Abstract

Despite increased calls for hospital ethics committees to serve as default decision-makers about life-sustaining treatment (LST) for unrepresented patients who lack decision-making capacity or a surrogate decision-maker and whose wishes regarding medical care are not known, little is known about how committees currently function in these cases. This was a retrospective cohort study of all ethics committee consultations involving decision-making about LST for unrepresented patients at a large academic hospital from 2007 to 2013. There were 310 ethics committee consultations, twenty-five (8.1 per cent) of which involved unrepresented patients. In thirteen (52.0 per cent) cases, the ethics consultants evaluated a possible substitute decision-maker identified by social workers and/or case managers. In the remaining cases, the ethics consultants worked with the medical team to contact previous healthcare professionals to provide substituted judgement, found prior advance care planning documents, or identified the patient’s best interest as the decision-making standard. In the majority of cases, the final decision was to limit or withdraw LST (72 per cent) or to change code status to Do Not Resuscitate/Do Not Intubate (12 per cent). Substitute decision-makers who had been evaluated through the ethics consultation process and who made the final decision alone were more likely to continue LST than cases in which physicians made the final decision (50 per cent vs 6.3 per cent, p = 0.04). In our centre, the primary role of ethics consultants in decision-making for unrepresented patients is to identify appropriate decision-making standards. In the absence of other data suggesting that ethics committees, as currently constituted, are ready to serve as substitute decision-makers for unrepresented patients, caution is necessary before designating these committees as default decision-makers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Clinicians use the term “unrepresented” or “unbefriended” to refer to patients who lack decision-making capacity, have no clear documentation of preferences for medical interventions, and lack a surrogate decision-maker or any readily identifiable candidate for that role (Pope and Sellers 2011). Unrepresented patients typically come from one of three populations: the mentally ill or developmentally disabled/delayed, the cognitively impaired elderly, or the socially isolated who have had a sudden or progressive impairment in decision-making capacity (Karp and Wood 2003). Although there is general agreement in clinical ethics that a substituted judgement or a best-interest standard should guide medical decision-making for unrepresented patients, there is substantial variation in legal, institutional, and de facto practices in this regard.

The recommended procedure for medical decision-making for an unrepresented patient depends on the specific state in which the hospital is located, including whether the hospital cares for military veterans; why the patient is unrepresented, with different default decision-maker designees for the mentally ill and developmentally delayed compared to the socially isolated or elderly; institutional policies, including whether third parties such as social workers or chaplains must be involved; and the type of decision, with state laws requiring different authority to consent to a routine procedure, to refuse cardiopulmonary resuscitation, and to withdraw medical nutrition or hydration (Varma and Wendler 2007; Veteran’s Administration 2014; Karp and Wood 2003). The most common expectation is that the treating medical team initiate legal proceedings for a court-appointed guardian if they can identify no other potential surrogate (Pope and Sellers 2011). The guardianship process, however, can move slowly, and public guardians are often overworked or simply unavailable (Pope 2013).

In practice, many of these decisions for an unrepresented patient, particularly around initiating, continuing, or stopping life-sustaining treatment (LST) default to the patient’s treating physician, especially in the intensive care unit (ICU). For example, White et al. found that in a large academic hospital medical ICU only 11 per cent of decisions to limit or withhold LST for an unrepresented patient were made in consultation with an ethics committee or court (White et al. 2006). They did not report whether these decisions were made because of poor prognosis in a time limited situation in which further review was not feasible or whether this was standard practice in their centre. In a related multicentre study, however, only 19 per cent of decisions about LST were made with institutional or judicial review (White et al. 2007). Despite this common default, recent commentators have argued that it is inappropriate for physicians to serve as surrogate decision-makers for the unrepresented (White, Jonsen, and Lo 2012; Pope 2013). Acknowledging the inefficiency of having courts formally designate guardians in every case, these authors have argued that multidisciplinary ethics committees—ideally unaffiliated with the treating institution—serve as surrogate decision-makers for the unrepresented (White, Jonsen, and Lo 2012; Pope 2013).

