Abstract

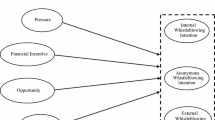

We conduct an experiment to investigate the joint effects of advisor reassurance and advice source in enhancing the impact of advice on auditors’ whistleblowing propensity. Participants from a Big 4 firm assess the likelihood that a questionable act involving a superior will be reported, both before and after receiving advice. We manipulate, between-participants, the advice source (the technical department, an authoritative source vs. a colleague, a non-authoritative source) and advisor reassurance (with vs. without) on the firm’s policy on whistleblower protection, holding constant the advice recommendation. Our study is underpinned by the premise that moral agents may require an impetus to do the right thing in the form of advice whose effects may vary by its source and nature. Results are consistent with our hypothesis. Specifically, while auditors’ propensity to report a questionable act increases after receiving advice, the increase is significantly higher when the advice is received with reassurance on whistleblower protection than without reassurance, with the effect of reassurance being greater when the advice is from an authoritative source (the technical department) than from a non-authoritative source (a colleague). These results underscore the importance of advice in promoting whistleblowing and demonstrate how the impact of advice is jointly determined by its source and reassurance on whistleblower protection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In our study, an authoritative advice source refers to an official channel (that is, the technical department) provided by the firm for employees to consult with, or to seek advice from. Prior literature also refers to the technical department as ‘Accounting Consultation Unit’ (Salterio and Denham 1997) or ‘National Office’ (Aghazadeh et al. 2019). The technical department comprises audit professionals who are knowledgeable, competent and objective and provide consultations to audit engagement teams seeking advice on complex and/or sensitive accounting, auditing, risk management, reporting issues, etc. so as to enhance audit quality (e.g., Deloitte 2019; EY 2019; KPMG 2018). A non-authoritative advice source comprises any party consulted with, such as a colleague, who is outside the firm’s official channel. Advice can be sought on both technical accounting matters (e.g., appropriateness of accounting treatment) and ethical issues/dilemmas (e.g., whether and how to report a questionable act).

Unlike consultations with colleagues which are typically done informally, consultations with the firm’s technical department can be either formal or informal. As noted by Kadous et al. (2013, Footnote 1, p. 2065), “Relative to informal advice, formal consultation is more likely to be documented or billed to the engagement and is less likely to involve auditor discretion in advisor selection and whether to follow the advice (Perkins 2003)”. Aghazadeh et al. (2019) describe recent practices in national consultation offices of Big 4 audit firms where consultations can be done verbally without being documented in the audit work papers (i.e., informally). We examine the context of informal consultation given the sensitive nature of the advice sought, which involves questionable acts of, and potential whistleblowing on, superiors within the engagement team.

While there is no SOX equivalent or an umbrella Act providing whistleblower protection in Singapore, whistleblower protection clauses are specified under various statutes, including the Companies Act, Prevention of Corruption Act, and Terrorism (Suppression of Financing) Act (Cheng 2017; McLaren et al. 2019).

Furthermore, auditors may perceive that acting on advice from an authoritative source could enable them to share with the firm the responsibility for high-risk decisions (Harvey and Fischer 1997). If the advice recipient follows advice that turns out to be bad, the auditors could shift the blame on the firm’s technical department or seek redress from the firm.

In our study, the advisor provides reassurance by restating the firm’s whistleblower protection policy. This may make the information more salient to the advisee (cognitive reassurance), and at the same time, show that the advisor has taken into account the advisee’s concerns about potential retaliation and the need for protection (affective reassurance).

We describe all advice sources as “knowledgeable and experienced” to hold constant the perceived knowledge and experience of the advisor, to ensure that there is a valid basis for participants to seek advice from these sources and potentially use their advice.

For a real case example of an audit partner succumbing to the client’s pressure to accept improper accounting treatment, see Accounting and Auditing Enforcement Release #455 (SEC 1993).

The case scenario is similar to that used in Boo et al. (2016). The description of the whistleblowing policies and procedures are consistent with those of the Big 4 firm where we conducted our experiment.

