Abstract

Little is known on the appraisal of ethically questionable not- for-profit actions such as social marketing advertising campaigns. The present study evaluates the ethical acceptance by adults of anti-obesity threat appeals targeting children, depending on the claimed effectiveness of the campaign. An experiment conducted among 176 Belgian participants by means of an online survey shows that individuals’ acceptance of social marketing practices increases along with the claimed effectiveness of the campaign. As such it demonstrates that the audience adopts a pragmatic perspective, challenging the non-consequentialist stance of social marketers who refrain themselves from using these ‘questionable’ techniques although highly effective. The trade-off between ethical judgment and claimed effectiveness varies depending on whether the threats focus on the child’s physical integrity or social life. Individual characteristics such as parenthood and age also influence the relationship. All in all, it seems that people with stronger connections to the issue such as parents are more ready to compromise. These findings enrich our insights into consequentialism in social marketing campaigns, how people respond to controversial messages targeted at vulnerable group, and open new venues to social managers and public policy makers. Managerial implications and concrete advice on how to communicate with the various audiences are proposed, as well as suggestions for future studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction and Purpose of the Study

For long, studies on unethical corporate practices in general and in marketing in particular have predominantly focussed on a business perspective, and more specifically on the company side of the commercial dyad (Leonidou et al. 2012), i.e., managers evaluating the ethicality of their own managing decisions. Later on, studies have also contributed to a better understanding of consumers’ (non-)ethical behaviours (Muncy and Vitell 1992; Steenhaut and Van Kenhove 2005). Nowadays, consumers’ attitude and behaviours toward (un)ethical brands and businesses also trigger increasingly more attention (Leonidou et al. 2012; Singh et al. 2012), focussing on the importance of companies’ ethics in consumers’ long-term purchase decisions (Leonidou et al. 2012; Singh et al. 2012), the moderating role of individual difference factors (Reiss and Mitra 1998), consumers’ demographics (Leonidou et al. 2012; Franke et al. 1997; Reiss and Mitra 1998), the ethical judgment of commercial advertising and its impact on effectiveness responses (Simpson et al. 1998; Sego 2002).

However, consumers’ ethical perception of marketing practices when no commercial objective is at stake is under-researched. Yet, a growing number of advertising campaigns have a “social marketing” focus. They pursue non-commercial goals, promoting, for instance, healthy or socially recommendable behaviours to various target groups. Due to the benevolent and altruistic intentions of social marketers, which differ from traditional marketing where campaigns also benefit the instigator, it can be expected that consumers’ perceptions of the ethicality of social marketing practices are different from that of commercial marketing.

Investigating the level of ethical acceptance of social marketing campaigns is therefore relevant from both a managerial and theoretical perspective. Social marketers might be tempted to use controversial messages that are perceived by many as ethically problematic (Hackley and Kitchen 1999; Hastings et al. 2004; Treise et al. 1994), in order to attract sufficient attention in an increasingly cluttered advertising environment (Charry and Demoulin 2012). However, messages that are perceived as controversial by the public may trigger reactance and hence be less effective. Conversely, there seems to be some agreement amongst social marketers that social objectives require more precaution than commercial issues in that the sum of ‘good’ resulting from their actions cannot justify any detrimental consequences of the campaign (Hastings et al. 2004; Henthorne et al. 1993; Donovan and Henley 2003). It is interesting to investigate to what extent this deontology, also called idealism or non-consequentialism (Burnes and By 2012) holds. If the target audiences of social marketing campaigns have a much more utilitarian (or consequentialist) perspective of ethics, in other words, if they consider that the positive consequences (the effectiveness) of a campaign may balance the negative outcomes (for instance, threatening the public), the non-consequentialist paradigm of social marketers will be challenged. Treise et al. (1994) studied controversial social marketing campaigns that stress the threatening negative consequences of behaviours to achieve compliance of the audience with message recommendations. Interestingly, the authors showed that the vast majority of adults (86.3 and 90.7 % depending on the type of message) did not object to the use of threat appeals in public service announcements, even if directed at teenagers. This suggests that the target audiences of social marketing campaigns may be relatively consequential in their judgement of the acceptability of controversial campaigns. To the same extent that “companies whose products possess inferior attributes may be more easily categorized as bad companies” (Folkes and Kamins 1999), we expect that individuals will classify as ‘good campaigns’ those whose perceived effectiveness is high. Indeed, we propose to demonstrate that, in a social marketing context, individuals focus on how effective a campaign is to infer its level of acceptability. In other words, individuals would be ready to trade off ethical acceptance for campaigns that achieve their social goal, a different perspective from what is usually expected in commercial marketing.

The first objective of our study is thus to look at the relationship between the level of perceived effectiveness of social marketing messages and the ethical acceptance of these messages in a context where, in contrast to commercial marketing, the outcomes of the campaign do not benefit the source of the campaign but its target audiences. As stated by Burnes and By (2012), this view, also known as “altruistic consequentialism”, can hardly be studied in traditional businesses as “it is difficult to see how organizations can survive for very long if leaders acted purely in an altruistic fashion” (Burnes and By 2012, p. 245). Our study therefore considers consequentialism, i.e., the maximization of good outcomes and the minimization of bad ones (Burnes and By 2012), from an original and valid perspective. In that way we fill a void in the knowledge about the response of target audiences of social marketing campaigns using altruistic consequentialist messages.

Although “vulnerable” target groups such as children (Wright et al. 2005; Nairn and Fine 2008) are considered as one of the most investigation-worthy stream of research (Schlegelmilch and Öberseder 2010; Moore 2004), studies on controversial social marketing campaigns aimed at children are scarce if not non-existent. In terms of the acceptability of such messages, taking the adults’ points of view appears necessary for various reasons. First of all, ethical concepts such as acceptability are relatively abstract. Young pre-adolescents (8-to 10-year-olds) may not have the cognitive abilities to grasp the concepts and consequences at stake (Roedder John 2008; Roedder John 1999; Bachmann Achenreiner and Roedder John 2003). Second, an adult perspective on acceptability is the most relevant one in that adults can influence their children, public policy makers and social marketers if they feel a campaign is ethically not acceptable (Hudson et al. 2008). Indeed, most people feel that parents should be in charge of what their children see on TV (Treise et al. 1994), implying that this responsibility should remain that of an adult, not a child’s decision. The second contribution of our study is that it investigates the acceptability of controversial social marketing campaigns targeted at children from an adult’s perspective, a relevant topic that, to our knowledge, has not been studied before.

