Abstract

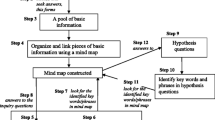

The research described here explores the idea of using Supreme Court oral arguments as pedagogical examples in first year classes to help students learn the role of hypothetical reasoning in law. The article presents examples of patterns of reasoning with hypotheticals in appellate legal argument and in the legal classroom and a process model of hypothetical reasoning that relates them to work in cognitive science and Artificial Intelligence. The process model describes the relationships between an advocate’s proposed test for deciding a case or issue, the facts of the hypothetical and of the case to be decided, and the often conflicting legal principles and policies underlying the issue. The process model of hypothetical reasoning has been partially implemented in a computerized teaching environment, LARGO (“Legal ARgument Graph Observer”) that helps students identify, analyze, and reflect on episodes of hypothetical reasoning in oral argument transcripts. Using LARGO, students reconstruct examples of hypothetical reasoning in the oral arguments by representing them in simple diagrams that focus students on the proposed test, the hypothetical challenge to the test, and the responses to the challenge. The program analyzes the diagrams and provides feedback to help students complete the diagrams and reflect on the significance of the hypothetical reasoning in the argument. The article reports the results of experiments evaluating instruction of first year law students at the University of Pittsburgh using the LARGO program as applied to Supreme Court personal jurisdiction cases. The learning results so far have been mixed. Instruction with LARGO has been shown to help law student volunteers with lower LSAT scores learn skills and knowledge regarding hypothetical reasoning better than a text-based approach, but not when the students were required to participate. On the other hand, the diagrams students produce with LARGO have been shown to have some diagnostic value, distinguishing among law students on the basis of LSAT scores, posttest performance, and years in law school. This lends support to the underlying model of hypothetical argument and suggests using LARGO as a pedagogically diagnostic tool.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The authors also caution against overuse of Socratic dialogue and the case method (Stuckey et al. 2007, pp. 97–104).

Hypothetical: being or involving a hypothesis: conjectural <hypothetical arguments> <a hypothetical situation> (2009). In Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary. Hypothesis: 1 a: an assumption or concession made for the sake of argument b: an interpretation of a practical situation or condition taken as the ground for action 2: a tentative assumption made in order to draw out and test its logical or empirical consequences 3: the antecedent clause of a conditional statement. Retrieved July 14, 2009, from http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/hypothetical.

109 Minn. 456, 560 (1910).

471 US 386, 105 S. Ct. 2066 (1985). State drug enforcement agents had received information that someone in a motor home was trading marijuana for sex. As the agents observed, a youth stepped out of a Dodge Mini Motor Home with drawn window shades parked in a downtown San Diego parking lot. After questioning him, the agents asked the youth to return to the motor home and knock on the door. Charles Carney stepped out. The agents identified themselves; one of them entered the motor home without a warrant or consent, observed drugs and drug paraphernalia, arrested Carney, and impounded the motor home. At a preliminary hearing, Carney moved to suppress the drug evidence. He argued that since he lived in his motor home, the police should have obtained a warrant before they searched it under the Fourth Amendment of the US Constitution. The lower court held that the agents had probable cause to arrest Carney, and that the search of the motor home was authorized under the automobile exception to the Fourth Amendment's warrant requirement. The California Supreme Court reversed the conviction, holding that the expectations of privacy in a motor home are more like those in a dwelling than in an automobile. The United States Supreme Court agreed to consider an appeal by the State of California.

The Carney case and accompanying oral argument have served as focal examples of legal reasoning by analogy and with hypotheticals in a series of works in the fields of AI and Law, jurisprudence, and practical ethics. See, e.g., (Rissland 1989; Hurley 1990, pp. 226–228; Newman and Marshall 1992; Brewer 1996, p. 937).

MacCormick et al. (1997) found that, “use of hypothetical cases in [academic] work…is a major technique used in the United Kingdom and in the United States, and also in most civil law countries….” It is also used in:

-

1.

“construction of clear cases to which a code section, statute or doctrine must apply if it is to have any rational application;”

-

2.

