Abstract

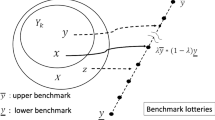

The epistemic modal auxiliaries must and might are vehicles for expressing the force with which a proposition follows from some body of evidence or information. Standard approaches model these operators using quantificational modal logic, but probabilistic approaches are becoming increasingly influential. According to a traditional view, must is a maximally strong epistemic operator and might is a bare possibility one. A competing account—popular amongst proponents of a probabilisitic turn—says that, given a body of evidence, must \(\phi \) entails that \(Pr(\phi )\) is high but non-maximal and might \(\phi \) that \(Pr(\phi )\) is significantly greater than 0. Drawing on several observations concerning the behavior of must, might and similar epistemic operators in evidential contexts, deductive inferences, downplaying and retractions scenarios, and expressions of epistemic tension, I argue that those two influential accounts have systematic descriptive shortcomings. To better make sense of their complex behavior, I propose instead a broadly Kratzerian account according to which must \(\phi \) entails that \(Pr(\phi ) = 1\) and might \(\phi \) that \(Pr(\phi ) > 0\), given a body of evidence and a set of normality assumptions about the world. From this perspective, must and might are vehicles for expressing a common mode of reasoning whereby we draw inferences from specific bits of evidence against a rich set of background assumptions—some of which we represent as defeasible—which capture our general expectations about the world. I will show that the predictions of this Kratzerian account can be substantially refined once it is combined with a specific yet independently motivated ‘grammatical’ approach to the computation of scalar implicatures. Finally, I discuss some implications of these results for more general discussions concerning the empirical and theoretical motivation to adopt a probabilisitic semantic framework.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Current theories of must and might in the same broad family as the conditional account include Kratzer (1981, 1991), Roberts (2015), Moss (2015, 2018) and Del Pinal and Waldon (2019). Relative to those accounts, this paper attempts to make four novel contributions. (i) Present an argument against maximal/minimal accounts which includes novel data on (embedded) epistemic tensions. (ii) Present cases that can be used to discriminate between the threshold-based and the conditional accounts, ultimately supporting the latter. (iii) Develop a novel account of the interaction between epistemic auxiliaries and covert exhaustification operators which improves the predictions of the conditional account relative to our target desiderata. And (iv) provide empirical support for the unique components/stipulations of the conditional account.

For simplicity, we assume that the set of all possible worlds W is finite.

To model maximal and minimal epistemics, an additional assumption is needed. For the finite spaces under consideration, this amounts to a kind of principle of generality amongst the worlds compatible with the evidence, namely, for each \(w \in W\) and \(w' \in E_{e(w)}\), \(Pr_{e(w)}(w')>0\). This ensures that, when modeling epistemics, the corresponding probabilisitic operators don’t (implicitly) exclude epistemic possibilities on non-epistemic grounds such as what is simply believed or assumed.

This is based on a simple adaptation of Yalcin’s (2010) probabilistic version of Kratzer’s semantics for conditionals. The difference is that what is in this case incorporated into the probabilistic space is not an overt antecedent but a contextually provided set of normality assumptions about the world, as determined by g. To keep entries like (5) simple, we will assume that, for each \(w \in W\), g(w) picks out a consistent and non-empty set of normality assumptions.

As discussed in Sect. 2.2, one consequence of the entries in (7) is that certain and possible use the same kind of modal base as must and might. Strictly, we only need to make this assumption for uses of these adjectives in simple unembedded matrix positions like It is certain/possible that p. In addition, this assumption is compatible with the view that the epistemic adverbs certainly and possibly tend to default to more ‘subjective’ modal bases (Lyons 1977; Nuyts 2001) and/or are weaker than their adjectival cousins (see Lassiter 2016).

Since Kratzer (1981), non-maximal/minimal accounts of must and might have had a significant following amongst semanticists who use quantificational frameworks (see, e.g., Roberts 2015; Giannakidou and Mari 2016). Amongst philosophers, Dorr and Hawthorne (2013) allow for ‘constrained’ (non-pure) epistemic readings of the auxiliaries, and Willer (2013) develops a dynamic framework in which might can be modeled as a ‘live possibility’ operator—which is stronger than just ‘bare possibility’ operator. Using Willer’s framework, one can easily formulate a non-maximal dynamic entry for must.

For example, consider a typical every day inference from a set of specific and salient information, such as when S infers on the basis of looking in Google maps that some restaurant is open. This is a typical situation which supports must-claims like McDonald’s must be open—I just checked Google Maps. The salient evidence includes, roughy, ‘S remembers checking the schedule for the target McDonald’s restaurant on Google Maps’, ‘Google Maps said that McDonald’s is open at the relevant time’, and so on. Yet note that the target inference follows from that specific evidence only given some reasonable (yet strictly defeasible) general background assumptions about the world such as ‘If Google Maps says that r is open at t, then r is open at t’, ‘If one has an episodic memory as if p at t, then p happened at t’, and so on.

