Abstract

Covert spatial attention alters the way things look. There is strong empirical evidence showing that objects situated at attended locations are described as appearing bigger, closer, if striped, stripier than qualitatively indiscernible counterparts whose locations are unattended. These results cannot be easily explained in terms of which properties of objects are perceived. Nor do they appear to be cases of visual illusions. Ned Block has argued that these results are best accounted for by invoking what he calls ‘mental paint’. In this paper I argue, instead, in favour of an account of these phenomena in terms of the perceptual experience of affordances concerning saccadic eye movement. As part of the argument I draw connections with the empirical literature on the way in which performance efficiency also alters visual appearance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For results concerning spatial frequency and gap size see (Gobell and Carrasco 2005); for colour saturation (Fuller and Carrasco 2006); for motion coherence (Liu et al. 2006); for flicker rate (Montagna and Carrasco 2006); for speed (Turatto et al. 2007); and for size of a moving object (Anton-Erxleben et al. 2007).

In this paper I use the term ‘perception’ to refer to the successful cases of detection of objects and properties by mean of the senses. I shall not presume that all perception is conscious. I shall reserve the term ‘experience’ to conscious states of sensory awareness. Thus, experiences include both conscious perceptions and illusions as well as hallucinations. This is not to say that there are experiences which are common to all of these cases.

By ‘phenomenal character’ I mean what it is that we are aware of when we have the experience. Thus, I do not take phenomenal character to be a property of the experience itself. See Fish (2010, p. 17) for an explanation of these two distinct interpretations of this notion.

These cases also might tempt one to conclude that at least some of these experiences must be illusory. But this conclusion is to be resisted on grounds similar to those mentioned above with regard to attention.

Or at least could be adopted given the considerations offered in this paper. There might however be other features of affordances that support arguments in favour of one of these two families of positions.

Spatial resolution is the ability to detect fine patterns. Attention has been shown to enhance this ability. For an overview see Carrasco (2011, p. 1500).

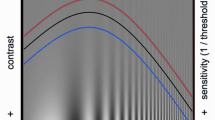

Michelson contrast is defined as the result of subtracting the lowest luminance of the darker areas from the highest luminance of the lighter area divided by the highest luminance plus the lowest luminance. ‘Perceived contrast’ is intended to refer to what it is like to experience a given contrast.

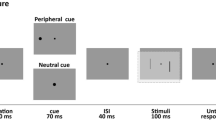

A Gabor patch is a sinusoidal luminance pattern with a fixed contrast (see Figure 2).

For ease of exposition, and following Carrasco’s and Block’s usage, I will sometimes use the expressions ‘attended stimulus’ or ‘attended patch’ as shorthand for ‘attended location at which the stimulus (patch) is situated’. It is important to remember, however, that strictly speaking this paper is exclusively concerned with visual spatial attention; that is to say, visual attention directed at spatial locations.

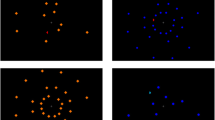

Subsequent experiments have shown the existence of similar effects of covert transient or exogenous attention for other properties such as colour saturation, gap size, flicker rate, speed, motion coherence and size of moving objects (see note 1 for references).

In this paper I do not take a stance about which of these two families of views is correct. Also, below I adopt both Block’s terminology and characterizations for these two families of views. Arguably, his presentation fails to do justice to some of their more sophisticated versions. The account offered here suggests that even the most hard-nosed reductivist versions of representationists have a response to Block’s objections.

