Abstract

The complexity of current social and environmental grand challenges generates many conflicts and tensions at the individual, organization and/or systems levels. Paradox theory has emerged as a promising way to approach such a complexity of corporate sustainability going beyond the instrumental business-case perspective and achieving superior sustainability performance. However, the fuzziness in the empirical use of the concept of “paradox” and the absence of a systems perspective limits its potential. In this paper, we perform a systematic review and content analysis of the empirical literature related to paradox and sustainability, offering a useful guide for researchers who intend to adopt the concept of “paradox” empirically. Our analysis provides a comprehensive account of the uses of the construct - which allows the categorization of the literature into three distinct research streams: 1) paradoxical tensions, 2) paradoxical frame/thinking, and 3) paradoxical actions/strategies - and a comprehensive overview of the findings that emerge in each of the three. Further, by adopting a system perspective, we propose a theoretical framework that considers possible interconnections across the identified paradoxical meanings and different levels of analysis (individual, organizational, systems) and discuss key research gaps emerging. Finally, we reflect on the role a clear notion of paradox can have in supporting business ethics scholars in developing a more “immanent” evaluation of corporate sustainability, overcoming the current instrumental view.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The major social and environmental challenges of our time – such as climate change, biodiversity loss, modern slavery, and social inequality (Ferraro et al., 2015; Figge & Hahn, 2020; Whiteman et al., 2013) – are generating increasing pressure on social and environmental systems (Grewatsch et al., 2021). These challenges, which are commonly defined as wicked problems (Rittel & Webber, 1973), are characterized by complex dynamics resulting from the deep interconnections among the social, environmental, and economic elements involved, which often enter into contraposition and generate multiple tensions (Haffar & Searcy, 2017; Hahn et al., 2018; Pecl et al., 2017). Due to the more frequent consequences of extreme weather events, growing consumer pressure, and increasingly stringent regulations, companies increasingly need to address multiple demands that may conflict with each other—for example, economic stability versus required social/environmental goals—tensions are a tangible and unavoidable experience for companies that seriously deal with sustainability issues (Hahn et al., 2010). Thus, to address the complexity of such conflicts, a holistic and system-based perspective is needed (Ergene et al., 2020; Schad & Bansal, 2018; Whiteman et al., 2013).

The mainstream approach to sustainability in both research and practice, which is known as the business case (Hahn et al., 2014, 2018), has proved unfit for this purpose, as it considers social and environmental issues merely as means to increase the economic performance of companies (Ergene et al., 2020; Figge & Hahn, 2020). Indeed, the complexity of sustainability demands is making it clear to companies that these elements are a real challenge for their current and future stability, and for this reason cannot be put on the back burner or approached with a narrow focus on profitability, but have to be addressed in their own value and simultaneously with the core activities of the business. This instrumental approach to corporate sustainability is contested also within the business ethics literature, because it reduces social and environmental concerns to mere investments made for economic gain instead than contexts for ethical decision-making (Johnsen, 2021). Meanwhile, paradox theory is emerging as a promising alternative to investigate and frame the nature and management of corporate sustainability issues. In contrast to the business case approach, paradox theory considers social, environmental, and economic concerns as opposing yet interrelated elements that exist simultaneously and persist over time (Schad et al., 2016; Smith & Lewis, 2011), making it capable of overcoming the instrumental view of sustainability (Johnsen, 2021).

Despite the recent burgeoning of this literature, the potential of paradox theory in informing corporate sustainability research and practice is still limited, given the lack of clarity around the use and meaning of the concept of “paradox”. Paradox still appears as a “fuzzy concept”, which is defined as “one which possess[es] two or more alternative meanings and thus cannot be reliably identified or applied by different readers or scholars” (Markusen, 2003, p. 702). Indeed, the construct has been used to refer to divergent phenomena, making emerging findings difficult to compare (Cao et al., 2009) and leaving the implications of relevant studies unclear. Furthermore, its applications have failed to include a systems perspective, focusing instead only on the individual or organizational level of analysis. However, wicked problems, such as conflicts between economic, social, and environmental demands and goals, are characterized by multilayer connections between levels (Grewatsch et al., 2021; Williams et al., 2017); to effectively comprehend such tensions and implement actions capable of improving social and natural conditions, a systems perspective is needed (Bansal et al., 2020; Grewatsch et al., 2021; Schad & Bansal, 2018).

With this limitations in mind, this study proposes a framework for understanding the uses and meanings of paradox in corporate sustainability research, taking a systems perspective and with the aim to make this concept clearer and more effective for scholars, managers, and organizations. To achieve this result, we performed a systematic literature review and content analysis based on empirical publications that adopted paradox theory in addressing corporate sustainability issues. We identify three uses of the concept of paradox (i.e., detective, sensemaking, and responsive) and three connected meanings (i.e., paradoxical tensions, paradoxical frame/thinking, and paradoxical actions/strategies), which allow us to categorize the existing literature into three distinct research streams. Furthermore, we provide a map of the existing research gaps, adopting a systems perspective and discussing its implications for business ethics research.

The contributions of this study are threefold. First, we contribute to paradox and sustainability literature (Hahn et al., 2018) by disentangling the different meanings the concept has assumed to study sustainability tensions. Accordingly, we propose a thematic map that categorizes the literature into three distinct (but not isolated) research streams; representing a useful guide for researchers and practitioners who intend to take stock of existing knowledge and identify future research opportunities. By addressing the lack of clarity in its empirical use, we reduce the fuzziness of the paradox concept and thus support developing its potential as a construct for framing corporate sustainability. Second, in line with Williams et al. (2017) and Schad and Bansal (2018), we provide a theoretical framework that can be used to understand the role of paradox in sustainability; taking a systems approach and accounting for the interconnections that can occur across meanings of paradox and across levels of analysis (i.e., individuals, organizations, and systems). We also suggest directions for future research spotting key research gaps in the relevant literature. Accordingly we aim at enabling scholars to better investigate and understand the complex nature of corporate sustainability issues and provide a broader impact. Finally, by highlighting future research opportunities related to the intersection between the concept of paradox and business ethics literature, we contribute to business ethics research by suggesting how paradox theory can be used to support the development of a more “immanent” evaluation of sustainability, one that challenges the normative principles of the instrumental approach and that values what can be done by business actors when there is no a priori knowledge about what forms of sustainability are possible (Johnsen, 2021). While corporate social responsibility (CSR) and sustainability have long been central topics in business ethics discussions (Calabretta et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2019; Robertson, 2008), our framework allows to identify how paradox theory can support business ethics scholars in “deepen[ing] [their] engagement with the social to understand, evaluate and guide action in dialogue with society” (Islam & Greenwood, 2021, p. 1) in front of the today's pressing social and environmental grand challenges.

Theoretical Background

The Concept of Paradox

The concept of paradox in management research dates back in the late 1970s and 1980s; as it started to be suggested as a proper lens for investigating organizational phenomena (see Carmine & Smith, 2021; Schad et al., 2016). The theoretical underpinnings for the development of this new lens were philosophers and political scientists, such as Hegel, Marx, and Engels (Benson, 1977), especially their work on dialectics (Hargrave & Van de Ven, 2017); communication authors and sociologists, such as Taylor, Bateson, and Watzlawick (Putnam, 1986); and psychodynamic scholars, such as Jung, Adler, Frankel, and Freud (Smith & Berg, 1987). More recently, Smith and Lewis (2000, 2011) brought together these different traditions and conceptualized the theory of paradox in a more comprehensive way. This concept of paradox—defining as “contradictory yet interrelated elements that exist simultaneously and persist over time” (Smith & Lewis, 2011, p. 382)—is bounded by three core characteristics:

-

Opposition paradoxes involve organizational elements that “seem logical in isolation, but absurd and irrational when appearing simultaneously” (Lewis, 2000).

-

Interdependence these opposing elements must be inextricably related; they must be “two sides of the same coin” (Lewis, 2000).

