Abstract

Inconsistent information between an organization’s corporate social responsibility (CSR) commitments and perceived CSR (in-)action is a big challenge for organizations because this is typically associated with perceptions of corporate hypocrisy and related negative stakeholder reactions. However, in contrast to the prevailing corporate hypocrisy literature we argue that inconsistent CSR information does not always correspond to perceptions of corporate hypocrisy; rather, responses depend on individual predispositions in processing CSR-related information. In this study, we investigate how an individual’s moral identity shapes reactions to inconsistent CSR information. The results of our three studies show that individuals who symbolize—i.e., display—their moral identity to the public more than they internalize moral values react less negatively to inconsistent CSR information. We also show that this weakens their anger and willingness to change company behavior. Furthermore, we find that this effect is amplified for extraverted but weakened for neurotic individuals. Our findings underline the importance of individual predispositions in processing CSR information.

Similar content being viewed by others

Companies often face negative publicity about their business practices if they contradict their public corporate social responsibility (CSR) commitments. So far, research has traditionally assumed that such inconsistent CSR information leads to corporate hypocrisy perceptions (e.g., Wagner et al., 2009, 2019), defined as “the belief that a firm claims to be something that it is not” (Wagner et al., 2009, p. 79). Typically, individuals who become aware that they are not practicing what they preach consider themselves hypocrites because of the dissonance of the two cognitions they hold (Aronson et al., 1991). This reasoning also applies when judging others, including organizations (e.g., Hinojosa et al., 2017). Therefore, it is commonly assumed that reading inconsistent CSR information creates a sense of cognitive dissonance in the readers’ mind, inducing perceptions of corporate hypocrisy (Wagner et al., 2009, 2019). In this context, corporate hypocrisy research has traditionally been interested in how CSR communication characteristics affect perceived corporate hypocrisy (Bartikowski & Berens, 2021; de Jong et al., 2020; Higgins et al., 2020; Wagner et al., 2009), such as linguistic formulations (Higgins et al., 2020) and message framing (Bartikowski & Berens, 2021).

Lately, scholars have advanced this view by addressing the subjectivities involved in hypocrisy perceptions (Chen et al., 2020; Effron & Miller, 2015; Effron et al., 2018; Helgason & Effron, 2022; Lauriano et al., 2021). For example, Effron et al. (2018) suggested that, among other factors, motivation and chronic vigilance determine whether individuals detect word-deed misalignment, and that individuals interpret misalignment as hypocritical only if they consider it as an unearned moral benefit. Others focus on individuals’ moral judgments (Lauriano et al., 2021), CSR motive attributions (Chen et al., 2020), or the emotional reactions of the transgressor (Effron & Miller, 2015). These insights suggest that hypocrisy perceptions are to a certain extent subjective and vary among individuals. Individual predispositions seem to play a crucial role, even though this has not been the focus of corporate hypocrisy research.

We argue that the explicit consideration of individual predispositions is important because individuals judge organizations’ inconsistencies in relation to how they view themselves (Hinojosa et al., 2017; Norton et al., 2003). Furthermore, individual predispositions do, often unconsciously, affect the tendency to judge information more positively or negatively (Rusting, 1999). We take these aspects into account in two ways. First, and building on the findings that hypocrisy perceptions involve a moral component, we argue that one’s moral identity—the extent to which an individual defines him or herself in relation to moral traits (Aquino & Reed, 2002)—is an essential individual predisposition that affects reactions to inconsistent CSR information. The literature on moral identity distinguishes between a private and a public dimension. The private dimension—internalization—captures the extent to which moral characteristics are part of one’s self-definition. The public dimension—symbolization—is the perceived importance of conveying a moral self to the public through visible words or action (Aquino & Reed, 2002). Individuals’ symbolization level may exceed their internalization level to corroborate their moral identity to others (Skarlicki et al., 2008; Winterich et al., 2013a, 2013b). This is not surprising, because many individuals seek to be seen positively by others (Vallas & Cummins, 2015) and to impress others with moral acts (Aquino & Reed, 2002). Hence, it is important to investigate how these individuals perceive and react to organizational information. Second, personality traits more generally influence how individuals process information. Specifically, the personality traits of extraversion and neuroticism reveal an individual’s tendency to process information more positively (in the case of extraversion) or more negatively (in the case of neuroticism) (Rusting, 1999).

We draw on these insights and focus on individuals who have higher levels of symbolization than internalization, which we hereafter label symbolized moral identity. Based on cognitive dissonance theory (CDT), we unpack how and why individuals with a symbolized moral identity are less willing to counteract a company’s potentially questionable business practices in response to inconsistent CSR information. According to CDT, individuals strive for consistency between two cognitions. If two cognitions conflict, a cognitive dissonance arousal and reduction process is initiated (Hinojosa et al., 2017). In our case, the two cognitions involve how individuals view themselves and the respective organizations. An awareness of such cognitive discrepancies is commonly associated with hypocrisy perceptions, which is the starting point of the cognitive dissonance arousal process (Fried & Aronson, 1995). This dissonance arousal, in turn, triggers affective reactions (Hinojosa et al., 2017). We investigate anger as an affective reaction to cognitive dissonance. We do so because it is a morally laden affective state that is likely to be induced in situations that demand moral judgments, such as the CSR context (Chen et al., 2020; Lauriano et al., 2021). Finally, a central premise of CDT is that individuals are motivated to reduce that cognitive dissonance. Common action tendencies involve attempting to change one of the conflicting factors (Hinojosa et al., 2017). We focus on constructive punitive action—an action tendency that aims at positively changing a company’s behavior (Romani et al., 2013). Overall, we argue that inconsistent CSR information is less likely to induce cognitive discrepancy in individuals with a symbolized moral identity because inconsistent CSR information signals to them that an organization has a similar character to theirs, inducing weaker affective reactions and a reduced willingness to engage in constructive punitive action. Furthermore, we posit that this process is influenced by how individuals process information in general and therefore their degree of extraversion and neuroticism.

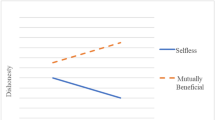

We test our assumptions through three studies (see Fig. 1). Study 1 and 2 involve exposing participants to inconsistent CSR information and investigating the relation between symbolized moral identity, perceived corporate hypocrisy (Study 1), and subsequent outcomes (Study 2). In Study 3, we test our assumption using a between-subjects experimental design, differentiating between exposure to either consistent or inconsistent CSR information. We examine whether inconsistent CSR information really matters for those individuals with a symbolized moral identity in relation to perceiving an organization as less hypocritical. We slightly modify our model from Study 1 and 2: We include CSR information as the independent variable and symbolized moral identity as the moderator. We also test for three-way interaction with the personality traits of extraversion and neuroticism.

Our contribution is threefold. First, the corporate hypocrisy literature has started to acknowledge the subjectivities involved in corporate hypocrisy perceptions (e.g., Effron et al., 2018; Lauriano et al., 2021). We build on this research stream by providing insight into how individual predispositions matter in hypocrisy perceptions and the related individual-level positive or negative reactions to organizations. Second, while the corporate hypocrisy literature considers the experience of cognitive dissonance a central element in the corporate hypocrisy context (Wagner et al., 2019), we dive deeper into the cognitive dissonance arousal and reduction process (Hinojosa et al., 2017) to explain reactions to inconsistent CSR information. Third, we advance corporate hypocrisy and moral identity research by clarifying how individuals with a symbolized moral identity process inconsistent CSR information.

Conceptual Framework and Hypotheses Development

Inconsistent CSR information refers to “deviation between public CSR statements and business practices disclosed by other sources” (Wagner et al., 2009, p. 78). It is one way through which individuals may detect misalignment between a company’s ‘walk and talk.’ One form of inconsistent CSR information is when a positively valenced public company statement about CSR deviates from a negatively valenced business practice disclosed by other sources. This form of inconsistent CSR information is widespread: Many firms publicly express commitment to CSR to protect themselves from potentially negative publicity (Wagner et al., 2009), which at the same time invites the public to take a closer look at their promises and often leads to contradictory statements.

