Abstract

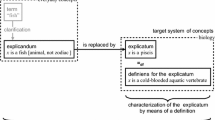

Carnap and Goodman developed methods of conceptual re-engineering known respectively as explication and reflective equilibrium. These methods aim at advancing theories by developing concepts that are simultaneously guided by pre-existing concepts and intended to replace these concepts. This paper shows that Carnap’s and Goodman’s methods are historically closely related, analyses their structural interconnections, and argues that there is great systematic potential in interpreting them as aspects of one method, which ultimately must be conceived as a component of theory development. The main results are: an adequate method of conceptual re-engineering must focus not on individual concepts but on systems of concepts and theories; the linear structure of Carnapian explication must be replaced by a process of mutual adjustments as described by Goodman; Carnap’s condition of similarity can be analysed into two components, one securing a relation to the specific extensions of the pre-existing concepts, one regulating the transition to the new system of concepts; these two criteria of adequacy can be built into Goodman’s account of reflective equilibrium to ensure that the resulting concepts promote theoretical virtues while being sufficiently similar to the concepts we started out with.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

I use italics to indicate that “terrorist” refers to the concept of being a terrorist, not to terrorists.

See the remarks in Carnap 1963b: pp. 933–939; SA:ch. I.1–2; FFF:66–7.

The following analysis covers only part of the development that led to Rawls’s exposition of the method of RE in A Theory of Justice. Rawls built on at least four sources: the logical empiricists’ work on epistemology, inductive logic and physicalism (see Rawls 1950:ch. I.6); his own earlier work (1950, 1999b, d); Chomsky’s conception of competence and performance (1965:§§ 1–2); and Goodman’s views published in Fact, Fiction, and Forecast (mentioned in Rawls 1999c: p. 18n7). There are studies on the development of Rawls’s methodological thinking (e.g. Mikhail 2010; Mäkinen and Kakkuri-Knuuttila 2013) and on Chomsky’s influence (e.g. Daniels 1980; Mikhail 2010), but although it is well known that Rawls’s ideas are related to Goodman’s, this historical line has never been studied in detail.

Astonishingly, this explicit link from RE to Goodman’s theory of definitions in SA has virtually gone unnoticed in the literature. So it may be worth pointing out that Goodman’s exposition of RE in FFF is not limited to ch. III.2, which contains the invariably quoted passages on mutual adjustment and virtuous circularity: it is continued in the opening paragraphs of ch. III.3, and there Goodman links RE to his theory of definitions.

e.g. SA:L, 19n8; Goodman 1972a: p. 4. Ch. I of SA is titled “constructional definition” but indexed as “constructional or explicative definition”.

Since then, the connection has occasionally been recognized in the literature (e.g. Hanna 1968: p. 29; Hellman 1977: pp. XXVII–XXVIII; Kantorovich 1993: p. 122; Elgin 1997; Cohnitz and Rossberg 2006: p. 62), and an explicit link from RE to (Quine’s account of) the method of explication can be found in Rawls (1999c: pp. 95–96). But to my knowledge no in-depth analysis has been given so far.

Since this section aims only at substantiating the thesis of a common project, other historical issues must be left unaddressed, specifically the sources on which Carnap and Goodman built (e.g. Russell’s (1993; 1954:ch VI–VIII) and Whitehead’s (1919) logical constructions), the relation of Carnap’s and Goodman’s proposals to related ideas put forward by contemporaries (e.g. Hempel 1952; Pap 1949; Quine 1960) and questions of precedence, for example, who first came up with the example of fish and whale in this context (Goodman used it in 1990: pp. 49–50).

Of course, this example is tailored to expository purposes, not a piece of up-to-date biological taxonomy.

See Brun 2016 for a more extensive discussion of many of the points made in the rest of this section.