-

Persistence these tensions cannot be definitively resolved because they “persist over time” (Smith & Lewis, 2011, p. 382).

The concept of paradox has been used by scholars to investigate multiple issues, as paradox theory is a theoretical lens that can offer useful insights into a variety of organizational phenomena (Lewis & Smith, 2014), such as change (Lüscher & Lewis, 2008), coopetition (Raza-Ullah, 2020), hybridity (Smith & Besharov, 2019), identity (Sheep et al., 2017), innovation and ambidexterity (Andriopoulos & Lewis, 2009), and leadership (Lewis et al., 2014; Smith et al., 2010). Recently, it has also been adopted to investigate sustainability issues because of its ability to offer better insights into the complexity of corporate sustainability (Hahn et al., 2014, 2015, 2018).

The Multidimensional Nature of Corporate Sustainability

Corporate sustainability regards the implementation of the sustainable development concept, which states that economic development in the present should not compromise the possibility of future generations to satisfy their needs (WCED, 1987). The concept of corporate sustainability has evolved over time, generating different definitions that are still debated (Bansal & Song, 2017; Montiel, 2008; Montiel & Delgado-Ceballos, 2014). The evolution the concept has first emphasized the environmental dimensions, identifying corporate sustainability as ecological sustainability (Shrivastava, 1995; Starik & Rands, 1995), then the development of the concept has led to highlight the threefold nature of this construct, defining corporate sustainability in terms of environmental, social, and economic dimensions (Bansal & Song, 2017; Gladwin et al., 1995). Nowadays, the concept has largely assumed this more comprehensive meaning, where the three dimensions of sustainability are interconnected.

In this work, we have adopted this approach, which had its first operationalization in the triple bottom line (TBL) framework (Carter & Rogers, 2008; Elkington, 1998). In the TBL framework social, environmental, and economic dimensions need to be satisfied simultaneously; thus, to be sustainable, companies need to preserve natural and social capital while running their business activities, which guarantees their economic sustainability over a long period (Dyllick & Hockerts, 2002). According to this framework, corporate sustainability is identified as the intersection of three principles (i.e., environmental integrity, social equity, and economic prosperity), which are interdependent but intrinsically related. Indeed, each of these principles represents a necessary but not sufficient condition; if any of the principles is not supported, economic development will not be sustainable (Bansal, 2005).

When such a multidimensional perspective is adopted to define corporate sustainability, its inherent complexity of corporate sustainability emerges. In this work, we adopt Bansal’s (2005) perspective on corporate sustainability, which allows us to underline its multidimensional nature (i.e., where social, environmental, and economic elements are intrinsically related) (Haffar & Searcy, 2017; Hahn et al., 2010; Reinecke & Ansari, 2016). As economic, social, and environmental aspects involve desirable yet interdependent and conflicting demands and objectives, corporate sustainability issues entail multiple tensions, contradictions, and conflicts that might undermine companies’ sustainability efforts.

Operationalizations of Paradox in Corporate Sustainability Studies

Firms are always confronted with tensions in their activities, but corporate sustainability is particularly characterized by inherent tensions; economic, social, environmental, concerns “reside at different levels, require change processes or operate in conflicting temporal and spatial frames” (Hahn et al., 2015, p. 301), and provide companies with multiple objective functions that can collide and generate conflicts (Jensen, 2001). Examples of these conflicts are standardization and efficiency vs. advancing environmental and social practices (Joseph et al., 2020), product quality vs. use of recycled/recovered raw materials (Daddi et al., 2019).

As conceptualized by Hahn et al., (2014, 2018), two approaches can be adopted in front of corporate sustainability tensions: the business case or the paradox perspective. The business case approach, which is widely used, interprets the conflicts between socio-environmental elements and economic ones as trade-offs, so the economic pole of the contradiction is finally emphasized over the others. Social and environmental issues become investments to achieve economic benefits—the true objective function of companies (Barnett et al., 2021; Jensen, 2001); just issues that allow win–win solutions are considered (Van der Byl & Slawinski, 2015). On the contrary, paradox theory frames conflicts between economic and socio-environmental demands and goals as paradoxes and thus accepts the tensions by addressing and managing the opposing poles simultaneously instead than picking one (Gao & Bansal, 2013; Hahn et al., 2015). Framing sustainability tensions through a paradox lens enables scholars to consider the complexity of sustainability problems, the intrinsic value of social and environmental elements, and their systemic nature.

While there is a clear consensus on the theoretical definition of paradox—leveraging the general definitions provided by Smith and Lewis (2011) and its conceptualization in corporate sustainability (Hahn et al., 2010, 2014, 2015, 2018)—the application of the concept in corporate sustainability studies is characterized by heterogeneous uses and meanings, which undermine the great potential of this theoretical frame. For example, the notion of paradox has been applied to identify concepts as diverse as both tensions (e.g., Daddi et al., 2019) and the strategies to tackle them (e.g., van Hille et al., 2019, p. 6).

Let us consider the literature review by Van der Byl and Slawinski (2015) as a narrative example. There is inherent ambiguity in the use of the construct because the authors simultaneously introduced different meanings at different levels of analysis without clearly defining and separating them. The concept of paradox seems to be adoptable equally to study tensions—“the paradox lens offers much promise to sustainability researchers looking to understand the tensions firms face when trying to be more socially or environmentally responsible” (p. 71), actions—“this lens has been developed to explain how companies attend to contradictory demands simultaneously” (p. 71), and thinking—“this entails a shift in approach to paradoxical thinking, meaning that managers and organizations must be capable of pulling together disparate elements” (p. 65)—in sustainability. A conceptual distinction between the different meanings and the levels of analysis to which they refer is missing and this makes the use of concept blurred.

Because of this conceptual confusion between uses and meanings, paradox in the sustainability literature can be defined as a fuzzy concepts—“an entity, phenomenon or process which possesses two or more alternative meanings and thus cannot be reliably identified or applied by different readers or scholars” (Markusen, 2003). Such an ambiguity contaminates its applications in empirical studies too, as the same concept is used with different meanings at different units of analysis, leading scholars to believe that “they are addressing the same phenomena but may actually be targeting quite different ones” (Markusen, 2003).

The ambiguity in the use makes current findings difficult to compare across studies because of the heterogeneous meanings and levels being investigated, affecting the possibility for researchers to compare and systemize the emerging evidence and the usefulness of research findings for practitioners. Practical implications remain blurred; it is not clear whether, for example, it is important for companies and individual actors to detect paradoxical tensions in sustainability, whether organizations need to train managers in order to develop a paradoxical mindset for coping with sustainability challenges (Carollo & Guerci, 2018; Wei et al., 2019), or whether they need to implement paradoxical strategies in order to manage competing elements of sustainability (Joseph et al., 2020; Slawinski & Bansal, 2012).

Therefore, the research questions guiding the present work are as follows: How has the concept of paradox been used in empirical research on corporate sustainability? What can sustainability literature learn from the existing empirical research? Indeed, the classification and conceptualization of the existing uses of paradox is needed to support scholars in better understanding the meanings involved (e.g., Lüdeke-Freund et al., 2018).

Research Methods

To avoid ambiguities and misunderstandings about the uses and meanings of paradox in empirical sustainability research, this study conducts a systemic review of the empirical literature. In order to identify the relevant publications in a rigorous and reliable manner, we structured the analysis along the eight-steps process developed by Tranfield et al. (2003), Denyer and Tranfield (2009), and Williams et al. (2017), complemented by an additional step—a snowballing procedure—to further verify for the possible exclusion of potentially useful articles (Wohlin, 2014). Accordingly, the entire review process consisted of nine steps, a screening of the published literature based on selected keywords, and a content analysis.

