Article contents

The Defence of Olynthus

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 11 February 2009

Extract

Demosthenes prophesied1 that, unless Athens stopped Philip in the north, she would have to deal with him in Greece itself, and the events of 346 proved him right. Right in this much, he has been presumed right in general, and the policies of those he opposed have received only scant consideration before being dismissed as the selfish pursuit of peace by the rich, who were so blinded by their material interests that they could not see the real issues involved. It is the purpose of this article to question, from a purely military standpoint, the soundness of Demosthenes' policy.

- Type

- Research Article

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Classical Association 1962

References

page 122 note 1 I. 25, 3. 8,4. 50.

page 122 note 2 Schaefer, , Demosthenes und seine Zeit, ii 2Google Scholar, speaks of a ‘wretched peace-party and bribed orators’ (p. 51) and ‘der selbstsiichtigen Partei, welche unter Eubulus Leitung den Staat beherrschte’. Schwarz, , ‘Demosthenes erste Philippika’ in Festschrift Theodor Mommsen, speaks of ‘die Partei des Besitzes und die Besitzenden’ (cf. pp. 13, 35, 39, 49)Google Scholar and of ‘die Friedenspartei’. Cf. Cloché, La politique extirieure, p. 219Google Scholar, and Jaeger, , Demosthenes, p. 142 (‘the same rich politicians of the peace party’). The double accusation of pacificism for personal profit is almost communis opinio. The alleged pacificism is, by implication, called in question by this article. What is the ground for supposing that Eubulus and his supporters were rich and the ‘patriots’ poor? Demosthenes likes to talk about the riches of his opponents (e.g. 3. 29) but we do not have their replies. Demosthenes was a rich man himself, and indeed most of ![]() must have been fairly well off.Google Scholar

must have been fairly well off.Google Scholar

page 122 note 3 Op. cit.

page 122 note 4 Ad Amm., pp. 725 and 736.Google Scholar

page 122 note 5 Amongst those who commit themselves Kahrstedt, Forschungen, p. 121, n. 211Google Scholar, Pokorny, , Studien, pp. 125 f.Google Scholar, and Momigliano, , Filippo il Macedone, pp. 110 and 112, n. 1Google Scholar, follow Schwartz. Pickard-Cambridge, , Demosthenes, p. 184Google Scholar, Cloché, , op. cit., p. 203Google Scholar (cf. Un fondateur d'empire, p. 111Google Scholar), and Jacoby, Commentary on Philochorus frag. 47, favour the early date. Jaeger, , Demosthenes, pp. 120 f.Google Scholar, believes in the early date and a later (and so misleading) edition (cf. p. 123, n. 5 below). Focke, , Demosthenesstudien, pp. 21 f.Google Scholar, dates the speech in October 350. Sealey, , R.É.G. Ixviii (1955), 77 f., attempts a general defence of the accuracy of Dionysius' dates for Demosthenes.Google Scholar

page 123 note 1 Dem, . 23. 109.Google Scholar

page 123 note 2 1. 7, 3. 7.

page 123 note 3 Ibid.

page 123 note 4 §2.

page 123 note 5 Jaeger, , op. cit., pp. 120 f., admirably set out reasons for dissociating the speech from the attack on Olynthus in 349, but, believing that the reference to a sudden attack on Olynthus in § 17 must concern the events of 349, explained it as the insertion of a later edition. His promised special study (p. 238, n. 35) has never, as far as I know, appeared. If it is merely a question of choosing between the hypothesis of a later edition and that of an odierwise unattested attack on Olynthus, in view of the nature of the sources the latter is far preferable.Google Scholar

page 124 note 1 Cf. Justin, 3. 8. 11 f. who recounts the fall of Olynthus, then Philip's activities in Thessaly and Thrace, and ends ‘et ne quod ius vel fas inviolatum praetermitteret, piraticam quoque exercere instituit’. It is also to be noted that the decree which Aeschines went on to describe in 2. 73 suits the period of Philip's campaign against Cersobleptes in 346, when Chares was in command at the Hellespont (Aesch. 2. 90).Google Scholar

page 124 note 2 F.G.H. 328 F 47.Google Scholar

page 124 note 3 F.G.H. 324 F 24.Google Scholar

page 124 note 4 Although the landing at Marathon is cited last by Demosthenes in § 34 and prefaced by ![]() it is not clear that it was die latest in time of the events mentioned. As Jacoby pointed out (Commentary on Androt. frag. 24), the order is perhaps deliberately geographical and

it is not clear that it was die latest in time of the events mentioned. As Jacoby pointed out (Commentary on Androt. frag. 24), the order is perhaps deliberately geographical and ![]() may simply denote ‘the crowning instance of Philip's privateering’. What is clear from Androtion is that Philip was active with piratical raids earlier than the Olynthian war.

