Abstract

Contrastivism is the view that knowledge is a ternary relation between an agent, a content proposition, and a contrast, and it explains that a binary knowledge ascription sentence appears to be context-sensitive because different contexts can implicitly fill the contrast with different values. This view is purportedly supported by certain linguistic evidence. An objective of this paper is to argue that contrastivism is not empirically adequate, as there are examples that favor its contextualist cousin. Thereafter, I shall develop a contextualist account for the relevant linguistic data. The account consists of a contextualist semantics and some rules of pragmatics. The two parts combined show that contrastivism is neither sufficient nor necessary as a satisfactory theory of knowledge ascriptions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Not applicable.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Notes

Contrastivists may not have a consensus on what “knowledge is a ternary relation” means. For example, Schaffer (2004) defends the view that this ternary relation is the denotation of the verb “to know” in our ordinary language, according to which contrastivism amounts to a descriptive theory of our knowledge ascription language and the concept of knowledge that is denoted by it. On the other hand, Sinnott-Armstrong argues for a revisionist version of contrastivism, which indicates that the ternary relation is what we should make use of if the goal is to “describe a person’s epistemic position as precisely as possible” (2008, p. 268). This paper is focused on the descriptive version of contrastivism that is put forth in a series of papers by Schaffer.

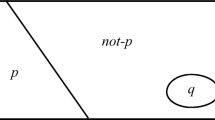

Ternicity alone cannot distinguish contrastivism from contextualism. In the literature, the contextualist can treat “to know” as either an indexical or a predicate that has a third argument (cf. Bach, 2005, Montminy, 2008, and Baumann, 2016). The latter kind of contextualism is compatible with Ternicity. Thanks to an anonymous reviewer for this point. However, I do not think these contextualist views can agree with the other contrastivist thesis introduced below, i.e. Saturation. For the contextualist, even if she stipulates a third argument position of “to know”, she treats it as an argument whose value has to be determined by the context. On the other hand, if the contrastivist is right, the third argument can be saturated by contrast expressions alone.

Sometimes the contrastivist takes the view as a variant of contextualism in the sense that they both allow the shiftiness of binary knowledge ascription: “This is because the contrastive view allows that one ascriber could truly say ‘s knows that p,’ while a second ascriber in a second context (with a different range of relevant alternatives) could truly deny ‘s knows that p.’ ” (Schaffer & Knobe, 2012, p. 687) However, this is just a terminological difference. I will use the term “contextualism” in a stronger sense that excludes contrastivism, and the distinction is made by the thesis of Saturation below.

Originally in Schaffer and Knobe (2012), these sentences read ‘Mary now knows...’ But here the word ‘now’ is dropped. Given that Gerken and Beebe (2016, pp. 139–142) are able to replicate the experimental results, and given that the conditions they use are exactly like those used by Schaffer and Knobe except that ‘now’ is dropped, it seems fair to present Schaffer and Knobe’s data with this minor change.

Schaffer and Knobe (2012) do think that contrastivism successfully explains the contrastive effect shown by the pair in (6a). One reason why I set them aside is that it seems not clear to me how the contrastivist theses, i.e. Ternicity and Saturation, could be extended to cover knowledge-wh ascriptions, especially when the aim is a compositional semantics that preserves the uniformity of “to know”. For example, Schaffer (2009) proposes that a knowledge-wh ascription, with Q being the question that corresponds to its embedded wh-clause, is true iff there is a proposition p such that KspQ and p is the true answer to Q. But I do not see how this existentially quantified truth condition could be unified with the version of contrastivism for knowledge-that ascription, so it seems better, for my purposes, to focus on only knowledge-that ascriptions at this point. For Schaffer’s view on knowledge-wh ascriptions and relevant discussions, see Schaffer (2007b), Schaffer (2009), Brogaard (2009), Kallestrup (2009), Aloni and Égré (2010), and Steglich-Petersen (2014).