In some embedded uses of must—esp. under propositional attitudes—the doxastic constraint should be anchored to the relevant subject/s. The details will depend on one’s view of the interaction between epistemic modals and propositional attitudes. For discussion, see Sect. 3.3.

The view that normality assumptions have a doxastic but not an epistemic constraint requires a doxastic and epistemic logic that allows agents to (coherently) reflectively believe propositions that they do not believe they know. Accordingly, the background logics should include (i) the distribution axiom for \(K_i\) and \(B_i\), (ii) veridicity only for \(K_i\), so that \(K_i(\phi )\) asymmetrically entails \(B_i(\phi )\), and (iii) \(B_i\) is weak in the sense that \(B_i(\phi \wedge \Diamond \lnot \phi )\) should be consistent, where \(\Diamond \) stands for simple possibility over a modal base anchored to i. There are various logics for the \(K_i\) and \(B_i\)-operators that respect (i)–(iii). For example, van Benthem and Smets (2015) model \(B_i\) as a universal quantifier over the ‘most plausible’ worlds of epistemic spaces. To cohere with our view, we can assume that if \(g_p\) picks out the premises for a plausibility ordering and g for a stereotypical ordering source, then for each \(w \in W\), \(g(w) \subseteq g_p(w)\), i.e., plausibility orderings can include more information. From this perspective, although an assertion by S of must \(\phi \) entails that \(B_s(\phi )\), S can consistently acknowledge that it is strictly possible that \(\lnot \phi \). As we will see in Sect. 3, this ensures that the conditional account can deal with epistemic tensions in which must \(\phi \) can be conjoined with the bare possibility that \(\lnot \phi \). In short, a relatively weak semantics for \(B_i\) allows us to hold that speakers/interlocutors have to believe, in that sense, the normality assumptions they use even though some of those background assumptions are explicitly/implicitly represented as defeasible. (For additional evidence that believe is weak in roughly this sense, see Hawthorne et al. 2016; Rothschild 2020).

On this implementation of the conditional account—i.e., given our conception of normality assumptions—\(B_s(\phi )\) doesn’t entail \(K_s (must\ \phi )\) or \(B_s (must\ \phi )\). This is because not just any of S’s beliefs count as normality assumptions in a given context c—only those that are part of the common ground in c, i.e. that have the status of mutually held beliefs. S may hold various idiosincratic beliefs that S correctly thinks are not part of the common ground—and can’t be used as background assumptions when reasoning with others about what follows from specific bits of evidence. This prediction is born out in cases like the following. John is anxiously waiting for Peter to arrive at the dinner party. John tends to trust his gut feelings, although he is not so deluded as to think that others would treat his intuitions as reliable indicators. Someone rings the doorbell, John gets the feeling, and says I believe it’s John, but I wouldn’t go so far as to say that it must be/it definitely is him. In scenarios like this, these kinds of epistemic tensions seem quite acceptable.

One could reject this consequence by adopting a simple Lockean theory of belief, such that \(\theta ^{\text {believe}} \le \theta ^{\text {must}}\), but most would agree that this is a costly move.

The p in fact/indeed q test works as intended only if there is independent reason to hold that p and q are in logical relations with each other (cf. Yalcin 2016, pp. 236–237). Accordingly, I am not using this test to argue that, say, \(<must, certain>\) and \(<might, possible>\) stand in logical relations with each other. Rather, I am assuming that they do so stand, at least relative to the contexts used above, and use this test to examine hypotheses about what those relations could be.

Similarly, we would predict that epistemic tensions of the form ‘must \(\phi \) \(\wedge \) might \(\lnot \phi \)’ should be rated as at least as acceptable as tensions of the form ‘must \(\phi \) \(\wedge \) possible \(\lnot \phi \)’. For if use of slack over must is what rescues the latter from strict incoherence, that same mechanism should also rescue the former from the same fate. Yet tensions of the form ‘must \(\phi \) \(\wedge \) possible \(\lnot \phi \)’ were rated as substantially more acceptable than those of the form ‘must \(\phi \) \(\wedge \) might \(\lnot \phi \)’.

