- 1Psycho-Oncology Unit, Azienda USL – IRCCS di Reggio Emilia, Reggio Emilia, Italy

- 2Palliative Care Unit, Azienda USL – IRCCS di Reggio Emilia, Reggio Emilia, Italy

- 3Azienda Sanitaria dell’Alto Adige, Comprensorio Sanitario di Merano, Merano, Italy

- 4Local Network of Palliative Care, Azienda USL Modena, Modena, Italy

Introduction: Palliative care is an emotionally and spiritually high-demanding setting of care. The literature reports on the main issues in order to implement self-care, but there are no models for the organization of the training course. We described the structure of training on self-care and its effects for a Hospital Palliative Care Unit.

Method: We used action-research training experience based mostly on qualitative data. Thematic analysis of data on open-ended questions, researcher’s field notes, oral and written feedback from the trainer and the participants on training outcomes and satisfaction questionnaires were used.

Results: Four major themes emerged: (1) “Professional role and personal feelings”; (2) “Inside and outside the team”; (3) “Do I listen to my emotions in the care relationship?”; (4) “Death: theirs vs. mine.” According to participants’ point of view and researchers’ observations, the training course resulted in ameliorative adjustments of the program; improved skills in self-awareness of own’s emotions and sharing of perceived emotional burden; practicing “compassionate presence” with patients; shared language to address previously uncharted aspects of coping; allowing for continuity of the skills learned; translation of the language learned into daily clinical practices through specific facilitation; a structured staff’s support system for emotional experiences.

Discussion: Self-care is an important enabler for the care of others. The core of our intervention was to encourage a meta-perspective in which the trainees developed greater perspicacity pertaining to their professional role in the working alliance and also recognizing the contribution of their personal emotions to impasse experienced with patients.

Introduction

Palliative care (PC) is an emotionally and spiritually high-demanding setting of care. Professionals working in the landscape of death are frequently exposed to existential issues, psychological challenges, and emotional distress associated with care at the end of life (Cole and Carlin, 2009; Sinclair, 2011). The risks of working in this context are well documented, e.g., burnout, compassion fatigue, and poor quality of care (Cole and Carlin, 2009; Sinclair, 2011; Peters et al., 2012). Self-care is an important enabler for the care of others (Kearney et al., 2009). The healthcare professionals (HCPs) must take care of their own health and well-being to support their competence in caring for patients (Mount et al., 2007; Kearney et al., 2009; Zulman et al., 2020).

The training in self-reflection of one’s emotional experience and its meanings associated with suffering, death and dying asks the HCPs to focus on their own resources and coping mechanisms (Meier et al., 2001; Kearney et al., 2009). It might result in better outcomes for both HCPs and the patients and their families (Meier et al., 2001; Kearney et al., 2009; Childers and Arnold, 2019). Research on the training of self-care, self-awareness of one’s emotions, spirituality and inner life of the HCPs, according to available resources and local context on these topics, is still needed.

Many international documents reported that the PC training in self-care skills might be relevant for the HCPs’ well-being and for the patients (Jünger et al., 2010; Jünger and Payne, 2011; Società Italiana di Cure Palliative, 2016; Brighton et al., 2019; Joint Royal Colleges of Physicians Training Board, 2020).

The Italian core curricula was developed from Italian Association of PC containing indications on “self-care and awareness” (Società Italiana di Cure Palliative, 2016). It suggests that the HCPs should have access to a space in which to reflect on one’s emotional experiences that are associated with the assistance of suffering and dying patients. It emphasized the relevance of having a high level of awareness of one own’s emotions, prejudices, projections, beliefs, and level of stress. It also suggests developing these skills with active educational strategies as role playing, and creating occasions of team discussions and opportunities for personal spiritual reflection during work time.

The European Association of PC white paper on spiritual care education (Best et al., 2020) suggests developing reflective capacity of staff: “Self-awareness can help the healthcare practitioner to avoid being distracted by their own fears, prejudices and restraints and attend to the patient.” Furthermore, Puchalski et al. (2019) suggested that learners should reflect on their own spirituality in practicing compassionate presence, on their professional call to serve, and on their spiritual beliefs and self-care practices. Clinicians can apply a compassionate presence, reflective listening, referral to dignity therapy, forgiveness therapy, and self-care spiritual practice (e.g., meditation and yoga) through case-based presentation.

Nonetheless, there is no one-size-fits-all solution as indicated by the scientific literature. All the previously referenced literature report on the main issues to be addressed in order to implement self-care and self-awareness of emotions, but the organization of the training courses (e.g., How many hours and days? What themes? What professional figures should be involved? Which setting: indoor or outdoor?) is an aspect in which there are no univocal models. Considering that inner life is a highly cultural-sensitive topic, it might be important in every context to coherently develop its own answer.

Therefore, we considered it imperative to describe a training experience on self-care to identify the specific characteristics of the topics covered, the number of hours identified, and the professionals involved.

Aim

We described the structure of a training on self-care and its effects for a Hospital Palliative Care Unit.

Methods

Setting

This study was conducted with a Specialized Palliative Care Service (SPCS) at an Italian hospital, in the context of continuous medical education, from September 2018 to April 2019. The SPCS is a specialized unit with no designated hospital beds. It was established in April 2013 with a remit of specialist in-hospital consultations and in a clinic for oncological and non-oncological outpatients and their family members. It is continuously involved in its own medical education and training courses to improve spiritual and psycho-social care, as well as courses to solve ethical dilemma (De Panfilis et al., 2020).

The SPCS includes three senior PC physicians and two advanced practice nurses. A psychologist psychotherapist expert in palliative care is also available for the care of patients and family members with severe psychological distress.

Subjects and Recruitment

We used a purposive sample by enrolling the entire staff of the SPCS in the training that consisted of three PC physicians (ST, SS, and SA), one resident doctor (ET), and two nurses (CA and EB).

