Abstract

Some facts ground other facts. Some fact is fundamental iff there are no other facts which partially or fully ground that fact. According to metaphysical foundationalism, every non-fundamental fact is fully grounded by some fundamental fact(s). In this paper I examine and defend some neglected considerations which might be made in favor of metaphysical foundationalism. Building off of work by Ross Cameron, I suggest that foundationalist theories are more unified than, and so in one important respect simpler than, non-foundationalist theories, insofar as foundationalist theories allow us to derive all non-fundamental facts from some fundamental fact(s). Non-foundationalist theories can enjoy a similar sort of theoretical unification only by taking on objectionable metaphysical laws.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

I would like to leave it open whether grounding is invariably a relation between facts (as in Rosen, 2010), any sort of relata (i.e., facts, objects, propositions, whatever—as in Schaffer, 2009), or whether grounding claims are most perspicuously expressed using a sentential operator, rather than by reference to a grounding relation (as in Fine, 2001). It will be convenient, however, to continue to write in terms of facts grounding other facts.

See, e.g., Raven (2016).

I’ll leave it open whether the grounding relations just are the explanatory relations, or whether they instead underpin those explanatory relations. For discussion see Maurin (2019).

2008.

2008.

Cameron (2008, 12).

At one point Cameron says that the preference for explanatory unification is analogous to the preference for theories satisfying Ockham’s razor (Cameron, 2008, 13). But he does not say that theories which exhibit explanatory unification thereby satisfy Ockham’s razor.

Cameron ignores this detail, but it seems to me that metaphysical laws—i.e., those laws governing grounding relations—must be accounted for in any tallying of the theoretical costs associated with any theory which posits grounding. I’ll discuss metaphysical laws more below.

Cf. Swinburne (2001, 92–94).

Thus the direction in which we derive some fact from another fact need not follow the direction in which the more fundamental fact grounds the less fundamental fact. This observation becomes important in Sect. 3 below.

This idea comports well with the widely discussed notion that the simplicity of a statement is related to the compressibility of the statement, as described by the length of a computer program required to produce the statement (cf. Li and Vitányi, 2008).

Within metaphysics, both Schaffer (2015) and Bennett (2017, Ch.8 \(\S\)2.2) commend methodological principles according to which, in assessing the simplicity of a theory, we should primarily be concerned with the simplicity of the fundamental (ungrounded) posits of the theory. This methodological principle meshes well with the simplicity-based argument for metaphysical foundationalism defended in this paper. Importantly, however, both Schaffer and Bennett overlook the crucial role that the metaphysical laws posited by a theory should play in our assessment of that theory’s degree of simplicity. As we will see, proponents of non-foundationalist grounding structures can mimic the sort of theoretical unification found in foundationalist theories, but only at the cost of taking on objectionable metaphysical laws.

2003, 501–502.

2009, 340.

2015, 568, 571.

\(P(T \mid E) = \frac{P(E \mid T) \, P(T)}{P(E)}\)

Simplicity considerations in particular are crucial in allowing us to distinguish between the infinite number of theories which are equally capable of predicting our evidence (cf. Swinburne, 1997, 15).

To give one example, if mental states are grounded in physical brain states, we need to engage in empirical investigation in order to discover which physical brain states ground which mental states.

2015.

Here Morganti cites Zimmerman (1996).

Here Morganti cites Morganti (2011).

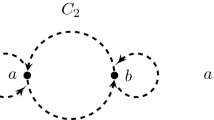

Infinitely descending grounding structures have been widely discussed, although they are not generally explicitly said to be infinitely ascending as well (i.e., such that every fact grounds some other fact). For some recent partial defenses of infinitely descending grounding structures, see Schaffer (2003), Bliss (2013) and Morganti (2014). Bohn (2009) defends the possibility of “hunky” worlds, in which every object has further proper parts, and every object is a proper part of something else. On the widely shared assumption that facts regarding composite objects are grounded in facts regarding their proper parts, a hunky world will be one in which grounding is infinite in both directions, in the sense described in the main body of the text.

Exactly which sorts of laws are “suitable” will be discussed below.

A grounding structure similar to Structure 1 would be one which is infinite in only one direction: \(\cdots \rightarrow\)F\(_{-3}\) \(\rightarrow\)F\(_{-2}\) \(\rightarrow\)F\(_{-1}\) \(\rightarrow\)F\(_{0}\). One might be tempted to think that in this case we need only posit F\(_{0}\), and from there we can derive all of the other facts in the grounding structure. But this grounding structure is plausibly logically impossible (thanks here to an anonymous referee). For any two facts in the grounding structure, those facts plausibly ground a conjunctive fact to the effect that both those facts obtain. Similarly, for any fact in the grounding structure, that fact grounds the disjunction of that fact and some other (obtaining or non-obtaining) fact. So, we cannot have a grounding structure of this sort, where some facts in the structure do not ground any other facts, and so I do not discuss this grounding structure further.