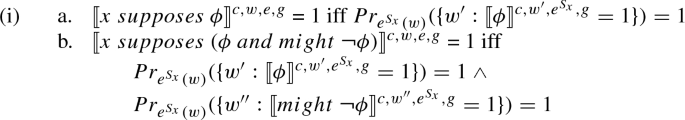

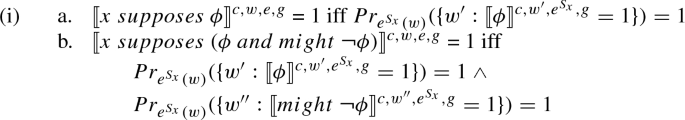

To get a semantic account of the oddness of (23a), why do we appeal to ‘rigidified’ probabilistic spaces? Consider the entry in (i), where \(e^{S_x}(w)\) stands for a probabilistic space that captures what x supposes in w, and in which we don’t further rigidify the probabilistic space used by the modal in the scope of the attitude. Given (ia) and any reasonable entry for might, x supposes (\(\phi \) and might \(\lnot \phi \)) comes out as consistent. This can be seen from the truth-conditions in (ib), which are satisfied in the following situation: x supposes that \(\phi \) in w, so the first conjunct comes out as true, and in addition, x supposes that, in each world compatible with what x supposes in w, x is agnostic about \(\phi \), so the second conjunct also comes out as true.

The reason why, given these assumptions, x supposes (\(\phi \) and might \(\lnot \phi \)) has a consistent reading is this: although a semantic effect of suppose is to shift e to \(e^{S_x}\), still \(Pr_{e^{S_x}(\ )}\) can determine a different probability measure at the evaluation world w and at any world \(w'\) compatible with what is supposed at w. As a result, if we combine any of the entries for might in Sect. 2 with an entry for suppose as in (ia), the oddness of (23a) would have to be given a non-semantic explanation (for attempts, see Roberts 2015; Dorr and Hawthorne 2013).

This account correctly predicts that expressions like x supposes (\(\phi \) and x doesn’t know \(\phi \)) can have coherent readings. This follows from the stipulation that propositional attitudes like suppose/imagines/knows shift the modal space over which they are defined (hence they can also do this when embedded under other attitudes). For a related discussion, see Anand and Hacquard (2013).

As Anand and Hacquard (2013) argue, some propositional attitudes—e.g., hope and doubt—seem to admit possibility but not (weak) necessity epistemic modals. However, attitudes like imagine/suppose/think/believe seem to admit both kinds of epistemic modals. For example, John supposes that it must be raining is acceptable (and arguably subtly different in meaning compared to John supposes that it is raining).

I argued in Sect. 2.4 that an assertion by S of must \(\phi \) typically entails that \(B_S(\phi )\). That result does not conflict with the current explanation of the acceptability of (27a); for recall that we modeled \(B_S(\phi )\) as just requiring that \(\phi \) hold in all of the most plausible worlds. Indeed, in a context like (27), I hope Arsenal won, but I believe they lost feels quite acceptable. For further discussion, see Sect. 5.2.

Some quantificational accounts also stipulate that, in its epistemic use, must \(\phi \) is cross-contextually weak: e.g., Giannakidou and Mari (2016) hold that must \(\phi \) presupposes that \(\phi \) does not hold in all the worlds of the epistemic modal base, and asserts that \(\phi \) holds in all of the ‘best’ worlds of the epistemic modal base.

Contexts in which that assumption is not satisfied are discussed in Sect. 5.2.

Grammatical accounts have various advantages over standard Gricean accounts of scalar implicatures, some of which I discuss below. One that is particularly important for us is that it allows for the triggering of implicatures in (non-asserted) embedded clauses. Interestingly, evidential readings seem to occur in such positions. For example, it is intuitively rather odd to report Ann’s belief state in a scenario like (39) (i.e., when Ann is directly looking at the pouring rain) as Ann believes that it must be raining.

I should point out, however, that a quite similar account can be obtained even if we adopt a more constrained approach such that \(Alt(\phi )\) only includes strictly structural alternatives of \(\phi \). For discussion, see footnote 29.

Independent evidence for the hypothesis that natural languages include a covert epistemic necessity operator is found in recent work arguing that ignorance implicatures should be derived compositionally (Meyer 2013; Buccola and Haida 2019; Marty and Romoli 2021). In addition, as pointed out to me by an editor of L&P, if one adopts a standard Kratzerian semantics for bare indicative conditionals, one also needs to postulate that natural languages include a covert pure (non-evidential) epistemic necessity modal, which can appear as the main modal of bare conditionals. Finally, it is also important to note that Buccola et al. (2021) have recently argued that covert operators can in general be used to form alternatives of expressions with overt operators.