may simply denote ‘the crowning instance of Philip's privateering’. What is clear from Androtion is that Philip was active with piratical raids earlier than the Olynthian war.

page 124 note 5 Schwartz, , op. cit., p. 34, also related the reference in § 37 to the troubles in Euboea in 349/8. However, Philip does not appear to have been involved in these troubles (cf. section II of this article) and the letters cannot be dated.Google Scholar

page 124 note 6 Op. cit., p. 31.Google Scholar

page 125 note 1 Op. cit., p. 30.Google Scholar

page 125 note 2 The speech On the Liberty of the Rhodians is dated to 351/0 by Dionysius of Halicarnassus, , ad Amm. p. 726Google Scholar, under which year Diodorus (16. 40) set the Persian attack on Egypt alluded to in § 11 of the speech. Since the date of the Persian attack must have been readily available in what Dionysius calls the ![]() (ad Amm. pp. 724 and 740Google Scholar), 351/0 is commonly accepted as the date of the speech. Focke, , op. cit., pp. 18 f.Google Scholar, tried to upset this largely with regard to the dates of the dynasty of Caria (cf. §§ 11 and 27 of the speech), but see Kahrstedt, , op. cit., pp. 22 f.Google Scholar

(ad Amm. pp. 724 and 740Google Scholar), 351/0 is commonly accepted as the date of the speech. Focke, , op. cit., pp. 18 f.Google Scholar, tried to upset this largely with regard to the dates of the dynasty of Caria (cf. §§ 11 and 27 of the speech), but see Kahrstedt, , op. cit., pp. 22 f.Google Scholar

page 125 note 3 For date of Philip's attack on Heraeum Teichoscf. Hammond, , J.H.S. lvii (1937), 57.Google Scholar

page 125 note 4 Diod, . 16. 40. 1.Google Scholar

page 125 note 5 Cf. Histoire grecque, iii. 200.Google Scholar

page 125 note 6 Demosthenes‘ speech, On the Symmories, dated to 354/3 by Dionysius (ad Amm. pp. 724–5)Google Scholar, dealt with the danger of Persian attack. Beloch‘s rejection of this date (Gr. Gesch. iii. 2. 261Google Scholar) rests on his dating of Pammenes’ mission to 354 and is not justified (cf. Hammond, , op. cit., pp. 58 f.Google Scholar). The Persian preparations, the rumour of which occasioned Demosthenes' speech, may well have been the first step towards invading Egypt. The Persian force which wrested from Sparta the supremacy of the sea at Cnidus in 394 was being collected in 397/6 (Xen, . Hell. 3. 4. 1).Google Scholar

page 125 note 7 Aesch, . 2. 14.Google Scholar

page 125 note 8 Aesch, . 2. 55, and 110 f.Google Scholar

page 125 note 9 Op. cit., pp. 21 ff., esp. p. 25.Google Scholar

page 126 note 1 § 17. Cf. Dem, . 3. 4 f. The date is probable, if not certain.Google Scholar

page 126 note 2 Cf. § 1. Of course, Demosthenes would be speaking in relation to a ![]() concerning

concerning ![]() (§ 14), but what he means is that the situation has not been changed by some new development.

(§ 14), but what he means is that the situation has not been changed by some new development.

page 126 note 3 Presumably this is the meaning of![]() in Dem. 3. 5. By the law of Periander trierarchs ceased to be responsible for finding their own crews (Dem, . 21. 155Google Scholar), but the

in Dem. 3. 5. By the law of Periander trierarchs ceased to be responsible for finding their own crews (Dem, . 21. 155Google Scholar), but the![]() must on occasion have provided no citizens

must on occasion have provided no citizens![]() and thus left the general to find his own crews entirely. Cf. the contrast in Philochorus, , F.G.H. 328 F 49 between the ships of Chares and

and thus left the general to find his own crews entirely. Cf. the contrast in Philochorus, , F.G.H. 328 F 49 between the ships of Chares and![]() Google Scholar

Google Scholar

page 126 note 4 Ad Amm., p. 725.Google Scholar

page 126 note 5 Three manuscripts have ![]() and two

and two ![]() and the emendation of Boehneck,

and the emendation of Boehneck, ![]() changed by Morell to

changed by Morell to ![]() has found general acceptance.

