Abstract

Metanormativists hold that moral uncertainty can affect how we ought, in some morally authoritative sense, to act. Many metanormativists aim to generalize expected utility theory for normative uncertainty. Such accounts face the “easy problem of intertheoretic comparisons”: the worry that distinct theories’ assessments of choiceworthiness are incomparable. The easy problem may well be resolvable, but another problem looms: while some moral theories assign cardinal degrees of choiceworthiness, other theories’ choiceworthiness assignments are merely ordinal. Expected choiceworthiness over such theories is undefined. Call this the “hard problem of intertheoretic comparisons.” This paper argues that to solve the hard problem, we should model moral theories with imprecise choiceworthiness. Imprecise choiceworthiness assignments can model incomplete cardinal information about choiceworthiness, with precise cardinal choiceworthiness and merely ordinal choiceworthiness as limiting cases. Generalizing familiar decision theories for imprecise choiceworthiness to the case of moral uncertainty generates puzzles, however: natural generalizations seem to require reifying parts of the model that don’t correspond to anything in normative reality. I discuss three ways of addressing this problem: by demystifying the reified elements by using them as promiscuously as possible; by constructing alternative decision theories that don’t require the troublesome elements; and by employing an alternative model of metanormative decision problems, and of moral uncertainty generally.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Metanormativists differ on these finer points.

I use “choiceworthiness” as a generalization of “utility” or “value”, both to avoid the presupposition of utilitarianism or consequentialism and to accommodate the possibility that the relevant quantity may be “subjective”, in the sense of the subjective “ought”.

Metanormative decision theories face other problems that this paper doesn’t address, e.g., problems associated with absolutist theories that apparently assign infinite degrees of choiceworthiness, and with normative uncertainty about metanormative decision theory itself.

More accurately, non-instrumental, comparative desire; cf. Phillips-Brown (forthcoming).

This representation is meant to be neutral between causal and evidential decision theory.

Alternatively, we may assume that the CFs in the metanormative decision theories throughout assign subjective choiceworthiness, already accounting for the relevant state of descriptive uncertainty; see Carr (2020) for discussion. The benefit of this maneuver is that it can incorporate normative uncertainty about (descriptive) decision theory.

But see MacAskill (2014) for objections.

See MacAskill (2016) for discussion of appropriate voting procedures for normative uncertainty across merely ordinal theories.

The strategy ultimately endorsed in MacAskill (2016) is arguably an instance of this method. See Martinez (Unpublished) for discussion and objections.

Some may insist on a distinction between cases where two theories are comparable, but only indeterminately so, vs. cases where two theories are incomparable in some more absolute sense. If these are distinct, there’s an even harder problem to solve than the hard problem. Solving the harder problem is outside the scope of this paper.

Thanks to Krister Bykvist for discussion.

For simplicity I assume precise credences throughout.

For the case of imprecise credences, Joyce (2010) defends (though does not go so far as to endorse) the analogous decision rule.

See Elga (2010) for an extended discussion in the context of imprecise credences.

Weatherson (manuscript) introduces and defends Caprice for imprecise credences.

Intersection maximization, defended by Sen (2004), differs from V-admissibility in reversing its order of quantifiers.

I use \(A, B, \ldots\) as names for acts and lower-case a, with or without primes or subscripts, as variables over acts.

In realistic cases, adequate representors will plausibly require infinitely many members; I use smaller representors for simplicity.

Gilboa & Schmeidler (1993) defend the analogue of this decision rule for imprecise credences.

For a defense of amplified theories and examples, see MacAskill et al. (2020), 125–130.

More precisely, for a set of theories \({\mathcal {T}} = \{t_1, \ldots , t_n\}\), each \(t_i\) has an informationally adequate \(U^{t_i}\). These determine a set of sequences \(U^{t_1} \times \ldots \times U^{t_n}\). For each \({\mathbf {u}}\) in this set, the intertheoretic representor \(U_I\) contains an ICF \(u_I\) such that for all i, \(1 \le i \le n\), and all \(w \in {\mathcal {W}}\), \(u_I(w, t_i) = {\mathbf {u}}_i(w)\).

Objection: Can’t the proponent of intertheoretic representors also use this maneuver, insisting that the relevant form of uncertainty only arises if we haven’t individuated theories finely enough? Reply: This would require decision-theoretically significant distinctions between theories with completely identical choiceworthiness representors.

I assume finitude for simplicity. The relevant n might be determined by the products of the cardinalities of all epistemically possible imprecise choiceworthiness assignments to all epistemically possible outcomes—which may be unwieldy. Because the view presented has a localist spirit, we may not need so great an n in specific contexts to capture the believer’s state of uncertainty.

I assume that the relevant scale for selecting members of super-representors has been fixed. For details on how this is accomplished, see Carr (2020), §3.2 and §4.1.