Determine Relevance of the Review and the Research Question. The first step involved defining whether reviewing the empirical papers adopting paradox theory to study corporate sustainability was necessary. As stated in the introduction, reviewing the empirical literature can clarify the empirical uses and operationalizations of the construct and offer a more integrated picture of the use of paradox theory in sustainability studies. Searches in ISI and SCOPUS returned no reviews focusing specifically on this topic. Another initial, essential step for a systematic literature review is to define clear research questions that facilitate the analysis of the study. As motivated in the previous paragraphs, the questions mentioned above were defined: How has the concept of paradox been used in empirical research on corporate sustainability? What can sustainability literature learn from the existing empirical research?

Definition of Temporal Boundaries and the Search Area. The third stage outlined the research boundaries. Initially, a specific period was not delimited to ensure that all relevant papers were included. An examination of the initial set of collected papers revealed that only 15% of the articles had been published prior to 2007. This year is an important threshold because in their review Van der Byl and Slawinski (2015) identified the first article to adopt the construct of paradox in sustainability as being published in 2007 (Berger et al., 2007). The titles and abstracts of papers published prior to 2007 were analyzed to avoid omitting any potential paradox articles, but none proved relevant to this analysis. Thus, the period considered was from 2007 to September 2021, when the manuscript has been submitted. Given that the existing literature is recent and addresses various subfields no restrictions on journal articles were imposed; differently from existing reviews that focused only on management top journals (Van der Byl & Slawinski, 2015). All articles that were published or in press in peer-reviewed academic journals, as presented in the data sources used for the analysis, were considered. To ensure the quality of the selected documents, the present study opted to run the research in two well-established scientific databases (ISI Web of Science and SCOPUS), the editorial standards of which include timeliness (i.e., regular periodicity), peer review of original research content, internationality of authors and editors, openness of the editorial board, and availability of titles and abstracts in English (Chavarro et al., 2018).

Development of the Search String and Inclusion Criteria. The next step was to develop a string of keywords to capture articles that focused on corporate sustainability tensions and adopted the concept of paradox. We adopted keywords used in the review by Van der Byl and Slawinski’s (2015), with minor changes.Footnote 1 The search string was as follows: (environmental performance OR environmental management OR environmental policy OR environmental issues OR natural environment OR pollution OR corporate sustainability OR sustainable development OR corporate social responsibility OR sustainability management OR business sustainability OR corporate responsibility) AND (dilemma* OR paradox* OR tension* OR integrative). Then, the inclusion and exclusion criteria were also developed in this step to define the papers that would be accepted in the final review. The inclusion criteria were as follows:

-

(i)

Empirical papers because the purpose of the review was to study how the concept of paradox is empirically applied in the field of corporate sustainability.

-

(ii)

Papers that address sustainability issues and tensions.

-

(iii)

Papers that use the concept of paradox, as defined by Lewis (2000), Schad et al. (2016), and Smith and Lewis (2011).

Choice of the Database and Search Mode. The fifth step defined the databases in which the review would be conducted. As mentioned above, to ensure the reliability and quality of the research, this review relies on two scientific databases, ISI and SCOPUS, as they are among the most commonly used, recurrent, and reliable (see, e.g., Haffar & Searcy, 2017; Williams et al., 2017). The search using the keyword string described above was performed in both databases to improve the consistency of the review and to capture potential articles. The research focuses on titles, abstracts, and the contents of papers in ISI and on titles, abstracts, and keywords in SCOPUS. Only papers published in English and categorized in the subareas of management (in ISI) or business, management, and accounting (in SCOPUS) were considered. Finally, the lists of articles found in the two databases were merged, and duplicates were deleted.

Developing Article Database and Snowballing Procedure. The sixth step involved screening titles and abstracts according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria defined in step four. If the adoption of the paradox construct was not clear, the entire paper was analyzed to decide on its inclusion in the final set. Of the articles published between 2007 and 2021, 60% were empirical papers, 30% were theoretical, and 10% were literature reviews. For the purpose of the analysis, in the sample, the identified papers focused on corporate sustainability tensions and applied the concept of paradox. Only 41 papers were identified as empirical research adopting this construct (see Fig. 1). While the keywords captured many studies (because the terms “paradox,” “dilemma,” and “tensions” are common in the sustainability literature), only a small number of the identified studies adopted the paradox concept. Such papers either explicitly referenced paradox theory or were identified via an inductive analysis of the content using the definitions provided by Smith and Lewis (2011) and Hahn et al. (2018).

PRISMA flow diagram modified from Liberati et al. (2009)

A forward and backward snowballing procedure was carried out on the initial set of papers to further improve the reliability of the review (Wohlin, 2014). The snowballing procedure described by Wohlin (2014) has two main phases. The first one, backward snowballing, involves screening the references of each paper in an initial set according to previously defined criteria. The second, forward snowballing, involves screening papers that quote the articles in the set. The resulting papers make up a second set to which the snowballing process is again applied. The procedure ends when no new articles are captured by either forward or backward snowballing. The snowballing process was applied in three separate rounds, adopting the same inclusion and exclusion criteria defined above, and resulted in the addition of 12 articles to the review.Footnote 2 Therefore, 53 papers were included in the review (see Table 1). The PRISMA flow diagram (Liberati et al., 2009; Moher et al., 2009) describes the screening process that allows to identify those papers, and list the number of papers excluded in each step (see Fig. 1).

Descriptive and Thematic Analysis. The last two methodological stages concerned the analysis of the selected papers. Step eight is the bibliometric analysis of the sample. Afterward, in step nine, a qualitative content analysis was performed to capture “the meanings associated with messages rather than with the number of times message variables occur” (Frey et al., 2000, p. 237). For the content analysis, ATLAS.ti software (ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH, Berlin, Germany) was used to search for recurring patterns in the papers’ contents and, on the basis of those patterns, inductively defined structural categories. Codes concerning the uses and meanings of paradox emerged inductively from the texts.

A Map of Paradox Theory Adoption in Corporate Sustainability Research

What is Paradox and How is It Adopted in Corporate Sustainability

This study aims to shed light on how scholars have used the concept of paradox to investigate corporate sustainability tensions. To do this, we build on seminal contributions that address other fuzzy concepts, such as absorptive capacity and ambidexterity (Cao et al., 2009; Lane et al., 2006). These studies conducted detailed analyses examining the ambiguity of the proposed constructs to assess how they had been used and to unpack their inherent characteristics, and we mimicked their efforts by conducting our own detailed analysis. The contents of collected papers were analyzed by adopting a general inductive coding process in which a particular set of ideas was grouped in an upper-level conceptual category (Corbin & Strauss, 1998; Saldana, 2013). Through an inductive coding process, the concept’s uses emerged. This process highlighted recurring patterns of how scholars use the construct of paradox to study corporate sustainability and allowed us to group the into upper-level conceptual categories.

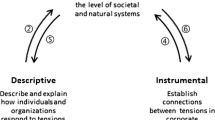

Based on the reading of the papers and the coding process, we reveal that the concept of paradox is used in three ways in corporate sustainability research: (1) detective use, (2) sensemaking use, and (3) responsive use.Footnote 3 However, the different ways in which scholars empirically use this construct influence its meaning. In other words, the use of a concept shapes its conceptual content. Indeed, in the selected works, the concept of paradox acquired three precise meanings as a consequence of its three uses: (1) paradoxical tensions, (2) paradoxical frame/thinking, and (3) paradoxical actions/strategies. Consequently, this identification of the three meanings allows us to categorize the existing heterogeneous literature into three distinct research streams with clear contents and well-defined conceptual boundaries and each grouped around a specific meaning. Figure 2 offers a graphical representation of our findings.

Detective Use of Paradox

The label detective use indicates when scholars adopt the construct of paradox as an analytical tool through which they investigate the nature of sustainability tensions; they detect which tensions can be considered paradoxes by utilizing the definition provided by Smith and Lewis (2011): paradoxes are “contradictory yet interrelated elements that exist simultaneously and persist over time” (p. 382). In other words, researchers use the concept of paradox as an external theoretical lens to examine the sustainability tensions present in the phenomenon under scrutiny (Morris et al., 1999), attempting to detect whether those tensions are paradoxical. An example that illustrates the detective use of paradox is found in González-González et al.’s (2019) study: “given the contradictory and dialectic nature of CSR, we use paradox in our study as a conceptual framework and analytical tool to enable us make sense of the consubstantial paradoxical tensions in CSR” (p. 3).