Carnap identified concepts with certain non-linguistic abstract entities (LFP 7–8) and thereby tied his account of explication to his semantics. Since nothing in his account depends on whether we adopt his view of concepts, I generalize it by using “concept” to refer to an elementary linguistic entity, a “term”, together with rules for its use. And I take a neutral stance on the nature of such rules; they may specify a term’s intension or extension; they may be stated explicitly or be given implicitly in usage, fairly clearly or rather turbidly. I also leave open how such rules are related to mental or abstract entities which are often called “concepts”.

A third limitation is discussed in Brun (2016).

Actually, many authors are ready to speak of the explication of, for example, systems of concepts or theories. But explicit discussions of how Carnap’s ideas could be extended to more complex explicanda have been scarce. Exceptions include Hegselmann (1985) and Martin (1973), but they assume that reducing vagueness is the goal of explication.

Some remarks on terminology: following Goodman, I refer to his method of conceptual re-engineering as “constructional definition”. But I avoid his use of “definition”, “definiens” and “definiendum” and continue to speak of “explication”, “explicandum” and “explicatum” (also because, as will shortly become clear, constructional ‘definitions’, just like explications, have a more complex structure than definitions in the usual sense). I also continue to use Carnap’s “similarity” despite Goodman’s attacks on this notion (see 1972b). In the present context the notion of similarity does no substantial work; it has to be spelled out in terms of the explicandum’s features an explication is supposed to preserve.

Goodman does not claim that extensional isomorphism is the criterion of similarity for every kind of explication, but leaves open the possibility that in some cases other criteria are needed (1972a: p. 84).

We can assume that the explicatum is introduced by a definition, since Goodman deals with this case only.

A similar argument can be made in the case of explications that reduce vagueness.

The footnote explains “presystematically” as “according to the understood or express informal explication of what is to be defined. This explication normally accords in general with ordinary usage, trimmed and patched in various ways for various purposes” (SA 19n8). This explanation was introduced in the second edition (SA 1966, 25). In the first edition (SA 1951, 22), it simply reads “I use ‘presystematically’ for ‘according to ordinary usage”’, which is not quite correct as we have seen. Goodman’s use of “informal explication” may evoke misunderstandings, such as that the concept he calls the “definiendum” may be the product of clarifying the explicandum or of an explication in Carnap’s sense. Goodman also does not use “presystematic” is the sense in which I use “pre-theoretical”. “Presystematic” does not imply that the explicandum\(_{2}\) is in actual pre-theoretical use; it merely emphasizes that the explicandum\(_{2}\) is not part of the target system of concepts.

I will often use “adjusting the explicandum” as an abbreviation for “adjusting the extension of the explicandum”. “Adjusting” is meant to include the limiting case of leaving the extension of the explicandum unchanged.

See Goodman’s remark (“normally accords in general”) quoted in note 22.

One might see this as addressing Strawson (1963) subject-change challenge, but this is not intended (I discuss Strawson’s challenge in Brun (2016)). The requirement of extensional overlap gives the worry of a “subject change” a related but different interpretation. For Strawson, the explicandum is the subject and hence replacing it by another concept always amounts to changing the subject. Constructional re-engineering, on the other hand, aims at replacing concepts and the condition in the main text only expresses that a complete change in extension would result in changing the subject.

In passing, we may note that Carnap’s fourth criterion, simplicity, is dealt with under the labels “naturalness” and “technical efficiency” in SA (not to be conflated with simplicity as analysed in ch. III of SA). They refer to the psychological ease of handling the explicata and the degree of complexity that is needed for introducing all the explicata we want to introduce (SA 19–20).

Note that this form of pluralism differs from pluralism resulting from different ways of adjusting the extension of the explicandum.

For an extended discussion of Goodman’s example, see SA 10–16. More examples can be found especially in Part Two of SA, where Goodman uses his methodology of constructional definition to actually develop a constitutional system as an alternative to Carnap’s Aufbau (2003).

Since, according to Goodman, the structure of justification is the same in both cases, I will generally omit “inductive” and “deductive”.