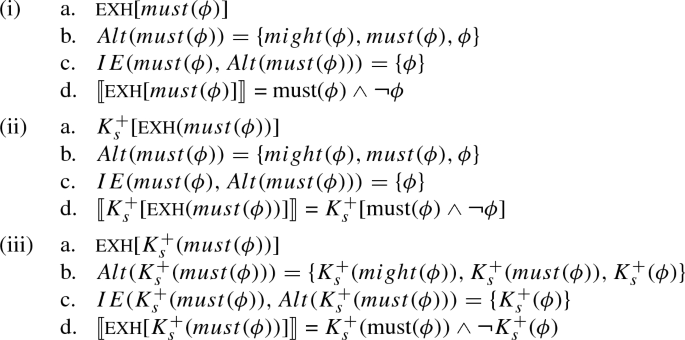

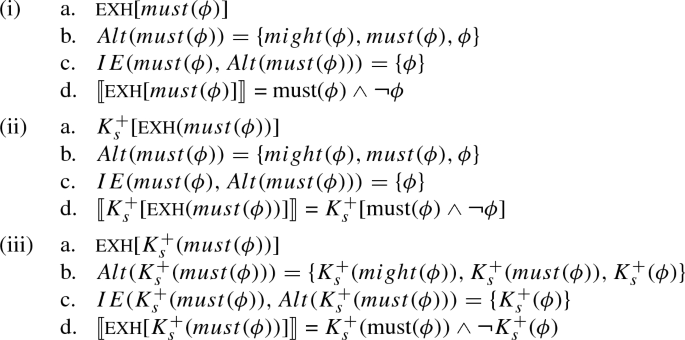

Crucially, a similar result can be derived while assuming a more constrained procedure (e.g., strictly structural one) for determining \(Alt(must (\phi ))\). Yet in this case the grammatical theory has to then be supplemented with the (increasingly popular) hypothesis that ignorance implicatures are derived compositionally via the interaction between exh and a (speaker-centric) epistemic necessity operator \(K^+_i\) (see Meyer 2013; Fox 2016; Buccola and Haida 2019; Marty and Romoli 2021). Suppose exh is obligatory and \(K^+_i\) optional. (42) can then be parsed as in (ia), (iia) or (iiia). The alternatives in each case—i.e., in (ib), (iib), and (iiib)—are either strict scalar alternatives, or obtained through deletion of focused (overt) constituents (cf. Katzir 2007; Fox and Katzir 2011).

Based on each corresponding derivation, it is easy to check that (ia) and (iia) have interpretations that would in general result in incoherent assertions. In contrast, (iiia) supports the coherent reading that the speaker S is certain that \(\phi \) follows from evidence and reasonable (defeasible) assumptions, but is not certain that \(\phi \) follows just from the evidence. This approximates the intuitive reading of must \(\phi \) in contexts like (38), and arguably still predicts a clash, hence the resulting oddness, in contexts like (39), i.e., when the interlocutors are likely to hold that it is part of the common ground that S has the sort of evidence which licenses being certain that \(\phi \).

The conditional plus grammatical account coheres well with other results emphasized in recent work on the evidential patterns of epistemics. First, since Alt is sensitive to salient alternatives, this account is flexible relative to which epistemic operators are excluded, and allows for stronger enrichments than the one obtained by adding the negation of strict epistemic necessity (e.g., enrichments can incorporate, depending on the context, negation of certainty, clarity or obviousness, just like ‘some’ claims can be enriched so as to exclude ‘all’, ‘most’ or ‘half’ claims, depending on the context). Secondly, it predicts that cross-linguistic counterparts of must should follow the same evidential patterns. Third, it predicts that other strong(ish/er) epistemic modals should generate similar evidential patterns (if they also conditionalize on defeasible normality assumptions, in a way that renders them compatible with the negation of strict epistemic necessity). Fourth, it explains why can’t-claims generate evidential patterns similar to those observed for must—at least if it turns out that, in general, can’t \(\phi \) is a spell out of \(\lnot \)might \(\phi \) rather than of \(\lnot \)possible \(\phi \). For example, S can felicitously assert It can’t be raining if S sees people coming in with shorts and dry clothes, but the same assertion would be odd if S is looking directly at the sunny and clear sky. The default LF for such can’t-claims is \(\textsc {exh}[\lnot might(\phi )]\). Since might is a ‘live’ possibility operator, the prejacent is asymmetrically entailed by alternatives such as \(\lnot possible \ \phi \), which will thus be negated by exh when salient and relevant, giving rise to enriched readings along the lines of \(\lnot might \ \phi \wedge possible\ \phi \). The entailment that, given S’s evidence, it’s possible that it’s raining conflicts with what interlocutors will usually take to be in the common ground when S is looking directly at a sunny and clear sky.