The detective use of the paradox constitutes a suitable approach to disentangling the complexity of corporate sustainability, making it clear which are the major challenges that cannot and should not be dismissed by individuals and organizations. Therefore, researchers should use paradox in a detective way (i.e., as an analytical tool) when they are interested in shedding light on the complexity of specific corporate sustainability domains. This approach can be useful in different management fields (e.g., strategy, organizational behavior, and business ethics) to identify, investigate, and highlight for business practitioners the nature of the paradoxical conflicts that individuals and organizations must deal with.

This specific use of paradox shapes its meaning. Indeed, when paradox is used in a detective way, it takes on the meaning of “paradoxical tensions” in the context of corporate sustainability. Paradoxical tensions thus constitute the first research stream that can be observed in existing studies, and 47% of the papers reviewed in our study were grouped in this category. In this research stream, scholars are focusing their efforts on detecting paradoxical tensions that characterize different sustainability domains, such as TBL (Ozanne et al., 2016), Bottom of the Pyramid projects (Brix-Asala et al., 2021), CSR (Discua Cruz, 2020; González-González et al., 2019), green human resources (HR) management (Guerci & Carollo, 2016), hybridity (Reynolds & Holt, 2021), supply chain (Brix-Asala et al., 2018; Schrage & Rasche, 2021; Zehendner et al., 2021), and circular economy (Daddi et al., 2019). Paradoxical tensions are investigated both at the individual level of analysis (i.e., the paradoxical tensions experienced by an organization’s members or involving individual dimensions) (Carollo & Guerci, 2018) and at the organizational level of analysis (i.e., tensions experienced at the organizational level or tensions among different organizations) (Longoni et al., 2019; Ozanne et al., 2016). Researchers are developing different ways to capture such paradoxical tensions, but only in a few cases do they empirically highlight the three constitutive aspects of paradox identified by Smith and Lewis (2011): interrelations, competition, and persistence. This finding points to the fact that measures of paradoxical tensions in sustainability are not yet well developed, as many studies generally refer to paradoxes without clearly distinguishing them from simple tensions. Therefore, while investigating sustainability tensions, researchers need to exercise more rigor in identifying the aspects of opposition, interrelation, and persistence within those tensions; this will enable them to correctly define the tensions as paradoxes.

Sensemaking Use of Paradox

In other articles, scholars consider paradox to be the cognitive frame or way of thinking adopted by business actors in making sense of sustainability-related tensions (i.e., accepting opposing corporate sustainability elements by framing these conflicts as paradoxes). By adopting a sensemaking use, scholars are able to study how individuals and organizations cognitively accept and integrate corporate sustainability tensions. For example, Busch et al. (2020) say, “we aimed to expand on existing theoretical developments, that is, sensemaking within paradox theory” (p. 2505). In the sensemaking use, the subject is not the researcher but the individual or the organization under investigation, who faces sustainability tensions and makes sense of them through paradoxical thinking or paradoxical frame. Sensemaking is “the process through which individuals work to understand novel, unexpected or confusing events” (Maitlis & Christianson, 2014, p. 57). Thus, in the context of this use, the construct of paradox assumes the meaning of “a paradoxical frame or way of thinking” (38% of the reviewed papers). Making sense of sustainability tensions in a paradoxical way (Child, 2019; Soderstrom & Heinze, 2019) means adopting a both/and mentality according to which opposing sustainability goals are not interpreted as trade-offs but are instead accepted as interrelated aspects that require simultaneous consideration, without dismissing any of the poles (Hahn et al., 2014). For example, Ashraf et al. (2019) say, “when organizations hold a complex (or paradoxical) frame of sustainability with many elements, they ‘accept tensions and accommodate conflicting yet interrelated economic, environmental, and social concerns, rather than eliminate them’” (p. 3).

Thus, paradoxical frame/thinking is the second research stream that can be observed in the existing literature. Publications in this stream aim at investigating the cognitive frame through which managers or organizations deal with contradictions embedded in sustainability, accept them, and become aware of the importance of maintaining these competing elements together. Paradoxical frame/thinking has been studied both at the individual level (i.e., how single managers make sense of tensions in corporate sustainability by considering competing elements simultaneously) and at the organizational level (i.e., how companies frame corporate sustainability tensions at the organizational level). Scholars in this research stream are investigating the processes that allow the development of a paradoxical frame/thinking (Carollo & Guerci, 2018; Sharma & Bansal, 2017; Smith & Besharov, 2019). However, the implementation of this frame/thinking can be affected by individual and organizational factors, such as time horizon, organizational culture, and agency conditions (Berger et al., 2007; Sharma & Jaiswal, 2018; Xiao et al., 2019). Moreover, findings in this research stream can benefit corporate practitioners, making them aware of potential ways to cognitively address sustainability tensions.

Responsive Use of Paradox

The label responsive use identifies cases where paradox is understood as the actions implemented by business actors to manage sustainability tensions (i.e., actions that integrate and purse competing social, environmental, and economic elements simultaneously). As for sensemaking use, the subject of this use is not the researcher but individuals and organizations under investigation and that manage sustainability tensions through paradoxical responses, and this use of paradox was identified in 32% of the articles we reviewed. By adopting the concept of paradox in a responsive way, it assumes the meaning of “paradoxical actions/strategies” through which individuals and organizations can manage proactively opposing sustainability elements by simultaneously integrating them and without emphasizing only one goal.

Therefore, in our review of the selected literature, paradoxical actions/strategies emerged as the third possible research stream. In this stream, scholars investigate the strategies and actions implemented by companies, managers, and employees to cope with sustainability tensions and integrate conflicting sustainability goals, pursuing them simultaneously. The analysis are conducted at both the individual level (i.e., how the single managers or employees respond to sustainability-related tensions) (Hengst et al., 2020) and organizational level (i.e., organizational paradoxical strategies implemented to address corporate sustainability tensions) (Ashraf et al., 2019; Siegner et al., 2018; Slawinski & Bansal, 2012). Few studies embrace an interorganizational perspective (Schrage & Rasche, 2021).

Inside this research stream, scholars are mainly studying the processes implemented to cope with sustainability tensions (e.g., both/and responses, integrative strategies, separation in time and space, juxtaposition, synthesis, ambitemporality, and ambidexterity), highlighting crucial contingent factors that influence paradoxical responses implementation and outcomes: (i) time (e.g., long time horizon, patient approach); (ii) space (e.g., creating a space for negotiations) (Battilana et al., 2015) and separation in different areas of roles, duties, goals, and demands; (iii) collaboration; and (iv) proactivity. Moreover, in these studies there is a belief that paradoxical responses can support better social, environmental, and economic results (Ashraf et al., 2019; Peng et al., 2016); for example, through the regeneration of place (Slawinski et al., 2019) and development of sustainable business models (Stubbs, 2019; van Bommel, 2018). However, knowledge on the outcomes of paradoxical actions/strategies is still underdeveloped.

The responsive use constitutes an effective approach (especially for strategy scholars) to investigating and detecting the various practical responses adopted by individual and organizations to cope with tensions in corporate sustainability in a both/and way. Therefore, researchers should approach paradox in a responsive way when they intend to understand how companies or organizational members can actively manage conflicting goals simultaneously and which outcomes might be generated by such actions. This research stream can generate useful knowledge for practitioners by showing what are the processes to integrate conflicting sustainability goals, what resources are needed for implementing these strategies, and what outcomes can be achieved.

