Abstract

Online gambling companies claim that they are ethical providers. They seem committed to corporate social responsibility (CSR) practices that are aimed at preventing or minimising the harm associated with their activities. Our empirical research employed a sample of 209 university student online gamblers, who took part in an online survey. Our findings suggest that the extent of online problem gambling is substantial and that it adversely impacts on the gambler’s mental and physical health, social relationships and academic performance. Online problem gambling seems to be related to the time spent on the Internet and gambling online, parental/peer gambling and binge drinking. As our findings show that there are harmful repercussions associated with online gambling, we argue that companies in this controversial sector cannot reach the higher level of CSR achieved by other industries. Nevertheless, they can gain legitimacy on the basis of their CSR engagement at a transactional level, and so, by meeting their legal and ethical commitments and behaving with transparency and fairness, the integrity of the company can be ensured. We also argue that current failures in the implementation and control of CSR policies, the reliance on revenue from problem gamblers’ losses, and controversial marketing activities appear to constitute the main obstacles in the prevention or minimisation of harm related to online gambling. As online gambling companies must be responsible for the harm related to their activities, we suggest that CSR policies should be fully implemented, monitored and clearly reported; all forms of advertising should be reduced substantially; and unfair or misleading promotional techniques should be banned. The industry should not rely on revenue from problem gamblers, nor should their behaviour be reinforced by marketing activities (i.e. rewards). We realise, however, that it is unrealistic to expect the online gambling industry to prioritise harm prevention over revenue maximisation. Policy makers and regulators, therefore, would need to become involved if the actions suggested above are to be undertaken. CSR is paramount to minimise harm and provide a healthier user experience in this business sector, but it also poses marketing dilemmas. We support a global collaborative approach for the online gambling industry, as harm related to gambling is a public health issue.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Gambling has received increasing social acceptance around the world. The gambling industry is huge and extremely profitable; it is linked with political and economic institutions of the state, promoted as legitimate and practised by the majority of the population (Reith 2007). With the expansion of the Internet, online gambling has emerged as a popular form of entertainment, and it has seen an explosive rate of growth during the last decade. In 2009, there were around 2,500 worldwide online gambling sites owned by 600 organisations (Remote Gambling Association 2010). However, there is a growing concern that this type of activity may introduce significant potential for harm to some individuals and society (Griffiths 2003; Griffiths et al. 2006; LaBrie et al. 2007; McBride and Derevensky 2009; Monaghan 2009; Petry 2006; Smith and Rupp 2005). Current legislation may be insufficient or ineffective in protecting problem gamblers and others who might be at risk, e.g., minors, young adults/university students (Matthews et al. 2009; Monaghan 2009; Schoen et al. 2007; Smith and Rupp 2005). For this reason, some academics have called for an absolute ban on the use of online gambling websites (Smith and Rupp 2005), while others consider that online gambling should be subject to more regulation (Monaghan 2009; Smeaton and Griffiths 2004; Wood and Williams 2007; Williams et al. 2007). Monaghan (2009) argues that banning online gambling may be ineffective in light of previous attempts made in the US and China. Instead, she considers that the activity should be regulated to provide a safer environment and to protect consumers from unscrupulous operators, which in turn will provide tax revenue. However, some warn that although the revenue is attractive to governments, the long-term social cost of the activity might not offset the financial gains (Smith and Rupp 2005; William and Wood 2004).

The Gambling Act 2005 was introduced in the UK to modernise gambling regulations and to govern different forms of gambling, including online gambling. The new legislation was fully implemented by 2007, and it brought both increased responsibilities and freedom to online gambling companies. On the one hand, the act required the implementation of CSR policies as a condition of the licence; on the other hand, it introduced a less-regulated environment, which has resulted in a proliferation of marketing activities (Gordon and Moodie 2009). Clearly, the CSR policies introduced in the Gambling Act 2005 acknowledged the potential harm of gambling and sought to protect public interest, while allowing gambling companies to develop in the marketplace. This two-fold purpose comes from the basic idea of the CSR concept, as Carroll (1999, p. 292) observes: ‘at its core, it [CSR] addresses and captures the most important concerns of the public regarding business and society relationships’. Previous studies have drawn attention to these societal concerns. Monaghan (2009, p. 1) recommends revision because ‘online gambling is not just a fad, but it is here to stay’ and, therefore, given ‘the seriousness of potential associated problems, current regulations must be revised and a moratorium on further expansion recommended allowing harm-minimisation strategies to be introduced’. Smith and Rupp (2005, p. 85) observe that although ‘the online gambling industry offers a superior Internet-based customer service with outstanding interfaces and a variety of games and promotional activities…people in general see the industry as a global problem and a moral hazard’.

The online gambling phenomenon raises a number of questions regarding the moral implications associated with it and the marketing activities it employs. The main aim of this article is to find out the extent and the impact of the harm associated with online gambling, and the implications this has for the role of online gambling companies in addressing problem gambling and maintaining socially responsible behaviour. The study fills a gap in the literature as very little research focuses on CSR in the online gambling industry and online problem gambling.

Literature Review

CSR and the Online Gambling Industry

Broadly defined, CSR refers to a company’s ‘status and activities with respect to its perceived societal or, at least, stakeholder obligations’ (Brown and Dacin 1997). In other words, CSR is what the public expects of businesses. One of the most popular frameworks of CSR is Carroll’s (1991, 1999) CSR pyramidal framework (Crane and Matten 2004), which describes different levels of social responsibility depicted in a pyramid shape. Starting from the bottom, businesses are expected to: (1) be profitable; (2) obey the law; (3) be ethical- do what is right, just and fair, i.e. avoid harm; and (4) be good corporate citizens, i.e. contribute resources to the community and improve quality of life. Carroll (1991, p. 42) acknowledges that these different expectations are ‘in a constant tension with one another’. With his CSR framework, Carroll (2000, p. 35) sought to reconcile the idea that businesses could focus either on profits or social concerns, but not both; he argued that ‘businesses cannot only be profitable and ethical, but that they should fulfil these obligations simultaneously’. This argument is portrayed in his classification of managerial ethics, which distinguishes between moral managers, who are motivated by sound ethical standards and assume ethical leadership, and immoral/amoral managers.

Similar to Carroll’s framework, Palazzo and Richter (2005) propose three levels of CSR. The instrumental level, which refers to a corporation’s ability to deliver products and services with the quality expected by customers, corresponds with Carroll’s first dimension. The transactional level, which refers to a corporation’s integrity, i.e. it complies with legal and moral rules and behaves with transparency and fairness, corresponds with Carroll’s second and third dimensions. Finally, the transformational level, which refers to a corporation’s benevolence, i.e. it goes beyond its self-interest for the common good and contributes to society’s well-being, corresponds with Carroll’s fourth dimension.

Palazzo and Richter’s (2005) CSR framework has been used in the context of the tobacco industry, and thus is useful to answer the fundamental question posed by this article: Can the online gambling industry be socially responsible if its products harm consumers? We endeavoured to examine the three levels of Palazzo and Richter’s (2005) framework in the context of the UK’s online gambling industry. At the instrumental level, it seems clear that this industry offers superior quality services (Griffiths 2003; Smith and Rupp 2005), but it is less clear how this industry can attain higher levels of CSR. At the transactional level of CSR, the industry is expected to comply with legal and moral rules and behave with transparency and fairness, thus avoiding harm or taking responsibility for it, if caused. Is the industry meeting these expectations?

The online gambling market comprises different products: sports betting, poker, casino games, bingo and lottery (KPMG International 2010). According to H2 Gambling Capital (2011), it is predicted that the worldwide market for online gambling will grow from US $21.2 bn in 2008 to $36.5 bn in 2012. This is a phenomenal growth of 72 %, especially when compared to the 15 % increase expected for the worldwide gambling market (which includes online gambling) from US $335 bn in 2009 to $385 bn in 2012. Licensed gambling in the UK, estimated at US $10.1 bn in 2012 (H2 Gambling Capital 2011), represents nearly one third (28 %) of the worldwide online gambling market. Online gambling is a very profitable business amidst the economic recession in the UK and elsewhere. Ralph Topping, the Chief Executive of William Hill, Britain’s biggest bookmaker, stated that the company has had a good performance, with online gambling revenue rising nearly one-third (28 %) in the third quarter of 2011, in contrast to a 3 % decline at its retail business (Scuffman and Davey 2011).