We also elicited participants’ response to this question on a dichotomous scale (i.e., yes or no). We use participants’ likelihood assessments rather than their dichotomous (yes vs. no) decisions in our tests of hypotheses as the use of continuous measures increases the power of statistical tests (Donner and Eliasziw 1994). We obtain similar results for our hypothesis tests when we use participants’ decisions instead of their likelihood assessments.

All p-values are two-tailed unless otherwise specified.

As prior literature (e.g., Birnbaum and Stegner 1979) suggests that source credibility or reliability is affected by both expertise and trustworthiness, our measure incorporates both expertise/accuracy and trustworthiness elements.

We asked several questions to measure participants’ perceptions of the audit client and the questionable act. They rated the strategic and/or economic importance of the audit client to the firm to be moderately high, with an overall mean rating of 5.7, on a scale ranging from 1 (not important at all) to 7 (absolutely important). They generally agree that the audit partner’s decision to allow the audit client to book the sales before year-end is a questionable act that should be reported, with an overall mean rating of 69%, on a scale ranging from 0% (totally disagree) to 100% (totally agree). These ratings do not vary significantly by experimental conditions (p ≥ 0.490). Although their responses to the latter question do not vary by experimental conditions, as reported later, we do find variations in participants’ propensity to whistleblow between experimental conditions. This disconnect between what professionals believe they should do and what they actually do has been shown in prior research as well (Libby and Tan 1999; Ng and Shankar 2010). We also asked participants to assess Peter’s responsibility to report the questionable act on a seven-point scale (1 = no responsibility at all; 7 = full responsibility). Results of ANOVA indicate a marginally significant main effect of Advisor Reassurance (p = 0.061), with higher perceived responsibility to report in the advisor with reassurance condition than in the advisor without reassurance condition (means = 6.1 and 5.5). Neither the main effect of Advice Source nor its interaction with Advisor Reassurance is statistically significant (p ≥ 0.601). Thus, advisor reassurance appears to positively influence participants’ perceived responsibility to whistleblow. Lastly, although participants rated the questionable act to be serious (defined as “the extent to which it is unethical, illegal or harmful”), with an overall mean rating of 6.0, on a scale ranging from 1 (not serious at all) to 7 (absolutely serious), results of ANOVA indicate, unexpectedly, a marginally higher perceived seriousness of the questionable act when advice is received from a colleague than the technical department (means = 6.3 and 5.8, respectively, p = 0.057). Neither the main effect of advisor reassurance nor its interaction with advice source is statistically significant (p ≥ 0.321). We obtain similar results for our test of hypothesis when we control for perceived seriousness as a covariate.

To provide some evidence on participants’ preference for different advice sources, we also asked participants in the debriefing questionnaire to rate how likely they would seek advice from five different sources to help them resolve highly sensitive issues that could potentially implicate their direct and/or indirect supervisors in the audit engagement, on a scale ranging from 0% (definitely not seek advice) to 100% (definitely seek advice). The means are 65% for colleagues inside the audit engagement team, 66% for colleagues outside the audit engagement, 58% for the audit firm’s technical department, 53% for the audit firm’s advice hotline manned by an independent and reputable third-party service provider for staff members to seek advice anonymously (assuming it is available), and 28% for friends outside the audit firm. Paired-sample t-tests indicate that the means for the first three advice sources which are internal to the firm are not significantly different from each other (p ≥ 0.172). However, the mean for the external advice hotline is lower than both colleagues inside the engagement team (p = 0.058) and colleagues outside the engagement team (p = 0.037) but not significantly lower than the technical department (p = 0.144). The mean for friends outside the audit firm is significantly lower than all other advice sources (p < 0.001). These results suggest that auditors perceive that they are more likely to seek advice from sources within the audit firm on ethical issues than from sources outside the firm.

The specific contrast based only on participants who passed both manipulation checks (n = 51) is also statistically significant (F = 5.169; p = 0.014, one-tailed).

