Abstract

This study examines local communities’ lived experiences and organizations’ care-giving processes regarding four oil and gas projects deployed in three countries. Analyzing the empirical data through the lens of ethics of care reveals that, together with mature justice, the inclination to care conceived at the focal organization creates an ethical culture encouraging caring activities by individuals at the local level. Through close communications with communities, project decision makers at the local level recognize the demanded care of local communities and develop organizations’ caring capacity. The empirical analysis revealed that the care-giving process can also be influenced by the power dynamics of the network of stakeholders. This research emphasizes on the success of a bottom-up approach in caring for local communities, and sheds light on the capability of large organizations in giving care to their distal stakeholders by adopting this approach. Furthermore, it indicates that justice and care both have some useful characteristics and are complementary but, most importantly, are socially constructed and not mutually exclusive.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The emergence of community inclusiveness practices in oil and gas projects deployed in developing countries is a relatively new phenomenon (Idemudia 2007). Nevertheless, over a short period, these activities have been firmly established in project organizations in this sector, arguably transforming these organizations into the champions of community responsive behavior (Wheeler et al. 2002; Frynas 2005, 2010). The influence of these practices, however, is not completely mirrored in communities’ satisfaction trends (Frynas 2010). In some parts of the world, project unpopularity, community protests, and resistance against organizations are surprisingly increasing in terms of intensity and scale (Boholm 1998; Dear 1992; Lake 1993; Idemudia and Ite 2006; Hanna et al. 2016; Teo and Loosemore 2017).

The problems involved in the interrelation of communities and organizations have been explored by many researchers in the field (see, for example, Maranville 1989; Brammer and Millington 2003; Hart and Sharma 2004; Jamali 2008, Tang-Lee 2016). Nevertheless, it is believed that there are two major interrelated shortfalls in the mainstream research on stakeholders, due to which the literature has failed to provide a comprehensive image of the debate.

First, the majority of previous investigations have revolved around examining the fiduciary duty of an organization (e.g., Hanly 1992; Richardson 2009), developing corporate social responsibility plans (e.g., Sacconi 2006; Slack 2012), and studying the influence of community development practices on an organization’s viability (e.g., Brammer and Millington 2003; Van Der Voort et al. 2009), and thus have been related to strategy and business ethics. This organization-centric approach (Friedman and Miles 2006), adopted in the vast majority of stakeholder research, has resulted in the representation of stakeholder relationships as dyadic and independent (Frooman 1999), with an “unbalanced perspective in which the stakeholder voice is underrepresented and remains a limitation of stakeholder theory” (Miles 2017, p. 448).

Second, at the ontological level, stakeholder theory “is underpinned by an implicit, and problematic assumption of essentialist self” (Bondy and Charles 2018), in which an organization is treated as an autonomous focal self that is “isolatable from other selves and from its larger context” (Wicks et al. 1994, p. 479). In the theoretical realm, the consequences of this assumption are that an organization is considered an independent decision maker, and managers are considered the balance keepers of stakeholders’ interests (Freeman et al. 2010; Reynolds et al. 2006); thus, the stakeholders are forced into an inactive position and separated from the decisions that influence them most (Derakhshan et al. 2019a). From a practical perspective, this approach has resulted in marginalizing the least powerful and vocal stakeholders, such as local communities (Bondy and Charles 2018; Derry 2012), and providing “undemocratic” development programs (Banerjee 2008) that are “nonnegotiable” by local communities (Blowfield 2005).

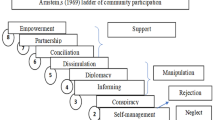

These theoretical and practical approaches to conceptualizing stakeholders describe a set of characteristics that are historically embodied by men. It can be argued that the masculinist assumptions of stakeholder theory extend to influencing how local communities are treated by both oil companies and stakeholder scholars, who place a premium on the autonomy, power, and independent nature of organizations and who routinely marginalize less powerful local communities (Fig 2007).

A stream of research was started in early 1990s in business ethics literature, claiming to articulate a feminist stakeholder theory with the earnest application of feminist perspectives in stakeholder studies in the seminal work of Wicks et al. (1994, p. 483), who questioned masculinist assumptions of stakeholder theory suggesting that “the individual and the community, the self and the other are two sides of the same coin and must be understood in terms of each other.” Following the same path, Burton and Dunn (1996) stipulated that the moral grounding of stakeholder theory cannot be competition and justice but must be cooperation and caring; thus, they emphasized the application of the ethics of caring proposed by Gilligan (1982) in stakeholder research (Grosser et al., 2017).

Gilligan (1982) raised the point that the traditional moral values of justice are mostly linked to men’s traits, while women’s moral approach is characterized by caring about oneself and others. This stereotyping, based on presumed gender differences, was later criticized by feminist theorists, such as Tong (1995), Derry (1996), and Kelan (2008), for exacerbating gender inequality and ignoring individual capabilities rather than representing a more emancipatory approach, which does not reinforce feminine stereotypes but challenges them instead. Established over these critiques, I argue that while many of the assertions and suggestions about the value of care-based reasoning are valuable and worth building on, these are no longer considered feminist theories. Therefore, in this research, I will draw on this stream of business ethics literature, but I will refer to them as care-giving approaches rather than feminist approaches as I believe that a careful consideration of care-giving is a worthwhile component of ethical reasoning and conduct.

Care-giving has been identified as the moral grounding of stakeholder theory (Burton and Dunn 1996). Despite its potential, the translation of ethics of care into organizations’ practices, particularly its influence on stakeholders’ satisfaction, have both remained overlooked (Jensen and Sandström 2013). There is an enormous gap in our understanding of the actualities of organizations participating in care-giving processes—a gap that can only be filled with narratives that flesh out our conceptual understanding of the care-giving behavior of organizations and help organizations to understand how to develop these traits (Wicks 1996).

Against this background, in this article, I study the lived experiences of four oil and gas projects deployed in three developing countries. My initial aim was to apply stakeholder theory in order to explore the influence of organizations’ behavior on local communities’ perception from the community development projects. However, my empirical observations from two organizations with very different behavior toward local communities revealed that local communities’ viewpoints cannot be directly linked to the stakeholder orientations of organizations. This led me to seek new insights from empirical data through the lens of ethics of care and ethics of justice. Therefore, I investigated the viewpoints of local communities and the project operating organizations to understand how these organizations embody a care-giving approach toward the communities and how this approach influences the organization’s relationships with local communities and the fulfillment of their responsibilities toward them.

In the remainder of this article, I review the relevant literature and explain the methodology and process of data gathering and analysis. I then discuss the results from the case observations and eventually examine them using dimensions of ethics of care. This article concludes by emphasizing the theoretical contribution of the research in comparison to the constructs and nomological relationships existing in the literature.

Justice and Care

Ethics of justice has been elaborated by several researchers to articulate a model of moral reasoning (Simola 2003). The most prominent theory of moral reasoning, established over justice, is developed by Kohlberg (1974, 1981). According to Kohlber’s model, in order to apply justice in moral reasoning, the ability to think in the abstract must be developed. That is, the decision maker must abstract features of particular situations that are consistent with more general universal principles. Furthermore, Kohlberg introduced three levels of maturity in embodying justice. While in its most immature level of justice the moral constructs reflect individual’s needs, in the second level, the fairness in decision making is grounded over a shared understanding of societal norms and values, and finally, the most matured level of justice follows certain universal principles (Simola 2003).

