- 1Psychology Research Laboratory, Istituto Auxologico Italiano IRCCS, Verbania, Italy

- 2Department of Psychology, Catholic University of Milan, Milano, Italy

- 3Faculty of Psychology, eCampus University, Novedrate, Italy

Treating mental disorders is a critical issue for modern societies due to high costs for the different national healthcare systems. Evidence-based psychological therapies and structured psychotherapies have been recommended for common mental health problems, but real provision of them has not yet achieved significant spread and impact (Mukuria et al., 2013).

To improve access to psychological therapies may provide cost-effective solutions, since their positive long-term impact on health has been largely demonstrated (Castelnuovo, 2010a,b; Campbell et al., 2013; Dezetter et al., 2013; Mukuria et al., 2013; Emmelkamp et al., 2014).

However, in many developed countries, such as France or Italy, psychotherapies are not enough covered and promoted by the national healthcare systems and health insurance companies (Dezetter et al., 2013).

Differently, in the UK, to tackle the huge problem of mental illness, a comprehensive programme of psychological therapy has been launched and watched worldwide.

An estimation of its long-term clinical and economic benefits, has, in fact, led to ascertain that “psychological therapy costs nothing” (Layard and Clark, 2014; Clark and Layard, 2015).

In order to mimic the positive experience developed in the UK, other countries have now to demonstrate not only the fundamental role and scientific validity of psychological treatments in both clinical and health settings, but also their significant cost-efficacy.

As noted by Emmelkamp et al. (2014), “There is little doubt from a scientific perspective that psychotherapy according to this definition is effective, highly beneficial and cost-effective for a wide range of mental disorders and health conditions, such as anxiety, stress and trauma-related disorders, depressive and somatoform and pain disorders, personality disorder, substance use disorders and behavioral addictions, eating disorders and a number of childhood disorders. For all these disorders, various variants of CBT have been established in clinical randomized trials” (pp. 66, 67), but research in psychotherapy lacks of cost-benefit analysis of interventions: “even if a psychological treatment could show strong efficacy and/or effectiveness, due to high costs it might never be assimilated in real clinical practice” (p. 67, Emmelkamp et al., 2014).

Unfortunately, most clinical psychologists and psychotherapists are not willing to measure the impact of their clinical practice, even if Beutler (2009) underlined that the gap existing between science and practice could be more imputed to scientists' attitude than to practitioners' intransigence: “scientists were intentionally obscuring many important results because of an unwarranted devotion to a limited number of scientific methods. In fact, I came to believe that they may be using methods and defining psychotherapy and research informed practice in ways that hindered clinicians from being optimally effective” (p. 301, Beutler, 2009).

Considering that psychological therapies should be studied not only in the narrow frame of Empirically Supported Treatments (ESTs) approach, but also using different and integrated research and statistical methods (Beutler, 2009), their cost-effectiveness demonstration remains an unaddressed issue in the psychotherapy field. Indeed, as argued by Lilienfeld et al. (2013) with references to how to promote new evidence-based psychological treatments, “organizational support is often tied to the perceived financial viability of a new treatment (Nelson et al., 2006). Consequently, in order to obtain financial support for learning new approaches and techniques within a clinical context, professionals must first estimate and prove the economic gain of training courses to funding organizations. Treatments that have not demonstrated (or treatments whose cost-effectiveness have not been explored) are therefore less viable options for organizations to support” (p. 895, Lilienfeld et al., 2013).

More clinical studies aimed at providing cost-offset estimations also measuring additional intangible benefits and showing that psychological treatments could be effective, at both clinical and economic levels, are thus necessary (Wunsch et al., 2014).

It is important not to confuse a necessary cost-effective approaches in psychotherapy with dangerous cheap performances provided by the mental health practitioners: “while cost-effective treatments can yield savings in healthcare costs, disability claims, and other societal costs, cost-effective by no means translates to cheap but instead describes treatments that are clinically effective and provided at a cost that is considered reasonable given the benefit they provide, even if the treatments increase direct expenses” (p. 423, Lazar, 2014).