has found general acceptance.

page 126 note 6 Dem, . 3. 5.Google Scholar

page 126 note 7 Cf. Sealey, , R.É.G. lxviii (1955), 77 f.Google Scholar

page 126 note 8 See n. 6 above.

page 126 note 9 Cf. P.-W. vi. 1. 714.Google ScholarFocke, , op. cit., p. 10, suggested that the date of Charidemus' expedition was related to the Etesians.Google Scholar

page 127 note 1 The Great Mysteries ended on 22 Boedromion (Deubner, , Att. Feste, p. 72), and the Etesians would have ceased earlier, but, if Philip had not acted under cover of die season, there would have no longer been need for haste. If the debate to which the first Philippic belongs was held not long before the Etesians, there was good reason for the haste of ![]() (§ 14). It should be added, however, that Demosthenes' allusion to the Etesians (§31) does not suggest that Philip may shortly exploit the seasons.Google Scholar

(§ 14). It should be added, however, that Demosthenes' allusion to the Etesians (§31) does not suggest that Philip may shortly exploit the seasons.Google Scholar

page 127 note 2 Ad Amm., pp. 724 and 740.Google Scholar

page 127 note 3 J.H.S. xlix (1929), 246 f.Google Scholar Parke follows Kahrstedt, , op. cit., pp. 56 f., in postulating two expeditions, aldiough he differs in detail.Google Scholar

page 127 note 4 e.g. Momigliano, , Filippo il Macedone, p. 111, n. 1Google Scholar, and Cloché, , Unfondateur d'Empire, pp. 131 f.Google Scholar

page 128 note 1 Cf. Thuc, . 8. 16, 22, 32Google Scholar, Xen, . Hell. 2. i. 18, 4. 5. 19.Google Scholar

page 128 note 2 3. 86.

page 128 note 3 Aesch, . 2. 169.Google Scholar

page 129 note 1 Schaefer, , op. cit. ii 2. 82, is probably right in supposing that the news about Tamynae arrived in the course of the![]()

![]() Google Scholar

Google Scholar

page 129 note 2 Plut, . Phoc. 12. 3Google Scholar, Dem, . 21. 132, 133.Google Scholar

page 129 note 3 Dem, . 21. 164 (cf. 132) and 197.Google Scholar

page 129 note 4 Cf. Beloch, , Gr. Gesch. iii. 2. 278 f.Google Scholar

page 129 note 5 So Demosthenes stayed to produce his chorus and was subsequently charged by Midias with desertion (Dem, . 21. 110).Google Scholar

page 129 note 6 Op. cit., pp. 132 f.Google Scholar

page 129 note 7 e.g. Pickard-Cambridge, , op. cit., pp. 208 f.Google Scholar; Beloch, , Gr. Gesch. iii. 1. 495 n. 1Google Scholar, Histoire, grecque, iii. 135Google Scholar; Cloche, , op. cit., p. 135.Google Scholar

page 129 note 8 Dem, . 5. 5.Google Scholar

page 129 note 9 Dem, . 4. 37.Google Scholar

page 129 note 10 Beloch, , loc. cit.Google Scholar, regards Plutarch's introduction here as decisive confirmation of themanuscripts' reading in Aesch, . 3. 87Google Scholar, but in view of the later connexion of Cleitarchus and Philip (Dem, . 9. 58, etc.Google Scholar) it is not surprising that Plutarch should write inaccurately.

page 130 note 1 9. 57 f., 19. 83, 87, 204. Cf. Schaefer, , op. cit. ii 2. 81, n. 2Google Scholar, who rejects the possibility of Philip actually sending help but keeps the manuscript reading in Aesch, . 3. 87, and dismisses Aeschines' account as ‘lügenhaft’.Google Scholar

page 130 note 2 Aesch, . 2. 12.Google Scholar

page 130 note 3 F.G.H. 328 F 49–51.Google Scholar

page 130 note 4 Diod, . 16. 55Google Scholar, Dem, . 19. 192![]()