Threat appeals are amongst the most often used message strategies in social marketing. Threat appeals (often also called fear appeals) are “persuasive messages designed to scare people by describing the terrible things that will happen to them if they do not what the message recommends” (Witte 1992, p. 329). These appeals usually contain two components. They present a severe threat with a high probability of occurrence, and a behavioural recommendation that can help the audience to avoid or neutralize the threat. A threat appeal is an ethically highly sensitive message strategy, especially when targeted at children (Hastings et al. 2004), that can nevertheless be very effective, also on young target groups (Charry and Demoulin 2012; Pechmann et al. 2003; Boesen-Mariani et al. 2008). Therefore it is a very relevant message format in the context of this study. Two types of threats are commonly used in social marketing campaigns, i.e., social and physical integrity threats. For instance, anti-smoking campaigns aimed at adolescents may focus on the risks smoking represents for the health or the physical abilities (physical integrity). Alternatively, they may also stress the social consequences of smoking, such as a bad breath, the latter impacting relationships with others (social threat) (Pechmann et al. 2003). In campaigns promoting healthy food habits among children (anti-obesity campaigns), either the individual’s health or social life could be the focus of threat (Charry and Pecheux 2011; Boesen-Mariani et al. 2008). The present study focuses on childhood obesity. Childhood obesity is a very “hot” topic as it is indeed considered by the World Health Organisation as one of the most challenging issue in the 21st century, overweight and obesity ranking as the fifth leading risk for death globally (W.H.O. 2010). For the first time in history, children may live shorter lives than their parents because of this (Ogden et al. 2010). Although prevention programs have been launched, their effectiveness appears limited (Doak et al. 2009; Stice et al. 2006) and the epidemic does not really lose ground (The Economist 2012). Powerful messages that are able to trigger behavioural changes are required, and threat appeals, controversial as they may be, appear an effective option (Charry and Pecheux 2011; Charry and Demoulin 2012; Boesen-Mariani et al. 2008; Chan et al. 2009). The third contribution of the study is to investigate to what extent the trade-off between acceptability of the message and its effectiveness is different for social and physical integrity threats warning against the consequences of childhood obesity. This will add to our understanding how different threat strategies aimed at children impact the acceptability of consequentialist messages among adults.

Finally, the fourth objective of the study is to investigate to what extent this trade-off mechanism is different for different audiences, with parenthood, age and gender as segmentation criteria. The literature on ethical judgements indeed shows that the latter two characteristics significantly influence individuals’ perceptions of their own and managements practices (Dalton and Ortegren 2011; Franke et al. 1997; Reiss and Mitra 1998; Roxas and Stoneback 2004; Leonidou et al. 2012). Furthermore, it is legitimate to expect that people who are parents will have a different perspective on the childhood obesity issue. It has indeed been shown that the higher the involvement in a social issue, the more positive the ethical perception of the communication made about the cause (Sego 2002). People who have children may probably be more sensitive to childhood obesity and more involved than non-parents and therefore hold different ethical and consequentialist judgments of a controversial campaign against obesity.

To investigate these issues, an experiment is set up in which two different types of threats, one related to negative social consequences and one to negative physical integrity consequences of childhood obesity, are tested in a sample of Belgian adults. Message acceptance of these two types of threat appeal as a function of perceived message effectiveness is investigated and the moderating effect of parenthood, age and gender is studied. The present study adds to our understanding of what drives controversial social marketing message acceptance as well as the role of various levels of perceived message effectiveness. Moreover, it provides social marketing practitioners with insights on how to approach various target groups that are important for campaign acceptance and support. Last, it contributes to the consequentialism debate, providing insights on its altruistic form that remains one of the least studied one (Thiroux and Krasemann 2007).

Literature Review and Hypotheses

In commercial contexts, research has demonstrated that unethical business practices may have a detrimental impact on business outcomes. Among the numerous studies stressing these findings, Leonidou et al. (2012) show that companies’ unethical decisions and actions affect the company’s image, consumers’ dissatisfaction and intentions to purchase the company’s products. Similarly a positive relationship was found between perceived ethicality of a brand and both brand trust and brand affect, the two latter constructs being positively related to brand loyalty (Singh et al. 2012). As far as unethical practices in advertising are concerned, influence of the former on advertising effectiveness has also been documented (Simpson et al. 1998). For instance, when the benefit emphasized in ads is not straightforward for customers, their intention to buy declines (Simpson et al. 1998).

It is tempting to think that campaigning for the dissemination of ideas beneficial to the society is per se ethical or will as such be accepted by the public. However, this seems rather naïve. In line with what has been found in a commercial context, it could be assumed that social marketing campaigns that are perceived as unethical are less easily accepted. Similar to what has been shown in a for-profit setting, perceived effectiveness of a campaign may influence the extent to which it is accepted. Conversely, some consumers tend to rely on the benefits they draw from practices to infer how ethical the latter are (Singhapakdi et al. 1999). Moreover, this relationship between perceived effectiveness and acceptance may be influenced by the type of controversial message, and be moderated by characteristics of those who are exposed to the campaign.

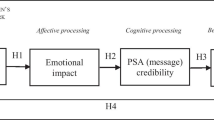

Perceived Message Effectiveness and Message Acceptance

Notwithstanding the growing ethical concern of consumers, the perception of the ethicality of business practices does not always appear to be systematically translated into consistent attitudes and behaviours toward the company and its products. Consumers’ reactions toward ethics in business indeed seem to vary according to context and personal relevance. For instance, individuals are less critical of the questionable practice when they benefit from it (Singhapakdi et al. 1999). Although comparative ads remain “bad manners” in the mind of some (Barry 1993), commercial ads embedding superiority claims over competition, i.e., containing relevant and beneficial information for the consumers, have been demonstrated more effective than non-comparative ads (Miniard et al. 2006).

In more social-oriented areas, information perceived as “useful” also contributes to the positive attitudes of consumers. In contexts such as ecology and fair-trade products, the two most emblematic examples of ethical buying behaviours (Shaw and Newholm 2002), researchers have documented the influence of positive and credible information related to the quality of the product on positive product image and buying intentions. The presence of self-claimed ecological labels on ads (a practice that is not necessarily perceived as ethical by everyone) exerted a positive influence on non-expert consumers (Benoit-Moreau et al. 2009). In fair-trade consumption contexts, information stressing the specific and differentiating attributes of products have been shown to improve individuals’ responses to this communication, increasing consumers’ intentions to purchase fair-trade ones (De Pelsmacker and Janssens 2007). Companies’ support to social issues may also enhance consumers’ perceptions of the organization if the source disclosing the information does not appear to be controlled by the company (Swaen and Vanhamme 2004). This suggests that non-commercially related sources have a positive influence on the campaigns ethical outcomes, as those informers would not be motivated by their own profits. As proposed by Koslow (2000), improved credibility of the source enhances the credibility of the message, even when overly positive, and this, in turn, provokes the necessary changes in consumers attitudes. The credibility of the organization impacts the credibility of the ad (Goldberg and Hartwick 1990), the latter influencing the outcome of advertising campaigns (MacKenzie and Lutz 1989).

Applying these findings to social marketing campaigns in which information credibility (the organization sending the message does not directly benefit from it), relevance, as well as usefulness are usually high and beneficial to consumers, these communications should lead to positive advertising evaluations. It can be expected that information presented in a social marketing campaign stressing the campaign’s effectiveness should improve acceptance. We hypothesize:

Hypothesis 1

The higher the claimed effectiveness of a message, the higher message acceptance will be.