It can be argued that an ethics of justice constitutes a perspective toward fairness that is demonstrated through reciprocity; where using formal logics (i.e., universal principles and rules) the rights of individuals are protected and fulfilled (Kohlberg 1974). In the reasoning of the ethics of justice, drawn from the work of Immanuel Kant and his intellectual heirs, the focus is on absolute standards of rights and duties, regardless of the complexity of particular relationships or the subjectivity of experiences (Botes 2000; Simola 2003; Machold et al. 2008).

Ethics of care, on the other hand, constitutes an ethical approach in which involvement, relationships, and the needs of others play an important part in ethical decision making. Dimensions and values of ethics of care have been introduced by many authors such as Noddings (1984, p. 2) who described caring as “rooted in receptivity, relatedness and responsiveness.” After Gilligan’s (1982) pioneering work, many subsequent researchers distinguished among ethics of justice and ethics of care; thus, they departed from the legalistic and contractual nature of Kantian ethics and built arguments on following responsibilities through giving care (Burton and Dunn 1996; Held 2006; Liedtka 1996; Tronto 1993). This distinction originated from the ontological and epistemological differences between the two approaches, as explained below.

Ontology of the Organization: Autonomy and Interdependence

In the post-Enlightenment West, individuals are defined as autonomous agents who are fundamentally independent from others (Wicks et al. 1994), and this autonomy has been introduced as the basis for the ethical actions of agents (Bowie 1998; Borgerson 2007). Consequently, relationships are considered threats to the moral integrity of the autonomous self since they can impose new roles on moral agents and curb their freedom in decision making (Borgerson 2007). A moral organization can thus influence or be influenced by its stakeholders, but the stakeholders never become an integrated part of the organization, and the organization remains the prominent decision maker (Wicks et al. 1994).

The notion of the self-mentioned in ethics of care, in contrast, is largely interdependent and relational (Sevenhuijsen 2003a, b) since the “self” cannot be defined without “others,” and its existence cannot be separated from its relationships (Burton and Dunn 1996; Tong 1995). The definitions of “relational self” (Bondy and Charles 2018) and “relational autonomy” (Mackenzie and Stoljar 2000) are conceived in light of this ontological shift.

Wicks et al. (1994, p. 483) defined a care-giving organization that is “constituted by the network of relationships which is involved in with the employees, customers, suppliers, communities, businesses and other groups who interact with and give meaning and definition to the corporation.” In a similar vein, Bondy and Charles (2018, p. 76) introduced “a stakeholder concept enriched by an explicit use of relational self, where multiple dynamic selves are recognized as comprising the whole self, and selves held in common with others are found outside and inside the organization.” They sharply mobilized this notion to the next level by arguing that it is not only the individuals inside stakeholder groups who contribute to the heterogeneous composition of the groups; rather, each individual acquires several identities that, collected together, shape the individual’s holistic self, and thus contribute to the diversity of the group.

Responsibility: Duty and Care

Shifting the concept from the focal self to the self-embedded in a network of relationships invokes a notion of responsibility beyond the traditional contractual Kantian duties. Responsibility discussed through dimensions of care (Burton and Dunn 1996; Machold et al. 2008) indicates that this notion is socially constructed and co-defined by the care-giver and care receiver (Nicholson and Kurucz 2019). In order to better comprehend responsibility, we need to go through the different dimensions of care.

The first dimension of care stands for the recognition that there is a need for care, thus achieving attentiveness, as introduced by Sevenhuijsen (2003a, b) and Tronto (1993). The second dimension “is based on the willingness and capacity to take responsibility that ‘something’ is done to provide for the need in question.” (Sevenhuijsen 2003a, b, p. 184). Responsibility is a process and a practice, as opposed to an “abstract, one-off, moral dilemma” (Macholds et al. 2008, p. 671), given to all members of a network of relationships to consider their own goods and others’ goods (Nicholson and Kurucz 2019), and thus goes beyond the predefined roles and right approach in defining duties to self and others. Fulfilling responsibility through care-giving is a continuous social process and must be repeated to be mastered. The next dimension of care, empathy, focuses on carrying out the caring activities and ensuring that caring needs are met (Sevenhuijsen 2003a, b; Macholds et al. 2008). Within the same dimension of care, competence, as a value, corresponds with performing actual caring activities based on the competencies and resources of the care-giver. Finally, responsiveness focuses on the interaction between giver and recipient of care and is necessary to ensure that the given care is well received by its target (Noddings 1984).

Knowledge: Universal Hard Fact and Relativist Truth

In the socially constructed world described by pragmatists, the “truth” can have different versions narrated by different individuals (Rorty 1985). Accordingly, there are no hard facts by which an organization can establish the authenticity of its actions (Machold et al. 2008), but there are different interpretations of facts narrated by individuals based on their psychological, social, and cultural stances. Through their suggested fallibilistic stakeholder pragmatism, Jensen and Sandström (2013) established a link between an organization reaching a common decision shaped by different stakeholders and plural versions of the truth. Furthermore, the ethics of care argues that, while caring is the universal main component of an organization’s duty, it can be defined relatively and practiced according to the context of the relationships (Noddings 1984).

The ability to recognize the need to care contrasts with the rationalization of this need from the distance of the locus of the care-giver (Liedtka 1996). This ability refers to the willingness to place the self in a position to view the world through others’ perspectives and thus to grasp their perceptions and world (Machold et al. 2008). The reverse perspective, however, was rejected by Young (1997). Through her asymmetric reciprocity theory, she argued that, as humans, we are so contingent on the context of our relationship networks that we will never be able to see the world through someone else’s eyes. Nevertheless, what we should do as ethical agents is be open to the heterogeneity of the world and accept the plural unique subjectivity of the viewpoints of others with dignity and respect. This practice implies “careful and respectful listening and responding to the voice of those who are involved in the problem in question” (Sevenhuijsen 2003a, b, p. 187) and moving along the process of learning from the feelings, motives, and reactions of others in their respective contexts by engaging in dialogue with them (Borgerson 2007).

In ethics of care, the knowledge gained through relationships drives our decisions regarding right action: “we know particular things about particular humans, and because of this knowledge we are partial toward some of those humans” (Burton and Dunn 1996, p. 135). Caring about stakeholders, or having more knowledge about them, would extend the decisions to include not only stakeholders who have more power but also those who are more vulnerable to the risks.

Methodology

Research Design

This research entails studying four selected projects deployed in the oil and gas sector in three developing countries. For anonymity reasons, I cannot reveal the name of the country where the first two cases are located. The next two countries are Nigeria and Kazakhstan. All four cases describe local communities living in proximity to the selected oil and gas projects; these cases provide empirical evidence to better understand the behaviors of organizations with local communities. The case study approach is a research strategy aiming to understand the dynamics and underpinning processes of phenomena (Eisenhardt 1989) within their contingent local contexts (Miles and Huberman 1994) and is therefore appropriate for my purpose.