According to the Gambling Act 2005, online gambling companies are required to comply with CSR codes of practice to obtain their licence and operate in the marketplace. These companies should ensure that: (1) gambling is conducted in a fair and open way; (2) children and other vulnerable people are protected from being harmed or exploited by gambling; and (3) assistance is made available to people who are, or may be, affected by problems related to gambling (Gambling Commission 2012). In order to demonstrate their commitment to these codes of practice, online gambling companies must obtain the GamCare certification. GamCare is a charity, funded by donations from the British gambling industry within a framework determined by the Gambling Commission, to support gambling research, education and treatment, and to provide information to players on responsible gambling and sources of help for problem gambling. GamCare (2007) aims to ensure that consumers understand the risks and that operators take steps to minimise the likelihood of harm. Some of the CSR policies applied by online gambling companies include: age verification, deposit limits, self-exclusion facilities, ‘free-play’ controls and CSR reporting.

Another key feature of the gambling act is that it regulates online gambling where the operator is located, i.e. the UK. However, according to John Penrose, the Minister responsible for gambling policy and regulation, this approach does not work and he is envisaging changes to the UK legislation. He suggested that online gambling should be regulated at the point of consumption to ensure that overseas operators would not have an unfair advantage over UK-based companies and that consumers were protected no matter where the operator was based (Department for Culture, Media and Sports 2011). Due to increasing concerns that millions are becoming addicted to online gambling, the UK government is planning to stop overseas advertising and ban the use of credit cards (Gambling News 2011). In America, many companies have already banned the use of their credit cards for online gambling, since, for them, this activity has a great potential for fraud and financial losses (Smith and Rupp 2005).

Concerns Over Online Gambling Activities

During the last decade, home-based gambling (via the Internet, telephone, interactive television or mobile phone) has become increasingly popular, fuelled by new technologies, e.g. tablets, laptops, netbooks and smartphones. In addition to the immersive nature of the Internet and the ability to use electronic payments, online gambling offers many benefits to its users, including: a higher degree of privacy and anonymity, greater access, 24/7 availability, convenience and ease, solitary play, and attractive and exciting video-game features (Griffiths 2003; Smith and Rupp 2005). A negative aspect is that it allows players to gamble under a greater influence of drugs or alcohol than allowed in a public venue (Griffiths and Parke 2002; McBride and Derevensky 2009). It is not surprising, therefore, that there has been a growing concern that technological developments in online gambling may increase problem gambling (Griffiths and Parke 2002) and that individuals with an existing gambling problem may be particularly attracted to this form of gambling (Wood et al. 2007). Griffiths et al. (2006, p. 37) warn against the potential increase in the number of online problem gamblers or ‘gambling addicts’ because the technology lends itself to excessive gambling, due to its accessibility and the frequency of play. They argue that ′games that offer a fast, arousing span of play, frequent wins and the opportunity for rapid replay are associated with problem gambling’.

Recently, online gambling in the UK has received significant attention. The latest British Gambling Prevalence Survey 2010 reports that an estimated 0.9 % of people aged 16 and over can be classed as problem gamblers, a substantial increase of 50 %, from the 0.6 % recorded in both 2007 and 1999 (Wardle et al. 2011, p. 11). An upsurge in problem gambling had been predicted in previous studies as a consequence of the relaxation of gambling rules (Moodie 2008; Gordon and Moodie 2009; Griffiths 2003). Problem gambling was found to be highest among those taking part in poker at the pub/club (12.8 %), followed by new forms of gambling, i.e. online slot-machine style games (9.1 %) and fixed-odds betting terminals (8.8 %) (Wardle et al. 2011, p. 94).

Online problem gambling can be defined as an addiction to gambling via the Internet. Goodman (1990, p. 1404) defines addiction as:

A process whereby a behaviour, that can function both to produce pleasure and to provide escape from internal discomfort, is employed in a pattern characterized by (1) recurrent failure to control the behaviour (powerlessness) and (2) continuation of the behaviour despite significant negative consequences (unmanageability).

Griffiths et al. (2006) emphasise that, although it has been acknowledged that addiction results from a combination of different elements, including an individual’s genetic and psycho-social factors, in the case of online gambling, the technology itself can be a determinant factor in the development of addictive behaviour.

Consequently, online problem gambling may be associated with concerns well recognised in offline problem gamblers, which include harm to their social relationships, employment, mental and physical health, and financial situation (Ladouceur et al. 1994; Sanders and Peters 2009; Shaw et al. 2007). However, there is little empirical research on the impact of online gambling on gamblers’ lives or on the way that the activity could develop into a problem for some individuals. Problem gambling (sometimes referred to as ‘pathological’, ‘compulsive’, ‘disordered’ or ‘excessive’) ‘is characterised by difficulties in limiting money and/or time spent on gambling, which leads to adverse consequences for the gambler, others, or for the community’ (Australasian Gaming Council 2008, p. 1). Volberg et al. (2006, p. 4) state that gambling problems exist on a continuum and vary in severity and duration, with pathological gambling at the most severe end of this continuum. They define pathological gambling as ‘a treatable mental disorder characterized by loss of control over gambling, chasing of losses, lies and deception, family and job disruption, financial bailouts and illegal acts’.

Problem gambling can affect anyone regardless of age, gender, race or social status. Afifi et al. (2010, p. 399) studied the socio-demographic characteristics associated with problem gambling and found no differences between men and women, except that women are ‘more likely to gamble as a means of forgetting about problems or dealing with depressed feelings’. However, most studies have shown that more men than women are affected by problem gambling (Griffiths and Barnes 2008; Moodie 2008; Sproston et al. 2000; Wood and Williams 2007). Problem gambling seems to start at a young age, and it not only affects the gambler but also has far-reaching effects on society. The Australian Medical Association (AMA) (2001) states on its website:

Anyone who gambles can develop a problem. The vast majority of ‘problem gamblers’ start gambling before the age of 20 years, some as early as 8 to 12 years of age. Problem gambling does not just affect the gambler; it also affects family members, friends and others around them. On average, it is estimated that one problem gambler affects 8 other people.

The AMA is aware that gambling is more socially acceptable and is common among young people, but that for some, it can get out of control and take over their lives. On its website AMA (2001) highlights the effects of problem gambling:

Loss of control, resulting in guilt and desperation, which can lead to thoughts of self-harm; stress and worry that affects sleep, mood and health; loss of friends who have lent the gambler money; relationship conflicts including divorce; failed exams; job loss; isolation from family, friends and workmates.

Despite the severe harm associated with gambling, Reith (2007, p. 41) warns that in today’s consumer society, problem gambling is merely seen as an issue of ‘inappropriate consumption’, but this perception might soon change as a result of recent developments. Previous empirical research has shown a strong relationship between online gambling and problem gambling with a substantial proportion (between 30 and 66 %) of respondents classified as problem gamblers (Matthews et al. 2009; McBride and Derevensky 2009; Petry 2006; Wood and Williams 2007). Problem gambling was found to be four times higher in online gamblers compared with offline gamblers (Ladd and Petry 2002; Wood and Williams 2009). Petry (2006) found that online gamblers, in general, suffered from poor mental and physical health. Online problem gamblers were also shown to experience negative moods, including anger, disgust, scorn, guilt, fear and depression, which suggests that these individuals used online gambling as a coping strategy to alleviate these negative moods (Matthews et al. 2009). Wood et al. (2007) examined students who played online poker and found that nearly 20 % were problem gamblers; they played to escape from problems and experienced negative moods after playing. Also, a number of studies have established an association between problem gambling and parental gambling (e.g. Fisher 1993; Lesieur and Klein 1987; Lesieur et al. 1991; Winters et al. 1993). In their comprehensive study in Canada, Wood and Williams (2009, p. 10) found that the most important predictors of online problem gambling were: gambling on different formats, higher expenditures, mental health problems, parental gambling, lower income, negative attitudes about gambling, Asian ethnicity and having other addictions.