A Systems Perspective on the Use of Paradox Theory in Corporate Sustainability Research

The research streams we have identified are conceptually distinct but not isolated from each other. Indeed, paradoxical tensions, paradoxical frame/thinking, and paradoxical actions/strategies can be investigated in terms of their interconnections and across different levels of analysis. Nevertheless, the selected studies use the concept of paradox mainly with a linear perspective (i.e., with one meaning and at one level of analysis—either organizational or individual) to investigate corporate sustainability issues. For example, there are (1) studies that investigate paradoxical tensions at the organizational or interorganizational level (e.g., by “adopt[ing] a paradox theory to explore the paradoxical tensions that arise in the HRM area when companies decide to pursue environmental sustainability goals”; Guerci & Carollo, 2016, p. 213), (2) research that explores contributions related to paradoxical frame/thinking at the individual or organizational level (e.g., by “build[ing] on the argument that paradoxical frames are critical for understanding the success of sustainability initiatives”; Sharma & Jaiswal, 2018, p. 292), and (3) research that examines paradoxical actions (e.g., by studying organizations that “actively [trigger] place-based tensions, and then [manage] them paradoxically”; Slawinski et al., 2019).

However, the three meanings of paradox lead to three research streams that are distinct, with a clear and defined object of analysis, but that are not mutually exclusive. For this reason, it is crucial to connect such streams and investigate how they can influence each other. Furthermore, most of the literature considers just one level of analysis at a time, ignoring the relationships between individuals and the organizations they belong to and between the organizations and the more general systems of which they are part. Failure to examine the possible interconnections across paradoxical tensions, paradoxical frame/thinking, and paradoxical actions/strategies leads to an over-simplification, limiting their understanding. We claim that a system perspective is needed—one that “focuses on the interconnections among elements in a system, arguing that a phenomenon cannot be explained only by analyzing its parts—one must understand the relationships among the parts” (Bansal & Song, 2017). Indeed, integration across paradoxical tensions, paradoxical frame/thinking, and paradoxical actions/strategies (as well as, perhaps, their levels of analysis) allows a better understanding of the complexity of corporate sustainability; this is achieved by holistically considering the nature of corporate sustainability tensions, along with the various approaches and responses to such tensions (Schad & Bansal, 2018; Williams et al., 2017).

Along this line, in the following paragraphs, we organize our findings into a theoretical framework that can synthetize existing evidence on paradoxical tensions, paradoxical frame/thinking, and paradoxical actions/strategies in sustainability; this is achieved while considering the different levels of analysis and their interconnections and highlighting research gaps, thus paving the way for a more system-oriented development of paradox theory that “extend[s] the literature’s current scope to paradoxes rooted in complex systems” (Schad & Bansal, 2018).

The conceptual framework we propose (depicted in Fig. 3) offers a holistic interpretation of the adoption of paradox theory in corporate sustainability research by integrating detected paradoxical meanings and their possible levels of analysis in a horizontal way (i.e., across the meanings that the concept of paradox has assumed so far in sustainability studies) and in a vertical way (i.e., across the different levels of analysis: individual, organizational, and system).

Considering the framework according to a horizontal perspective clarifies the interconnections between paradoxical tensions, frame/thinking, and actions/strategies. Indeed, the presence of paradoxical tensions in corporate sustainability (at the individual, organizational, and system levels) opens up the possibility for individuals or organizations to develop paradoxical sensemaking and to implement paradoxical responses to manage them. This has already been demonstrated within the current literature; for example, Reinecke and Ansari (2015) show that contradictory time orientations lead organizations to engage in “temporal brokerage” to negotiate diverse temporalities. Even paradoxical frame/thinking and paradoxical actions/strategies can be connected on a theoretical level because they affect each other. Indeed, thinking paradoxically at the individual level or developing an organizational paradoxical frame can lead to the implementation of paradoxical actions or vice versa. For example, Sharma and Bansal (2017) showed that actors who perceived paradoxical elements in an imperative (reality) or in a fluid way (socially constructed) aligned their actions accordingly.

Taking into consideration the vertical perspective, we highlight how each distinct meaning of paradox in sustainability needs to be conceptualized and investigated across its different levels of analysis. While no study so far has adopted a systems level as the unit of analysis, we propose to include it in our framework, as sustainability issues pose systems-based problems that must be addressed according to a broader view to be solved (Bansal & Song, 2017; Holling, 2001; Schad & Bansal, 2018; Williams et al., 2017). In the existing studies, paradoxical tensions mainly concern the individual level, which includes managers, leaders, CSR managers, and organization employees (e.g., Carollo & Guerci, 2018), or the organizational level, which includes companies, NGOs, and social enterprises (e.g., Daddi et al., 2019). These two existing levels of analysis for corporate sustainability tensions are not separate entities, as they can influence each other and produce new types of conflicts (Hahn et al., 2015). Regarding paradoxical frame/thinking, two levels of analysis can be adopted: (1) the individual one, which involves the paradoxical thinking of individual actors to make sense of sustainability conflicts (e.g., Sharma & Jaiswal, 2018; Soderstrom & Heinze, 2019), and (2) the organizational one, which involves the use of the organizations’ frame to make sense of sustainability tensions (e.g., Ashraf et al., 2019). Researchers of paradoxical frame/thinking in sustainability are currently investigating the two levels separately, and an analysis of how individual paradoxical thinking (especially from managers and CEOs) can influence the sensemaking of the entire organization or vice versa is currently missing. Future research is needed to understand how paradoxical frame/thinking is conveyed within organizations. Finally, even paradoxical actions/strategies to manage sustainability tensions can be implemented at the individual level (e.g., Ahmadsimab & Chowdhury, 2019), organizational level (e.g., Slawinski et al., 2019; van Hille et al., 2019), and systems level. Currently, the majority of the relevant research concerns the organizational level, a minority concerns the individual level, and no research has been conducted on the systems level.

A future research agenda

The effort of reading our review’s findings through a systems lens contributes to the development of the paradox and sustainability field by providing a framework that indicates how to connect paradoxical tensions, frame/thinking, and actions/strategies in corporate sustainability research and across the various levels of analysis. Adding a systems perspective to such literature is crucial to (1) fostering the literature’s potential to offer results relevant to corporate sustainability practice, (2) being able to offer insights regarding systemic sustainability challenges, their nature, and their implications, and (3) positively approach and proactively address the complexity of sustainability challenges. We believe that this framework will allow scholars to better position their research to investigate the relationships between other paradox research streams in sustainability, and that it provides the primary guidelines to support the strong development of such an approach.

Our mapping of the existing research shows that scholars are mainly focused on detecting paradoxical tensions in corporate sustainability. However, we believe that the crucial contribution of this approach relies on the other two streams (i.e., paradoxical frame/thinking and paradoxical actions/strategy), as they constitute the cognitive and practical alternatives to the classical business case perspective. Thus, scholars should extend such research streams by adopting paradox mainly in sensemaking and responsive way and investigating the individual and organizational factors that make it possible to develop paradoxical thinking and strategies to address corporate sustainability tensions as well as the outcomes of these frame and actions.

The existing studies around paradoxical frame/thinking mainly reflect on the managerial cognitive frame and the managers’ abilities to consider sustainability in a more holistic way. Research is missing concerning how such a mindset can be integrated at different organizational levels and become the frame of the entire organization. Instead, the current research related to paradoxical strategies in corporate sustainability is still underdeveloped, and there are two main areas of study that require further exploration to foster the potential of this approach: (1) the contingent factors that make such paradoxical strategies possible (e.g., power conditions, resources), and (2) the outcomes—both negative and positive—in the environmental, social, and economic dimensions of these both/and responses. However, just a few of the existing studies focus on the outcomes that such strategies produce, and those outcomes are a key aspect to understanding the real impact of this approach.

Moreover, the link between these two streams of paradox research in corporate sustainability field is still under-researched, and further research is needed as the connections between paradoxical frame/thinking and paradoxical actions/strategies are a key aspect to understand in order to develop the potential of a paradox approach in corporate sustainability. Research is needed on whether paradoxical frame/thinking and actions/strategies are consequential or autonomous, how they influence each other across levels, and what their impact is on sustainability goals at the system level. For example, sustainability managers or people working in hybrid organizations or social organizations may not frame tensions as paradoxical, but their strategies and actions can be labeled as paradoxical (e.g., juxtaposition, integration, ambitemporality). Similarly, having a paradoxical frame/thinking may not be enough to turn this approach into paradoxical actions because, in addressing sustainability challenges, a both/and perspective is not always possible due to time horizons, resource scarcity, and power conditions (Berti & Simpson, 2021; Slawinski & Bansal, 2015).