Premise 1 could be challenged since Carrasco’s experiments involve force choice snapshot judgements which might be guided by unconscious enhanced sensitivity to contrast in attended regions of space. Block’s defence of premise 2 is based exclusively on the claim that Carrasco’s effects are subject to visual adaptation. Thus, he is able to exclude the possibility that they are a result of cognitive bias. But he cannot establish that they are due to the phenomenology of perception rather than to that of attention. As a matter of fact, some earlier studies on how attention alters appearance explicitly identify the phenomenon as one pertaining to the phenomenology of attention and thus concerning “attensity” (the phenomenal quality of attended objects) rather than to the phenomenology of perception (Prinzmetal et al. 1997). In defence of premise 3 Block contrasts the results of the Carrasco experiments with other cases where he acknowledges that attention gives rise to illusions (Cf., Tse 2005).This is also not dissimilar from the distorting effect of pro-attitudes that make us, for instance, treat desired objects as if they were closer to us than they really are as revealed by both verbal reports and actions toward the objects (Balcetis and Dunning 2010). Nevertheless, I am inclined to concede something akin to premise 3 because attention is not an all or nothing phenomenon. It is a matter of degrees. Thus, when we look we might pay attention to more than one point in space; we might attend to a whole area whilst attending more to some portions of it than to others (Cf. Carrasco 2011, p. 1487). This shows that the boundaries of attention are vague; it might also be the case that the boundaries between illusion and perception are vague insofar as it might be true that there are borderline cases. However, the vagueness of the boundaries of attention present in most cases of perception would mean that almost every case is on the borderline between illusion and perception.

It is worth noting, however, that Carrasco explicitly claims that subjective contrast is tantamount to salience (Carrasco et al. 2004, p. 308).

The view that I defend here differs from Gibson’s in some respects. Importantly, I take objects and their properties to be perceivable as well as affordances. Gibson claimed that only the latter are perceived.

Although Proffitt does not elaborate on the notion of intention deployed here, I shall presume that he is not concerned here with intentions as a distinct kind of mental states that precede and guide intentional actions. Rather I take him to be concerned with a certain kind of activity; namely, intentional action.

I presume that these purposes need not be conscious. Proffitt himself is silent on this issue.

For Proffitt the ability to select actions which are achievable is often learnt. It is only by trial and error that subjects acquire the ability to perceive many of the affordances that surround them (Proffitt 2013, p. 477).

Yet, as Bhalla and Profitt also notice, subjects do not stumble over when they attempt to walk up hills. This fact is taken by Bhalla and Profitt as evidence of the existence of a dual visual system. One system controls visually guided activities such as the fine calibration of the angle of the foot when walking uphill; the other conscious system guides the planning of molar behaviours such as gait selection (Bhalla and Proffitt 1999, pp. 1076–7). For the classic statement of the dual system theory see Milner and Goodale (2006). It should be noted that attention is thought to play a crucial role in how the two systems interact. The exploration of the compatibility between the dual visual system theory and the embodied approach to perception is beyond the scope of this paper.

For a list see Appendix of Proffitt (2013).

A demand characteristic is a bias in experimental design that occurs when what experimenters are trying to predict becomes transparent to the subjects.

This possibility is openly accepted by Woods et al. (2009, p. 1116).

There is a lively philosophical debate about the nature and range of the properties that can figure in the content of perception. This is a matter that I cannot address here. For a defence of the view that high level properties can be represented in perception see Siegel (2010). This issue is also linked in complex ways to discussions about the cognitive penetrability of perception (Cf., Stokes (2013) for an overview of debates on this topic). I shall not take a stance on whether perception must be cognitively penetrable if affordances are perceived. Proponents of the embodied perception approach seem to think that perception is penetrable. Nanay (2011 and 2012) does not discuss this issue.

These considerations may raise the more general worry about the testability of Proffitt’s position. Whilst I cannot fully address the issue here, it would seem at the very least that experimental designs in which the environment does not actually present the subject with the relevant affordances cannot count as offering evidence against it.

Firestone’s other two challenges appear to ignore Proffitt’s point that the perception of affordances is largely learnt over time by trial and error.

Perception is clearly involved in the fine control and guidance required to carry out the activity which has been selected. Proffitt’s point is that perception is not involved in the formation of the intention to act in some way or other.

This, of course, is not to say that such phenomenal changes are sudden or large. Instead, they are generally gradual and often small.