Research Design

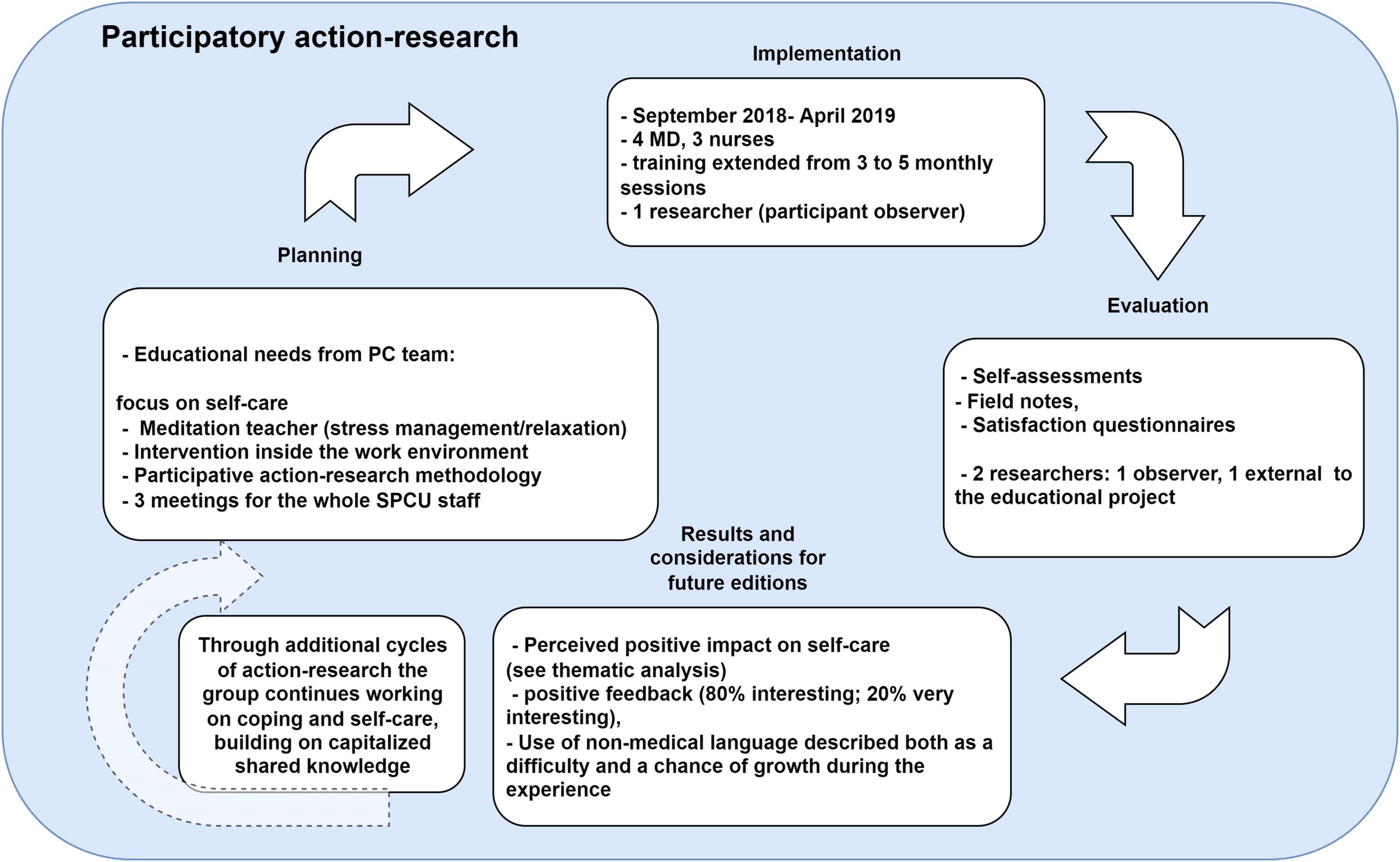

The research design was a participatory action-research of a training experience (Smith et al., 2010). An action-research approach in PC has been suggested as a possible way to both address an existing problem in a specific context and produce useful scientific knowledge by different authors (Hockley and Froggatt, 2006; Froggatt and Hockley, 2011; Hockley and Stacpoole, 2014). Our research was a “professionalizing type” action research, according to Hockley and Froggatt (2006), and the educational purpose was to “enhance professional control and individual ability to control work situation” (Smith et al., 2010; Hockley and Stacpoole, 2014). In this specific type of study design, the research was meant to be the response to a problem “defined by professional group” and “related to a behavior of practitioners,” as it was considered “successful” relatively to a contested definition of success (Smith et al., 2010; Hockley and Stacpoole, 2014). “Observation” as a research methodology can be “participative” or “non-participative,” depending on the choice and the possibilities of the researcher of taking part in the actions that he/she is also observing, which usually results in the production of field notes. Field notes were taken at a short distance from the events and iteratively enriched with additional reflections and insights of the researcher, so that he/she can get to a “thick description” of the observed phenomena. A participatory project usually allows for the elaboration of ad hoc instruments used to investigate preferences and choices of the participants.

In our study, field notes have been taken in different moments during both participative and non-participative observation by one researcher (LB). A second researcher (GM) facilitated the participative evaluation of the events with trainer and trainees (see Figure 1).

During the usual assessment of educational needs, aimed at the programming of the continuous education plan for the following months, the need to develop a training program on the topic of personal perspective and relation of the professionals with death, and the impact of this on their work life, emerged. LB who works as a psychologist psychotherapist with the SPCS, identified the trainer based on the routine educational needs assessment, which takes place during dedicated meetings where every participant can propose topics for the future training. The researcher (LB) maintained the role of note-taking and documentation during and after the training (see Figure 1).

Self-care and self-awareness of one’s own emotions were selected as the main focuses of the training. Consequently, the principal study question of the action-research was as follows:

“How can we develop an educational answer to our need of better coping with the strong emotional distress due to our constant relation with death in the professional environment of a palliative care unit?”

A secondary study question, according to the action-research methodology was as follows:

“Which useful lessons can we draw from our educational experience in the development of similar initiatives?”

