Abstract

Kelly Sorensen defends a model of the relationship between effort and moral worth in which the effort exerted in performing a morally desirable action contributes positively to the action’s moral worth, but the effort required to perform the action detracts from its moral worth. I argue that Sorensen’s model, though on the right track, is mistaken in three ways. First, it fails to capture the relevance of counterfactual effort to moral worth. Second, it wrongly implies that exerting unnecessary effort confers moral worth on an action. Third, it fails to adequately distinguish between cases in which effort is required because of defects of moral character and those in which effort is required because of barriers external to moral character, such as social pressures or non-moral cognitive deficits. I suggest three amendments to Sorensen’s model that correct these three defects.

Similar content being viewed by others

In an article recently published in this journal, Kelly Sorensen (2010) explores the relationship between effort and moral worth. He begins by asking his reader to imagine two individuals who each perform the same kind of morally desirable act: they each give $100 to UNICEF, and they each do so with the aim of helping disadvantaged children. However, there is an important difference between the two agents. The first agent, Janette, makes the donation effortlessly, “she feels no internal psychological resistance” because there are “no morally bad desires working against her morally good desires” (p. 90).Footnote 1 One the other hand, Nigel, the second agent, makes the donation only as a result of struggling against a strong desire not to do so—a veritable phobia against donating. His donation is highly effortful.

Sorensen suggests that, in addition to being morally desirable actions, both of these actions intuitively possess a high degree of moral worth, which is to say that the agents warrant a high degree of moral praise for having done those acts. This is puzzling, for it is often thought that effort is relevant to moral worth, and these two actions are at opposite ends of the spectrum of effort. Nigel’s action was extremely effortful, Janette’s effortless. One might expect, then, that these actions would also be at opposite ends of the spectrum of moral worth or at least of that component of moral worth that is attributable to effort (I henceforth follow Sorensen in considering only this component of moral worth).

Our intuitive responses to these actions appear even more puzzling when we consider them alongside actions that are intermediate between them. Sorensen asks us to imagine a third agent, Lori, who performs the same kind of donation for the same reasons, but who exerts an amount of effort intermediate between that exerted by Janette and Nigel: “Lori feels a variety of self-interested desires to keep the money or spend it on something for herself. She feels these contra-moral self-interested desires with enough strength that it finally takes her considerable effort to write out her check” (p. 91). However, her self-interested desires do not amount to anything approaching a phobia against donating.

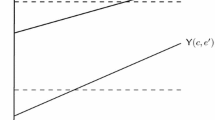

Sorensen’s intuition is that Lori’s action possesses less moral worth than the actions of Janette and Nigel. Taken together, these intuitive reactions (along with reactions to two further cases that lie at different points on the spectrum of effort) lead him to suggest that there is a U-shaped relationship between effort and moral worth: the moral worth of morally desirable actions is greatest at high and low levels of effort, and lowest at moderate levels. This, it might be thought, is puzzling.

However, Sorensen argues that these puzzling intuitions can be easily accommodated once we recognise that there are two different ways in which effort influences moral worth. He posits two core relations between effort and moral worth:

-

1.

The effort that the agent exerted in performing the morally desirable action (henceforth, ‘Effort Expended’) positively influences moral worth, in the sense that, at least over some range, increased Effort Expended makes for morally worthier action.

-

2.

The effort required for the agent to perform the kind of morally desirable action that she in fact performed (henceforth, ‘Effort Required’) negatively influences moral worth, in the sense that, at least over some range, increased Effort Required makes for less morally worthy action.

These relations are, Sorensen suggests, nonlinear, such that moral worth varies more sharply with Effort Expended at high levels of Effort Expended than at low levels, and similarly for Effort Required. This allows them to explain the apparent U-shaped relationship between effort and moral worth.Footnote 2

Sorensen’s model of the relationship between effort and moral worth is, I think, close to the mark, at least if we assume, as I will, that it is intended to apply only to morally desirable actions that meet all non-effort-based conditions for possessing positive moral worth.Footnote 3 However, in this article I will argue that it goes wrong in three significant respects, and thus requires three significant amendments.

Before outlining these defects and amendments, I should acknowledge that Sorensen’s model is in fact rather more sophisticated than I have just suggested. In addition to positing relations (1) and (2), Sorensen identifies four factors that complicate the picture, either by modifying these relations, or by contributing separately to moral worth. These are:

-

A.