Studies have shown that other problematic behaviour, such as binge drinking and cigarette smoking are associated with online problem gambling (Griffiths et al. 2010b; McBride and Derevensky 2009; Volberg et al. 2006). However, there is no indication that online problem gambling is associated with addiction to the Internet itself (Griffiths 2003). McBride and Derevensky’s (2009) study showed that online problem gamblers tend to consume alcohol or illicit drugs while playing, which could affect their decision-making and so render them even more vulnerable. The authors warn about the ‘difficult and disturbing relationship between the Internet and individuals with gambling problems’ (McBride and Derevensky 2009, p. 162) as problem gamblers were more likely to gamble online because they could hide their gambling from others. McBride and Derevensky (2009) concluded that online gambling sites did not provide problem gamblers with the same protection as offline gambling venues and they stressed the importance for online gambling sites to have CSR policies in place to help those with gambling problems. Despite the contribution of preceding studies, online gambling is a relatively new activity and empirical research remains scarce, so little is known about the psycho-social characteristics of online gamblers, or the impact the activity may have on their lives. Moreover, there has been little discussion of the role that online gambling organisations play in addressing online problem gambling and whether they are able to maintain socially responsible behaviour.

Can Online Gambling Companies Gain Legitimacy from CSR Practices?

There seems to be a general consensus that a company needs to recognise that it is a part of society, and that this entails responsibilities which are much broader than profit-making (Dawkins and Lewis 2003). Therefore, it is imperative for organisations to define the role they have in the wider society and embrace ethical, legal and responsible standards (Lindgreen and Swaen 2004; Lindgreen et al. 2009); otherwise, organisations can lose their perceived legitimacy (Campbell 2007). This is important because organisations with questionable legitimacy would experience diminished public support and less positive views from the media (Marcus and Goodman 1991) and ultimately would be seen as less meaningful and trustworthy (Suchman 1995).

Controversial or sin industries have been described as those which are related to ‘products, services or concepts that for reasons of delicacy, decency, morality, or even fear, elicit reactions of distaste, disgust, offence or outrage when mentioned or when openly presented’ (Wilson and West 1981, p. 92). Because little research has been conducted on CSR in controversial industries, the understanding of how companies in these sectors could gain legitimacy through CSR activities is limited. Laczniak and Murphy (2007) stressed that these firms have unique ethical obligations as a result of the negative impact that their activities may have on some consumers. A study by Hong and Kacperczyk (2009) found that the stocks of companies in the gambling, tobacco and alcohol industries had higher associated risk and returns, because of the social norms against investing in these companies. Cai et al. (2011), however, found a positive relationship between CSR practices and firm value in controversial industries. They concluded that, on average, companies in these sectors were managed morally or strategically and could be socially responsible, despite the harm their products might cause to their environment, human beings and society.

Today, it is acknowledged that the development and implementation of CSR initiatives constitutes a win–win situation for both the organisation and its environment (Lindgreen et al. 2008) as they have a positive influence on a wide range of stakeholders, including consumers, employees and investors (Dawkins and Lewis 2003). There is also evidence that a bad social performance damages a company’s financial performance (Margolis and Walsh 2003). Bhattacharya and Sen (2004) found that consumers reacted negatively to companies ‘doing bad’ or not practising CSR, and such companies run the risk of being perceived as socially irresponsible. However, they also found that consumers showed increased loyalty and positive word-of-mouth towards companies who were perceived to be practising CSR. This finding is supported in the online gambling context, as Griffiths et al. (2009) found very high levels of customer loyalty towards a Swedish gambling company using PlayScan (a CSR tool that this company devised to help users to be more responsible in their playing); two-thirds of users played exclusively with the firm. Griffiths (2010a, p. 32) argues that ‘successful online gaming affiliates need to establish and develop user loyalty and affinity’ as gamblers want to play with companies whom they can trust. Griffiths (2010b, p. 36) also emphasises the role of trust in determining online gambling preference: ‘trust is of paramount importance in e-commerce…without trust, the spending of money online is unlikely’. However, customer trust in gambling may be defined more by the perception that the games are fair and invulnerable to cheating rather than by the perception that they do not cause or facilitate harm.

Nevertheless, the high levels of customer loyalty found by Griffiths et al. (2009) appear to demonstrate that customers also perceived the Swedish gambling company to be doing what was right through its CSR practices. In this sense, this particular company seems to enjoy legitimacy, given that ‘CSR normally aims at legitimizing a corporation’s activities and increasing corporate acceptance’ (Palazzo and Richter 2005, p. 390). Therefore, it can be argued that it is possible for online gambling companies to be perceived as ethical, and thus meet the criteria of the transactional level in Palazzo and Richter’s framework.

Because of the dearth in research on CSR in online gambling, little is known about either the implementation of these policies or their effectiveness in protecting consumers. Smeaton and Griffiths (2004) examined the implementation of CSR features in online gambling and found serious failures, such as poor age verification checks, which allowed minors to gamble. In their study of the Swedish gambling company using PlayScan, Griffiths et al. (2009) reported that just over one in four players had used the system, and over half of these found it useful. Wood and Williams (2009) found that players were not enthusiastic about having CSR features automatically applied to them. These studies provide an indication of the low effectiveness of CSR policies in protecting consumers. Paradoxically, the same CSR policies designed to protect consumers seem instead to be promoting the business of online gambling companies. Although the implementation of CSR policies by gambling companies may have a positive impact on consumers’ perception, it would be difficult to claim that the likelihood of harm to consumers has been minimised or avoided by them, considering that problem gambling has increased (Wardle et al. 2011).

Issues Between CSR and the Online Gambling Industry

In Europe, the online gambling industry’s efforts towards engaging in CSR activities are reflected by the European Gaming and Amusement Industry’s (Euromat) position, which insists that CSR programmes have become a systematic norm for gambling operators. However, despite the industry’s apparent commitment to provide a safe environment for consumers, gambling can still harm some individuals. The Church of England (2006) warns against the harmful potential of gambling and its consequences on health and family. Similarly, the British Medical Association (BMA) emphasises that problem gambling can cause physical and mental health problems and it can also exacerbate related conditions including depression, alcoholism and other compulsive behaviour (BMA 2007). In response to problem gambling, Euromat (2007, p. 3) proposed four principles for their CSR strategy: effective research, effective education and communication, regulation, and treatment of pathological gambling. It acknowledges that:

Compulsive gambling, underage gambling and protection of the vulnerable, including children, are serious issues… and while a degree of accountability does fall upon the industry, governments who enjoy substantial revenue from gambling activities every year cannot demur if called upon to play their part.

Euromat suggests that if harm is to be prevented, it is necessary for the government to recognise clearly its responsibility. Euromat claims that it contributes heavily to funding research in the area and that it also provides a number of regulatory and self-regulatory measures to protect consumers (e.g. helplines and information on the risks of excessive gambling, regulation of promotions, self-evaluation tools, self-exclusion and age restrictions). However, it is important to ask to what extent is Euromat’s CSR strategy effective in avoiding or minimising harm associated with problem gambling? Some argue that the simple provision of information by the industry, so that consumers make informed decisions, does little to prevent problem gambling (Williams et al. 2007). Euromat’s responsibility in the treatment of pathological gambling is unclear, as although it constitutes one of its four CSR strategies, the organisation considers that each country’s health system is responsible for the provision of treatment to those who have gambling problems (Euromat 2007). A similar view is held by Griffiths (2010c, p. 89) as he affirms that ‘it is not the gaming industry’s responsibility to treat gamblers but it is their responsibility to provide referral for problem gamblers to specialist third party helping agencies’. He suggests that it is better for the industry to refer their problem customers to online help, such as GamAid, which offers a high degree of anonymity, as this is preferred by these gamblers. However, Wood and Williams (2009) found that over 70 % of Canadian and international online gamblers felt more comfortable with face-to-face counselling rather than online services. This is an important finding for online gambling companies to take on board, as it seems that it is not taken into consideration in their current CSR practices.