Additionally, environmental and social challenges (e.g., biodiversity loss, climate change and greenhouse gas emissions, and modern slavery) involve many social, environmental, and economic elements at different levels of analysis that are simultaneously interrelated yet conflicting. Therefore, a broader view is needed in studying the nature of sustainability tensions; this is necessary to develop the potential of the literature to address corporate sustainability challenges, as current studies see tensions mainly from an individual or organizational perspective, which does not allow us to take into account all the aspects and actors involved (Schad & Bansal, 2018). Scholars should focus more on the analysis of paradoxical tensions at the systems level by deepening their understanding of how they translate into organizational and individual ones and by considering their impacts beyond the organizational boundaries, that is on social and natural systems. Moreover, research on system-level responses to tensions that have a systemic nature, such as sustainability conflicts, is not yet available. However, systems level research on paradoxical actions/strategies constitutes another crucial level of analysis because socio-environmental challenges pose complex and systems-based problems in which multiple elements are interrelated; thus, they require systemic actions and strategies to be effectively addressed. Scholars investigating such paradoxical tensions and actions/strategies at the system level can “further extend paradox theory in their quest to provide solutions for the world’s most pressing problems” (Schad & Bansal, 2018, p. 1503). Therefore, we believe this systems lens needs to be adopted in future research.

Using Paradox to Reconnect Society and Business Ethics?

So far, the connection between paradox theory and business ethics has not been adequately studied. Yet, paradox perspectives on sustainability open up important space to understand ethical decision-making, especially as far as a systems perspective is adopted. In the following paragraphs, we discuss how the framework developed in this article regarding the various meanings of paradox can help business ethics scholars to better understand, evaluate, and guide the actions of business actors in addressing the most pressing social and environmental challenges of our time (Islam & Greenwood, 2021). We also highlight fruitful avenues for future research at the crossroads of business ethics and paradox research.

First, the very existence of paradoxical tensions is a key element to inform business ethics scholars’ research efforts. Conflicts are an unavoidable experience for those who deal seriously with sustainability, and, therefore, it is necessary to know how to act in the face of conflict—how to behave in front of elements that are in opposition to each other but that are all of value. Thus, reflection on ethical decision-making is required. Sustainability tensions occur across different levels, generating contrast between socio-environmental aspects regarding individuals, organizations, and systems. As these levels are distinct yet interrelated, ethical questions arise when social and environmental elements at different levels of analysis are found to be in opposition; for example, one can consider the ethical implications of the tensions between businesses in the oil and gas sector and climate change consequences (Ferns et al., 2019). Indeed, “factors rendering tensions salient include environmental [social] and ethical issues such as change and scarcity. Also, individual [and organizational] actors are expected to perceive tensions based on the priorities and values they hold. Once a tension is salient, the individual chooses to manage it or dismiss it” (Joseph et al., 2020, p. 351). Therefore, the use of paradox as “paradoxical tensions” offers business ethics scholars a specific field of research that they can explore to contribute to the understanding of the nature and management of paradoxical tensions. Indeed, the business ethics reflection, by offering criteria for assessing the relevance of opposing poles involved at different levels, can provide important insights regarding the salience of such conflicts and whether to integrate opposing yet interrelated elements.

Second, business ethics literature has increasingly highlighted the importance of challenging the established instrumental understandings of sustainability (Hahn et al., 2018; Johnsen, 2021) to overcome the so-called business case approach. In a recent paper, Johnsen (2021) underlined that “business case deprives the sustainability concept of its political and ethical dimensions” (p. 3) because it considers sustainability in an instrumental way and without intrinsic value. By adopting a business case perspective in the management of social and environmental conflicts, the ethical question is dismissed, as choices become about only what kind of investments should be made in sustainability to achieve economic gains. Furthermore, by considering social and environmental concerns only as investments to improve economic performance (thus eliminating their ethical and value components), the ability of companies’ sustainability programs to lead to changes that can benefit society is weakened (Barnett et al., 2021; Ergene et al., 2020). On the contrary, we propose paradox theory as a promising alternative to inform the ethical decision-making of business actors in the face of sustainability tensions. In particular, we claim that paradoxical frame/thinking and paradoxical actions/strategies can overcome the business case’s limitations, allowing “an immanent evaluation of the value of sustainability [conflicts]” (Johnsen, 2021, p. 2)—one where there is not a priori knowledge on what forms of sustainability are possible and therefore opens up space for creative solutions that question and go beyond the principles of an instrumental approach. Indeed, paradoxical frame/thinking and actions/strategies allow to address the complexity of sustainability by trying to imagine and build new ways to respond to its conflicts to achieve opposite goals simultaneously. Paradoxical frame/thinking and actions/strategies can provide business ethics scholars with organizational practices to overcome the classical business case approach, which deprives sustainability of its complexity without offering the possibility of significantly contributing to sustainable development (Ergene et al., 2020).

Conclusion

Tensions and conflicts in corporate sustainability are a daily experience for companies; they cannot avoid them if they want to be truly sustainable. That is not for them to decide, all they have to decide is what to do to address them, prioritizing economic over sustainability benefits or navigating such complexity aiming at achieving both. The concept of paradox is increasingly used to study such challenges. Yet, its empirical application suffers from an inherent ambiguity, and its fuzzy nature might hinder its ability to serve as a promising alternative to the mainstream business case approach. Using content analysis and a systematic literature review, we outline the heterogeneous uses and meanings the concept of paradox has assumed in empirical research so far, systematizing the existing fuzzy literature in three clear and distinct (but not isolated) research streams. Indeed, we suggest that paradox has been used to identify: (i) a specific category of tensions, (ii) how actors make sense of those tensions, and (iii) the specific actions or strategies they enact to respond to those tensions. Furthermore, we systematize the emerging evidence for the consideration of different levels of analysis (i.e., individual, organizational, and systems) in the development of a system-oriented framework, which highlights avenues for future research at the intersection of paradox theory, corporate sustainability and business ethics.

We contribute to the literature on paradox in sustainability in two ways. First, by clearly defining the different empirical uses of the concept and its meanings, offering a useful companion to researchers to take stock of existing evidence and navigate across the three existing research streams. Confusing uses and meanings of the concept of paradox would fail to offer evidence relevant to corporate and managerial practice. Second, by proposing a novel way to extend it and incorporate a systems perspective, overcoming the linear view adopted in most current studies, which has focused solely on the individual or organizational levels of analysis (Schad & Bansal, 2018; Williams et al., 2017). This simultaneous distinction and integration of meanings of paradox and level of analysis can extend the capacity of paradox theory to study sustainability issues in their complexity and enable the development of a literature able to impact effectively on policy-makers' and managers' decision making.

While our research focused on the corporate sustainability domain, we believe our map and framework can be useful instruments in advancing paradox research in general organization studies, supporting the identification of empirical evidence that can be relevant both for research and management practice. The concept of paradox is at risk of being too vague and indeterminate, and, therefore, irrelevant for corporate and managerial practice, producing confusing and non-comparable findings. Our framework can help scholars to be more precise in their studies by offering them a refined definition of paradox, with clear contents and well-defined boundaries, while also providing them with suggestions for future research in which they can integrate different levels of analysis. Finally, we contribute to the business ethics literature by suggesting how the three meanings of paradox identified might offer a viable alternative to the instrumental view of sustainability, enabling a more nuanced theory-building of ethical decision-making. In particular, paradox frame/thinking and actions/strategies can constitute a more “immanent” way of approaching the complexity of corporate sustainability (i.e., where a clear path for action is not given).