![]() Google Scholar

Google Scholar

page 130 note 5 Cf. the narrative of Arrian, , Anab. 1. 10 and 11. 1.Google Scholar For the Macedonian Olympia see P.-W. xviii. 1. 46.Google Scholar The usual view is that Olynthus fell during the Greek Olympia (cf. Beloch, , Gr. Gesch. iii. 2. 280Google Scholar), but neither does this allow sufficient time for the events of Aesch, . 2. 12 f.Google Scholar nor is there any reason to suppose that the Greek Olympia were celebrated in Macedon also. Cf. R.É.G. lxxiii (1960), 417, n. 2.Google Scholar

page 130 note 6 19. 266, presumably more or less correct if not exact. The fact that Diodorus (see p. 132, n. 7) splits the war into two archon years does not affect the question of the accuracy of Demosthenes' statement as to the duration of the war.

page 130 note 7 F.G.H. 328 F 49![]()

![]() (The lacuna of about eighteen letters does not affect the close connexion between the making of alliance and the dispatch of the expedition.)Google Scholar

(The lacuna of about eighteen letters does not affect the close connexion between the making of alliance and the dispatch of the expedition.)Google Scholar

page 130 note 8 Cf. Commentary, to Philochorus, , p. 532, lines 9 f.Google Scholar

page 131 note 1 Cf. Scholiast, to Dem, . 2. 1Google Scholar (Dindorf, , viii. 74, line 10Google Scholar), quoted by Jacoby, , F.G.H. iii B, p. 113 (i.e. beneath F 49 and 50).Google Scholar

page 131 note 2 ‘Suidas’, s.v. ![]()

page 131 note 3 F.G.H. 328 F 50.Google Scholar

page 131 note 4 Dem, . 21. 197.Google Scholar

page 131 note 5 Those who, like Kahrstedt, , op. cit., p. 61Google Scholar, place the third expedition in spring 348 do so because they suppose that Olynthus fell at the time of the Greek Olympia. For the whole question of the dating of the expeditions cf. Schaefer, , op. cit. ii 2. 118 f.Google Scholar

page 131 note 6 Cf. Schaefer, , op. cit. ii 2. 76 n. 4.Google Scholar

page 131 note 7 21. 161.

page 131 note 8 It is not clear whether Chares was in Athens to go with these reinforcements. The explanation commonly given of the haste with which he sought to render account of his conduct of the Olynthian war (Dion, . Hal. ad Amm., p. 734Google Scholar, and Ar, . Rhet. 1411aGoogle Scholar) is that he was hurrying to get off with the last expedition. Cf. Schaefer, , op. cit. ii 2. 143.Google Scholar

page 131 note 9 Accame, , La lega ateniese, p. 196, took the mention of syntaxeis in line 13 of fragment b ![]() to refer to an earlier period, because Mytilene was not in the Athenian Confederacy in 349/8, but the phrase could well refer to the other cities of the island that remained in the Confederacy in that year, and although the inscription is too fragmentary to allow of certainty, the various matters touched on in fragment b ap- pear to be concerned with operations in progress. Until fragment a is rediscovered, doubt will remain as to whether fragments b, c, and d really belong to it, but the considerations advanced in the editio minor of I.G. seem sufficient.Google Scholar

to refer to an earlier period, because Mytilene was not in the Athenian Confederacy in 349/8, but the phrase could well refer to the other cities of the island that remained in the Confederacy in that year, and although the inscription is too fragmentary to allow of certainty, the various matters touched on in fragment b ap- pear to be concerned with operations in progress. Until fragment a is rediscovered, doubt will remain as to whether fragments b, c, and d really belong to it, but the considerations advanced in the editio minor of I.G. seem sufficient.Google Scholar

page 132 note 1 The troubles in Euboea continued almost until the Olympic truce of 348 (Aesch, . 2. 12Google Scholar). Presumably the recall of Phocion (Plut, . Phoc. 14. 1Google Scholar) was connected with the subject of I.G. ii 2. 207.Google Scholar

page 132 note 2 Cf. Focke, , op. cit., p. 23 n. 38.Google Scholar

page 132 note 3 Philochorus, , frag. 50.Google Scholar

page 132 note 4 Diod, . 16. 53.Google Scholar

page 132 note 5 Philochorus, , frag. 51.Google Scholar

page 132 note 6 Cf. Dem, . 1.4 … ![]()

![]() Also 9. 11, 8. 59, and 2. 1.Google Scholar

Also 9. 11, 8. 59, and 2. 1.Google Scholar

page 132 note 7 The account of Diodorus gives the attack on Olynthus in two stages. In 16. 52. 9 under 349/8 he records the destruction of ![]() (probably a corruption of

(probably a corruption of ![]() and the subjection of other places. In 16. 53 under 348/7 Philip

and the subjection of other places. In 16. 53 under 348/7 Philip ![]() attacks and captures Torone, Mecyberna, and Olynthus. Thus Diodorus' account is perhaps chronologically correct, is consistent with the situation in the first Olynthiac (cf. § 17, where the aim is said to be ‘to save the cities for the Olynthians’), confirms that Olynthus was not immediately besieged, and reflects the two stages of Philip‘s expressed intentions.

attacks and captures Torone, Mecyberna, and Olynthus. Thus Diodorus' account is perhaps chronologically correct, is consistent with the situation in the first Olynthiac (cf. § 17, where the aim is said to be ‘to save the cities for the Olynthians’), confirms that Olynthus was not immediately besieged, and reflects the two stages of Philip‘s expressed intentions.