Intervention

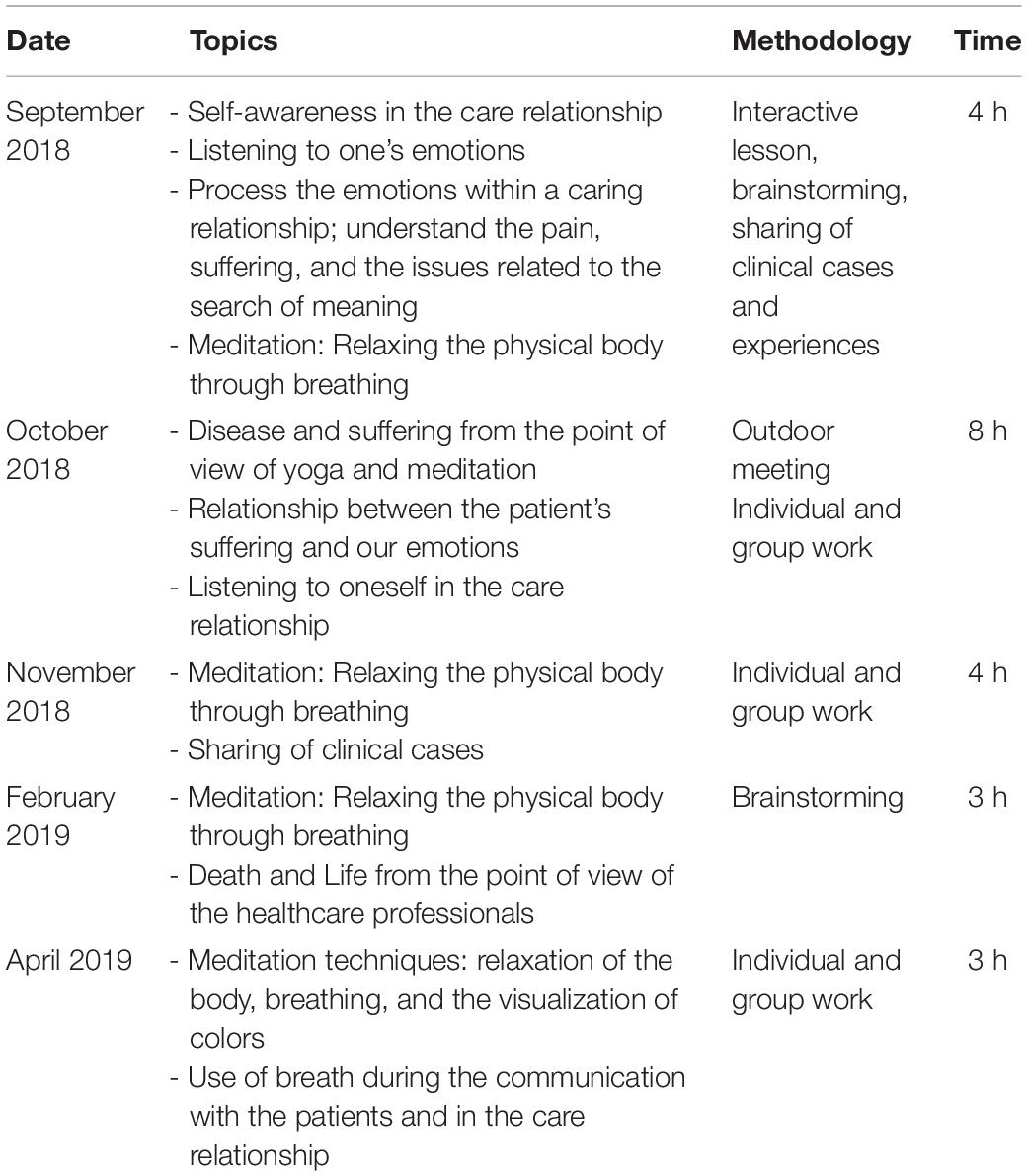

In accordance with internal procedures, the intervention was endorsed by the competent body of the Hospital (CME Scientific Committee): 30.4 CME were recognized. A trainer with a background in the field of non-technical skills related to the self-awareness of one’s own emotions was chosen. She is a meditation teacher with specific expertise in stress management and relaxation. The training was provided in three sessions for a total of 16 h (September 2018–December 2018). After three meetings, the trainees expressed a need to extend the training by an additional two meetings for a total of 6 h (February 2019–April 2019). They expressed the difficulties of understanding a language more focused on self-awareness of personal emotions.

The meetings started from significant clinical cases brought in by the participants with the focus on diseases, suffering, listening to one’s emotions starting from psycho-physical relaxation, and self-reflection on one’s response mechanism to suffering (see Table 1 for curricular details for each session). A training particularly based on a constructivist approach that “values the cultivation of trainee self-reflection, relational awareness, and creativity in envisioning alternative therapeutic strategies,” was used (Novack et al., 1997; Neimeyer et al., 2016). It supported the trainees to take the lead in analyzing and deconstructing their own in-session behaviors from a stance of self-awareness rather than self-criticism. Albeit demanding, the recursive and reflexive nature of the questions that scaffolded the training seemed to consistently help trainees shift to a meta-perspective in which they developed greater perspicacity for their role in the working alliance without seldom recognition of the contribution of their personal preoccupations or insecurities to impasse experienced in the care relationship (Neimeyer et al., 2016).

During the intervention and after its conclusion, the researchers (LB and GM) conducted sessions of training analysis and reflection on the impact, starting from the collected materials (answers to evaluation questions and field notes) to the subsequent participative meetings aimed at evaluating and reflecting on the results with trainers and participants (see Figure 1). In particular, as specified in Figure 1, LB supervised the self-assessment of the perceived educational needs of the group, and all the training was based on an inductive approach, where the participants were invited to share their experiences and personal emotions relevant in their daily activity as a starting point for the session. In the following year, LB facilitated a reflective attitude on what emerged, taking notes on spontaneous reflections on the training and using open ended questions to keep track of the considerations of the team on the contents and the strategies that they learnt in the training. To increase the trustworthiness of the analysis and the reflexivity of the group, GM examined all the data as an independent, external researcher and facilitated two sessions of reflections on the draft version results in the draft version.

