to an emergent human need in a given geographic location.

Philanthropy Attention Focus: Practices in the Organizational Attention Hierarchy

Organizational identity also resides in organizational practices (Nag et al. 2007), and those established practices in part determine future behavior (Nelson and Winter 1982). As such, organizational responses to an emergent issue are a function not only of the issue itself, but also the available repertoire of responses (Dutton and Jackson 1987; Ocasio 1997). Prior experiences form the frame through which organizations interpret and act on issues, and the blueprint upon which they base their actions (Dutton et al. 1994). Specifically, past behavior with respect to certain issues legitimates organizational responses to similar issues in the future because that behavior becomes integrated in organizational identity, and identity shapes managerial interpretations of future issues (Bansal and Roth 2000; Bansal 2003; Dutton et al. 2006; Grant et al. 2008; Sharma 2000; Tilcsik and Marquis 2013).

At the same time, research shows that past behavior does not always beget future behavior (Bansal 2003; March and Shapira 1992). Practices which in hindsight are perceived as a misfit with the organization’s identity, and thus its issue and answer set, are less likely to be repeated (Bundy et al. 2013). Under such circumstances, management facing an emergent issue may fail to engage a relevant practice or even ignore it deliberately (Levinthal and March 1993; Nag et al. 2007). In line with research showing that practices themselves can also be a focus of organizational attention (Liebowitz and Suen 2000; Nadkarni and Barr 2008), we argue that how much attention management has paid to a particular practice in the past may be a more meaningful predictor of behavior than experience alone, because greater attention focus implies a greater degree of fit between the practice and organizational identity. When organizational attention is more directed toward a particular practice, management is more likely to actively consider that practice as a fitting potential response in the face of potentially relevant future issues (Hargadon and Fanelli 2002). Thus, we argue that management attention directed at the practice of corporate philanthropy predicts philanthropic responses to an emergent human need above and beyond the predictive effects of prior experience with that practice. This leads to the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3a

The more management focuses its attention on the practice of corporate philanthropy in general, the more likely the organization is to respond philanthropically to a specific emergent human need.

Extant research has also emphasized the importance of interactions between an organization’s focus of attention and experience with the routines or practices relevant for addressing an emergent issue. For instance, Kaplan (2008) reveals the amplifying role of experience in a particular domain on the relationship between management’s attention for that domain and subsequent investments in that domain. Similarly, Barreto and Patient (2013) show that domain-specific experience moderates the relationship between management’s interpretations of an emergent issue and the perceived capability to address that issue. Building on the previous hypothesis, we argue that considering the role of attention for domain-specific practices will contribute to a better understanding of the interactions between practices and attention in driving resource allocation decisions (Chattopadhyay et al. 2001; Dane 2013; Maula et al. 2013). Specifically, we expect that attention focus governing ‘how’ to respond to an issue interacts with attention focus related to the question of ‘why’ the organization should respond at all (Barreto and Patient 2013). This is because without sufficient attention for the ‘how,’ the ‘why’ may lack a clear focus of action, and without sufficient attention for the ‘why,’ attention for the ‘how’ lacks the motivational force to translate into action (Hargadon and Fanelli 2002; Rabinovich et al. 2009). Extending this logic, we argue that the effects of attention for the practice of corporate philanthropy (the ‘how’) are amplified by the motivating force of employee attention focus (the ‘why’) in driving organizational responsiveness to an emergent human need. Therefore, we hypothesize that

Hypothesis 3b

The more management focuses its attention on employees, the greater the effect of philanthropic attention focus on the likelihood of responding philanthropically to an emergent human need.

Methodology

In the present paper, we focus on the likelihood that a given firm would respond philanthropically to a given emergent human need. Hypothesizing on donation likelihood allows us to take a more fine-grained approach to understanding which firms donate to a given human need and which do not, in contrast to studies focused on variance in donation amounts of donors alone. Empirically, explaining variance in donation likelihood also helps us address some of the limitations of extant research. For instance, analyzing variance in (non-zero) donation values (Adams and Hardwick 1998; Brammer and Millington 2004) requires sampling on the dependent variable, creating a risk of sample selection bias (Heckman 1979). Other studies use Tobit censored or truncated regression models to accommodate zero-values along with continuous non-zero values (Brammer and Pavelin 2006; Petrovits 2006). The Tobit technique models a linear relationship through creation of a latent variable that construes pseudo-negative donation values. Yet Tobit models are only appropriate in situations where the latent variable can, in principle, take values below zero, which is not the case with corporate philanthropy. In addition, the Tobit model approach implicitly assumes that the decision to donate is a linear function of the same variables that predict donation amounts, in spite of recent research showing that the two decisions are better modeled independently (Wang et al. 2008; Wang and Qian 2011).Footnote 1

For our research setting, we take the response of the Fortune Global 500 to the 2004 South Asian tsunami. The tsunami disaster, caused by an earthquake off the coast of Banda Aceh, Indonesia, on the early morning of 26 December, 2004, was considered a watershed event that ‘raised corporate philanthropy to a new level’ (Urma 2005). With at least 226,000 dead or missing and 1.7 million displaced, the disaster triggered a magnanimous response from around the world. Companies contributed cash, goods, volunteers, and logistics more than doubling the previous high of $475 million raised in response to the September 2001 ‘9/11’ attacks. As such, the tsunami disaster forms an ideal natural experiment for understanding the relationship between organizational attention focus and subsequent philanthropic action in response to an attention-grabbing emergent human need.