The theoretical advantages of utilizing multidisciplinary ethics committees include ensuring due process, minimizing conflicts of interest, and limiting potential biases related to disability, race, or culture, all of which may be concerns when individual physicians act as decision-makers. There are, however, no data on whether ethics committees, as currently constituted, are prepared for this responsibility, particularly given lack of consensus on membership standards and appropriate training (Pope 2014; Rubin and Courtwright 2013). Nor do we know what role, if any, these committees are now playing, including whether they are limited to gathering additional information about patient values, searching for surrogates, or whether they are already making treatment recommendations and, if so, what those recommendations are. Such data are necessary to assess the feasibility and implementation barriers to using ethics committees as surrogate decision-makers for the unrepresented.

The ethics committee at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), known as the Edwin H. Cassem Optimum Care Committee, can be consulted for patients who lack decision-making capacity, whose values and wishes regarding medical care are not known, and for whom no clear surrogate decision-maker can be found. When these patients are admitted with life-threatening conditions with an accompanying poor prognosis and a general consensus among the treating clinicians that LST poses significant burdens without clear benefit, particularly those for whom death is imminent regardless of what treatment is provided, MGH policy does not require petition for appointment of a legal guardian for not offering or not continuing LST (Fig. 1). The ethics committee, however, may be consulted to help reflect on decision-making for these patients and for unrepresented patients with life-threatening illness who are not imminently dying. The committee itself is a multidisciplinary organization with representation from nursing, subspecialty and generalist physicians, social work, clinical ethics, respiratory therapy, case management, and community members, among others (Courtwright et al. 2013). Hospital administration, risk management, and the Office of General Counsel are not directly represented on the ethics committee in order to avoid concerns about conflict of interest, although the committee may seek advice in particular cases from individuals in these departments.

A senior member of the ethics committee with training according to American Society for Bioethics and Humanities guidelines typically performs individual consultations in conjunction with one or more junior members of the committee (Tarzian et al. 2013). The full committee is available to discuss more complex cases prospectively, if there is sufficient time, and the full committee retrospectively reviews all cases, which serves as a peer review, hospital policy review, and quality improvement mechanism. Using the consultation records of the MGH ethics committee, we investigated all ethics consultations requested for decision-making for unrepresented patients. We hypothesized that the ethics consultants primarily played an advisory role in these cases and did not make specific treatment recommendations.

Methods

Consultation Database

We reviewed all ethics committee consultations from 2007 to 2013 and included those involving decision-making for unrepresented patients. We obtained socio-demographic and clinical data from ethics committee consultation and medical records as described previously (Courtwright et al. 2015). To provide context for the ethics consultation cases, we also collected age, race/ethnicity, primary language, and insurance status on all adult admissions between January 1, 2007, and December 31, 2013, using the MGH Research Patient Data Registry (RPDR) (Nalichowski et al. 2006).

We reviewed consultation notes and medical records of the included patients to identify the central themes of ethics committee involvement in consultations for unrepresented patients. This included the role of the ethics consultants, who made the final decision, and the content of that decision, specifically whether to continue or limit LST.

We defined the final decision-maker as the person or persons whose treatment decision was documented in the medical record and subsequently carried out. For example, if the ethics consultants wrote that the final decision should be based on the patient’s best interests but did not make a specific treatment recommendation and the attending physician wrote that the appropriate course of action was to withdraw mechanical ventilation, then the attending physician made the final decision. If the ethics consultants made a specific treatment recommendation without additional documentation from the attending physician, then the ethics consultants made the final decision.

If the ethics consultants documented that, based on conversations with past healthcare providers, the patient would not want tracheotomy and the attending physician documented agreement with that assessment and withdrew mechanical ventilation, then the ethics consultants and the attending physician would be the final decision-makers. If the ethics consultants identified a family member as a substitute decision-maker and that person made the final decision without additional documentation from the ethics consultants or physician, then the substitute decision-maker alone was considered the final decision-maker.

When the ethics consultants commented on the appropriateness of a potential surrogate decision-maker or identified a specific decision-making standard but did not document a specific treatment recommendation to limit or continue LST, they were considered advisory. If they made a specific treatment recommendation to limit or to continue LST, they were considered to be decision-makers. In all cases, the primary medical team wrote the actual orders to withdraw or continue LST.

