Abstract

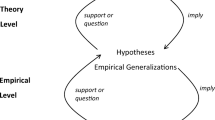

One mainstream approach to philosophy involves trying to learn about philosophically interesting, non-mental phenomena—ethical properties, for example, or causation—by gathering data from human beings. I call this approach “wide tent traditionalism.” It is associated with the use of philosophers’ intuitions as data, the making of deductive arguments from this data, and the gathering of intuitions by eliciting reactions to often quite bizarre thought experiments. These methods have been criticized—I consider experimental philosophy’s call for a move away from the use of philosophers’ intuitions as evidence, and recent suggestions about the use of inductive arguments in philosophy—and these criticisms point out important areas for improvement. However, embracing these reforms in turn gives wide-tent traditionalists strong reasons to maintain other traditional approaches to philosophy. Specifically, traditionalists’ commitment to using intuitions and to gathering them with bizarre thought experiments is well founded, both philosophically and empirically. I end by considering some problems with gathering trustworthy intuitions, and give suggestions about how best to solve them.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Wide-tent traditionalists are also interested in learning truths that go beyond tautologies and contradictions. Because of this, they require data with which to work (although this data may be knowable a priori); they cannot learn what they want about the topics of interest through logic alone. For example, we know about goodness that nothing is both good and not good simultaneously, and we can learn that through logic alone, but we cannot learn anything more substantive without some data about goodness. Thanks to Jonathan Ichikawa for calling my attention to this point.

Each of these philosophers is interested in learning about non-conceptual and non-linguistic things via intuitions: Huemer (2005) believes that intuitions are necessary for learning certain ethical truths, and denies that these truths are determined or constituted by facts about human psychology and concepts; BonJour (1998) grapples with worries about how intuitions are caused by the objects of philosophical scrutiny, a worry that would be relatively trivial if he thought these objects were concepts or word meanings; Bealer’s work talks about concepts a great deal, but close reading of it and discussion with Bealer indicates that he takes these to not be concepts in any psychological sense; examples Weinberg gives as requiring human data (such goodness and rationality) are not areas where the facts are constituted or determined by concepts or meanings.

These can come apart. For example, one might use intuitions as evidence but refuse to use intuitions about bizarre cases, or refuse to use them in deductive arguments. However, we will see they do tend to hang together; later I will argue that if we give up the use of philosophers’ intuitions as data, then we also have more reason to be dubious of deductive arguments based on intuitions.

I’ve borrowed some language from Bealer (1998); while there is a range of fairly nuanced views among philosophers on the matter, there is quite a bit of agreement on these points.

See e.g. Hubner (2012).

There might be cases where an agent reasons to the belief that P and then forgets how they did so. Typically in such cases, their reasoned-to belief is at most as justified after they’ve forgotten how they reasoned to it as it was before. However, the person might assume (perhaps justifiably) that they had a better evidential basis for the belief that P than they actually did, and perhaps this would make their reasoned-to belief that P more justified once they have forgotten how they reasoned to it than it was when they still remembered. I’m not sure if this is correct, but, even if it is, this would not make reasoned-to beliefs the sort of evidence philosophers should want to use when arguing.

If you aren’t fully convinced, consider this kind of thing in a betting context. Say that E is the total evidence about the probability that P (say that it is .999); this evidence warrants betting as if P was .999 likely to be true. Assume that the probability of P is sufficiently high that Fred reasons to the judgment that P. But if that gives him evidence that P, he could now rationally have a credence in P that is higher than .999, and so rationally make bets as if P were more likely than .999. That is bad gambling behavior, and violates Lewis’ Principal Principle (Lewis 1980) (you decide which is worse).

I have also been asked in the past how the argument given in this paragraph fits with Williamson’s claim that E = K, and with worries about bootstrapping. The point I am making here is orthogonal to both issues, I think. Bootstrapping involves using judgments that P as evidence for Q (usually that one is a reliable judge), not for P. Accepting E = K does not, as far as I can tell, require accepting that one’s knowledge that P gives one additional evidence that P beyond whatever that knowledge is based on; if it does, then see my argument above for why I would reject that.

In some cases we will not have in-practice access to the data on which these judgments are based. In such cases, these judgments are evidence, but we should of course be a bit dubious of them.