An anonymous reviewer raises the concern that this response presupposes the denial of contrastivism. In particular, the speaker’s defense, that Mary doesn’t know that Peter rather than anyone else stole the rubies, is directly against contrastivism. According to contrastivism, as Mary can rule out the contrast, i.e. that someone else stole the rubies, the knowledge denial should be false. However, the argument above is meant to rely on our intuitive judgment about the speaker’s defense. As it appears to me, the speaker’s defense is somewhat acceptable, while it is hard to imagine how (11) can be defended in any sensible way. If there is this difference between (11) and (12), I think it suffices for the main point here: unlike ternary ascriptions of paradigmatically ternary relations (e.g. the introduction relation), a ternary knowledge ascriptions can be true in a context and be false in another.

Theoretically, it is possible for the contrastivist to give a pragmatic account of the infelicity of (13). She can insist that the sequence expresses two true propositions, while explaining the infelicity by pragmatics. Thanks to an anonymous reviewer for this point. However, it is not clear to me what pragmatic account is available for the contrastivist, as similar sequences of ternary relation ascriptions does not seem to violate any pragmatic rules. For example, (18) below sounds felicitous. In the end, I think it is the burden is on the contrastivist to show that there are pragmatic accounts that work in her favor.

This is an over-simplified formulation of epistemic closure. For this conditional to hold, the relevant subject arguably has to know that p entails q, deduce q from p, and thereby come to believe that q in virtue of that deduction. Conditions of this sort are omitted here for two reasons. First, it is still controversial which of them should be added to closure. Second, we can assume that the examples considered in this paper all satisfy these conditions, no matter what they may include. For example, we can assume that Moore believes that having hands entails not being a BIV, he deduces that he is not a BIV from the premise that he has hands, and he comes to believe that he is not a BIV in virtue of the deduction.

Expand-p is only part of the contrastivist version of closure in Schaffer (2007a). There is a parallel principle concerning the contrast position and two other principles covering multi-premise cases:

Contract-q: If one knows that p rather than q, and if q is entailed by \(q'\) and \(q'\) is not necessarily false, then she knows that p rather than \(q'\).Intersect-p: If one knows that \(p_1\) rather than q, and if she also knows that \(p_2\) rather than q, then, with certain other conditions satisfied, she knows that \(p_1\wedge p_2\) rather than q.

Union-q: If one knows that p rather than \(q_1\), and if she also knows that p rather than \(q_2\), then, with certain other conditions satisfied, she knows that p rather than \(q_1\vee q_2\).

For our purposes, we only have to focus on Expand-p, as one of its counterexamples illustrates that the shiftiness of knowledge ascriptions cannot be eliminated by explicit contrast expressions.

Similar to the binary version of epistemic closure (see fn. 9), Expand-p also requires provisos about how the subject in question comes to believe that \(p'\), or, if belief is also contrastive (cf. Blaauw, 2012), how the subject comes to believe that \(p'\) rather than q.

In Hughes (2013, pp. 586–589), what functions as the skeptical proposition is that Moore (or any other subject) is a BIV. I think both counterexamples work well, but the skeptical proposition I choose here better reflects the role it plays: S(p, q) is a proposition that the subject in question cannot differentiate by evidence from q while being incompatible with p.

It is easy to find similar examples which do not rely on skeptical possibilities. Adapting an example from Dretske (1970), starting from the ordinary knowledge (a), allows us to infer (b).

- (a):

-

Moore knows that it is a zebra rather than a mule.

- (b):

-

Moore knows that it is a zebra and not a cleverly disguised mule rather than a mule.

However, (b) is intuitively false (assuming that Moore is no expert in zoology).

However, as the new contrast \(S(p,q)\vee q\) is equivalent to the original contrast q, (22) still follows from (20) by Contract-q (see fn. 10), which is another principle in Schaffer’s (2007a). Therefore, this proposal does not work in the contrastivist’s way, if she is to defend Schaffer’s whole package of closure. Thanks to an anonymous reviewer for this point.