Corporate Philanthropic Responses to the Tsunami

Our dependent measure is a binary outcome variable that indicates whether or not a given firm responded to the tsunami disaster with corporate philanthropy. We collected information on tsunami donations through corporate websites and press releases. We identified 351 firms that donated in response to the tsunami. To analyze our data, we used binomial logistic regression to model the likelihood that a given firm could be expected to donate. The binomial (maximum likelihood) logistic regression regresses a dichotomous outcome variable (in this case, donating firms versus non-donating firms) and can generate odds ratios for the outcome variable instead of coefficients alone (Hair et al. 1998; Hosmer and Lemeshow 2000). The odds ratio is expressed as

where Y is the dependent variable, equal to the chance that a firm would donate in response to the tsunami; and Z is a linear combination of independent variables or

The binomial regression thus provides information on which factors significantly affect the likelihood of a given firm to donate: in the present case, the role of organizational attention focus in corporate philanthropic responses to an emergent human need.

Attention for Employees, Geography, and Philanthropy

The form of attention we measure is ‘visible attention,’ which we capture by analyzing the frequency with which specific topics are addressed in the annual report (Bouquet and Birkinshaw 2008). This content-based approach is in line with extant research showing that management communications reflect the perception and input of senior management and encompass the topics and issues that the company attends to (D’Aveni and MacMillan 1990; Levy 2005; Maula et al. 2013). Although such communications can have multiple purposes, they have been shown to capture concepts that are central to attention in the organization, and are indicative of managers’ strategies for sensemaking (Cho and Hambrick 2006; Kaplan 2008). Moreover, annual reports ‘send strong signals as to who the winners and losers are in their firms’ systems’ (Bouquet and Birkinshaw 2008, pp 579–580). We found annual reports for 431 companies among the Fortune Global 500 (the remainder being private or unlisted).

Bouquet and Birkinshaw (2008) operationalized visible attention as a single factor extracted from three ratios computed, respectively, as the total number of times a subsidiary country location was mentioned in the annual report (excluding references to currency and accounting standards) divided by the total number of words used in the annual report; the total number of times a subsidiary country location was mentioned divided by the total number of references made to the parent company’s nationality; and the total number of times a subsidiary country location was mentioned divided by the total number of references made to China. The use of China as a country comparator provided a realistic and objective sense of the relative attention afforded to a focal subsidiary in the MNE corporate world (p. 586).

In the same fashion, we measure employee attention focus by creating the following two ratios: (1) the number of times the words ‘employee’ or ‘employees’ were used in each firm’s 2003 annual report divided by the number of pages in the annual report; and (2) the number of times the words ‘employee’ or ‘employees’ were used in each firm’s 2003 annual report divided by the number of references to ‘profit,’ ‘profits,’ or ‘profitability.’ Our use of the latter terms as a denominator in the second ratio creates a ‘foil’ to employees just as Bouquet and Birkinshaw (2008) use ‘China’ as a foil for attention to specific geographic locations (see below). References to employees divided by the number of pages controls for the scope of the report and thus the range of other topics the annual report may make reference to, and controlling for references to profits forms a benchmark for the relative importance of topics because financial performance is always a central aspect of the annual report (Bouquet and Birkinshaw 2008). However, we were careful to exclude references to employees that were specifically linked to financially driven topics such as pension plans or wage expenses (see also the Appendix for additional information regarding the validity of this approach). In addition, lagging our measures by one year ensures that the data collected originated prior to the tsunami event and any subsequent donation, thus improving the prospects of causal inference (Baum 2006). The 431 annual reports analyzed together contained 27,093 references to employees (62.9 mentions per firm) and 25,512 references to profit or profitability (59.2 mentions per firm).

To capture geographic attention focus, we took each firm’s 2003 annual report and counted 1) the number of references to tsunami-stricken countriesFootnote 2 divided by the number of pages in the annual report; 2) the number of references to tsunami-stricken countries divided by the number of references to the home country in the annual report; and 3) the number of references to tsunami-stricken countries divided by the number of references to China. China as a country comparator provides a ‘realistic and objective sense of the relative attention’ afforded to other regions in the world (Bouquet and Birkinshaw 2008, p 586). For the Chinese companies in the sample, we used the number of references to the United States as the denominator in this third measure. We found 2,077 mentions of tsunami-stricken countries (4.8 on average per firm) and 40,098 references to each firm’s respective home country (93.0 on average per firm). By comparison, there were 3,771 references to China (8.8 on average).

To measure philanthropic attention focus, we searched annual reports for references to terms such as ‘philanthropy,’ ‘philanthropic,’ ‘charity,’ and ‘charitable.’ We found a total of 798 counts among our 431 cases, but noted that these observations were not well distributed across the cases. Specifically, 223 cases (52 percent) made no reference to philanthropy or charity at all, while the remaining 208 cases (48 percent) made on average 3.6 mentions per firm. Because the distribution of this measure was not appropriate for treatment as a continuous variable, we measured philanthropic attention focus as a dummy variable, taking a value of 1 for companies whose annual report made any mention of the aforementioned terms and a value of 0 for those whose annual reports did not. In total, we identified nearly 100,000 references in 431 annual reports that we then used to compute the attention-based items (Table 1).

