Abstract

The goal of this paper is to defend open theism vis-à-vis its main competitors within the family of broadly classical theisms, namely, theological determinism and the various forms of non-open free-will theism, such as Molinism and Ockhamism. After isolating two core theses over which open theists and their opponents differ, I argue for the open theist position on both points. Specifically, I argue against theological determinists that there are future contingents. And I argue against non-open free-will theists that future contingency is incompatible with the future’s being epistemically settled for God. This paper is a follow-up to the author’s Rhoda (Religious Studies, 2008) which was delivered during the APA Pacific 2007 Mini-Conference on Models of God.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The precise nature of God’s necessity is a matter of some debate among theists. Some think that God is necessary in the broadly logical sense of existing in all possible worlds. Others think that God is ‘metaphysically’ necessary in the sense of existing in all non-empty possible worlds, such that if anything exists, then God does too. It is not necessary for my purposes to take a stand on this debate, so I’ll simply take ‘God exists necessarily’ to mean that God is at least metaphysically necessary.

By creation ex nihilo I simply mean that God did not fashion creation out of any preexisting matter or stuff á la Plato’s Demiurge.

The last clause is meant to exclude process theism. Open theists have generally been quite explicit that they mean to stay within the broadly classical theistic tradition. See esp. Cobb and Pinnock (2000).

Rhoda (2008).

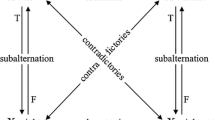

The future is ‘causally open’ with respect to state of affairs X, present time t, and future time t* if and only if, given all that exists as of t, it is really possible both that X obtains at t* and that X does not obtain at t*. In other words, whether X obtains at t* or not is, as of t, a future contingent.

The future is ‘epistemically open’ for person S at time t with respect to some conceivable future state of affairs X if and only if for some future time t* neither “X will obtain at t*” nor “X will not obtain at t*” is infallibly known by S at t. The future is ‘epistemically settled’ for S at t in all and only those respects in which it is not epistemically open for S at t.

By (1) God exists and has maximal possible knowledge. Hence, the future must be epistemically settled for God if such knowledge is possible for him to have. By (2) and (3), however, there is knowledge that God cannot have, namely, he cannot know of a future contingent event that it ‘will’ happen or that it ‘will not’ happen.

The term ‘free-will theism’ refers to the family of views defined by commitment to (1) broadly classical theism and (2) future contingency, with the latter understood to entail creaturely libertarian freedom. See Basinger (1996). Since open theists generally accept that some creatures have libertarian freedom, they qualify as free-will theists. ‘Non-open free-will theists’ are distinguished from open theists by their rejection of (3) and (4).

Especially notable in this regard is Hasker (1989).

The future is ‘alethically open’ at time t with respect to some conceivable future state of affairs X if and only if for some future time t* neither “X will obtain at t*” nor “X will not obtain at t*” is true at t. The future is ‘alethically settled’ at t with respect to X just in case it is not alethically open at t with respect to X.

For a presentation of this charge see Ware (2000), ch. 4.

For a philosophical overview of quantum mechanics, see Sklar (1992), 202ff.

See, for example, Shimony (1988).

Kane (2006), ch. 11.

Westminster Confession of Faith 3.1. The classic defense of theological determinism is Jonathan Edwards’ 1754 work Freedom of the Will.

Cf. Romans 9:20.

For example, Wykstra (1984).

The sophisticated skeptical theist proposes that we may not be in a good epistemic position to distinguish between genuinely gratuitous evils and ones that are only apparently so, where a ‘gratuitous evil’ is one that is neither necessary to bring about a greater good nor necessary to avert a greater evil. The worry is that reliance on skeptical theism as a carte blanche response to the evidential problem of evil requires shifting from the moderate and plausible “we are often not in a good epistemic position to identify gratuitous evils” to the extreme and implausible “we are almost never in a good epistemic position, etc.” That this seriously undermines our moral confidence is forcefully argued by Hasker (2004), ch. 3.

Prior develops the ‘Ockhamist’/‘Peircean’ distinction in Prior (2003), 39–58.

Fredosso (1988), 71–72.

If it’s not clear that the claim is not assertible for S because 50–50 seems close enough, then change the example to, say, roulette, in which the odds of the ball’s landing on a particular number are 1 in 38. Were a person to say in this context “The ball will land on 20” we would naturally be hesitant to construe that as reflecting a genuine belief on her part since we know, and presume that she also knows, that it is much more likely that the ball not land on 20. But if she doesn’t really believe what she’s saying, then it’s not a genuine prediction. It’s predictive in form, but not in content.

Prior (2003), 49.

Compare Ockham’s frank admission that “It is impossible to express clearly the way in which God knows future contingents” (Ockham 1983, p. 50).

References

Basinger, D. (1996). The case for freewill theism: A philosophical assessment. Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press.

Cobb, J. B., & Pinnock, C. H. (Eds.) (2000). Searching for an adequate God: A dialogue between process and free will theists. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans.

Fischer, J. M. (Ed.) (1989). God, foreknowledge and freedom. Stanford, CA: Stanford Univ. Press.

Fredosso, A. J. (1988). Introduction. In Luis de Molina, On divine foreknowledge: Part IV of the Concordia, tr. A. J. Fredosso (pp. 1–81). Ithaca: Cornell Univ. Press.

Hasker, W. (1989). God, time, and knowledge. Ithaca, NY: Cornell Univ. Press.

Hasker, W. (2001). The foreknowledge conundrum. International Journal for the Philosophy of Religion, 50, 97–114.

Hasker, W. (2004). Providence, evil, and the openness of God. London: Routledge.

Kane, R. (2006). A contemporary introduction to free will. Oxford, Oxford: Univ. Press.

Ockham, W. (1983). Predestination, God’s foreknowledge, and future contingents, 2nd ed. Tr. M. M. Adams & N. Kretzmann. Indianapolis: Hackett.

Prior, A. N. (2003). The formalities of omniscience. In Per Hasle et al. (Eds.), Papers on time and tense (pp. 39–58). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Rhoda, A. R. (2008). Generic open theism and some varieties thereof. Religious Studies (in press).

Shimony, A. (1988). The reality of the quantum world. Scientific American, 258, 46–53.

Sklar, L. (1992). Philosophy of physics. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Ware, B. A. (2000). God’s lesser glory: The diminished God of open theism. Wheaton, IL: Crossway.

Wykstra, S. J. (1984). The Humean obstacle to evidential arguments from evil: On avoiding the evils of ‘appearance’. International Journal for Philosophy of Religion, 16, 73–93.

Zagzebski, L. (1991). The dilemma of freedom and foreknowledge. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rhoda, A. The Philosophical Case for Open Theism. Philosophia 35, 301–311 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11406-007-9078-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11406-007-9078-4