To be clear, there are exceptions where NRCs seem to take a narrow scope, but it is safe to say that they tend to take the widest scope. See Fabricius-Hansen (2020) for a recent survey.

Not all theories of NRCs are multi-dimensional. For example, Schlenker (forthcoming) develops a unidimensional semantics. But in his theory, it is the syntax that serves to separate an NRC and its main clause. The semantic values of the two are calculated independently first, though they are combine to form the unique semantic value of the sentence at the last step.

A serious contextualist semantics must be much more complex than this. For example, the current semantics doesn’t even entail the factivity of knowledge, nor the belief condition. These are, of course, a shortcoming, but it does not matter for our purposes here. Indeed, we can cast these conditions as semantic constraints on the epistemic state: the actual world must be a member of the epistemic state, and the epistemic state must be a subset of the agent’s doxastic state.

This notion is in line with a well-established view on the semantic interpretation induced by focus—focus triggers a set of alternative propositions. In this sense, the notion of congruent question is the same as “focus semantic value” in Rooth (1985, 1992), the set of “focal alternatives” in Roberts (2012), and “current question” in Simons et al. (2017), etc..

This notion of Congruent Question is slightly different from Roberts’s view. For Roberts, congruent questions are only derived at the whole sentence level and do not apply to embedded clauses. But the move I’m making here is a natural extension of her approach, given that the embedded clause in a knowledge ascription, as illustrated above, should be congruent with the epistemic question in the context in the same way as whole sentences should be congruent with the contextually determined question under discussion.

A compositional derivation of sets of alternative propositions (i.e. congruent questions) can be found in Abusch (2010). He treats the and-not construction (e.g. John is in Boston and not New York) as triggering a set of alternative propositions (i.e. a congruent question) and doesn’t mention rather-than, but it strikes me that the two are nothing different.

Formally: \(\exists p_1, p_2\in Q_c\exists w_1, w_2 \in R_c [w_1\ne w_2\wedge (w_1\in p_1\wedge w_1 \notin p_2) \wedge (w_2\in p_2 \wedge w_2\notin p_1)]\).

Formally: \(\forall w\in R_c \exists p\in Q_c (w\in p)\).

Schaffer and Knobe (2012) take the two questions as questions under discussion. I beg to differ: the knowledge ascription “Mary knows that Peter stole the rubies” is not a congruent answer to either question, in the sense of Roberts (2012, pp. 31–32). Although before the knowledge ascription is uttered, they seem to be the questions under discussion, because of the incongruence of the ascription to it, some other questions must be accommodated as the immediate questions under discussion, say, Who was the person that stole the rubies, according to what Mary knows? and What did Peter steal, according to what Mary knows?. But given these newly accommodated questions under discussion, the previous two questions now become the epistemic questions respectively in the two contexts.

References

Abusch, D. (2010). Presupposition triggering from alternatives. Journal of Semantics, 27(1), 37–80.

Aloni, M., & Égré, P. (2010). Alternative questions and knowledge attributions. Philosophical Quarterly, 60(238), 1–27.

Bach, K. (2005). The emperor’s new ‘knows’. In G. Preyer & G. Peter (Eds.), Contextualism in philosophy: Knowledge, meaning, and truth (pp. 51–89). Oxford University Press.

Baumann, P. (2016). Epistemic contextualism: A defense. Oxford University Press.

Blaauw, M. (2012). Contrastive belief. In M. Blaauw (Ed.), Contrastivism in philosophy: New perspectives. Routledge.

Blome-Tillmann, M. (2009). Knowledge and presuppositions. Mind, 118(470), 241–294.

Brogaard, B. (2009). What Mary did yesterday: Reflections on knowledge-WH. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 78(2), 439–467.

Cohen, S. (1999). Contextualism, skepticism, and the structure of reasons. Philosophical Perspectives, 33, 57–89.

Dretske, F. I. (1970). Epistemic operators. Journal of Philosophy, 67(24), 1007–1023.