For completeness, we also test the effect of advice source at each level of advisor reassurance on Report_diff. As indicated in Table 1, Panel C, in the advisor without reassurance condition, there is no statistically significant difference in Report_diff between advice sources (p = 0.826). However, in the advisor with reassurance condition, Report_diff is significantly higher when advice is received from an authoritative source than when it is received from a non-authoritative source (means = 34.4 and 22.8, respectively; p = 0.030, one-tailed).

We obtain similar results when we rerun our hypothesis test with participants’ assessed likelihood of reporting in stage 2 as our dependent variable, controlling for their assessed likelihood of reporting in stage 1 as a covariate. Results of conventional ANOVA (untabulated) indicate a statistically significant main effect of advisor reassurance (F = 8.261, p = 0.005), and a marginally significant main effect of advice source (F = 3.969, p = 0.051) but the interaction effect is not statistically significant (F = 0.859, p = 0.358). However, specific planned contrasts to test the hypothesis, with a weight of + 3 assigned to the authoritative source/reassurance condition (mean adjusted for covariate, that is, stage 1 reporting likelihood = 79.44), and + 1 to the non-authoritative source/ reassurance condition (adjusted mean = 68.92), and − 2 to the remaining conditions (adjusted means for authoritative source/no reassurance, and non-authoritative source/no reassurance = 65.81 and 62.00, respectively), is statistically significant (F = 11.458, p = 0.001, one-tailed). These results are consistent with our primary analysis. Tests of simple effects indicate that likelihood reporting in stage 2 is significantly higher in the advisor with reassurance condition than in the advisor without reassurance condition when advice is received from an authoritative source (F = 6.888, p = 0.006, one-tailed), but not from a non-authoritative source (F = 1.931, p = 0.169).

The specific contrast based only on participants who passed both manipulation checks (n = 51) is also statistically significant (F = 7.053; p = 0.006, one-tailed).

For completeness, we also test the effect of advice source at each level of advisor reassurance on advice taking. As indicated in Panel C of Table 2, there is no statistically significant difference in advice taking between advice sources (p = 0.356) in the advisor without reassurance condition. However, in the advisor with reassurance condition, advice taking is significantly higher when advice is received from an authoritative source than when it is received from a non-authoritative source (means = 0.66 and 0.44, respectively; p = 0.010, one-tailed).

We ask participants to assess, on seven-point scales (e.g., 1 = not likely at all; 7 = absolutely likely), the extent to which (1) the confidentiality of Peter’s identity will be ensured, (2) the reported questionable act will be seriously investigated, (3) Peter will be protected against negative consequences (i.e., dismissal, trouble or risk) for reporting the questionable act, (4) the questionable act could be found out or detected by others if Peter chooses not to report the questionable act, and (5) Peter would face negative consequences (i.e., dismissal, trouble, or risk) for not reporting the questionable act. The overall mean ratings are 4.0, 5.2, 4.4, 4.2, and 4.3, respectively. These ratings do not vary significantly by experiment conditions (p ≥ 0.142). As discussed in the hypothesis development, given that the reassurance does not provide any new information for the participants’ risk perceptions, the reassurance provided may not necessarily change participants’ perceived risk of reporting but could still change their whistleblowing propensity directly. A caveat of the above analyses is that we did not measure the changes in these perceptions pre- and post-advice, which may provide further insights.

References

ACFE. (2018). ACFE report to the nations on occupational fraud and abuse. Austin, TX: ACFE Association of Certified Fraud Examiners.

Aghazadeh, S., Dodgson, M. K., Kang, Y. J., & Peytcheva, M. (2019). Revealing Oz: Audit firm partners’ experiences with National Office Consultations. Working paper presented at the 25th International Symposium on Audit Research, Boston.

Arnold, D. F., & Ponemon, L. A. (1991). Internal auditors' perceptions of whistle-blowing and the influence of moral reasoning: An experiment. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 10, 1–15.

Ayers, S., & Kaplan, S. E. (2005). Wrongdoing by consultants: An examination of employees' reporting intentions. Journal of Business Ethics, 57(2), 121–137.

Bamber, E. M. (1983). Expert judgment in the audit team: A source reliability approach. Journal of Accounting Research, 21(2), 396–412.