For a more realistic illustration of how the method of RE may be put into action, one could also turn to Goodman’s own work on confirmation theory and induction in FFF. However, although Goodman clearly saw himself as applying RE, he did not explicitly comment on how he worked through subsequent adjustments towards a state of equilibrium. A methodological reconstruction of his actual practice of theory development would require a case study which lies outside the scope of this paper (see Hahn 2000, ch. 2.1 for a relatively short analysis).

Numbers with asterisks are used to refer to inferences or rules which are rejected rather than accepted.

When referring to what is justified by being in agreement with logical principles, Goodman simply speaks of “an inference”, “a deduction” or “an argument”. When referring to what justifies or subverts logical principles, he appeals to “accepted in/deductive practice”, “accepted inferences” and “inacceptable inferences”, or more explicitly to “the particular inferences we actually make and sanction”, “judgments rejecting or accepting particular inferences” and “normally accepted [inductive] judgments” (FFF 63–5).

For example, I can express the same validity commitment by asserting “(1) is a valid inference”, and by inferring that Aristotle was in Asia given that I have become convinced that he was in Persia and that he was in Asia if he was in Persia.

This means that Goodman presupposes a pre-theoretical distinction (i.e. a distinction made in everyday language or in a preceding stage of theory) between valid and invalid inferences, but not that he assumes this distinction to be fully embodied in ordinary usage of “valid” or that there is a sharp pre-theoretical distinction between formal validity (i.e. validity in virtue of logical form) and material validity.

I follow Scheffler (1954) and Elgin (1996) in using “commitment” and avoid the more usual “judgement” to block the misunderstanding that commitments must be explicit or conscious. Note that in the technical sense in which I use “commitment” here, commitments involve a propositional attitude of, e.g. accepting or believing, but they need not be strong, acknowledged or reflected.

In FFF 63–5, he speaks only of “conform”, “accord”, “agree” or “codify”.

Consistency may be required for a positive and a negative reason. Agreement is usually interpreted as demanding coherence, which clearly implies consistency. And according to many logics, an inconsistent set of propositions entails every proposition whatsoever, which makes an agreement between inconsistent sets of commitments and principles uninteresting and blocks them from justifying anything.

Goodman emphasizes in many places (beginning with 1990:p. v) that this does not mean that justification is to be had cheaply. It does not imply that we can always justify more than one system of principles and even less that any old system of principles can be justified.

See FFF 64 quoted above; Goodman explicitly reinforced this point in a late interview (1995: p. 347).

In an earlier version, Goodman explicitly wrote: “The sign ‘=\(_{df}\)’ [...] indicates a rule of translation between the formal system and ordinary discourse” (Goodman 1990: p. 77).

These questions, as far as I know, have never been raised in the literature on RE, not even in Hahn’s (2000) extensive discussion of SA.

Nagel (2007) argues that this contrast constitutes a fundamental difference between explication and RE. If the analysis given here is correct, this overstates the case, because RE is less an alternative than a further development of the method of explication.

Thanks to an anonymous reviewer for prompting me to say more about Carus’s proposals.

As I introduce it here, the requirement of respecting antecedent commitments is actually Carnap’s criterion of similarity transposed into the framework of reflective equilibrium. The resulting conception of reflective equilibrium is therefore not in danger of being inherently more “conservative” than explication as suggested by Dutilh Novaes and Geerdink (2017).

He mentions “convenience”, “theoretical utility” (FFF 66), “maximum coherence and articulation”, “economy”, “resultant integration” (FFF 47, referred to in FFF 65n2), and via the link to SA (in FFF 67n3) we can add “simplicity” of conceptual resources (SA ch. III.3). Goodman worked extensively on two theoretical virtues, confirmation and conceptual simplicity (in FFF and SA respectively).

Since RE is often understood as a coherentist account of justification, one may wonder whether coherence should not replace the list of theoretical virtues or at least be included in it. However, the first option is too restrictive (excluding e.g. numerical precision); the second is unsuitable because some crucial aspects of coherence (consistency of commitments and principles as well as agreement of commitments and principles) are built into RE as necessary conditions.