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented descriptively. For the purposes of comparison with the general inpatient population, age (>65 vs ≤65), race/ethnicity (white vs non-white [including Hispanic]), primary language (English vs non-English primary language), and insurance status (insured vs underinsured) were treated as categorical variables and compared using chi-square tests as previously described (Courtwright et al. 2015). We performed a Fisher exact test to evaluate whether physicians withdraw LST more frequently than individuals who were identified through the ethics consultation process as the substitute decision-maker. Study data were collected and managed using Research Electronic Data Capture, an electronic data capture tool hosted at MGH. All analyses were performed using Stata (Version 14, Stata Corp, College Station, Texas). The Institutional Review Board at MGH approved the study.

Results

Between January 1, 2007, and December 31, 2013, there were 243,197 adult inpatient admissions and 310 ethics committee consultations. Among these cases, twenty-five (8.1 per cent) involved unrepresented patients.

Descriptive Analysis

The socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of patients in the cohort are presented in Table 1. They were primarily white men who were born in the United States and were living independently in the community prior to admission. A minority were transgender (8.0 per cent), non-white (20 per cent), had a non-English primary language (8 per cent), or were born outside of the United States (4.5 per cent). Twenty percent of patients were admitted from a skilled-nursing or assisted-living facility and 16 per cent were homeless. As expected, none of the patients were believed to have full decision-making capacity to limit or continue LST and a majority (56 per cent) were not alert at the time of the consult request. Most of the patients (76 per cent) were in an ICU on multiple life-sustaining treatments and most (84 per cent) were full code. In five (20 per cent) cases the patient had a healthcare proxy or designated surrogate decision-maker, but that person refused to be involved, making the patient de facto unrepresented.

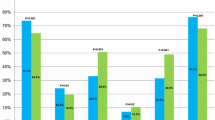

Comparing the general inpatient population to unrepresented patients in the cohort, there was no difference in race (18.5 per cent non-white vs 20 per cent, p = 0.85), age (39.4 per cent over age 65 vs 44 per cent, p = 0.64), or primary language (8.9 per cent with non-English primary language vs 8 per cent, p = 0.87). Compared to the general inpatient population, a greater percentage of unrepresented patients were underinsured (15.6 per cent vs 64 per cent, p < 0.001).

The characteristics of the consultation requests and the decision-making process are presented in Table 2. In thirteen (52 per cent) cases, the ethics consultants evaluated a possible substitute decision-maker identified by social work and case management. In three (12 per cent) cases, in conjunction with social work and the primary medical team, ethics consultants contacted the patient’s previous providers who gave input on prior healthcare decisions as a form of substitute judgement. In two (8 per cent) cases, ethics consultants identified ACP documents that could provide subjective judgement about limiting LST. In four (16 per cent) cases, they identified the patient’s best interests as the appropriate decision-making standard since there was not a possible substitute decision-maker or information about past treatment preferences. In two (8 per cent) cases, the ethics consultants made a specific treatment recommendation, one to withdraw treatment and one to perform a life-sustaining intervention. Both of these consultants were physicians. In one (4 per cent) case, the ethics consultants recommended that psychiatry reassess the patient’s capacity to make decisions about code status.

When the ethics consultants were asked to evaluate a possible substitute decision-maker, this person was often an estranged or distant sibling (23.1 per cent) or an adult child (15.4 per cent). In six (46.1 per cent) cases, however, the ethics consultants believed a close friend or neighbour could serve as a substitute decision-maker. In the majority of cases (53.8 per cent) in which a possible substitute decision-maker was evaluated, however, either physicians or the ethics consultants were also involved in the final decision about LST. This was particularly true when the possible substitute decision-maker was a friend rather than a family member. In almost all of these cases, the attending physicians recommended a course of action to which the possible substitute decision-maker provided assent, rather than deciding independently. In only one (16.7 per cent) case did a patient’s friend make the final decision alone, and that person had discovered documents that identified him as the healthcare proxy. In contrast, in the majority of cases (71.4 per cent) in which the possible substitute decision-maker was a family member, that person made the final treatment decision alone.