Dretske, F. I. (1972). Contrastive statements. Philosophical Review, 81(4), 411–437.

Fabricius-Hansen, C. (2020). (Non)restrictive nominal modification. In D. Gutzmann (Ed.), The Wiley Blackwell companion to semantics (pp. 1–32). Wiley.

Gerken, M., & Beebe, J. R. (2016). Knowledge in and out of contrast. Noûs, 50(1), 133–164.

Hamblin, C. L. (1973). Questions in Montague English. Foundations of Language, 10(1), 41–53.

Hughes, M. (2013). Problems for contrastive closure: Resolved and regained. Philosophical Studies, 163(3), 577–590.

Kallestrup, J. (2009). Knowledge-WH and the problem of convergent knowledge. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 78(2), 468–476.

Karjalainen, A., & Morton, A. (2003). Contrastive knowledge. Philosophical Explorations, 6(2), 74–89.

Lewis, D. K. (1979). Scorekeeping in a language game. Journal of Philosophical Logic, 8(1), 339–359.

Lewis, D. K. (1996). Elusive knowledge. Australasian Journal of Philosophy, 74(4), 549–567.

Montminy, M. (2008). Can contextualists maintain neutrality? Philosophers’ Imprint, 8, 1–13.

Morton, A. (2012). Contrastive knowledge. In M. Blaauw (Ed.), Contrastivism in philosophy (pp. 101–115). Routledge.

Potts, C. (2005). The logic of conventional implicatures. Oxford University Press.

Roberts, C. (2012). Information structure in discourse: Towards an integrated formal theory of pragmatics. Semantics and Pragmatics, 5, 1–69.

Rooth, M. (1985). Association with Focus. PhD thesis, Dept. of Linguistics, University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

Rooth, M. (1992). A theory of focus interpretation. Natural Language Semantics, 1(1), 75–116.

Schaffer, J. (2004). From contextualism to contrastivism. Philosophical Studies, 119(1/2), 73–103.

Schaffer, J. (2005). Contrastive knowledge. In T. S. Gendler & J. Hawthorne (Eds.), Oxford studies in epistemology (Vol. 1, pp. 235–271). Oxford University Press.

Schaffer, J. (2007). Closure, contrast, and answer. Philosophical Studies, 133(2), 233–255.

Schaffer, J. (2007). Knowing the answer. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 75(2), 383–403.

Schaffer, J. (2008). The contrast-sensitivity of knowledge ascriptions. Social Epistemology, 22(3), 235–245.

Schaffer, J. (2009). Knowing the answer redux. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 78(2), 477–500.

Schaffer, J., & Knobe, J. (2012). Contrastive knowledge surveyed. Noûs, 46(4), 675–708.

Schlenker, P. (forthcoming). Supplements without Bidimensionalism. Linguistic Inquiry.

Simons, M., Beaver, D., Roberts, C., & Tonhauser, J. (2017). The best question: Explaining the projection behavior of factives. Discourse Processes, 54(3), 187–206.

Sinnott-Armstrong, W. (2004). Classy pyrrhonism. In W. Sinnott-Armstrong (Ed.), Pyrrhonian skepticism (pp. 188–207). Oxford University Press.

Sinnott-Armstrong, W. (2008). A contrastivist manifesto. Social Epistemology, 22(3), 257–270.

Steglich-Petersen, A. (2014). Knowing the answer to a loaded question. Theoria, 80(1), 97–125.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to two anonymous referees of this journal for their helpful comments on earlier versions of this paper. I also wish to thank Jordan Bell, I-Sen Chen, Rohan French, Natasha Haddal, Hanti Lin, Patrick Skeels, S. Kaan Tabakci, and other members of UC Davis LLEMMMa reading group. Special thanks to Adam Sennet for all the valuable guidance and support.

Funding

Not funded.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Fan, D. From contrastivism back to contextualism. Synthese 201, 13 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-022-04010-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-022-04010-4