Acceptance of Different Types of Threat Appeals

Fear or threat appeals have been used for more than 50 years and are shown to be effective in influencing behaviours. Their ability to change behaviours would be superior to that of positive appeals such as humour, action or a mere presentation of information, also on young targets (Pechmann et al. 2003; Charry and Pecheux 2011; Charry and Demoulin 2012; Boesen-Mariani et al. 2008). However, they may also cause dispensable worries among audiences, and this poses an ethical challenge (Hastings et al. 2004; Treise et al. 1994; Henthorne et al. 1993; Hackley and Kitchen 1999). In sum, just as unethical business behaviour or unethical commercial communication may be detrimental to the effectiveness of a campaign, certain social marketing and public awareness campaigns may evoke negative evaluative reactions because they are perceived as not legitimate. For instance, threat appeals, more particularly when targeted at children, may raise discomfort and lead to negative reactions. Henthorne, LaTour and Nataraajan (1993) demonstrated that threatening ads that reached a level of threat for which discomfort was perceived, producing more tension than energy, led to negative effects.

We propose that these negative perceptions vary according to the type of threat used. Threats related to the health or the physical integrity of individuals seem to predominate in messages targeting adults (see De Pelsmacker 2010; Norman et al. 2005: for reviews). However, “social threats” or threats to the social acceptance or the belonging to social groups have also received recurrent attention namely in studies on younger audiences (Pechmann et al. 2003; Schoenbachler and Whittler 1996; Charry and Pecheux 2011). Pre-adolescence is known to be a cornerstone period in individuals’ social construction. At this developmental stage, peer’s influence reaches its climax (Valkenburg and Cantor 2001) and children become very sensitive to the norms of their peer groups. It appears that socially related threats are of much more relevance to the target than the ones relative to their physical integrity (Schoenbachler and Whittler 1996; Pechmann et al. 2003; Boesen-Mariani et al. 2008; Chan et al. 2009) and this would explain their enhanced effectiveness. Nevertheless, adults appear to react more negatively to social threats addressing (pre)-adolescents than to physical integrity-related ones (Treise et al. 1994). Grown-ups are indeed well aware of the extreme importance of social acceptance at this developmental period (Schiffman et al. 2008) and they may be well aware of the risks of stigmatization. Therefore, we expect that for equal levels of perceived effectiveness, adults will favour physical integrity related threats to social ones.

Hypothesis 2

At comparable levels of claimed effectiveness, physical integrity threats are better accepted than social ones.

The Moderating Effect of Gender, Age and Parenthood on the Acceptance of Threat Appeals

Research on ethical perceptions of business practices has highlighted the relevance of segmenting individuals according to factors that may explain dissimilar responses. In this study, it is relevant to focus on gender and age. The literature on ethical perceptions indeed shows that those two dimensions may significantly influence the level of acceptance.

From a gender perspective, women are generally expected to demonstrate more sensitivity to ethical issues, showing more critical evaluation of business practices, whether they are consumers (Leonidou et al. 2012), workers for the firm (Reiss and Mitra 1998) or mere observers of those practices (for a meta-analysis, see Franke et al. 1997). According to the latter study (Franke et al. 1997), the Social Role Theory (Eagly 1997; Eagly and Carli 1982) explains these differences. Women are different from men through their “care orientation” while men focus on goal-achievement (Roxas and Stoneback 2004). Women appear to evaluate ethical practices for their ability to respect others, demonstrating empathy. Men would be more sensitive to the outcome of the action from a success/failure perspective. Therefore, it can be expected that, from a male perspective, the acceptance of a social threat will increase with its level of effectiveness. At low level of effectiveness, men’s acceptance will not be higher than that of women. Women will indeed translate their caring sense through avoidance of stimuli that may at any point be disrespectful of others or cause worry (for instance through social threats), with less focus on the potentially positive end-consequences (ad effectiveness). Consequently, their acceptance of a social threat will be low at low level of effectiveness and this acceptance will not increase to the same extent as that of men when the level of effectiveness increases. However, women’ caring sense may be satisfied when threats are effective in protecting others’ health without hurting the latter’s ego, such as in physical integrity threats. Therefore, women can be expected to accept a physical threat message to a greater extent when it is claimed to be more effective. This effect is expected to be less outspoken in men. We posit that:

Hypothesis 3a

At a low level of claimed effectiveness, there is no difference in the acceptance of social threats between men and women while men accept social threats more than women do at a high level of claimed effectiveness.

Hypothesis 3b

At a low level of claimed effectiveness, there is no difference in the acceptance of physical integrity threats between men and women, while women accept physical integrity threats more than men do at a high level of claimed effectiveness.

With respect to age, many studies have confirmed that older people demonstrate greater sensitivity to unethical practices (Muncy and Vitell 1992; Fullerton et al. 1996). This would rest on older people’s greater capacity to perceive the detrimental consequences of unethical practices (Kelley et al. 1990). They also react more strongly against unethical behaviours when they work against the norms of society (Serwinek 1992). However, Leonidou et al. (2012) did not find support for the hypothesis of different responses of age categories. They argue that consumers’ perception of ethics is not merely explained by demographics. The context would be essential to the interpretation of (un)ethical practices. Although society norms probably advocate for a fair treatment of all individuals, obesity definitely challenges the social balance, impacting social relationships and (professional) achievements of obese people through distorted self-esteem and discrimination (Brownell and Puhl 2003; Neumark-Sztainer et al. 1999; Wofford 2008; Miller and Downey 1999). Furthermore, obesity also represents an economic burden on society (Sharon 2012; Chandon and Wansink 2007; Finkelstein et al. 2010). Older people with more life experience may more accurately weigh the consequences of obesity when exposed to an anti-obesity communication campaign. Although young people probably consider the social exclusion from the obese person’s perspective, older people’s analysis probably encompasses more accurately all detrimental dimensions of obesity, adding to the impaired relationships, the healthcare costs (Finkelstein et al. 2010; Chandon and Wansink 2007), the absenteeism and the professional underachievement (Sharon 2012; Neumark-Sztainer et al. 1999). Older people should, in a teleological perspective of ethics, support more the use of social threat appeals than younger people. Extended life experience improves the understanding of the overall consequences of obesity, increases the willingness to avoid social imbalance and consequently, improves the involvement in the issue. Therefore, when social threats are considered, we expect that more involved (older) individuals will accept better the communication then less involved (younger) ones (Sego 2002). We hypothesize that

Hypothesis 4a

Regardless of the level of claimed effectiveness, older people accept social threats more than younger people do.

Based on this involvement perspective, it may be expected that as far as physical integrity threats are concerned (i.e., threats with overall higher acceptance than social ones), at low level of effectiveness, older people will find it more relevant to use physical threats than younger ones. For the latter, the level of effectiveness achieved is not sufficient to justify the use of threats. Nevertheless, as effectiveness increases, the “return on investment” appears higher for younger ones too and all groups reach the same level of acceptance. We hypothesize that

Hypothesis 4b

At low levels of claimed effectiveness, older people accept physical integrity threats more than younger people do, while there is no difference at high levels of claimed effectiveness.