Baudot, L., Demek, K. C., & Huang, Z. (2018). The accounting profession’s engagement with accounting standards: Conceptualizing accounting complexity through Big 4 comment letters. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 37(2), 175–196. https://doi.org/10.2308/ajpt-51898.

Bik, O., & Hooghiemstra, R. (2018). Cultural differences in auditors' compliance with audit firm policy on fraud risk assessment procedures. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 37(4), 25–48. https://doi.org/10.2308/ajpt-51998.

Birnbaum, M. H., & Stegner, S. E. (1979). Source credibility in social judgment: Bias, expertise, and the judge's point of view. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37(1), 48–74. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.37.1.48.

Bobek, D. D., Dalton, D. W., Daugherty, B. E., Hageman, A. M., & Radtke, R. R. (2017). An investigation of ethical environments of CPAs: Public accounting versus industry. Behavioral Research in Accounting, 29(1), 43–56.

Bonaccio, S., & Dalal, R. (2006). Advice taking and decision making: An integrative literature review, and implications for the organizational sciences. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 101(2), 127–151.

Bonaccio, S., & Dalal, R. (2010). Evaluating advisors: A policy-capturing study under conditions of complete and missing information. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 23(3), 227–249. https://doi.org/10.1002/bdm.649.

Boo, E., Ng, T., & Shankar, P. G. (2016). Effects of incentive scheme and working relationship on whistle-blowing in an audit setting. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 35(4), 23–38.

Bowen, R. M., Call, A. C., & Rajgopal, S. (2010). Whistle-blowing: Target firm characteristics and economic consequences. The Accounting Review, 85(4), 1239.

Brink, A. G., Lowe, D. J., & Victoravich, L. M. (2013). The effect of evidence strength and internal rewards on intentions to report fraud in the Dodd-Frank regulatory environment. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 32(3), 87–104.

Brown, V., Gissel, J., & Gordon Neely, D. (2016). Audit quality indicators: Perceptions of junior-level auditors. Managerial Auditing Journal, 31(8/9), 949–980. https://doi.org/10.1108/MAJ-01-2016-1300.

Buckless, F. A., & Ravenscroft, S. P. (1990). Contrast coding: A refinement of ANOVA in behavioral analysis. The Accounting Review, 65(4), 933–945.

Cheng, W. (2017). Responding to anonymous whistleblowers. The Business Times, Singapore, Nov. 13, 2017

Chychyla, R., Leone, A., & Minutti-Meza, M. (2019). Complexity of financial reporting standards and accounting expertise. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 67(1), 226–253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2018.09.005.

Clemmons, D. (2007). Europeans reluctant to blow the whistle. Internal Auditor, 64(4), 16.

Coia, P., & Morley, S. (1998). Medical reassurances and patients' responses. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 45(5), 377–386.

Corkery, M. (2010). Lehman whistle-blower's fate: Fired. Wall Street Journal - Eastern Edition, 255(61), C1.

Curtis, M. (2006). Are audit-related ethical decisions dependent upon mood? Journal of Business Ethics, 68(2), 191–209. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-006-9066-9.

Curtis, M., & Taylor, E. (2009). Whistleblowing in public accounting: Influence of identity disclosure, situational context, and personal characteristics. Accounting and the Public Interest, 9, 191–220.

Danos, P., Eichenseher, J. W., & Holt, D. L. (1989). Specialized knowledge and its communication in auditing. Contemporary Accounting Research, 6(1), 91–109.

Deloitte. (2019). Transparency report 2019 (Deloitte U.S.). https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/pages/regulatory/articles/transparency-report.html.

DeZoort, F. T., Hermanson, D. R., & Houston, R. W. (2003). Audit committee member support for proposed audit adjustments: A source credibility perspective. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 22(2), 189–205.

Donner, A., & Eliasziw, M. (1994). Statistical implications of the choice between a dichotomous or continuous trait in studies of interobserver agreement. Biometrics, 50(2), 550–555. https://doi.org/10.2307/2533400.

EY. (2019). Transparency report 2019 (Ernst & Young U.S.). https://www.ey.com/en_us/2019-ey-us-transparency-report.

