Abstract

Research on academic cheating by high school students and undergraduates suggests that many students will do whatever it takes, including violating ethical classroom standards, to not be left behind or to race to the top. This behavior may be exacerbated among pre-med and pre-health professional school students enrolled in laboratory classes because of the typical disconnect between these students, their instructors and the perceived legitimacy of the laboratory work. There is little research, however, that has investigated the relationship between high aspirations and academic conduct. This study fills this research gap by investigating the beliefs, perceptions and self-reported academic conduct of highly aspirational students and their peers in mandatory physics labs. The findings suggest that physics laboratory classes may face particular challenges with highly aspirational students and cheating, but the paper offers practical solutions for addressing them.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

We expect, actually, that the number of students actually engaging in these behaviors to be higher than the self-reported numbers suggest. Social desirability bias in survey research informs us that people will under report behaviors that are considered unacceptable, illegal or immoral by society because, even in anonymous surveys, people like to maintain positive self-impressions (Thompson and Phua 2005).

The write-up about the participants will be identical or extremely similar to the write-up appearing in two additional planned publications from this study.

The demographics are presented here for informational purposes only. Our analysis of the impact of student demographics is being written up for a separate publication.

Although studies have shown that self-reported GPAs tend to accurately reflect actual GPAs, these same studies have also found that students at the lower end of the actual GPA scale tend to overinflate their self-reported GPAs (Cassady 2001; Dobbins et al. 1993). Thus, our categorization of students with self-reported GPAs of less than 3.0 as Unrealistics is justified, given that their actual GPAs are likely too low to even be considered for admission into medical or health professional schools.

We included the following question in the survey—“We use this statement to discard the surveys of people who are not reading the statements. Please select “kind of disagree” as the answer for this statement.” 228 people selected an answer other than “kind of disagree” and so their survey responses were eliminated from the analysis.

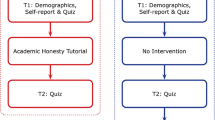

The write-up about data collection will be identical or extremely similar to the write-up appearing in other publications stemming from this study.

The list of behaviors were adapted from McCabe’s international surveys, used with permission; see McCabe 2005a for a reference.

For purposes of calculation, the following values were assigned to each choice: Not Relevant = 0; Never = 1; Sometimes = 2; Frequently = 3.

References

American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy. (n.d.). Pharmacy school admissions requirements 2010–2011. http://www.aacp.org/resources/student/pharmacyforyou/admissions/Documents/PSAR1011_Table8.pdf . Accessed 5 February 2011.

American Dental Education Association. (2007). ADEA’s official guide to dental schools 2007. http://www.dentalstudentbooks.com/dental_school_statistics.html. Accessed 5 February 2011.

Anderson, M. S. (2011). Research misconduct and misbehavior. In T. B. Gallant (Ed.), Creating the ethical academy: A systems approach to understanding misconduct and empowering change in higher education (pp. 83–96). New York: Routledge.

Association of Schools and Colleges of Optometry. (2009). Schools and colleges of optometry: Admissions requirements 2009–2010. http://www.opted.org/files/public/Admission_Requirements_09-10.pdf. Accessed 5 February 2011.

Balduf, M. (2009). Underachievement among college students. Journal of Advanced Academics, 20(2), 274–294.

Berkowitz, A. D. (2004). The social norms approach: Theory, research, and annotated bibliography. http://www.alanberkowitz.com/articles/social_norms.pdf. Accessed 4 August 2011.

Bertram Gallant, T. (2007). The complexity of integrity culture change: A case study of a liberal arts college. The Review of Higher Education, 30(4), 391–411.

Callahan, D. (2004). The cheating culture. Orlando, FL: Harcourt, Inc.

Cassady, J. C. (2001). Self-reported GPA and SAT: a methodological note. Practical assessment, research & evaluation, 7 (12). http://PAREonline.net/getvn.asp?v=7&n=12 . Accessed 1 August 2010.

Chance, Z., Norton, M. I., Gino, F., & Ariely, D. (2011). Temporal view of the costs and benefits of self-deception. PNAS early edition, 1–5 March 2011.

Conrad, P. (1986). The myth of cut-throats among premedical students: On the role of stereotypes in justifying failure and success. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 27, 150–160.

Davis, S. F., Drinan, P., & Bertram Gallant, T. (2009). Cheating in school: What we know and what we can do. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

Davis, S. F., Grover, C. A., Becker, A. H., & McGregor, L. N. (1992). Academic dishonesty: Prevalence, determinants, techniques, and punishments. Teaching of Psychology, 19, 16–20.

Del Carlo, D. I., & Bodner, G. M. (2003). Students’ perceptions of academic dishonesty in the chemistry classroom laboratory. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 41(1), 47–64.

Dobbins, G. H., Farh, J. L., & Werbel, J. D. (1993). The influence of self-monitoring and inflation of grade-point averages for research and selection purposes. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 23, 321–334.

Eccles, J. S., & Wigfield, A. (2002). Motivational beliefs, values, and goals. Annual Review of Psychology, 53, 109–132.

Finn, K. V., & Frone, M. R. (2004). Academic performance and cheating: Moderating role of school identification and self-efficacy. Journal of Educational Research, 97, 115–122.

Hard, S. F., Conway, J. M., & Moran, A. C. (2006). Faculty and college student beliefs about the frequency of student academic misconduct. The Journal of Higher Education, 77(6), 1058–1080.

Harding, T. S., Carpenter, D. D., Finelli, C. J., & Passow, H. J. (2004). Does academic dishonesty relate to unethical behavior in professional practice? An exploratory study. Science and Engineering Ethics, 10(2), 311–324.

Josephson Institute. (2010). The ethics of american youth: 2010. http://charactercounts.org/programs/reportcard/2010/installment02_report-card_honesty-integrity.html. Accessed 4 March 2011.

Kortemeyer, G. (2007). The challenge of teaching introductory physics to premedical students. Physics Teacher, 45(9), 552–557.

McCabe, D. L. (2005a). Cheating among college and university students: A North American perspective. International Journal of Educational Integrity, 1(1), 1–11.

McCabe, D. L. (2005b). It takes a village: Academic dishonesty. Liberal education, 91, 26–31.

McCabe, D. L., & Trevino, L. K. (1997). Individual and contextual influences on academic dishonesty: A multicampus investigation. Research in Higher Education, 38(3), 379–396.

Milham, J. (1974). Two components of need for approval score and their relationship to cheating following success and failure. Journal of Research in Personality, 8, 378–392.

Murdock, T. B., Hale, N. M., & Weber, M. J. (2001). Predictors of cheating among early adolescents: Academic and social motivations. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 26, 96–115.

Nonis, S., & Swift, C. O. (2001). An examination of the relationship between academic dishonesty and workplace dishonesty: A multicampus investigation. Journal of Education for Business, 76, 69–77.

Sims, R. L. (1993). The relationship between academic dishonesty and unethical business practices. Journal of Education for Business, 68, 207–211.

Thompson, E. R., & Phua, F. T. T. (2005). Reliability among senior managers of the Marlowe-Crowne short-form social desirability scale. Journal of Business and Psychology, 19(4), 541–554.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bertram Gallant, T., Anderson, M.G. & Killoran, C. Academic Integrity in a Mandatory Physics Lab: The Influence of Post-Graduate Aspirations and Grade Point Averages. Sci Eng Ethics 19, 219–235 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-011-9325-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-011-9325-8