Among the potential demographic variables moderating ethical acceptance, in the context of the present study, parenthood is another relevant factor to investigate. As mentioned earlier, Sego (2002) demonstrated that individuals’ involvement or support for a given social issue positively influences the perceived ethicality of an ad promoting this issue. It seems reasonable to expect that parenthood will generate a greater connectedness with childhood obesity. Child-related contexts probably appear more concrete to parents than non-parents and the negative consequences of obesity are probably more tangible, leading to more sensitivity to the issue. Therefore, when social threats are considered, we expect more positive reactions to and acceptance of threat appeals from the former (parents) than the latter (non-parents). We hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 5a

Regardless of the level of claimed effectiveness, parents accept social threats more than non-parents do.

However, as far as physical-integrity threats are concerned, although at low level of effectiveness, parents will agree more to physical threats than non-parents (the latter not seeing justification of threats in the level of effectiveness), as effectiveness increases, the “return on investment” appears higher for non-parents too and both groups reach the same level of acceptance.

Hypothesis 5b

At low levels of effectiveness, parents accept physical integrity threats more than non-parents do, while there is no difference at high levels of effectiveness.

Method

Pre-tests: Advertising Stimuli and Effectiveness Claims

Two different types of threats are being investigated and therefore require two different ads. A first pre-test was conducted to develop two threat appeals, one related to physical integrity and the other related to social threats. Both ads should warn against the dangers of childhood obesity. The first part of the pre-test consisted of in-depth interviews with 17 adults discussing 14 potential ads developed by the researchers depicting various contexts embedding physical-integrity or social threats. On the basis of the findings of this qualitative study, seven ads were retained and adapted, and a new version of each of these 7 ads was tested with 32 different adults. We asked the participants to evaluate on a 10-point scale the perceived intensity of each type of threat (either social or physical integrity), for each ad (“Could you please tell us how threatening you perceive this ad to be for the following types of threats: threats to the social life, threat to the physical integrity”). This second step of the first pre-test enabled us to select two stimuli, i.e., one physical integrity threat and one social threat that were perceived by respondents as significantly different in terms of type of threat, but equivalent in terms of their intensity. The first ad selected for our experiment (see Appendix, ad 1) scores significantly higher on social threat than on physical integrity threat (Social = 7.94 vs. PI = 4.41, t = 5.44; p < .0001). The perceived intensity of the threat of the second ad selected (see Appendix, ad 2) was high on physical integrity and significantly lower on social threat (PI = 7.06 vs. social = 5.37, t = 2.49; p = .001). We also checked whether the perceived intensity of the threat for each of the two selected ads was equivalent. Indeed, the two selected ads were judged to be equally and highly threatening (PI = 7.06; Social = 7.94, t = 1.39, p = 0.17).

The first ad (social threat) shows five teenagers (girls) on a beach, running in the water and having fun. They are wearing swimsuits. One of the five girls is clearly aside from the four others, on the left of the picture. She is obviously overweight. To emphasize the risk of social isolation of overweight people, the following text has been added: ‘Don’t fancy standing on the left-hand side of the picture? Think twice and eat fruits and vegetables! Fruits and veggies, your friends for life’. The second ad (physical integrity threat) shows an overweight male teenager sitting alone at the gym, curbing his back and staring at his feet. Three sentences were added to stress the risk on physical abilities of overweight people: ‘Too heavy? In sport, that’s not handy! Actually, how is it for you? Fruits and vegetables, that’s worth the deal!’.

A second pre-test was conducted to identify individuals’ perceptions of the effectiveness of public service announcements. As we want to assess the participants’ message acceptance as a function of the perceived effectiveness of the messages, it was important in the main study to offer effectiveness propositions that are realistic and credible. Forty-six adult individuals were asked to state how many times out of 10 a child should select a fruit instead of a chocolate bar after viewing the message for the effectiveness of the ad to be considered, first, ‘normal’ and then, ‘impressive’. These two levels should enable us to create messages with credibly increasing levels of claimed effectiveness. The average score for a ‘normal’ result was three healthy selections. ‘Impressive’ effectiveness was reached at six and a half fruit choices.

Procedure

The data for the main study were collected by means of an online survey using a 2 (type of threat: social or physical integrity) × 4 (presumed effectiveness: 4 levels) mixed design. The type of threat (social vs. physical integrity) was manipulated between subjects. The level of presumed effectiveness of the ad was treated as a within-subject factor.

The questionnaire is constructed as follows. After a brief introduction to the topic (advertising survey for obesity prevention), one of the two ads is presented. The ads are randomly assigned to the participants. With respect to the presumed level of effectiveness four scenarios are proposed to each participant. First, individuals are asked to evaluate the acceptability of the ad if, as a result of the ad, in 2 out of 10 times a piece of fruit is chosen instead of an unhealthy snack (a level of effectiveness just below the level identified as realistic in the pretest). Then, the same individuals are asked to re-evaluate their acceptability when 4 out of 10 times a piece of fruit is chosen (a level of effectiveness just above the realistic level in the pretest). The third scenario is when 6 out of 10 times a piece of fruit is chosen (a level just below an “impressive” result in the pretest). Again, respondents have to indicate their level of acceptability of the ad. Finally, respondents have to indicate their level of acceptance when 8 out of 10 times a healthy snack is chosen (a level just above an impressive one in the pretest). For the sake of parsimony, results will be reported on the lowest level of presumed effectiveness (i.e., 2 pieces of fruits out of 10 snacks) and the highest level (i.e., 8 pieces of fruits) while graphs will be presented to allow a complete perspective.

The data were collected in Belgium during spring 2012. The online survey method ensures anonymity (Malhotra 2010). Therefore, social desirability bias should be limited. The measures are described in the “Measures” section. The last questions measure age, gender and parenthood.

The sample is composed of 176 respondents. Thirty-nine per cent of our sample is less than 40 years old, 63 % has children and 57,4 % are women.

Measures

The measure of respondents’ ethical acceptance of the ad is based on Reidenbach and Robin’s scale (1990), adapted to the context of this research. It is measured by one 5-point item (“would you please indicate how “acceptable” it is, according to you, to use this ad promoting a healthy diet”) evaluating individual’s acceptance of the ad, avoiding the “ethic” term as suggested by Jones (1990). As this study used a within-subject design, the same question was to be asked multiple times to the same respondents. It seemed that limiting the number of items of the self-reported scale would increase the reliability of the responses. Mono-item measures have been indeed successfully used in previous studies to identify individuals’ ethical perception of specific advertising appeals (Treise et al. 1994). Gender and parenthood were measured on a 0/1 scale. Age was measured in two categories, i.e., 40 or younger and older than 40.