The Objective Demandingness of the Action. Some actions are objectively more demanding than others. For example, donating $10,000 to UNICEF is objectively more demanding than donating $100, which is objectively more demanding than donating $1. (This is so even though some agents may find it takes no greater effort to donate $100 than $1.) Sorensen suggests that the contributions of Effort Expended and Effort Required to moral worth might depend on the objective demandingness of the action (pp. 99–103). For example, high objective demandingness might enhance the contribution of low Effort Required to moral worth.

-

B.

The Source of Effort Required. Sorensen distinguishes between cases in which Effort Required is low because the agent possesses a “naturally good character” and those in which Effort Required is low because the agent has exerted effort to develop a character that makes morally desirable actions easy (p. 103). He suggests that the innateness of Effort Required might augment or mitigate the positive effect of low Effort Required on moral worth.

-

C.

The Strength of the Agent’s Pro-Moral Desires. The level of effort that an agent expends to perform a morally desirable action will depend on the strength of her ‘pro-moral’ desires. But Sorensen suggests that the strength of these desires may also independently influence the moral worth of one’s action (pp. 103–4). For example, he suggests that the presence of a strong pro-moral desire might positively influence the moral worth of a morally desirable action even if it does not lead to high level of Effort Exerted (say, because Effort Required is low).

-

D.

Agent Self-Evaluation. Finally, Sorensen suggests that the moral worth of an action might be affected by (i) whether the agent reflectively evaluates the Effort Expended or Effort Required to perform the act, and (ii), if so, whether and to what degree the agent under-rates or over-rates the values taken by these variables (pp. 104–7). He remains agnostic on the direction in which these factors influence moral worth and on whether they influence moral worth directly or by modifying the influence of Effort Required or Effort Expended.

In what follows, I first argue that Sorensen’s model should be amended to accommodate a fifth complicating factor (§1). I then argue (§§2 and 3) that the core of Sorensen’s model, which is comprised by relations (1) and (2), also needs to be amended; contra Sorensen, Effort Exerted and Effort Required do not influence moral worth, though they are close to considerations that do.

1 Counterfactual Effort

Sorensen postulates that when little effort is required to perform a morally desirable action, so that little effort is expended in performing it, the low Effort Required contributes to the action’s moral worth, but the low Effort Expended detracts from its moral worth. However, it seems plausible that the low Effort Expended would at the very least detract less from the moral worth of the action if the agent would have exerted greater effort had this been required.Footnote 4 If an agent were disposed to exert greater effort if necessary, we would, I think, attach less significance to the low level of effort that was actually expended.

Recall Janette, the first agent from Sorensen’s example. Janette donated $100 effortlessly, since her desires were all aligned in support of the donation. Consider two different ways in which Sorensen might have further spelled out the example. In the first variant of the case, Janette’s psychology is such that, if effort had been required to make the donation, Janette would have exerted it. Perhaps she is strongly motivated to donate and that motivation would have persisted in the face of strong countervailing desires, had she possessed any, and indeed would have over-ridden those desires. In the second variant, Janette’s psychology is such that, if effort had been required to make the donation, she would not have exerted it. She would not have had a sufficiently strong motivation to donate.

It seems plausible that Janette’s action in the first variant of the case possesses greater moral worth than her action in the second variant of the case. Janette’s counterfactual effort might seem to diminish the negative effect of her low level of actual Effort Expended on the moral worth of her action.

It is, moreover, possible to rationalise this intuitive response. It is widely believed that the moral worth of a morally desirable action depends in part on whether it was an accident that the agent performed a morally desirable action; as Barbara Herman puts it, “we need to know that it was no accident that the agent acted as duty required” (1981, p. 368).Footnote 5 But in the case where Janette would not have exerted more effort had more effort been required, it might seem that Janette’s performance of a morally desirable action is an accident; it is, for example, contingent on the absence of strong countervailing desires and external barriers to performing the morally desirable action.