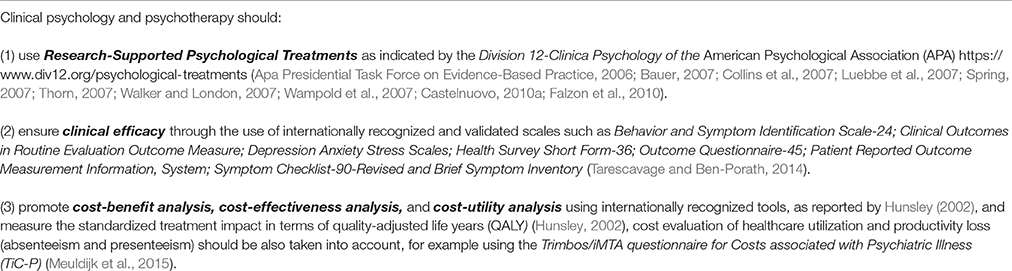

In clinical psychology, standardized, and internationally recognized psychotherapeutic outcome measures have therefore been developed in order to demonstrate patient improvements (Tarescavage and Ben-Porath, 2014), and an ample set of measurements that are useful to evaluate patients outcomes is currently available considering different criteria (administration time and cost, psychometrics and sensitivity to change, etc.). Among these, the Behavior and Symptom Identification Scale-24 (BASIS-24); the Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation Outcome Measure (CORE-OM); the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS); the Health Survey Short Form-36 (SF-36); the Outcome Questionnaire-45 (OQ-45); the Patient Reported Outcome Measurement Information System (PROMIS); the Symptom Checklist-90-Revised (SCL-90-R); and the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) (Tarescavage and Ben-Porath, 2014) are just a few.

However, no agreement has been yet reached over what constitutes relevant ad universal measurements in psychopathology, as requested by the International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement (ICHOM) (Porter et al., 2016). Also, clinical psychologists and researchers should strive to develop standardized sets of measures able to estimate savings costs of psychological treatments.

In this regard, commonly used analytic approaches to obtain economic evaluations of health care services are: (1) cost-benefit analysis (focusing on the socially desirable outcome achieved by a particular treatment), (2) cost-effectiveness analysis (taking into account the relationship between monetary costs and measures of treatment outcome, evaluating a possible symptoms reduction or a growing work productivity), (3) cost-utility analysis (with similar features of the cost-effectiveness analysis but using a valuing metric for measuring the treatment impact standardized in terms of quality-adjusted life years—QALY). Considering not only the clinical efficacy of ESTs, but also the number of years of life in which an individual would be expected to be completely free of symptoms or disability is a key point to persuade policy makers and administrators that allocation of resources to psychological interventions would lead to both clinical and economic advantages (Hunsley, 2002).

Taking into account that the future of the health care systems will be the promising stepped care approach for both chronic care pathologies (Davison, 2000; Richards et al., 2003, 2012; Hermens et al., 2014; Castelnuovo et al., 2015a,b; Delgadillo et al., 2015) and mental disorders (Richards, 2012; Watzke et al., 2014; Gidding et al., 2015; Gureje et al., 2015; Haug et al., 2015; Manber et al., 2015; Oladeji et al., 2015; Palmer et al., 2015; Paris, 2015; Salloum et al., 2015; Edelman et al., 2016), clinical psychologists will play a key role in delivering positive outcomes by continuously revising and progressively intensifying the therapeutic process through the reduction of costs.

Despite evidence of the efficacy and effectiveness of the stepped care approach in the clinical field has not been yet reached, positive results have been obtained for preventive treatments aimed at reducing subthreshold depression, which used Internet for individuals who were not able to take part in group interventions (Munoz et al., 1995; Willemse et al., 2004; Van't Veer-Tazelaar et al., 2009; Cuijpers et al., 2010). Instead, another recent study (Van Beljouw et al., 2015) evaluating an outreaching stepped care program on depressive symptoms in older adults failed to demonstrate the utility of the model, while revealing a single (and not stepped) treatment chosen by the participants being sufficient to achieve positive clinical outcomes.

Still, further evidence of the cost-benefit, cost-effectiveness, and cost-utility of both single and stepped care approaches in clinical psychology are needed. Useful indications suggesting how to legitimize clinical psychology in health care system are provided in Table 1.

Future research in psychology and psychotherapy should, therefore, focus more on cost-effective solutions for the treatment of mental disorders, also considering opportunities provided by new technologies (Castelnuovo et al., 2003, 2014; Cartreine et al., 2010; Castelnuovo and Simpson, 2011; Andrews and Williams, 2014).