Results

We first checked that each stimulus was equally presented in each socio-demographic sub-groups (χ² age (1) = .024, p = 0.88; χ²gender (1) = 2.81, p = .094; χ²children (1) = .024, p = 0.88).

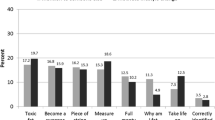

Hypothesis 1 predicts that when perceived effectiveness increases, ethical acceptance increases too. Results of the repeated-measures ANOVA shows that indeed, an increased level of effectiveness increases individuals’ acceptance of the message (F(3,525) = 62,09; p < .001). H1 is supported. Acceptance at effectiveness 2 is of 2.93 out of 5, it increases to 3.34 at level 4, 3.76 at level 6 and reaches 3.93 out of 5 at the maximum level considered (8 out of 10 healthy choices).

Hypothesis 2 proposes that physical integrity threats would be better accepted than social ones regardless of the level of effectiveness. Results confirm that the interaction between the level of effectiveness and the type of threat is not significant (F(3, 522) = 2.36, p = .07), while there is a main effect of the type of threat (F(1,174) = 5.96, p = .016). A significant difference between social and physical threat is observed at three out of four levels of claimed effectiveness (level 4: t(522) = −2.13, p = .003; level 6: t(522) = −2.62; p = .009; level 8: t(522) = −3.16, p = .002) (see Fig. 1). The difference is not significant at the lowest level of claimed effectiveness (t(522) = −1.10, p = 0.27). Physical integrity threats are better accepted than social ones. Although in the expected direction, at the lowest level of effectiveness, the social threat reaches a score of acceptance of 2.83 out of 5 which is not significantly different from the one of physical integrity (3.08). As expected in H1, there is also a main effect of the level of effectiveness (F(3,522) = 62.63, p < .0001). H2 is largely supported.

The third hypothesis predicts a moderating effect of gender. In H3a we expected that for social threats, at a low level of claimed effectiveness, no difference between men and women would be observed. This is confirmed by the results (men = 2.78, women = 2.86; t(516) = −0.28, p = 0.78). The expectation was that, at a high level of claimed effectiveness, men would accept social threats better than women. Although the results are in the expected direction (men = 3.84; women = 3.52), the difference is not significant (t(516) = 1.18, p = 0.24)) (see Fig. 2). H3a is not confirmed.

H3b predicts that at low levels of effectiveness men would not accept physical integrity threats more than women, which is confirmed (Women = 3.16; Men = 2.81; t(516) = −0.94; p = 0.35). In addition, H3b also predicts that at a high level of claimed effectiveness there would be a significant difference in favour of women, which is not significantly confirmed (Women = 4.31, Men = 4.14; t(516) = −0.65, p = 0.52). There is no significant difference in physical integrity threat acceptance between men and women, regardless of the level of effectiveness (see Fig. 3). H3b is not supported.

As far as age is concerned, H4a predicts that older people would accept social threats more than younger ones, regardless of the level of claimed effectiveness. As expected, there is no significant interaction effect between the level of effectiveness and the age group (F(3,522) = 0.71, p = 0.55). Results indicate that at all levels of effectiveness, the differences between old and young people are significant (respectively, level 2: t(516) = 4.09, p < .0001; level 4: t(516) = 4.79, p < .0001; level 6: t(516) = 4.81, p < .0001; level 8: t(516) = 4.69, p < .0001). There is a significant main effect of age (F(1,172) = 15.83, p = .0001). At the lowest level of effectiveness, older people’s score of acceptance reaches 3.25 and increases to 4.11 at the highest level of effectiveness while younger ones’ score evolves from 2.2 to 2.91 (see Fig. 4). H4a is supported.

H4b predicts that at low levels of effectiveness older people would better accept physical integrity threats than young ones, which is confirmed (old = 3.22, young = 2.74; t(516) = 1.90, p = 0.058). In addition, H4b predicts that there would be no significant difference at a high level, which is also confirmed (old = 4.29, young = 4.17; t(516) = −0.42, p = 0.67) (see Fig. 5). H4b is supported.

With respect to parenthood, we expect that the level of parents’ acceptance of social threats is higher than that of non-parents, regardless of the level of effectiveness (H5a). As expected, there is no interaction effect between claimed effectiveness and parenthood (F(3,522) = 1.45, p = 0.23). Moreover, there is a significant difference between the parent and non-parent scores for each level of claimed effectiveness: level 2: (t(516) = −3.04, p = .003), level 4: t(516) = −3.38, p = .001, level 6: t(516) = −2.82, p = .005 and high levels (t(516) = −2.82, p = .005) of claimed effectiveness. There is a main effect of parenthood (F(1,172) = 11.26, p = .001). Parents’ acceptance scores are, respectively, at the lowest and highest levels 3.13 and 3.91 while non-parents evaluations are 2.31 and 3.16 (see Fig. 6). H5a is supported.

H5b predicts that a physical integrity threat, at a low level of claimed effectiveness, would be accepted more by parents than by non-parents, while no difference would be observed at a high level of claimed effectiveness. The results confirm our expectations (lowest level: t(516) = −2.40, p = 0.02; highest level: t(516) = −0.64, p = 0.52). Parents’ score at the lowest level is equal to 3.27 while non-parents evaluate acceptance at 2.83. At the highest level, parents and non-parents score are not significantly different anymore with, respectively, 4.29 and 4.12 (see Fig. 7). H5b is supported.

Discussion and Conclusion

The present study’s objectives were fourfold. First, it intended to contribute to the consequentialist versus non-consequentialist debate in a unique and relevant context: the target group’s appraisal of marketers’ practices in social marketing by exploring the relationship between perceived effectiveness of a message and its acceptability. Second, it studied acceptance of campaigns targeting children, a vulnerable audience (Nairn and Fine 2008, Wright et al. 2005), from an adult perspective. Third, it investigated two often used but ethically questionable types of threat appeal advertising strategy to children (Hastings et al. 2004; Henthorne et al. 1993; Hackley and Kitchen 1999). Fourth, it considered socio-demographic criteria often used in studies on ethics and evaluated their impact on the ethical appraisal of threat appeals varying in perceived effectiveness.

First, we demonstrate that, in social marketing campaigns, acceptance varies according to the degree of claimed effectiveness. Although ‘questionable’ ads (threatening messages) were used, individuals seem ready to moderate their ethical judgement. As expected, in the present study, the acceptance of threat appeals increases as the level of positive outcomes presented in the campaign is enhanced. Furthermore, this seems true regardless of the type of threat. As such, our results support a consequentialist ethical perspective. This is in contrast with the idealistic stance of many social managers’ and confirms the findings of Treise et al. (1994) that the public is ready to accept ethically controversial campaigns, provided they are effective. It is also important to stress that adults tolerated highly threatening ads to a target that is considered particularly vulnerable (Nairn and Fine 2008; Wright et al. 2005).