Grounding circles seem to have been endorsed by Huayan Buddhist thinkers, as conveyed, for example, in their use of the metaphor of the Net of Indra (cf. Priest, 2015; Bliss and Priest, 2018). More recently, grounding circles have been defended by Rodriguez-Pereyra 2015, Thompson (2016), Barnes (2018), Calosi and Morganti forthcoming.

Schaffer (2017a).

Brenner (2015, \(\S\)3).

Cowling (2013, 3889).

Note that I am not suggesting that backward-looking laws are by themselves more complex than forward-looking laws.

Assuming that grounding is transitive, whether grounding circles are possible will depend on whether grounding is irreflexive (on which see Jenkins, 2011; Rodriguez-Pereyra, 2015), since, given the assumption that grounding is transitive, in a grounding circle every fact grounds itself. Since most philosophers think grounding is both transitive and irreflexive, it immediately follows that they would reject grounding circles. For the sake of argument I assume in this paper that such a quick refutation of grounding circles is inadmissible.

2004.

This pocket watch thought experiment is described in Hanley (2004, 131, 133). The thought experiment is modeled after events contained in the movie Somewhere in Time.

Note that the reasoning here resembles the standard explanation for why entropy tends to increase in isolated systems: there are many more ways for a system to increase in entropy than for it to decrease in entropy, and so it is more likely that over time the system’s entropy will increase rather than decrease.

Lewis and Barnes (2016).

So, I don’t mean to suggest that all grounding circles will require these sorts of objectionable coincidences or fine-tuning. For example, there might not be objectionable fine-tuning in the case of a very simple grounding circle wherein some fact directly grounds itself. By the same token, the pocket watch thought experiment presumably couldn’t show that very simple causal circles are objectionable.

See, for example, one of Thompson’s (2016) proposed grounding circles: the mass, density, and volume of a sample of homogeneous fluid might be such that any two of them ground the other. Assuming that grounding is transitive, then in this case any of the three facts regarding the fluid (partially) grounds itself. Obviously, a grounding circle of this sort is only meant to encompass a very tiny portion of the total facts which obtain.

Orilia (2009, 339).

In fact, some cosmological arguments for theism appeal to the explanatory unification afforded by theism, and the attendant simplification of our total theory afforded by theism. For example, an argument of this sort is defended by Swinburne (2004, Ch.7, especially pp. 149–152), who argues that God is a particularly simple terminus of explanation for the existence of the complex physical universe.

References

Barnes, E. (2018). Symmetric dependence. In G. Priest & R. Bliss (Ed.), Reality and its structures: Essays in fundamentality (pp. 50–69). Oxford University Press.

Bennett, K. (2017). Making things up. Oxford University Press.

Bliss, R. (2013). Viciousness and the structure of reality. Philosophical Studies, 166(2), 399–418.

Bliss, R. (2019). What work the fundamental? Erkenntnis, 84(2), 359–379.

Bliss, R., & Priest, G. (2018). Metaphysical dependence, east and west. In S. M. Emmanuel (Ed.), Buddhist philosophy: A comparative approach. Wiley Blackwell.

Bohn, E. D. (2009). Must there be a top level? Philosophical Quarterly, 59(235), 193–201.

Bradley, D. (2018). Philosophers should prefer simpler theories. Philosophical Studies, 175(12), 3049–3067.

Brenner, A. (2015). Mereological nihilism and theoretical unification. Analytic Philosophy, 56(4), 318–337.

Brenner, A. (2017). Simplicity as a criterion of theory choice in metaphysics. Philosophical Studies, 174(11), 2687–2707.

Calosi, C., & Morganti, M. (Forthcoming). Interpreting quantum entanglement: Steps towards coherentist quantum mechanics. The British Journal for the Philosophy of Science.

Cameron, R. P. (2008). Turtles all the way down: Regress, priority and fundamentality in metaphysics. Philosophical Quarterly, 58, 1–14.

Cowling, S. (2013). Ideological parsimony. Synthese, 190(17), 3889–3908.

Dasgupta, S. (2014). The possibility of physicalism. The Journal of Philosophy, 111(9/10), 557–592.

Dixon, T. S. (2016). What is the well-foundedness of grounding? Mind, 125(498), 339–468.

Fine, K. (2001). The question of realism. Philosophers’ Imprint, 1, 1–30.

Friedman, M. (1974). Explanation and scientific understanding. The Journal of Philosophy, 71(1), 5–19.