Author Contributions

All authors listed, have made substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The author(s) received no financial support for the authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

Andrews, G., and Williams, A. D. (2014). Internet psychotherapy and the future of personalized treatment. Depress. Anxiety 31, 912–915. doi: 10.1002/da.22302

Apa Presidential Task Force on Evidence-Based Practice (2006). Evidence-based practice in psychology. Am. Psychol. 61, 271–285. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.61.4.271

Bauer, R. M. (2007). Evidence-based practice in psychology: implications for research and research training. J. Clin. Psychol. 63, 685–694. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20374

Beutler, L. E. (2009). Making science matter in clinical practice: redefining psychotherapy. Clin. Psychol. 16, 301–317. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2850.2009.01168.x

Campbell, L. F., Norcross, J. C., Vasquez, M. J., and Kaslow, N. J. (2013). Recognition of psychotherapy effectiveness: the APA resolution. Psychotherapy 50, 98–101. doi: 10.1037/a0031817

Cartreine, J. A., Ahern, D. K., and Locke, S. E. (2010). A roadmap to computer-based psychotherapy in the United States. Harv. Rev. Psychiatry 18, 80–95. doi: 10.3109/10673221003707702

Castelnuovo, G. (2010a). Empirically supported treatments in psychotherapy: towards an evidence-based or evidence-biased psychology in clinical settings? Front. Psychol. 1:27. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2010.00027

Castelnuovo, G. (2010b). No medicine without psychology: the key role of psychological contribution in clinical settings. Front. Psychol. 1:4. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2010.00004

Castelnuovo, G., and Simpson, S. (2011). Ebesity - e-health for obesity - new technologies for the treatment of obesity in clinical psychology and medicine. Clin. Pract. Epidemiol. Ment. Health 7, 5–8. doi: 10.2174/1745017901107010005

Castelnuovo, G., Gaggioli, A., Mantovani, F., and Riva, G. (2003). From psychotherapy to e-therapy: the integration of traditional techniques and new communication tools in clinical settings. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 6, 375–382. doi: 10.1089/109493103322278754

Castelnuovo, G., Manzoni, G. M., Pietrabissa, G., Corti, S., Giusti, E. M., Molinari, E., et al. (2014). Obesity and outpatient rehabilitation using mobile technologies: the potential mHealth approach. Front. Psychol. 5:559. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00559

Castelnuovo, G., Pietrabissa, G., Manzoni, G. M., Corti, S., Ceccarini, M., Borrello, M., et al. (2015a). Chronic care management of globesity: promoting healthier lifestyles in traditional and mHealth based settings. Front. Psychol. 6:1557. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01557

Castelnuovo, G., Zoppis, I., Santoro, E., Ceccarini, M., Pietrabissa, G., Manzoni, G. M., et al. (2015b). Managing chronic pathologies with a stepped mHealth-based approach in clinical psychology and medicine. Front. Psychol. 6:407. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00407

Clark, D., and Layard, R. (2015). Why more psychological therapy would cost nothing. Front. Psychol. 6:1713. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01713

Collins, F. L. Jr., Leffingwell, T. R., and Belar, C. D. (2007). Teaching evidence-based practice: implications for psychology. J. Clin. Psychol. 63, 657–670. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20378

Cuijpers, P., Van Straten, A., Warmerdam, L., and Van Rooy, M. J. (2010). Recruiting participants for interventions to prevent the onset of depressive disorders: possible ways to increase participation rates. BMC Health Serv. Res. 10:181. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-181

Davison, G. C. (2000). Stepped care: doing more with less? J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 68, 580–585. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.68.4.580

Delgadillo, J., Gellatly, J., and Stephenson-Bellwood, S. (2015). Decision making in stepped care: how do therapists decide whether to prolong treatment or not? Behav. Cogn. Psychother. 43, 328–341. doi: 10.1017/S135246581300091X

Dezetter, A., Briffault, X., Ben Lakhdar, C., and Kovess-Masfety, V. (2013). Costs and benefits of improving access to psychotherapies for common mental disorders. J. Ment. Health Policy Econ. 16, 161–177.