“the construction of reductio ad absurdum arguments demonstrating the unsoundness of proposed applications of code sections, statutes or doctrinal formulations;”

-

3.

“the elaboration of coherent patterns of applications of authoritative language and demonstrations of how proposed or possible applications would not be coherent,”

-

4.

“the formulation of paradigm cases so as to display a policy rationale in its clearest application;”

-

5.

“the articulation of distinctions between paradigm cases and borderline cases;”

-

6.

“the creation of conceptual bridges between cases along a continuum;”

-

7.

“use [of] a well-designed hypothetical case to help justify extending a rule;”

-

8.

use of a “hypothetical case … to help justify rejecting the application of a rule in a precedent to the case … about to be decided.”

-

1.

The decision-maker formulates and evaluates hypotheses of the form: “… ‘Reason X tends to outweigh Reason Y when it is the case that p, while Reason Y tends to outweigh Reason X when it is the case that q; when it is the case that both p and q, but not r, Reason X has more weight, but when r is present as well, Reason Y has more weight’, and so on.” Having (1) specified a problem in terms of alternative resolutions and reasons and (2) considered the purposes that underlie the reasons, a reasoner (3) gathers data, that is, settled hypothetical and actual cases, to which the reasons apply. The reasoner then (4) tries “to formulate hypotheses about the relationships between the conflicting reasons under [the] various different circumstances … which account for those resolutions. … We thus go back and forth between stages three and four, looking for settled actual and hypothetical cases that help us to refine our hypotheses about the relationships between the conflicting reasons in various circumstances.” Finally, the reasoner (5) works “out the consequences of the best hypothesis … arrived at for the original case at issue” in terms of an all-things-considered ranking (Hurley 1990, pp. 222–223, 227).

For instance, see the example in Fuller, supra Sect. 2.3, of the statute, “It shall be a misdemeanor, …, to sleep in any railway station,” and the hypothetical of the dozing “passenger who was waiting at 3 a.m. for a delayed train.”.

“(1) to clarify one’s theory (the theory may have seemed to require result A, but it really requires only B, C, and D, and, as such, remains a perfectly coherent theory); (2) to abandon one’s theory (I thought that the theory required only results B, C, and D, but it also requires result A; and since it does, and since result A is intolerable, it’s back to the drawing board); or (3) to reject people’s intuition about result A and to reaffirm one’s theory to an increasingly skeptical audience (you think that result A is intolerable, but it’s really fine on grounds of justice, or at least on grounds of administrative convenience, and so is my theory).” (4) to “reject the hypothetical on threshold grounds.” (e.g., where a hypothetical “asks for a decision on the merits of a case that” ones “theory asserts will not come up or will come up so rarely that we should not be concerned” (Gewirtz 1982, pp. 120f). Step 3 of the process model of hypothetical argument, Table 2, is based in part on Gewirtz’s first three responses.

http://www.oyez.org/ (visited July 11, 2009).

Rule 1. If you have a conjecture, set out to prove it and to refute it. Inspect the proof carefully to prepare a list of non-trivial lemmas (proof-analysis); find counterexamples both to the conjecture (global counterexamples) and to the suspect lemmas (local counterexamples). Rule 2. If you have a global counterexample discard your conjecture, add to your proof-analysis a suitable lemma that will be refuted by the counterexample, and replace the discarded conjecture by an improved one that incorporates that lemma as a condition. Do not allow a refutation to be dismissed as a monster. Try to make all ‘hidden lemmas’ explicit. Rule 3. If you have a local counterexample, check to see whether it is not also a global counterexample. If it is, you can easily apply Rule 2. (Lakatos 1976, p. 50).