In the twelve cases in which there was not a possible substitute decision-maker, the treating physician made the final treatment decision alone in four (33.3 per cent) cases and in conjunction with the ethics consultants in five (41.7 per cent) cases. The EC used ACP documents to inform a decision in two (16.7 per cent) cases and, in the case in which the ethics consultants asked psychiatry to re-evaluate the patient’s decision-making capacity, he made the final decision himself. In the majority of cases, the final decision was to limit or withdraw LST (72 per cent) or to change code status to Do Not Resuscitate/Do Not Intubate (12 per cent). This decision was made most often on the grounds that death was imminent no matter what treatment was provided or that the burdens of ongoing treatment substantially outweighed any foreseeable benefits. The MGH policy on LST among unrepresented patients was rarely directly cited in the medical record. Substitute decision-makers who made the final decision alone were significantly more likely to continue LST than cases in which physicians and/or the ethics consultants were involved in the final decision (50 per cent vs 6.3 per cent , p = 0.04). In-hospital mortality was 64 per cent in the cohort, and the majority of patients who survived their hospitalization were discharged to hospice.

Discussion

There has been an ongoing normative and policy discussion about who should decide for unrepresented patients, particularly regarding whether to continue or to limit life-sustaining treatment (Rubin and Courtwright 2015; White et al. 2012; Pope 2013). Several recent articles have suggested that ethics committees are better situated to play this role than attending physicians, a common default. Here we report on the actual experience of an ethics committee that may be consulted to reflect on decision-making for unrepresented patients. Our primary findings were that many of the patients that were identified as unrepresented had possible substitute decision-makers and that the role of ethics consultants was most often to evaluate the appropriateness of having these individuals serve as surrogates. More generally, the primary role of the ethics consultants was to identify which of the three broadly recognized forms of substitute decision-making—subjective judgement, substituted judgement, or best interests—was the appropriate decision-making standard in a given case.

The number of unrepresented patients in our case series was significantly lower than previous reports. For example, White et al. found that forty-nine or 16 per cent of patients admitted to a large academic ICU over a seven-month period were unrepresented and required decision-making about continuing, initiating, or stopping a life-sustaining treatment (White et al. 2006). In contrast, we identified only twenty-five unrepresented patients out of several hundred thousand inpatient admissions over a seven-year period. While this could reflect differences in patient populations, advance care planning, or the efforts of inpatient teams to identify surrogates, it is most likely that the ethics committee is not always consulted in these cases. We suspect that most clinicians pursue guardianship for unrepresented patients, although this is an anecdotal observation based on our clinical experiences in our institution. We do not definitely know how and by whom decisions were made for patients when the ethics committee was not involved, including whether the courts or the Office of General Counsel were consulted.

The demographics of unrepresented patients in our cohort were, however, similar to previous studies. For example, White et al. (2006) found that 27 per cent of unrepresented patients were non-white compared to 20 per cent in our cohort and that, similar to our data, a majority were middle-aged men. Previous studies have not reported on the prevalence of transgender individuals among the unrepresented, although their overrepresentation compared to other ethics consultation cases is not surprising given the rates of family estrangement in this group (Williams and Freeman 2007). Also unsurprisingly, a number of patients in our cohort were homeless or living in a nursing home, populations that have been identified as higher risk for being unrepresented (Karp and Wood 2003). Two of the five patients admitted from a nursing home, however, had ACP documents regarding LST that were, somewhat atypically in our clinical experience, not found until ethics committee involvement, emphasizing the importance of systems to ensure transfer of these documents between institutions (Schmidt et al. 2013). In this respect, the wider use of medical or physician orders for life-sustaining treatment (M/POLST) forms, which are physician orders regarding LST that apply outside of the hospital setting, may reduce these scenarios. MOLST and POLST forms, however, are only of use for patients with decision-making capacity or patients with surrogates, and so it is unclear to what extent they would alleviate decision-making dilemmas for unrepresented patients.

There were very few patients in our cohort who had not had longitudinal contact with the healthcare system such as clinical teams embedded in homeless shelters, primary care providers, previous inpatient hospitalizations, or medical staff at nursing facilities. While these individuals and groups sometimes proved helpful in identifying a pattern of health-related behaviours to inform substituted judgement, this finding emphasizes missed opportunities to allow the patients in our cohort to document their own wishes in ACP documents (Happ et al. 2002; Ahluwalia et al. 2012). Importantly, however, in 20 per cent of cases, the patient had previously designated a healthcare proxy, but that person refused to be involved in the decision-making process. This suggests that, as with patients with surrogates, better advance care planning will not mitigate all questions about decision-making among the unrepresented.

