Abstract

In this paper I am concerned with risk–benefit analysis; that is, the comparison of the risks of a situation to its related benefits. We all face such situations in our daily lives and they are very common in medicine too, where risk–benefit analysis has become an important tool for rational decision-making. This paper explores risk–benefit analysis from a logical point of view. In particular, it seeks a better understanding of the common view that decisions should be made by weighing risks against benefits and that an option should be chosen if its benefits outweigh its risks. I devote a good deal of this paper scrutinizing this popular view. Specifically, I demonstrate that this mode of reasoning is logically faulty if “risk” and “benefit” are taken in their absolute sense. But I also show that arguing in favour of an action because its benefits outweigh its risks can be valid if we refer to incremental risks and benefits.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Be it noted that, strictly speaking, only quantitative risk-benefit analysis allows calculating a so-called risk:benefit ratio. For example, Roberts (1985) discusses in a quantitative study the problem of food-borne diseases and their prevention by irradiation. He holds that “both irradiation of chicken and pork appear to have a favourable benefit/cost ratio of 2 or more” (1985, 963). However, some authors use the term “risk:benefit ratio” also in their qualitative analyses (e.g., Allen and Luger 2002; Zuppa and de Luca 2003). But this use is not helpful since it can only be metaphorical.

See also Bogousslavsky (1996), Pochin (1982), and Wu (2004). Sieber and Adamson, moreover, hold regarding maintenance therapy in myeloma: “Even if multiple myeloma patients treated with melphalan are at a higher risk of developing acute leukaemia than is the general population [an incremental risk], the consensus among clinicians appears to be that the increases in survival time and in the quality of life of melphalan-treated patients far outweigh the risk of drug-induced acute leukaemia” (1975, 557).

Compare also Buchanan and Miller (2006) and Orme (1990), who argues for the use of thiazides in treating hypertension because the benefits outweigh its risks. Among the risks is the fact that thiazide diuretics cause hypokalaemia (an absolute risk) and may increase the serum cholesterol concentration (an incremental risk).

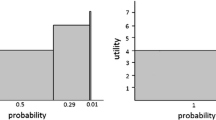

Attitudes toward risk differ. Some people are risk-seeking, but research suggests that most of us are somewhat risk-averse. If a person is neither risk-seeking nor risk-averse, he or she is said to be risk-neutral.

There is a fundamental disagreement in the philosophical literature over the conclusion of practical reasoning. Some hold that it is an action, while others reject this as inadequate and contend that it must be an intention, a decision, or an imperative. Throughout this essay, I shall assume that the conclusion of a piece of practical reasoning is an intentional attitude (e.g., your wanting that x is performed or your preferring x to y). In ordinary speech, such conclusions can be expressed in different ways—e.g., by holding that one should do something or that it would be better to do it. That is to say, the conclusion “women should receive tamoxifen treatment” is the expression of the reasoner’s preference for this therapy.

Some authors take “risk” as synonymous with “probability.” Strictly speaking, however, the probability of a bad outcome is in risk–benefit analysis only one component of the risk associated with an option. To the different meanings of “risk” and “benefit,” compare Hansson (2005), Iltis (2005), and Pochin (1982).

The example has been adapted from Hammond, Keeney, and Raiffa (1999, 131–133). I have used a slightly different version of this example in another paper, albeit in a different context.

It should be noticed that, in medicine, we are often facing problems so vague that we cannot assign probabilities. In such cases, we need to rely on nonprobabilistic risk–benefit analysis, which is based solely on the value of the outcomes and ignores their probabilities. In nonprobabilistic risk–benefit analysis, we have only possibilities available. Holding that an event is possible is making an extremely weak claim. We are only saying that it is not impossible that the event occurs, which, in turn, is to say that it is not necessary that it does not occur. Nonprobabilistic problems occur frequently in medicine. For example, the World Medical Association holds that “if the risk is entirely unknown, then the researcher should not proceed with the [research] project” (2009, 104–105); and in the 1970s, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration denied approval of Depo-Provera for use as a contraceptive partly because it was unclear how likely a higher incidence of breast cancer, found in beagle dogs, was applicable to humans (Guttmacher Institute 1978). Since there is no space here to go into the details of nonprobabilistic risk–benefit analysis, I can only mention that the “benefit-outweighs-risk” mode of reasoning can be shown to be valid in nonprobabilistic reasoning, too, if we reconstruct the reasoning by ignoring probabilities (which results in an analysis akin to the application of Laplace’s maxim of equal probability).

References

Allen, B.R., and T.A. Luger. 2002. Risk:benefit ratio is important in treating atopic dermatitis. British Medical Journal 325(7370): 970.

Allison, S.P. 1994. Costs outweigh benefits. British Medical Journal 309(6967): 1499–1500.

Anderson, E. 1993. Value in ethics and economics. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Bogousslavsky, J. 1996. Thrombolysis in acute stroke: Defining the risk to benefit ratio for individual patients remains impossible. British Medical Journal 313(7058): 640–641.

Brody, H. 1998. Double effect: Does it have a proper use in palliative care? Journal of Palliative Medicine 1(4): 329–331.