Burnham v. Superior Court of California, County of Marin, 495 US 604 (1990). Dennis Burnham and his wife were married in West Virginia in 1976, moved a year later to New Jersey, and decided to separate in July, 1987. The couple agreed that they would file for divorce based on irreconcilable differences; Mrs. Burnham moved to California with their two children, while Mr. Burnham remained in New Jersey. In October, 1987, Mr. Burnham filed for divorce in New Jersey on grounds of desertion, but did not serve her with process. After unsuccessfully attempting to force Mr. Burnham to adhere to their original agreement, Mrs. Burnham filed suit against him for divorce in California in January of 1988. Later that month, on a business trip to California, Mr. Burnham visited his children and took his oldest child to San Francisco. Upon returning the child to Mrs. Burnham’s home, he was served with Mrs. Burnham’s divorce petition. After returning to New Jersey, later that year, Mr. Burnham made a special appearance in California Superior Court in order to quash the service of process on the grounds that the courts there lacked personal jurisdiction over him. He argued that his contacts with California, which consisted only of a few short visits to conduct business and visit his children, were not sufficient to grant the courts of that State jurisdiction of his person under the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. The California Superior Court denied his motion, the California Court of Appeal refused to grant mandamus relief and the Supreme Court of the United States granted certiorari.

Burnham v. Superior Court of California, 495 US 604 (1990). Burger King Corp v. Rudzewicz 471 US 462 (1985).

Kathy Keeton v. Hustler Magazine, 465 US 770 (1984).

The null hypothesis, that the mean overall scores for the two conditions were the same, could not be rejected; the probability p of the null hypothesis was p > .3.

The terms LOW, MED, and HIGH are used in a relative sense. Overall, the average of the LSAT scores of the students in the study were a bit above the average at the University of Pittsburgh School of Law.

An F-test comparison yielded F(2,25) = 4.151, p < .05 for the overall scores, and similarly for most of the subscores. This means there is strong reason to reject the null hypothesis that the mean scores on the pretest for the three groups were the same.

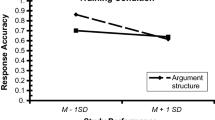

Overall, on a [0..1] scale, the Diagram group (0.57) did better than the Text group (0.52) but the difference was only marginally significant (i.e., p between .05 and .1). On the near transfer (Keeton) question, the difference was significant (Diagram (0.61); Text (0.52).) A 1-sided t-test confirmed the hypothesis (p < .05), showing an effect size of 1.99. The effect size is the difference between the two means divided by the pooled standard deviation. There was no pre-test difference between the experimental and control subgroups of LOW (p > .8 in the overall pre-test score—the pre-test did not include specific Keeton questions).

An F-test comparison yielded F(1,17) = 0.793, p < .05, 1-sided. This means there is strong reason to reject the null hypothesis that the mean scores on the hypothetical evaluation questions for the two groups were the same.

Asahi Metal Industry Co. v. Superior Court of California, 480 US 102 (1987).

45 CFR 45.101.b.1.

An F-test comparison yielded (F(1,68) = 4.250; p < .05).

An F-test comparison yielded (F(1,25) = 4.313; p < .05).

An F-test comparison yielded (F(1,10) = 5.333; p < .05).

See Sect. 8 infra for an argument that the two studies’ different starting times (October 23, 2006 v. September 5, 2007) may explain the different levels of motivation.

Id. There was a similar trend in the 2006 study, but not with respect to the 3Ls in the 2008 study, who were that much more temporally removed from having taken the LSAT exams.

See (Stuckey et al. 2007, p. 141). “[Judith Wegner] found that by the end of the first year most students have “got it,” that is, they have mastered the ability to “think like a lawyer.” According to the recommendations at p. 278, it would appear the change occurs sometime during the first semester of the first year:

A law school should not allow a student to stay enrolled beyond the first semester unless the student demonstrates the intellectual skills expected of a first semester student … that constitute the ability to ‘think like a lawyer.’

See also (Sullivan et al. 2007, p. 186):

Within months of their arrival in law school, students demonstrate new capacities for understanding legal processes, for seeing both sides of legal arguments, for sifting through facts and precedents in search of the more plausible account, for using precise language, and for understanding the applications and conflicts of legal rules. Despite a wide variety of social backgrounds and undergraduate experiences, they were learning, in the parlance of legal education, to ‘think like a lawyer.’ [emphasis added]

Neither source makes clear if the assertions are based on systematic empirical investigations. Both sources argue that “thinking like a lawyer” is at best a partial goal of legal education and that first year legal education should achieve additional goals such as complex legal problem-solving and integrating social and ethical values in decision making.