Just as in the case of explication and constructional definition, the necessity of trade-offs is also a reason for expecting and actually welcoming that RE allows for justifying alternative systems.

References

Bar-Hillel, Y., & Carnap, R. (1953). Semantic information. British Journal for the Philosophy of Science, 4, 147–57.

Baumberger, C. (forthcoming). Explicating objectual understanding. Taking degrees seriously. Journal for General Philosophy of Science.

Baumberger, C., & Brun, G. (2016). Dimensions of objectual understanding. To appear in S.R. Grimm, C. Baumberger, S. Ammon (Eds). Explaining understanding. New perspectives from epistemology and philosophy of science (pp. 165–189). New York: Routledge.

Brun, G. (2014a). Reconstructing arguments: Formalization and reflective equilibrium. Logical Analysis and History of Philosophy, 17, 94–129.

Brun, G. (2014b). Reflective equilibrium without intuitions? Ethical Theory and Moral Practice, 17, 237–252.

Brun, G. (2016). Explication as a method of conceptual re-engineering. Erkenntnis, 81, 1211–1241.

Cappelen, H. (forthcoming). Fixing Language. An Essay on Conceptual Engineering. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Carnap, R. (1945). The two concepts of probability. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 5, 513–532.

Carnap, R. (1956) [1947]. Meaning and necessity. A study in semantics and modal logic (2nd ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Carnap, R. (1962) [1950]. Logical foundations of probability (2nd ed.). Chicago/London: University of Chicago Press/Routledge and Kegan Paul. Referenced as LFP.

Carnap, R. (1963a). Intellectual autobiography. In P. A. Schilpp (Ed.), The philosophy of Rudolf Carnap (pp. 3–84). La Salle: Open Court.

Carnap, R. (1963b). Replies and systematic expositions. In Schilpp, P. A. (Ed.). The philosophy of Rudolf Carnap (pp. 859–1013). La Salle: Open Court. Referenced as RSE.

Carnap, R. (2003) [1928/34]. The logical structure of the world. In: Pseudoproblems in philosophy. Chicago/La Salle: Open Court.

Carus, A. W. (2007). Carnap and twentieth-century thought. Explication as enlightenment. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Chomsky, N. (1965). Aspects of the theory of syntax. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Cohnitz, D., & Rossberg, M. (2006). Nelson Goodman. Montreal/Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Daniels, N. (1980). On some methods of ethics and linguistics. Philosophical Studies, 37, 21–36.

Daniels, N. (2016). Reflective equilibrium. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.) The Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy. http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2016/entries/reflective-equilibrium/.

DePaul, M. R. (2011). Methodological issues reflective equilibrium. In C. Miller (Ed.), The continuum companion to ethics (p. lxxv-cv). London: Continuum.

Douglas, H. (2013). The value of cognitive values. Philosophy of Science, 80, 796–806.

Dutilh Novaes, C., & Reck, E. (2017). Carnapian explication, formalisms as cognitive tools, and the paradox of adequate formalization. Synthese, 194, 195–215.

Dutilh Novaes, C., & Geerdink, L. (2017). The dissonant origins of analytic philosophy. Common sense in philosophical methodology. In S. Lapointe & C. Pincock (Eds.), Innovations in the history of analytical philosophy (pp. 69–102). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Elgin, C. Z. (1983). With reference to reference. Indianapolis: Hackett.

Elgin, C. Z. (1996). Considered judgment. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Elgin, C. Z. (1997). Volume introduction. In C. Z. Elgin (Ed.). Nominalism, constructivism, and relativism in the work of Nelson Goodman (pp. xiii–xvii). New York: Garland. (= The Philosophy of Nelson Goodman. Selected Essays; Vol. 1).

Goodman, N. (1963) [1956]. The significance of Der logische Aufbau der Welt. In P. A. Schilpp (Ed.), The philosophy of Rudolf Carnap (pp. 545–58). La Salle: Open Court.

Goodman, N. (1968). Languages of art. An approach to a theory of symbols. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill.