It is commonly assumed that if individuals read inconsistent CSR information they perceive organizations as hypocritical—i.e., as portraying something they are not (Wagner et al., 2009, 2019). Being confronted with two diverse pieces of information induces perceptions of cognitive dissonance (Wagner et al., 2019). Moreover, cognitive dissonance arises when new information contradicts individuals’ prior beliefs (Straits, 1964). This also holds true when a prior belief about a company (e.g., derived from reading a positively valenced CSR statement) contradicts current information regarding its business practices (e.g., due to reading about negatively valenced practices).

In this regard, many studies have investigated how different forms of CSR communication mitigate or strengthen perceived corporate hypocrisy (e.g., Bartikowski & Berens, 2021; de Jong et al., 2020; Higgins et al., 2020). For instance, the order of the presentation (coming before or after contradictory statements) and the content (abstract versus concrete) of the CSR information shape corporate hypocrisy perceptions (Wagner et al., 2009). Positively framed messages trigger positively valenced memories in people’s minds, which spill over to evaluations of companies (Bartikowski & Berens, 2021). Missing clarity and accuracy in CSR communication increase suspicions of duplicity and that the company is telling lies about its operations (Higgins et al., 2020). In turn, corporate hypocrisy perceptions lead to negative outcomes such as negative customer satisfaction (Ioannou et al., 2022) and negative brand and company evaluations (Wagner et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2020). Hypocrisy perceptions can also negatively impact employees’ voluntary contributions to a company’s CSR program (Babu et al., 2020) and increase emotional exhaustion (Scheidler et al., 2019).

Recently, research has scrutinized how individuals process inconsistent information (Chen et al., 2020; Effron & Miller, 2015; Effron et al., 2018; Helgason & Effron, 2022; Lauriano et al., 2021). Effron et al. (2018) suggest that different aspects (e.g., motivation, chronic vigilance) determine whether individuals detect word-deed misalignment. Similarly, in a CSR context, Lauriano et al. (2021) advanced these insights by explaining that employees undertake case-by-case analysis of misalignments. Some instances of misalignment may be rationalized and not perceived as unearned moral benefit. Moreover, employees evaluate the moral status of inconsistent CSR information by resorting to consequentialist or deontological reasoning. Furthermore, if the person who commits a misdeed has personally suffered from it, this person is perceived as less hypocritical (Effron & Miller, 2015). These insights highlight the role of subjective perceptions and indicate that individual predispositions may play a key role in how individuals perceive corporate hypocrisy. In the following sections, we focus on the role of moral identity and the personality traits of extraversion and neuroticism in shaping individuals’ corporate hypocrisy perceptions and related affective and behavioral outcomes.

Moral Identity as an Individual Predisposition: Internalization and Symbolization

The reaction to others’ inconsistencies depends on one’s predisposition (Eddie Harmon-Jones & Mills, 2019; Norton et al., 2003). In particular, individuals tend to judge others more critically when their values do not align with their own identity (Norton et al., 2003)—the definition one has about oneself (Erikson, 1964). While an individual can ‘wear’ many identities, in this paper we focus on moral identity: We do so because moral identity is crucial for processing CSR-related information (e.g., Rupp et al., 2013), and it is important to further investigate the distinctiveness of the moral identity of individuals in relation to shaping reactions to inconsistent CSR information.

Scholars distinguish between a private and public dimension of moral identity (Aquino & Reed, 2002; Aquino et al., 2009). Internalization—the private aspect of moral identity—is the degree to which moral traits are part of one’s inner self (Aquino & Reed, 2002). This captures the constant, subjective experience of moral concerns and the extent to which a person uses morality to evaluate and act in the environment (Aquino & Reed, 2002; Aquino et al., 2009). Symbolization—the public aspect of moral identity—“taps a more general sensitivity to the moral self as a social object whose actions in the world can convey that one has these characteristics” (Aquino & Reed, 2002, p. 1436). It is an individual’s perceived importance to convey a moral self to the public visibly. Individuals may possess a public and private moral identity to varying degrees (Cheek & Briggs, 1982).

Individuals with high levels of internalization systematically include moral concerns in their judgments of situational cues. They strongly desire others to internalize moral values (Winterich et al., 2013a, 2013b). Therefore, they are more aware of morally laden behavior and events (Aquino et al., 2011). Such individuals are skeptical of others’ public expressions of moral commitment and have little comprehension of others’ moral transgressions (Wiltermuth et al., 2010) and questionable behaviors (Clouse et al., 2017) because such actions threaten their self-identity (Wojciszke, 2005). These individuals also show concern for others (e.g., Reed II and Aquino, 2003). If they see others suffer, they react emotionally (e.g., Barclay et al., 2014).

Individuals with high levels of symbolization aim to make their moral efforts visible to the public (Aquino & Reed, 2002). Often, they want to impress others (Aquino & Reed, 2002) or meet external demands (McFerran et al., 2010). Publicly expressing moral commitment aligns with their self-identity (van Gils & Horton, 2019). These individuals praise others for their good acts without necessarily questioning their intentions (Wiltermuth et al., 2010). They are also more likely to tolerate the morally questionable behavior of others. By frequently engaging in public manifestations of moral identity, they believe in building up ‘moral credits’ (Sachdeva et al., 2009). Hence, the occasional missteps of others they identify with are considered justifiable (Kouchaki, 2011). Tolerance for others’ questionable behavior is particularly pronounced when these individuals are not directly affected, as it does not threaten their self-identity (Barclay et al., 2014; Skarlicki et al., 2008).

Individuals engage in publicly demonstrating their moral identity “to either highlight their true morality or instead mislead people about the value they place on morality […]” (Ormiston & Wong, 2013, p. 869). Individuals who strongly symbolize their moral identity may internalize those moral values within their self-concept (i.e., have balanced and high levels of internalization and symbolization). They may also present a public persona that they do not stand for to the same extent in private (i.e., higher levels of symbolization than internalization). Such individuals have, as described before, a symbolized moral identity. They place greater importance on publicly visible words and actions regarding morality than on living according to these values in their private actions (Winterich et al., 2013a, 2013b). Their motivation to impress others with moral acts outweighs the internalization of moral values.

In the following, we discuss how individuals with a symbolized moral identity react to inconsistent CSR information using CDT (Festinger, 1957; Hinojosa et al., 2017). As discussed before, the central assumption of the theory is that individuals strive for consonance between cognitions. If two cognitions conflict, a cognitive dissonance arousal and reduction process is activated (Hinojosa et al., 2017): When individuals experience cognitive dissonance (i.e., a negative affective state) they tend to reduce it. As we will argue below, this process is less pronounced for individuals with a symbolized moral identity when confronted with inconsistent CSR information because such information signals that the respective organization is similar to themselves. Figure 2 depicts the dissonance arousal and reduction process in relation to the present case.

Process of dissonance arousal and reduction, based on Hinojosa et al. (2017)

The Reaction to Inconsistent CSR Information of an Individual with a Symbolized Moral Identity

The cognitive dissonance arousal and reduction process starts with comparing how the individual views an organization and the self. Inconsistent CSR information affects how individuals view organizations by signaling two things: First, a positively valenced public CSR statement gives individuals an indication that an organization has the drive to communicate its moral and social values and is acting publicly. Second, a negatively valenced business practice revealed by the media provides individuals with cues that the company may not consistently practice what it preaches. Individuals may perceive such inconsistent CSR information as symbolizing a moral character more than internalizing moral values in internal business practice.