Data Collection and Analysis

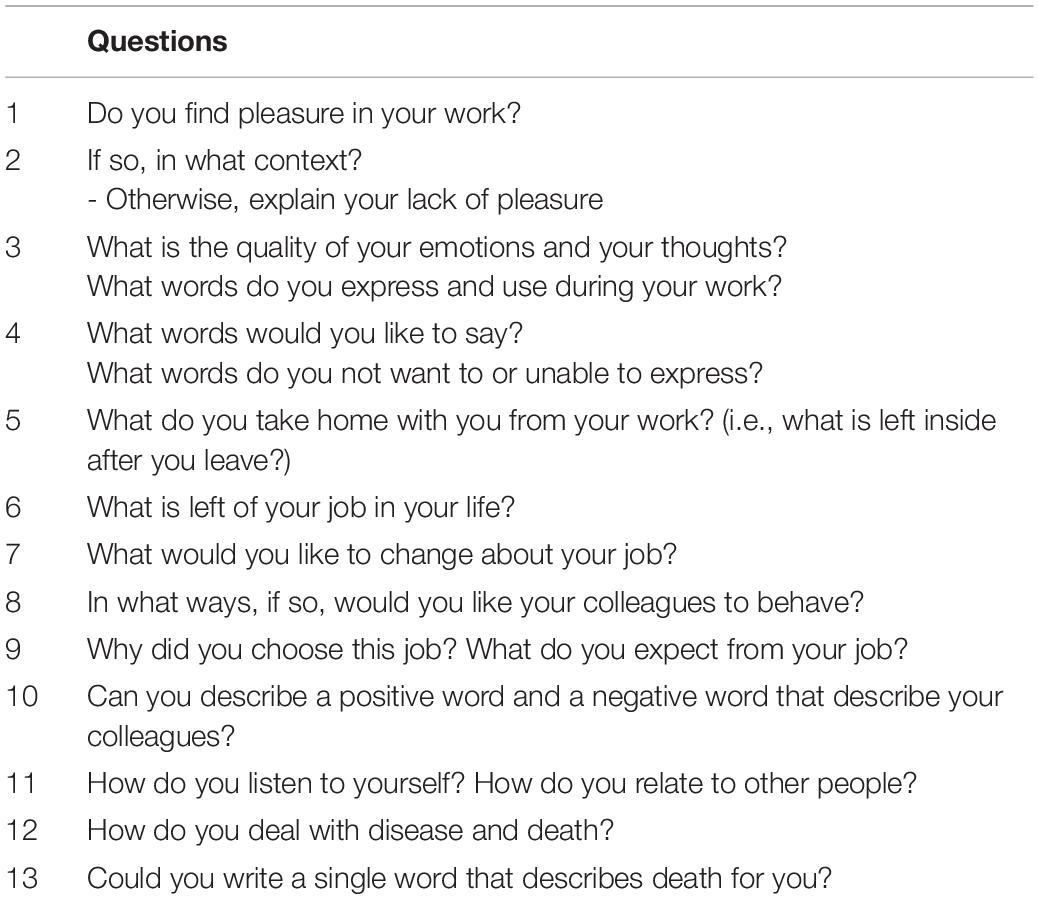

The researchers (LB and GM) administered both a pre-and post-training with an assessment test of open-ended questions. It consisted of 13 questions anonymously investigating the relationship of death and the ability of listening to one’s own needs and emotions, based on the literature from these topics (Novack et al., 1997) (see Table 2 for the contents of the questions).

Table 2. Pre- and post-training open-ended questions assessment test (Novack et al., 1997).

The researchers (LB and GM) conducted a thematic qualitative analysis (Elliott et al., 1999; Braun and Clarke, 2006; Gale et al., 2013; Hsieh and Shannon, 2016) of all materials (pre- and post-tests integrated with the field notes).

To generate initial codes, they independently labeled the texts and met to discuss them after. As the first step, the creation of categories and themes was developed with a “paper and pencil” approach. After themes emerged in the final shared list, researchers sorted and ordered data in charts using ATLAS qualitative analysis software. Subsequently, labels were combined to search for themes and sub-themes, comparing possible differences in the researchers’ points of view. Both had assigned tags to the text through a recursive and iterative process of deduction and induction until they were able to select the most relevant themes and sub-themes (Elliott et al., 1999; Hsieh and Shannon, 2016).

Afterward, the themes were reviewed and refined to assure their internal coherence. As such, a consensus among the researchers was reached in defining and naming the themes. Researchers identified as many themes as possible to accurately represent the content of the complete data set, and the findings were described through a thematic description, in order to explain the meaning of the most predominant and relevant themes (Hsieh and Shannon, 2016).

The resulting core themes were discussed with all trainees (Braun and Clarke, 2006; Gale et al., 2013) in a reflective session after the conclusion of the formal training with the purpose of gaining their opinion on the results and adding relevant information to the results.

Ethical Considerations

Because the study addressed educational practices and quality improvement, the hospital’s Internal regulation on the competent body of the Hospital (CME Scientific Committee) did not require specific informed consent procedures. Nevertheless, all participant information was handled as confidential, and informed participant’s consent was verbally gathered throughout. As the participation in the training implied involvement in the study, teacher made sure that participants were fully aware of this.