The attempt of Focke (op. cit., pp. 10 f.Google Scholar) to date the attack on ![]() in 350 (to which he supposes that Dem. 4. 17 refers) has nothing positive to recommend it. Cf. Momigliano, , op. cit., p. 112, n. 1.Google Scholar The notice about

in 350 (to which he supposes that Dem. 4. 17 refers) has nothing positive to recommend it. Cf. Momigliano, , op. cit., p. 112, n. 1.Google Scholar The notice about ![]() is not inevitably linked with the notice about Pherae (probably a repetition of the notice at Diod, . 16. 37. 3 and 38. 1).Google Scholar

is not inevitably linked with the notice about Pherae (probably a repetition of the notice at Diod, . 16. 37. 3 and 38. 1).Google Scholar

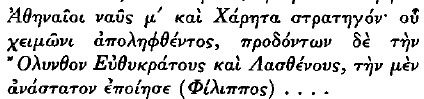

page 132 note 8 It is not clear where the treachery of Lasthenes and Euthycrates (Dem, . 9. 56 and 19. 265 f.Google Scholar) Ills in. One would expect that it belonged to the period of the two battles (Diod, . 16. 53) before the siege began, but Diodorus says that it was the cause of the fall of the city. Perhaps the Greek sources grossly exaggerated or even misrepresented the act of Lasthenes and Euthycrates in surrendering.Google Scholar

page 133 note 1 Cf. 1. 2 and 2. 11.

page 133 note 2 Op. cit., p. 61.Google Scholar

page 133 note 3 Op. cit., pp. 119 f.Google Scholar

page 133 note 4 Cf. Dem, . 3. 10 f.Google Scholar and [Dem, .] 59. 3 f.Google Scholar

page 133 note 5 § 19. ![]()

![]()

page 133 note 6 Focke, , op. cit., pp. 27 f.Google Scholar, errs in the other direction in claiming that, because Demosthenes does not mention Apollodorus, the speech must have been before the latter's proposal.

page 133 note 7 Op. cit., pp. 123 f.Google Scholar

page 133 note 8 The arguments in favour of a long interval between the second and third Olynthiacs have been mustered by Pokorny, , op. cit., pp. 119 f.Google Scholar

page 133 note 9 1. 21 f., 2. 11.

page 133 note 10 § 35.

page 134 note 1 Cf. esp. §§ 1 and 9.

page 134 note 2 Cf. § 25.

page 134 note 3 This would also explain why in the third Olynthiac he has ceased to demand mere ![]() he now saw that only a regular warfund would make possible an expedition of the sort he demanded, and that the difficulty of getting an

he now saw that only a regular warfund would make possible an expedition of the sort he demanded, and that the difficulty of getting an ![]() voted was a brake on sustained major efforts against Philip.

voted was a brake on sustained major efforts against Philip.

page 134 note 4 Cf. Blass, , Attische Beredsamkeit, iii. 1. 320.Google Scholar

page 134 note 5 Momigliano (op. cit., p. 112, n. 1Google Scholar) is a supporter of this view. Its most extreme form is to be found in Erbse, H., Rh. Mus. xcix (1956), 379 f., who supposes that all three Olynthiacs were delivered at one and the same ![]() This both argues an importance of Demosthenes which he probably did not possess, and is a strange notion of Athenian assemblies. (Are there any clear cases known where the same man made two set speeches on the one day on the one subject?) But Erbse's analysis of the speeches effectively shows their close connexion.Google Scholar

This both argues an importance of Demosthenes which he probably did not possess, and is a strange notion of Athenian assemblies. (Are there any clear cases known where the same man made two set speeches on the one day on the one subject?) But Erbse's analysis of the speeches effectively shows their close connexion.Google Scholar

page 134 note 6 As noted above, the first appeal of Olynthus came very early in 349/8, and it was the first matter recorded in Philochorus for that year (cf. p. 130, n. 8), but in view of uncertainty about the procedure of ![]() it would be unsafe to argue from Demosthenes' demand for the appointment of nomothetes (§§ 10 f.) that the third Olynthiac belongs in the first prytany of 349/8.