Carney Toulmin Diagram was adapted from (Newman and Marshall 1992).

456 US 798, 102 S.Ct. 2157 (1982).

445 US 573, 100 S.Ct. 1371 (1980).

Students using Toulmin-based diagrams of their own scientific arguments produced better post-test arguments than a control group in terms of evidential strength, inferential difficulty, inferential spread, and comparison to expert arguments, but the results were not statistically significant. (Suthers and Hundhausen 2001). In the context of undergraduate philosophy courses on critical thinking, students who reconstructed expert arguments from textual examples using argument diagramming achieved improvements on Critical Thinking Skills Tests comparable to those achieved from taking college or critical thinking courses. The experiments have not been controlled experiments, however. (Harrell 2007; Twardy 2004; van Gelder 2007).

An anonymous reviewer offered an alternative approach to that of Fig. 10 for applying Toulmin-style diagrams to the Carney case in order to display the structure of the argument in a way that might help students: use two diagrams, one displaying an argument for the opposite conclusion of the other. Combining elements of the argument schemes for verbal classification and analogy (Walton 1996, 54; 2005, p. 85), each argument pair would, presumably, argue the analogy for and against treating the motor home like a house, a car, and other vehicles less like a house, in terms of their respective properties relevant to the issue of whether they should be excepted from the search warrant requirement. Such arguments could be analyzed using these argumentation schemes and the schemes could be displayed on the argument diagrams as supported by Araucaria (Reed and Rowe 2004) or Rationale (van Gelder 2007). See also (Newman and Marshall 1992) for some related ideas on how to apply Toulmin-style diagrams to model the Carney argument.

See supra Sect. 2.1.

252 US 416 (1920).

See, for example, Sullivan, et al., supra note 30 at p. 35, approvingly describing the pedagogical practice of a CUNY law professor: “The students watch a short film that dramatizes a courtroom argument about the issue at hand.” Then the students are asked to compare their work with what they have watched, noting similarities and differences. The students write a short revised approach to the problem.

For instance, in the Carney case, the majority seemed to be convinced by the analogy between motor homes and automobiles that they are both subject to regulatory inspection and thus their owners have reduced expectations of privacy as compared to homes. 471 US 393. While “inspection” does not appear in the oral arguments, one justice did enquire whether the motor home required state motor vehicle registration. It did….

See supra note 32.

References

Aleven V (2003) Using background knowledge in case-based legal reasoning: a computational model and an intelligent learning environment. Artif Intell 150:183–238

Ashley K (1988) Modelling legal argument: reasoning with cases and hypotheticals. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Massachusetts at Amherst. COINS Tech Rept 88-01

Ashley K (1990) Modeling legal argument: reasoning with cases and hypotheticals. The MIT Press, Cambridge

Ashley K (2000) Designing electronic casebooks that talk back: the CATO program. Jurimetrics 40:275–319

Atkinson K, Bench-Capon T (2007) Argumentation and standards of proof. In: Proceedings of 11th international conference on artificial intelligence and law, ACM Press, 107–116

Bench-Capon T, Sartor G (2003) A model of legal reasoning with cases incorporating theories and values. Artif Intell 150(1–2):97–143

Berman D, Hafner C (1993) Representing teleological structure in case-based legal reasoning: the missing link. In: Proceedings of the fourth international conference of artificial intelligence and law, ACM Press, 50–59

Brewer S (1996) Exemplary reasoning: semantics, pragmatics, and the rational force of legal argument by analogy. Harv Law Rev 109:923–1028

Carr C (2003) Using computer supported argument visualization to teach legal argumentation. In: Visualizing argumentation, 75–96. Springer, London

Eisenberg M (1988) The nature of the common law Cambridge. Harvard University Press, MA