In the majority of cases, the role of the ethics consultants was to evaluate and to advise possible substitute decision makers—thus mitigating the need to pursue formally the MGH LST treatment policy—and to identify appropriate decision-making standards. In doing so, consultants invoked all three of the commonly recognized forms of surrogate decision-making, including subjective judgement, substitute judgement, and best interests (Brock 1995). Perhaps unsurprisingly, when the possible substitute decision-maker was a more distant relation or unrelated individual, such as a close friend, the ethics consultants and attending physicians were more heavily involved in the decision-making process. These individuals often helped provide a portrait of the patient’s life outside of the hospital, allowing a kind of synthetic substitute judgement rather than fully taking on the surrogate decision-maker role (King 1996). In one of the two cases in which the ethics consultants explicitly made treatment recommendations, the primary team declined to follow the recommendation given a change in the patient’s clinical status following the consultation. In the other case, the primary team accepted the recommendation, which was made by an ethics consultant who was also a physician with significant experience in treating patients with the condition under consideration. In no case, however, were ethics consultants the sole decision-maker, and advice was largely given based on the medical prognosis established by physicians involved in the case. There was always an attending physician note either documenting agreement with the ethics consultants’ recommendation or documenting that the identified substitute decision-maker agreed with the ethics consultants’ recommendation.

Finally, the observation that substitute decision makers who made the final decision alone were significantly more likely to continue LST than physicians or the ethics consultants requires further exploration. We were unable to assess whether there were differences in the underlying illness severity or patient prognosis, although attending physician decision-making was always accompanied by documentation that death was imminent or that the burdens of treatment grossly outweighed the benefits and were not in the patient’s best interest. It may be that the substitute decision makers in these cases, most often distant or estranged relatives, were not fully comfortable with limiting LST. Alternatively, it may be that differences in how patients/surrogates and physicians/ethics consultants make quality of life judgements led the latter group to pursue limitation of life-sustaining treatment more commonly (O’Donnell et al. 2003; Solomon et al. 1993). This would be consistent with the broader literature on differences between patients, surrogates, and clinicians on predicting outcomes following critical illness, willingness to pursue treatments that have a low probability of success, and preferences for avoiding certain health states, such as long-term ventilator dependence (Cox et al. 2009; Gramelspacher et al. 1997; Schneiderman et al. 1997). Ethics consultants’ involvement in the final decision with the attending physician, however, did not change the frequency with which the final decision was to limit LST, which may impact their imagined role as an independent third party (Pope 2013).

The variability in the actual practice of ethics consultants’ approaches suggests that, despite increasing proposals for this approach to unrepresented patients, ethics consultants in our institution are not ready to take a consistent and uniform role as independent, third-party decision makers, even if this were a desirable approach. In the three cases in which a best interest standard was identified but ethics consultants made no specific treatment recommendation, the consensus among the treating physician and medical consultants was that death was inevitable regardless of what additional interventions were pursued. Physicians relied on the MGH policy on LST, which was generated in conjunction with the ethics committee, as described above. This suggests an ongoing institutional/hospital policy role for ethics committees, regardless of their involvement in specific cases of decision-making for the unrepresented. Finally, decision-making regarding LST for unrepresented patients may be time sensitive and a revision of the policy requiring that ethics consultants see all unrepresented patients risks duplicating challenges with the timeliness of the guardianship process.

Our study has several limitations. First, this is a medical record review, which limits our ability to create a full portrait of the decision-making process in these cases. Further research would ideally be prospective and interview-based. Second, we do not know about the decision-making process or final decisions for unrepresented patients in which the ethics committee was not consulted. There may have been referral patterns in the types of cases in which the ethics committee was involved that biased the demographics or the final decisions of the attending physician or ethics consultants. Prior studies on this more general question are over ten years old, and an updated prospective analysis would help inform the current discussion about the role of ethics committees more broadly (White et al. 2006; White et al. 2007). Nevertheless, this is the first study to investigate the actual role of an ethics consultant service in decision-making for the unrepresented and our data may inform the ongoing conversations about the appropriate decision makers for this population.