In the context studied here, threats related to the physical integrity of children are better accepted than threats to their social interactions. This is in line with previous findings and assumptions (Treise et al. 1994). Interestingly, at the lowest level of effectiveness, there is no difference in the level of acceptance between the two types of threats. This would imply that when claimed effectiveness is low, individuals approach threat appeals with less nuances when appraising the acceptability of the campaign. Because effectiveness is low, acceptance is low whatever the content of the message. These results again support the consequentialist stance of ethics in social marketing and challenge the commonly accepted notion that social marketers in all cases need to demonstrate high standards of ethics to be acceptable.

In the context of this study, socio-demographics factors seem to influence the ethical acceptance of controversial messages varying in claimed effectiveness. The fact that certain socio-demographics are relevant moderators of the responses to social campaigns is in line with previous findings (Franke et al., 1997; Leonidou et al. 2012; Reiss and Mitra 1998). Overall, older people (40plus) show a better acceptance of threats to prevent obesity than younger ones, except when the effectiveness of threats directed at the physical integrity is high. In the latter situation, the level of acceptance is the same in the two age groups. Younger people seem to limit their acceptance of threats “when all signs are green”, that is when effectiveness is high and threats are “decent” in the eyes of the majority, which is more the case for physical integrity than for social threats. Although at first glance, these findings may come as a surprise as they suggest that younger people are actually more ‘conservative’ than their older counterparts, they confirm the all-encompassing view that individuals with extended life experience seem to be aware of the detrimental consequences of obesity. These results support Leonidou et al. (2012) when concluding that the context indeed influences the ethical acceptance of practices, and challenge research that found younger generations to be more tolerant (Fullerton et al. 1996; Muncy and Vitell 1992; Kelley et al. 1990). Parenthood (vs. non-parents) provides very similar results to that of older people (vs. younger ones). Having children, and probably the risk of seeing them obese, positively affect their acceptance of a social threat at every level of effectiveness in comparison with non-parents. However, levels of acceptance are equal when physical integrity threats produce high effectiveness. It seems reasonable that older people and parents feel somewhat more concerned by the obesity issue than their counterparts, because their respective status contributes to a better apprehension of the consequences of obesity, and as such, are ready to accept practices that may be perceived as more questionable to others. Although the correlation between being parents and being older exists, nearly 20 % of our sample is either young and parent or old and non-parent suggesting that these findings are indeed representative of the concerns of both types of individuals.

The study also investigated gender and its influence on ethical acceptance, as studied in various contexts of ethical practices (Franke et al. 1997; Leonidou et al. 2012; Reiss and Mitra 1998). Research repeatedly showed women to be less tolerant than men when evaluating potentially questionable practices. However, our findings indicate that there is no significant difference between men and women in the acceptance of threat appeals, regardless of the type of threat. It may be that although women prove to be less tolerant when the purpose of a campaign is not others-oriented, their capacity of acceptance is enhanced by the protection need of vulnerable children and that it compensates for men’s quest for performance. As Sego (2002) demonstrated when studying the impact of involvement in causes on the acceptance of ads, the more concerned you are, the more accepting you become. This would further explain our results. There is indeed no reason to expect that women are more or less concerned by childhood obesity than men, or more precisely, although reasons might be different according to gender (achieve social conformity vs. avoid performance limitation), they eventually equate.

Managerial and Public Policy Implications

The managerial and public policy implications of these findings are numerous. First, the present study stresses the importance of communicating the campaign’s presumed effectiveness to increase acceptance of the appeal. This of course advocates for conducting reliable studies to evaluate the merits of specific campaigns. Previous research has provided evidence of the superior effectiveness of social threats over other types and appeals (Boesen-Mariani et al. 2008; Schoenbachler and Whittler 1996; Pechmann et al. 2003). It thus appears justified to use social threats in social marketing campaigns although they should be combined with information on their effectiveness to optimize their acceptance. Managers and policy makers should indeed not hesitate to use challenging threats. Our study provides support to the idea that social marketers have been too timid in their approach to threats, considering that positive consequences cannot be expected to outbalance negative ones. Social marketers need not be too conservative as their targets accept the consequentialist ethical stance that positive outcomes may outweigh negative ones. Third, the insights suggest adapting the message to the target groups, especially to primary ones (i.e., the most concerned). Although this principle is fundamental to marketers, its truthfulness increases in social marketing campaign relying on threats as individuals who are not per se concerned with the issue tend to produce more negative evaluations that may potentially jeopardize the effectiveness of the campaign.

As such, it may be advisable for a prevention campaign that embeds a social threat with clear information as far as its effectiveness is concerned to consider channels that are used by both children and their parents, such as schools, children’s magazine and family websites, while steering clear from non-parents. Then, considering that growing older works in favour of acceptance, activities lead by seniors to the benefit of children (such as ‘nanny narrators’, where older women read books to children) could also be the place to disseminate messages containing social threats. Because of their extended life experience, elders indeed seem to perceive the relevance of and adhere to the use of these threats. However, mass media (T.V., billboards in street, fast food restaurants…) should be used when threats focus on the health damages of obesity. It might also be wise to use the latter type of threats when no claims of effectiveness can be provided, for instance, when no studies have been conducted on the population considered or in a rather different cultural setting.

Limitations and Further Research

First, we acknowledge that the context of our study is specific (childhood obesity) and that our findings rest on two particular stimuli. However, we believe that our extensive pre-test procedures confirm the highly threatening nature of our ads and that this allows us to state that threatening messages will be accepted if proven effective, which supports the consequentialist stance. Furthermore, the context should be perceived as reinforcing the validity of our findings, and not per se as a limiting factor. Children are indeed generally considered a vulnerable target (Nairn and Fine 2008, Wright et al. 2005) and consequently, it is accepted that higher levels of ethics are called for to address them. Our results indicate that in this setting, highly intense threats were nonetheless accepted by adults, offering support to intense threats if effective in many much less ethical issues.

Then, considering the crucial role of the effectiveness claim in the acceptance of the message, it seems relevant to further explore the optimal ways to present this information. Follow up studies should enable social marketers to consider appropriate creative strategies that ensure processing of effectiveness claims.

Investigating other variables such as the media or communication channel used, the degree of involvement with the issue and how high the topic is on the political agenda (in other words, how important the issue is debated among policy makers) seem relevant as a better understanding of the process of message acceptance may offer interesting insights. As stressed earlier, ethical acceptance seems very much related to the context (Leonidou et al., 2012) and it appears important to untangle what factors can be considered relative to the context and which variables are ex-situ. The role played by perceived acceptability on effectiveness also seems important to evaluate as this would complete the appraisal of the whole effectiveness process. The latter indeed eventually loops, the effectiveness of the campaign impacting the effectiveness that can be claimed. In all instances, effectiveness of a message cannot just be claimed ‘like that’. There should be credible sources or insights to substantiate the information provided on the effectiveness. As such, the role of the credibility of the source represents another area for further study. Credibility, and its components trustworthiness and expertise (Hovland and Weiss 1951) could indeed reinforce the strength of effectiveness claims and increase acceptance. It would also be interesting to compare different stakeholders’ perspective. Our focus was set on adults, somewhat ignoring the ‘expertise’ professionals may have on the issue. For instance, what would be health professionals’ responses to those messages? Would people involved in the creative process react differently? How may the managerial dimension in these two targets influence their perceptions and to what extent would those perceptions be different from that of laymen? People may be ‘concerned’ about the issue at various levels and this requires further investigation.