Consequently, we propose that individuals with a symbolized moral identity perceive inconsistent CSR information less negatively. Inconsistent CSR information aligns with how individuals with a symbolized moral identity view themselves and signals a valid identity claim for them. They are more likely to believe that a firm is what it pretends to be. This indicates that what individuals believe about themselves and about an organization is less likely to conflict. Also, individuals with a symbolized moral identity are less likely to question others’ moral commitments (e.g., public CSR statements). They are less critical of others’ potential moral transgressions (e.g., in the case of potential scandals), especially when they are not directly affected. For them, word-deed misalignment is less likely to indicate unearned moral benefit (Effron et al., 2018). They may even rationalize a company’s misdeeds in this particular situation (Lauriano et al., 2021). Thus, we argue that individuals with a symbolized moral identity are less likely to interpret inconsistent information as hypocritical firm behavior.

Hypothesis 1 (H1)

Symbolized moral identity is negatively related to perceived corporate hypocrisy in response to inconsistent CSR information.

Perceived Corporate Hypocrisy, Anger, and the Willingness to Engage in Constructive Punitive Action

As indicated in Fig. 2, a conflict between two cognitions arouses cognitive dissonance and subsequent efforts to reduce this dissonance. Adapted to our case, we posit that perceived corporate hypocrisy arouses feelings of anger and a subsequent willingness to engage in constructive punitive action to reduce dissonance. As argued above, this arousal and reduction process, however, is less likely for individuals with a symbolized moral identity. If we turn to the moral identity literature, we would probably expect the opposite because high levels of symbolization are typically associated with different forms of prosocial behavior (Aquino & Reed, 2002; Gotowiec & van Mastrigt, 2019; Schaumberg & Wiltermuth, 2014; Winterich et al., 2013a, 2013b). For instance, research suggests that such individuals are likely to engage in prosocial behaviors that are visible to others (e.g., volunteering) because they usually want to impress (Aquino & Reed, 2002) and obtain recognition from others (Winterich et al., 2013a, 2013b). In contrast, a recent study found that more private social behaviors (e.g., donating money anonymously) may also be pronounced among individuals who rate high on symbolization (Gotowiec & van Mastrigt, 2019). This aligns with insights that symbolization is not only about appearing moral, but also about feeling moral (Schaumberg & Wiltermuth, 2014). However, we posit that this relationship is not as straightforward when the prosocial behavior is a reaction to a company’s potential misdeeds. Here, it matters whether the company’s potential misdeeds contrast with how individuals view themselves.

CDT suggests that the conflict of two cognitions elicits cognitive dissonance. In our case, we posit that perceptions of corporate hypocrisy make individuals more likely to feel angry with a company. Hypocrisy perceptions may foster morality-related emotions directed towards a company (Haidt, 2003), one of which is anger (Lefebvre & Krettenauer, 2019). Anger is a strong, subjectively experienced negative affective state (Averill, 1983; Smith & Lazarus, 1990). The main distinction from other negative affective states (e.g., guilt) is that anger “arises when someone else is being blamed for a harmful situation” (Smith & Lazarus, 1990, p. 620). A person typically becomes angry with a company if a situation is perceived as follows: First, the person believes that the organization is responsible for a specific situation (Kim et al., 2021). Second, the person does not feel in control of the situation (Watson & Spence, 2007). Third, the event involves unfair treatment of others (Batson & Kennedy, 2007). In our case, the event represents the hypocritical behavior individuals perceive in response to inconsistent CSR information. Firms are often held responsible for their hypocritical behavior (Kim et al., 2021). Also, individuals who observe such apparently hypocritical behavior cannot control the situation because the event has already happened and cannot be reversed. Finally, hypocritical behavior is typically perceived as morally wrong because it concerns potential negatively valenced business practices that involve the mistreatment of other stakeholders (Wagner et al., 2009). Empirical evidence suggests that perceived ethical transgressions (Grappi et al., 2013) and hypocrisy perceptions (Laurent et al., 2014) increase feelings of anger. In contrast, we anticipate that for individuals with a symbolized moral identity, feelings of anger are less pronounced because they perceive inconsistent CSR information as less hypocritical.

The final stage of the cognitive dissonance arousal and reduction process concerns individuals’ efforts to reduce cognitive dissonance. Common strategies for reducing such dissonance involve altering one of the two cognitions one holds (Hinojosa et al., 2017). An individual may urge the other party to change its behavior, attitude, or values that cause the dissonance (Festinger, 1957; Hinojosa et al., 2017). In particular, we suggest that anger has a corrective function by eliciting the intention to restore moral standards (Fischer & Roseman, 2007). Therefore, we posit that anger elicited through perceptions of corporate hypocrisy motivates individuals to engage in constructive punitive action (see Romani et al., 2013). Constructive punitive action entails “changing wrong policies and practices of companies [in] the hope of continuing the relationship with them in a positive way” (Romani et al., 2013, p. 1031). Such action, for instance, includes signing a petition or engaging in temporary boycotts (Romani et al., 2013). Constructive punitive action is likely to occur when the event could have been avoided (Nyer, 1997; Watson & Spence, 2007) and when a target can be held responsible. This responsibility attribution happens when companies are accused of violating moral standards. Indeed, anger often elicits behaviors that push the offender in the ‘right direction’ (Fischer & Roseman, 2007). Anger can induce prosocial action tendencies (Haidt, 2003), even though this means temporarily punishing a firm for its immoral actions. Moreover, seeking the social support of others through constructive behavior is a common dissonance reduction strategy (McGrath, 2017). Taken together, we assume that the stronger an individual’s symbolized moral identity, the less pronounced their perceptions of corporate hypocrisy and the weaker their feelings of anger, which in turn lead to less willingness to engage in constructive punitive action.

Hypothesis 2 (H2)

Symbolized moral identity is negatively related to perceived corporate hypocrisy in response to inconsistent CSR information, which relates to weaker feelings of anger and less willingness to engage in constructive punitive action.

Inconsistent versus Consistent CSR Information

Although we have argued so far that individuals with a symbolized moral identity perceive organizations as less hypocritical, we are also aware that the context matters and that such individuals are not immune to inconsistent information. Put differently, even though inconsistent CSR information signals to them an organizational identity that more closely aligns with their own identity, they are still cognizant that there are potential incongruences in organizational communication and action. Research has consistently shown that inconsistent CSR information induces perceptions of corporate hypocrisy (e.g., Bartikowski & Berens, 2021; Wagner et al., 2009). Consequently, the former individuals will perceive such organizations as more hypocritical than those not confronted with conflicting accounts related to their CSR practices. Similar to individuals who are aware of their incongruencies and realize that they act hypocritically from time to time (Ormiston & Wong, 2013), they will also perceive such organizations as more hypocritical than organizations whose words and deeds seem to align.

However, we argue that the stronger the individuals’ symbolized moral identity, the less pronounced the differences in corporate hypocrisy perceptions between organizations confronted with inconsistent CSR information and organizations with consistent CSR information (i.e., positively valenced CSR statements followed by positively valenced CSR behavior). In other words, a symbolized moral identity weakens the relation between inconsistent CSR information (compared to consistent CSR information) and perceptions of corporate hypocrisy.

Hypothesis 3 (H3)

CSR information and symbolized moral identity interact such that the stronger an individual’s symbolized moral identity, the less the difference in the perception of corporate hypocrisy of organizations associated with inconsistent CSR information versus organizations with consistent CSR information.

Combining Hypothesis 3 with the subsequent outcomes, we conclude the following:

Hypothesis 4 (H4)

The stronger an individual’s symbolized moral identity, the weaker the indirect relationship between inconsistent CSR information (compared to consistent CSR information) and willingness to sign a petition via perceived corporate hypocrisy and anger.