Fuller L (1958) Positivism and fidelity to law—a reply to Professor Hart. Harv Law Rev 71:662–664

Gewirtz P (1982) The jurisprudence of hypotheticals. J Legal Educ 32:120

Gordon T, Prakken H, Walton D (2007) The Carneades model of argument and burden of proof. Artif Intell 171:875–896

Harrell M (2007) Using argument diagramming software to teach critical thinking skills. In: Proceedings of the 5th international conference on education and information systems, technologies and applications

Harris C, Pritchard M, Rabins M (2004) Engineering ethics concepts and cases, 3rd edn. Wadsworth, Belmont

Hart HLA (1958) Positivism and the separation of law and morals. Harv Law Rev 79:593–607

Hitchcock D, Verheij B (2006) Arguing on the Toulmin model. Springer, Dordrecht

Hurley S (1990) Coherence, hypothetical cases, and precedent. Oxf J Legal Stud 10:221

Johnson T (2004) Oral arguments and decision making on the United States Supreme Court. State University of New York, Albany

Lakatos I (1976) Proofs and refutations. Cambridge University Press, London

Levi E (1949) An introduction to legal reasoning. University Chicago Press, Chicago

Lynch C, Ashley K, Pinkwart N, Aleven V (2007) Argument diagramming as focusing device: does it scaffold reading? In: Proceedings of the workshop on AIED applications for ill-defined domains at the 13th international conference on artificial intelligence in education. Los Angeles, CA, 51–60

Lynch C, Ashley K, Pinkwart N, Aleven V (2008) Argument graph classification with genetic programming and C4.5. In: Proceedings of the 1st international conference on educational data mining. Montreal, Quebec, Canada

Lynch C, Pinkwart N, Ashley K, Aleven V (2008) What do argument diagrams tell us about students’ aptitude or experience? A statistical analysis in an ill-defined domain. In: Proceedings of the workshop on ITSs for ill-defined domains: focusing on assessment and feedback at the 9th international conference on intelligent tutoring systems. Montreal, Canada. http://www.cs.pitt.edu/~collinl/ITS08/ (visited August 18, 2008)

MacCormick DN, Summers R (1997) Interpreting precedents: a comparative study. Ashgate/Dartmouth, Brookfield

Newman S, Marshall C (1992) Pushing Toulmin too far: learning from an argument representation scheme. Xerox PARC Tech Rpt SSL-92-45

Pinkwart N, Aleven V, Ashley K, Lynch C (2006) Toward legal argument instruction with graph grammars and collaborative filtering techniques. In: Ikeda et al (eds) Proceedings of ITS 2006. Springer, Berlin, 227–236

Pinkwart N, Aleven V, Ashley K, Lynch C (2007) Evaluating legal argument instruction with graphical representations using LARGO. In: Luckin R, Koedinger K, Greer J (eds) Proceedings of the 13th international conference on artificial intelligence in education (AIED2007). IOS Press, Amsterdam, 101–108

Pinkwart N, Ashley K, Aleven V, Lynch C (2008) Graph grammars: an ITS technology for diagram representations. In: Proceedings of the 21st international FLAIRS conference, special track on intelligent tutoring systems 433–438

Pinkwart N, Lynch C, Ashley K, Aleven V (2008) Reevaluating LARGO in the classroom: are diagrams better than text for teaching argumentation skills? In: Proceedings of the 9th international conference on intelligent tutoring systems. LNCS 5091. Springer, Berlin, 90–100

Prakken H (2006) Artificial intelligence and law, logic and argument schemes. In: Hitchcock D, Verheij B (eds) Arguing on the Toulmin model; new essays in argument analysis and evaluation. Springer, Dordrecht

Prakken H, Reed C, Walton D (2005) Dialogues about the burden of proof. In: Proceedings of the 10th international conference on artificial intelligence and law. ACM Press, 115–124

Prettyman EB Jr (1984) The Supreme Court’s use of hypothetical questions at oral argument. Catholic U. L. Rev. 33:555. In: Symposium on Supreme Court Advocacy