This point is of significance because the premotor theory of covert attention, which I mention below as a possible source of support for my view, has received substantial empirical confirmation as an account of this kind of attention. Carrasco and her team are not supporters of the premotor theory. Instead, Carrasco appears to favour the biased competition model (Carrasco 2011, p. 1486–7). Nevertheless, the premotor theory of attention is not ruled out as incorrect by Rolfs and Carrasco in their 2012 which advances evidence that supports the dissociation of covert attention and saccadic preparation based on the timings of effects of saccadic preparation which were faster than those of either kind of covert attention (2012, p. 13751). The behavioural results discussed here, however, do not offer direct support for any specific theory of the computational or neurological mechanisms underpinning attention. Instead, they highlight some conscious phenomena concerning attention which any theory of attention would need to be able to explain.

Recall that ‘perceived’ in this context is used as broadly equivalent to ‘consciously perceived’ or ‘experienced’.

It should be noted, however, that these considerations cannot be adopted by Block himself who resists the characterisation of the changed experience as one of enhanced salience.

In an earlier version of this paper I had rephrased this phenomenology in terms of the whole patch simply jumping out more against its background. I would like to thank an anonymous referee for this journal for pressing that there is an important difference between effects about edges and effects about foreground/background.

We also experience it as, in some sense, demanding that we direct our eyes toward it. The object captures our attention and we are inclined to move our eyes so that we can take a look at it.

With exception of course of the location on which one’s eyes are currently fixated.

There are two kinds of saccades: intentional or voluntary and preintentional or reflexive. The latter include saccades which are part of an overall pattern of activity that is initiated and controlled by intentions but which are not themselves the result of a specific intention or fully specified by the intention guiding the overall activity (cf., Rowlands 2006, p. 104). In either case there is evidence that saccades to a target cannot take place unless covert spatial attention has first been directed to that location (see, for voluntary saccades, Hoffman and Subramaniam 1995). For a more recent debate on whether there is a correlation between covert attention and microsaccades, see Horowitz et al. (2007a) followed by a commentary by Laubrock et. A. (2007) and a response by Horowitz et al. (2007b).

By ‘enactivism’ I mean a view akin to that advanced by Alva Noë (2004).

I do not mean my comments here to be read as claiming that Carrasco’s results are due to cue bias which she ruled out in a control experiment. In other words, participants do not select the gap that is attended merely because it is attended. What I suggest is that they select the gap that affords gazing more easily.

Or perhaps, more weakly, my argument supports the conditional claim that if we admit affordances among the possible objects of experience, their inclusion makes available a plausible explanation of the phenomena under discussion.

For empirical evidence that in some cases the information is gathered ‘on the fly’ on the basis of the perceiver’s actual movements see Fink et al. (2009).

For a similar characterisation of affordances see Nanay (2012, p. 431).

O’Shaughnessy refers to such movements as deeds or subintentional acts (1980, p. 60). He also argues that these acts are the result of non intentional tryings (1980, p. 96). I follow Rowlands’ choice here of reserving ‘deeds’ for pre-intentional acts (2006, p. 99) and in rejecting the view that sub-intentional acts constitute genuine tryings (2006, p. 102).

Deeds so defined can be completely sub-personally controlled and we might be completely unaware of them. They would still count as “actions” when they have success conditions and are part of an overall activity which is intentional.

I would like to thank an anonymous referee for this journal for pressing this issue.

Prosser (2011) takes properties like being heavy or steep to be affordances. I have claimed that affordances are properties like being liftable or being walkable. However, my view of affordances is related to his in so far as the properties he identifies pertain to the phenomenology of perceiving affordances.

My thanks to one of the referees for this journal for drawing to my attention the need to clarify this issue.

Although Proffitt is not explicit on these issues, I presume that he holds a similar view on this matter.

I claim that Block’s argument has been blocked at 4. Alternatively, as one referee for this journal has suggested, one could claim that scaling might be an alternative to mental paint when explaining how a difference in phenomenology may be due to something other than the objects and properties that are perceived.

Earlier versions of this paper were delivered to workshops at Cardiff University and as a seminar talk to the Philosophy Department at the University of Bristol. I would like to thank audiences at those events and the two anonymous referees for this journal for their constructive comments.

References

Anton-Erxleben, K., Henrich, C., & Treue, S. (2007). ‘Attention changes perceived size of moving visual patterns.’ Journal of Vision, 7 (11), Article 5. Available from http://www.journalofvision.org/7/11/5/.