Additional Moderating Effects of Personality Traits: The Role of Neuroticism and Extraversion

Apart from one’s identity, personality traits influence the way individuals think, process information, and form judgments (Rusting, 1999). Therefore, personality traits may affect how individuals process inconsistent CSR information. Much of the research that has investigated the role of cognitive information processing is related to the two traits of extraversion and neuroticism. Extraverted individuals are sociable, adventurous, outgoing, and positive. In contrast, neurotic people are anxious, shy, moody, and not self-confident (John & Srivastava, 1999). Extraverted people generally experience positive affect, while neurotic people experience negative affect (Gomez et al., 2002).

According to the trait-congruence hypothesis (Rusting, 1999), individuals process information that is “congruent in […] emotional tone with their personality traits” (Rafienia et al., 2008, p. 393). Rusting (1999) provides a possible explanation for this relationship based on Bower’s (1981) network theory of affect: Extraverted people are likely to recall positive memories, thoughts, and beliefs in their minds when making judgments, while neurotic people are likely to recall negative memories related to that information when making judgments (Bower, 1981). According to this logic, extraverted people tend to make more positive judgments, and neurotic ones more negative judgments (Rusting, 1999).

Individuals may possess high levels of extraversion and neuroticism simultaneously, or rate low on both personality traits. According to Eysenck and Eysenck (1985), a combination of extraversion and neuroticism is decisive in terms of the degree of affective reaction. Neurotic extraverts (i.e., individuals high on extraversion and neuroticism) and stable introverts (i.e., individuals low on extraversion and neuroticism) dispose of a neutral affective home base. A neutral affective home base means that these individuals, on average, have neutral affective experiences. Those disposing of discrepant levels of neuroticism and extraversion tend to have a positive affective home base in the case of high extraversion and a negative affective home base in the case of high neuroticism. Therefore, we suggest that the trait-congruence effect tends to apply to individuals who rate high either on extraversion or neuroticism.

We posit that this trait-congruence effect is particularly relevant in the context of inconsistent CSR information. Individuals form judgments that align with their traits, especially when confronted with ambiguous information that leaves space for individual interpretation. Furthermore, emotional information can induce trait-congruent judgments (Rusting & Larsen, 1998). Inconsistent CSR information is ambiguous because of conflicting information about a company’s CSR efforts and has an emotional component because of the moral character of CSR (Wagner et al., 2019).

We propose that highly extraverted people who possess a symbolized moral identity will perceive organizations as even less hypocritical because of their general positive affective tone. In line with the trait-congruence hypothesis (Rusting, 1999), extraverted people will interpret inconsistent CSR information in a more positive light per se. Initial research linking personality factors and CSR information shows that extraverted individuals are less skeptical of an organization’s CSR (Moscato & Hopp, 2019). Furthermore, they tend to “believe that firms can and do engage in CSR behaviors based upon their moral, ethical, and societal ideals” (Moscato & Hopp, 2019, p. 33). However, if individuals with a symbolized moral identity rate low on extraversion, the general effect of extraversion on favorable information judgment may be negligible.

Hypothesis 5a (H5a)

Extraversion moderates the interaction between CSR information and symbolized moral identity such that the stronger an individual’s symbolized moral identity and the more extraverted the individual, the less the difference in the perception of corporate hypocrisy of organizations associated with inconsistent CSR information versus organizations with consistent CSR information.

In turn, highly neurotic people who have a symbolized moral identity may perceive an organization as more hypocritical than less neurotic people. We expect that for those people, their tendency to make more negative judgments will make them perceive an organization as more hypocritical compared to those low on neuroticism. Indeed, people high in neuroticism judge organizational CSR more negatively: they are skeptical of CSR and do not believe there is a true ethical stance behind company CSR efforts (Moscato & Hopp, 2019).

Hypothesis 5b (H5b)

Neuroticism moderates the interaction between CSR information and symbolized moral identity such that the stronger an individual’s symbolized moral identity and the less neurotic the individual, the less the difference in the perception of corporate hypocrisy of organizations associated with inconsistent CSR information versus organizations with consistent CSR information.

Method

We tested our model using three studies (see Fig. 1). In Study 1, we investigated the relation between symbolized moral identity and perceived corporate hypocrisy (H1). In Study 2, using a longitudinal design, we assessed the sequential mediation model (H2). In both studies, we used inconsistent CSR information to induce corporate hypocrisy perceptions. In Study 3, using a longitudinal, experimental design we tested the interaction between CSR information and symbolized moral identity and the three-way interaction with extraversion and neuroticism, respectively (H3, H4, H5). We thereby randomly assigned participants to the condition of CSR-consistent and CSR-inconsistent information.

In all studies, we accounted for the different combinations of the two moral identity dimensions. First, in our main analysis, to assess an individual’s symbolized moral identity we used a subtractive difference score (symbolization—internalization). Researchers have used subtractive difference scores, for instance, in greenwashing contexts (Walker & Wan, 2012) or to assess discrepancies in internal and external CSR (Scheidler et al., 2019). For our symbolized moral identity score, greater positive values indicate stronger levels of a symbolized moral identity. Negative values indicate that internalization exceeds symbolization, which we hereafter label an internalized moral identity. If the two dimensions are balanced, the difference score takes a value of ‘0.’ Second, we tested three alternative models (AM). In AM 1, we combined the symbolization and internalization dimensions into an overall moral identity measure to account for the influence of individuals’ general moral identity. In AM 2, we tested the relative influence of symbolization while controlling for internalization. In AM 3, we tested the relative influence of internalization while controlling for symbolization. With AM 2 and 3, we aimed to clarify the role of each dimension in terms of reacting to inconsistent CSR information. Furthermore, we checked the robustness of our findings by analyzing our hypotheses with alternative methodological approaches.

As a post hoc analysis, we accounted for combinations of extraversion, neuroticism, symbolized moral identity, and (in)consistent CSR information by running additional regression analyses, including all the possible two- and three-way interaction terms and a four-way interaction term.

We recruited study participants via Prolific Academic (www.prolific.ac), who received compensation for participating. Conducting our study through an online platform was considered suitable because participants tend to represent the general public (Ferrer et al., 2015). Also, individuals usually receive information about companies’ CSR practices online (e.g., through media statements or newsletters). Compared to other online platforms (e.g., MTurk), Prolific Academic participants tend to be more honest and more naïve regarding the research purpose (Peer et al., 2017). Prolific Academic has previously been used to recruit participants for studies on individuals’ moral identity (Peterson Gloor, 2021). We targeted US citizens. Each study was conducted with non-overlapping samples.

Study 1

The aim of Study 1 was to test our main assumption; i.e., whether an individual’s symbolized moral identity is negatively associated with perceived corporate hypocrisy (H1).

Sample and Procedure

A total of 243 participants were recruited via Prolific Academic. We asked participants to engage in a task related to evaluating business practices. They were presented with a fictitious company and to read CSR-related information about the company. We used the vignette related to inconsistent CSR information developed by Wagner et al. (2009). We focused on a positive environment-related CSR company statement, followed by a piece of negative environment-related CSR media communication. We slightly modified the information in the negative CSR media communication. We stated that an NGO had accused the company of engaging in irresponsible behavior to make the inconsistent information less obvious (see Appendix 1). Furthermore, participants were informed that an NGO had collected signatures for a petition to enforce an official investigation into the company’s business practices. Last, respondents answered items related to perceived corporate hypocrisy, symbolization, internalization and the control variables. Participants were 41.2% female and 58.8% male. Four participants were non-binary or did not want to disclose their gender, and one person did not answer this question. For the analysis, we only included people that indicated their gender as female or male so we could interpret the data correctly. Hence, the final sample included 238 participants. Mean age was 32.65 (SD = 12.09) and 60.1% of the participants had obtained a college degree or higher.

Measures

If not stated otherwise, all items were measured on a five-point Likert scale.

Internalization and Symbolization

We measured internalization and symbolization using Aquino and Reed’s (2002) scales. Participants read about certain characteristics that may describe a moral person (e.g., caring, friendly) and thought about how such a person would feel and act. Subsequently, they answered questions related to internalization and symbolization. A sample item for internalization is: “It would make me feel good to be a person who has these characteristics.” A sample item for symbolization is: “I often wear clothes that identify me as having these characteristics.” The resulting scale for internalization (α = 0.83) and symbolization (α = 0.88) showed good internal consistency.