In the UK, an important barrier to the provision of help for problem gamblers is the lack of options for treatment and the poor organisation of available services (Gordon and Moodie 2009). In addition, gamblers seem to be unaware of existing treatment options (Moodie 2008). Especially troublesome is the claim made by Gordon and Moodie (2009, p. 250) that, in spite of the huge amounts of income derived from gambling taxation, ‘in the UK none of this money is earmarked for preventing or minimising gambling harms’. Hancock et al. (2008) argue that today governments are expected to adopt more proactive consumer protection strategies as new systems, such as loyalty data, can be used by gambling companies to identify problem gamblers and associated risks for protective interventions. Clearly, the government has the responsibility to protect the public from harm (as in the case of tobacco and alcohol) and it should demand more accountability from the industry. Hancock et al. (2008, p. 67) highlight the vital role of CSR by stating that ‘the business and the ethical case for CSR are now well established’, but that it is necessary to ensure that CSR is ‘driven from the top, by strong corporate leadership’. However, even though controversial industries may attain legitimacy through CSR policies, how can they claim to be socially responsible if their products can cause harm? Also, can these industries claim that they are ethical or good corporate citizens?

Palazzo and Richter (2005) show that the use of CSR in controversial industries is limited as their products are harmful. Other industries can achieve societal legitimacy from four key elements, but these are ineffective or even counterproductive in the case of controversial industries. The first is corporate philanthropy. Online gambling companies donate to charities such as GamCare to fund research and education related to gambling. However, this is a requirement of their licence and so does not necessarily represent true altruism. Giving money to other charities may be controversial, because a large amount of the companies’ revenue comes from problem gamblers. The second element of CSR is stakeholder collaboration. Providing research funding to third parties, for example, to support academic research, is also very controversial, as the objectivity of the findings might be compromised. The third element is CSR reporting. This aspect is fundamental for the online gambling industry as reporting must be radically transparent; this includes acknowledging failures in complying with CSR policies, which they do not seem to be doing at present. The final element is self-regulation, which has been ineffective in other industries. Palazzo and Richter (2005, p. 392) assert that ‘corporate self-regulation often lacks transparency, accountability, and thus is deprived of any legitimacy’. Jones et al. (2007) found that most major gambling companies in the UK publicly report on their CSR commitments, although there are significant variations in the breadth of this reporting among the companies, and there is no evidence that they use CSR performance indicators to assess the effectiveness of these practices. The lack of external control and empirical evidence that validates the usefulness of self-regulatory practices constitutes a major barrier in the advancement of CSR in online gambling (Monaghan 2009).

Consequently, we can conclude that online gambling companies cannot currently claim that they are ethical or good corporate citizens. However, this does not mean they can neglect their CSR, but that their commitment to it should be based on the integrity of the company, which stems from transparent operations. This poses some significant marketing dilemmas.

Marketing Dilemmas and CSR Challenges

The marketing activities of online gambling companies are a major concern. Griffiths (2005, p. 21) argues that advertisements for the promotion of gambling ‘should perhaps be placed in the same category as alcohol and tobacco promotions because of the potentially addictive nature of gambling and the potential for being a major health problem’. Blaszczynski et al. (2004, p. 316) show their concern with the marketing activities of online gambling companies by highlighting that ‘reviewing and setting standards for advertising, signage, inducements to gamble, and monitoring compliance with ethical standards of practice and regulatory commercial requirements’ is a key priority. A parallel can be drawn with other controversial industries. Palazzo et al. (2005, p. 398) state that tobacco companies ‘might consider to substantially reduce marketing activities in general even if the competitors do not follow’, because their marketing activities, though seemingly targeting competitors’ consumers, cannot avoid attracting non-smokers, including youngsters. By the same token, Griffiths (2010d) argues against certain promotional activities practised by online gambling companies, which may be commonly used in other industries, for example, loyalty schemes and promotional bonuses which reward heavy players.

These activities can fuel addiction as ‘addictions are essentially about rewards and the speed of rewards…the more potential rewards there are, the more the addictive an activity is likely to be’ (Griffiths et al. 2006, p. 37). Loss of privacy is a major concern. As online gambling companies know everything about their gamblers’ behaviour through their databases, this allows them to offer benefits and rewards including cash and ‘free bets’. However, as Griffiths et al. (2006, p. 36) observe ‘there is a very fine line between providing what the customer wants and exploitation’. However, online as well as offline gambling companies could choose to use their databases to identify and assist problem gamblers (Griffiths et al. 2006, 2009; Smeaton and Griffiths 2004), and by so doing enhance their CSR and show that they are concerned with more than revenue.

Wiebe (2008, p. 2) explains the way that online gambling companies recruit, register and retain gamblers as a three-phase process: First is recruitment, which employs a wide and far-reaching set of promotional strategies including, search engines, affiliate networks, pop‐ups, television, print, radio and sponsorships. Second is registration, which is accompanied by free games and reward for trials. The third phase, retention, is achieved by providing bonuses (first-time player, referring a customer, random draws) and rewards for desired behaviour, such as large wagers or frequent play, which include: daily, weekly or monthly rewards; cash rewards for deposits; and loyalty programmes, i.e. programmes in which a player earns points based on spending. These points can be used by VIP players to purchase merchandise or to enter tournaments or contests (Wiebe 2008, p. 2).

A study by Sevigny et al. (2005) showed that 39 % of the gambling sites studied had inflated payout rates during the demo session, i.e. over 100 %, which were not kept when gambling for actual money. They also found that some sites were instilling false beliefs about chance and randomness. This study and Wiebe’s (2008) discussion of the marketing strategy to recruit register and retain gamblers show the ability of the industry to target potential customers and keep them through the establishment of long-term relationships, which engenders customer trust and loyalty. On the one hand, these marketing activities may well reflect their effectiveness in generating business, as seen from the massive expansion of online gambling; on the other hand, it is necessary to ask whether these marketing activities are compatible with the CSR policies advocated by the industry for preventing or minimising problem gambling.

It appears, therefore, that the major challenge for the gambling industry is deciding between maximising revenue and preventing harm. It may be that preventing harm is an unrealistic hope in the absence of an obligation to do so, considering that previous research has shown that problem gamblers provide a large proportion of gambling revenue, estimated between 30 and 50 % (Hancock et al. 2008). Most of the revenue (70 %) from Electronic Gaming Machines (EGM) comes from problem gamblers (Gambling Research Australia 2008). Research in the UK has shown that most sectors of the gambling industry fail to display responsible gambling signage on EGM and, therefore, do not comply with licence conditions (Moodie and Reith 2009). Consequently, Hancock et al. (2008, p. 60) urge both the industry and the government to apply more effective policies beyond the current self-regulatory codes to protect problem gamblers, if they want to achieve a sustainable gambling industry, one that is ‘underpinned by consumer protection practices and not disproportionately reliant on the losses of problem gamblers’.

Empirical Research on Online Problem Gambling

Few studies assess online problem gambling, either broadly (Wood and Williams 2009) or with a narrow focus. Studies in the area include playing behaviour (McBride and Derevensky 2009); poker (Griffiths et al. 2010a; Wood et al. 2007); sports (LaBrie et al. 2007); emotional states (Matthews et al. 2009); health (Petry 2006); erroneous cognitions (Moodie 2008); behaviour of Internet versus non-Internet gamblers (Griffiths and Barnes 2008; Ladd and Petry 2002); and socio-demographics (Afifi et al. 2010). Even fewer studies have focused on CSR in online gambling (Griffiths et al. 2009; Smeaton and Griffiths 2004). To our knowledge, the current study is the first to integrate and measure psychological distress, problems in social relationships and academic performance in the context of online gambling, and it is one of few studies examining the physical health issues associated with this activity.