Sorensen might argue that his model can accommodate the thought that Janette’s counterfactual effort influences the moral worth of her action. As we saw earlier, one of the factors that Sorensen mentions as a possible complication to his model is the strength of the agent’s pro-moral desires.Footnote 6 Thus, Sorensen could allow that the strength of Janette’s desire to make the donation might be relevant to the moral worth of her action even if, as it happens, a weak desire to donate would have been sufficient. Moreover, the strength of Janette’s desire to make a donation might be thought closely related to the truth of counterfactual claims about whether Janette would have exerted higher amounts of effort had this been required. One might think that the strength of Janette’s actual desire to donate is indicative of whether she would have exerted the effort required to donate in those counterfactual scenarios.

Indicative, it may be. However, the strength of an agent’s desire to perform some desirable act does not settle the truth of claims about whether she would have performed the act in counterfactual circumstances. What determines whether Janette would have exerted more effort, had it been required, is whether she would have had a sufficiently strong pro-moral desire to donate had there been some barrier to making the donation. Whether she has a strong pro-moral desire in the actual case, in which faces no barriers, may constitute evidence that she would have had a sufficiently strong desire in the relevant counterfactual cases, but it does not guarantee it.Footnote 7 In the actual case, Janette may have a very strong pro-moral desire to donate to UNICEF, but one whose presence is conditional on the absence of barriers.

Thus, an agent’s counterfactual effort cannot be subsumed under the strength of her actual pro-moral desire. If we are to accommodate the thought that counterfactual effort bears on the moral worth of an action, we will need to modify Sorensen’s model.

Two possible modifications suggest themselves. Both involve adding a further variable, which I will call Effort Limit, to the model. Effort Limit is a measure of counterfactual effort. It is the maximal level of effort that the agent would have been prepared to expend in order to perform a similarly morally desirable action had greater effort been required. Suppose that an agent exerts an amount of effort, e, to perform a morally desirable action whose degree of moral desirability is m. We can then imagine a series of hypothetical situations which are similar to the agent’s actual situation but which differ with respect to the amount of effort required to perform an action with moral desirability of at least m. In the first hypothetical situation, the level of effort required for this is slightly greater than e; in the next it is slightly greater still, and so on. At some point we first come to a situation in which the agent would not have performed an action whose moral desirability is at least m. This indicates that we have just crossed the Effort Limit.

The first way in which we could modify Sorensen’s model is to add Effort Limit as a modifier of the influence of Effort Expended. The idea would be that a high Effort Limit mitigates the moral-worth-lowering effect of low Effort Expended; the higher one’s Effort Limit, in relation to a particular action, the less a low level of Effort Expended diminishes the action’s moral worth.

The second way in which we could modify Sorensen’s model is to add Effort Limit as an independent positive contributor to moral worth—to take it as a factor that contributes positively to an action’s moral worth independently of Effort Expended or Effort Required.

We would have grounds to favour the first of these modifications if the influence of Effort Limit on moral worth differed depending on the level of Effort Expended, so that, for example, having an Effort Limit of 100 units of effort in relation to a particular action would contribute more to the moral worth of that action if one actually exerted 10 units of effort than if one actually exerted 90. By contrast, we would have grounds to favour the second modification if the influence of Effort Limit were constant across different levels of Effort Expended. I am not sure enough about my intuitions regarding the relevant cases to decide between these two alternative modifications. Thus, let me simply suggest that we ought to modify Sorensen’s model by incorporating Effort Limit in one of the two ways that I have indicated.Footnote 8

There are, of course, various objections that might be raised against this suggestion. Let me briefly discuss what I take to be the most powerful of these. This objection maintains that, though Effort Limit is perhaps relevant to the moral worth or moral virtue of the agent's character, it cannot be relevant to the moral worth of the action in question, for it is too disconnected from that action. Arguably, the moral worth of an action must be determined by considerations that are intrinsic or at least closely related to the action itself.

I cannot offer a full response to this objection here. But let me briefly explain why I am inclined to reject it. It is, I think, plausible both that (i) the moral worth of a morally desirable action depends in part on whether (or to what degree) it was an accident that the agent performed a morally desirable action, and that (ii) whether (or to what degree) it was an accident that the agent performed a morally desirable action depends in part on what the agent would have done, or what sort of psychological states he would have possessed, in certain counterfactual situations. If we accept (i) and (ii), then we must accept that some counterfactual features of the agent are relevant to the moral worth of the agent’s actual action, and if we accept this it is difficult to see why the counterfactual effort exerted by the agent could not also be relevant. Counterfactual effort is hardly more disconnected from the actual action than are other counterfactual features of the agent.Footnote 9 It thus seems that the proponent of the present objection will need to reject (i) or (ii), and since these are both plausible claims, I think this gives us at least some motivation to reject the objection.