Symbolized Moral Identity (Symbolization—Internalization)

We measured symbolized moral identity using a subtractive difference score.

Perceived Corporate Hypocrisy

We measured perceived corporate hypocrisy with the six items developed by Wagner et al. (2009). A sample item is: “Power-Mart acts hypocritically” (α = 0.96).

Control Variables

We controlled for gender, as it affects perceived corporate hypocrisy (Scheidler et al., 2019). Also, we controlled for age, because older individuals award greater importance to CSR—it is in line with their life-stage goals (Wisse et al., 2018). We controlled for education since the participant’s text comprehension varies with educational background (Birkmire, 1985).

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

Table 1 summarizes the descriptive statistics and correlations.

Hypothesis Testing

The results of the regression analysis are presented in Table 2. The overall model was significant (F = 6.33, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.10). A symbolized moral identity was significantly and negatively associated with perceived corporate hypocrisy (b = − 0.17, p < 0.01), supporting H1.

Tables B1 and B2 in the online Appendix B present the three AM. Results indicated that the overall moral identity measure was not significantly related to perceived corporate hypocrisy (b = 0.06), while symbolization displayed a marginally significant and negative (b = − 0.12, p < 0.10), and internalization a significant and positive (b = 0.32, p < 0.01) association with perceived corporate hypocrisy.

Common Method Bias

We controlled for common method bias (CMV) using Harman’s one-factor test (Podsakoff et al., 2003). The single factor explained 32.62% of the variance, which is less than the suggested cutoff of 50% (Podsakoff et al., 2003).

Robustness Checks

We conducted three robustness checks (see online Appendix C). First, we ran a polynomial regression with response surface analysis. We did so to account for the potential drawbacks of using subtractive difference scores (see Edwards, 2001) for our symbolized moral identity measure (see Tables C1 and C2, Figure C1). We followed the steps recommended by Shanock et al. (2010). There is a negative significant slope along the line of incongruence but a non-significant curvature. This indicates that perceived corporate hypocrisy was less when the discrepancy was such that symbolization exceeded internalization, and the degree of discrepancy did not matter (see Notes in Table C2 for a more detailed interpretation of the polynomial regression results). Second, we categorized the participants into two groups: those with a symbolized moral identity and those with a balanced or internalized moral identity. We grouped participants into the symbolized moral identity group when their standardized symbolization measure was at least 0.5 times greater than their internalization measure (coded ‘1’). Otherwise, they were categorized as ‘0’. This procedure aligns with the classification described in online Appendix C for the polynomial regression analysis. Then, we ran a regression analysis (see Table C3). We ran a univariate analysis of variance as a third robustness check (see Table C4). The three robustness checks provide additional support for H1.

Discussion Study 1

The results of Study 1 show that the stronger an individual’s symbolized moral identity, the weaker the perceived corporate hypocrisy in response to inconsistent CSR information, supporting H1. Furthermore, results from testing the two moral identity dimensions separately point in a similar direction and confirm our assumptions: symbolization relates negatively, and internalization relates positively to perceived corporate hypocrisy. In addition, the association between the overall moral identity measure and perceived corporate hypocrisy was not significant. This finding highlights that using an overall measure for moral identity provides an incomplete picture of the role of moral identity in shaping reactions to inconsistent CSR information. Our robustness checks further strengthen our findings. The polynomial regression highlights that the direction of the discrepancy between the two dimensions matters regarding perceived corporate hypocrisy. Furthermore, categorizing individuals into either the symbolized moral identity group or the balanced/internalized moral identity group generates similar results. That is, our theorizing holds when using different methodological approaches to measure our construct of symbolized moral identity.

Study 2

The main aim of Study 2 was to test the entire mediation path from symbolized moral identity to willingness to engage in constructive punitive action via perceived corporate hypocrisy and feelings of anger. To increase the validity of our findings from Study 1, we used a longitudinal design in Study 2. Even though moral identity is an individual predisposition and is not likely to vary significantly across time, the cross-sectional approach of Study 1 is a limitation. Hence, in Study 2, we assessed the independent and the dependent variables with a seven-day time lag. We also controlled for the risk of a social desirability bias.

Sample and Procedure

A total of 310 participants were recruited via Prolific Academic. First, we assessed the independent variables and the control variables. Seven days later, we assessed the mediators and the dependent variables. We used the same vignette for the corporate hypocrisy manipulation as in Study 1. Of the initial participants, 248 completed both parts of the study. We identified one person that had participated twice. We chose to still include that person in the analysis and only kept the answers that were entered in the first round of participation. Furthermore, we used attention-check questions. Eleven participants failed to answer them correctly and were excluded from the analysis. Participants were 53.2% female, 44.3% male, 2.1% non-binary (n = 5), and one person did not provide information about the gender. As in Study 1, given the small number of participants not identifying as either male or female, we excluded these participants from our analysis. Furthermore, one person did not provide information about their age. Overall, our final sample included 230 participants. The mean age was 35.16 (SD = 11.66) and 58.7% of the participants had obtained a college degree or higher.

Measures

We measured internalization (α = 0.77), symbolization (α = 0.85), the symbolized moral identity measure, and perceived corporate hypocrisy (α = 0.94), as in Study 1.

Anger

We measured anger with the validated scale used by Joireman et al. (2013). We asked respondents how the information they read made them feel. A sample item is ‘outraged’ (α = 0.93).

Willingness to Engage in Constructive Punitive Action

We measured this variable by asking the individual: “How likely would you be signing the petition??” The petition was announced by the NGO that accused the company of having irresponsible business practices (see Appendix1). Prior to the question above, we added the following sentence: “Although it is not proven yet if the pollution is caused by Power-Mart, the NGO collects signatures for a petition to enforce an official investigation about Power-Mart’s business practices.” Research suggests that signing petitions can help challenge companies’ questionable behavior and urge companies to change their behavior (Minocher, 2019).

Control Variables

As in Study 1, we controlled for age, gender, and education. Additionally, we controlled for emotion regulation because an individual’s emotion regulation abilities may play a key role in responding to situations in which harm is done to others (Rivers et al., 2007). Furthermore, asking about one’s moral identity may induce social desirability bias (Shao et al., 2008). Therefore, we controlled for social desirability bias using Strahan and Gerbasi’s scale (1972). Each item was rated as true (= 1) or false (= 2). After reverse coding the first five items, the responses were summed up so that scores ranged from 10 to 20. Higher values indicated greater social desirability bias.

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

Table 3 summarizes the descriptive statistics and correlations.

Hypothesis Testing

We examined the sequential mediation with Hayes’ PROCESS macro (Hayes, 2017). We used the bootstrapping approach implemented in the macro with 5,000 bootstrapping resamples. Table 4 presents the results for H1 and H2. The model for the direct association between symbolized moral identity and perceived corporate hypocrisy was significant (F = 4.18, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.10). Symbolized moral identity was significantly and negatively associated with perceived corporate hypocrisy (b = − 0.22, p < 0.01), supporting H1.

Regarding H2, results of the sequential mediation analysis indicated an indirect, significantly negative association between symbolized moral identity and willingness to engage in constructive punitive action through perceived corporate hypocrisy and anger (b = − 0.05, CI [− 0.10; − 0.01]), supporting H2.

The results of the AM are similar to those of Study 1 (see Tables B3 and B4 in the online Appendix B): the overall moral identity measure was not significantly associated with perceived corporate hypocrisy (b = − 0.11). Symbolization had a significant and negative (b = − 0.22, p < 0.01) and internalization a significant and positive (b = 0.22, p < 0.05) association with perceived corporate hypocrisy. The indirect association with willingness to engage in constructive punitive action was significant for symbolization [b = −0.05, CI (− 0.11; − 0.01)] and internalization [b = 0.05, CI (0.001; 0.12)], but not for overall moral identity (b = − 0.03).