Results

Thematic Analysis

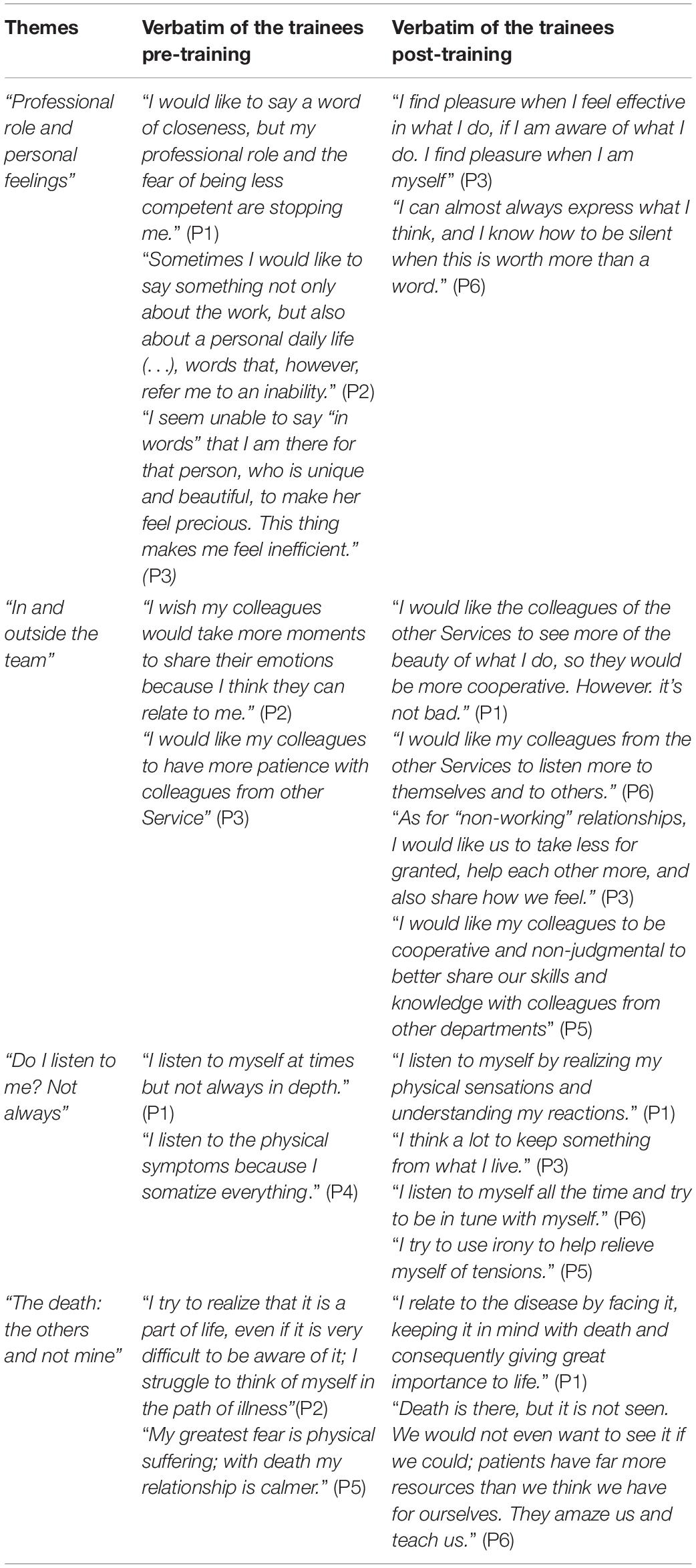

Four major themes emerged from the notes taken by the two researchers (LB and GM) and the pre-and post-tests: (1) “Professional role and personal feelings”; (2) “Inside and outside the team”; (3) “Do I listen to my emotions in the care relationship?”; (4) “Death: theirs vs. mine (see Table 3 for the major theme exemplars pre-test and post-test).”

(1) “Professional role and personal feelings”

During the pre-test, the participants expressed the need to say “words of proximity” to patients. However, they also expressed a fear of being perceived as less competent inside and outside of the professional role. The fear that the patient could leave also emerged, and this emotional component was perceived as inadequate.

“Sometimes I would like to say something not only about the work, but also about a personal daily life (…), words that, however, refer me to an inability” (P2).

According to the post-test, the discrepancy between professional role and personal identity seemed to decrease. Furthermore, a greater awareness of presence in the care relationship and the recognition of its quality emerged.

“I find pleasure when I feel effective in what I do, if I am aware of what I do. I find pleasure when I am myself” (P3).

At the end of the training, the trainees used phrases centered more on the feeling of an increased “lightness” regarding their emotional burden, based on the research’s file notes during the team meetings (LB). During the meetings the trainees focused more on their emotions by recognizing and expressing them as well as talking about their difficulties in the relationship.

(2) “Inside and outside the team”

According to the pre-test, a distinction between the team colleagues and colleagues from the other services of the hospital developed due to the participants’ expectations of greater collaboration from their colleagues from other units.

“I would like my colleagues to have more patience with colleagues from other Service” (P3).

At the end of the course, a greater understanding toward colleagues outside the team was reported in the evaluation forms and team meetings.

“I would like the colleagues of the other Services to see more of the beauty of what I do, so they would be more cooperative. However, it’s not bad” (P1).

The trainees also reported more interest in the emotional experience of colleagues from their own and other services, according to the field notes of the researcher (LB).

(3) “Do I listen my own emotions in the care relationship?”

During the pre-test, sporadic listening was reported, regarding one’s own emotions.

Some participants reported developing the habit of listening more to themselves during and after the medical visits, starting from physical symptoms and others carving out an individual inner space.

“I listen to myself at times but not always in depth” (P1).

At the end of the training, there was a greater emphasis in listening to oneself and motivation to share one’s emotional states with colleagues.

“I listen to myself by realizing my physical sensations and understanding my reactions” (P1).

(4) “Death: theirs vs. mine”

According to the pre-test, death was recognized as present in the care relationship, even when it is not named.

“I try to realize that it is part of life, even if it is very difficult to be aware of it; I struggle to think of myself in the path of illness” (P2).

At the end of the training, the participants recognized the death of the patients as well as their own, as seen from the thematic analysis.

“I relate to the disease by facing it, keeping it in mind with death and consequently giving great importance to life” (P1).

In reference to the research field notes (LB), the importance of dealing with death by talking about dignity, in particular in reference to the Model of Chochinov (2002), and part of the team’s background was revealed.