it would be unsafe to argue from Demosthenes' demand for the appointment of nomothetes (§§ 10 f.) that the third Olynthiac belongs in the first prytany of 349/8.

page 134 note 7 How important was the possession of the Chersonese for the safety of the Athenian corn supply? Athens had managed her supply despite the hostility of Byzantium since 364 (cf. Accame, , La lega, p. 179, n. 3Google Scholar) and down to 352 the Chersonese was not entirely under her control. So it might be argued that the Chersonese was only of value to Philip if he could use his fleet which in 349/8 was still much too weak. This is in some degree true, but ports were necessary; Sestos was a regular stopping place (cf. [Dem, .] 50. 20 and Ar. Rhet. 1411a14Google Scholar, where Sestos is described as the corn-table—![]() —of the Peiraeus) and indeed from 365 it was in Adiens's possession (Nep, . Tim. i. 3Google Scholar). If Philip took Sestos and persuaded or obliged the Byzantines to act against Athenian ships at Hieros ([Dem, .] 50. 17Google Scholar, Philochorus F 162—for its site, on the Asiatic side of the Bosporus, see P.-W. iii. 752), the corn supply would have been at least seriously affected.Google Scholar

—of the Peiraeus) and indeed from 365 it was in Adiens's possession (Nep, . Tim. i. 3Google Scholar). If Philip took Sestos and persuaded or obliged the Byzantines to act against Athenian ships at Hieros ([Dem, .] 50. 17Google Scholar, Philochorus F 162—for its site, on the Asiatic side of the Bosporus, see P.-W. iii. 752), the corn supply would have been at least seriously affected.Google Scholar

page 135 note 1 Cf. i. 25.

page 135 note 2 It is sometimes asserted that Dionysius of Halicarnassus related the three Olynthiac speeches to the three expeditions, but, though he may well have done so, this is not a necessary inference from the Letter to Ammaeus X ![]()

![]() Cf. Sealey, , R.É.G. lxviii (1955), 85.Google Scholar It is a more serious question whether Philochorus did so; for in the Scholiast's introduction to the second Olynthiac (Dindorf, , viii. 74, line 10) occur the words

Cf. Sealey, , R.É.G. lxviii (1955), 85.Google Scholar It is a more serious question whether Philochorus did so; for in the Scholiast's introduction to the second Olynthiac (Dindorf, , viii. 74, line 10) occur the words ![]()

![]()

![]() Did Philochorus record speeches of Demosthenes and assign them so precisely? It would be most surprising if he did and the words

Did Philochorus record speeches of Demosthenes and assign them so precisely? It would be most surprising if he did and the words ![]() may well be added by the Scholiast. In any case this is a matter affecting the credit of Philochorus, not the importance of Demosthenes.Google Scholar

may well be added by the Scholiast. In any case this is a matter affecting the credit of Philochorus, not the importance of Demosthenes.Google Scholar

It is true that Demosthenes' defence of Philocrates on trial for proposing to negotiate with Philip came early in 348/7 (i.e. before Olynthus fell, cf. Aesch, . 2. 14Google Scholar and R.É.G. lxxiii [1960], 417, n. 2Google Scholar) and the debate that led to the dispatch of the third expedition belonged to 349/8 (cf. Philochorus, F 51Google Scholar); so it may have been the delay of this expedition that led him to despair, and we cannot be sure that he had not spoken in support of the last expedition. Yet in general it would seem that it was Eubulus and his supporters who were in power in 349 (v.i.) and it is notable that neither Aeschines (3. 54 and 58 f.) nor Demosthenes (18. 17 f.) in discussing the latter's career has anything to say about Demosthenes' political record before 346. The theory of Glotz (Res. Hist. clxx [1932]Google Scholar) that Demosthenes succeeded in establishing a war-fund, ![]() in 349/8 has been widely accepted, but it is extremely ill founded, as I hope to show elsewhere. Rather, the failure of Apollodorus ([Dem, .] 59. 5) shows that Demosthenes and his supporters were not in a position of power in 348.Google Scholar

in 349/8 has been widely accepted, but it is extremely ill founded, as I hope to show elsewhere. Rather, the failure of Apollodorus ([Dem, .] 59. 5) shows that Demosthenes and his supporters were not in a position of power in 348.Google Scholar

page 135 note 3 5.5.