Common Method and Social Desirability Bias

The single factor explained 31.19% of the variance, which is acceptable (Podsakoff et al., 2003). Also, our predictions hold when controlling for social desirability bias.

Robustness Checks

We ran the same robustness checks for H1 as in Study 1, which point in a similar direction (see Tables C5-C8, Figure C2 in the online Appendix C). There is a significantly negative slope along the line of incongruence. In contrast to Study 1, we additionally found a significantly negative curvature. These findings indicate that although the degree of discrepancy mattered to a certain extent, the direction of discrepancy was still important (see Notes in Table C6 for a more detailed interpretation of the polynomial regression results). We checked the robustness of our findings regarding H2 in two ways. First, we re-ran the mediation analysis using the moral identity dummy (see Table C7). Second, we conducted path analysis, a structural equation modeling approach with manifest variables (MacCallum & Austin, 2000), to test the mediation effect using our original symbolized moral identity measure (see Table C9, Figure C3). The results confirmed our predictions.

Discussion Study 2

In Study 2, we find additional support for the negative association between a symbolized moral identity and perceptions of corporate hypocrisy, and thus, for H1. Study 2 extends Study 1 by finding support for H2, which suggests that perceptions of corporate hypocrisy and subsequent feelings of anger mediate the relation between a symbolized moral identity and willingness to engage in constructive punitive action. That is, a symbolized moral identity is negatively related to perceived corporate hypocrisy in response to inconsistent CSR information, which relates to weaker feelings of anger and less willingness to engage in constructive punitive action. The results of our AM show that individuals’ overall moral identity did not significantly influence their corporate hypocrisy perceptions. Furthermore, our robustness checks for H1 and H2 further supported our predictions.

Study 3

The aim of Study 3 was twofold: First, we wanted to rule out whether individuals with a symbolized moral identity are generally less skeptical, and test if the context matters. To do this we applied a between-subject (consistent vs. inconsistent CSR information) experimental design. As in Study 2, we collected data at two points in time. The second purpose was to test the moderating influence of extraversion and neuroticism while controlling for general personality traits.

Sample and Procedure

A total of 353 participants were recruited via Prolific Academic. We first assessed the independent variables, the two personality traits neuroticism and extraversion, and the control variables, and, seven days later, the mediators and the dependent variables. In this second part, we randomly assigned the participants to either the consistent CSR information scenario (consistently positive) or the inconsistent CSR information scenario. We used the vignette developed by Wagner et al. (2009). For the consistent CSR information scenario, we presented the participants with the positive environment-related CSR company statement as in Study 1 and 2, followed by a piece of positive environment-related CSR media communication. For the inconsistent CSR information scenario, we used the same vignette as in Study 1 and 2. Furthermore, we informed participants that an NGO was collecting signatures for a petition to enforce an official investigation into Power-Mart’s business practices. Last, the respondents answered items related to perceived corporate hypocrisy.

Of the 353 participants, 261 completed both parts of the study. We again used attention- check questions and had to exclude 12 participants who failed to answer the questions correctly. Participants were 72.7% female, and 26.5% male. Two participants were non-binary or did not want to disclose their gender and were excluded. Our final sample consisted of 247 participants. Participants had a mean age of 34.16 (SD = 11.36) and 61.1% of the participants had obtained a college degree or higher.

Measures

We measured internalization (α = 0.83), symbolization (α = 0.84), the symbolized moral identity measure, perceived corporate hypocrisy (α = 0.96), anger (α = 0.97), and willingness to sign a petition, as in Study 2.

CSR Information

We manipulated CSR information by randomly assigning participants to the consistent CSR information scenario or the inconsistent CSR information scenario. We measured CSR information (0 = consistent CSR information; 1 = inconsistent CSR information) as a dummy variable.

Willingness to Engage in Constructive Punitive Action

For the consistent CSR information scenario we used the same introductory sentence as in Study 2. In the consistent CSR information scenario we modified the sentence as follows: “Even though Power-Mart is considered an industry leader in protecting the natural environment, a local NGO has doubts about the sincerity of Power-Mart’s environmental engagement. Therefore, the NGO collects signatures for a petition to enforce an official investigation about Power-Mart’s business practices” (see Appendix 1).

Extraversion and Neuroticism

We used the short version of the big five personality traits questionnaire (BFI-10) (Rammstedt & John, 2007) to assess extraversion (α = 0.74) and neuroticism (α = 0.70) with two items. A sample item for extraversion is: “I see myself as someone who is outgoing, sociable.” A sample item for neuroticism is: “I see myself as someone who gets nervous easily.”

Control Variables

As in Study 2, we controlled for age, gender, education, emotion regulation, and social desirability bias. Furthermore, we controlled for the three additional personality traits of the Big5 measure: agreeableness, conscientiousness, and openness, using the BFI-10.

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

Table 5 summarizes the descriptive statistics and correlations.

Manipulation Check

We conducted a separate manipulation check for the consistent/inconsistent CSR information scenario that we adapted from Wagner et al. (2009) (see online Appendix D). We recruited participants via Prolific Academic and targeted US citizens. Participants (n = 61) were randomly assigned to either the consistent or inconsistent CSR information scenario. Then, we asked the following question as a manipulation check: The information about Power-Mart in the newsletter was consistent with information about Power-Mart in the local newspaper. By comparing mean differences, we found that the information about Power-Mart in the newsletter was perceived as significantly less consistent with the information about Power-Mart in the local newspaper in the inconsistent CRS information scenario (M = 1.19, SD = 0.10) compared to the consistent CSR information scenario (M = 4.63, SD = 0.11, p < 0.001), showing support for our manipulation.

Hypothesis Testing

First, we tested H3. As indicated in Table 6, the interaction between CSR communication and symbolized moral identity in relation to perceived corporate hypocrisy was significant (b = − 0.52, p < 0.001; R2 = 0.54).

Figure 3 shows that the slope was significant and positive for both those with a strong and a weak symbolized moral identity, while the slope was steeper for those with a weak symbolized moral identity (see Table 7 for the simple slopes). We further see that in the inconsistent CSR condition individuals with a weak symbolized moral identity perceived the organization as more hypocritical than those with a strong symbolized moral identity. These findings support H3.

H4 predicted that the positive relation between inconsistent CSR information and willingness to engage in constructive punitive action is weaker for individuals with a strong symbolized moral identity. The conditional indirect effect is significantly positive for a weak symbolized moral identity[b = 0.68, 95% CI (0.39, 1.01) ] and a strong symbolized moral identity [b = 0.39, 95% CI (0.21, 0.61)], while for a strong symbolized moral identity the association is less positive (see Table 8). The index of the moderated mediation was significant [b = − 0.18, 95% CI (− 0.32, − 0.07)]. The results support H4.

Next, we tested H5a, which predicted a three-way interaction between CSR information, symbolized moral identity, and extraversion in relation to perceived corporate hypocrisy. As indicated in Table 6, the three-way interaction term was significant (b = − 0.32, p < 0.05; R2 = 0.56). As shown in Fig. 4 and Table 7, individuals with a strong symbolized moral identity who rated high on extraversion perceive organizations as less hypocritical than those low on extraversion (see Table 7). This slope difference is marginally significant, showing initial support for H5a.

H5b predicted a three-way interaction between CSR information, symbolized moral identity, and neuroticism. The three-way interaction term was significant (b = 0.28, p < 0.05; R2 = 0.56) (see Table 6). Individuals with a strong symbolized moral identity who were low on neuroticism perceive the organization as significantly less hypocritical than those high on neuroticism (see Fig. 5 and Table 7), supporting H5b.