Goodman, N. (1972a). Problems and projects. Indianapolis/New York: Bobbs-Merrill.

Goodman, N. (1972b) [1970]. Seven strictures on similarity. In Goodman 1972a: pp. 437–446.

Goodman, N. (1977) [1951]. The structure of appearance (3rd ed.). Dordrecht/Boston: Reidel. (1st ed. 1951. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. 2nd ed., 1966, Bobbs-Merrill, Indianapolis.) Referenced as SA.

Goodman, N. (1983) [1954]. Fact, fiction, and forecast (4th ed.). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Referenced as FFF.

Goodman, N. (1990) [1941]. A study of qualities. New York: Garland.

Goodman, N. (1995). Gewißheit ist etwas ganz und gar Absurdes. Karlheinz Lüdeking sprach mit Nelson Goodman. Kunstforum, 131, 342–347.

Griffin, J. (2008). On human rights. New York: Oxford University Press.

Haas, G. (2015). Minimal verificationism. On the limits of knowledge. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Hahn, S. (2000). Überlegungsgleichgewicht(e). Prüfung einer Rechtfertigungsmetapher. Freiburg/München: Alber

Hanna, J. F. (1968). An explication of explication. Philosophy of Science, 35, 28–44.

Harper, W. L. (1981). A sketch of some recent developments in the theory of conditionals. In W. L. Harper, R. Stalnaker, & G. Pearce (Eds.), Ifs. Conditionals, belief, decision, chance, and time (pp. 3–38). Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Hegselmann, R. (1985). Formale Dialektik. Ein Beitrag zu einer Theorie des rationalen Argumentierens. Hamburg: Meiner.

Hellman, G. (1977). Introduction. In SA XV–XLVII.

Hellman, G. (1978). Accuracy and actuality. Erkenntnis, 12, 209–228.

Hempel, C. G. (1952). Fundamentals of concept formation in empirical science. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Hempel, C. G. (1953). Reflections on Nelson Goodman’s the structure of appearance. The Philosophical Review, 62, 108–116.

Hempel, C. G. (1970). Aspects of scientific explanation. Aspects of scientific explanation and other essays in the philosophy of science (pp. 331–496). New York: Free Press.

Hempel, C. G. (2000) [1988]. On the cognitive status and the rationale of scientific methodology. In Selected philosophical essays (pp. 199–228). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Justus, J. (2012). Carnap on concept determination. Methodology for philosophy of science. European Journal for the Philosophy of Science, 2, 161–179.

Kant, I. (1998). [1781/1787]. Critique of pure reason. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kantorovich, A. (1993). Scientific discovery. Logic and tinkering. New York: State University of New York Press.

Kuhn, T. S. (1977). Objectivity, value judgment, and theory choice. In The essential tension. Selected Studies in Scientific Tradition and Change. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, pp. 320–39.

Kuipers, T. A. F. (2007). Introduction. Explication in philosophy of science. In Kuipers, T. A. F. (Ed.). Handbook of the philosophy of science. Focal issues (pp. vii–xxiii). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Leitgeb, H. (2017). The stability of belief. How rational belief coheres with probability. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lutz, S. (2012). Artificial language philosophy of science. European Journal for the Philosophy of Science, 2, 181–203.

Maher, P. (2007). Explication defended. Studia Logica, 86, 331–341.

Maher, P. (2010). What is probability? MS. http://patrick.maher1.net/preprints/pop.pdf. Accessed April 17, 2016.

Mäkinen, J., & Kakkuri-Knuuttila, M.-L. (2013). The defence of utilitarianism in early rawls. A study of methodological development. Utilitas, 25, 1–31.

Martin, M. (1973). The explication of a theory. Philosophia, 3, 179–199.

Mikhail, J. (2010). Rawls’ concept of reflective equilibrium and its original function in a theory of justice. Washington University Jurisprudence Review, 3, 1–30.

Miller, R. B. (2000). Without intuitions. Metaphilosophy, 31, 231–250.