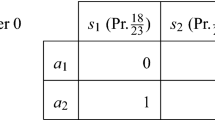

If this looks too similar to intertheoretic uncertainty, we can construct a more localist model. Each hypothesis about the distribution of imprecise choiceworthinesses over options is represented with a matrix. Suppose there are m possible acts in the relevant choice situation with n (possibly redundant) choiceworthiness sharpenings. (I assume purely normative uncertainty for simplicity.) We’ll represent a local hypothesis about imprecise choiceworthinesses with a matrix \(\mathbf{V} \in {\mathbb {R}}^{m \times n}\), where the ith row represents \(a_i\)’s range of imprecise choiceworthiness.

$$\begin{aligned} {\mathbf {V}} = \begin{pmatrix} v_{1,1} &{} v_{1,2} &{} \ldots &{} v_{1,n} \\ v_{2,1} &{} v_{2,2} &{} \ldots &{} v_{2,n} \\ \vdots &{} \vdots &{} \ddots &{} \vdots \\ v_{m,1} &{} v_{m,2} &{} \ldots &{} v_{m,n} \\ \end{pmatrix} \end{aligned}$$Suppose an agent is uncertain \(a_1\)’s choiceworthiness, but certain that \(a_1\) is determinately more choiceworthy than \(a_2\). Then every epistemically possible \({\mathbf {V}}\)’s ith entry for \(a_1\), \(v_{1,i}\), will be greater than its entry for \(a_2\). If the agent is uncertain whether \(a_1\) is determinately more choiceworthy than \(a_2\), then some epistemically possible \({\mathbf {V}}\) won’t have that property.

Each \({\mathbf {V}}\) represents a conjunction of hypotheses about the choiceworthiness of different options. Where \(v_{i,*}\) is the ith row of \({\mathbf {V}}\), we can let \(H({\mathbf {V}})\) be the proposition: \(\mathtt {U}(a_1) = v_{1,*} \wedge \ldots \wedge \mathtt {U}(a_n) = v_{n,*}\).

Then we can define a sequence of expected de dicto choiceworthinesses as follows:

$$\begin{aligned} E\mathtt {u}_j(a_i) = \sum _{{\mathbf {V}} \in {\mathbb {R}}^{n \times m}}cr(H({\mathbf {V}})) \cdot v_{i,j} \end{aligned}$$For each epistemically possible \({\mathbf {V}}\), \(E\mathtt {u}_j(a_i)\) looks at \({\mathbf {V}}\)’s imprecise choiceworthiness for option \(a_i\) and picks out the jth sharpening. \(E\mathtt {u}_j(a_i)\) then takes a weighted average of the possible jth sharpenings, weighted by the probability of each hypothesis V about the distribution of choiceworthinesses across options.

References

Carr, J. R. (2020). Normative uncertainty without theories. Australasian Journal of Philosophy, 98(4), 747–762.

Chang, R. (1997). Incommensurability. Incomparability and practical reason. Harvard University Press.

Doody, R. (2019a). Opaque sweetening and transitivity. Australasian Journal of Philosophy, 97(3), 559–571.

Doody, R. (2019b). Parity, prospects, and predominance. Philosophical Studies, 176(4), 1077–1095.

Elga, A. (2010). Subjective probabilities should be sharp. Philosophers’ Imprint, 10(05)

Gilboa, I., & Schmeidler, D. (1993). Updating ambiguous beliefs. Journal of Economic Theory, 59, 33–49.

Hare, C. (2010). Take the sugar. Analysis, 70(2), 237–247. https://doi.org/10.1093/analys/anp174

Harman, E. (2011). Does moral ignorance exculpate? Ratio, 24(4), 443–468.

Hedden, B. (2016). “Does MITE Make Right? Decision-Making Under Normative Uncertainty.” In Russ Schafer-Landau (ed.), Oxford Studies in Metaethics Vol. 11, 102–128.

Joyce, J. M. (2010). A defense of imprecise credences in inference and decision making. Philosophical Perspectives, 24(1), 281–323.

Levi, I. (1986). Hard choices: decision making under unresolved conflict. Cambridge University Press.

Lockhart, T. (2000). Moral uncertainty and its consequences. Oxford University Press.

MacAskill, W. (2014). Normative uncertainty: University of Oxford dissertation. https://www.academia.edu/8473546/Normative_Uncertainty.

MacAskill, W. (2016). Normative uncertainty as a voting problem. Mind, 125(500), 967–1004.

MacAskill, W., Bykvist, K., & Ord, T. (2020). Moral Uncertainty. Oxford University Press.

Martinez, J. (Unpublished). The Borda Rule and Normative Uncertainty.

Oddie, G. (1994). Moral Uncertainty and Human Embryo Experimentation. In K. W. M. Fulford, G. Gillett & J. M. Soskice (eds.), Medicine and Moral Reasoning, 3–144. Cambridge University Press.

Phillips-Brown, M. (forthcoming). What does decision theory have to do with wanting?” Mind .

Ross, J. (2006). Rejecting ethical deflationism. Ethics, 116(4), 742–768.

Schoenfield, M. (2014). Decision making in the face of parity. Philosophical Perspectives, 28(1), 263–277. https://doi.org/10.1111/phpe.12044

Sen, A. (2004). Incompleteness and reasoned choice. Synthese, 140(1–2), 43–59. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:SYNT.0000029940.51537.b3

Sepielli, A. (2009). What to Do When You Don’t Know What to Do. Oxford Studies in Metaethics, 4, 5–28.

Sepielli, A. (2013). Moral uncertainty and the principle of equity among moral theories. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 86(3), 580–589.

Tarsney, C. (2018). Intertheoretic value comparison: a modest proposal. Journal of Moral Philosophy, 15, 324–344.

Weatherson, B. (manuscript). Decision Making with Imprecise Probabilities.

Acknowledgements

Enormous thanks to Krister Bykvist, Graham Oddie, Chip Sebens, and audiences at CalTech and the Boulder Formal Value Theory Workshop. Special thanks to Ryan Doody and Melissa Fusco for lengthy discussion.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Carr, J.R. The hard problem of intertheoretic comparisons. Philos Stud 179, 1401–1427 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-021-01712-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-021-01712-2