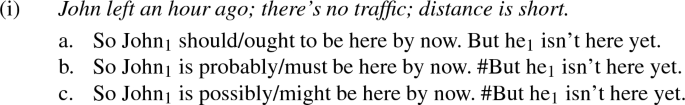

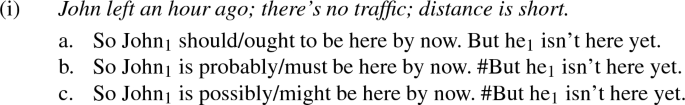

In their original examples, Copley (2004, 2006) and Swanson (2016) focused on the observation that while should \(\phi \) can be conjoined with \(\lnot \phi \), as in (ia), other (genuine) epistemics, including live and bare possibility ones, generate oddness in parallel structures, as illustrated in (ib)–(ic):

Contrasts like the one between (ia) and (ib)–(ic) suggest that ‘should/ought’ (can) have a ‘pseudo-epistemic’ reading—which doesn’t use an epistemic modal base—akin to the account of ‘normally’ defended by Yalcin (2016). From this perspective, should/ought shouldn’t in general be used to set or try to reveal the baseline behavior of strong-ish (but non-maximal) epistemic operators in specific constructions/contexts (as von Fintel and Gillies (2010) sometimes do).

Some readers have pointed out to me that (44d) feels more natural than (44c). This judgment isn’t surprising from the perspective of the conditional plus grammatical account. Strictly speaking, the bare possibility assertion in (44c) is borderline redundant (I say ‘borderline’ because it may still clarify to other interlocutors that S is using a set of normality assumptions that includes defeasible propositions). Redundancy can generate oddness, but the conditions under which it does so are intricate and the judgments usually less strong than in cases of incoherence. Still, from this perspective, the hope-claim in (44d) should feel improved because, although it entails/presupposes that, relative to S’s evidence, it’s strictly possible that John isn’t at the party, it also adds the novel information that S would prefer it if John isn’t at the party (yet), which is obviously not conveyed by the initial must-claim.

To be sure, interlocutors can represent even trivial assumptions as defeasible in special cases, such as in discussions of metaphysics and philosophical logic.

To be clear, I’m not suggesting that the only way to allow for felicitous uses of must-claims in deductive conclusions is via selection of ‘trivial’ normality assumptions (thus blocking the exclusion of any \(\mathcal {E}^+_{i, l}(\phi )\) alternative of must \(\phi \)). Given the conditional plus grammatical package, other possibilities naturally emerge. In some cases, exh can associate, in LFs of the form \(\textsc {exh}[must \ \phi ]\), with (constituents of) \(\phi \), rather than with must: e.g., an assertion of it must be raining\(_\text {F}\) can express (i) that the evidence given background assumptions entails that it is raining and (ii) that it is not the case that they entail that it is, say, snowing. In cases like this, there’s no obligatory enrichment to instances of \(\lnot \mathcal {E}^+_{i,l}(\phi )\). In other cases, the discourse may make it clear that the only relevant alternatives are, say, might vs. must-claims. And since to be considered for exclusion by exh, alternatives of the prejacent should also be relevant, in these cases \(\textsc {exh}[must \ \phi ]\) will not implicate weakness. When considering specific variations of evidential patterns and their interaction with deductive uses, it is important to keep in mind these additional mechanisms for generating enriched readings.

To be sure, this doesn’t exclude the possibility that interlocutors sometimes do tinker with their assignments of normality assumptions precisely to rescue a must-claim that would otherwise be odd or too obviously true/false. This might happen when they are unsure about elements of the common ground, incl. the broad goals/standards/topics of the conversation. Imagine a tourist wandering through a hotel lobby which, unbeknownst to them, is holding a philosophy conference, and trying to make sense of utterances like ‘we all have a visual representation as if it is pouring rain outside; there is no reason to think we are hallucinating in perfect synchrony; so it must be raining’.

To see this, assume at least one of the alternatives in \(\mathcal {E}_{s, 1}^+(\phi ), \ldots , \mathcal {E}_{s, n}^+(\phi )\) is interpreted as semantically entailing both an epistemic necessity claim and an evidential ‘not too obvious or clear or direct’ condition, which we can schematically represent as \(K^+(\phi ) \wedge EV(\phi )\). Negating that we get \(\lnot K(\phi ) \vee \lnot EV(\phi ) \), which can be consistently conjoined with a maximally strong interpretation of must \(\phi \), and the result would be equivalent to \(K^+(\phi ) \wedge \lnot EV(\phi )\). Now, recent work on evidentials suggests that some of the relevant operators—involved in contextually salient alternatives for must—may well have a non-trivial at issue vs. non-at issue/presupposed semantic structure, rather than a flat conjunctive semantic structure (see Murray 2020). This might complicate the previous result when the relevant alternatives are negated (since e.g., the evidential part, \(EV(\phi )\), may project out of negation if modeled as presupposed). However, even assuming that an operator like, say, obviously presupposes rather than asserts either \(K^+(\phi )\) or its \(EV(\phi )\) entailments, we can still maintain the target result by appealing to a local accommodation operator, which may be licensed in fairly standard ways by the pressure to avoid inconsistencies or empty/vacuous applications of exh.