Although our measures of employee and geographic attention are based on previously validated measures (Bouquet and Birkinshaw 2008), we performed a factor analysis (Principal Components analysis with Varimax rotation) on the items in Table 1 to confirm our expectations of the underlying factor structures. Prior to factor analysis, all measures were log-transformed due to skewness and then standardized. The results are reported in Table 2. The items loaded as expected, generating a two-factor structure that corresponds to the constructs. Although the Cronbach’s alpha for attention for tsunami-stricken countries is not high, the KMO measure and Bartlett’s test of sphericity indicate that the data are suitable for factor analysis. In addition, the items exhibit strong factor loadings with no bi-polarity or cross-loading.Footnote 3

Control Variables

We controlled for a number of other potential predictors of donation likelihood in response to the tsunami. First, we controlled for the number of subsidiaries an organization had in the disaster-stricken region, identified through Dun & Bradstreet’s Who Owns Whom database. Controlling for firms’ location-specific presence allows us to distinguish between the effects of presence and the effects of attention on philanthropic resource allocation (Bouquet and Birkinshaw 2008). Number of local subsidiaries is a continuous log-transformed variable since the overall incidence of subsidiaries in tsunami-stricken countries was relatively high (1,159 in total).

Second, we control for home region following Muller and Whiteman (2009) who show that significant differences exist in propensity to donate by region. We distinguished between North American firms, European firms, and Asia–Pacific firms. Further, we control for profitability and size as two key determinants of philanthropy (Adams and Hardwick 1998; Brammer and Millington 2004) and include sector dummies to control for sector-specific relevance of human needs (e.g., pharmaceuticals, fast-moving consumer goods or heavy equipment manufacturers may be more likely to donate, ceteris paribus, than other sectors) as well as industry-level isomorphic, peer-group benchmarking (Winn et al. 2008).

We also include a dummy for inclusion in the Dow Jones Sustainability Index (DJSI) to control for a history of experience with socially responsive practices such as corporate philanthropy. Although aggregate figures of actual corporate philanthropy donations would be a more desirable measure to control for prior behavior, such figures are not available at the firm level for a globally representative set of companies such as the Fortune Global 500. The DJSI, however, consists of companies evaluated as being in the top 10 percent of their sectors in terms of overall responsiveness, measured across dimensions such as corporate citizenship, labor relations, and human capital development, as well as codes of conduct, corporate governance, and environmental reporting. The DJSI is therefore broader than corporate philanthropy alone, but can still be considered a proxy for overall experience with responsiveness to needs in society (Ricart et al. 2005).Footnote 4

Results

We omitted five firms from regions other than North America, Europe. or Asia Pacific in order to avoid small subsample sizes, and also had to omit six cases with missing values. Our final dataset comprised 420 cases, of which 315 responded philanthropically to the tsunami disaster and 105 did not.Footnote 5 Descriptive statistics and correlations for all measures, with the exception of the industry dummies, are presented in Table 3. Table 3 shows that our three dimensions of attention focus are all positively related to donation likelihood, but also shows that the three attention foci exhibit either slightly negative bivariate correlations (geographic attention vs. employee attention, and geographic attention vs. philanthropic attention) or no correlation (employee attention vs. philanthropic attention). These initial observations lend support to our theoretical claim that organizations vary systematically in terms of their patterns of relative attention focus.

Table 4 reports logistic regression results for testing the Hypotheses 1 through 3b. We introduce our control variables in Model 1, main effects in Model 2, and then our interactions stepwise in Models 3 to 5. Model 2 returns significant, positive coefficients for geographic attention (odds ratio (OR) 2.03) and philanthropic attention (OR 2.18), showing that an increase in one-standard deviation of each measure doubles the ratio of the likelihood of donating versus not donating. These results lend support for Hypotheses 2a and 3a. The main effect for employee attention, however, is nonsignificant, and therefore Hypothesis 1 is not supported.

In models 3 and 4, we introduce the interaction effects associated with Hypotheses 2b and 3b independently followed by the full specification in Model 5. Model 5 shows significant, positive effects for the interaction between employee attention focus and geographic attention focus (OR 1.63) and employee attention focus and philanthropic attention focus (OR 3.28). Thus, both Hypotheses 2b and 3b are supported. In addition, diagnostics are strong, with the fully specified model explaining a good portion of the variance (Cox & Snell = 0.301; Nagelkerke = 0.446) and correctly predicting 83 % of the cases (Hosmer & Lemeshow statistic p value = 0.729). In sum, attention for places (tsunami-stricken countries) and practices (corporate philanthropy) interact with attention for people (employees) to predict philanthropic responses to the tsunami disaster.

We present the results for Hypotheses 2b and 3b in Figs. 2a and b, respectively. Figure 2 depicts the moderating effect of employee attention focus on the relationship between relative attention for the tsunami-stricken region in 2003 and the likelihood of subsequently donating in response to the 2004 tsunami (Hypothesis 2b). The figure shows that geographic attention focus had a particularly positive effect on donation likelihood when employee attention focus was high. In contrast, at low levels of geographic attention focus, employee attention focus had no effect on donation likelihood. Figure 2 shows the moderating effect of employee attention focus on the relationship between philanthropic attention focus and donation likelihood (Hypothesis 3b). The figure shows that philanthropic attention focus had a particularly strong effect on donation likelihood when employee attention focus was high. In contrast, the relationship between philanthropic attention focus and donation likelihood was much less pronounced at lower levels of employee attention focus. Thus, employee attention focus enhances the effects of both geographic attention focus and philanthropic attention focus on the likelihood of responding philanthropically to an emergent human need.