This research is abductive by nature, aligning the theoretical (deductive) and empirical (inductive) underpinning processes of research (Dubois and Gadde 2002). My initial aim was to explore how local communities perceive an organization’s development projects and how an organization’s behavior influences this perception. Therefore, I was looking for two oil companies with very different approaches to local communities, and stakeholder theory functioned as a general initial framework when the data collection started.

I used the theoretical replication to select the cases for multiple-case analysis (Yin 2013). The study of each case entails studying the organization’s stakeholder processes at both the organizational level and the local level. I deliberately selected two organizations with two extreme shareholder or stakeholder orientations: the multinational oil company (MNOC), with its headquarters in a European country, extensive community development programs, and substantial financial investments in community satisfaction designed at the organization level; and the national oil company (NOC), owned by the government and with almost no systematic development projects to appease the local communities.

In the next step, among several projects deployed by the two organizations, I searched for local communities with different levels of satisfaction. Local communities’ satisfaction cannot be simplified to be measured with determined criteria. To make this selection, I investigated the level of controversy of projects in mass media. This investigation resulted in the selection of two projects conducted by NOC: Case 1, which is located in a Special Zone known as one of the most controversial oil extraction projects in the country; and Case 2, which has much less community opposition.

Among different countries where the MNOC deploys extraction projects, Nigeria, and more specifically the Niger Delta, has historically been the focus of international concern regarding the clumsy behaviors of multinational oil companies (Idemudia 2007). Therefore, considering the same criterion of different levels of local communities’ satisfaction, and with the aim of exploring some of the most underrepresented communities, a village in one of the remotest areas of the Niger Delta and Aksay in Kazakhstan were selected as Case 3 and 4.

After initiating data gathering, I noticed that there is a massive gap between what informants from organizations express about their organizations’ activities regarding local communities, and how local communities perceive the influence of project and organization’s initiatives on their life. As I discovered, local communities’ viewpoints of organizations’ development projects could not be directly linked to the stakeholder orientations of organizations. In line with the nonmatching observations, parallel to the data collection, the search for theories reconciling this contradiction was ongoing (Dubois and Gadde 2002; Taylor et al. 2002). Eventually, this process led me to seek new insights from empirical data through the lens of the ethics of care. Since the cases evolved when more data were collected, the emergent empirical evidence contributed to the generation of new concepts extending the ethics of care in stakeholder realm.

Data Collection

To extract the essence of case study methodology, I used triangulation (Johansson 2007) in combining the methods and data sources (Mathison 1988). The primary data consist of 37 semi-structured interviews in total (Appendices 1 and 2), and direct field visits in Cases 1 and 2 to obtain a deeper understanding of the conditions of the cases and to conduct interviews with local communities. For the two latter cases, I investigated social media, searching for videos, news, tweets, and articles about the cases. I contacted many of the content producers and received responses from a few of them, with whom I conducted interviews. Community activists put me in contact with other members of the community. These informants preferred to receive a list of questions to answer by voice recording. I sent my interview questions to them, and in response, I received several voice recordings explaining the condition of their village and their relationships with the MNOC, in addition to some photos and one video. Additional sources of data included the organization’s documents, notes from field observations and several articles, and documentaries collected from media and social networks (Appendix 3).

Data Analysis

Relying on abductive reasoning, the data analysis entailed coding the interviews and the transcription of voice recordings with three sets of codes (Appendix 4). The additional sources of data were reviewed, and their relevant sections were extracted, coded, and used in the study for the identification of the responsibilities of organizations and their relationships with the local communities; the viewpoints, concerns, and demands of local communities; and the characterization of the project context.

The empirical realm of the research emerged with new variables influencing the observed phenomena. The list of inductive coding dimensions covered these context-contingent variables. The social and environmental conditions of the cases, such as communities’ power, rights, traditions, professions, and lifestyles, and the details of community processes at the local level are among the inductive coding dimensions.

Through a deductive process, I highlighted the roles and rights of local communities as defined by the organizations. I used the attentiveness dimension of the ethics of care to interpret the organizations’ approaches to their responsibilities. The processes underpinning the recognition of the demanded care of the local communities, in addition to the processes designed for performing caring activities, were analyzed. The questions regarding organizations’ interactions with local communities and their influence on the care-giving processes were interpreted through dimensions of ethics of care. To make sense of the findings about the distribution of power between organizations and local communities, the empirical data were analyzed according to the hierarchical or decentralized structure of the organization and the local level.

The third set of coding dimensions is analytical, highlighting the patterns and links between the constructs developed in the two presented coding processes. These codes can be grouped into the analysis of the ontology of the organization and its influence on the care-giving processes in the projects, the organization’s approach to empowering local communities, and the assessment of the influence of other stakeholders on the care given to local communities. Finally, this set of codes analyzes the behaviors and viewpoints of individuals from both the organization and local communities about the demanded care and the caring processes. The results of the three-step analysis consist of general and particular suggestions to support a conclusion (Kovács and Spens 2005).

Findings

Case 1

The project in Case 1 is part of a 28 phase, 460 km2 project, named a Special Economic Energy Zone (Special Zone from now on) and recognized as the most complex project of the country. The project is deployed to extract oil and gas from a reservoir shared with a neighboring country and is therefore of strategic political importance for the national government. The part of the project studied for this research is placed in the vicinity of a small village with a total population of less than 400 indigenous inhabitants and its construction was initiated approximately two decades ago. Communities’ traditional occupation is farming on the land and fishing from the nearby gulf. After long-term negotiations between the communities and NOC, the majority of their farming lands were purchased by NOC “with the prices decided by the NOC” (journalist), and the fishing harbor is completely occupied by offshore plants. Consequently, a majority of the communities have lost their traditional jobs, while only a few of them are employed in the project for low paid simple jobs.

This project has absorbed substantial skilled workforces from all around the country. These employees are mainly individual men who cannot afford living in the residential complexes developed by NOC for project managers and reside at the outskirts of the village, creating a sort of slum:

The population has grown fourfold over the last decade due to the employees’ settlement in the village. They live without their families, and this has engendered many social issues (council member).

The NOC is not involved in deployment of any community development projects in the whole Special Zone. Communities, however, are permitted to use the road, bridge, airport, and hospital built for the purposes of the project, knowing that the priority of usage must be given to the project.

Due to the transformative social, environmental, and financial impacts of the project on communities’ life, demonstrations, and oppositions against the project are quite common in the Special Zone. The demonstrations are usually covered by local media (newspapers and news websites of the Special Zone) and are extensively discussed by the two parliament members of the Special Zone. Their main focus, however, is on covering the issues of larger towns of the Special Zone. Accordingly, the NOC is more reactive to the issues that have emerged in those towns, and so the recruitment programs, disseminations of impact assessment reports, and discussions in the local journal articles are all targeting those larger more covered towns.

As a state-owned organization, NOC collaborates quite closely with the national government and consequently follows the government’s policies. The NOC’s firm belief suggests that, due to the strategic importance of the project, nothing should constrain the scope or aims of the project. The NOC has no direct relations with the local community individuals. Communities of each certain district of the country elect their council members who are responsible to manage the general affairs of their electoral district. The council members in Case 1 are not permitted by NOC to participate in the sessions held between the government and the organization authorities for making decisions about the communities since:

The issues consulted with government in these meetings are very sensitive and can lead to considerable social conflicts. No external body is allowed to participate in the decision making (program manager).