The current study also focussed on primary socio-demographic variables such as gender and age. Values and other cultural influences seem to represent other important dimensions to study in ethical acceptance (Hunt and Vitell 2006). It may indeed be expected that individual will perceive and respond to messages differently according to the characteristics of the societies they belong to (de Mooij and Hofstede 2010; Forsyth et al. 2008). Even within the same society, cultural differences may exist in the acceptance of threatening messages and this raises issues since campaigns may be largely broadcasted. People may then differ on an individual basis due to the values they favour, their personality, their personal experience with the issue (obesity history in the family), and so on. More cultural and personal variables need to be considered to provide a better understanding of the mechanisms at play.

References

Bachmann Achenreiner, G., & Roedder John, D. (2003). The meaning of brand names to children: A developmental investigation. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 13(3), 205–219.

Barry, T. E. (1993). Comparative advertising: What have we learned in two decades? Journal of Advertising Research, 33(2), 19–29.

Benoit-Moreau, F., Larceneux, F., & Parguel, B. (2009). Le greenwashing publiciataire est-il efficace? Une analyse de l’élaboration négative des éléments d’exécution. Paper presented at 25ième Congrès de l’ Association Française du Marketing (AFM). pp. 14–15 mai.

Boesen-Mariani, S., Werle, C., Gavard-Perret, M.-L., & Vellera, C. (2008). Preventing youth obesity: Effective means of promotion. Paper presented at Latin American Advances in Consumer Research.

Brownell, K. D., & Puhl, R. M. (2003). Stigma and discrimination in weight management and obesity. The Permanent Journal, 7(3), 21–23.

Burnes, B., & By, R. (2012). Leadership and change: The case for greater ethical clarity. Journal of Business Ethics, 108(2), 239–252.

Chan, K., Prendergast, G., Gronhoj, A., & Bech-Larsen, T. (2009). Communicating healthy eating to adolescent. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 24(4), 214–228.

Chandon, P., & Wansink, B. (2007). The biasing health halos of fast-food restaurant health claims: Lower calorie estimates and higher side-dish consumption intentions. Journal of Consumer Research, 34(3), 301–314.

Charry, K. M., & Demoulin, N. T. M. (2012). Behavioural evidence of the effectiveness of threat appeals in the promotion of healthy food to children. International Journal of Advertising, 31(4), 741–771.

Charry, K., & Pecheux, C. (2011). Enfants et promotion de l’alimentation saine: étude de l’efficacité de l’utilisation de menaces en publicité. Recherche et Applications en Marketing, 26(2), 2–28.

Dalton, D., & Ortegren, M. (2011). Gender differences in ethics research: The importance of controlling for the social desirability response bias. Journal of Business Ethics, 103(1), 73–93.

de Mooij, M., & Hofstede, G. (2010). The Hofstede model. International Journal of Advertising, 29(1), 85–110.

De Pelsmacker, P. (2010). Wie is bang van fear appeal. Angstprikkels in sociale marketing. Amsterdam: Stichting Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek Commerciële Communicatie, SWOCC.

De Pelsmacker, P., & Janssens, W. (2007). A model for fair trade buying behaviour: The role of perceived quantity and quality of information and of product-specific attitudes. Journal of Business Ethics, 75(4), 361–380.

Doak, C., Heitmann, B. L., Summerbell, C., & Lissner, L. (2009). Prevention of childhood obesity—What type of evidence should we consider relevant? Obesity Reviews, 10, 350–356.

Donovan, R., & Henley, N. (2003). Social marketing, principles and practice. Melbourne: IP Communications.

Eagly, A. H. (1997). Sex differences in social behavior: Comparing social role theory and evolutionary psychology. American Psychologist, 50, 1380–1383.

Eagly, A. H., & Carli, L. L. (1982). Sex of researchers and sex-typed communications as determinants of sex differences in influenceability: A meta-analysis of social influence studies. Psychological Bulletin, 90, 1–20.

Finkelstein, E. A., Strombotne, K. L., & Popkin, B. M. (2010). The costs of obesity and implications for policymakers. Choices, 25(3).

Folkes, V. S., & Kamins, M. A. (1999). Effects of information about firms’ ethical and unethical actions on consumers’ attitudes. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 8(3), 243–259.

Forsyth, D. R., O’Boyle, E. H., & McDaniel, M. A. (2008). East meets west: A meta-analytic investigation of cultural variations in idealism and relativism. Journal of Business Ethics, 83, 813–833.

Franke, G. R., Crown, D. F., & Spake, D. F. (1997). Gender differences in ethical perceptions of business practices: A social role theory perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology, 82(6), 920–934.

Fullerton, S., Kerch, K. B., & Dodge, H. R. (1996). Consumer ethics: An assessment of individual behavior in the market place. Journal of Business Ethics, 15(7), 805–814.

Goldberg, M. E., & Hartwick, J. (1990). The effects of advertiser reputation and extremity of advertising claim on advertising effectiveness. Journal of Consumer Research, 17(2), 172–179.

Hackley, C. E., & Kitchen, P. J. (1999). Ethical perspectives on the postmodern communications Leviathan. Journal of Business Ethics, 20(1), 15–26.

Hastings, G., Stead, M., & Webb, J. (2004). Fear appeals in social marketing: Strategic and ethical reasons for concern. Psychology and Marketing, 21(11), 961–986.

Henthorne, T. L., LaTour, M. S., & Nataraajan, R. (1993). Fear appeals in print advertising: An analysis of arousal and ad response. Journal of Advertising, 22(2), 59.

Hovland, C. I., & Weiss, W. (1951). The influence of source credibility on communication effectiveness. Public Opinion Quaterly, Winter, 635–650.

Hudson, S., Hudson, D., & Peloza, J. (2008). Meet the parents: A parent’s perspective on product placement in children’s films. Journal of Business Ethics, 80, 289–304.

Hunt, S. D., & Vitell, S. J. (2006). The general theory of marketing ethics: A revision and three questions. Journal of Macromarketing, 26(2), 143–153.

Jones, W. A. (1990). Students views of “Ethical” issues: A situation analysis. Journal of Business Ethics, 9, 201–205.

Kelley, S. W., Ferrell, O. C., & Skinner, S. J. (1990). Ethical behavior among marketing researchers: An assessment of selected demographic characteristics. Journal of Business Ethics, 9(8), 681–688.

Koslow, S. (2000). Can the truth hurt? How honest and persuasive advertising can unintentially lead to increased consumer skepticism. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 34(2), 245.