Discussion

In the present paper, we developed an identity-driven, attention-based framework to understand how organizational attention focused on people (employees), places (specific geographic locations), and practices (corporate philanthropy) interact to predict the likelihood of charitable responses to an emergent human need. First, based on the notion that identity drives organizations to manage internal and external relations in similar ways, we argued that attention focused on people inside the organization will be related to subsequent positive organizational behaviors directed outside the organization as well. Second, in line with research showing how organizations allocate resources to their subsidiaries overseas based on the amount of attention management pays to those subsidiaries, we proposed that attention for specific geographic locations predicts subsequent corporate philanthropy decisions in response to human needs in those locations. Third, noting that organizations sometimes engage established practices in the face of emergent issues and other times do not, we proposed that attention for those practices is an important understudied link between prior experience with a given practice and future engagement of that practice.

We found support for four of our five hypotheses, providing evidence that socially responsive resource allocations such as corporate philanthropy can be linked to the interactions between internally and externally directed attention focus. Although we found no evidence of a main effect of for employee attention focus on the likelihood of responding to the tsunami disaster with philanthropy (Hypothesis 1), we found effects for geographic attention focus and philanthropic attention focus (Hypotheses 2a and 3a). In addition, we found that employee attention focus positively moderated the effects of geographic and philanthropic attention foci on the likelihood of charitable donations (Hypotheses 2b and 3b). In the following sections, we discuss the implications of these findings for organization theory and management practice.

Theoretical Contributions

First, our attention-based perspective has implications for our understanding of organizational responsiveness to societal issues. Extending beyond prior research in which responsiveness is a function of generic external pressures (Brammer and Millington 2004) or management attention to specific categories of actors with specific attributes (Agle et al. 1999), our perspective shows that under certain conditions, attention for some actors (in our case, employees) can trigger responsiveness toward other actors (others outside the organization). This has implications for our understanding of the permeability of the organizational boundary when it comes to attention to societal issues, and the interplay between internal and external mechanisms in triggering organizational responsiveness to such issues. At the same time, our results show that the role of attention for employees is contingent upon externally directed attention foci. Specifically, attention for people requires attentions to specific locations and socially responsive practices in order to translate into a greater likelihood of responding philanthropically to an emergent human need. In so doing, we contribute to an employee-centric understanding of organizations’ social behaviors (Rupp 2011; van Buren 2005).

Second, we link research on corporate philanthropy to research on attention and organizations’ resource allocation decisions across geographic space. Thus far, the latter has focused on the importance of organization-external attention for organization-internal resource allocations (Bouquet and Birkinshaw 2008). We extend this body of research by considering the relationship between organization-internal attention and organization-external resource allocations, such as corporate philanthropy. Moreover, our results show that these effects exist above and beyond the effects of the ‘place embeddedness’ (Tilcsik and Marquis 2013) organizations have in relation to specific geographic locations. Thus, our attention-based view complements the prevailing institutional perspective, in which philanthropy is a function of ties to the local community (Galaskiewicz 1997, Marquis et al. 2007) or specific host countries’ institutional features (Brammer et al. 2009).

Third, our study contributes to research on the role of attention in the link between organizational identity and organizations’ social action. Our findings suggest that interactions between internally and externally directed attention focus form an important mechanism through which identity drives organizations to manage internal and external stakeholder relationships in parallel (Brickson 2005). In so doing, our results speak not only to the link between attention focus and action, but also to the hierarchy of attention mechanisms in driving action. Prior research has argued that ‘why’ attention mechanisms, or those related to goals and values, are superordinate to ‘how’ attention mechanisms, or those related to practices (Barreto and Patient 2013), in driving organizational behavior. In contrast, the present study suggests that ‘why’ attention mechanisms (a human focus) may only translate into action in the presence of ‘how’ attention mechanisms (corporate philanthropy). By highlighting these contingencies, we heed the call for greater exploration of the interactions between identity-based attention structures in driving organizations’ social actions (Maula et al. 2013).

Practical Implications

Our findings also have practical implications for management. First, while recent research has emphasized the role of managerial values as driver of organizational social behaviors (Agle et al. 1999), our results give more room to thinking about the role of employees in organizations’ social activities. Thus far, research has shown that greater managerial attention to employees engages employees’ prosocial identities and enhances belonging and affective commitment (Aguilera et al. 2007; Frey and Meier 2004; Grant et al. 2008). Our study reveals that the degree to which managers attend to employees has consequences for relations with actors outside the organization as well. While organizations, like people, may be subject to ‘fatigue’ when it comes to corporate philanthropy (Elliot 2008), employees have a role to play in keeping the organization focused on human issues.

Second, our study implies that organizations target their international corporate philanthropy activities similarly to the ways they target other forms of resource allocation: according to established patterns of attention focus. Although earlier research has established the importance of structural relationships between organizations and charitable causes in the communities where those organizations operate (Galaskiewicz 1997), our findings suggest that attention is an important additional element in the management of corporate philanthropy activities. In the same way that subsidiaries attract attention—and thus resources—through the exercise of voice (Bouquet and Birkinshaw 2008), charities championing human needs in specific locations may still be able to attract resources by steering companies’ attention toward those locations, even if the organization does not operate there.