Another option for dealing with patterns like (49)–(50), which is compatible with the conditional plus grammatical account, is to endorse Mandelkern’s proposal directly. This proposal is based on the interaction between the semantics of must (esp., the component which says that the prejacent follows from the relevant/salient evidence) and some independently motived pragmatic constraints (esp., a version of the principle that assertions shouldn’t be redundant given the information in the common ground). From those premises, Mandelkern derives a felicity constraint which says, roughly, that must \(\phi \) assertions are infelicitous if the way in which \(\phi \) follows from the evidence is too obvious to the interlocutors. That explains why (49a) is odd, while (50a) is comparatively better. From the perspective of the conditional plus grammatical account, the premises of Mandelkern’s account are satisfied at least in contexts that result in strong uses of must \(\phi \). Accordingly, such strong uses would be subject to the fully general pragmatic principles that, according to Mandelkern, further restrict their distribution. I won’t try to empirically separate Mandelkern’s original account with the grammatical exh-based implementation I proposed above, but a key difference might be whether we also observe an anti-obviousness constraint in embedded, maximally strong uses of must. For such cases are directly expected on the grammatical account, since exh may appear in embedded positions, but would require some arguably non-trivial modification of the fully pragmatic account so as to get a plausible notion of redundancy relative to local contexts.

Whether this is ultimately a reason to adopt (i) a measure semantics and (ii) a probabilistic one depends on open debates about the logic needed to model epistemics like likely and probably. Yalcin (2010) and Lassiter (2015, 2017) develop measure semantic accounts that respect finite additivity and capture various desirable inference patterns not captured by standard ordering accounts. But Holliday and Icard (2013) show that one can capture the target patterns with a weaker measure semantics with qualitative additivity or an ordering semantics with certain lifting functions.

For example, Santorio and Romoli (2017) implement a probabilistic measure semantics using standard degree semantics, and present an attractive and uniform account of free choice inferences for epistemic adjectives (relying on the scope relations between exh and degree operators). If the auxiliaries are modeled in analogous ways, one could extend their account to free choice inferences with epistemic auxiliaries.

References

Anand, P., & Hacquard, V. (2013). Epistemics and attitudes. Semantics and Pragmatics, 6(8), 1–59. https://doi.org/10.3765/sp.6.8.

Barker, C. (2009). Clarity and the grammar of skepticism. Mind & Language, 24(3), 253–273. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0017.2009.01362.x.

Buccola, B., & Haida, A. (2019). Obligatory irrelevance and the computation of ignorance inferences. Journal of Semantics, 36(4), 583–616. https://doi.org/10.1093/jos/ffz013.

Buccola, B., Kriz, M., & Chemla, E. (2021). Conceptual alternatives: Competition in language and beyond. Linguistics and Philosophy. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10988-021-09327-w.

Cariani, F. (2016). Deontic modals and probabilities: One theory to rule them all? In N. Charlow & M. Chrisman (Eds.), Deontic Modality (pp. 11–46). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Carr, J. (2015). Subjective Ought. Ergo, 2, 678–710. https://doi.org/10.3998/ergo.12405314.0002.027.

Chierchia, G., Fox, D., & Spector, B. (2012). Scalar implicature as a grammatical phenomenon. In C. Maienborn, K. von Heusinger, & P. Portner (Eds.), Semantics: An international handbook of natural language meaning (Vol. III, pp. 2297–2331). Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Copley, B. (2004). So-called epistemic ‘should’. Snippets, 9, 7–88.

Copley, B. (2006). What should ‘should’ mean? Paper presented at Language Under Certainty Workshop, Kyoto University. https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00093569.

Del Pinal, G. (2021). Oddness, modularity, and exhaustification. Natural Language Semantics, 29, 115–158. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11050-020-09172-w.

Del Pinal, G., & Waldon, B. (2019). Modals under epistemic tension. Natural Language Semantics, 27(2), 135–188. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11050-019-09151-w.

DeRose, K. (1991). Epistemic possibilities. The Philosophical Review, 4(100), 581–605.

Dorr, C., & Hawthorne, J. (2013). Embedding epistemic modals. Mind, 122(488), 867–913. https://doi.org/10.1093/mind/fzt091.

Dowell, J. L. (2011). A flexible contextualist account of epistemic modals. Philosopher’s Imprint, 11(14). http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.3521354.0011.014.

Egan, A., Hawthorne, J., & Weatherson, B. (2004). Epistemic modals in context. In G. Preyer & G. Peter (Eds.), Contextualism in philosophy (pp. 131–170). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Fox, D. (2007). Free choice and the theory of scalar implicatures. In U. Sauerland & P. Stateva (Eds.), Presupposition and implicature in compositional semantics (pp. 71–120). New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Fox, D. (2016). On why ignorance might be part of literal meaning: Comments on Marie-Christine Meyer. Handout for MIT Workshop on Exhaustivity.