Although there are monthly meetings held between NOC representatives and council members at the local level, but they are described as formalities since:

The NOC representatives who participate in these meetings do not have any authority and their presence has no influence on addressing the needs of the local communities (council member).

The NOC’s policy suggests that the communities would automatically benefit from the financial welfare coming from the project, and their other concerns and demands are not worthy of consideration. Therefore, traces of immature justice, as described by the first level of Kohlberg’s (1974) model of moral development, can be observed in this policy:

Communities must be satisfied because their living conditions are much improved in general. They complain. I know it, but they should also be aware that the situation is the same all around the world. Industrial areas have environmental and social impacts. These issues have become a permanent part of their lives, but local communities are gaining benefits in return (project manager).

Axiomatically, this policy prevents pursuing the further steps of care-giving activities, and it hampers local communities’ protection from the negative impacts of the project. Moreover, many of the transformative impacts of the project on communities are justified by the strategic importance of the project without a minimum effort by the NOC to mitigate them.

The NOC’s extreme avoidance of relationships with local communities and its autonomy in defining the right and wrong and deciding for local communities according to its own perspective speaks to a considerable inclination toward immature justice-based moral reasoning. Furthermore, the analysis in this case indicates that the power asymmetry between the NOC and local communities is highly unbalanced, and harms to the local communities caused by the project intensified this asymmetry. Together with the government, the NOC forces the local communities to adapt to the project. The communities’ right to make decisions on the aspects that influence them the most is neglected, and the project has left them no other option than to abandon their jobs, sell their land, and start to earn money in ways that the new condition dictates that they do.

Case 2

The project studied for Case 2 is deployed by NOC but is located in another part of the country. This project entails of the construction of the largest refinery plant of the nation, located in 30 km distant of a town with a population of 100,000. In comparison to Case 1, the project in Case 2 is of less strategic importance for the government. Due to the nature of the jobs held by the local communities, their life is not drastically influenced by the project.

In comparison to Case 1, the town of Case 2 is relatively more developed and there has never been any request for NOC to be involved in development of infrastructures or facilities for the communities. The only infrastructure developed by NOC is an airport currently used by both project employees and local communities. On the other hand, due to the high unemployment rate, recruitment in the project has been the main request of local communities from the beginning. The NOC initially showed no interest in recruiting from the local communities. All the main contractors were from other parts of the country, bringing their workers with them. This uninvited mix of cultures had magnified the communities’ dissatisfaction and resulted in scattered protests and even collective violence in the town. They were abruptly suppressed by intrusion of military forces.

At the local level, there have never been any negotiations between local communities or council members and the project authorities:

We have invited the project manager to participate in council meetings many times, but he has never accepted our invitation (council member).

However, in Case 2, the council members are powerful enough to make their voices heard through the local and national media and even to lobby their legislature members. Consequently, through media and political lobbying, a change was enabled in the power dynamics between the local communities and the NOC as the communities’ needs were vocalized:

If there is one benefit coming from this project, it would be improving the financial status of the town. Local communities are suffering from unemployment, and by recruiting them in the project, the condition can be changed (local journal).

The NOC eventually decided to define some recruitment programs, accompanied by trainings, to hire from the local communities. Two years after the project start, the first call for hiring from local communities was announced on the NOC’s website and approximately 600 individuals from the local community were hired in the first intake of this recruitment scheme.

Case 3

The MNOC in Case 3 deploys a massive project covering more than 36 thousand km2 of Niger Delta. There are approximately 350 villages living among the plants and pipelines of the oil extraction facilities. For the purpose of this study, I approached one of the villages with a population of just over a hundred. Local communities in Niger Delta are highly dependent on the environment for farming and fishing. However, the agricultural lands are severely contaminated by oil spills. Drinking water is usually polluted, and a sheen of oil is visible in many localized bodies of water. Offshore spills have contaminated coastal environments and have resulted in a drop in local fishing production. The extraction project described in Case 3 as well as all of the Niger Delta is riddled with conflicts between local communities and multinational oil companies. Activists from villages are involved in vocalizing the demands of local communities. These activists mainly produce content in blogs and forums or participate in media parleys criticizing the careless approach of the multinational oil companies.

In contrast to NOC, the authorities at the MNOC’s headquarter expressed attentiveness regarding the responsibility of caring about the communities’ demands and concerns:

As an organization, we try to respect the cultural differences, and we try to benefit from the culture as richness to understand better what [local communities’] needs might be in terms of social projects (senior manager at community development department).

The need to care being recognized, the MNOC attempts to conduct caring activities in its projects. However, in Case 3, there are several issues incorporated by taking further steps.

A substantial part of the decisions about the local communities are made at the organization level in collaboration with the government that regulates what the MNOC should do for budget allocation:

There is a preagreement with the government before any decision is made. So there are some intentions from our side, and there are obligations from the government’s side. Then, we as a function try to understand local communities in deciding how to spend their budget, which has been allocated (senior manager at community development department).

In addition to the considerable influence of the government, the recognition of the demanded care of the local communities is mainly grounded in distal and inaccurate perceptions. In contrast to the NOC, the MNOC at the organization level shows willingness to establish close relationships with local communities and to address communities’ needs in all of its projects. Nonetheless, analysis from MNOC’s approach at the local level of Case 3 reveals that instead of active involvement of local communities in decision making, the main intention of these contacts is addressing communities’ complaints:

This is a formal process that, through day-by-day relations with local communities, we receive their complaints by every means, by phone, by writing, by just knocking on the door of our office (senior manager at community development department).

Managers at the MNOC’s headquarter explained that in all of their projects, the communities are communicated through their representatives. However, referring to the local communities revealed that in Case 3, the communities have no official representative for the young, women, and other vulnerable groups, and only important political families of the area who have very good connections with the MNOC and the government have regular meetings with the authorized bodies of MNOC in Niger Delta. Many of the individuals from the community have no direct contact with any decision maker from the MNOC since “no manager stayed in the village, not even for one night” (local community activist), and the project site visits by project authorities are limited to very quick inspections:

The local communities recognize the logo of [MNOC], but they do not personally know anyone from the project personnel (journalist).

Due to the rough conditions of the area, project personnel live separated from the local communities with conditions that are drastically different from the life in the village; thus, there is no receptiveness between the organization and the local communities:

[Project personnel] live in big compounds, where they just move in and out with their big cars. They live in nice houses and quite infrequently interact with the communities (journalist).

Due to the lack of communication with local communities at the local level, the MNOC at the organization level has developed a very homogeneous perception from the hundreds of indigenous tribes and thousands of individuals with different beliefs, concerns, and demands. The MNOC’s knowledge of communities’ demands is limited to a few sample Niger Delta communities studied in the past. The result is the design of very similar development projects in different locations within one country, as reflected in communities’ viewpoints:

The [MNOC] is doing very little to address the challenges of the local communities, and there is a big gap between the two … The [MNOC] has its own plans, which are quite different from the communities' cultures and lifestyles, even if they pretend that they are willing to fall in line (local community activist).