Nagel, J. (2007). Epistemic intuitions. Philosophy Compass, 2, 792–819.

Olsson, E. J. (2015). Gettier and the method of explication. A 60 year old solution to a 50 year old problem. Philosophical Studies, 172, 57–72.

Pap, A. (1949). The philosophical analysis of natural language. Methodos, 1, 344–369.

Pinder, M. (2017). Does experimental philosophy have a role to play in carnapian explication? Ratio, https://doi.org/10.1111/rati.12164.

Prior, A. N. (1960). A runabout inference-ticket. Analysis, 21, 38–39.

Quine, W. V. O. (1960). Word and object. Cambridge, MA.: MIT Press.

Quine, W. V. O. (1980) [1951]. Two dogmas of empiricism. In From a logical point of view. Nine Logico-philosophical essays. (2nd Ed., pp. 20–46). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Rawls, J. (1950). A study in the grounds of ethical knowledge. Considered with reference to judgments on the moral worth of character. PhD dissertation, Princeton University.

Rawls, J. (1999a) [1974–5]. The independence of moral theory. In Collected papers (pp. 286–302). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Rawls, J. (1999b) [1951]. Outline of a decision procedure for ethics. In Collected papers (pp. 1–19). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Rawls, J. (1999c). A theory of justice (revised ed.). Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press.

Rawls, J. (1999d) [1955]. Two concepts of rules. In Collected papers (pp. 20–46). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Reck, E. (2012). Carnapian explication. A case study and critique. In P. Wagner (Ed.), Carnap’s ideal of explication and naturalism (pp. 96–116). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Russell, B. (1954). Mysticism and logic and other essays. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Russell, B. (1993) [1914]. Our knowledge of the external world as a field for scientific method in philosophy. London: Routledge.

Scanlon, T. M. (2008). Moral dimensions. Permissibility, meaning, blame. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Scheffler, I. (1954). On justification and commitment. Journal of Philosophy, 51, 180–190.

Shepherd, J., & Justus, J. (2015). X-Phi and Carnapian explication. Erkenntnis, 80, 381–402.

Schupbach, J. N. (2017). Experimental explication. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 94, 672–710.

Stein, E. (1996). Without good reason. The Rationality debate in philosophy and cognitive science. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Strawson, P. F. (1963). Carnap’s views on constructed systems versus natural languages in analytic philosophy. In P. A. Schilpp (Ed.), The philosophy of Rudolf Carnap (pp. 503–18). La Salle: Open Court.

Tarski, A. (1983) [1933]. The concept of truth in formalized languages. Logic, semantics, metamathematics (2nd Ed., pp. 152–278). Hackett: Indianapolis.

Tarski, A. (2002) [1936]. On the concept of following logically. History and Philosophy of Logic, 23, 155–196.

Tersman, F. (1993). Reflective equilibrium. An essay in moral epistemology. Stockholm: Almqvist and Wiksell.

Vermeulen, I. (2013). Words matter. a pragmatist view on studying words in first-order philosophy. PhD thesis, University of Sheffield. http://etheses.whiterose.ac.uk/id/eprint/4759.

Whitehead, A. N. (1919). An enquiry concerning the principles of natural knowledge. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Acknowledgements

The research for this paper is part of the project “Reflective Equilibrium – Reconception and Application” (Swiss National Science Foundation Project 150251). It draws on material I wrote while I was a visiting scholar at Harvard University (supported by SNSF Grant 125823). Earlier versions have been presented in Berne, Frankfurt a.M., Prague and Zürich. I would like to thank the audiences, two anonymous reviewers of this journal and especially Christoph Baumberger, Claus Beisbart, Catherine Elgin, Leon Geerdink, Jaroslav Peregrin, Geo Siegwart, Vladimír Svoboda and Nicolas Wüthrich for helpful comments and discussions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Brun, G. Conceptual re-engineering: from explication to reflective equilibrium. Synthese 197, 925–954 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-017-1596-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-017-1596-4