Abstract

Instrumental rationality prohibits one from being in the following state: intending to pass a test, not intending to study, and believing one must intend to study if one is to pass. One could escape from this incoherent state in three ways: by intending to study, by not intending to pass, or by giving up one’s instrumental belief. However, not all of these ways of proceeding seem equally rational: giving up one’s instrumental belief seems less rational than giving up an end, which itself seems less rational than intending the means. I consider whether, as some philosophers allege, these “asymmetries” pose a problem for the wide-scope formulation of instrumental rationality. I argue that they do not. I also present an argument in favor of the wide-scope formulation. The arguments employed here in defense of the wide-scope formulation of instrumental rationality can also be employed in defense of the wide-scope formulations of other rational requirements.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

See, for example, Schroeder (2004, 2009), Kolodny (2005), and Bedke (2009). This paper will respond to the particular versions of this objection given by Schroeder and Bedke. Kolodny’s version of the asymmetry objection introduces additional complexities, which I consider and respond to in Brunero (2010).

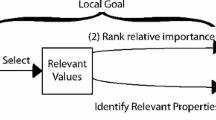

Section 1 is largely concerned with the asymmetry between escaping a state of means-ends incoherence by giving up the instrumental belief and escaping it by giving up the end, while Sect. 3 is largely concerned with the asymmetry between escaping it by giving up an end and escaping it by intending the means. As I explain in Sect. 3, there are reasons for treating these two asymmetries separately.

This paper will not take a stand on the question of whether rational requirements are normative (either strongly normative in that we ought to comply with them, or weakly normative in that we have a reason to comply with them). Much discussion of the wide-scope interpretation of rational requirements has involved criticism of the combination of the wide-scope interpretation with the view that rational requirements are normative. See, for instance, Raz (2005) and Setiya (2007). Defenders of the wide-scope interpretation can avoid such criticism simply by holding that rational requirements are not normative. But the “asymmetry” objections considered here cannot be so easily disposed of, since they challenge the wide-scope interpretation itself, not its combination with the view that rational requirements are normative.

See Way (2009) for an interesting account of instrumental rationality supporting this formulation.

Other formulations are, of course, possible: one could formulate alternative versions of IR-Medium or IR-Narrow by, very roughly, switching the attitude(s) mentioned in the antecedent with those that are within the logical scope of “requires.” But I take it that these three formulations have a prima facie plausibility that those other formulations would lack.

See, for instance, Setiya (2007, p. 667).

Schroeder (2004, p. 346). See also Schroeder (2009, p. 227). Schroeder draws a distinction between subjective instrumental rationality, which is what we are concerned with here, and objective instrumental rationality, which is concerned not with what an agent believes are the necessary means to his ends, but what are in fact the necessary means to an agent’s ends. See Schroeder (2004, p. 338).

Bedke (2009, p. 687).

Others have drawn a distinction along these lines. See, for instance, Kolodny (2005, pp. 515–516).

Ross (1930, pp. 18–41).

See Raz (2005, pp. 14–15).

I am claiming that local requirements are analogous to prima facie duties in some respects. There may be other ways in which they are not analogous.

It won’t help to deflect this objection by noting, as we did above, that instrumental rationality is a local requirement in some ways analogous to a Rossian prima facie duty. Intuitively, the person who proceeds by dropping his instrumental belief in this case has violated no requirement of rationality, not even a local one.

Broome (2007b, p. 161). Broome’s official statement of the requirement, which admits of both a wide-scope and narrow-scope interpretation, reads as follows: “Krasia: Rationality requires of N that, if N believes that she herself ought to F, and if N believes that she herself will F if and only if she herself intends to F, then N intends to F.” My shortening this requirement for ease of expression has no bearing on the argument presented here.

For discussion of these last two requirements—which Niko Kolody has called the “core requirements” of rationality, labeled (C+) and (C−)—see Kolodny (2005, p. 524).

Kolodny (2005, p. 521).

This argument for K-Wide is presented in greater detail in Brunero (2010).

A similar example, used for a different purpose, can be found in Korsgaard (2009, p. 169).

Bratman (1999, pp. 87–88).

Ibid., p. 89.

Bratman (2007, p. 33).

It may be that the objector explicitly spells out the example so that Candice has no such self-governing policy as part of her psychology. If that’s the case, then I'm no longer inclined to think that she’s instrumentally irrational, though she may be criticizable on other grounds.

Bratman (1999, p. 88). Bratman also notes that these more general intentions would be supported by the same rationales he gives earlier in Intentions, Plans and Practical Reason for the having of more specific intentions (rationales concerning our need for coordination and our limited resources as deliberators), the consideration of which would take us too far afield here.

References

Bedke, M. S. (2009). The Iffiest oughts: A guise of reasons account of end-given conditionals. Ethics, 119, 672–698.

Bratman, M. (1999). Intentions plans and practical reason. Stanford: CSLI Publications.

Bratman, M. (2007). Reflection, planning, and temporally extended agency. In Structures of agency. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Broome, J. (2000). Normative requirements. In J. Dancy (Ed.), Normativity. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers.

Broome, J. (2002). Practical reasoning. In J. Bermúdez (Ed.), Reason and nature: Essays in the theory of rationality. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Broome, J. (2007a). Wide or narrow scope? Mind, 116, 359–370.

Broome, J. (2007b). Is rationality normative? Disputatio, 2, 161–178.

Brunero, J. (2010). The scope of rational requirements. Philosophical Quarterly, 60, 28–49.

Dancy, J. (2000). Practical reality. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Darwall, S. (1983). Impartial reason. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Greenspan, P. S. (1975). Conditional oughts and hypothetical imperatives. Journal of Philosophy, 72, 259–276.

Hill, T. (1973). The hypothetical imperative. Philosophical Review, 82, 429–450.

Kolodny, N. (2005). Why be rational? Mind, 114, 509–563.

Kolodny, N. (2007). State or process requirements? Mind, 116, 371–385.

Korsgaard, C. (2009). Self-constitution: agency, identity and integrity. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Raz, J. (2005). The myth of instrumental rationality. Journal of Ethics and Social Philosophy, 1, 1–28.

Ross, W. D. (1930). The right and the good. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Schroeder, M. (2004). The scope of instrumental reason. Philosophical Perspectives, 18, 337–364.

Schroeder, M. (2009). Means-ends coherence, stringency and subjective reasons. Philosophical Studies, 143, 223–248.

Setiya, K. (2007). Cognitivism about instrumental reason. Ethics, 117, 649–673.

Wallace, R. J. (2001). Normativity, commitment and instrumental reason. Philosophers’ Imprint, 1, 1–26.

Way, J. (2009). Defending the wide scope account of instrumental reason. Philosophical Studies, 147, 213–233.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Joseph Raz for helpful discussion of an earlier version of this paper, and to an anonymous Philosophical Studies referee for providing challenging and useful comments, which helped improve the paper a great deal.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Brunero, J. Instrumental rationality, symmetry and scope. Philos Stud 157, 125–140 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-010-9622-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-010-9622-0