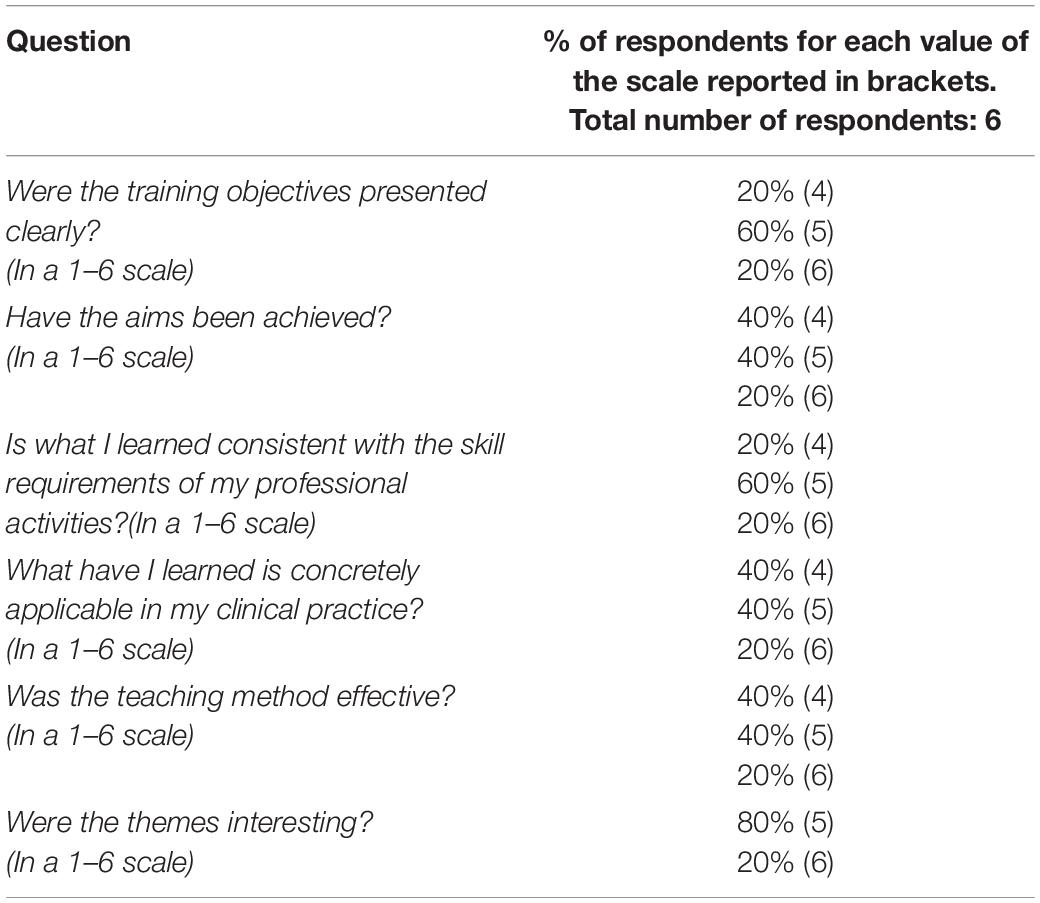

Table 4 shows the results of the satisfaction questionnaires after the intervention. In general, the trainees found the themes of the training interesting (80% interesting; 20% very interesting), however, from the field notes difficulties became evident regarding the language used which, having been not technical, because the trainer does not work in the hospital setting.

Discussion

Self-care is an important enabler to the care of others. In our study, the meditation teacher was chosen with the aim to improve self-awareness of emotions in the care relationship and to foster self-care, starting from body relaxation and use of meditation techniques.

Our study identified a methodology in the action-research to improve a training program with satisfaction and qualitative evidence of the impact on the palliative practice. The participants identified oral and written feedback from the trainer and the researchers (LB and GM) during and after the training, as a method to improve the course contents. The researcher’s field notes taken during and after the training have been deemed as useful to customize the teaching (see Figure 1). Due to the increasing need in field of self-care, the action-research may be an effective way of developing programs to have a real impact on a professional’s practice in accordance with available resources.

HCPs discussed meaningful experiences with patients, listening to themselves in a broader concept of “learning to learn” (Bateson, 1997) from self-awareness of own emotions rather than self-criticism, as suggested by a constructivist and self-compassion approach (Petrocchi et al., 2014; Neimeyer et al., 2016; Neff et al., 2020). At the end of the training, there was a greater emphasis in listening to oneself and motivation to share one’s emotional states with colleagues, supported by a self-compassion approach. This approach involves responding kindly to one’s own suffering and failures, rather than neglecting one’s well-being or engaging in judgment and self-criticism (Petrocchi et al., 2014; Neff et al., 2020), according to the field notes of the researcher (LB). The oral and written feedback from participants revealed important changes developed during the team meetings, such as greater attention was given to one’s emotional experience during the discussion of clinical cases. Phrases like “This patient is…” and “These families are…” were changed to “My difficulty was…,” “I felt that way,” and “I ask the team for help,” as reported in the research’s files notes (LB). Some authors underlined that effective self-care practice involves self-awareness, self-compassion, and the implementation of a variety of strategies across inner life domains (Mills et al., 2020; Moroni et al., 2020). Greater awareness of the ability to cultivate positive emotions such as self-compassion should be promote as a part of self-care practice, as reported in a systematic integrative review on self-compassion in hospice and PC (Garcia et al., 2021).

At the end of the training, the participants also reported more interest in the emotional experience of colleagues from their own and other services. A qualitative study that explored the meaning and practice of self-care in PC HCPs, reported that self-compassion was considered essential for self-care and related to compassion for others, as our study suggested (Mills et al., 2018). In particular, treating oneself with kindness, awareness of common humanity, and avoiding over identification with emotions can contribute to the personal well-being of hospice and PC HCPs (Garcia et al., 2021). The trainees actively applied these principles that also emerged from the Dignity Model (Buonaccorso et al., 2021; Tanzi and Buonaccorso, 2021). The lesson learned from the training course applied to the pandemic was that having a compassionate presence during the short visits to isolated COVID-19 patients at the Infectious Disease Unit helped to restore an increased perception of dignity and humanity (Tanzi et al., 2020; Tanzi and Buonaccorso, 2021). Solitary death in the extraordinary emergency that HCPs have experienced has required increased skills and closeness to these patients, in terms of compassion and conscious presence (Moroni et al., 2020). The compassionate support, self-care, and quality of life are also important concerns for the HCPs (Adams et al., 2020; Mills et al., 2020). Prioritizing self-care by developing a plan is an effective strategy that can be supported by a specific intervention as Self-Care Matters, a free resource available online1. It is drawn from contemporary research to shed light on understanding, practicing, and planning self-care through the voice of experienced clinicians (Palliative Care Australia, 2020).

Individual self-care plans in combination with Staff Supportive initiatives are indicated as practice to prioritize in such emergencies (Mills et al., 2015, 2018; Sansó et al., 2015). As reported in a cross-sectional online survey of PC Spanish professionals, the cultivation of inner life for better professional quality of life and compassionate care, and its repercussion on professionals’ wellbeing, take place across sex, age, and controlling for important work variables, such as work overload or workload control. When compared to these traditional organizational variables, self-compassion and coping with death have stronger effects on professional quality of life, which emphasizes the importance of properly cultivating an inner life in HCPs to provide compassionate care (Galiana et al., 2021).

Through the training, the our team began to reflect on a self-care plan as a team that considered personal needs in the context of PC. For the incoming year two training on “spirituality” and “compassion and self-compassion” were organized with spiritual assistants and psychotherapists who work in hospice and PC to reflect on their own spirituality and compassionate presence as HCPs.

Useful Tips for Future Editions

Reflective sessions with the participants highlighted some possible improvements of the initial program, useful for future editions of similar initiatives in their context or in similar environments. In our experience, it was useful to keep an open discussion with the participant on the right number of sessions. In fact, while three meetings were initially planned, the group decided to extend the training to five meetings total, to give participants the time to learn meditative techniques within specific PC context and to get more familiar with a new language related to non-medical disciplines. As a result, in our model we developed a solution of five meetings of 4 h, monthly.

Furthermore, one session was conducted outdoor, to facilitate the learning of physical body relaxation and meditation techniques.

The core of our intervention was to encourage a meta-perspective in which the trainees developed greater perspicacity pertaining to their professional role in the working alliance and also recognizing the contribution of their personal emotions to impasse experienced with patients. In our experience, the trainees reported the importance of identifying a trainer who carries out at least part of his activity within a context of patient care. This, from our experience, would make it easier to use a “common” language. The limit of identifying trainers outside the CP setting could be linked to the fact of using techniques that belong to other traditions (Buddhist, Tibetan…) without, however, integrating them with Western culture and in the context of PC. The oral and written feedback from participants revealed the importance of having a dedicated operator who already works with the team and who is able to translate the language learned during the training into daily clinical practices. In our study, this work of continuing the learned contents was facilitated during the following team meetings in which the operator (LB) participated in her usual role as supporting psychologist.