Moreover, despite the intention at the organization level to hold responsibility for addressing the communities’ needs, the capacities to provide the recognized care in accordance with the demand are not developed at the local level:

They are usually supposed to come up with the exact and right thing to do … But it is not their core business to conduct development projects, and you see that in the way they implement the projects. It is something straightforward, as their other business activities. It moves aside their core business (journalist).

Furthermore, the decisions made in collaboration with the government have an overemphasis on developing hard infrastructures since the Nigerian government wants such projects. Many of these infrastructures are mismanaged, and I was not able to find any concluded community development project conducted by the MNOC in the location of Case 3:

The cottage hospital of the village is abandoned since there were no medical personnel paid to work in there (local community activist).

Due to the substantial environmental degradation and inability to continue agricultural activities, local communities in Case 3 are financially dependent on the MNOC, and working for the MNOC is the only hope of employment for the local communities. Project authorities at the local level do not control the hiring within local communities. The powerful families of the area manage the whole supply chain of the workers. In the lack of systematic plans for developing local communities’ skills and nurturing their capacities, the work done by the young people of the community is occasional and does not require specialization. Moreover, the majority of these workers have no contract and can be redundant at any time.

The local communities are completely dependent on the MNOC for their living and perceive that “…oil brings richness, but this richness might not go to them” (Journalist). Therefore, they do not develop a positive perception of the project. The MNOC’s lack of capacity and competencies for performing caring activities has resulted in the perception of humiliation and disrespect among local communities:

No local community wants to abandon its culture and lifestyle for more money handed down by oil companies … by this, I mean there is much disrespect on the part of [the MNOC] to the locals (local community activist).

The empirical data in Case 3 point to very noticeable difference between the plans and aims decided at the organization level and the actualities at the local level. While the data from the organization level reveal the organization’s aim to care about local communities, the data collected from the local level elucidate that local community members do not perceive that MNOC is engaged in caring activities.. As a result, despite the evident difference at the organization level, the condition in Case 3 is quite similar to Case 1.

Case 4

The project in Case 4 is located over one of the four oil and gas reservoirs in Kazakhstan, 20 km distanced from the town of Aksay with a population of approximately 30 thousand, and nine villages with a total population of 5500. The MNOC has a 40-year agreement with the Kazakh government “to develop the field to allow the production to reach world markets, currently celebrating half way” (Project Manager).

The community development projects in Case 4 consist of a portfolio of multiple projects with the aim of “diversification of the local economy and sustainable social and economic growth” (community manager). The Kazakh government emphasizes the development of hard infrastructures, providing a list of their requests to the MNOC on agreement. However, in addition, the government has also legislated some restricted regulations for the organization‘s activities and its policies regarding the local communities, and the MNOC applies the legislations performed by the government to identify the vulnerable members of the community and to define the details of its projects for the local communities. Furthermore, a part of the agreement with the Kazakh government specifies that some parts of the community development budget should be dedicated to social projects of building local capacity, skills, and livelihoods. Decision making about the details of these social projects and their implementation is fully delegated to the MNOC. At the local level, project and community managers designed extensive diverse plans in order to maximize the benefit gained from this budget allocation.

In contrast to Case 3, local communities in Case 4 are actively involved in decision-making processes. An association is established with the aim of “responding to local concerns by providing more support and employment opportunities” (community manager). It allows for “strengthening the relationships with local people, building trust and confidence” (community representative).

The association is mainly driven by the individuals from local communities:

Our members … are usually the people from the area; they are not like the final beneficiaries, but they are people living in that same area. So, the activities are completely embedded in the communities … It has to do with the people; it engages the people as those who deliver the program, and it engages the same people also to evaluate whether it has been effective or not (project manager).

The communication with local communities is not limited to meeting community representatives or addressing complaints but is extended to bimonthly public hearings in the town hall, suggesting thorough interactions between the local communities and the MNOC. These communications informed project decision makers about certain concerns and values of the local communities:

At the beginning, we received several complaints about the air pollution during public hearings. We realized that we need to make them assured that the risk is being controlled. And so we installed these signs showing the air quality. (Project manager).

I noticed that there are two groups of people living here. Younger people prefer to have a modern life, while older population prefers to keep their traditional lifestyle…This is a tough task but we try to satisfy both groups. (Community managers).

The majority of international project personnel reside outside of the villages in order to “manage a very moderate integration with the local communities” (Project manager), but the relations between project personnel and local communities exceed official project-related communications and are infused in the day-to-day lives of the local communities and project personnel:

Their children attend the local schools, and [the project personnel] enjoy dining in the local restaurants (community manager).

Through systematic training programs, communities’ representatives receive new knowledge and skills in communities’ needs assessments and the delivery of social projects:

We train them how to find the need for improvement and how to develop the proposals, and they are the ones who choose and activate their project teams under our supervision. So, in that case, they actually become an active part of the project, the implementer (community manager).

These trainings not only develop the capacity of the organization to recognize the care but also, through better interactions with local communities, enhance the organization’s responsiveness. Holding national and religious feasts in collaboration with the communities as well as sponsoring sanatorium treatments for senior community members and summer camps for schoolchildren are among the social projects deployed by the MNOC in Case 4. It can be observed that the local communities and project personnel over time have developed a common sense of belonging:

I have been living in Aksay for nine years. My wife is here with me and we have a four years old daughter and we blend very well with the Kazakh style of living. My daughter goes to a Kazakh school and she has very close friends there (Project Manager).

Going to the sanatorium in the forest is very popular among locals here. To change the scene, or to get a different diet or just to get their health checked by the doctors (Noncommercial organization representative).

There is a parade to celebrate the 2nd World War in the town as there are still some of the soldiers living here. We all actively participate in holding this celebration. (Project manager).

To maximize local content in project development, the MNOC assists the manufacturers and contractors in the area in developing their capabilities to the standard level of the project’s demands. Due to the development programs designed and implemented by the MNOC, currently, 70 percent of the contractors of the project are local and directly recruit the local population for their workforce. While providing domestic goods and services clearly benefits the MNOC, the communities also take a share of the project benefits:

These initiatives are long-term programs, which allow the national personnel to develop their qualifications to grow in their careers … they allow the local manufacturers to develop new skills in producing the goods that we need in the project and create jobs inside their companies (community manager).

Apart from project-relevant recruitment, the MNOC financially supports small businesses by providing them with loans to develop their professions away from the oil sector by self-employment:

The oil sector has been invading the area. It is the leader, but other businesses must catch up (Noncommercial organization representative).

The empirical findings of this research suggest that among the four studied cases, the local communities in Case 4 were more protected regarding their vulnerabilities and received relatively better care from the MNOC. The condition at the local level of this case is drastically different from Case 3 that was deployed by the same focal organization. In the next section, I will discuss the factors contributing to the differences and similarities in the conditions of different cases.

Discussion

Analysis of the collected data from the organization and local level of the four cases indicates that accomplishing the process of giving care to the local communities depends on three incorporated components; the focal organization, the individuals at the organization’s border, and the conditions of the context.