Limitations and Future Research

While we were able to expose relationships between attention focus and the likelihood of corporate philanthropy in response to an emergent human need, we directed our efforts toward only one specific human need, the 2004 south Asian tsunami. Although the tsunami was a watershed event in global corporate philanthropy (Urma 2005) and thus a compelling natural setting to investigate responsiveness to emergent human needs, future research could take a more comprehensive look at corporate philanthropy across a range of causes over time. For instance, recent longitudinal research on a larger number of ‘mega-events’ suggests that while each event is unique, predictable patterns exist across such events and that such events precipitate longer-term shifts in giving (Tilcsik and Marquis 2013). Future research could investigate whether there was a significant effect in terms of a shift in companies’ overall patterns of giving toward countries in the region, and how long these effects lasted.

Our dataset is also subject to a number of limitations. For instance, our measure for attention to corporate philanthropy was dichotomous due to the nature of the data. While a dichotomous measure (‘companies that talked about philanthropy in their 2003 annual reports’ versus ‘companies that did not talk about philanthropy in their 2003 annual reports’) is more coarse-grained than a continuous measure, our findings show it still explains significant variance in the likelihood of responding charitably to the 2004 tsunami. Future research could, however, identify alternate measures of attention to corporate philanthropy, e.g., through company-internal documents. Similarly, we were unable to control directly for prior-giving due to the lack of comprehensive data on giving among the non-US firms in particular. Future research may aim at developing systematic corporate philanthropy data collection across countries.

Also, our data collection revealed that companies responded to the tsunami disaster through different forms of philanthropy (e.g., combinations of cash, goods, services, and employee time). Future research might explore factors related to these differences (Muller et al. 2014). In addition, our data did not provide information on how each company’s charitable giving was allocated across individual countries. Future research might link country-level attention focus with country-level giving (Brammer et al. 2009). Finally, while our quantitative approach builds on measures validated in previous qualitative research (e.g., Bouquet and Birkinshaw 2008), researchers might in future develop a qualitative study designed to flesh out some of the mechanisms we capture here in greater detail.

Finally, although theory on organizational identity provides numerous arguments in support of our empirical observation that organizations vary systematically in their attention focus (cf. Brickson 2005), it is beyond the scope of our study to investigate why patterns of attention focus exist in the configurations that they do. For instance, an employee attention focus is considerably more prominent in some organizations than others. These patterns of established attention focus will have developed over time, likely in interaction with other actors, and through experience and the perception of fit with organizational identity. Similarly, attention to a specific geographic location can be a function of that location’s importance to the organization in terms of sourcing or as an export market. Future research might investigate how the specific patterns of organizational attention for people, places, and practices that we identify here emerge and develop over time.

Conclusion

Research on corporate philanthropy has thus far left understudied the processes and mechanisms associated with the likelihood that a given organization would respond to a specific human need. We address this gap by explicating an attention-based, identity-driven framework in which dimensions of organizational attention focus explain why some firms take action in response to an emergent human need, while others do not. In our investigation of Fortune Global 500 firms’ donation activity following the 2004 South Asian tsunami disaster, we find that organizational attention focus on employees interacts with geographic attention and philanthropic attention focus to predict donation likelihood. Extending the corporate philanthropy literature beyond the well-established role of structural, contextual pressures, our results allow for a greater emphasis on organization-internal, attention-based mechanisms underlying organizations’ social behaviors, and a better understanding of the complexities of attention focus in organizational resource allocation more generally.

Notes

We note for completeness that these studies establish this independence empirically by controlling for sample selection bias (Heckman 1979), but do not theorize or hypothesize on donation likelihood.

Affected countries were those identified in the United Nation’s Flash Appeal for donations issued following the tsunami (United Nations 2005); specifically India, Indonesia, Sri Lanka, Myanmar, Indonesia, Thailand and Somalia.

We also tried a two-item factor for prior attention to tsunami-stricken countries, using the two items with the highest loadings (the number of references to tsunami-stricken countries divided by the number of pages in the annual report, and the number of references to tsunami-stricken countries divided by the number of references to China). These two items exhibit a bivariate (Spearman’s) correlation coefficient of 0.659. Since this two-item factor generated identical results as the three-item factor, we used the latter in our regressions.

As a robustness check, we also controlled for mention of the words ‘humanitarian’ and ‘disaster’ in firms’ annual reports to account for attention for specific types of human needs, but found no effects.

While we do not test on donation values, 278 specified a monetary value for their donations. Reported donation values ranged from $10,000 to $83.1 million, with a mean value of $2,172,640 and a median value of $1,000,000.

References

Adams, M., & Hardwick, P. (1998). An analysis of corporate donations: United Kingdom evidence. Journal of Management Studies, 35(5), 641–654.

Agle, B. R., Mitchell, R. K., & Sonnenfeld, J. A. (1999). Who matters to CEOs? An investigation of stakeholder attributes and salience, corporate performance, and CEO values. Academy of Management Journal, 42(5), 507–525.

Aguilera, R. V., Rupp, D. E., Williams, C. A., & Ganapathi, J. (2007). Putting the S back in corporate social responsibility: A multilevel theory of social change in organizations. Academy of Management Review, 32(3), 836–863.

Atienza, J., & Renz, L. (2006). International grantmaking update: A snapshot of US Foundation trends, Foundation Center Prepared in Cooperation with the Council on Foundations. Retrieved March 22, 2006, from http://cof.org/files/Documents/International_Programs/2006%20Publications/IntlUpdateOct06.pdf.

Bansal, P. (2003). From issues to actions: The importance of individual concerns and organizational values in responding to natural environmental issues. Organization Science, 14(5), 510–527.

Bansal, P., & Roth, K. (2000). Why companies go green: A Model of ecological responsiveness. Academy of Management Journal, 43(4), 717–736.