Regarding the AM (see Tables B5-B10 the online Appendix B), the two-way interaction between CSR information was marginally significant for the overall moral identity measure (b = − 0.32, p < 0.10), significant for the symbolization measure (b = − 0.42, p < 0.01), and non-significant for the internalization measure (b = 0.22). The three-way interaction with extraversion was significant for the internalization measure (b = 0.45, p < 0.05), and non-significant for the overall moral identity (b = 0.06) and the symbolization measure (b = − 0.14). The three-way interaction with neuroticism was significant for the symbolization measure (b = 0.29, p < 0.05) and the overall moral identity measure (b = 0.36, p < 0.05), and non-significant for the internalization measure (b = 0.12). The conditional indirect effects for overall moral identity, internalization, and symbolization were significant for low and high levels of the independent variable, respectively.

Common Method and Social Desirability Bias

The single factor explained 46.00% of the variance, which is acceptable (Podsakoff et al., 2003). Also, our predictions hold when controlling for social desirability bias.

Robustness Checks

We replicated our analysis by considering symbolized moral identity as a dummy. The results support H3, H4, H5a, and H5b (see Tables C10-C12 and Figures C4-C6 in the online Appendix C). Furthermore, the model of the path analysis showed a significant conditional indirect effect for different values of the moderator (see Table C13 and Figures C7 and C8). These findings further support our hypotheses.

Post hoc Analyses

In addition, we ran different combinations of two- and three-way interactions and a four-way interaction among CSR information, symbolized moral identity, extraversion, and neuroticism to account for the mutual influence of the variables. The different three-way interaction terms and the four-way interaction term were non-significant (see online Appendix E).

Discussion Study 3

Study 3 shows that CSR information and symbolized moral identity interact in predicting perceived corporate hypocrisy. First, the results show that individuals with a symbolized moral identity are not per se less critical of a company’s CSR. However, second, and in line with our findings in Study 1 and 2, the stronger an individual’s symbolized moral identity, the less pronounced the differences in corporate hypocrisy perceptions associated with cases of inconsistent CSR information and cases of consistent CSR information. Furthermore, we find a significant moderated mediation in terms of predicting willingness to sign a petition. This indicates, as in Study 2, that those individuals exposed to inconsistent CSR information become less angry and subsequently are less willing to sign a petition if they have a strong symbolized moral identity.

The results provide further insights regarding the role of individual predispositions in predicting perceived corporate hypocrisy. For those with a strong symbolized moral identity that rate highly on neuroticism, perceived corporate hypocrisy is higher than for those who rate low on neuroticism. Furthermore, we provide marginal support for the prediction that individuals with a strong symbolized moral identity who are also extraverted perceive an organization as even less hypocritical. Our robustness checks corroborate our assertions by showing that individuals who have a symbolized moral identity and are also extraverted perceive organizations as less hypocritical than those with a balanced/internalized moral identity. These findings suggest trait-congruent judgment effects when processing CSR information. Interestingly, different levels of extraversion and neuroticism do not make a difference for individuals with a weak symbolized moral identity.

The results of our AM show that the interaction between CSR information and overall moral identity is marginally significant, such that individuals with a weak overall moral identity perceive the organization as more hypocritical than those with a strong overall moral identity. All these insights suggest that considering an individual’s symbolized moral identity separately adds value, and that taking into account only the overall moral identity measure might lead to incomplete predictions. Our robustness checks further support our predictions.

Overall Discussion

In our studies, we examined the relation between an individual’s symbolized moral identity and their willingness to engage in constructive punitive action via perceived corporate hypocrisy and anger. Our results indicate that the higher an individual’s level of symbolization, the less likely they are to perceive corporations as acting hypocritically, which in turn lessens feelings of anger and reduces willingness to engage in constructive punitive action directed at corporations. The results also show that the more individuals internalize moral values, and the less they display their morality to the outside world, the more skeptical they are of organizations’ CSR efforts and the more willing they are to take action. Furthermore, our findings indicate that if individuals with a strong symbolized moral identity are also extraverted, perceived corporate hypocrisy is even weaker. In contrast, for neurotic individuals perceived corporate hypocrisy becomes stronger. These findings align with the trait-congruence hypothesis (Rusting, 1999), which suggests that extraversion and neuroticism unconsciously bias information judgment in a more positive or negative direction, respectively.

Theoretical Implications

This research contributes to the corporate hypocrisy and moral identity literature in important ways. First, we build on recent work that suggests that whether others’ inconsistencies are perceived as hypocritical is subjective (see Effron et al., 2018; Effron & Miller, 2015; Helgason & Effron, 2022; Lauriano et al., 2021) by focusing on individual predispositions in such contexts. Effron et al. (2018) suggest that individuals do not always attribute unearned moral benefit to others’ misalignment. Lauriano et al. (2021) further explain that some individuals may rationalize company misalignment, resulting in weaker hypocrisy perceptions. With our study, we provide additional insights into who these individuals may be. Individuals with high levels of symbolization may rationalize a misdeed because they are more tolerant of the occasional missteps of others (Kouchaki, 2011) and less likely to question the good intentions of others (Wiltermuth et al., 2010). For them, publicly talking about moral issues is an important part of who they are (Aquino & Reed, 2002). Furthermore, the results of our study suggest that extraversion and neuroticism amplify or weaken the influence of individuals’ moral identity in relation to evaluating companies’ word-deed misalignment.

In contrast, our findings show that individuals with high levels of internalization are more likely to perceive inconsistent CSR information as hypocritical firm behavior. We argue that this is because such misalignment contradicts how they view themselves. Related to this, Lauriano et al. (2021) find that when individuals “believe that [an] organisation knowingly makes insufficient effort to meet their targets and aspiration[s]” (Lauriano et al., 2021, p. 10), they perceive them as hypocritical. The results of our studies suggest that such individuals may have high levels of internalization, partly because of their sensitivity to morally laden behavior (Aquino et al., 2011) and others’ moral transgressions (Wiltermuth et al., 2010).

Second, we advance the corporate hypocrisy literature using CDT as a theoretical framework for explaining individuals’ reactions to inconsistent CSR information. Although the concept of cognitive dissonance has been considered an important element of corporate hypocrisy research (Wagner et al., 2009, 2019), the literature largely lacks explicit consideration of the cognitive dissonance process (Hinojosa et al., 2017) as an underlying framework that could explain how perceptions of corporate hypocrisy emerge and what the consequences are. Using the cognitive dissonance arousal and reduction process as a theoretical framework, we explain consequent affective reactions and behavioral intentions. More specifically, we show the relation to anger and constructive punitive action. While our findings indicate that these reactions are more likely to occur when organizations are perceived as acting hypocritically (and vice versa), these steps in the cognitive dissonance arousal and reduction processes might also be moderated by additional individual predispositions. We control for emotion regulation as this might influence affective reactions. Later research might build on these findings and the theoretical model to more explicitly investigate how individual predispositions influence reactions to perceived cognitive dissonance.

Third, we contribute to the moral identity literature (Aquino & Reed, 2002). In contrast to assumptions that individuals with a symbolized moral identity are more likely to engage in prosocial behavior as part of their public moral identity (Aquino & Reed, 2002; Winterich et al., 2013a, 2013b), our results indicate that such individuals are less likely to become angry and to retaliate when confronted with inconsistent CSR information. We argue that this is because of perceived familiarity with the respective organizations. Concurrently, our findings indicate that those with an internalized moral identity—i.e., those who strongly internalize moral values—are more likely to become active and sign a petition aimed at uncovering a company’s actual business practices. Interestingly, in general we do not find a relation between moral identity per se and corporate hypocrisy perceptions. Thus, it does not seem to be the individual’s overall moral identity that matters in such cases, but the intrapersonal imbalance between the two moral identity dimensions. Future research on moral identity could investigate the implications of these imbalances in relation to other morally laden situations.