This does not mean that philosophers have reason to be interested in all intuitions. It may be that intuitions about certain cases are easily swayed by context, or changes in the wording of thought experiments. Such intuitions may not be useful data, although I take no stand on this issue. Even if philosophers should be or are only interested in “stable” or “considered” or “deep” intuitions, each of these is still distinct from reasoned-to judgments.

What about a case where Jacqueline’s feeling is based on unconscious reasoning from an acceptance of deontological principles? If her acceptance of these principles is conscious, then this case would be orthogonal to the views I’m discussing: on the view I’m attributing to BonJour (1998), or that I discuss in my 2009 paper, intuitions are (sometimes) based on information we don’t have intuition-independent access to, and not just acceptance of a view. If the intuition is based on unconscious acceptance of deontological principles, where that acceptance is based on information that we don’t have intuition-independent access to, then the intuition is based on information that is “new” to Jacqueline’s conscious mind, and would give her new evidence.

Although see Williamson (2007) for interesting evidence that philosophers often report what I would call reasoned-to judgments when saying they are reporting intuitions.

The inference to the best explanation approach is, to my mind, a (potentially) more formal version of the reflective equilibrium approach to theory generation. On the reflective equilibrium approach, we take our data (including intuitions), weigh it, and look for a theory that best fits as much of the data as we can. However, we are typically willing to revise at least some of our data, even our intuitions; since intuitions are not under our control, this “revision” is really just not using them in building the final result. This is like inference to the best explanation, since such inferences do their best to generate a result that makes use of all the data, but need not.

Non-fully-independent voting can generate good data as long as there is enough independence. See Ladha (1992).

A more precise and accurate characterization of the problem is beyond what I have space for here, and does not make much difference to the points I am arguing for. For more on independence in voting approaches to theory confirmation, see Goldman (2010), or the literature on Condorcet’s Jury Theorem.

See e.g. Kahneman and Frederick (2002) for such a theory.

What makes a thought experiment bizarre in the appropriate way is a complicated issue. It is clearly relative to time and location; teletransportation might have been bizarre to Americans earlier in the twentieth century, but post Star Trek, it is has been the subject of much social “discussion.” It also depends on whether we are concerned about structural or superficial similarities between a thought experiment and some topic of social “discussion.” Altering superficial aspects of a case might reduce exemplar effects, but not affect the fact that a case resembles in less superficial ways one portrayed on television the night before.

Distracted observers reported the speakers’ actual views (and not those they endorsed in the speech) when asked.

See Bengson (forthcoming), for this concern raised in a somewhat different context (he argues that all experimental philosophy might be gathering guessing).

Intuitions might be swayed by irrelevant factors as well—this is one of the things that experimental philosophers claim to have discovered. One might worry that we cannot detect a difference between results produced by guesses and results produced by unstable intuitions. There is, however, a difference between the irrelevant factors that we should expect to affect guesses and the ones that may have been shown to affect intuitions. Guesses can be very heavily affected by factors that play no evidential role in cognition about the judgment at hand, whereas to date we have only seen that intuitions are affected by factors that we think should not affect them, but that plausibly are either taken as evidence or affect the evidence considered when making the judgment studied. For example, looking at thought experiments in different orders sometimes affects judgments, but this is not a sign that these judgments are guesses, since what happened in one thought experiment could be plausibly seen as relevant to one’s understanding of the next one. The influence of moral factors on judgments of intentionality (e.g. Knobe 2003) is perhaps inappropriate, but it also makes sense that intuitions (and not just guesses) would be so affected, because the blameworthiness of some person described in some thought experiment could be seen as evidence that they must have acted intentionally.

Suggested to me by Michael Huemer. Confidence is correlated with the stability of philosophical judgments (Wright 2010), which at least suggests that it is a sign of not having guessed.

Thanks to Chris Heathwood for this example.

We might find that some level of bizarreness does make it generally difficult for our intuitive faculties to identify the surface or intermediate features of a thought experiment. If so, we should look for the “sweet spot,” so to speak, for thought experiments, where they are novel enough to reduce the effects of communication but familiar enough that subjects can still have reliable intuitions about them.

References

Alter, A. L., Oppenheimer, D. M., Epley, N., & Eyre, R. N. (2007). Overcoming intuition: Metacognitive difficulty activates analytic reasoning. Journal of Experimental Philosophy: General, 136, 569–576.