Barnett, M. L. (2008). An attention-based view of real options reasoning. Academy of Management Review, 33(3), 606–628.

Barreto, I., & Patient, D. (2013). Toward a theory of intraorganizational attention based on desirability and feasibility factors. Strategic Management Journal, 34(6), 687–703.

Baum, C. (2006). An introduction to modern econometrics using stata. College Station: Stata Press.

Bouquet, C., & Birkinshaw, J. (2008). Weight versus voice: How foreign subsidiaries gain attention from corporate headquarters. Academy of Management Journal, 51(3), 577–601.

Bowen, D. E., Gilliland, S. W., & Folger, R. (2000). HRM and service fairness: How being fair with employees spills over to customers. Organizational Dynamics, 27(3), 7–23.

Brammer, S., & Millington, A. (2004). The development of corporate charitable contributions in the UK: A stakeholder analysis. Journal of Management Studies, 41(8), 1411–1434.

Brammer, S., & Millington, A. (2005). Corporate reputation and philanthropy: An empirical analysis. Journal of Business Ethics, 61(1), 29–44.

Brammer, S. J., & Pavelin, S. (2006). Corporate reputation and social performance: The importance of fit. Journal of Management Studies, 43(3), 435–455.

Brammer, S. J., Pavelin, S., & Porter, L. A. (2009). Corporate charitable giving, multinational companies and countries of concern. Journal of Management Studies, 46(4), 575–596.

Brickson, S. L. (2005). Organizational identity orientation: Forging a link between organizational identity and organizations’ relations with stakeholders. , Administrative Science Quarterly, 50(4), 576–609.

Bundy, J., Shropshire, C., & Buchholtz, A. (2013). Strategic cognition and issue salience: Towards an explanation of firm responsiveness to stakeholder concerns. Academy of Management Review, 38(3), 352–376.

Chattopadhyay, P., Glick, W. H., & Huber, G. P. (2001). Organizational actions in response to threats and opportunities. Academy of Management Journal, 44(5), 937–955.

Cho, T. S., & Hambrick, D. C. (2006). Attention as the mediator between top management team characteristics and strategic change: The Case of airline deregulation. Organization Science, 17(4), 453–469.

Cohen-Charash, Y., & Spector, P. (2001). The role of justice in organizations: A meta-analysis. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 86(2), 278–321.

Crampton, W., & Patten, D. (2008). Social responsiveness, profitability and catastrophic Events: Evidence on the corporate philanthropic response to 9/11. Journal of Business Ethics, 81(4), 863–873.

Cropanzano, R., Bowen, D. E., & Gilliland, S. W. (2007). The management of organizational justice. Academy of Management Perspectives, 21(4), 34–48.

D’Aveni, R. A., & MacMillan, I. C. (1990). Crisis and the content of managerial communications: A study of the focus of attention of top managers in surviving and failing firms. Administrative Science Quarterly, 35, 634–657.

Dane, E. (2013). Things seen and unseen: Investigating experience-based qualities of attention in a dynamic work setting. Organization Studies, 34(1), 45–78.

Davenport, T. H., & Beck, J. C. (2001). The attention economy: Understanding the new currency of business. Cambridge: Harvard Business Press.

Dunfee, T. W. (2006). Do Firms with unique competencies for rescuing victims of human catastrophes have special obligations? Corporate responsibility and the AIDS catastrophe in Sub-Saharan Africa. Business Ethics Quarterly, 16(2), 185–210.

Dutton, J. E., & Jackson, S. E. (1987). Categorizing strategic issues: Links to organizational action. Academy of Management Review, 12(1), 76–90.

Dutton, J. E., & Dukerich J. M. (1991). ‘Keeping an eye on the mirror: Image and identity in organizational adaptation', Academy of Management Journal, 34(3), 517–554.

Dutton, J. E., Dukerich, J. M., & Harquail, C. V. (1994). Organizational images and member identification. Administrative Science Quarterly, 39, 239–263.

Dutton, J. E., Ashford, S. J., O’Neill, R. M., & Lawrence, K. A. (2001). Moves that matter: Issue Selling and organizational change. Academy of Management Journal, 44(4), 716–736.

Dutton, J. E., Worline, M. C., Frost, P. J., & Lilius, J. (2006). Explaining compassion organizing. Administrative Science Quarterly, 51(1), 59–96.

Edvinsson, L., & Sullivan, P. (1996). Developing a model for managing intellectual capital. European Management Journal, 14(4), 356–364.

Elliot, J. (2008). With donors worn out funding dries up. Houston Chronicle, Sept 18. Retrieved January 14, 2010, from http://foundationcenter.org/pnd/news/story.jhtml?id=228100002.

Flamholtz, E. G., Bullen, M. L., & Hua, W. (2002). Human resource accounting: A historical perspective and future implications. Management Decision, 40(10), 947–954.

Foreman, P., & Whetten, D. A. (2002). ‘Members’ identification with multiple-identity organizations. Organization Science, 13(6), 618–635.

Frey, B. S., & Meier, S. (2004). Pro-social behavior in a natural setting. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 54(1), 65–88.

Fritz Institute. (2005). Logistics and the effective delivery of humanitarian relief. Retrieved December 22, 2005, from http://www.fritzinstitute.org/PDFs/Programs/TsunamiLogistics0605.pdf.

Galaskiewicz, J. (1997). An urban grants economy revisited: Corporate charitable contributions in the twin cities, 1979-81, 1987-89. Administrative Science Quarterly, 42, 445–471.