Gao, L., & Brink, A. G. (2017). Whistleblowing studies in accounting research: A review of experimental studies on the determinants of whistleblowing. Journal of Accounting Literature, 38, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acclit.2017.05.001.

Gibbins, M., & Emby, C. (1985). Evidence on the nature of professional judgment in public accounting. In Auditing Research Symposium (pp. 181–212). University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign: Office of Accounting Research

Gleicher, F., & Petty, R. E. (1992). Expectations of reassurance influence the nature of fear-stimulated attitude change. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 28(1), 86–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-1031(92)90033-G.

Granville, III K. (1999). The implications of an organization's structure on whistleblowing. Journal of Business Ethics, 20(4), 315–326.

Guggenmos, R., Piercey, M., & Agoglia, C. (2018). Custom contrast testing: Current trends and a new approach. The Accounting Review, 93(5), 223–244. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr-52005.

Guntzviller, L. M., & MacGeorge, E. L. (2013). Modeling interactional influence in advice exchanges: Advice giver goals and recipient evaluations. Communication Monographs, 80(1), 83–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637751.2012.739707.

Harvey, N., & Fischer, I. (1997). Taking advice: Accepting help, improving judgment, and sharing responsibility. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 70(2), 117–133. https://doi.org/10.1006/obhd.1997.2697.

HistorySG. (1991). Shared values are adopted—15 Jan 1991. Retrieved from https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/history/events/62f98f76-d54d-415d-93a1-4561c776ab97

Hofstede Insights. (2020). Country comparison: Singapore. Retrieved from https://www.hofstede-insights.com/country-comparison/singapore/

IFAC. (2018). Handbook of the International Code of Ethics for Professional Accountants. New York: IFAC International Federation of Accountants.

Kadous, K., Leiby, J., & Peecher, M. E. (2013). How do auditors weight informal contrary advice? The joint influence of advisor social bond and advice justifiability. The Accounting Review, 88(6), 2061–2087. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr-50529.

Kaplan, R. (2015). Asia’s rise is rooted in confucian values. Wall Street Journal, 5th June 2018.

Kaplan, S. (1995). An examination of auditors' reporting intentions upon discovery of procedures prematurely signed-off. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 14(2), 90–104.

Kaplan, S., Pany, K., Samuels, J., & Zhang, J. (2009). An examination of the effects of procedural safeguards on intentions to anonymously report fraud. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 28(2), 273–288.

Kaplan, S., Pany, K., Samuels, J., & Zhang, J. (2012). An examination of anonymous and non-anonymous fraud reporting channels. Advances in Accounting, 28, 88–95.

Keenan, J. P. (1990). Upper-level managers and whistleblowing: Determinants of perceptions of company encouragement and information about where to blow the whistle. Journal of Business and Psychology, 5(2), 223–235. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf01014334.

Keenan, J. P. (1995). Whistleblowing and the first-level manager: Determinants of feeling obliged to blow the whistle. Journal of Social Behavior & Personality, 10(3), 571–584.

KPMG. (2018). Our relentless focus on quality. Singapore Transparency Report 2018. https://assets.kpmg/content/dam/kpmg/sg/pdf/2019/01/our-relentless-focus-on-quality.pdf.

Lee, G., & Xiao, X. (2018). Whistleblowing on accounting-related misconduct: A synthesis of the literature. Journal of Accounting Literature, 41, 22–46.

Leibowitz, M., & Reinstein, A. (2009). Help for solving CPAs ethical dilemmas. Journal of Accountancy, 207(4), 30–34.

Levy, D. M. (1954). Advice and Reassurance. American Journal of Public Health, 44(9), 1113–1118.

Lewis, D. (2006). The contents of whistleblowing/confidential reporting procedures in the UK. Employee Relations, 28(1), 76–86.

Libby, R., & Tan, H. (1999). Analysts’ reactions to warnings of negative earnings surprises. Journal of Accounting Research, 37(2), 415–435. https://doi.org/10.2307/2491415.