Edelman, E. J., Hansen, N. B., Cutter, C. J., Danton, C., Fiellin, L. E., O'connor, P. G., et al. (2016). Implementation of integrated stepped care for unhealthy alcohol use in HIV clinics. Addict. Sci. Clin. Pract. 11, 1. doi: 10.1186/s13722-015-0048-z

Emmelkamp, P. M., David, D., Beckers, T., Muris, P., Cuijpers, P., Lutz, W., et al. (2014). Advancing psychotherapy and evidence-based psychological interventions. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 23(Suppl. 1), 58–91. doi: 10.1002/mpr.1411

Falzon, L., Davidson, K. W., and Bruns, D. (2010). Evidence searching for evidence-based psychology practice. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pr. 41, 550–557. doi: 10.1037/a0021352

Gidding, L. G., Spigt, M. G., Maris, J. G., Herijgers, O., and Dinant, G. J. (2015). Shifts in the care for patients presenting in primary care with anxiety; stepped collaborative care parameters from more than a decade. Eur. Psychiatry 30, 770–777. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2015.06.002

Gureje, O., Oladeji, B. D., Araya, R., and Montgomery, A. A. (2015). A cluster randomized clinical trial of a stepped care intervention for depression in primary care (STEPCARE)–study protocol. BMC Psychiatry 15:148. doi: 10.1186/s12888-015-0542-6

Haug, T., Nordgreen, T., Ost, L. G., Kvale, G., Tangen, T., Andersson, G., et al. (2015). Stepped care versus face-to-face cognitive behavior therapy for panic disorder and social anxiety disorder: predictors and moderators of outcome. Behav. Res. Ther. 71, 76–89. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2015.06.002

Hermens, M. L., Muntingh, A., Franx, G., Van Splunteren, P. T., and Nuyen, J. (2014). Stepped care for depression is easy to recommend, but harder to implement: results of an explorative study within primary care in the Netherlands. BMC Fam. Pract. 15:5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-15-5

Hunsley, J. (2002). The Cost-Effectiveness of Psychological Interventions. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Psychological Association.

Layard, R., and Clark, D. M. (2014). Thrive: The Power of Evidence-Based Psychological Therapies. London: Penguin.

Lazar, S. G. (2014). The cost-effectiveness of psychotherapy for the major psychiatric diagnoses. Psychodyn. Psychiatry 42, 423–457. doi: 10.1521/pdps.2014.42.3.423

Lilienfeld, S. O., Ritschel, L. A., Lynn, S. J., Cautin, R. L., and Latzman, R. D. (2013). Why many clinical psychologists are resistant to evidence-based practice: root causes and constructive remedies. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 33, 883–900. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2012.09.008

Luebbe, A. M., Radcliffe, A. M., Callands, T. A., Green, D., and Thorn, B. E. (2007). Evidence-based practice in psychology: perceptions of graduate students in scientist-practitioner programs. J. Clin. Psychol. 63, 643–655. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20379

Manber, R., Simpson, N. S., and Bootzin, R. R. (2015). A step towards stepped care: delivery of CBT-I with reduced clinician time. Sleep Med. Rev. 19, 3–5. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2014.09.003

Meuldijk, D., Carlier, I. V., Van Vliet, I. M., Van Hemert, A. M., Zitman, F. G., and Van Den Akker-Van Marle, M. E. (2015). Economic evaluation of concise cognitive behavioural therapy and/or pharmacotherapy for depressive and anxiety disorders. J. Ment. Health Policy Econ. 18, 175–183.

Mukuria, C., Brazier, J., Barkham, M., Connell, J., Hardy, G., Hutten, R., et al. (2013). Cost-effectiveness of an improving access to psychological therapies service. Br. J. Psychiatry 202, 220–227. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.107888

Munoz, R. F., Ying, Y. W., Bernal, G., Perez-Stable, E. J., Sorensen, J. L., Hargreaves, W. A., et al. (1995). Prevention of depression with primary care patients: a randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Community Psychol. 23, 199–222.

Nelson, T. D., Steele, R. G., and Mize, J. A. (2006). Practitioner attitudes toward evidence-based practice: themes and challenges. Adm. Policy Ment. Health 33, 398–409. doi: 10.1007/s10488-006-0044-4

Oladeji, B. D., Kola, L., Abiona, T., Montgomery, A. A., Araya, R., and Gureje, O. (2015). A pilot randomized controlled trial of a stepped care intervention package for depression in primary care in Nigeria. BMC Psychiatry 15:96. doi: 10.1186/s12888-015-0483-0

Palmer, V. J., Chondros, P., Piper, D., Callander, R., Weavell, W., Godbee, K., et al. (2015). The CORE study protocol: a stepped wedge cluster randomised controlled trial to test a co-design technique to optimise psychosocial recovery outcomes for people affected by mental illness in the community mental health setting. BMJ Open 5:e006688. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006688

Paris, J. (2015). Stepped care and rehabilitation for patients recovering from borderline personality disorder. J. Clin. Psychol. 71, 747–752. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22202

Porter, M. E., Larsson, S., and Lee, T. H. (2016). Standardizing patient outcomes measurement. N. Engl. J. Med. 374, 504–506. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1511701

Richards, D. A. (2012). Stepped care: a method to deliver increased access to psychological therapies. Can. J. Psychiatry 57, 210–215.