In any case, this objection is not one open to Sorensen, for he has elsewhere defended the view that what an agent would have done, or been like, in counterfactual situations is relevant to the moral worth of her actual action (Sorensen forthcoming). Given his endorsement of the relevance of counterfactuals in general, it is doubtful that he could object to the relevance of counterfactual effort on the grounds that it is too disconnected from the actual action.Footnote 10

2 Unnecessary Effort

I have tried to show that we need to look beyond the agent’s actual action, and actual effort, in assessing the contribution of effort to an action’s moral worth. We need to look at the agent’s Effort Limit. Let me now return to the actual—that is, the actual action, the actual Effort Expended and the actual Effort Required.

Sorensen’s claim that Effort Expended positively influences moral worth while Effort Required negatively influences it could be taken to imply that the morally worthiest actions will be neither like Janette’s nor like Nigel’s. Rather, they will be actions that the agent could have done with minimal effort (thus, Effort Required is low) but in fact expended a large amount of effort in performing (thus, Effort Expended is high). Sorensen does not consider actions of this sort—he seems to assume that they are not possible—but I suspect that if he did, he would, contrary to his model, not judge them to be the worthiest actions.

It is possible for an action to involve both a low level of Effort Required and a high level of Effort Expended. An action could have these properties when the agent exerted a large amount of unnecessary effort in acting—effort that made no difference to whether she performed the kind of morally desirable action that she in fact performed. However, it seems implausible to suggest that these actions are the morally worthiest. It is difficult to see why exerting unnecessary effort should confer moral worth.Footnote 11

There are, admittedly, two sorts of case in which it might seem that exerting unnecessary effort, as I have just defined it, does confer moral worth on one’s action. One is where the effort makes no difference to the kind of action that the agent performs but does increase the moral desirability of that action, say, because the desirability of the action is determined in part by the way in which the agent came to perform it. The other is where the effort makes no difference either to the kind of action performed or to its moral desirability, but the agent reasonably believed that the effort would increase the moral desirability of the action.

In order to set aside such cases let us revise our concept of ‘unnecessary effort’ so that it focuses not on the kind of action performed but on its moral desirability, and so that it takes into account the agent’s reasonable beliefs. Let us say that effort is unnecessary when it neither made a difference to the moral desirability of the agent’s action nor was reasonably believed by the agent to make such a difference. Are there cases in which exerting unnecessary effort, thus understood, confers moral worth on one’s action?

It might seem that there are. Thus, recall again Janette, the first agent from Sorensen’s example. Janette donated $100 effortlessly, since her desires were all aligned in support of the donation. But now suppose that Janette could have donated effortlessly, given her psychological make-up, but in fact exerted a large amount of effort in making the donation because she took what she knew to be a psychologically inefficient route to donating. Rather than simply posting a cheque or making an online donation, she elected to donate by (i) entering a marathon in which the $100 entry fee is to be passed on to UNICEF for all entrants who succeed in completing the race, and (ii) exerting great effort to complete that marathon. Suppose further that Janette’s choice to donate by completing the marathon made no difference to the moral desirability of her act of donating $100 and was known by her to make no such difference.

I concede that some might intuit that Janette’s action of donating $100 in this modified ‘marathon’ version of the example is somewhat worthier than her action of donating $100 in Sorensen’s original case even though the effort she expends is unnecessary—she could just have posted a cheque. However, it is doubtful whether we should take this intuition to support the view that even unnecessary effort contributes to moral worth.

First, it is unclear whether the extra worth that we might ascribe to Janette’s action in the marathon variant of the case is really moral worth. We might think that Janette is praiseworthy for having a completed a marathon, in the ordinary sense that anyone who completes a marathon is praiseworthy, but this is not a moral kind of praise.

Second, even if we think that Janette’s action in the marathon variant of the case possesses greater moral worth than in the original variant, it is not obvious that her exertion of unnecessary effort is what confers this moral worth. I argued in the previous section that Effort Limit—the maximal level of effort that an agent would have exerted to perform an action—positively contributes to moral worth (either directly, or by modifying the contribution of Effort Expended). This raises the possibility that Janette’s completion of a marathon seems to increase the moral worth of her action only because it constitutes evidence that she has a very high Effort Limit; that she would have been prepared to exert a very large amount of effort to make the donation. Thus, it may well be that, rather than conferring moral worth itself, the exertion of unnecessary effort serves as evidence for certain counterfactual states of affairs which are what influence the action’s moral worth.