An important concern regarding online gambling is that young adults/university students seem to be targeted by online gambling companies (Smith and Rupp 2005). Gambling is particularly prevalent and problematic among university students (Lesieur et al. 1991; Neighbors et al. 2002; Shaffer et al. 1999; Winters et al. 1998) and thus students are considered a vulnerable group (Matthews et al. 2009; Moodie 2008; Wood et al. 2007). Although students have been the subject of gambling studies, these have mostly been in the US, Canada and Australia, and have had various foci, including alcohol and drug use (Lesieur et al. 1991; Winters et al. 1998), gambling motivation (Neighbors et al. 2002) and criminal behaviour (Ladouceur et al. 1994). However, research into student gambling has been largely neglected in the UK.

Moodie (2008, p. 31) argues that students are a ‘high-risk, high-priority group’, because student life is associated with risk-taking behaviour, such as alcohol consumption, illicit drugs, sexual behaviour or gambling (Winters et al. 1998). Another risk factor for problem gambling is that although students are independent, they are financially constrained (Moore and Ohtsuka 1999). Moodie (2008) found that 1 in 12 students were problem or Probable Pathological (PP) gamblers. Wiebe et al. (2006, p. 49) found that the rate of online problem gambling had increased by 44 % between 2001 and 2005, stating that ‘increasingly, Internet gambling is emerging as a high-risk area from a problem gambling standpoint’. He adds: ‘it is a highly accessible activity with high frequency of play that appeals to young adults, an age group known to have the highest rates of problem gambling’. Although previous studies on student gamblers have shown low rates of problem gambling prevalence (Neighbors et al. 2002), the latest British Gambling Prevalence Survey 2010 showed that, for the first time, those in the 16–34 age group were more likely to be considered problem gamblers compared to those aged 45 and over (Wardle et al. 2011). Therefore, our empirical research is focused on UK university students who fall within this vulnerable age range.

We assess the extent of the problem and the impact that it has on students’ lives, and how it is related to other problematic behaviour. We discuss the implications of our empirical results for theory and practice. The empirical research attempts to answer the following questions: (1) What is the extent of online problem gambling among student online gamblers in the UK? (2) Does online problem gambling impact on students’ mental and physical health, relationships, and academic performance? (3) Is problem gambling associated with the time spent on the Internet and gambling online, Internet addiction, binge drinking, cigarette smoking or parental/peer gambling? (4) What is the role of online gambling organisations in addressing online problem gambling and are they able to maintain socially responsible behaviour?

Method

Participants

Participants were university students who had gambled online during the month preceding the questionnaire. A convenience sample of 209 students from across UK universities participated in the study. Of these, 126 were males (60 %) and 83 females (40 %). The age of respondents ranged between 18 and 29 years, with an average of 21.4 years (SD = 4.39). The majority of respondents were British white (73 %), followed by Asians (12 %), Europeans (7 %), British others (5 %), and Africans (3 %).

Design and Measures

A questionnaire was developed and pre-tested on a small sample of students for validation purposes. Measures included the South Oaks Gambling Screen (SOGS), mental and physical health, relationships, academic performance, Internet addiction, time spent on the Internet and gambling online, binge drinking and cigarette smoking habits, parental/peer gambling, and demographic data.

SOGS

The SOGS was used to assess the extent of online problem gambling behaviour in the students’ sample. This instrument has been widely used in the screening of problem or pathological gambling. Although the categorisation cut-offs may sometimes vary slightly, SOGS has demonstrated validity and reliability among university students (Lesieur et al. 1991; Ladouceur et al. 1994; Moodie 2008; Neighbors et al. 2002) and in the context of online gambling (Griffiths and Barnes 2008; Matthews et al. 2009; Petry 2006). The SOGS assesses problem severity through a series of 20 items asking for the presence (scored 1) or absence (scored 0) of different pathological gambling criteria, such as whether gamblers chase losses, have problems controlling their gambling, feel guilty about gambling and believe that they have a problem (Lesieur and Blume 1987). The total score was calculated by adding the score from all the responses. A score of ‘0’ on the SOGS scale was categorised as No Problem (NP) gambler; ‘1–4’ was categorised as At Risk (AR) gambler; and a score of ‘5 and above’ was categorised as Probable Pathological (PP) gambler (following Powell et al. 1996).

Psychological Distress

Mental health is often characterised in terms of psychological distress, which is not a disease per se, but is typified by the presence during the preceding month of a set of psycho-physiological and behavioural symptoms, which are not specific to any given mental illness (Dohrenwend et al. 1980). Psychological distress was measured using the K-10 scale (Kessler and Mroczek 1994; Kessler et al. 2002). The scale, based on the work of Dohrenwend et al. (1980), uses a five-point response format for each question: all of the time (5), most of the time (4), some of the time (3), a little of the time (2), and none of the time (1). The maximum score of 50 indicated severe distress; the minimum score of 10, indicated no distress.

Physical Health, Social Relationships and Academic Performance

Questions were asked regarding the state of the physical health, relationships and academic performance of the respondents during the month preceding the questionnaire. These aspects were measured using a dichotomous response format (1 = Yes and 0 = No). Physical health was assessed by asking respondents if they had felt any of the following five conditions: muscle ache, wrist pain, back ache, sleeplessness and indigestion. The total score was computed by adding the score of each individual response so that a score of ‘0’ indicated no physical harm and a score of ‘5’ indicated severe physical harm. Social relationships were assessed by asking the respondents if their relationships with their friends, partner, family, or teachers had suffered. The total score was computed by adding the score from each response so that a score of ‘4’ indicated their social relationships had suffered severely. Academic performance was assessed by asking respondents if they had faced any of the following seven situations: reduced study hours, low grades, failed to submit an assignment, failed an exam or assignment, missed classes, arrived late to a class, or received an academic warning. The total score was computed by adding the score from each individual response: a score of ‘0’ indicated no academic problems and a score of ‘7’ indicated severe academic problems.

Internet Addiction

Young’s (1998) eight-item scale was used to measure Internet addiction among students. The scale assesses the presence (score 1) or absence (score 0) of Internet addiction. The total score was calculated by adding the score from all eight items. Internet addicts were classified as those scoring ‘5 or more’, as suggested by Young (1998).

Additional questions were included to determine the following: the time the respondents spent on the Internet and gambling online, binge drinking and cigarette smoking habits, parental/peer gambling, age, sex and ethnicity.

Procedure

The study required British university students who had gambled online in the preceding month. An online survey was deployed to a panel established and operated by a well-known market research firm in the UK. Previous studies on online gambling have also used an online survey as this seems an appropriate method for collecting data from online gamblers (Wood and Griffiths 2007; Griffiths and Barnes 2008). Because the panel originated from a broad subject pool, participants were from across UK universities who had been previously recruited for web-based research, after following a rigorous opt-in privacy protected process. Invitations were sent directly to a selected sample of 600 students via email, providing them with a link to an online questionnaire administered over a secure server (Griffiths et al. 2006). Upon entering the survey website, potential respondents were presented with screening questions to verify that they were over-18, university students and had gambled online in the month preceding the questionnaire. Only those who passed the screening were allowed to take part in the survey, and they were compensated with a small payment (£3) for their time and effort. There were 209 fully completed questionnaires. The response rate was 34.8 %, which is around the overall panel’s response rate of 36 %. Data were collected during a period of 8 weeks and participants filled in a consent form before answering the questionnaire.

Data Analysis

Three groups were identified according to the SOGS: PP gamblers, AR gamblers, and NP gamblers. One-way ANOVA tests were applied to examine differences among the groups regarding their psychological distress, physical health, social relationships, academic performance, time spent on the Internet and gambling online. The ANOVAs were followed by Tukey’s HSD post hoc comparisons to further investigate group differences. χ 2 was used to test the associations between the groups and categorical variables.

Results

Following Powell et al. (1996), three groups of gamblers were identified according to the SOGS. Of the total sample, 13 % were PP gamblers (male = 89 %; female = 11 %), 47 % were AR gamblers (male = 75 %; female = 25 %), and 40 % were NP gamblers (male = 34 %; female = 66 %). Males (PP = 89 %; AR = 75 %; NP = 34 %) were significantly more likely to be PP or AR gamblers than females (PP = 11 %; AR = 25 %; NP = 66 %) [χ 2(2) = 42.31, p < .01.]

