No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

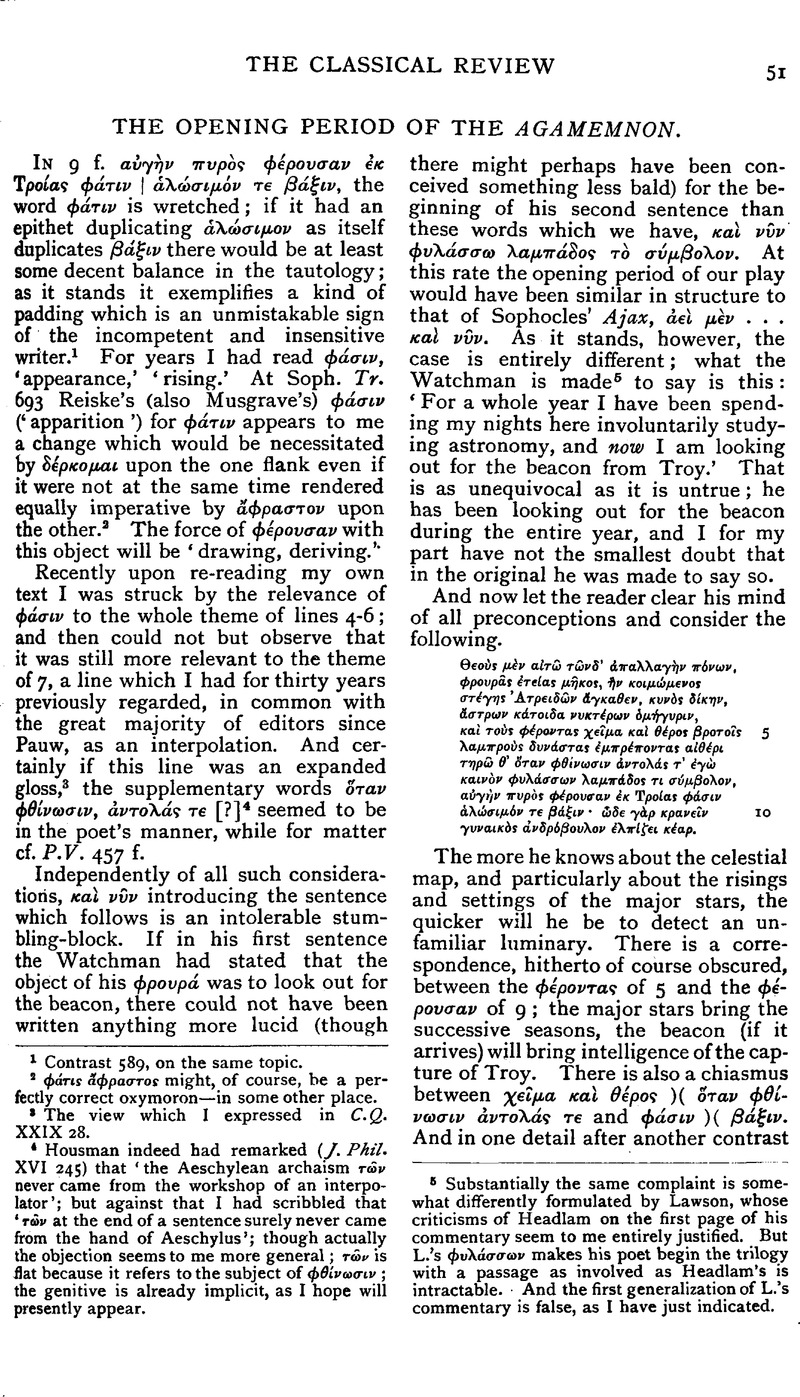

The Opening Period of the Agamemnon.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 October 2009

Abstract

- Type

- Review Article

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Classical Association 1936

References

page 51 note 1 Contrast 589, on the same topic.

page 51 note 2 φτις ἄφραστος might, of course, be perfectly correct oxymoron—in some other place.

page 51 note 3 The view which I expressed in C.Q. XXIX 28.

page 51 note 4 Housman indeed had remarked (J. Phil. XVI 245) that ‘the Aeschylean archaism τν never came from the workshop of an interpolator’; but against that I had scribbled that ‘τν at the end of a sentence surely never came from the hand of Aeschylus’; though actually the objection seems to me more general; τν is flat because it refers to the subject of φθνωσιν; the genitive is already implicit, as I hope will presently appear.

page 51 note 5 Substantially the same complaint is somewhat differently formulated by Lawson, whose criticisms of Headlam on the first page of his commentary seem to me entirely justified. But L.'s φνλσσων makes his poet begin the trilogy with a passage as involved as Headlam's is intractable. And the first generalization of L.'s commentary is false, as I have just indicated.

page 52 note 1 And when its appearance is described at 289 as a sunrise, παραντελασα Zakas ; on this and other points see my discussion in Annals of Archaeology and Anthropology XXII 111–127. (My 301a is now seen to be more appropriate than ever.)

page 53 note 1 At 67–71 they are confident, not about victory, but about the moral law. Moral absolutism does not justify confidence in any particular eventuality; see 1025–9.

page 53 note 2 The λαμπς is not (as I admit I at first supposed, keeping τ and putting a comma after φνλ 'σσων) another δυνστης; on the contrary, the stars also are σμβολα.

page 53 note 3 How could it? Let the reader diagnose the fallacy in L.'s fourth sentence.

page 53 note 4 ὅταν is not even resumptive, and Weil's fine sense of style is seen in his subsequent rejection even of his own improvement ἔχων … εὐτ' ἂν.

page 53 note 5 And even some who are not too sensitive as Aeschyleans; Wilamowitz printed his εὕδων; ‘correxi’—in spite, for instance, of 14.

page 53 note 6 Nor αε, as I previously thought, with Bentley's κοτην transferred to the place of εὐνν.

page 53 note 7 Klausen, Wunder, Paley, Wecklein, Headlam take the latter view.

page 53 note 8 As I rendered, Cambridge Review, January 27, 1922.

page 53 note 9 Someone may yet reply that this was Aeschylean piety.

page 53 note 10 Eur. Or. 72, cited by Wecklein, is different the period is indefinite, and there is a sting.

page 54 note 1 On whom see Wecklein Praef. p. xii.

page 54 note 2 ‘Verba φρονρς τεας μκος ![]() κ. multum molestiae interpretibus fecerunt: quibuscumque ea modis versaveris, nullam invenies explicationem, quae diligentius consideranti placitura sit’—Karsten, excellently as usual.

κ. multum molestiae interpretibus fecerunt: quibuscumque ea modis versaveris, nullam invenies explicationem, quae diligentius consideranti placitura sit’—Karsten, excellently as usual.

page 54 note 3 See e.g. L. and S.9 s. vv. γκς, γκλη I 1, γκαιζομαι.

page 54 note 4 If they said ‘take from the arms’ (assuming that the form existed, and presumably ἄγκαθεν: γκς = ἕκαθεν: κς) when they meant ‘take in the arms’, what did they say when they meant, as mothers and nurses daily and nightly did, take from the arms’? ‘Take in the arms’? Not Aeschylus, demonstrably.