Galaskiewicz, J., & Burt, R. S. (1991). Interorganization Contagion in corporate philanthropy. Administrative Science Quarterly, 36, 88–105.

Glynn, M. A., & Abzug, R. (2002). Institutionalizing identity: Symbolic isomorphism and organizational names. Academy of Management Journal, 45(1), 267–280.

Grant, A. M. (2012). Giving time, time after time: Work design and sustained employee participation in corporate volunteering. Academy of Management Review, 37(4), 589–615.

Grant, A. M., Dutton, J. E., & Rosso, B. D. (2008). Giving commitment: Employee support programs and the prosocial sensemaking process. Academy of Management Journal, 51(5), 898–918.

Hair, J. F., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L., & Black, W. C. (1998). Multivariate analysis. Englewood: Prentice Hall International.

Hargadon, A., & Fanelli, A. (2002). Action and possibility: Reconciling dual perspectives of knowledge in organizations. Organization Science, 13(3), 290–302.

Heckman, J. J. (1979). Sample selection bias as a specification error. Econometrica, 47(1), 153–161.

Hoffman, A. J., & Ocasio, W. (2001). Not all events are attended equally: Toward a middle-range theory of industry attention to external events. Organization Science, 12(4), 414–434.

Hosmer, D. W., & Lemeshow, S. (2000). Applied Logistic Regression (2nd ed.). New York: Wiley.

IBLF. (2005). Best intentions complex realities: Business and the lessons from the tsunami. International Business Leaders Forum.

Kaplan, S. (2008). Cognition, capabilities, and incentives: Assessing firm response to the fiber-optic revolution. Academy of Management Journal, 51(4), 672–695.

Kellett, J. B., Humphrey, R. H., & Sleeth, R. G. (2006). Empathy and the emergence of task and relations leaders. The Leadership Quarterly, 17(2), 146–162.

Lester, D. L., Parnell, J. A., & Carraher, S. (2010). Assessing the desktop manager. Journal of Management Development, 29(3), 246–264.

Lev, B., Petrovits, C., & Radhakrishnan, S. (2010). Is doing good good for you? How corporate charitable contributions enhance revenue growth. Strategic Management Journal, 31(2), 182–200.

Levinthal, D. A., & March, J. G. (1993). The myopia of learning. Strategic Management Journal, 14, 95–112.

Levy, O. (2005). The influence of top management team attention patterns on global strategic posture of firms. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 26(7), 797–819.

Liebowitz, J., & Suen, C. Y. (2000). Developing knowledge management metrics for measuring intellectual capital. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 1(1), 54–67.

Lilius, J., Kanov, J., Dutton, J., Worline, M., & Maitlis, S. (2011). Compassion revealed: What we know about compassion at work (and where we need to know more). In K. Cameron & G. Spreitzer (Eds.), Oxford handbook of positive organizational scholarship (pp. 273–287). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Madden, L. T., Duchon, D., Madden, T. M., & Plowman, D. A. (2012). Emergent Organizational capacity for compassion. Academy of Management Review, 37(4), 689–708.

March, J. G., & Shapira, Z. (1992). Variable risk preferences and the focus of attention. Psychological Review, 99(1), 172.

Marquis, C., Glynn, M. A., & Davis, G. F. (2007). Community isomorphism and corporate social action. Academy of Management Review, 32(3), 925–945.

Maula, M. V. J., Keil, T., & Zahra, S. A. (2013). Top management’s attention to discontinous technological change. Organization Science, 24(13), 926–947.

McKendrick, D. G., Jaffee, J., Carroll, G. R., & Khessina, O. M. (2003). In the bud? Disk array producers as a (possibly) emergent organizational form. Administrative Science Quarterly, 48(1), 60–93.

Muller, A., & Whiteman, G. (2009). Exploring the geography of corporate philanthropic disaster response: A study of fortune global 500 firms. Journal of Business Ethics, 84(4), 589–603.

Muller, A. R., Pfarrer, M. D., & Little, L. M. (2014). A theory of collective empathy in corporate philanthropy decisions. Academy of Management Review, 39(1), 1–21.

Nadkarni, S., & Barr, P. S. (2008). Environmental context, managerial cognition, and strategic action: An integrated view. Strategic Management Journal, 29(13), 1395–1427.

Nag, R., Corley, K. G., & Gioia, D. A. (2007). The intersection of organizational identity, knowledge, and practice: Attempting strategic change via knowledge grafting. Academy of Management Journal, 50(4), 821–847.

Nelson, R. R., & Winter, S. G. (1982). The Schumpeterian tradeoff revisited. American Economic Review, 72(1), 114–132.

Ocasio, W. (1997). Towards an Attention-based View of the Firm. Strategic Management Journal, 18(S1), 187–206.

Petrovits, C. M. (2006). Corporate-sponsored foundations and earnings management. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 41(3), 335–362.

Rabinovich, A., Morton, T. A., Postmes, T., & Verplanken, B. (2009). Think global, act local: The effect of goal and mindset specificity on willingness to donate to an environmental organization. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 29(4), 391–399.

Rerup, C. (2009). Attentional triangulation: Learning from unexpected rare crises. Organization Science, 20(5), 876–893.

Ricart, J. E., Rodríguez, M. Á., & Sánchez, P. (2005). Sustainability in the boardroom: An empirical examination of DowJones sustainability world index leaders. Corporate Governance, 5(3), 24–41.