There are reasons to think that effort which is unnecessary, in our revised sense, confers no moral worth—it simply seems implausible that one should gain moral credit by exerting effort that neither makes nor is reasonably expected to make any difference to the moral desirability of one’s action. It also seems to me that intuitive responses which might seem to indicate the opposite, as in the marathon case above, can be explained away with relative ease. I thus suggest a further modification to Sorensen’s model: we should alter the relation that he posits between Effort Expended and moral worth so that it cites not Effort Expended, but Necessary Effort Expended (that is, Effort Expended minus any part of that effort that was unnecessary).Footnote 12

A more modest modification would retain the relation between Effort Expended and moral worth, but add the necessity of the effort expended as a modifier of this relation. However, it seems plausible that where the effort an agent expended is unnecessary, it has no positive effect whatsoever on the agent’s moral worth. Moreover, it seems plausible that this is so at any level of Effort Expended. These considerations suggest that merely adding necessity of effort as a factor that weakens the influence of Effort Expended does not go far enough. We should instead replace Effort Expended with Necessary Effort Expended.

3 External Versus Internal Barriers

A third factor that I believe influences the moral worth of actions is mentioned by Sorensen as a possible complication, but not, I think, adequately accommodated. This is the nature of the barrier(s) which the agent must overcome to perform the morally desirable action, or, as Sorensen puts it, the source of Effort Required. Sorensen notes that the source of the Effort Required in relation to a particular action might influence that action’s moral worth. However, he focuses primarily on one distinction that might be drawn between different sources of Effort Required. He notes that the effect of a low level of Effort Required on the moral worth of the action might depend on whether little effort was required (i) because the agent has a “naturally good character” or (ii) because the agent has struggled to, and succeeded in, developing a character that makes morally good action easy, though she did not initially possess such a character (p. 103).

In both cases, however, effort is required due to factors that are internal to the agent’s character. Yet effort could also be required to perform morally desirable actions because of external barriers. We can imagine an agent who, like Janette, has no desires that militate against donating to UNICEF, but who nonetheless must exert considerable effort to make a donation because of social constraints or forces. For example, perhaps this agent lives in a society that wishes to discourage charitable donations and has thus created labyrinthine regulations which make it very difficult to arrange them. It seems doubtful whether Effort Required due to the presence of these external barriers would detract from the moral worth of this agent’s conduct. In the cases considered by Sorensen, Effort Required plausibly detracts from moral worth because it reflects some “deficient state of character that makes the action hard” (p. 94).Footnote 13 But in the case just described, the Effort Required does no such thing. Effort is required for reasons unrelated to the agent’s character.Footnote 14

Sorensen does, in a footnote, acknowledge that some readers might want to understand ‘Effort Required’ as standing in for effort that is required due to internal barriers (p. 93).Footnote 15 But this, it seems to me, understates the issue. It is not merely that some might think that only Effort Required due to internal barriers is relevant to moral worth; rather it is very difficult to see how Effort Required due to external barriers could be relevant. Effort Required is supposed to be relevant to moral worth because it reflects some character flaw, but this is simply not the case when the effort is required for reasons external to the agent.

Perhaps Sorensen could accommodate this thought by appealing to his idea that the objective difficulty of an action modifies the contributions of Effort Exerted and Effort Required to the action’s moral worth (see his complication A above). It might be thought that labyrinthine regulations designed to discourage charitable donations make such donations objectively difficult and that this explains why the Effort Required in making a donation in such circumstances does not have its usual negative influence on moral worth.