Balcetis, E., & Dunning, D. (2010). Wishful seeing. Psychological Science, 21(1), 147–52.

Bennett, D. J. (2011). How the world is measured up in size experience. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 83(2), 345–65.

Bhalla, M., & Proffitt, D. R. (1999). Visual-motor recalibration in geographical slant perception. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception & Performance, 25(4), 1076–96.

Block, N. (2010). Attention and mental paint. Philosophical Issues, 20(1), 23–63.

Carrasco, M. (2011). Visual attention: the past 25 years. Vision Research, 51(13), 1484–525.

Carrasco, M., Ling, S., & Read, S. (2004). Attention alters appearance. Nature Neuroscience, 7, 308–313.

Durgin, F. H., Baird, J. A., Greenburg, M., Russell, R., Shaughnessy, K., & Waymouth, S. (2009). Who is being deceived? The experimental demands of wearing a backpack. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 16, 964–969.

Fink, P. W., Foo, P. S., & Warren, W. H. (2009). Catching fly balls in virtual reality: a critical test of the outfielder problem. Journal of Vision, 9(13), 1–8.

Firestone, C. (2013). How “paternalistic” is spatial perception? Why wearing a heavy backpack doesn’t—and couldn’t—make hills look steeper. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 8(4), 455–73.

Fish, W. (2010). Philosophy of perception: A contemporary introduction, routledge contemporary introductions to philosophy. London and New York: Routledge.

Fuller, S., & Carrasco, M. (2006). Exogenous attention and color perception: performance and appearance of saturation and hue. Vision Research, 46, 4032–47.

Gibson, J. J. (1986). The ecological approach to visual perception. Hillsdale, N.J. and London: Erlbaum.

Gobell, J., & Carrasco, M. (2005). Attention alters the appearance of spatial frequency and gap size. Psychological Science, 16, 644–51.

Harman, G. (1990). The intrinsic quality of experience. Philosophical Perspectives, 4, 31–52.

Hoffman, J. E., & Subramaniam, B. (1995). The role of visual-attention in saccadic eye-movements. Perception & Psychophysics, 57(6), 787–795.

Horowitz, T., Fine, E., Fencsik, D., Yurgenson, S., & Wolfe, J. (2007a). Fixational eye movements are not an index of covert attention. Psychological Science, 18(4), 356–63.

Horowitz, T., Fencsik, D., Fine, E., Yurgenson, S., & Wolfe, J. (2007b). Microsaccades and attention: does a weak correlation make an index? Reply to Laubrock, Engbert, Rolfs, and Kliegl (2007). Psychological Science, 18(4), 367–68.

Laubrock, J., Engbert, R., Rolfs, M., & Kliegl, R. (2007). Microsaccades are an index of covert attention: commentary on Horowitz, Fine, Fencsik, Yurgenson, and Wolfe (2007). Psychological Science, 18(4), 364–66.

Liu, T., Fuller, S., & Carrasco, M. (2006). Attention alters the appearance of motion coherence. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 13, 1091–96.

Liu, T., Abrams, J., & Carrasco, M. (2009). Voluntary attention enhances contrast appearance. Psychological Science, 20, 354–362.

Loomis, J. M., & Philbeck, J. W. (2008). Measuring perception with spatial updating and action. In R. L. Klatzky, M. Behrmann, & B. MacWhinney (Eds.), Embodiment, ego-space, and action (pp. 1–42). New York: Psychology Press.

Milner, A. D., & Goodale, M. A. (2006). The visual brain in action (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Montagna, B., & Carrasco, M. (2006). ‘Transient covert attention and the perceived rate of flicker’. Journal of Vision, 6(9), Article 8. Available from http://www.journalofvision.org/6/9/8/.

Nanay, B. (2011). Do we see apples as edible? Pacific Philosophical Quarterly, 92(3), 305–22.

Nanay, B. (2012). Action-oriented perception. European Journal of Philosophy, 20(3), 430–46.