Richards, D. A., Bower, P., Pagel, C., Weaver, A., Utley, M., Cape, J., et al. (2012). Delivering stepped care: an analysis of implementation in routine practice. Implement. Sci. 7:3. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-7-3

Richards, D. A., Lovell, K., and Mcevoy, P. (2003). Access and effectiveness in psychological therapies: self-help as a routine health technology. Health Soc. Care Community 11, 175–182. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2524.2003.00417.x

Salloum, A., Wang, W., Robst, J., Murphy, T. K., Scheeringa, M. S., Cohen, J. A., et al. (2015). Stepped care versus standard trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy for young children. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 57, 614–622. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12471

Spring, B. (2007). Evidence-based practice in clinical psychology: what it is, why it matters; what you need to know. J. Clin. Psychol. 63, 611–631. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20373

Tarescavage, A. M., and Ben-Porath, Y. S. (2014). Psychotherapeutic outcomes measures: a critical review for practitioners. J. Clin. Psychol. 70, 808–830. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22080

Thorn, B. E. (2007). Evidence-based practice in psychology. J. Clin. Psychol. 63, 607–609. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20384

Van Beljouw, I. M., Van Exel, E., Van De Ven, P. M., Joling, K. J., Dhondt, T. D., Stek, M. L., et al. (2015). Does an outreaching stepped care program reduce depressive symptoms in community-dwelling older adults? A randomized implementation trial. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 23, 807–817. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2014.09.012

Van't Veer-Tazelaar, P. J., Van Marwijk, H. W., Van Oppen, P., Van Hout, H. P., Van Der Horst, H. E., Cuijpers, P., et al. (2009). Stepped-care prevention of anxiety and depression in late life: a randomized controlled trial. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 66, 297–304. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2008.555

Walker, B. B., and London, S. (2007). Novel tools and resources for evidence-based practice in psychology. J. Clin. Psychol. 63, 633–642. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20377

Wampold, B. E., Goodheart, C. D., and Levant, R. F. (2007). Clarification and elaboration on evidence-based practice in psychology. Am. Psychol. 62, 616–618. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X62.6.616

Watzke, B., Heddaeus, D., Steinmann, M., Konig, H. H., Wegscheider, K., Schulz, H., et al. (2014). Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of a guideline-based stepped care model for patients with depression: study protocol of a cluster-randomized controlled trial in routine care. BMC Psychiatry 14:230. doi: 10.1186/s12888-014-0230-y

Willemse, G. R., Smit, F., Cuijpers, P., and Tiemens, B. G. (2004). Minimal-contact psychotherapy for sub-threshold depression in primary care. Randomised trial. Br. J. Psychiatry 185, 416–421. doi: 10.1192/bjp.185.5.416

Keywords: psychological therapy, cost-effectiveness, evidence-based psychological therapies, evidence-based psychotherapy, evidence based in clinical psychology, mental health burden, psychotherapy

Citation: Castelnuovo G, Pietrabissa G, Cattivelli R, Manzoni GM and Molinari E (2016) Not Only Clinical Efficacy in Psychological Treatments: Clinical Psychology Must Promote Cost-Benefit, Cost-Effectiveness, and Cost-Utility Analysis. Front. Psychol. 7:563. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00563

Received: 05 January 2016; Accepted: 05 April 2016;

Published: 09 May 2016.

Edited by:

Omar Carlo Gioacchino Gelo, Università del Salento, Italy and Sigmund Freud University, AustriaReviewed by:

Alessandro Capucci, Universita' Politecnica delle Marche, ItalyHarm Van Marwijk, University of Manchester, UK

Copyright © 2016 Castelnuovo, Pietrabissa, Cattivelli, Manzoni and Molinari. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Gianluca Castelnuovo, gianluca.castelnuovo@auxologico.it; gianluca.castelnuovo@unicatt.it

Gianluca Castelnuovo

Gianluca Castelnuovo Giada Pietrabissa

Giada Pietrabissa Roberto Cattivelli

Roberto Cattivelli Gian Mauro Manzoni

Gian Mauro Manzoni Enrico Molinari

Enrico Molinari