Table 1 shows ANOVA results for the three groups of online gamblers regarding the association between their online gambling status and their mental and physical health, social relationships, academic performance, time spent on the Internet and gambling online.

Psychological Distress

The K-10 scale (Kessler and Mroczek 1994; Kessler et al. 2002) indicated good reliability (∞ = 0.92). The total score ranged between 10 and 48 with a mean of 19.94 (SD = 9.55). One-way ANOVA (Table 1) revealed significant group differences in distress mean scores [F (2, 206) = 47.91, p < .01]. Not surprisingly, PP gamblers reported the highest degree of distress, followed by AR and NP gamblers. Post hoc analyses revealed that the mean scores of PP gamblers were significantly higher than those of AR and NP gamblers. However, there was no significant difference between NP and AR gamblers.

Physical Health

One-way ANOVA (Table 1) revealed significant group differences in physical health mean scores [F (2, 206) = 126.22, p < .01]. PP gamblers reported the highest degree of health problems (an average of four out of 5 health problems), followed by the AR group (an average of three out of five) and the NP group (an average of one out of five).

Social Relationships

One-way ANOVA (Table 1) revealed significant differences in relationships mean scores among the three groups [F (2, 206) = 71.67, p < .01]. PP gamblers reported the highest degree of relationships problems with a partner, friends, family, or teachers (maximum average of 4), followed by the AR group (an average of three out of four) and the NP group (an average of one out of four).

Academic Performance

One-way ANOVA (Table 1) showed significant group differences in academic performance [F (2, 206) = 291.73, p < .01]. PP gamblers reported the highest degree of academic problems (an average of four out of seven), followed by AR gamblers (an average of three out of seven) and NP gamblers (an average of one out of seven).

Time Spent on the Internet

The total time spent on the Internet was computed. This measure included time spent gambling online and time spent on other Internet activities such as browsing, emailing, chatting and shopping. One-way ANOVA (Table 1) revealed significant differences in the number of daily hours of Internet use among the three groups of gamblers [F (2, 206) = 37.55, p < .01]. The PP group reported the longest time spent on Internet (an average of 11 h per day), followed by AR (10 h per day) and NP (8 h per day) groups. The NP group spent significantly less time on the Internet than the AR and PP groups; however, the AR and PP groups were not significantly different.

Time Spent Gambling Online

One-way ANOVA (Table 1) revealed significant differences in the number of daily hours spent gambling online among the three groups of gamblers [F (2, 206) = 247.79, p < .01]. The PP group reported spending the longest time gambling (an average of 7 h per day), followed by the AR (5 h per day) and the NP (2 h per day) groups.

The above results assessed the extent of online problem gambling and its impact on gamblers’ lives. To gain further insight into online problem gambling, we examined the relationship between online problem gambling and other problematic behaviour such as Internet addiction, binge drinking and cigarette smoking. We also examined the relationship between online problem gambling and parental/peer gambling.

Online Gambling and Other Problematic Behaviour

Internet Addiction

Three groups of Internet users were identified from Young’s (1998) eight-item scale: Internet addicts were classified as those with a score of ‘5 or more’; those who scored between ‘1 and 4’ were classified as possible Internet addicts; and Internet non-addicts had a score of ‘0’. Of the PP gamblers, 33 % were Internet addicts and 67 % were possible Internet addicts. Within the AR group, 28 % were Internet addicts, 62 % were possible Internet addicts and 10 % were Internet non-addicts. Among the NP gamblers, 33 % were Internet addicts, 60 % were possible Internet addicts, and 7 % were Internet non-addicts. Further insight into Internet addiction showed that the hours of daily Internet use varied among the three Internet addicts groups. Internet addicts reported the highest use of Internet hours per day (M = 11 h, SD = 0.96), followed by possible addicts (M = 9.3 h, SD = 1.41), and non-addicts (M = 6.12 h, SD = 0.86). χ 2 analysis showed no significant association between online problem gambling and Internet addiction [χ 2 (4) = 3.34, p = .50].

Binge Drinking and Cigarette Smoking Habits

According to the National Health Service (NHS), ‘binge drinking is drinking heavily in a short space of time to get drunk or feel the effects of alcohol’ (Drinkaware.co.uk 2012). In this study, binge drinking was defined according to the NHS’s criterion: the consumption of 8 or more units in a single session for men and 6 or more for women. χ 2 analysis showed that online problem gambling was significantly associated with binge drinking behaviour [χ 2(2) = 75.28, p < .01] as 96 % of PP gamblers and 49 % of AR gamblers reported binge drinking compared to only 3 % of NP gamblers. Cigarette smoking was measured following ASH’s (Action on Smoking and Health) criterion of 14 cigarettes on average per day for men and 12 for women (ASH 2012). However, no significant association was found between cigarette smoking and online problem gambling [χ 2(2) = 0.44, p = .80] as only a minority of respondents smoked cigarettes (23 %) with similar proportions in each group of gamblers (PP = 22 %, AR = 21 % and NP = 25).

Parental and Peer Gambling

χ 2 analysis showed that the association between online problem gambling and parental gambling was highly significant [χ 2 (2) = 15.95, p < .01] as the majority of PP gamblers (56 %) reported that their parents were also gamblers compared to only 25 % of AR gamblers and 17 % of NP gamblers. Similarly, there was a significant association between online problem gambling and peer gambling [χ 2(2) = 26.27, p < .01], as PP gamblers (78 %) reported the largest proportion of peer gambling, followed by AR (67 %), compared to only a third of NP gamblers (34 %).

Discussion and Conclusions

The empirical research suggests that online gamblers have a tendency towards problem gambling, as most of the participants (60 %) displayed this tendency, whereas 40 % were classified as NP gamblers. However, of this 60 %, only 13 % were classified as PP gamblers while nearly half (47 %) were classified as AR gamblers. Our results are consistent with previous research which suggests that people who gamble on the Internet are more likely to be problem gamblers (Griffiths and Barnes 2008; Ladd and Petry 2002). They are also in line with Petry’s (2006) study as she found that 66 % of regular Internet gamblers were PP, compared with occasional Internet gamblers (30 %) and non-Internet gamblers (8 %). Wood and Williams (2007) classified 43 % of online gamblers as PP and another 24 % as AR gamblers. Taken together, these two groups represented 67 % of their sample, which is similar to our result that the majority of online gamblers have a tendency towards problem gambling. Wood and Williams (2007, p. 537) suggested that ‘the rate of problem gambling among Internet gamblers may be 10 times higher than the rate among the general population’, which indicates the seriousness of online gambling problems.

The large proportion of problem gamblers seems to indicate a substantial increase in problem gambling. The increase is particularly high in the AR group. The importance of looking at AR gamblers has been highlighted in the latest British Gambling Prevalence Survey 2010 (Wardle et al. 2011, p. 103) as ‘the greatest volume of harm from gambling may be associated with those at low to moderate risk, simply because this group greatly outnumbers those who are at the highest risk, problem gamblers’. Although Matthews et al. (2009, p. 742) classed 19 % of respondents as PP gamblers, 18 % as AR gamblers and 63 % as NP gamblers, they hinted at an upward trend in the AR group: ‘although 63 % of respondents were non-problem gamblers, 41 % (N = 52) endorsed one or two of the SOGS responses affirmatively’ (Matthews et al. 2009, p. 743). In other words, 41 % had some gambling problems. This is almost exactly the same proportion (42 %) of respondents identified as having minimal gambling problems in Neighbor et al.’s (2002) study i.e. SOGS 1–2. This further seems to validate our result which identified 47 % as AR gamblers.