However, it is possible to imagine cases where effort is required for reasons that reflect neither the objective difficulty of the action nor any moral defect in the agent’s character. For example, performing a morally desirable action might be difficult for an agent because of an agent’s idiosyncratic deficits in non-moral cognition. Suppose that all charitable donations in some state must be accompanied by a tax declaration that requires the donor to perform some simple calculations. The requirement to perform these calculations does not make donating difficult from an objective point of view, but it does make it difficult for some: those with especially low mathematical abilities. Those individuals would need to exert considerable effort in order to donate. It seems doubtful, however, that this Effort Required detracts from the moral worth of their donations. Though it might signal certain cognitive weaknesses, it does not reflect badly on the agent in a moral sense. The cognitive weaknesses are plausibly ‘external’ in the sense that they are not an element of the agent’s moral character (by which I mean, aspects of the agent’s character that are susceptible to moral criticism). In this respect, they are like social or environmental barriers.

More generally, to the extent that Effort Required is attributable to the presence of barriers that are external to the agent’s moral character, it is implausible that Effort Required will detract from an action’s moral worth, and insofar as those barriers are specific to particular individuals, their effect on moral worth cannot be accounted for by appealing to the objective difficulty of the action. This suggests that a third modification is called for: we should replace Effort Required, in Sorensen’s model, with ‘effort required due to barriers internal to the agent’s moral character’ or, as I will henceforth put it, Internal Effort Required.

Again, it might be argued that a less drastic modification could be made. Rather than altering the Effort Required relatum in Sorensen’s second relation, we could perhaps simply add ‘Internality of Effort Required’ as a modifier of that relation. However, I believe that this change would not go far enough, and for reasons that parallel those discussed in the last section. It seems to me that, when effort is required for reasons that are external to the agent’s moral character, this does not merely weaken the negative influence of Effort Required on moral worth; rather, in such cases, there is no negative influence at all. In such cases, the presence of Effort Required reflects nothing about the agent’s character. Moreover, this is so regardless of the level of Effort Required in a particular case. This suggests that we should replace Effort Required with Internal Effort Required rather than merely adding Internality of Effort Required as a modifier.

4 Conclusions

I have argued that Sorensen’s model, though it points in the roughly the right direction, has three defects, and thus needs to be modified in three ways. First, it should be altered so as to incorporate Effort Limit as either a modifier of the influence of Effort Expended on moral worth or as an independent contributor to moral worth. Second, the relation it posits between Effort Expended and moral worth should be replaced with a relation between Necessary Effort Expended and moral worth. And third, the relation it posits between Effort Required and moral worth should be replaced with a relation between Internal Effort Required and moral worth.

The first of these amendments is relatively peripheral to Sorensen’s main points; it involves merely adding a fifth item to Sorensen’s list of complications (see A-D above). However, the second and third amendments strike at the core of his model—namely the relations relating Effort Expended and Effort Required to moral worth. I have argued that these relations do not obtain, though they are not too far from relations that do.

Notes

All page references are to Sorensen (2010) unless specified otherwise.

The U-shaped relationship results from adding two nonlinear, convex-down curves whose slopes take the opposite signs.

Suppose an agent exerts a great deal of effort to perpetrate evil, but it turns out that the action he thinks is evil is in fact morally desirable, so his effort results in a morally desirable action. It seems very doubtful that this effort expended confers moral worth. It is also questionable whether the effort required to perform this act detracts from its moral worth. However, I believe that Sorensen could avoid such implications by restricting the scope of his claims to actions in relation to which all non-effort-based conditions for positive moral worth are met. (In the case just given, it is plausible that the agent fails to satisfy a condition that the action must be done from the right motives or for the right reasons.) I henceforth read him as accepting a restriction of this kind, both on his two core relations, and on the other influences on moral worth (A-D) outlined below. I do not attribute to Sorensen, and do not myself recommend, any particular view on what non-effort-based conditions for positive moral worth there are.

I thank Walter Sinnott-Armstrong for pressing me to consider this possibility.

I assume that, by ‘pro-moral desire’, Sorensen means to refer to any motive for performing a morally desirable action that meets all of the non-effort-based conditions for that action to possess positive moral worth.

Sorensen does acknowledge, on p. 95, that the contribution of low Effort Required to moral worth may be explained by the fact that morally desirable actions that require little effort actualize “settled, robust good character traits”. If ‘robustness’ is understood here in counterfactual terms, this comes close to acknowledging that counterfactual effort is relevant to the moral worth of an action. However, Sorensen does not consider the presence of these robust traits to be an independent influence on the moral worth of actions, nor does he take them to modify the influence of Effort Required or Effort Expended. Insofar as he views these traits as relevant to the moral worth of actions he sees them only as part of an explanation for the influence of Effort Required.