Practical Implications

Our study has practical implications. First, it suggests that individual predispositions play a central role in individuals’ evaluations of organizations. In particular, we highlight that the extent to which individuals identify with a company is crucial: A mismatch between company and individual identity can create negative reactions, both in terms of emotions and subsequent behaviors. The more similar an organization is to its individual stakeholders, the more tolerant the latter are towards potential inconsistencies with CSR. Furthermore, we show that the personality traits of extraversion and neuroticism unconsciously bias individuals in their judgments of CSR information. Individuals may perceive information regarding CSR more positively or negatively per se. Therefore, importantly, companies should first try their best to avoid any misalignment. Organizations can do this by framing their CSR communication accordingly. Our results indicate that an internalized moral identity and neuroticism are related to increased skepticism. To alleviate some of the concerns of people who rate high on these aspects, companies might want to minimize the ambiguities in their CSR communication. For instance, the latter may report explicitly what they have done regarding CSR and provide proof of CSR commitments. Furthermore, trait-congruence judgment is particularly likely to occur if the information is emotionally laden (Rusting, 1999). Therefore, an emotionally neutral communication style may buffer trait-congruent judgments.

Second, our findings also have implications for how companies may want to interact and work with different stakeholders. Specifically, stakeholders are humans and have their individual predispositions that also become apparent in day-to-day interactions with businesses. Therefore, it is crucial to know who the individuals are with whom one is working, what matters to them, and what they value (e.g., what does the typical customer of the company look like, and what do they value?). This knowledge can enable companies to find effective ways to successfully interact and communicate with their individual stakeholders and minimize experiences of cognitive dissonance.

Third, our results reinforce the assumption that perceptions of corporate hypocrisy have implications for companies. Hypocrisy perceptions may trigger negative moral emotions and can make individuals want to do something about it, too. From a societal perspective, considering—for instance—the Decade of Action proclaimed by the United Nations (2021) and the strong push to create a more sustainable future by many societies, individuals with an internalized moral identity might be relevant actors as their moral outrage might push companies to further reflect on their inconsistent practices and ideally change their behavior and practice more substantive CSR.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

Our studies are not without limitations that suggest opportunities for future research. First, although we collected information about the independent and dependent variables at different times in Study 2 and 3, experimentally manipulated CSR information in Study 3, controlled for social desirability bias, and tested for CMV, we cannot fully rule out common method problems. The replication of our findings across different studies with different set-ups and different combinations of variables increases confidence in our findings. Nonetheless we welcome attempts to replicate the study results using alternative study designs.

Second, we used written vignettes to induce corporate hypocrisy perceptions. This is the predominant practice in the literature. In our case, we believe that a vignette study was fit for purpose because our population—the general public—generally receive company information through similar means (e.g., newsletters or media statements) and nowadays, often online. Alternatively, a video vignette could engage participants’ senses more holistically (Aguinis & Bradley, 2014). We encourage future attempts to replicate our findings using actual cases of inconsistent CSR information.

Third, we focused on one form of inconsistent CSR information. Our findings provide valuable insights into the individual differences in perceiving such information by highlighting the importance of individuals’ moral identity. However, it would be relevant to investigate further how individuals with a symbolized moral identity react to different forms of inconsistent CSR information and to information that prevails over a longer time. As Christensen et al., (2020) suggest, there are temporal modes of hypocrisy that range from aspiration to re-narration. Investigating how individuals react to such inconsistencies may be an important goal of later research. Furthermore, we focused on an environmental issue in our CSR information scenario. Investigating other CSR contexts (e.g., social aspects) might be interesting for future research.

Fourth, the main argument in our study is that individuals evaluate organizations in relation to how they view themselves. Furthermore, we expected that anger would be a common reaction in the context of inconsistent CSR information because observers often attribute responsibility to organizations (Kim et al., 2021), cannot control the situation (Watson & Spence, 2007), and perceive such scenarios as morally wrong (Wagner et al., 2009). Future research would benefit from measuring these underlying mechanisms and processes directly to provide more detailed insight into our results.

Last, we considered how individual predispositions shape perceptions of corporate hypocrisy but neglected to do so in relation to the subsequent cognitive dissonance arousal and reduction process. We deem such an approach appropriate because the basic premise of CDT (Festinger, 1957) is that individuals seek consonance between cognitions, so if the latter conflict, they aim at resolving them. However, we also acknowledge that how individuals respond to cognitive discrepancy may vary from individual to individual and requires case-by-case analysis. Hence, research is still needed to account for the subjectivity involved in the cognitive dissonance arousal and reduction process.

Conclusion

Findings from three studies show that individuals’ symbolized moral identity is negatively related to their willingness to engage in constructive punitive action in response to inconsistent CSR information via reducing perceived corporate hypocrisy and weakening feelings of anger. The results suggest that the more similar an organization is to its individual stakeholders, the more tolerant such stakeholders are towards potential inconsistencies in CSR. This tolerance may be greater for extraverted but not for neurotic people. However, a mismatch between organization’s and the individual’s identity may not always be a disadvantage. From a societal perspective, our findings suggest that individuals who internalize what they show to the outside world might be relevant actors in terms of challenging organizations and pushing them to engage in more consistent CSR behavior.

References

Aguinis, H., & Bradley, K. J. (2014). Best practice recommendations for designing and implementing experimental vignette methodology studies. Organizational Research Methods, 17(4), 351–371.

Aquino, K., Freeman, D., Reed, A., Lim, V. K. G., & Felps, W. (2009). Testing a social-cognitive model of moral behavior: The interactive influence of situations and moral identity centrality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 97(1), 123–141.

Aquino, K., McFerran, B., & Laven, M. (2011). Moral identity and the experience of moral elevation in response to acts of uncommon goodness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 100(4), 703–718.

Aquino, K., & Reed, A. (2002). The self-importance of moral identity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83(6), 1423–1440.

Aronson, E., Fried, C., & Stone, J. (1991). Overcoming denial and increasing the intention to use condoms through the induction of hypocrisy. American Journal of Public Health, 81, 1636–1638.

Averill, J. R. (1983). Studies on anger and aggression: Implications for theories of emotion. American Psychologist, 38(11), 1145–1160.

Babu, N., De Roeck, K., & Raineri, N. (2020). Hypocritical organizations: Implications for employee social responsibility. Journal of Business Research, 114, 376–384.

Barclay, L. J., Whiteside, D. B., & Aquino, K. (2014). To avenge or not to avenge? Exploring the interactive effects of moral identity and the negative reciprocity norm. Journal of Business Ethics, 121(1), 15–28.

Bartikowski, B., & Berens, G. (2021). Attribute framing in CSR communication: Doing good and spreading the word—but how? Journal of Business Research, 131, 700–708.

Batson, C. D., & Kennedy, C. L. (2007). Anger at unfairness: Is it moral outrage? European Journal of Social Psychology, 37, 1272–1285.

Birkmire, D. P. (1985). Text processing: The influence of text structure, background knowledge, and purpose. Reading Research Quarterly, 20(3), 314–326.

Bower, G. H. (1981). Mood and memory. American Psychologist, 36(2), 129–148.

Cheek, J. M., & Briggs, S. R. (1982). Self-consciousness and aspects of identity. Journal of Research in Personality, 16(4), 401–408.

Chen, Z., Hang, H., Pavelin, S., & Porter, L. (2020). Corporate social (ir)responsibility and corporate hypocrisy: Warmth, motive, and the protective value of corporate social responsibility. Business Ethics Quarterly, 30(4), 486–524.

Christensen, L. T., Morsing, M., & Thyssen, O. (2020). Timely hypocrisy? Hypocrisy temporalities in CSR communication. Journal of Business Research, 114, 327–335.

Clouse, M., Giacalone, R. A., Olsen, T. D., & Patelli, L. (2017). Individual ethical orientations and the perceived acceptability of questionable finance ethics decisions. Journal of Business Ethics, 144(3), 549–558.