The increase in AR gamblers may come from women, as our results show that AR female gamblers are over twice (25 %) the proportion of females in the PP category (11 %). Griffiths and Barnes’ (2008) study found that female problem gamblers comprised 19 % of all problem gamblers, closer to the 25 % found in our study. A possible explanation is that women initially begin to gamble as a recreational activity, but later use it as an escape from reality or a coping mechanism (Afifi et al. 2010). This suggestion may not be too surprising given the sharp increase reported in the latest British Gambling Prevalence Survey 2010 in women’s online gambling, which nearly doubled from 3 % in 2007 to 5 % in comparison with the slight increase in men’s from 9 to 10 % in the same years (Wardle et al. 2011, p. 26). This is an important demographic change as it also shows a significant increase (52 %) in the proportion of women who are gambling online relative to men, from 33 % in 2007 to 50 % in 2010. More research is needed to investigate this trend. Nevertheless, we found that males showed significantly higher levels of problem gambling than females, which is consistent with the general view in the available literature that problem gambling tends to be a male problem (Griffiths and Barnes 2008; Moodie 2008; Sproston et al. 2000; Wood and Williams 2007).

Most importantly, Table 1 shows that, as the seriousness of the online problem gambling status increases, the harm to the physical health, mental health, social relationships and academic performance of the participants also increases. We found that PP gamblers and AR gamblers exhibited significantly higher levels of physical health problems compared to NP gamblers. These results are consistent with the small number of previous studies carried out on online gambling and related problems. Petry (2006) found that online gambling was associated with poor physical and mental health independent of age, sex, gambling site and pathological gambling status. The author argues that ‘Internet gambling is an especially troublesome activity, and prevention, early intervention and treatment efforts may need to be targeted towards individuals who wager on the Internet’ (Petry 2006, p. 425). Mean scores for psychological distress were significantly higher in the PP group compared to those in the AR and NP groups. Mean scores for problems with relationships and academic performance were significantly higher in both the PP and the AR groups compared to those in the NP group.

Although the current study appears to be the first to test psychological distress, problems with relationships and academic performance in the context of online gambling, the results are consistent with previous research on offline problem gambling. In these studies, higher psychological distress was found in pathological gamblers (Ibanez et al. 2001) and relapsed pathological gamblers (Sanders and Peters 2009), and problem gamblers appeared to gamble as a means of relieving distress caused by interpersonal trauma and perceptions of poor social support (Donnelly 2010). Previous studies have shown the adverse effects that problem gambling has on society and on wide aspects of individuals’ lives (Ladouceur et al. 1994), including the disruption of the family unit (Shaw et al. 2007). Problem gambling in adolescents was found by other studies to be linked to poor social relationships and poor academic performance (Gupta and Deverensky 1998; Gupta et al. 2004; Ladouceur et al. 1999).

In addition, our results show that online problem gambling is significantly associated with time spent gambling online: the PP group reported significantly more hours of online gambling on average per day (7 h) than the other two groups; followed by the AR group (5 h) and the NP group (2 h). These results are consistent with previous research (Griffiths and Barnes 2008). Similarly, there is a significant association between time spent on the Internet in general and online problem gambling, with both PP and AR gamblers spending significantly more hours on the Internet than NP gamblers, though no significant difference was found between PP and AR gamblers. However, no association was found between Internet addiction and online problem gambling. This finding, which supports previous research, argues that even though in some cases people seem to be addicted to the Internet itself (Young 1998; Griffiths 2000), excessive Internet users are not necessarily Internet addicts but, instead, they use this medium to engage in addictive behaviour (Griffiths 2003).

A further insight into problem gambling indicates a significant association between parental and peer gambling and the respondents’ gambling problems. More than half of the PP gamblers (56 %) reported that their parents gambled. This proportion is twice that of AR gamblers (25 %) and over three times that of NP gamblers (17 %). Similarly, the large majority of PP gamblers (78 %) and AR gamblers (67 %) reported that their peers were also gamblers, compared to only one-third of those in the NP group. The findings are consistent with previous research which shows that problem gambling is associated with parental gambling (Fisher 1993; Lesieur and Klein 1987; Lesieur et al. 1991; Winters et al. 1993). In addition, previous research has found an association between problem gambling and cigarette smoking and alcohol abuse (Griffiths et al. 2010b; McBride and Derevensky 2009; Volberg et al. 2006). Consistent with some of these studies, we found a significant association between online problem gambling and binge drinking: 96 % of the PP gamblers reported binge drinking, which is nearly twice the proportion of AR gamblers (50 %), while only 3 % of NP gamblers reported binge drinking. However, no significant association was found with cigarette smoking.

Our findings have several implications for online gambling organisations regarding their role in addressing online problem gambling and whether they can maintain socially responsible behaviour. Although there is little research on CSR in online gambling, the existing studies suggest that CSR policies in the online gambling industry are ineffective. First, there are significant variations in the breadth of gambling companies’ reporting their CSR policies, with no indicators to evince the effectiveness of such policies (Jones et al. 2007). This hinders fairness and transparency. Second, although some companies offer tools to help users to be more responsible in their playing, which might increase customers’ trust in the company (Griffiths et al. 2009), this trust might be defined more by the perception that games are fair rather than by the perception that online gambling companies do not facilitate harm or that they avoid or minimise it. In addition, only a small group of players (25 %) use CSR tools (Griffiths et al. 2009) so trust in and loyalty to the company cannot entirely be attributed to their use. Third, the implementation of CSR features in online gambling seems to have serious failures, such as poor age verification checks, and so minors are able to gamble (Smeaton and Griffiths 2004). Fourth, a large proportion of gambling revenue comes from problem gamblers (Hancock et al. 2008), which implies that they are not protected from harm or exploitation. Fifth, the use of aggressive marketing techniques to recruit and retain gamblers is controversial, e.g., the use of intensive, multi-channel advertising and promotional activity, such as loyalty programmes (Wiebe 2008) and the fact that some claims have been found false or misleading (Sevigny et al. 2005). Sixth, the provision of help for problem gamblers is ineffective, as Moodie (2008) found that less than a fifth of students knew about it. Finally, the industry places the burden of responsibility for problem gamblers on the government (Euromat 2007).

We, therefore, agree with Palazzo and Richter’s (2005) premise that controversial industries cannot conform to CSR as other industries because their products are potentially harmful. However, controversial industries should still engage at the intermediate level, or transactional level of CSR. This level refers to a corporation’s integrity, i.e. it complies with legal and moral rules and behaves with transparency and fairness, avoiding harm or taking responsibility for it, if caused. They need to ensure that they are meeting the legal and ethical commitments required of them to function as a business, but they do not appear to meet these requirements at present. This is, perhaps, because addressing these issues would pose a dilemma for online gambling companies, forcing them to decide between maximising revenue and preventing harm.

Within the narrower approach to CSR for controversial industries, we ask: should industries in this sector enjoy the use of marketing techniques commonly used in other industries? Clearly, the current marketing techniques described by Wiebe (2008) seem questionable in the case of controversial industries. These marketing activities seem very effective for revenue maximisation (as seen from the figures shown in this paper), but they may be compounding rather than minimising harm to problem gamblers. This concern is highlighted by Blaszczynski et al. (2004), who propose a review of the current industry’s marketing activities to be taken by an international collaborative stakeholders’ body. We argue that if the online gambling industry itself is to decide between revenue maximisation and harm prevention, then it is unlikely that it would decide against the former.

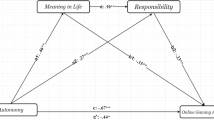

On the basis of our findings, we can answer the four questions posed in this research: (1) the extent of online problem gambling among student online gamblers in the UK is substantial; (2) online problem gambling is significantly related to students’ poor mental and physical health, poor social relationships and academic performance; (3) online problem gambling seems to be associated with the time spent on the Internet and gambling online, parental/peer gambling and binge drinking, but it does not seem to be related to Internet addiction or cigarette smoking; (4) in light of the harm related to online gambling, it is clear that the online gambling industry is unable to achieve the level of CSR common in other industries, but it is still expected to meet its legal and ethical commitments and behave with transparency and fairness in preventing or minimising such harm. Current failures in the implementation and control of CSR policies, reliance on revenue from problem gamblers and controversial marketing activities, appear to constitute the main obstacles in the prevention or minimisation of harm related to online gambling.