Like all academic studies, we acknowledge that there are limitations to our study. First, although we adopted a rigorous methodology for the identification of the papers to be reviewed, we cannot exclude the possibility that our string search led to the omission of some papers (i.e., in cases where the concept of paradox was not explicitly mentioned). However, we are confident that the systematic review procedure we adopted has ensured breadth and rigor in our article selection. Second, while we adopted a systematic application of inductive codes to the whole text of the selected papers to mitigate possible interpretation biases, we acknowledge that the coding process entails a degree of subjectivity regarding the uses and meanings detected.

In conclusion, our review of the emerging literature on paradox theory and sustainability aims at fostering the potential of the paradox concept “to unshackle the research on corporate sustainability from the hegemony of the business case” (Hahn et al., 2018, p. 245). We aim to achieve this by tackling the fuzziness of this promising construct and suggesting how to investigate it through the adoption of a systems standpoint. In the coming years, we will face many daunting societal challenges, and we hope that this review will support the application of paradox theory in the study of corporate sustainability, including a business ethics perspective.

Change history

18 July 2022

The original online version of this article was revised: Missing Open Access funding information has been added in the Funding Note.

Notes

Some of the words considered by Van der Byl and Slawinski (win–win, business case, trade-off) were excluded to delimit the research to the concept of paradox; their contribution had a broader focus on sustainability tensions management.

A common feature of the articles collected via snowballing is a focus on the social aspects of sustainability, which were not fully captured in the string developed by Van der Byl and Slawinski (2015) or in studies in which the use of paradox theory was not clear and explicit.

In a few cases, two of the highlighted uses were present. Four adopted a detective use first but were followed by a responsive one. Four applied a detective use followed by a sensemaking one. One combined a sensemaking use and a responsive use.

References

Ahmadsimab, A., & Chowdhury, I. (2019). Managing tensions and divergent institutional logics in firm–NPO partnerships. Journal of Business Ethics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-019-04265-x

Andriopoulos, C., & Lewis, M. W. (2009). Exploitation–exploration tensions and organizational ambidexterity: Managing paradoxes of innovation. Organization Science, 20(4), 696–717.

Ashraf, N., Pinkse, J., Ahmadsimab, A., Ul-Haq, S., & Badar, K. (2019). Divide and rule: The effects of diversity and network structure on a firm’s sustainability performance. Long Range Planning, 52(6), 101880. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2019.04.002

Bansal, P. (2005). Evolving sustainably: A longitudinal study of corporate sustainable development. Strategic Management Journal, 26(3), 197–218. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.441

Bansal, P., Grewatsch, S., & Sharma, G. (2020). How COVID-19 informs business sustainability research: It’s time for a systems perspective. Journal of Management Studies. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12669

Bansal, P., & Song, H. C. (2017). Similar but not the same: Differentiating corporate sustainability from corporate responsibility. Academy of Management Annals, 11(1), 105–149. https://doi.org/10.5465/annals.2015.0095

Barnett, M. L., Cashore, B. W., Henriques, I., Husted, B. W., Rajat, P., & Pinske, J. (2021). Reorient the business case for corporate sustainability. Stanford Social Innovation Review. https://doi.org/10.48558/fn21-my74

Battilana, J., Sengul, M., Pache, A. C., & Model, J. (2015). Harnessing productive tensions in hybrid organizations: The case of work integration social enterprises. Academy of Management Journal, 58(6), 1658–1685. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2013.0903

Benson, J. K. (1977). Organizations: A dialectical view. Administrative Science Quarterly, 22(1), 1–21.

Berger, I. E., Cunningham, P. H., & Drumwright, M. E. (2007). Mainstreaming corporate social responsibility: Developing markets for virtue. California Management Review, 49(4), 132–157. https://doi.org/10.2307/41166409

Berti, M., & Simpson, A. V. (2021). The dark side of organizational paradoxes: The dynamics of disempowerment. Academy of Management Review, 46(2), 252–274. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2017.0208

Brix-Asala, C., Geisbüsch, A. K., Sauer, P. C., Schöpflin, P., & Zehendner, A. (2018). Sustainability tensions in supply chains: A case study of paradoxes and their management. Sustainability (Switzerland), 10(2), 424. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10020424

Brix-Asala, C., Seuring, S., Sauer, P. C., Zehendner, A., & Schilling, L. (2021). Resolving the base of the pyramid inclusion paradox through supplier development. Business Strategy and the Environment, April, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2798

Busch, T., Richert, M., Johnson, M., & Lundie, S. (2020). Climate inaction and managerial sensemaking: The case of renewable energy. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 27(6), 2502–2514. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1972

Calabretta, G., Gemser, G., & Wijnberg, N. M. (2017). The interplay between intuition and rationality in strategic decision making: A paradox perspective. Organization Studies, 38(3–4), 365–401.

Cao, Q., Gedajlovic, E., & Zhang, H. (2009). Unpacking organizational ambidexterity: Dimensions, contingencies, and synergistic effects. Organization Science, 20(4), 781–796. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1090.0426

Carmine, S., & Smith, W. K. (2021). Organizational paradox. Oxford Bibliographies in Management. https://doi.org/10.1093/OBO/9780199846740-0201

Carollo, L., & Guerci, M. (2018). ‘Activists in a Suit’: Paradoxes and metaphors in sustainability managers’ identity work. Journal of Business Ethics, 148(2), 269. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3582-7

Carter, C. R., & Rogers, D. S. (2008). A framework of sustainable supply chain management: Moving toward new theory. International Journal of Physical Distribution and Logistics Management, 38(5), 360–387. https://doi.org/10.1108/09600030810882816

Chavarro, Di., Ràfols, I., & Tang, P. (2018). To what extent is inclusion in the Web of Science an indicator of journal “quality”? Research Evaluation, 27(2), 106–118. https://doi.org/10.1093/reseval/rvy001

Child, C. (2019). Whence paradox? Framing away the potential challenges of doing well by doing good in social enterprise organizations. Organization Studies. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840619857467

Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (1998). Basics of qualitative research techniques. Sage Publications.

Daddi, T., Ceglia, D., Bianchi, G., & de Barcellos, M. D. (2019). Paradoxical tensions and corporate sustainability: A focus on circular economy business cases. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 26(4), 770–780. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1719

Denyer, D., & Tranfield, D. (2009). Producing a systematic review. In The SAGE handbook of organizational research methods (pp. 671–689). Sage Publications Ltd. http://psycnet.apa.org/record/2010-00924-039

Discua Cruz, A. (2020). There is no need to shout to be heard! The paradoxical nature of corporate social responsibility (CSR) reporting in a Latin American family small and medium-sized enterprise (SME). International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship, 38(3), 243–267. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242619884852

Dyllick, T., & Hockerts, K. (2002). Beyond the business case for corporate sustainability. Business Strategy and the Environment, 11(2), 130–141.

Elkington, J. (1998). Cannibals with forks: The triple bottom line of 21st century business. New Society Publishers.

Ergene, S., Banerjee, S. B., & Hoffman, A. J. (2020). (Un)sustainability and organization studies: Towards a radical engagement. Organization Studies. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840620937892

Ferns, G., Amaeshi, K., & Lambert, A. (2019). Drilling their own graves: How the European oil and gas supermajors avoid sustainability tensions through mythmaking. Journal of Business Ethics, 158(1), 201–231. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3733-x

Ferraro, F., Etzion, D., & Gehman, J. (2015). Tackling grand challenges pragmatically: Robust action revisited. Organization Studies, 36(3), 363–390. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840614563742

Figge, F., & Hahn, T. (2020). Business- and environment-related drivers of firms’ return on natural resources: A configurational approach. Long Range Planning, April, 102066. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2020.102066

Frey, L., Botan, C., & Kreps, G. (2000). Investigating communication. Allyn & Bacon.

Gao, J., & Bansal, P. (2013). Instrumental and integrative logics in business sustainability. Journal of Business Ethics, 112(2), 241–255.