page 135 note 4 3.6.

page 135 note 5 See n. 2 above.

page 136 note 1 4. 16 f.

page 136 note 2 3.6.

page 136 note 3 Accame, , op. cit., p. 178.Google Scholar

page 136 note 4 Cf. P.-W. xviii. 328.Google Scholar

page 136 note 5 Dem, . 23. 109Google Scholar, and § 2 of Libanius' Hypothesis, to Ol. 1.Google Scholar

page 136 note 6 Xen, . Hell. 5. 2. 16.Google Scholar Cf. [Dem, .] 35. 35.Google Scholar

page 136 note 7 Dem, . 9. 56.Google Scholar

page 136 note 8 Justin, . 8. 3. 10.Google Scholar

page 136 note 9 Dem, . 3. 7.Google Scholar

page 136 note 10 16. 53.

page 136 note 11 Dem, . 8. 40, 9. 66Google Scholar, and Diod, . 16. 53. 2.Google Scholar

page 137 note 1 § 5.

page 137 note 2 i.e. the attack mentioned in Dem, . 4. 17.Google Scholar

page 137 note 3 The Potidaea campaign seriously affected Athens in the Archidamian war. Even if pay was only half what it had been then, Athens could hardly afford such large sums.

page 137 note 4 The small force of ten ships proposed in 351 was to cost 92 T a year (Dem, . 4. 28Google Scholar); a larger force would have cost, perhaps, four times as much. Such expenditure would have assisted Philip in itself, for Athens could not keep it up indefinitely.

page 137 note 5 Cf. Cloché, , Étude chronologique, etc., pp. 122 f.Google Scholar

page 137 note 6 Aesch, . 2. 90.Google Scholar

page 138 note 1 How far did Demosthenes understand the change in the conditions of warfare? From 9. 47 it is clear that he was aware, at least by 341, that warfare had become professional and specialized, but his own proposals in the First Philippic and elsewhere hardly suggest that he fully appreciated die change in both tactics and strategy. In the fifth century when Macedon was weak and Athens strong, it had proved hard to guarantee the security of the Macedonian sea-board (cf. S.E.G. x. 66Google Scholar = A.T.L. D. 3Google Scholar; [Dem, .] 7. 12 is not to be taken too seriously), and in die fourth, when the balance of power had so greatly shifted, the difficulties of fighting Philip close to his base at the farthest stretch of Athens' communications were probably too great for Athens.Google Scholar

page 138 note 2 The Athenian success in stopping Philip in 352 was greater than has been generally realized. Diodorus 16. 37 records the Phocian recovery after the battle of the Crocus Field, including the assembly of a large allied force of which the 5,400 Adienians under Nausicles was barely more than half, but at the end of chapter 37 he leaves his narration of the Sacred War and returns to Philip. Chapter 38 recounts the check to Philip at Thermopylae ![]() with no mention of the Spartans, etc. The reasonable explanation is that only the Athenians got there in time. This is confirmed by Dem, . 19. 319Google Scholar where in speaking of the check to Philip Demosthenes says

with no mention of the Spartans, etc. The reasonable explanation is that only the Athenians got there in time. This is confirmed by Dem, . 19. 319Google Scholar where in speaking of the check to Philip Demosthenes says ![]()

![]()

![]() Cf. Justin, 8. 2. 8. That Athens saved Phocis so easily must have had a grave effect on the ideas of Athenian statesmen: Philip learnt his lesson.Google Scholar

Cf. Justin, 8. 2. 8. That Athens saved Phocis so easily must have had a grave effect on the ideas of Athenian statesmen: Philip learnt his lesson.Google Scholar

page 138 note 3 Dem, . 19. 9 f. and 303 f.Google Scholar Cf. R.É.G. lxxiii (1960), 418 f.Google Scholar

page 138 note 4 Aesch, . 2. 133Google Scholar, Dem, . 19. 52, 322.Google Scholar

page 138 note 5 Cf. art. cited in n. 3 above.

page 138 note 6 Plut, . Phoc. 14. 1.Google Scholar

page 138 note 7 3. 4f.

page 139 note 1 4. 35, 1. 9.

page 139 note 2 Cf. p. 138, n. 1.