Glazier, M. (2016). Laws and the completeness of the fundamental. In M. Jago (Ed.), Reality making (pp. 11–37). Oxford University Press.

Grajner, M. (Forthcoming). Grounding, metaphysical laws, and structure. Analytic Philosophy.

Hanley, R. (2004). No end in sight: Causal loops in philosophy, physics, and fiction. Synthese, 141(1), 123–152.

Jenkins, C. S. (2011). Is metaphysical dependence irreflexive? The Monist, 94, 267–76.

Kment, B. (2014). Modality and explanatory reasoning. Oxford University Press.

Lewis, G. F., & Barnes, L. A. (2016). A fortunate universe: Life in a finely tuned cosmos. Cambridge University Press.

Li, M., & Vitányi, P. (2008). An introduction to Kolmogorov complexity and its applications (3rd ed.). Springer.

Maurin, A.-S. (2019). Grounding and metaphysical explanation: It’s complicated. Philosophical Studies, 176(6), 1573–1594.

Morganti, M. (2011). The partial identity account of partial similarity revisited. Philosophia, 39, 527–546.

Morganti, M. (2014). Metaphysical infinitism and the regress of being. Metaphilosophy, 45(2), 232–244.

Morganti, M. (2015). Dependence, justification and explanation: Must reality be well-founded? Erkenntnis, 80(3), 555–572.

Orilia, F. (2006). States of affairs: Bradley vs. Meinong, volume 2. In V. Raspa (Ed.), Meinongian issues in contemporary Italian philosophy (pp. 213–238). Ontos Verlag.

Orilia, F. (2009). Bradley’s regress and ungrounded dependence chains: A reply to Cameron. Dialectica, 63(3), 333–341.

Paul, L. A. (2012). Metaphysics as modeling: The handmaiden’s tale. Philosophical Studies, 160, 1–29.

Priest, G. (2015). The net of Indra. In J. L. Garfield, G. Priest, K. Tanaka, & Y. Deguchi (Eds.), The moon points back. Oxford University Press.

Rabin, G. O., & Rabern, B. (2016). Well founding grounding grounding. Journal of Philosophical Logic, 45, 349–379.

Raven, M. J. (2016). Fundamentality without foundations. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 93(3), 607–626.

Rodriguez-Pereyra, G. (2015). Grounding is not a strict order. Journal of the American Philosophical Association, 1(3), 517–534.

Rosen, G. (2006). The limits of contingency. In F. MacBride (Ed.), Identity and modality (pp. 13–39). Oxford University Press.

Rosen, G. (2010). Metaphysical dependence: Grounding and reduction. Logic, and epistemology. In B. Hale & A. Hoffmann (Eds.), Modality: Metaphysics (pp. 109–136). Oxford University Press.

Rosen, G. (2017). Ground by law. Philosophical Issues, 27, 279–301.

Schaffer, J. (2003). Is there a fundamental level? Noûs, 37(3), 498–517.

Schaffer, J. (2009). On what grounds what. In D. J. Chalmers, D. Manley, & R. Wasserman (Eds.), Metametaphysics (pp. 347–83). Oxford University Press.

Schaffer, J. (2015). What not to multiply without necessity. Australasian Journal of Philosophy, 93(4), 644–664.

Schaffer, J. (2016). Grounding in the image of causation. Philosophical Studies, 173(1), 49–100.

Schaffer, J. (2017a). The ground between the gaps. Philosophers’ Imprint, 17(11), 1–26.

Schaffer, J. (2017b). Laws for metaphysical explanation. Philosophical Issues, 27, 302–321.

Schindler, S. (2018). Theoretical virtues in science: Uncovering reality through theory. Cambridge University Press.

Swinburne, R. (1997). Simplicity as evidence of truth. Marquette University Press.

Swinburne, R. (2001). Epistemic justification. Clarendon Press.

Swinburne, R. (2004). The existence of God (2nd ed.). Clarendon Press.

Thompson, N. (2016). Metaphysical interdependence. In M. Jago (Ed.), Reality making (pp. 38–56). Oxford University Press.

Wilsch, T. (2015). The nomological account of ground. Philosophical Studies, 172(12), 3293–3312.

Zimmerman, D. W. (1996). Could extended objects be made out of simple parts? An argument for atomless gunk. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 56, 1–29.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Rebecca Chan, Nevin Climenhaga, Peter Finocchiaro, David Mark Kovacs, Anna-Sofia Maurin, Alexander Skiles, Naomi Thompson, and anonymous referees. Work on this paper was supported by Riksbankens Jubileumsfond.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Brenner, A. Metaphysical Foundationalism and Theoretical Unification. Erkenn 88, 1661–1681 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10670-021-00420-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10670-021-00420-x