In reflecting more generally on the question of how to allocate surrogate decision-making authority for unrepresented patients, regardless of how this is settled on an institutional level, ethics committees and the involved clinicians and hospital administrators must also consider the legal overlay impacting such decisions in their states. For example, some states include default surrogate decision-making authority in their statutes, making it legally clear how to assess the authority of potential surrogates (American Bar Association 2014). In these states, the ethics committee’s role in identifying an estranged or otherwise previously uninvolved family member will take on added significance, as that individual will not only have potential moral authority to insist on a particular goal of care, but may also have the backing of the legal system in pressing for implementation. In such cases, conflict between the identified surrogate who has default authority and the ethics committee or clinical team recommendation has the added dimension of legal concerns, which should not be ignored, and cannot be replaced simply by deciding, on an institutional level, that ethics committees should be the decision makers in these cases.

In states in which there is no default surrogate decision-making authority provided under the law, including Massachusetts, this dynamic is altered. While family members identified through this process may want to impose their value system and authority as surrogate decision makers, such authority from a legal perspective is not in place. This does not remove them from the process, but it does reduce the risk of noncompliance with their articulated goals of care should it conflict with the ethics committee and/or clinical team determination. Of course, if any such family member or friend should be determined to have a documented and valid healthcare proxy identifying them as the patient’s legal healthcare surrogate (as happened in one case), or should succeed in being named the legal guardian of the patient through a court process, the same considerations identified in the previous paragraph would have to enter into the analysis of how to proceed.

This is not to say that legal considerations should overwhelm or drive how decision-making authority is allocated between the ethics committee and clinicians to determine how to proceed in a particular case, but it should inform the decision. When there are no potential or actual legal healthcare surrogates identified or available, as was the case for many of the patients in this study, the legal risk of not pursuing a guardianship (which would provide clear legal authority for any decision made) is generally considered quite low, and the benefits of allowing for the efficiency of not requiring an extensive legal proceeding to appoint a guardian is often quite high. But the risk is not zero, and, therefore, even in cases in which the patient is unrepresented, legal consultation may be wise to provide a more complete consideration of all the factors that should enter into serious decisions effecting a patient’s life.

Conclusions

In a single centre with an active ethics consultation service, the primary role of ethics consultants in decision-making for the unrepresented was to advise physicians and potential substitute decision makers of appropriate decision-making standards. In the absence of data from other centres suggesting that ethics committees, as currently constituted, are ready to serve directly as substitute decision makers, we believe that caution is necessary before wholly endorsing ethics committees as final decision makers for the unrepresented.

References

Ahluwalia, S.C., J.R. Levin, K.A. Lorenz, and H.S. Gordon. 2012. Missed opportunities for advance care planning communication during outpatient clinic visits. Journal of General Internal Medicine 227(4): 445–451.

American Bar Association. 2014. Default surrogate consents statutes as of June 2014. Available at: http://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/administrative/law_aging/2014_default_surrogate_consent_statutes.authcheckdam.pdf. Accessed November 17, 2015.

Brock, D. 1995. Death and dying: Euthanasia and sustaining life: Ethical issues. In Encyclopedia of Bioethics, edited by E. Reich, 563–572. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Cox, C.E., T. Martinu, S.J. Sathy, et al. 2009. Expectations and outcomes of prolonged mechanical ventilation. Critical Care Medicine 37(11): 2888–2894.

Courtwright, A.M., S. Brackett, W. Cadge, E.K. Krakauer, and E.M. Robinson. 2015. Experience with a hospital policy on not offering cardiopulmonary resuscitation when believed more harmful than beneficial. Journal of Critical Care 30(1): 173–177.

Courtwright, A.M., S. Brackett, A. Cist, M.C. Cremens, E.L. Krakauer, and E.M. Robinson. 2013. The changing composition of a hospital ethics committee: A tertiary care center’s experience. Hospital Ethics Committee Forum 26(1): 59–68.

Gramelspacher, G.P., X.H. Zhou, M.P. Hanna, and W.M. Tierney. 1997. Preferences of physicians and their patients for end-of-life care. Journal of General Internal Medicine 12(6): 346–351.

King, N.M. 1996. The ethics committee as Greek chorus. Hospital Ethics Committee Forum 8(6): 346–354.