Reed C, Rowe G (2004) Araucaria: software for argument analysis, diagramming and representation. Int J AI Tools 13(4):961–980

Reese L, Cotter R (1994) A compendium of LSAT and LSAC-sponsored item types 1948–1994. Law School Admission Council Research Rept. 94-01. http://www.lsacnet.org/Research/Compendium-of-LSAT-and-LSAC-Sponsored-Item-Types.pdf (visited August 18, 2008)

Rissland E (1989) Dimension-based analysis of hypotheticals from Supreme Court oral argument. In: Proceedings of the second international conference on artificial intelligence and law. ACM Press, 111–120

Rissland E, Skalak D (1991) CABARET: rule interpretation in a hybrid architecture. Int J Man Mach Stud 34:839–887

Rowe G, Reed C (2008) Argument diagramming: the Araucaria project. In: Okada A, Buckingham Shum S, Sherborne T (eds) Knowledge cartography. Springer, London, pp 163–181

Rowe G, Macagno F, Reed C, Walton D (2006) Araucaria as a tool for diagramming arguments in teaching and studying philosophy. Teach Philos 29(2):111–124

Schauer F (1989) Is the common law law? Calif Law Rev 77:455

Schworm S, Renkl A (2007) Learning argumentation skills through the use of prompts for self-explaining examples. J Educ Psychol 99:285–296

Stuckey R et al (2007) Best practices for legal education. Clinical Legal Education Association, New York

Sullivan W, Colby A, Wegner J, Bond L, Shulman L (2007) Educating lawyers: preparation for the profession of law. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco

Suthers D, Hundhausen C (2001) Learning by constructing collaborative representations: An empirical comparison of three alternatives. In: Dillenbourg P, Eurelings A, Hakkarainen K (eds) European perspectives on computer-supported collaborative learning, proceedings of the first European conference on computer-supported collaborative learning. Maastricht, The Netherlands, 577–584

Tans O (2006) The fluidity of warrants: using the Toulmin model to analyze practical discourse. In: Hitchcock D, Verheij B (eds) Arguing on the Toulmin model; new essays in argument analysis and avaluation. Springer, Dordrecht

Toulmin S (1958) The uses of argument. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Twardy C (2004) Argument maps improve critical thinking. Teach Philos 27:95–116

Van den Braak S, van Oostendorp H, Prakken H, Vreeswijk G (2006) A critical review of argument visualization tools. ECAI-06 Workshop on computational models of natural argument, August

van Gelder T (2007) The rationale for rational™. In: Tillers P (ed) Law, probability and risk 6, (1−4):23–42, special issue on graphic and visual representations of evidence and inference in legal settings

Verheij B (2003) Artificial argument assistants for defeasible argumentation. Artif Intell 150(1–2):291–324

Voss J (2006) Toulmin’s model and the solving of ill-structured problems. In: Hitchcock D, Verheij B (eds) Arguing on the Toulmin model: new essays in argument analysis and avaluation. Springer, Dordrecht

Walton D (1996) Argumentation schemes for presumptive reasoning. Erlbaum, Mahwah

Walton D (2002) Legal argumentation and evidence. Pennsylvania State University Press, Pennsylvania

Walton D (2005) Argumentation methods for artificial intelligence in law. Springer, Berlin

Acknowledgments

This research is sponsored by NSF Award IIS-0412830. Special thanks to my collaborators in this research, Professor Vincent Aleven, co-PI, Carnegie Mellon University Human Computer Interaction Institute, Professor Niels Pinkwart, Clausthal University of Technology, Department of Informatics, Clausthal, Germany, and Collin Lynch, Graduate Research Assistant, University of Pittsburgh Intelligent Systems Program. Thanks also to my graduate student, Matthias Grabmair, for his comments and to the anonymous reviewers for valuable suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ashley, K.D. Teaching a process model of legal argument with hypotheticals. Artif Intell Law 17, 321–370 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10506-009-9083-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10506-009-9083-y