Noë, A. (2004). Action in perception. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

O’Shaughnessy, B. (1980). The will (Vol. 2). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Porritt, A. (1987). Ghost-writer to W.G. Grace. In M. Davie & S. Davie (Eds.), The faber book of cricket (pp. 119–122). London: Faber and Faber.

Prinzmetal, W., Nwachuku, I., Bodanski, L., Blumenfeld, L., & Shimizu, N. (1997). The phenomenology of attention 2. Brightness and contrast. Consciousness and Cognition, 6(2/3), 372–412.

Proffitt, D. R. (2008). An action-specific approach to spatial perception. In R. L. Klatzky, B. MacWhinney, & M. Behrmann (Eds.), Embodiment, ego-space, and action (pp. 179–202). New York: Psychology Press.

Proffitt, D. R. (2013). An embodied approach to perception: by what units are visual perceptions scaled? Perspectives on Psychological Science, 8(4), 474–83.

Proffitt, D. R., & Linkenauger, S. A. (2013). Perception viewed as a phenotypic expression. In W. Prinz, M. Beisert, & A. Herwig (Eds.), Action science: Foundations of an emerging discipline (pp. 171–98). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Proffitt, D. R., Bhalla, M., Gossweiler, R., & Midgett, J. (1995). Perceiving geographical slant. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 2(4), 409–28.

Proffitt, D. R., Stefanucci, J., Banton, T., & Epstein, W. (2003). The role of effort in perceiving distance. Psychological Science, 14(2), 106–12.

Prosser, S. (2011). Affordances and phenomenal character in spatial perception. Philosophical Review, 120(4), 475–513.

Rizzolatti, G., & Craighero, L. (1998). Spatial attention: Mechanisms and theories. In M. Sabourin, F. Craik, & M. Robert (Eds.), Advances in psychological science, Vol. 2: Biological and cognitive aspects (pp. 171–98). Hove: Psychology Press/Erlbaum.

Rizzolatti, G., Riggio, L., Dascola, I., & Umiltá, C. (1987). Reorienting Attention across the Horizontal and Vertical Meridians: Evidence in Favor of a Premotor Theory of Attention. Neuropsychologia, 25(1, Part 1), 31–40.

Rolfs, M., & Carrasco, M. (2012). Rapid simultaneous enhancement of visual sensitivity and perceived contrast during saccade preparation. The Journal of Neuroscience, 32(40), 13744–52.

Rowlands, M. (2006). Body language: Representation in action. Cambridge and London: MIT Press.

Siegel, S. (2010). The contents of visual experience. New York: Oxford University Press.

Smith, D. T., & Schenk, T. (2012). The premotor theory of attention: time to move on? Neuropsychologia, 50(6), 1104–14.

Stokes, D. (2013). Cognitive penetrability of perception. Philosophy Compass, 8(7), 646–63.

Styles, E. A. (2006). The psychology of attention. Hove: Psychology Press.

Tse, P. U. (2005). Voluntary attention modulates the brightness of overlapping transparent surfaces. Vision Research, 45, 1095–1098.

Turatto, M., Vescovi, M., & Valsecchi, M. (2007). Attention makes moving objects be perceived to move faster. Vision Research, 47, 166–78.

Witt, J. K., & Proffitt, D. R. (2005). See the ball, hit the ball. Psychological Science, 16, 937–938.

Witt, J. K., & Proffitt, D. R. (2008). Action-specific influences on distance perception: a role for motor simulation. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception & Performance, 34(6), 1479–92.

Witt, J. K., Proffitt, D. R., & Epstein, W. (2005). Tool use affects perceived distance, but only when you intend to use it. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception & Performance, 31, 880–888.

Woods, A. J., Philbeck, J. W., & Danoff, J. V. (2009). The various perceptions of distance: an alternative view of how effort affects distance judgments. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception & Performance, 35(4), 1104–17.

Wraga, M. (1999). The role of eye height in perceiving affordances and object dimensions. Perception & Psychophysics, 61(3), 490–507.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tanesini, A. Spatial attention and perception: seeing without paint. Phenom Cogn Sci 14, 433–454 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11097-014-9349-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11097-014-9349-z