Happ, M.B., E. Capezuti, N.E. Strumpf, et al. 2002. Advance care planning and end-of-life care for hospitalized nursing home residents. Journal of the American Geriatrics 50(5): 829–835.

Karp, N., and E. Wood. 2003. Incapacitated and alone: Healthcare decision making for unbefriended older people. Washington, DC: American Bar Association Commission on Law and Aging.

Nalichowski, R., D. Keogh, C.H. Chueh, and S.N. Murphy. 2006. Calculating the benefits of a research patient data repository. American Medical Informatics Association Annual Symposium Proceedings 6(1): 1044.

O’Donnell, H., R.S. Phillips, N. Wenger, J. Teno, R.B. Davis, M.B. Hamel. 2003. Preferences for cardiopulmonary resuscitation among patients 80 years or older: The views of patients and their physicians. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association 4(3): 139–144.

Pope, T.M. 2013. Making medical decisions for patients without surrogates. New England Journal of Medicine 369(21): 1976–1978.

———. 2014. The growing power of healthcare ethics committees heightens due process concerns. Cardozo Journal of Conflict Resolution 15(2): 425–447.

Pope, T., and T. Sellers. 2011. Legal briefing: The unbefriended: Making healthcare decisions for patients without surrogates (Part 2). Journal of Clinic Ethics 23(2): 177–192.

Rubin, E., and A.M. Courtwright. 2013. Medical futility procedures: What more do we need to know? CHEST 144(5): 1707–1711.

Rubin, E., and A.M. Courtwright. 2015. Who should decide for the unrepresented? Bioethics 30(3): 173–180.

Schmidt, T.A., E.A. Olszewski, D. Zive, E.K. Fromme, and S.W. Tolle. 2013. The Oregon physician orders for life-sustaining treatment registry: A preliminary study of emergency medical services utilization. The Journal of Emergency Medicine 44(4): 796–805.

Schneiderman, L.J., R.M. Kaplan, E. Rosenberg, and H. Teetzel. 1997. Do physicians’ own preferences for life-sustaining treatment influence their perceptions of patients’ preferences? A second look. Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics 6(2): 131–137.

Solomon, M.Z., L. O’Donnell, B. Jennings, et al. 1993. Decisions near the end of life: Professional views on life-sustaining treatments. American Journal of Public Health 83(1): 14–23.

Tarzian, A and A.C.C.U.T. Force. 2013. Health care ethics consultation: An update on core competencies and emerging standards from the American Society for Bioethics and Humanities’ core competencies update task force. The American Journal of Bioethics 13(2): 3–13.

Varma, S. and D. Wendler. 2007. Medical decision making for patients without surrogates. Archives of Internal Medicine 167(16): 1711–1715.

Veterans Administration. Protection of patient rights. sec.17.32 Informed consent and advance care planning. http://www.benefits.va.gov/warms/docs/regs/38CFR/BOOKI/PART17/s17_32.DOC. Accessed April 7, 2014.

White, D.B., J.R. Curtis, B. Lo, and J.M. Luce. 2006. Decisions to limit life-sustaining treatment for critically ill patients who lack both decision making capacity and surrogate decision-makers. Critical Care Medicine 34(8): 2053–2059.

White, D.B., J.R. Curtis, L.E. Wolf, et al. 2007. Life support for patients without a surrogate decision maker: Who decides? Annals of Internal Medicine 147(1): 34–40.

White, D.B., A. Jonsen, and B. Lo. 2012. Ethical challenge: When clinicians act as surrogates for unrepresented patients. American Journal of Critical Care 21(3): 202–207.

Williams, M.E., and P.A. Freeman. 2007. Transgender health: Implications for aging and caregiving. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services 18(3–4): 93–108.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding

Support for this research was provided by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (5T32HL007633-30). The sponsors had no role in the design of the study, the collection and analysis of the data, preparation of the manuscript, or the decision to submit the final manuscript for publication.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Courtwright, A.M., Abrams, J. & Robinson, E.M. The Role of a Hospital Ethics Consultation Service in Decision-Making for Unrepresented Patients. Bioethical Inquiry 14, 241–250 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11673-017-9773-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11673-017-9773-1