MacGeorge, E. L., Guntzviller, L. M., Brisini, K. S., Bailey, L. C., Salmon, S. K., Severen, K., et al. (2017). The influence of emotional support quality on advice evaluation and outcomes. Communication Quarterly, 65(1), 80–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/01463373.2016.1176945.

McLaren, J., Kendall, W., & Rook, L. (2019). Would the Singaporean approach to whistleblower protection laws work in Australia? Australasian Accounting Business and Finance Journal, 13(1), 90–108. https://doi.org/10.14453/aabfj.v13i1.5.

Miceli, M. P., & Near, J. P. (1984). The relationships among beliefs, organizational position, and whistle-blowing status: A discriminant analysis. Academy of Management Journal, 27(4), 687–705.

Miceli, M. P., & Near, J. P. (1985). Characteristics of organizational climate and perceived wrongdoing associated with whistle-blowing decisions. Personnel Psychology, 38(3), 525.

Millie, A., & Herrington, V. (2005). Bridging the gap: Understanding reassurance policing. Howard Journal of Criminal Justice, 44(1), 41–56. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2311.2005.00354.x.

Milliken, F. J., Morrison, E. W., & Hewlin, P. F. (2003). An exploratory study of employee silence: Issues that employees don’t communicate upward and why. Journal of Management Studies, 40(6), 1453–1477.

Near, J. P., & Miceli, M. P. (1986). Retaliation against whistle blowers: Predictors and effects. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71(1), 137–145.

Near, J. P., & Miceli, M. P. (1995). Effective whistle-blowing. Academy of Management Review, 20(3), 679–708.

Near, J. P., & Miceli, M. P. (1996). Whistle-blowing: Myth and reality. Journal of Management, 22(3), 507.

Ng, T. B. P., & Shankar, P. G. (2010). Effects of technical department's advice, quality assessment standards, and client justifications on auditors' propensity to accept client-preferred accounting methods. The Accounting Review, 85(5), 1743–1761.

Notbohm, M., Campbell, K., Smedema, A. R., & Zhang, T. (2019). Management’s personal ideology and financial reporting quality. Review of Quantitative Finance and Accounting, 52(2), 521–571. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11156-018-0718-5.

Parisi, R. (2009). The fine art of whistleblowing. The CPA Journal, 79(11), 6–10.

Patel, C. (2003). Some cross-cultural evidence on whistle-blowing as an internal control mechanism. Journal of International Accounting Research, 2, 69.

Perkins, J. D. (2003). Informal consultation in public accounting: A strategic view and an experimental investigation. Unpublished PhD thesis, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Pincus, T., Holt, N., Vogel, S., Underwood, M., Savage, R., Walsh, D., et al. (2013). Cognitive and affective reassurance and patient outcomes in primary care: A systematic review. Pain, 154(11), 2407–2416. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2013.07.019.

Plumlee, M., & Yohn, T. L. (2010). An analysis of the underlying causes attributed to restatements. Accounting Horizons, 24(1), 41–64. https://doi.org/10.2308/acch.2010.24.1.41.

Pope, K. R., & Lee, C.-C. (2013). Could the Dodd Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010 be helpful in reforming corporate America? An investigation on financial bounties and whistle-blowing behaviors in the private sector. Journal of Business Ethics, 112(4), 597–607. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1560-7.

Pratt, J., & Beaulieu, P. (1992). Organizational culture in public accounting: Size, technology, rank, and functional area. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 17(7), 667–684.

Robertson, J. C., Stefaniak, C. M., & Curtis, M. B. (2011). Does wrongdoer reputation matter? Impact of auditor-wrongdoer performance and likeability reputations on fellow auditors’ intention to take action and choice of reporting outlet. Behavioral Research in Accounting, 23(2), 207–234.

Rocha, E., & Kleiner, B. H. (2005). To blow or not to blow the whistle? That is the question. Management Research News, 28(11/12), 80–87.

Rogers, R. W., & Thistlethwaite, D. L. (1970). Effects of fear arousal and reassurance on attitude change. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 15(3), 227–233. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0029437.