Fox, D., & Katzir, R. (2011). On the characterization of alternatives. Natural Language Semantics, 19, 87–107. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11050-010-9065-3.

Giannakidou, A. (1999). Affective dependencies. Linguistics and Philosophy, 22(4), 367–421. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005492130684.

Giannakidou, A., & Mari, A. (2016). Epistemic future and epistemic must: Nonveridicality, evidence and partial knowledge. In J. Blaszczak, A. Giannakidou, D. Klimek-Jankowska, & K. Migdalski (Eds.), Mood, aspect and modality: New answers to old questions (pp. 75–117). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Goodhue, D. (2017). Must\(\upphi \) is felicious only if \(\upphi \) is not known. Semantics and Pragmatics, 10(14:EA). https://doi.org/10.3765/sp.10.14.

Hacquard, V. (2010). On the event relativity of modal auxiliaries. Natural Language Semantics, 18(1), 79–114. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11050-010-9056-4.

Harman, G. (1986). Change in view. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Hawthorne, J., Rothschild, D., & Spectre, L. (2016). Belief is weak. Philosophical Studies, 173(5), 1393–1404. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-015-0553-7.

Holliday, W. H., & Icard, T. F. (2013). Measure semantics and qualitative semantics for epistemic modals. Semantics and Linguistic Theory, 23, 514–534.

Karttunen, L. (1972). Possible and must. In J. P. Kimball (Ed.), Syntax and Semantics (pp. 1–20). New York: Academic Press.

Katzir, R. (2007). Structurally-defined alternatives. Linguistics and Philosophy, 30(6), 669–690. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10988-008-9029-y.

Katzir, R. (2014). On the roles of markedness and contradiction in the use of alternatives. In S. P. Reda (Ed.), Pragmatics, semantics and the case of scalar implicatures (pp. 40–71). London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Klecha, P. (2014). Bridging the divide: Scalarity and modality. PhD thesis, University of Chicago.

Kratzer, A. (1981). The notional category of modality. In H. Eikmeyer & H. Reiser (Eds.), Words, worlds, and contexts: New approaches in word semantics (pp. 38–74). Berlin: De Gruyter.

Kratzer, A. (1991). Modality. In A. von Stechow & D. Wunderlich (Eds.), Semantics: An international handbook of contemporary research (pp. 639–650). Berlin: De Gruyter.

Kratzer, A. (2012). Modals and conditionals. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Krifka, M. (1999). At least some determiners aren’t determiners. In K. Turner (Ed.), The semantics/pragmatics interface from different points of view (pp. 257–291). Amsterdam: Elsevier Science Publishers.

Lasersohn, P. (1999). Pragmatic halos. Language, 75(3), 522–551. https://doi.org/10.2307/417059.

Lassiter, D. (2015). Epistemic comparison, models of uncertainty, and the disjunction puzzle. Journal of Semantics, 32(4), 649–684. https://doi.org/10.1093/jos/ffu008.

Lassiter, D. (2016). Must, knowledge, and (in)directness. Natural Language Semantics, 24(2), 117–163. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11050-016-9121-8.

Lassiter, D. (2017). Graded modality: Qualitative and quantitative perspectives. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Lyons, J. (1977). Semantics. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

MacFarlane, J. (2011). Epistemic modals are assessment-sensitive. In A. Egan & B. Weatherson (Eds.), Epistemic modality (pp. 144–178). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Magri, G. (2009). A theory of individual-level predicates based on blind mandatory scalar implicatures. Natural Language Semantics, 17(3), 245–297. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11050-009-9042-x.

Magri, G. (2011). Another argument for embedded scalar implicatures based on oddness in downward entailing environments. Semantics and Pragmatics, 4(6), 1–51. https://doi.org/10.3765/sp.4.6.

Magri, G. (2014). Two puzzles raised by oddness in conjunction. Journal of Semantics, 33(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1093/jos/ffu011.

Magri, G. (2017). Blindness, short-sightedness, and Hirschbergs contextually ordered alternatives, a reply to Schlenker. In S. Pistoia Reda & F. Domaneschi (Eds.), Linguistic and psycholinguistic approaches on implicatures and presuppositions (pp. 9–54). New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Mandelkern, M. (2016). A solution to Karttunen’s problem. Proceedings of Sinn und Bedeutung, 21(2), 827–844. https://doi.org/10.18148/sub/2018.v21i2.170.

Mandelkern, M. (2019). What ‘must’adds. Linguistics and Philosophy, 42(3), 225–266. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10988-018-9246-y.

Marty, P., & Romoli, J. (2021). Presupposed free choice and the theory of scalar implicatures. Linguistics and Philosophy. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10988-020-09316-5.