As I will discuss in this section, the mature justice and the inclination to care conceived at the focal organization prepare the condition for carrying out the caring activities by individuals at the local level. Through close communications with communities, project decision makers at the local level recognize the demanded care of local communities and develop the organization’s capacity of caring. The process of care-giving can be enforced or ceased by the conditions of the context such as the influence of the government, media, and other powerful stakeholders. Deconstructing the organization’s care-giving practices leads to replacing the black and white dualism of the justice and care with a spectrum along which these three components together determine to what extent the demanded care is received by the local communities.

The Focal Organization

An organization with an inclination to justice, such as the NOC, steps into the local communities’ planet equipped with detailed plans that are designed based on the organization’s universal duty and reasoning (Noddings 1984). Such an organization effectively considers relationships as threats to the moral integrity of the entity since they can impose new roles on moral agents and curb their freedom in decision making (Borgerson 2007). The organization distantly rationalizes what must be done for local communities based on its understanding of their needs (Machold et al. 2008) or, in immature settings such as the NOC, the organization’s needs (Kohlberg 1974; Kohlberg 1981; Liedtka 1996). These plans are determined, unshakable and static, since they are designed based on justice as defined by the organization and are implemented at the local level regardless of the demanded care of the local communities.

An organization with the inclination to care for stakeholders prepares a flourishing environment that facilitates the process of providing care at the local level (Noddings 1984). At the focal organization, formal contracts, codes of ethics, and mission statements are more likely established to drive the organization’s direction (Wicks 1996). Established over shared understanding of societal norms and values or certain universal principles (Simola 2003), these agreements provide the sources of ethical reasoning for an organization’s personnel at the local level. They could be formed from the internal norms of the organization or norms generated by external bodies, such as associations, and become an integrated part of the organization’s ethical climate (Victor and Cullen 1988).

The process of moral decision making for the selection and application of these agreements at the organization level indicates that it is in fact the mature justice at the focal organization that paves the way for performing caring activities at the local level. In claiming so, I concur with Tong (1995) as well as Burton and Dunn’s (1996) suggestions to not completely exclude justice for the sake of care since these two factors are complementary attributes of fulfilling responsibilities to others. In addition, these agreements are the parts that distinguish the organization as an entity, “from its relationships and individual stakeholders,” but are grounded in and connected to them (Wicks 1996, p. 527).

These agreements, however, hard as they may try, cannot adequately prescribe, a priori, what the demanded care is in a concrete situation at the local level and how the caring activities must be accounted for. In the MNOC, for instance, while giving care was claimed to be the universal main component of the organization’s duty, it could not be distantly rationalized and should rather be defined relatively and practiced according to the context of the relationships at the local level (Noddings 1984; Nicholson and Kurucz 2019). That is why the agreements developed at the organization level of the MNOC in Case 3 transformed into empty shells of irrelevant community development programs, such as the now abandoned hospital, resulting in the perceived careless behavior of the organization, and that is the reason the plans deployed in Case 4 were positively realized by the recipients of care. The difference was made at the organization’s border where individuals from the local community and the organization interact with each other.

What has to be underlined here is that despite preparing the ethical climate to facilitate the caring activities and the willingness to care about local communities, the focal organization of the MNOC fails to undertake a comprehensive caring process. That is due to the fact that while care-giving, or carrying out the caring activities, is delegated to the local level, empathy, or ensuring that the caring needs are met, as well as responsiveness, or interaction between the giver and recipient of care, was not embodied by this organization (Tronto 1993). As elucidated by Noddings (1984), even with the best possible intentions, a care-giver may sometimes fail to bring beneficial changes to the life of recipients of care. That is why ethics of care requires the care-giver to go beyond care-giving and to constantly, critically analyze how care is received and what impacts it had on the care recipients. This of course sheds light on the importance of close communication between the care-giver and recipients of care, which due to the distance between the MNOC and the local communities, could have been planned to be enacted differently. Without this communication and analyzing the response from local communities, the focal organization of the MNOC had little knowledge from how care-giving activities were enacted at the local level.

The distorted perception of managers at the organization’s headquarter regarding what is going on in Case 3 suggests that the focal organization essentially does not know whether its intention of caring is being carried out at the local level of its projects. It can be argued that neglecting this dimension of care by the MNOC has resulted in project personnel’s ethical norms, or conditions of the context, prevailing over the organization’s ethical will.

The Individuals from the Both Sides of the Organization’s Border

A justice-oriented organization, such as the NOC, is defined by its established borders between the self and the others (Noddings 1984; Wicks et al. 1994; Held 2006). Such an organization may discourage its personnel from adopting more responsive, care-giving behavior, and in doing so, devalues its relationships with external individuals. The care-oriented organization, on the other hand, defines itself embedded in a nexus of relationships and thus has blurred borders (Burton and Dunn 1996). In doing so, an organization such as the MNOC provides an ethical culture that encourages carrying out the caring activities at the local level and determines a special place for relationships in its governance structure.

An organization’s decision makers at the local level (project managers, community managers, etc.) can become connected to the focal organization and adopt its ethical culture (Victor and Cullen 1988; Wicks 1996), and in turn can contribute to blurring the organization’s borders by embodying care, or making them bolder by embodying justice.

Despite the difference in inclination toward immature justice, and mature justice and care at the organization level of the NOC and MNOC, the conditions at the local level of Cases 1 and 3 are very similar. The organizations’ decision makers live in large compounds far from the local communities, separated by literal walls, and have no interactions with the local communities. This condition does not allow them to acknowledge their other identities. Bringing their organizationally defined roles into their work (Liedtka 1996), they can readily marginalize local communities’ demanded care in their decisions (Schnake 1991). The difference in Case 4 was that the caring activities were enacted at the local level, where organization’s decision makers used their authority to actively take the lead in caring for the individuals in their proximity, and local communities experienced close relationships with them.

The relationships built between project personnel and local communities at the local level in Case 4 allowed for acknowledging the existence of several selves of the local communities and, together with diverse community social projects, facilitated the creation of a common social self within a sort of clan that fosters development of common experiences (Young 2011). Drawing from the concept of relational self (Bondy and Charles 2018), it can be argued that an international project manager can never see the world through the eyes of a Kazakh local community. However, by living in the same town as local communities, participating in their ceremonies, and sending her/his child to a local school, over time, s/he can develop a part of her/his identity that is strongly linked to the same experiences as those of the local communities. The duty of the individuals, from the organization side of the border, would then be transformed into the responsibility to the individual’s self, which would naturally be more actively willed to be fulfilled (Borgerson 2007; Card 2010). The project personnel’s sense of belonging to the local communities would cause their voices to be heard since, in their day-to-day decision making, the project personnel internally and externally engage with the local communities and their demands and consider them in their decision making.

Enriching multiple selves through defining the self in relation to others (Bondy and Charles 2018) is not limited to the individuals from the organization side of the border. The local communities that are actively involved in decision making, alike, gradually develop their identity on the organization side of the border. While Young’s (1997) asymmetric reciprocity suggests that a careful and respectful dialogue must replace the impossible mission of seeing the world through others’ eyes, I here elucidate that, by developing, acknowledging, and highlighting relational dimensions of the individuals, this bidirectional dialogue can be accomplished not only in public hearing sessions but also internally among multiple selves of the enriched individuals.