Rose, J. M., Brink, A. G., & Norman, C. S. (2016). The effects of compensation structures and monetary rewards on managers’ decisions to blow the whistle. Journal of Business Ethics,, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-016-3222-7.

Salterio, S., & Denham, R. (1997). Accounting consultation units: An organizational memory analysis. Contemporary Accounting Research, 14, 669–691.

Schaefer, T. J. (2013). The effects of social costs and internal quality reviews on auditor consultation strategies. (Doctoral Dissertation), University of South Carolina, https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/472

Schultz, J. J., Jr., Johnson, D. A., Morris, D., & Dyrnes, S. (1993). An investigation of the reporting of questionable acts in an international setting. Journal of Accounting Research, 31, 75–103.

SEC. (1993). Accounting & Auditing Enforcement Release No. 455. Washington, D.C.: SEC: Securities and Exchange Commission.

Shankar, P. G., & Ng, T. B. P. (2008). When does advice influence auditors’ decisions? Moderating effects of performance evaluation focus and client attitude. Paper presented at the International Symposium on Audit Research, Pasadena

Sniezek, J. A., & Buckley, T. (1995). Cueing and cognitive conflict in judge-advisor decision making. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 62(2), 159–174. https://doi.org/10.1006/obhd.1995.1040.

Tan, C. H. (1989). Confucianism and nation building in Singapore. International Journal of Social Economics, 16(8), 5–16. https://doi.org/10.1108/03068298910133106.

Tavakoli, A. A., Keenan, J. P., & Crnjak-Karanovic, B. (2003). Culture and whistleblowing an empirical study of Croatian and United States managers utilizing Hofstede's cultural dimensions. Journal of Business Ethics, 43(1), 49–64.

Taylor, E., & Curtis, M. (2010). An examination of the layers of workplace influences in ethical judgments: Whistleblowing likelihood and perseverance in public accounting. Journal of Business Ethics, 93(1), 21–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-009-0179-9.

Traeger, A., Hubscher, M., Henschke, N., Moseley, G., Lee, H., & Mcauley, J. (2015). Effect of primary care-based education on reassurance in patients with acute low back pain: Systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Internal Medicine, 175(5), 733–743. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.0217.

TST. (1991). Shared values should help us develop a Singaporean identity. The Straits Times

Wainberg, J., & Perreault, S. (2016). Whistleblowing in audit firms: Do explicit protections from retaliation activate implicit threats of reprisal? Behavioral Research in Accounting, 28(1), 83–93.

Weaver, G. R., Trevino, L. K., & Cochran, P. L. (1999). Corporate ethics practices in the mid-1990's: An empirical study of the Fortune 1000. Journal of Business Ethics, 18(3), 283–294.

Westermann, K., Bedard, J., & Earley, C. (2015). Learning the “craft” of auditing: A dynamic view of auditors’ on-the-job learning. Contemporary Accounting Research, 32(3), 864–896. https://doi.org/10.1111/1911-3846.12107.

Xu, Y., & Ziegenfuss, D. (2008). Reward systems, moral reasoning, and internal auditors’ reporting wrongdoing. Journal of Business & Psychology, 22(4), 323–331.

Yaniv, I. (2004). Receiving other people’s advice: Influence and benefit. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 93, 1–13.

Yaniv, I., & Kleinberger, E. (2000). Advice taking in decision making: Egocentric discounting and reputation formation. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 83(2), 260–281.

Zhang, J., Pany, K., & Reckers, P. (2013). Under which conditions are whistleblowing “best practices” best? Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 32(3), 171–181.

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants and their firm for generous support, Charles Cho (Section Editor), two anonymous reviewers, and participants of International Symposium on Audit Research and American Accounting Association Annual Meeting for helpful comments, and Nanyang Technological University for research funding support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

Our study was approved by our institution before the establishment of an IRB at our institution. Participation was on a voluntary and anonymous basis. Subject to the above caveat, all procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Boo, E., Ng, T. & Shankar, P.G. Effects of Advice on Auditor Whistleblowing Propensity: Do Advice Source and Advisor Reassurance Matter?. J Bus Ethics 174, 387–402 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-020-04615-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-020-04615-0