In conclusion, we argue that online gambling companies should be responsible for the harm related to their activities. To prevent or minimise harm, we suggest that CSR policies should be fully implemented, monitored and clearly reported; all forms of advertising should be reduced substantially; and unfair/misleading promotional techniques, such as rewarding players or offering ‘free play’ or ‘money free’ to entice and train potential players should be banned. The industry should not rely on revenue from problem gamblers, nor should their behaviour be reinforced by marketing activities, but instead, problems should be identified, with the help of the industry’s databases, so that victims can be provided with effective assistance and protective actions. While social responsibility is paramount to minimise harm and provide a healthier user experience in this business sector, it poses marketing dilemmas. Online gambling companies can gain legitimacy on the basis of the integrity of their operations, which entails behaving with transparency, consistency and fairness. The government should adopt more proactive consumer protection strategies, with the help of companies’ databases to identify problem gamblers for protective intervention. We support a global collaborative approach for the online gambling industry, as harm related to gambling constitutes a public health issue. A concerted effort involving all stakeholders will help minimise harm to individuals, their families and society. However, the suggestions proposed in this article would require policy makers and regulators to be involved, as preventing harm seems unrealistic without an obligation for the online gambling industry to do so.

Limitations and Future Research

The current study focused on university student online gamblers, so the findings are mostly relevant to this particular group. The respondents were part of an online panel and thus relatively self-selected. However, online panels have some advantages in terms of lower costs and convenience, and the possibility that respondents are more honest in providing their responses to a sensitive topic online rather than in a face-to-face survey. A methodological limitation comes from the cross-sectional design of the research, as temporal relationships among the variables remain unclear. Future research could be designed to draw causal inferences from the results to establish more clearly what comes first: online problem gambling, time spent on the Internet and gambling online, poor mental and physical health, poor social relationships or poor academic performance. Also, future studies could focus on understanding the extent to which online gambling causes problem gambling or exacerbates the condition of those with an existing gambling problem. Other research could look into demographic changes to clarify the seemingly upward trend in female problem gambling, which was identified in our research, perhaps using a sample of women and men from different age groups. Finally, other studies could also consider assessing the effect of increased CSR initiatives on problem gamblers and business results by comparing gambling companies that do practise CSR and those that do not, over time.

References

Action on Smoking and Health (ASH). (2012). Smoking statistics: Who smokes and how. Accessed February 25, 2012, from http://ash.org.uk/files/documents/ASH_106.pdf.

Afifi, T. O., Cox, B. J., Martens, P. J., Sareen, J., & Enns, M. W. (2010). Demographic and social variables associated with problem gambling among men and women in Canada. Psychiatry Research, 178, 395–400.

Australian Medical Association (AMA). (2001, January 1). Problem gambling. Accessed February 25, 2012, from http://ama.com.au/youthhealth/gambling.

Australasian Gaming Council. (2008, November). Factsheet AGC FS 17/08. Accessed August 24, 2011, from http://www.austgamingcouncil.org.au/images/pdf/Fact_Sheets/agc_fs17whatispg.pdf.

Bhattacharya, C. B., & Sen, S. (2004). Doing better at doing good: When, why and how consumers respond to corporate social initiatives. California Management Review, 47(1), 9–24.

Blaszczynski, A., Ladouceur, R., & Shaffer, H. J. (2004). A science-based framework for responsible gambling: The Reno model. Journal of Gambling Studies, 20(3), 301–317.

British Medical Association (BMA). (2007). Gambling addiction and its treatment within the NHS: A guide for healthcare professionals. London: British Medical Association.

Brown, T. J., & Dacin, P. A. (1997). The company and the product: Corporate associations and consumer product responses. Journal of Marketing, 61(1), 68–84.

Cai, Y., Jo, H., & Pan, C. (2011). Doing well while doing bad? CSR in controversial industry sectors. Journal of Business Research, published Online First: 9 November. doi:10.1007/s10551-011-1103.

Campbell, J. L. (2007). Why would corporations behave in socially responsible ways? An institutional theory of corporate social responsibility. Academy of Management Review, 32(3), 946–967.

Carroll, A. B. (1991). The pyramid of corporate social responsibility: Towards the moral management of organisational stakeholders. Business Horizons, 34(4), 39–48.

Carroll, A. B. (1999). Corporate social responsibility: Evolution of definitional construct. Business and Society, 38(3), 268–295.

Carroll, A. B. (2000). Ethical challenges for business in the new millennium. Business Ethics Quarterly, 10(1), 33–42.

Church of England. (2006, September 19). Church questions proposals for gambling advertisements. Accessed February 25, 2012, from http://www.churchofengland.org/media-centre/news/2006/09/pr9306.aspx.

Crane, A., & Matten, D. (2004). Business ethics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dawkins, J., & Lewis, S. (2003). CSR in stakeholder expectations: And their implication for company strategy. Journal of Business Ethics, 44(2/3), 185–193.

Department for Culture, Media and Sports. (2011, July 14). News releases 069/11. Accessed November 3, 2011, from http://www.Culture.gov.uk/news/media_releases/8299.aspx.

Dohrenwend, B. P., Shrout, P. E., Ergi, G. E., & Mendelsohn, F. S. (1980). Measures of non-specific psychological distress and other dimensions of psychopathology in the general population. Archives of General Psychiatry, 37, 1229–1236.

Donnelly, C. (2010). Gambling as a means of relieving distress: Understanding the connections among interpersonal trauma, perceived social support and unsupport, and problem gambling. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Carleton University, Ottawa, ON.

Drinkaware.co.uk. (2012). Binge drinking: The facts. Accessed February 25, 2012, from http://www.drinkaware.co.uk/facts/binge-drinking?gclid=CJaF6IiSlq8CFY8PfAodpi7IkA.

European Gaming and Amusement Industry (Euromat). (2007, October 25). Statement on responsible gambling. Accessed August 24, 2011, from http://www.euromat.org/uploads/documents/EUROMAT_brochure_1_web.pdf.

Fisher, S. (1993). Gambling and pathological gambling in adolescents. Journal of Gambling Studies, 9(3), 277–288.

Gambling Commission. (2012). Licence conditions and codes of practice. Accessed February 15, 2012, from http://www.gamblingcommission.gov.uk/publications_guidance__advic/lccp.aspx.

Gamcare. (2007). Online Gambling. Accessed February 15, 2012, from http://www.gamcaretradeservices.com/pages/about_us.htmlhttp.

Gambling News. (2011, January 31). Changes for online gambling in the UK. Accessed August 24, 2011, from http://www.durocher.org/gambling-news/changes-online-gambling-uk.

H2 Gambling Capital: 2011, E-Gaming Report, July 8, 2011, http://www.h2gc.com/news.php?article=Post+Q2%2FFullTilt+Closure+H2+eGaming+Dataset+Now+Available, accessed 28 October, 2011.

Gambling Research Australia (GRA). (2008). A review of australian gambling research, Chap. 4: The characteristics of EGMs and their role in gambling and problem gambling. Accessed February 28, 2012, from http://www.gamblingresearch.org.au/CA256902000FE154/Lookup/AnalysisAustGamblingResearch/$file/Chapter%204.pdf.

Goodman, A. (1990). Addiction: Definition and implications. British Journal of Addiction, 85, 1403–1408.

Gordon, R., & Moodie, C. (2009). Dead cert or long shot: The utility of social marketing in tackling problem gambling in the UK. International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing, 14, 243–253.

Griffiths, M. D. (2000). Does Internet and computer “addiction” exist? Some case study evidence. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 3, 211–218.

Griffiths, M. D. (2003). Internet gambling: Issues, concerns and recommendations. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 6(6), 557–568.

Griffiths, M. D. (2005). Does advertising of gambling increase gambling addiction? International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 3(2), 15–25.

Griffiths, M. D. (2010a). Social responsibility in marketing for online gaming affiliates. i-Gaming Business Affiliate (June/July), 32.