page 139 note 3 Theopompus, , F.G.H. 115 F 249Google Scholar (of 353 cf. Schaefer, , op. cit. i 2. 443, n. 3Google Scholar); Polyaenus, 4. 2. 22Google Scholar, Diod, . 16. 34. 3 and 35. 5Google Scholar (all of 352); Philochorus, , F.G.H. 328 F 49Google Scholar (of 349—‘the thirty ships under Chares’, i.e. he was already provided with a force); I.G. ii 2. 207Google Scholar, line 12 (of early 348). One might guess that just as Charidemus was in 348 and probably earlier ![]() Chares was diroughout the period 353 to 348, and perhaps to 346 (cf. Aesch, . 2. 73 and 90Google Scholar but note I.G. ii 2. 1620, line 19Google Scholar), the general in command of the war for Amphipolis,

Chares was diroughout the period 353 to 348, and perhaps to 346 (cf. Aesch, . 2. 73 and 90Google Scholar but note I.G. ii 2. 1620, line 19Google Scholar), the general in command of the war for Amphipolis, ![]()

![]() (Aesch, . 2. 27Google Scholar), and that the thirty ships of 349 were the size of fleet he normally had (in Polyaenus, , loc. cit., he has only twenty ships).Google Scholar

(Aesch, . 2. 27Google Scholar), and that the thirty ships of 349 were the size of fleet he normally had (in Polyaenus, , loc. cit., he has only twenty ships).Google Scholar

page 139 note 4 Midias, who as ![]() of Plutarch of Eretria played a leading part in the dispatch of the expedition (Dem, . 21. no, 200Google Scholar), was a close associate of Eubulus (Dem, . 21. 205–7Google Scholar). Phocion appears with Eubulus in support of Aeschines in 343 (Aesch, . 2. 184Google Scholar). Hegesileos, who mysteriously

of Plutarch of Eretria played a leading part in the dispatch of the expedition (Dem, . 21. no, 200Google Scholar), was a close associate of Eubulus (Dem, . 21. 205–7Google Scholar). Phocion appears with Eubulus in support of Aeschines in 343 (Aesch, . 2. 184Google Scholar). Hegesileos, who mysteriously ![]() in Euboea (Schol, . Dem, . 19. 290Google Scholar = Dind, . p. 443l. 24Google Scholar) was a cousin of Eubulus (Dem, . 19. 290).Google Scholar

in Euboea (Schol, . Dem, . 19. 290Google Scholar = Dind, . p. 443l. 24Google Scholar) was a cousin of Eubulus (Dem, . 19. 290).Google Scholar

page 140 note 1 For Nausicles, , Diod. 16. 37. 3Google Scholar. There are several bearers of the name (cf. Pros. Att.), but there are two main candidates for the generalship of 352. First, Nausicles, son of Clearchos, who appears in the period after Chaeronea (I.G. ii 2. 1496 col. ii l. 40 f., 1628 I. 71, 1629 l. 707Google Scholar) and who is the associate of Demosthenes (Aesch, . 3. 159Google Scholar, Plut, . Dem. 21Google Scholar, Dem, . 18. 114Google Scholar, Plut, . Mor. 844 fGoogle Scholar). Secondly, the Nausicles who supported Aeschines in 343 (Aesch, . 2. 184Google Scholar), presumably the man who had proposed Aeschines for die embassy in 346 (Aesch, . 2. 18Google Scholar) and who was himself one of the ambassadors (§ 4 of 2nd Hyp, . to Dem, . 19). Since the former only appears after 338, the latter, the associate of Aeschines, called in 343 because he was an important man, is to be preferred.Google Scholar

Confirmation of Eubulus' connexion with the defence of Thermopylae is perhaps provided by Diophantus of Sphettus, who proposed the decree of thanksgiving in 352 (Dem, . 19. 86 and schol, .Google Scholar). He was an associate of Aeschines (Dem, . 19. 198Google Scholar, where Demosthenes says he will compel him to give evidence against Aeschines) and also associated with the financial administration (Aesch, . 3. 24 and 25 and schol.).Google Scholar

page 140 note 2 §§ 28–32.

page 140 note 3 Aesch, . 3. 25Google Scholar, Dinarchus, 1. 96Google Scholar, I.G. ii 2. 505, 1668.Google Scholar

page 140 note 4 See p. 138, n. 3.

page 140 note 5 As Jaeger, , op. cit., p. 108, insisted, the march of Philip to Heraeum Teichos made Demosthenes aware of the real danger. Considering that Athens was at war with Philip and that she depended so much on the safety of the corn supply, it would be surprising if Demosthenes was the only person to regard Philip seriously in 349/8.Google Scholar

- 8

- Cited by