The interrelation between local communities and project personnel does not remain static at the individual level. To enhance their capabilities and to reach a collective collaborative level, the individuals developed complex meso-groups with other individuals with similar interests, objectives, and responsibilities. In Case 4, for instance, several social project teams, led by trained community representatives and supervised by the community managers from MNOC, aimed at building capacity, skills, and livelihoods of youth, women, and vulnerable members of the community as well as business owners in the similar sectors. It was through this close relationship that the organization’s knowledge from the local communities’ demanded care was constructed, and caring activities were practiced.

In such conditions, due to their proximity, the practices of the care-giver and care receiver become highly adaptive to the changes in the values, emotions, and demanded care of the communities, and embracing the processes of change becomes a natural part of the experience. It can thus be concluded that while the recognition of the need to care (attentiveness) and the willingness to do something about the situation (responsibility) are conceived at the organization level, it is only at the local level where the capacity to do something about the situation, carrying out the caring activities and interaction between the care-giver and recipient of care, result in the desired outcomes of care-giving..

The Conditions of the Context

According to the literature of the ethics of care, a care-giving organization downplays the strict hierarchy of a stakeholder network by distributing power among them (Wicks et al. 1994), and balancing the unequal power relations between the organization and some of the least powerful stakeholders, such as the local communities (Sevenhuijsen 2003a, b; Machold et al. 2008). Accordingly, in a care-giving organization, the relationships define the levels of power that stakeholders gain in the network, so the focal organization plays an active role in forming the power dynamics of its network.

It can be argued that the literature of ethics of care implicitly assumes that the organization is the most powerful member of a network of stakeholders and can freely decentralize power by sharing it with other members of the network. Nevertheless, it is highly probable that the network includes other powerful members, such as the government or important families of the area, that have no intention of caring about the demands of the least powerful stakeholders. These powerful stakeholders can then become a barrier to care-giving practices since they limit the freedom of the organization to actively change the power dynamics of the network. Furthermore, other members of the network, such as media or local authorities, might also enable a change to the power dynamics of the network by vocalizing the demanded care of the local communities.

The MNOC in Cases 3 and 4, alike, allocated some budget for community development projects. In Cases 3, the majority of this budget was depleted by the government’s predefined plans for infrastructure developments. While the focal organization was stuck in the game of power played with the government, the conditions at the local level did not help to facilitate care-giving to the local communities. The important families of the area monopolized the supply chain of the workers and limited the opportunities of local communities for recruitment in the project. The organization’s decision makers avoided communications with local communities, and consequently, the organization’s activities caused considerable harm to the local communities and forced them into an even more vulnerable position.

In Case 4, on the other hand, although the Kazakh government had the same emphasis on infrastructure development, it had also legislated some restricted regulations for the organization's activities and its policies regarding the local communities. In comparison to Case 3, the power hierarchy within the local communities was flatter and the organization’s personnel at the local level paid special attention to the least advantaged members of the network so that they were not harmed. Through close relationships with local communities, the organization’s decision makers identified that local communities are vulnerable to environmental degradation, becoming dependent on the organization and detached from their national and religious traditions. Accordingly, they decided to allocate the remaining part of the community development budget to protect the communities from being harmed in relation to their points of vulnerability.

By involving local communities and project personnel in community development projects and project activities, these individuals with unequal power relations engaged together and built a common sense of belonging over time (Bondy and Charles 2018). By acknowledging their multidimensional selves, the local communities’ and project personnel’s’ predefined roles in the hierarchy fragmented into multiple identities as the components of enriched stakeholders. Each enriched individual subsequently gains power from or gives power to other enriched individual with similar relational selves. The sense of belonging to a particular identity group results in bringing several stakeholders closer to each other (Wicks et al. 1994); thus, the power is more evenly distributed over the network.

A justice-oriented organization, such as the NOC, might consider providing more care to local communities as a response to the dynamics of the context (Derakhshan et al. 2019b). The media and local authorities in Case 2 rendered the local communities’ demands vocal and forced the NOC to define community recruitment programs. The context in Case 1 was not the same since these stakeholders were either not sufficiently powerful or not focusing on the local communities’ demands to enable a change in the power dynamics of the network. Consequently, the local communities remained powerless, and none of their demands were addressed by the NOC. In both cases, neither the focal organization nor the individuals were attentive to the local communities’ demands. However, in Case 2, the responsibility to care for the local communities was imposed on the organization through the context.

Contribution to the Literature

The findings from this study of how organizations interact with their local communities demonstrate a range of approaches with very different outcomes in community satisfaction and engagement. In this article, I have analyzed those approaches through the lens of the ethics of care. My analysis builds on and contributes to the literature on the application of the ethics of care in stakeholder studies (Burton and Dunn 1996; Grosser and Moon 2019; Machold et al. 2008; Wicks 1996; Wicks et al. 1994) in at least five ways.

My study provides an empirical analysis of the organization and local level of projects with different approaches of care-giving to local communities. The previous literature has discussed this issue theoretically from different perspectives. Moreover, literature on the ethics of care has focused on studying care at the micro level of individuals (Gilligan 1982; Noddings 1984), or macro level of political implications of care (Tronto 1993). However, few studies have provided detailed empirical evidence of the actualities of organizations caring for stakeholders at the meso level (André and Pache 2016). Therefore, this research can be considered as a stepping stone in enlarging our understanding from the process and practice of giving care to stakeholders and their analysis through the dimensions of care (Sevenhuijsen 2003a, b; Noddings 1984; Tronto 1993), which have long been known theoretically, but scarcely examined empirically.

Second, my empirical study indicates that giving care to local communities originates from the focal organization, where an organization with intention to care-giving decides about the development and implication of formal contracts, codes of ethics, and mission statements to create an ethical culture (Victor and Cullen 1988). The organization encourages project personnel at the local level to recognize the demanded care of local communities and to conduct caring activities at the organization’s border. My study draws from Noddings’ (1984) explanation on responsiveness and elucidates that while an organization may focus on delegating carrying out the caring activities to the individuals at the local level, it ought to always be willing to go beyond care-giving and to pay attention to the needs of the person receiving the care (Noddings 1984). Furthermore, empirical examination of the cases reveals that the process of care-giving can be enforced or ceased by the conditions of the context such as the influence of government, media, and other powerful stakeholders of the network. Through deconstructing the care-giving practices into these three components and across the dimensions of care (Noddings 1984), this study sheds light on different levels of engagement with local communities that result in contrasting levels of empowerment and satisfaction.

As a third contribution, my analysis uses the concept of “enriched stakeholders” (Bondy and Charles 2018) to show that, through introspection and acknowledging the existence of several selves, project personnel can better recognize the demanded care of local communities. Individuals’ duty would then be transformed into the responsibility to the self, which would naturally be more actively fulfilled (Borgerson 2007; Card 2010). This result speaks to the conceptual definition of the blurred borders of the care-giving organization (Wicks et al. 1994; Burton and Dunn 1996) and illustrates that the borders of an organization with enriched individuals are blurred because at the local level, where organizations’ processes unfold, individuals belong to several identity groups on both sides of this border and have a multidimensional self that cannot be essentially positioned on one side of the border. I enlarge this literature by taking one step further from Young’s (1997) asymmetric reciprocity and elucidate that, by developing, acknowledging, and highlighting other relational dimensions within individuals, the dialogue between organization and stakeholders can occur not only in public hearing sessions but also internally among multiple selves of the enriched individuals.