Mayr, C. (2013). Implicatures of modified numerals. In I. Caponigro & C. Cecchetto (Eds.), From grammar to meaning: The spontaneous logicality of language (pp. 139–171). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Meyer, M. C. (2013). Ignorance and grammar. PhD thesis, MIT.

Moss, S. (2015). On the semantics and pragmatics of epistemic vocabulary. Semantics and Pragmatics, 8(5), 1–81. http://doi.org/10.3765/sp.8.5.

Moss, S. (2018). Probabilistic knowledge. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Murray, S. E. (2020). Evidentiality, modality, and speech acts. Annual Review of Linguistics, 7, 213–233.

Ninan, D. (2018). Relational semantics and domain semantics for epistemic modals. Journal of Philosophical Logic, 47(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10992-016-9414-x.

Nuyts, J. (2001). Subjectivity as an evidential dimension in epistemic modal expressions. Journal of Pragmatics, 33(3), 383–400. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-2166(00)00009-6.

Portner, P. (2009). Modality. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Roberts, C. (2015). The character of epistemic modality: Evidentiality, indexicality, and what’s at issue. Ms., Ohio State University.

Rothschild, D. (2020). What it takes to believe. Philosophical Studies, 177, 1345–1362. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-019-01256-6.

Rudin, D. (2020). Deriving a variable-strength might. Proceedings of Sinn und Bedeutung, 20, 587–603. https://ojs.ub.uni-konstanz.de/sub/index.php/sub/article/view/283.

Santorio, P., & Romoli, J. (2017). Probability and implicatures: A unified acccount of the scalar effects of disjunction under modals. Semantics and Pragmatics. https://doi.org/10.3765/sp.10.13.

Stalnaker, R. (2014). Context. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Stephenson, T. (2007). Judge dependence, epistemic modals, and predicates of personal taste. Linguistics and Philosophy, 30(4), 487–525. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10988-008-9023-4.

Stone, M. (1984). The reference argument for epistemic must. In H. Bunt, R. Muskens, & G. Rentier (Eds.), International Workshop on Computational Semantics (pp. 181–190). Tilburg: Tilburg University.

Swanson, E. (2006). Interactions with context. PhD thesis, MIT.

Swanson, E. (2010). Structurally-defined alternatives and lexicalizations of XOR. Linguistics and Philosophy, 33(1), 221–242. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10988-010-9074-1.

Swanson, E. (2011). How not to theorize about the language of subjective uncertainty. In A. Egan & B. Weatherson (Eds.), Epsitemic modality (pp. 249–269). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Swanson, E. (2016). The application of constraint semantics to the language of subjective uncertainty. Journal of Philosophical Logic, 45(2), 121–146. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10992-015-9367-5.

Swanson, E. (2017). Omissive implicatures. Philosophical Topics, 45(3), 117–137. https://doi.org/10.5840/philtopics201745216.

van Benthem, J., & Smets, S. (2015). Dynamic logics of belief change. In H. van Ditmarsch, J. Y. Halpern, W. van der Hoek, & B. Kooi (Eds.), Handbook of epistemic logic (pp. 313–385). Milton Keynes, UK: College Publications.

von Fintel, K., & Gillies, A. S. (2010). Must... stay... strong! Natural Language Semantics, 18(4), 351–383. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11050-010-9058-2.

von Fintel, K., & Gillies, A. S. (2021). Still going strong. Natural Language Semantics, 29, 91–113. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11050-020-09171-x.

Waldon, B. (2021). Epistemic must and might: Evidence that argumentation is semantically encoded. Paper presented at the 56th Annual Meeting of the Chicago Linguistic Society (CLS), virtual only.

Willer, M. (2013). Dynamics of epistemic modality. Philosophical Review, 122(1), 45–92. https://doi.org/10.1215/00318108-1728714.

Yalcin, S. (2007). Epistemic modals. Mind, 116(464), 983–1026. https://doi.org/10.1093/mind/fzm983.

Yalcin, S. (2010). Probabilistic operators. Philosophy Compass, 5(11), 916–937. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-9991.2010.00360.x.

Yalcin, S. (2016). Modalities of normality. In N. Charlow & M. Chrisman (Eds.), Deontic modality (pp. 230–255). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Acknowledgements

For many helpful discussions, I would like to thank Gabe Dupre, Brian H. Kim, Eleonore Neufeld, Calum McNamara, Matt Mandelkern, Uli Sauerland and Brandon Waldon. Special thanks to Elise Woodard for a crucial suggestion that led to a substantial refinement of my account of evidential patterns, and to Paolo Santorio, Eric Swanson and two anonymous reviewers for L&P for many incisive comments and suggestions on various drafts of this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Del Pinal, G. Probabilistic semantics for epistemic modals: Normality assumptions, conditional epistemic spaces and the strength of must and might. Linguist and Philos 45, 985–1026 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10988-021-09339-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10988-021-09339-6