Coping with death and awareness are important predictors of quality of life, being positively related to Compassion Satisfaction (Galiana et al., 2021; Garcia et al., 2021). In the increasingly needed field of self-awareness, a more participatory format, like the action-research design, may be an effective way of improving programs to have a real impact on professionals’ practice in accordance with available resources and local context’s needs. This methodology allows to better tailor the educational experience, especially considering that the language used to speak about self-awareness can be difficult to develop.

Limitations

Regarding limitations, we highlight that our sample size of six participants was small. This was due to the type of intervention in that only the working staff of the interested unit was necessary to be involved to build a more tailored training experience. However, our study is a qualitative research/data analysis that is not intended to generalize the results. In this way, we wanted to propose an experience to contribute to advancing knowledge in an area of increasing importance in PC—self-care as a method to cope with suffering and death.

Furthermore, the SPCS had already participated in other courses on bioethics, psychological skills, and spirituality. Therefore, the training was aimed at HCPs previously trained on similar topics. Finally, the presence of a competent figure as a psychologist who gives continuity to the contents after the course and helps the team to translate them into practice might be a great facilitator for learning, but local resources do not always allow the continuous presence of a psychologist.

While this qualitative reporting of an impactful experience may help in developing similar and useful experiences, we acknowledge that only different and more quantitative types of researchers could help to understand the optimal elements and combined impact of staff support and self-care and the method that these can be best implemented in normal circumstances and also adjusted to respond to situations of heightened stress or complexity (Sansó et al., 2015; Adams et al., 2020).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Ethics Statement

Ethical approval was not provided for this study on human participants because the study addressed educational practices and quality improvement, consequently the hospital’s Internal regulation on the competent body of the Hospital (CME Scientific Committee) did not require specific informed consent procedures. Ethical review and approval was not required for this study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Nevertheless, all participant information was handled as confidential, and informed participant’s consent was verbally gathered throughout. As the participation in the training implied involvement in the study, teacher made sure that participants were fully aware of this. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author Contributions

LB analyzed the literature, contributed to the conception of the study, the draft of the manuscript, and critical revision with relevant theoretical content, supporting each member of the team and approved the final version to be submitted and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of it are appropriately investigated and resolved. ST analyzed the literature, contributed to the draft of the manuscript and to its critical revision, together with SS, SA, CA, EB, and ET took part to the training and provided iterative feedback, decisions on focus and structure of the training, evaluation of perceived outcomes, and the role of co-researchers as typical of a participatory action research. GM analyzed the literature and gave a methodological contribution, in particular on qualitative methods and contributed to the conception of the study, to the draft of the manuscript, and to its critical revision and approved the final version to be submitted and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of it are appropriately investigated and resolved. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

Anna Grazia Fiorani as a teacher of the intervention.

Footnotes

References

Adams, M., Chase, J., Doyle, C., and Jason, M. (2020). Self-care planning supports clinical care: putting total care into practice. Prog. Palliat. Care 28:5, 305–307. doi: 10.1080/09699260.2020.1799815

Best, M., Leget, C., Goodhead, A., and Paal, P. (2020). An EAPC white paper on multi-disciplinary edu-cation for spiritual care in palliative care. BMC Palliative Care 19:9. doi: 10.1186/s12904-019-0508-4

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualit. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Brighton, L. J., Selman, L. E., Bristowe, K., Edwards, B., Koffman, J., and Evans, C. J. (2019). Emotional labour in palliative and end-of-life care communication: a qualitative study with generalist palliative care providers. Patient Educ. Counseling 102, 494–502. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2018.10.013

Buonaccorso, L., Tanzi, S., De Panfilis, L., Ghirotto, L., Autelitano, C., Chochinov, H. M., et al. (2021). Meanings emerging from dignity therapy amongst cancer patients. J. Pain Symp. Manage. [Epub ahead of print]. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2021.02.028

Childers, J., and Arnold, B. (2019). The inner lives of doctors: physician emotion in the care of the seriously Ill. Am. J. Bio. 19, 29–34. doi: 10.1080/15265161.2019.1674409

Chochinov, H. M. (2002). Dignity-conserving care–a new model for palliative care: helping the patient feel valued. JAMA 287, 2253–2260. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.17.2253

Cole, T. R., and Carlin, N. (2009). The suffering of physicians. Lancet 374, 1414–1415. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(09)61851-1

De Panfilis, L., Tanzi, S., Perin, M., Turola, E., and Artioli, G. (2020). “Teach for ethics in palliative care”: a mixed-method evaluation of a medical ethics training programme. BMC Palliative Care 19:149. doi: 10.1186/s12904-020-00653-7

Elliott, R., Fischer, C. T., and Rennie, D. L. (1999). Evolving guidelines for publication of qualitative research studies in psychology and related fields. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 38, 215–229. doi: 10.1348/014466599162782

Froggatt, K., and Hockley, J. (2011). Action research in palliative care: defining an evaluation methodology. Palliative Med. 25, 782–787. doi: 10.1177/0269216311420483

Gale, N. K., Heath, G., Cameron, E., Rashid, S., and Redwood, S. (2013). Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 13:117. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-13-117

Galiana, L., Sansó, N., Martínez, I. M., Vidal-Blanco, G., Oliver, A., and Larkin, P. J. (2021). Palliative care professionals’ inner life: exploring the mediating role of self-compassion in the prediction of compassion satis-faction, compassion fatigue, burnout and wellbeing. J. Pain Symp. Manage. 63, 112–123. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2021.07.004

Garcia, A. C. M., Silva, B. D., da Silva, L. C. O., and Mill, J. (2021). Self-compassion in hospice and palliative care. J. Hospice Palliative Nur. 23, 145–154. doi: 10.1097/NJH.0000000000000727

Hockley, J., and Froggatt, K. (2006). The development of palliative care knowledge in care homes for older people: the place of action research. Palliative Med. 20, 835–843. doi: 10.1177/0269216306073111

Hockley, J., and Stacpoole, M. (2014). The use of action research as a methodology in healthcare research. Eur. J. Palliative Care 21, 110–114.

Hsieh, H. F., and Shannon, S. E. (2016). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualit. Health Res. 15, 1277–1288.

