Abstract

Among the results of recent investigation of epistemic intuitions by experimental philosophers is the finding that epistemic intuitions show cultural variability between subjects of Western, East Asian and Indian Sub-continent origins. In this paper I ask whether the finding of this variation is evidence of cross-cultural variation in the folk-epistemological competences that give rise to these intuitions—in particular whether there is evidence of variation in subjects’ explicit or implicit theories of knowledge. I argue that positing cross-cultural variation in subjects’ implicit theories of knowledge is not the only possible explanation of the intuitions, and I suggest other explanations, including the hypothesis that each subject’s implicit theory of knowledge might contain a heterogeneous set of heuristics for ascribing knowledge. Variation in intuitions, then, might be the result of within-subject heterogeneity rather than across-subject heterogeneity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Asking exactly how our explicit views about knowledge, truth and evidence vary across cultures diachronically and geographically is of course very interesting, and has been studied (see Shapin 1994).

Perner (1991, ch 7) lists these two principles as ones that children master early.

This term is due to Nadelhoffer and Nahmias (2007), as are the labels for the other subgroups within experimental philosophy.

This label is not perfect, though, since it potentially misleadingly associates experimental descriptivists and experimental analysts. ‘Descriptivism’ is the name of a thesis about the semantics of theoretical terms that underwrites one way of justifying the program of experimental analysis.

This is taken from Nichols et al. (2003).

For this study, ‘Western’ subjects were US undergraduates of European ancestry; ‘East Asian’ subjects were either subjects in East Asia (China, Japan and Korea) or US undergraduates who were either natives of East Asia, or first or second generation immigrants.

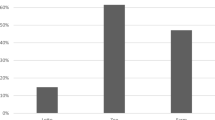

On the Truetemp Case, 32% of Western subjects had the intuition that Charles knew; 68% of Western subjects had the intuition that he didn’t know (n = 189). In contrast, 12% of East Asian subjects had the intuition that Charles knew; 88% of EA subjects had the intuition that he didn’t know (n = 25).

On the Gettier Case, 26% of Western subjects had the intuition that Bob knew; 74% of Western subjects had the intuition that he didn’t know (n = 66). In contrast, 57% of East Asian subjects had the intuition that Bob knew; 43% of EA subjects had the intuition that he didn’t know (n = 23).

That two subjects are using the same flow chart but making a different choice at some point on it does not imply that they only differ in some not folk-epistemological respect: judging whether Bob could easily have been wrong might itself be a folk epistemological judgement—performed using some folk epistemological heuristic for calculating reliability, for example. Thanks to Christophe Heintz for clarifying this point for me.

References

Alexander, J., and J.M. Weinberg. 2003. Analytic epistemology and experimental philosophy. Philosophy Compass 20(1): 56–80.

Astington, J.W., J. Pelletier, and B. Homer. 2002. Theory of mind and epistemological development: The relation between children’s second-order false-belief understanding and their ability to reason about evidence. New Ideas in Psychology 20: 131–144.

Chisholm, R. 1966. Theory of knowledge. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall.

Cummins, R. 1998. Reflections on reflective equilibrium. In Rethinking intuition, 1998, ed. M. DePaul and W. Ramsey. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

Gettier, E. 1963. Is justified true belief knowledge? Analysis 23: 121–123.

Gigerenzer, G., P. Todd, et al. 1999. Simple heuristics that make us smart. New York: Oxford University Press.

Hardy-Vallée, B., and B. Dubreuil. This issue. Folk epistemology as normative social cognition. Review of Philosophy and Psychology. doi:10.1007/s13164-009-0020-5.

Harris, P. 2004. Trust in testimony, children’s use of true and false statements. Psychological Science 10: 694–698.

Hofer, B., and P.R. Pintrich. 1997. The development of epistemological theories: Beliefs and knowledge and knowing and their relation to learning. Review of Educational Research 67: 88–140.

Hofer, B., and P.R. Pintrich (eds.). 2002. Personal epistemology: The psychology of beliefs about knowledge and knowing. Mahwah: Erlbaum.

Jackson, F. 1997. From metaphysics to ethics. Oxford: OUP.

Knobe, J. 2006. The concept of intentional action: A case study in the uses of folk psychology. Philosophical Studies 130: 203–231.

Koenig, M. 2002. Children’s understanding of belief as a normative concept. New Ideas in Psychology 20: 107–130.

Lewis, D. 1972. Psychophysical and theoretical identifications. Australasian Journal of Philosophy 50: 249–258.

Miller, S.A. 2000. Children’s understanding of preexisting differences in knowledge and belief. Developmental Review 20: 227–282.

Montgomery, D.E. 1992. Review: Young children’s theory of knowing: the development of folk epistemology. Developmental Review 12: 410–430.

Nadelhoffer, T. 2006. On trying to save the simple view. Mind & Language 21(5): 565–586.

Nadelhoffer, T., and T. Matveeva. (2009) Positive illusions, perceived control and the free will debate. Mind and Language 24(5): 495–522.

Nadelhoffer, T., and E. Nahmias. (2007). The past and future of experimental philosophy. Philosophical Explorations 10(2): 123–149.

Nahmias, E., S. Morris, T. Nadelhoffer, and J. Turner. 2006. Is incompatibilism intuitive? Philosophy and Phenomenological Research LXXIII(1): 28–53.

Nichols, S., and J. Knobe. 2007. Moral responsibility and determinism: The cognitive science of folk intuitions. Nous 41: 663–685.

Nichols, S., S. Stich, and J.M. Weinberg. 2003. Metaskepticism: meditations in ethno-epistemology. In The skeptics, ed. S. Luper, 227–247. Aldershot: Ashgate Press.

Perner, J. 1991. Understanding the representational mind. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Perry, W.G. 1970. Forms of intellectual development and ethical development in the college years: A scheme. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

Proust, J. 2007. Metacognition and metarepresentation: Is self-directed theory of mind a precondition for metacognition? Synthese 159: 271–295.

Shapin, S. 1994. A social history of truth: Civility and science in seventeenth century England. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Sperber, D. 1996. Explaining culture. Oxford: Blackwell.

Sperber, D. 2005. An evolutionary perspective on testimony and argumentation. Philosophical Topics 29: 401–413.

Spicer, F. 2008. Are there any conceptual truths about knowledge? Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society CVIII(part I): 43–60.

Stich, S., and I. Ravenscroft. 1994. What is folk psychology? Cognition 50: 447–468.

Swain S., J. Alexander, and J.M. Weinberg. (2008) The instability of philosophical intuitions: Running hot and cold on Truetemp. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 76(1): 138–155.

Weinberg, J.M., S. Nichols, and S. Stich. 2001. Normativity and epistemic intuitions. Philosophical Topics 29: 429–460.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to an anonymous referee for very helpful comments on earlier drafts of this paper. This paper was written while on leave funded by the AHRC as part of the ESF’s Eurocores program; thanks to both institutions for their support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Spicer, F. Cultural Variations in Folk Epistemic Intuitions. Rev.Phil.Psych. 1, 515–529 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13164-010-0023-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13164-010-0023-2