Fourth, this study extends the literature by addressing skepticism about the issue of the size of organizations, raised by Iannello (1992) and Liedtka (1996), who determined that caring is impeded in large organizations and sharp hierarchies. The results of my research suggest that despite organizations in a large and complex setting of a multinational industry might have a well-defined hierarchy at the organization level, the focal organization with the inclination to caring must consider increased levels of authority for project personnel at the local level and empower local communities to provide a flatter hierarchy at that level. Extending from Noddings (1984), my research empirically elucidates that more successful community caring results from moving beyond the top-down approach of determining needed care to a more collaborative community care approach that is more loaded on the local level, is more democratic (Banerjee 2008), and negotiable (Blowfield 2005). In such an environment, the recognition of the demanded care, the performance of caring activities, and the interactions between the care-giver and recipient of care are all enacted by authorized virtuous individuals at the local communities’ planet.

Finally, deconstructing the organization’s care-giving practices into their three main components of the focal organization, individuals at the organization’s border and the conditions of the context, leads to replacing the black and white dualism of the justice and care with a spectrum along which these three components together determine to what extent the demanded care is received by the local communities. While this study builds on the older understanding of ethics of care, it also provides a bridge forward by examining the shades of the care received by the local communities. I believe that this work is an important contribution to the business ethics literature since it connects to the recognition that care and justice are not strictly distinct and mutually exclusive. Instead, the focal organizations’ inclination toward care must be accompanied by mature justice grounded over a shared understanding of societal norms and values (Kohlberg 1974, 1981). Justice and care both have some useful characteristics and are complementary, but most importantly, they are culturally and socially constructed.

Limitations and Future Studies

I acknowledge the limitations of my research that can be structured under two major reasons. First are the limitations relevant to the contextual conditions of the cases explored during this research, and second are those due to the decisions I made during the design of the research. One such limitation concerns the extent to which we can generalize from the empirical findings. However, precise and rigorous are the process of data collection and data analysis, case-based research does not allow for statistical generalizability, though it definitely allows for analytical generalizability (Eisenhardt 1989). Thus, the findings of this research should be interpreted in relation to their context. Future studies may examine, interrogate, and extend the results of this research through theory testing statistical approaches and within different contexts.

The findings of this research represent one relatively unique industry in which focal organizations are usually distal from the communities and have a long-standing reputation but of an exploitive and environmentally damaging nature to local communities (Idemudia and Ite 2006). Focusing on the extraction industry with such unique characteristics has resulted in identification of three components, which, incorporated together, define the position of care receiving by its targets along a black and white continuum. I believe the next stage of researchers who investigate other sectors will identify other factors beyond these three. Researching other industries that inherently had more immediate local benefit, as opposed to extractive industries, or some cross-sector partnerships or locally initiated projects might offer the potential for other measurement opportunities such as community surveys or other assessments of real local benefits. While based on my suggestion here, both the approach and context would be quite different from what I conducted in this research, concurring with Wicks (1996), I believe that the question of “how can organizations better engage with local communities?” might be best informed by the experience of success from different industries and types of partnerships. What I contributed in this research is an initial framing of a model of key factors that begins to theorize the enactment of care.

Finally, as my intention was to compare organizations with notably different approaches to local communities as well as communities that present diverse levels of satisfaction from the care they receive, these criteria took the lead in the case selection. Even though this decision in research design resulted in beneficial outcomes, it also led to analyzing the cases that are located in different countries with dissimilar cultures and societal conditions. Future research might consider exploring the cases that keep some certain contextual factors similar in order to extend our understanding from further factors that influence the process and practice of care-giving.

References

André, K., & Pache, A. C. (2016). From caring entrepreneur to caring enterprise: Addressing the ethical challenges of scaling up social enterprises. Journal of Business Ethics, 133(4), 659–675.

Banerjee, S. B. (2008). Corporate social responsibility: The good, the bad and the ugly. Critical Sociology, 34(1), 51–79.

Blowfield, M. (2005). Corporate social responsibility: Reinventing the meaning of development? International Affairs, 81(3), 515–524.

Boholm, A. (1998). Comparative studies of risk perception: A review of twenty years of research. Journal of Risk Research, 1(2), 135–163.

Bondy, K., & Charles, A. (2018). Mitigating stakeholder marginalisation with the relational self. Journal of Business Ethics, 1–16.

Borgerson, J. L. (2007). On the harmony of feminist ethics and business ethics. Business and Society Review, 112(4), 477–509.

Botes, A. (2000). A comparison between the ethics of justice and the ethics of care. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 32(5), 1071–1075.

Bowie, N. E. (1998). A Kantian theory of capitalism. The Ruffin series of the society for business ethics, 1, 37–60.

Brammer, S., & Millington, A. (2003). The effect of stakeholder preferences, organizational structure and industry type on corporate community involvement. Journal of Business ethics, 45(3), 213–226.

Burton, B. K., & Dunn, C. P. (1996). Feminist ethics as moral grounding for stakeholder theory. Business Ethics Quarterly, 2(6), 133–147.

Card, C. (2010). The unnatural lottery: Character and moral luck. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Dear, M. (1992). Understanding and overcoming the NIMBY syndrome. Journal of the American Planning Association, 58(3), 288–300.

Derakhshan, R., Mancini, M., & Turner, J. R. (2019a). Community’s evaluation of organizational legitimacy: Formation and reconsideration. International Journal of Project Management, 37(1), 73–86.

Derakhshan, R., Turner, R., & Mancini, M. (2019b). Project governance and stakeholders: A literature review. International Journal of Project Management, 37(1), 98–116.

Derry, R. (1996). Toward a feminist firm: Comments on John Dobson and Judith White. Business Ethics Quarterly, 6(1), 101–109.

Derry, R. (2012). Reclaiming marginalized stakeholders. Journal of Business Ethics, 111(2), 253–264.

Dubois, A., & Gadde, L. E. (2002). Systematic combining: An abductive approach to case research. Journal of Business Research, 55(7), 553–560.

Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989). Building theories from case study research. Academy of Management Review, 14(4), 532–550.

Fig, D. (2007). Questioning CSR in the Brazilian Atlantic forest: The case of Aracruz Celulose SA. Third World Quarterly, 28(4), 831–849.

Freeman, R. E., Harrison, J. S., Wicks, A. C., Parmar, B. L., & De Colle, S. (2010). Stakeholder theory: The state of the art. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Friedman, A. L., & Miles, S. (2006). Stakeholders: Theory and practice. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Frooman, J. (1999). Stakeholder influence strategies. Academy of Management Review, 24(2), 191–205.

Frynas, J. G. (2005). The false developmental promise of corporate social responsibility: Evidence from multinational oil companies. International Affairs, 81(3), 581–598.