Joint Royal Colleges of Physicians Training Board (2020). Specialty Training Curriculum for Palliative Medicine. Available online at: https://www.jrcptb.org.uk/sites/default/files/Pall%20Med%20Curriculum%202022%20v20%20for%20consultation%20Sept%2019.pdf

Jünger, S., and Payne, S. (2011). Guidance on postgraduate education for psychologists involved in palliative care. Eur. J. Palliative Care 18, 238–252.

Jünger, S., Payne, S., Costantini, A., Kalus, C., and Werth, J. L. (2010). The EAPC TASK Force on education for psychologists in palliative care. Eur. J. Palliative Care 17, 84–87.

Kearney, M. K., Weininger, R. B., Vachon, M. L. S., Harrison, R. L., and Mount, B. M. (2009). Self-care of physicians caring for patients at the end of life. being connected a key to my survival. JAMA 301, 155–164. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.352

Meier, D. E., Back, A. L., and Morrison, R. S. (2001). The inner life of physicians and care of the seriously ill. JAMA 286, 3007–3014. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.23.3007

Mills, J., Ramachenderan, J., Chapman, M., Greenland, R., and Agar, M. (2020). Prioritising workforce wellbeing and resilience: what COVID-19 is reminding us about self-care and staff support. Palliative Med. 34, 1137–1139. doi: 10.1177/0269216320947966

Mills, J., Wand, T., and Fraser, J. A. (2015). On self-compassion and self-care in nursing: selfish or essential for compassionate care? Int. J. Nur. Study 52, 791–793. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2014.10.009

Mills, J., Wand, T., and Fraser, J. A. (2018). Exploring the meaning and practice of self-care among palliative care nurses and doctors: a qualitative study. BMC Palliative Care 17:63. doi: 10.1186/s12904-018-0318-0

Moroni, M., Montanari, L., De Panfilis, L., Buonaccorso, L., and Tanzi, S. (2020). (Not) dying alone: recommendations from Italian palliative care during COVID-19 pandemic. Blog BMJ Supportive Palliative Care. Available online at: https://blogs.bmj.com/spcare/2020/06/23/not-dying-alone-recommendations-from-palliative-care-during-covid-19-pandemic/

Mount, B. M., Boston, P. H., and Cohen, S. R. (2007). Healing connections: on moving from suffer-ing to a sense of well-being. J. Pain Symp. Manage. 33, 372–388. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.09.014

Neff, K. D., Toth-Kiraly, I., Knoc, M. C., Kuchar, A., and Davidson, O. (2020). The developement and validation of the state self-compassion scale (long- and short form). Mindfulness 12, 121–140. doi: 10.1007/s12671-020-01505-4

Neimeyer, R. A., Woodward, M., Pickover, A., and Melissa, S. (2016). Questioning our questions: a constructivist technique for clinical supervision. J. Constr. Psychol. 29, 100–111. doi: 10.1080/10720537.2015.1038406

Novack, D., Suchman, A., Clark, W., Epstein, R. M., Najberg, E., and Kaplan, C. (1997). Calibrating the physician. personal aware-ness and effective patient care. working group on promoting physician personal awareness, american academy on physician and patient. JAMA 278, 502–509. doi: 10.1001/jama.278.6.502

Palliative Care Australia (2020). Self-Care Matters: A Self-Care Planning Tool. Canberra: Austral-ian Capital Territory: PCA.

Peters, L., Cant, R., Sellick, K., O’Connor, M., Lee, S., Burney, S., et al. (2012). Is work stress in palliative care nurses a cause for concern? A literature review. Int. J. Palliative Nur. 18, 561–567. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2012.18.11.561

Petrocchi, N., Ottaviani, C., and Couyoumdjian, A. (2014). Dimensionality of self-compassion: translation and construct of the self-compassion scale in an Italian sample. J. Mental Health 23, 72–77. doi: 10.3109/09638237.2013.841869

Puchalski, C., Jafari, N., Buller, H., Haythorn, T., Jacobs, C., and Ferrell, B. (2019). Interprofessional spiritual care education curriculum: a milestone toward the provision of spiritual care. J. Palliative Med. 23, 777–784. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2019.0375

Sansó, N., Galiana, L., Oliver, A., Pascual, A., Sinclair, S., and Benito, E. (2015). Palliative care professionals’ inner life: ex-ploring the relationships among awareness, self-care, and compassion satisfaction and fatigue, burnout, and coping with death. J. Pain Symp. Manage. 50, 200–207. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.02.013

Sinclair, S. (2011). Impact of death and dying on the personal lives and practices of palliative and hospice care professionals. Multicenter Study CMAJ 183, 180–187. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.100511

Smith, L., Rosenzweig, L., and Schmidt, M. (2010). Best practices in the reporting of participatory action research: embracing both the forest and the trees. Counseling Psychol. 38, 1115–1138. doi: 10.1177/0011000010376416

Società Italiana di Cure Palliative (2016). Available online at: https://www.sicp.it/?s=core+curriculum (accessed, 2021).

Tanzi, S., Alquati, S., Martucci, G., and De Panfilis, L. (2020). Learning a palliative care approach during the COVID-19 pandemic: a case study in an infectious diseases unit. Palliative Med. 34, 1220–1227. doi: 10.1177/0269216320947289

Tanzi, S., and Buonaccorso, L. (2021). Enhancing patient dignity: opportunities addressed by a specialized palliative care unit during the coronavirus pandemic. J. Palliative Med. 24:3. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2020.0661

Keywords: self-care, self-awareness, compassionate presence, palliative care (MeSH), continuous education, action-research

Citation: Buonaccorso L, Tanzi S, Sacchi S, Alquati S, Bertocchi E, Autelitano C, Taberna E and Martucci G (2022) Self-Care as a Method to Cope With Suffering and Death: A Participatory Action-Research Aimed at Quality Improvement. Front. Psychol. 13:769702. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.769702

Received: 02 September 2021; Accepted: 14 January 2022;

Published: 21 February 2022.

Edited by:

Yi-lang Tang, Emory University, United StatesReviewed by:

Riccardo Torta, University of Turin, ItalyJason Mills, University of the Sunshine Coast, Australia

Copyright © 2022 Buonaccorso, Tanzi, Sacchi, Alquati, Bertocchi, Autelitano, Taberna and Martucci. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Loredana Buonaccorso, loredana.buonaccorso@ausl.re.it

Loredana Buonaccorso

Loredana Buonaccorso Silvia Tanzi2

Silvia Tanzi2