Gladwin, T. N., Kennelly, J. J., & Krause, T.-S. (1995). Shifting paradigms for sustainable development: Implications for management theory and research. Academy of Management Review, 20(4), 874–907. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1995.9512280024

González-González, J. M., Bretones, F. D., González-Martínez, R., & Francés-Gómez, P. (2019). “The future of an illusion”: A paradoxes of CSR. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 32(1), 2–14. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOCM-01-2018-0018

Grewatsch, S., Kennedy, S., & Bansal, P. (2021). Tackling wicked problems in strategic management with systems thinking. Strategic Organization. https://doi.org/10.1177/14761270211038635

Guerci, M., & Carollo, L. (2016). A paradox view on green human resource management: Insights from the Italian context. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 27(2), 212–238. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2015.1033641

Haffar, M., & Searcy, C. (2017). Classification of trade-offs encountered in the practice of corporate sustainability. Journal of Business Ethics, 140(3), 495–522. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2678-1

Hahn, T., Figge, F., Pinkse, J., & Preuss, L. (2010). Editorial trade-offs in corporate sustainability: You can’t have your cake and eat it. Business Strategy and the Environment, 19(4), 217–229. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.674

Hahn, T., Figge, F., Pinkse, J., & Preuss, L. (2018). A paradox perspective on corporate sustainability: Descriptive, instrumental, and normative aspects. Journal of Business Ethics, 148(2), 235–248. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3587-2

Hahn, T., Pinkse, J., Preuss, L., & Figge, F. (2015). Tensions in corporate sustainability: Towards an integrative framework. Journal of Business Ethics, 127(2), 297–316. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2047-5

Hahn, T., Preuss, L., Pinkse, J., & Figge, F. (2014). Cognitive frames in corporate sustainability: Managerial sensemaking with paradoxical and business case frames. Academy of Management Review, 39(4), 463–487. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2012.0341

Hargrave, T. J., & Van de Ven, A. H. (2017). Integrating dialectical and paradox perspectives on managing contradictions in organizations. Organization Studies, 38(3–4), 319–339. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840616640843

Hengst, I. A., Jarzabkowski, P., Hoegl, M., & Muethel, M. (2020). Toward a process theory of making sustainability strategies legitimate in action. Academy of Management Journal, 63(1), 246–271. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2016.0960

Holling, C. S. (2001). Understanding the complexity of economic, ecological, and social systems. Ecosystems, 4(5), 390–405. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-001-0101-5

Islam, G., & Greenwood, M. (2021). Reconnecting to the social in business ethics. Journal of Business Ethics, 170(1), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-021-04775-7

Jensen, M. C. (2001). Value maximization, stakeholder theory, and the corporate objective function. Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, 14(3), 8–21.

Johnsen, C. G. (2021). Sustainability beyond instrumentality: Towards an immanent ethics of organizational environmentalism. Journal of Business Ethics, 172(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-019-04411-5

Joseph, J., Borland, H., Orlitzky, M., & Lindgreen, A. (2020). Seeing versus doing: How businesses manage tensions in pursuit of sustainability. Journal of Business Ethics, 164(2), 349–370. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-018-4065-1

Lane, P. J., Koka, B. R., & Pathak, S. (2006). The reification of absorptive capacity: A critical review and rejuvenation of the construct. Academy of Management Review, 31(4), 833–863. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.2006.22527456

Lewis, M. W. (2000). Exploring paradox: Toward a more comprehensive guide. Academy of Management Review, 25(4), 760–776. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.2000.3707712

Lewis, M. W., Andriopoulos, C., & Smith, W. K. (2014). Paradoxical leadership to enable strategic agility. California Management Review, 56(3), 58–77. https://doi.org/10.1525/cmr.2014.56.3.58

Lewis, M. W., & Smith, W. K. (2014). Paradox as a metatheoretical perspective: Sharpening the focus and widening the scope. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 50(2), 127–149. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021886314522322

Liberati, A., Altman, D. G., Tetzlaff, J., Mulrow, C., Gøtzsche, P. C., Ioannidis, J. P. A., Clarke, M., Devereaux, P. J., Kleijnen, J., & Moher, D. (2009). The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 62(10), e1–e34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.006

Liu, Y., Mai, F., & MacDonald, C. (2019). A big-data approach to understanding the thematic landscape of the field of business ethics, 1982–2016. Journal of Business Ethics, 160(1), 127–150. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-018-3806-5

Longoni, A., Luzzini, D., Pullman, M., & Habiague, M. (2019). Business for society is society’s business: Tension management in a migrant integration supply chain. Journal of Supply Chain Management, 55(4), 3–33. https://doi.org/10.1111/jscm.12213

Lüdeke-Freund, F., Carroux, S., Joyce, A., Massa, L., & Breuer, H. (2018). The sustainable business model pattern taxonomy—45 Patterns to support sustainability-oriented business model innovation. Sustainable Production and Consumption, 15, 145–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spc.2018.06.004

Lüscher, L. S., & Lewis, M. W. (2008). Organizational change and managerial sensemaking: Working through paradox. Academy of Management Journal, 51(2), 221–240. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMJ.2008.31767217

Maitlis, S., & Christianson, M. (2014). Sensemaking in organizations: Taking stock and moving forward. Academy of Management Annals, 8(1), 57–125. https://doi.org/10.1080/19416520.2014.873177

Markusen, A. (2003). Fuzzy concepts, scanty evidence, policy distance: The case for rigour and policy relevance in critical regional studies politiques pertinentes dans les études régionales critiques. Regional Studies, 37(6–7), 701–717. https://doi.org/10.1080/0034340032000108796

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 62(10), 1006–1012. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005

Montiel, I. (2008). Corporate social responsibility and corporate sustainability: Separate pasts, common futures. Organization and Environment, 21(3), 245–269. https://doi.org/10.1177/1086026608321329

Montiel, I., & Delgado-Ceballos, J. (2014). Defining and measuring corporate sustainability: Are we there yet? Organization and Environment, 27(2), 113–139. https://doi.org/10.1177/1086026614526413

Morris, M. W., Leung, K., Ames, D., & Lickel, B. (1999). Views from inside and outside: Integrating emic and etic insights about culture and justice judgment. Academy of Management Review, 24(4), 781–796. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.1999.2553253

Ozanne, L. K., Phipps, M., Weaver, T., Carrington, M., Luchs, M., Catlin, J., Gupta, S., Santos, N., Scott, K., & Williams, J. (2016). Managing the tensions at the intersection of the triple bottom line: A paradox theory approach to sustainability management. Journal of Public Policy and Marketing, 35(2), 249–261. https://doi.org/10.1509/jppm.15.143

Pecl, G. T., Araújo, M. B., Bell, J. D., Blanchard, J., Bonebrake, T. C., Chen, I. C., Clark, T. D., Colwell, R. K., Danielsen, F., Evengård, B., Falconi, L., Ferrier, S., Frusher, S., Garcia, R. A., Griffis, R. B., Hobday, A. J., Janion-Scheepers, C., Jarzyna, M. A., Jennings, S.,…,Williams, S. E. (2017). Biodiversity redistribution under climate change: Impacts on ecosystems and human well-being. Science, 355(6332). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aai9214

Peng, M. W., Li, Y., & Tian, L. (2016). Tian-ren-he-yi strategy: An Eastern perspective. Asia–Pacific Journal of Management, 33(3), 695–722. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-015-9448-6

Putnam, L. (1986). Contradictions and paradoxes in organizations. Organization Communication: Emerging Perspective, 1(151–167), 151–167.

Raza-Ullah, T. (2020). Experiencing the paradox of coopetition: A moderated mediation framework explaining the paradoxical tension–performance relationship. Long Range Planning, 53(1), 101863. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2018.12.003

Reinecke, J., & Ansari, S. (2015). When times collide: Temporal brokerage at the intersection of markets and developments. Academy of Management Journal, 58(2), 618–648. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2012.1004