Leonidou, L. C., Kvasova, O., Leonidou, C. N., & Chari, S. (2012). Business unethicality as an impediment to consumer trust: The moderating role of demographic and cultural characteristics. Journal of Business Ethics, 112(3), 1–19.

MacKenzie, S. B., & Lutz, R. J. (1989). An empirical examination of the structural antecedents of attitude toward the ad in an advertising pretesting context. Journal of Marketing, 53(2), 48–65.

Malhotra, N. K. (2010). Marketing Research, an applied orientation. (6th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Miller, C. T., & Downey, K. T. (1999). A meta-analysis of heavyweight and self-esteem. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 3(1), 68–84.

Miniard, P. W., Barone, M. J., Rose, R. L., & Manning, K. C. (2006). A further assessment of indirect comparative advertising claims of superiority over all competitors. Journal of Advertising, 35(4), 53–64.

Moore, E. S. (2004). Children and the changing world of advertising. Journal of Business Ethics, 52(2), 161–167.

Muncy, J. A., & Vitell, S. J. (1992). Consumer ethics: An investigation of the ethical beliefs of the final consumer. Journal of Business Research, 24(4), 297–311.

Nairn, A. C., & Fine, C. (2008). Who’s messing up with my mind? The implication of dual-process models for the ethics of advertising to children. International Journal of Advertising, 27(3), 447–470.

Neumark-Sztainer, D., Story, M., & Harris, T. (1999). Beliefs and attitudes about obesity among teachers and school health care providers working with adolescents. Journal of Nutrition Education, 3(1), 3–9.

Norman, P., Boer, H., & Seydel, E. R. (2005). Protection motivation theory. In M. Conner & P. Norman (Eds.), Predicting health behaviour (pp. 81–126). Maidenhead: Open University Press.

Ogden, C. L., Carroll, M. D., Curtin, L. R., Lamn, M. M., & Flegal, K. M. (2010). Prevalence of high body mass index in US children and adolescents, 2007–2008. Journal of the American Medical Association, 303(3), 242–249.

Pechmann, C., Zhao, G., Goldberg, M. E., & Reibling, E. T. (2003). What to convey in antismoking advertisements for adolescents: The use of protection motivation theory to identify effective message themes. Journal of Marketing, 67(April), 1–18.

Reidenbach, R. E., & Robin, D. P. (1990). Toward the development of a multidimensional scale for improving evaluations of business ethics. Journal of Business Ethics, 9(8), 639–653.

Reiss, M. C., & Mitra, K. (1998). The effects of individual difference factors on the acceptability of ethical and unethical workplace behaviors. Journal of Business Ethics, 17(14), 1581–1593.

Roedder John, D. L. (1999). Consumer socialization of children: A retrospective look at twenty-five years of research. Journal of Consumer Research, 26(3), 183–213.

Roedder John, D. L. (2008). Stages of consumer socialization. The development of consumer knowledge, skills, and values from childhood to adolescence. In C. P. Haugtvedt, P. M. Herr, & F. R. Kardes (Eds.), Handbook of consumer psychology (pp. 221–246) New York: Taylor and Francis Group, LLC.

Roxas, M. L., & Stoneback, J. Y. (2004). The importance of gender across cultures in ethical decision-making. Journal of Business Ethics, 50(2), 149–165.

Schiffman, L. G., Lazar Kanuk, L., & Hansen, H. (2008). Consumer behavior, a European outlook. Harlow: Pearson Education Limited.

Schlegelmilch, B., & Öberseder, M. (2010). Half a century of marketing ethics: Shifting perspectives and emerging trends. Journal of Business Ethics, 93(1), 1–19.

Schoenbachler, D. D., & Whittler, T. E. (1996). Adolescent processing of social and physical threat communications. Journal of Advertising, 25(4), 37–54.

Sego, T. (2002). Consumers’ ethical judgments of issue advertising. Advances in Consumer Research, 29, 80–85.

Serwinek, P. J. (1992). Demographic and related differences in ethical views among small businesses. Journal of Business Ethics, 11(7), 555–566.

Sharon, B. (2012). Costs of obesity. Hufftington Post.

Shaw, D., & Newholm, T. (2002). Voluntary simplicity and the ethics of consumption. Psychology and Marketing, 19(2), 167–185.

Simpson, P. M., Brown, G., & Widing, R. E, I. I. (1998). The association of ethical judgment of advertising and selected advertising effectiveness response variables. Journal of Business Ethics, 17(2), 125–136.

Singh, J. J., Iglesias, O., & Batista-Foguet, J. M. (2012). Does having an ethical brand matter? The influence of consumer perceived ethicality on trust, affect and loyalty. Journal of Business Ethics, 111(4), 541–549.

Singhapakdi, A., Vitell, S. J., Rao, C. P., & Kurtz, D. L. (1999). Ethics gap: Comparing marketers with consumers on important determinants of ethical decision-making. Journal of Business Ethics, 21(4), 317–328.

Steenhaut, S., & Van Kenhove, P. (2005). Relationship commitment and ethical consumer behavior in a retail setting: The case of receiving too much change at the checkout. Journal of Business Ethics, 56(4), 335–353.

Stice, E., Shaw, H., & Marti, N. C. (2006). A meta-analytic review of obesity prevention programs for children and adolescents: The skinny on interventions that work. Psychological Bulletin, 132(5), 667–691.

Swaen, V., & Vanhamme, J. (2004). The use of corporate social responsibility arguments in communication campaigns: Does source credibility matter? Paper presented at advances in consumer research.

The Economist (2012). Special report on obesity. The Economist.

Thiroux, J. P., & Krasemann, K. W. (2007). Ethics: Theory and practice. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson, Prentice Hill.

Treise, D., Weigold, M. F., Conna, J., & Garrison, H. (1994). Ethics in advertising: Ideological correlates of consumer perceptions. Journal of Advertising, 23(3), 59–69.

Valkenburg, P. M., & Cantor, J. (2001). The development of a child into a consumer. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 22(1), 61–72.

W.H.O. (2010). Set of recommendations on the marketing of foods and non-alcoholic beverages to children. In W. Press (Ed.). Geneva: World Health Organization.

Witte, K. (1992). Putting the fear back into fear appeals: The extended parallel process model. Communication Monographs, 59, 329–349.

Wofford, L. G. (2008). Systematic review of childhood obesity prevention. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 23(1), 5–19.

Wright, P., Friestad, M., & Boush, D. M. (2005). The development of marketplace persuasion knowledge in children, adolescents, and young adults. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 24(2), 222–233.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Ads 1a (French) &1b (Dutch): Social threats

Ads 2a (French) & 2b (Dutch) : Physical integrity

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Charry, K., De Pelsmacker, P. & Pecheux, C.L. How Does Perceived Effectiveness Affect Adults’ Ethical Acceptance of Anti-obesity Threat Appeals to Children? When the Going Gets Tough, the Audience Gets Going. J Bus Ethics 124, 243–257 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1856-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1856-2