Buchanan, D.R., and F.G. Miller. 2006. A public health perspective on research ethics. Journal of Medical Ethics 32(12): 729–733.

Ellison, R.C. 2002. Balancing the risks and benefits of moderate drinking. Annals of the New York Academy of Science 957(May): 1–6.

Etchemendy, J. 1983. The doctrine of logic as form. Linguistics and Philosophy 6(3): 319–334.

Fischhoff, B., S. Lichtenstein, P. Slovic, S.L. Derby, and R.L. Keeney. 1981. Acceptable risk. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Fisher, B., J. Dignam, N. Wolmark, et al. 1999. Tamoxifen in treatment of intraductal breast cancer: National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project B-24 randomised controlled trial. The Lancet 353(9169): 1993–2000.

Frank, R.H. 2000. Why is cost–benefit analysis so controversial? The Journal of Legal Studies 29(2): 913–930.

Gallagher, J. 2011. Prostate screening has no benefit. BBC News, April 1. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-12911174.

Institute, G. 1978. Depo: Do the benefits outweigh the risks? International Family Planning Perspectives and Digest 4(2): 65.

Hammond, J.S., R.L. Keeney, and H. Raiffa. 1999. Smart choices: A practical guide to making better life decisions. New York: Broadway Books.

Hansson, S.O. 2005. Seven myths of risk. Risk Management 7(2): 7–17.

Hansson, S.O. 2007. Philosophical problems in cost–benefit analysis. Economics and Philosophy 23(2): 163–183.

Iltis, A.S. 2005. Stopping trials early for commercial reasons: The risk–benefit relationship as a moral compass. Journal of Medical Ethics 31(7): 410–414.

Khaw, K.T. 1998. Hormone replacement therapy again: Risk–benefit relation differs between populations and individuals. British Medical Journal 316(7148): 1842–1844.

Ladimer, I. 1969. Risk and benefit in human research. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 164(December): 793–801.

Mooney, G.H. 1980. Cost–benefit analysis and medical ethics. Journal of Medical Ethics 6(4): 177–179.

Orme, M. 1990. Thiazides in the 1990s: The risk:benefit ratio still favours the drug. British Medical Journal 300(6741): 1668–1669.

Petch, M.C. 1990. Dangers of thrombolysis: The benefits of thrombolytic treatment for acute myocardial infarction outweigh the risks. British Medical Journal 300(6723): 483–484.

Pochin, E. 1982. Risk and medical ethics. Journal of Medical Ethics 8(4): 180–184.

Read, S. 1994. Formal and material consequence. Journal of Philosophical Logic 23(3): 247–265.

Roberts, T. 1985. Microbial pathogens in raw pork, chicken, and beef: Benefit estimates for control using irradiation. American Journal of Agricultural Economics 67(5): 957–965.

Scott, P.J. 1988. Anticoagulant drugs in the elderly: The risks usually outweigh the benefits. British Medical Journal 297(6658): 1261–1263.

Sen, A. 2000. The discipline of cost–benefit analysis. The Journal of Legal Studies 29(2): 931–952.

Sieber, S.M., and R.H. Adamson. 1975. Maintenance therapy in myeloma: Risk versus benefit. British Medical Journal 2(5970): 557.

Spielthenner, G. 2008. The logical assessment of practical reasoning. SATS—Nordic Journal of Philosophy 9(1): 91–108.

Spielthenner, G. 2010. Lesser evil reasoning and its pitfalls. Argumentation 24(2): 139–152.

The Economist. 2010. Medical technology: The first commercial retinal implant is about to go on sale. It may be crude, but so were the first cochlear implants, 26 years ago. December 11–17.

Tuomisto, J.T., J. Tuomisto, M. Tainio, et al. 2004. Risk–benefit analysis of eating farmed salmon. Science 305(5683): 476–477.

Weijer, C. 2000. The future of research into rotavirus vaccine: Benefits of vaccine may outweigh risks for children in developing countries. British Medical Journal 321(7260): 525–526.

Wilson, R., and E.A. Crouch. 2001. Risk–benefit analysis, 2nd edition. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Winstanley, P. 1996. Mefloquine: The benefits outweigh the risks. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 42(4): 411–413.

Wodak, A., C. Reinarman, P. Cohen, and C. Drummond. 2002. For and against: Cannabis control: Costs outweigh the benefits. British Medical Journal 324(7329): 105–108.

World Medical Association. 2009. Medical ethics manual, 2nd edition. http://www.wma.net/en/30publications/30ethicsmanual/pdf/ethics_manual_en.pdf.

World Medical Association. 2010. Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. http://www.wma.net/en/30publications/10policies/b3/index.html.

Wu, F. 2004. Explaining public resistance to genetically modified corn: An analysis of the distribution of benefits and risks. Risk Analysis 24(3): 715–726.

Zuppa, A.A., and D. de Luca. 2003. Neonatal outcomes and risk/benefit ratio of induced multiple pregnancies. Journal of Medical Ethics 29(4): 259.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Spielthenner, G. Risk-Benefit Analysis: From a Logical Point of View. Bioethical Inquiry 9, 161–170 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11673-012-9366-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11673-012-9366-y