Bealer, G. (1998). Intuition and the autonomy of philosophy. In M. R. DePaul & W. Ramsey (Eds.), Rethinking intuitions. Lanham, MA: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Begg, I. M., Anas, A., & Farinacci, S. (1992). Dissociation of processes in belief: Source recollection, statement familiarity, and the illusion of truth. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 121, 446–458.

Bengson, J. (forthcoming). Experimental attacks on intuitions and answers. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research.

Betsch, T., Plessner, H., Schwieren, C., & Gutig, R. (2001). I like it but I don’t know why: A value-account approach to implicit attitude formation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27, 242–253.

BonJour, L. (1998). In defense of pure reason. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dijksterhuis, A. (2004). Think different: The merits of unconscious thought in preference development and decision making. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87, 586–598.

Finucane, M. L., Alhakami, A., Slovic, P., & Johnson, S. M. (2000). The affect heuristic in judgments of risks and benefits. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 13, 1–17.

Gilbert, D. T., & Hixon, J. G. (1991). The trouble of thinking: Activation and application of stereotypical beliefs. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60, 509–517.

Gilbert, D. T., & Krull, D. S. (1988). Seeing less and knowing more: The benefits of perceptual ignorance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 193–202.

Goldman, A. (2010) Philosophical naturalism and intuitional methodology. In Proceedings and addresses of the American Philosophical Association.

Greenwald, A. G. (1976). Within-subjects designs: To use or not to use? Psychological Bulletin, 83, 314–320.

Hanson, R. (2002). Why health is not special: Errors in evolved bioethical intuitions. Social Philosophy & Policy, 19, 153–179.

Hubner, B. (2012). Reflection, reflex, and folk intuitions. Consciousness and Cognition, 21, 597–750.

Huemer, M. (2001). Skepticism and the veil of perception. New York: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.

Huemer, M. (2005). Ethical intuitionism. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Kahneman, D., & Frederick, S. (2002). Representativeness revisited: Attribute substitution in intuitive judgment. In T. Gilovich, D. Griffin, & D. Kahneman (Eds.), Heuristics and biases (pp. 49–81). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Knobe, J. (2003). Intentional action in folk psychology: An experimental investigation. Philosophical Psychology, 16, 309–324.

Knobe, J., & Fraser, B. (2008). Causal judgment and moral judgment: Two experiments. In W. Sinnott-Armstrong (Ed.), Moral psychology, volume 2: The cognitive science of morality: Intuition and diversity. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Knobe, J., & Prinz, J. J. (2008). Intuitions about consciousness: Experimental studies. Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences, 7(1), 67–83.

Ladha, K. K. (1992). The Condorcet Jury Theorem, free speech, and correlated votes. American Journal of Political Science, 36, 617–634.

Lewicki, P., Hill, T., & Czyzewska, M. (1992). Nonconscious acquisition of information. American Psychologist, 47, 796–801.

Lewis, D. (1980). A subjectivist’s guide to objective chance. In R. C. Jeffrey (Ed.), Studies in inductive logic and probability. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Murphy, G. L. (2002). The big book of concepts. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Nahmias, E., Morris, S., Nadelhoffer, T., & Turner, J. (2005). Surveying freedom: Folk intuitions about free will and moral responsibility. Philosophical Psychology, 18, 561–584.

Parfit, D. (1984). Reasons and persons. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Smith, E. R. (1992). The role of exemplars in social judgment. In L. L. Martin & A. Tesser (Eds.), The construction of social judgments. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Sytsma, J., & Machery, E. (2010). Two conceptions of subjective experience. Philosophical Studies, 151(2), 299–327.

Talbot, B. (2009). Psychology and the use of intuitions in philosophy. Studia Philosophica Estonica, 2, 157–176.

Weatherson, B. (2003). What good are counterexamples? Philosophical Studies, 115, 1–31.

Weinberg, J. (2010). Humans as instruments, or, the inevitability of experimental philosophy. Manuscript.

Weinberg, J. M., Nichols, S., & Stich, S. (2001). Normativity and epistemic intuitions. Philosophical Topics, 29(1–2), 429–460.

Williamson, T. (2007). The philosophy of philosophy. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Wright, J. C. (2010). On intuitional stability: The clear, the strong, and the paradigmatic. Cognition, 115, 491–503.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Jonathan Weinberg, Julia Staffel, Michael Huemer, Janet Levin, and Chris Heathwood for their help with this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Talbot, B. Reforming intuition pumps: when are the old ways the best?. Philos Stud 165, 315–334 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-012-9949-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-012-9949-9