If we accept Effort Limit as an independent contributor to moral worth, an interesting question arises regarding whether there is any reason to retain Effort Expended as a separate contributor. The actual effort exerted in performing an action tells us something about the amount of effort that the agent would have exerted to perform such an action. More specifically, if an agent exerts x units of effort to perform an action, we know that Effort Limit, in relation to that agent and action, is at least x. It might be thought that this evidential role played by Effort Expended exhausts its relevance to the moral worth of an action. Arguably, assigning Effort Expended any separate significance would violate a requirement that our moral appraisal of an agent should not depend on factors beyond the agent’s control, since the amount of effort that an agent actually has to expend to perform a given action will often not be within that agent’s control. On the other hand, there are well-known arguments against the existence of such a requirement (see especially Nagel 1979). Nagel argues that features of the actual situation rightly influence our moral assessment of an agent’s action even where their presence is a matter of luck from the point of view of the agent.

I cannot settle the dispute between Nagel and his critics here, and for that reason among others I will remain neutral on whether Effort Expended should be retained alongside Effort Limit as an influence on moral worth. My claim is merely that Effort Limit has some positive bearing on the moral worth of an action. For a more general discussion of the relative importance of counterfactual and actual considerations to the moral worth of an action, see Sorensen (forthcoming).

I am not claiming here that Effort Limit is the only counterfactual consideration, or indeed the only measure of counterfactual effort, that plays a role in determining the moral worth of an action.

A variant of the objection I discuss here would maintain that counterfactual effort cannot influence the moral worth of an action because that would make the moral worth of the action equivalent to the moral worth of the agent’s character, whereas it is plausible that there is a distinction between these two things. However, we can allow that Effort Limit influences character while accommodating this distinction. First, the moral worth of an agent’s character will plausibly depend not just on the agent’s Effort Limit in relation to a single actual action, but also on the agent’s Effort Limit in relation to other (possible or actual) actions of hers. Second, it may be that the relative weighting to be given to actual considerations (such as Effort Expended and Effort Required) and counterfactual considerations (such as Effort Limit) differs depending on whether it is the moral worth of an action of the moral worth of the agent’s character that is in question.

For discussion of this point, see also Douglas (2013).

As I have defined my terms, Necessary Effort Expended includes both effort that makes a positive difference to the moral desirability of the agent’s action and effort that is falsely but reasonably believed by the agent to make such a difference. However, I remain open to the possibility that effort of the latter sort should in fact be excluded. The point I wish to make is that we should exclude effort that neither makes a difference nor is reasonably believed to do so.

Others have also defended the thought that the moral worth of an action is the degree to which it reflects well on the moral character of the agent. See, for example, Markovits (2010), p. 203: “Morally worthy actions are ones that reflect well on the moral character of the person who performs them. This is not to say that only virtuous people can perform worthy actions—it is possible to act, in this sense, out of character. But morally worthy actions are the building blocks of virtue—a pattern of performing them makes up the life of a good person.”

See also p. 94, note 8.

References

Arpaly N (2003) Unprincipled virtue: an inquiry into moral agency. Oxford University Press, New York

Douglas T (2013, forthcoming in print) Enhancing moral conformity and enhancing moral worth. Neuroethics. doi:10.1007/s12152-013-9183-y

Foot P (1978) Virtues and vices and other essays in moral philosophy. University of California Press, Berkeley

Herman B (1981) On the value of acting from the motive of duty. Philos Rev 90(3):359–382

Hursthouse R (2000) On virtue ethics. Oxford University Press, New York

Markovits J (2010) Acting for the right reasons. Philos Rev 119(2):201–242

Nagel T (1979) Moral luck: Mortal questions. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp. 24–38

Sorensen K (2010) Effort and moral worth. Ethical Theory Moral Pract 13(1):89–109

Sorensen K (forthcoming) Counterfactual situations and moral worth. J Moral Philos

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Kelly Sorensen and two anonymous reviewers for Ethical Theory and Moral Practice for their comments on an earlier version of this manuscript. I thank the Wellcome Trust (grant number WT087211) for their funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Douglas, T. The Relationship Between Effort and Moral Worth: Three Amendments to Sorensen’s Model. Ethic Theory Moral Prac 17, 325–334 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10677-013-9441-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10677-013-9441-4