Romanelli, E., & Khessina, O. M. (2005). Regional industrial identity: Cluster configurations and economic development. Organization Science, 16(4), 344–358.

Rousseau, D. M., & Wade-Benzoni, K. A. (1994). Linking Strategy and human resource practices: How employee and customer contracts are created. Human Resource Management, 33(3), 463–489.

Rupp, D. E. (2011). An employee-centered model of organizational justice and social responsibility. Organizational Psychology Review, 1(1), 72–94.

Saiia, D. H., Carroll, A. B., & Buchholtz, A. K. (2003). Philanthropy as strategy: When corporate charity “begins at home”. Business and Society, 42(2), 169–201.

Sharma, S. (2000). Managerial interpretations and organizational context as predictors of corporate choice of environmental strategy. Academy of Management Journal, 43(4), 681–697.

Su, J., & He, J. (2010). Does giving lead to getting? Evidence from Chinese private enterprises. Journal of Business Ethics, 93(1), 73–90.

Tilcsik, A., & Marquis, C. (2013). Punctuated generosity how mega-events and natural disasters affect corporate philanthropy in US communities. Administrative Science Quarterly, 58(1), 111–148.

United Nations. (2005). Indian ocean earthquake-tsunami flash appeal. New York: Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs.

Urma, V. (2005). In post-Tsunami Katrina world corporate America seeks bigger role in relief operations, Associated Press Newswire. Retrieved December 19, 2005, from http://www.corporatephilanthropy.org/press/PR/AP121905relief.pdf.

Useem, M. (1988). Market and institutional factors in corporate contributions. California Management Review, 30(2), 77–88.

Van Buren, H. J., III. (2005). An employee-centered model of corporate social performance. Business Ethics Quarterly,. doi:10.5840/beq200515447.

Wang, H., Choi, J., & Li, J. (2008). Too little or too much? Untangling the relationship between corporate philanthropy and firm financial performance. Organization Science, 19(1), 143–159.

Wang, H., & Qian, C. (2011). Corporate philanthropy and corporate financial performance: The roles of stakeholder response and political access. Academy of Management Journal, 54(6), 1159–1181.

Winn, M. I., MacDonald, P., & Zietsma, C. (2008). Managing industry reputation: The dynamic tension between collective and competitive reputation management strategies. Corporate Reputation Review, 11(1), 35–55.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Jane Dutton, Willie Ocasio, Mike Pfarrer, and Arno Kourula for their invaluable comments on earlier drafts of this manuscript, as well as editor Joëlle Vanhamme and the two anonymous reviewers for their guidance and feedback.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

We argue that our measure of employee attention focus represents positive attention for employees by management. To test the validity of this claim, we conducted two tests. First, we collected data on the 2004 ‘Best Places to Work’ (www.greatplacetowork.com) for all 25 countries with firms in the Fortune Global 500 represented in our sample. Inclusion in the list of ‘Best Places to Work,’ which is based on employee self-reporting, can be seen as an indicator that an organization attends positively to the needs and desires of its employees. We found 63 ‘Best Places to Work’ among our 431 Fortune Global 500 firms, and observed that these firms have a 25 percent higher incidence of employee references per page of the annual report than the remaining 368 firms (0.63 mentions per page versus 0.5 mentions per page), and that this difference is statistically significant at the p < 0.05 level (t statistic = −2.862). Further, our two-item factor for employee attention focus (see below) also differed significantly between the two groups at p < 0.05 (t statistic = −2.125). In other words, companies rated the ‘Best Places to Work’ allocate more attention to their employees in their annual reports than do other firms. This provides strong support for the validity of our measure of employee attention in the annual report as a proxy for positive management attention toward employees in the organization.

Second, we explored whether our measure correlates with third-party assessments of positive treatment of employees through the Kinder, Lydenberg, and Domini (KLD) database. KLD, a well-known and frequently used database of firms’ social performance, records firms’ ‘strengths,’ and ‘weaknesses’ across seven key dimensions of firm-level social responsibility, one of which is ‘employee relations.’ However, our sample (the global 2004 Fortune 500 listing) only partially overlaps with the KLD database, which is restricted to the US firms only. We were able to identify 109 US firms in our sample that are also in the KLD database (using data from the year 2003, consistent with our other measures). For the 109 US firms in our sample with KLD data, there are 54 firms with an ‘employee relations strengths’ score of 0, and 55 with an ‘employee relations strengths’ score of 1 or higher (the maximum score is 4). For the 55 US firms with at least one recorded employee relations strength, the median employee-attention focus score (i.e., the measure we use in this paper) is 0.44. In contrast, the median employee-attention focus score for the 54 US firms with no recorded employee relations strengths is 0.10. These medians are statistically different at p = 0.044.

In other words, our employee attention focus measure is significantly higher for the US firms that have KLD employee-related strengths than it is for those US firms without KLD employee-related strengths. Not surprisingly, the incidence of the US firms with KLD employee-related strengths is also much higher among the firms considered “Best Places to Work” (p < 0.001) than among the firms not on that list. In sum, both employee self-reporting (‘Best Places to Work’) and independent third-party auditing (KLD’s ‘employee relations’ score) provide support for our view that the prominence of employees as a topic in the annual report is an expression of positive forms of attention by management for the organization’s employees.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Muller, A., Whiteman, G. Corporate Philanthropic Responses to Emergent Human Needs: The Role of Organizational Attention Focus. J Bus Ethics 137, 299–314 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2556-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2556-x