Abstract

Despite the pervasive use of ethics training by companies, research in management accounting has not considered the effectiveness of such training in curtailing managers’ misreporting. This study examines the effect of ethics training on misreporting as a reminder to raise the awareness of employees’ ethical commitment. Furthermore, this study investigates the extent to which reciprocity in the workplace affects managers’ misreporting. The results from an experiment involving 124 managers show that in the absence of an ethical commitment reminder, managers are more likely to engage in misreporting than when an ethical commitment reminder is present. The results suggest that ethical commitment reminder interacts with reciprocity in the workplace, affecting managers’ misreporting. Specifically, the results reveal that managers are more likely to engage in misreporting under the reciprocity in the workplace condition when the ethical commitment reminder is absent. The theoretical and practical implications of these findings are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

According to a recent study conducted by the Association of Certified Fraud Examiners (ACFE), there were 2,504 cases of occupational fraud, which accounted for more than US$3.6 billion in total losses in 125 countries across 23 industries categories (ACFE, 2020). ACFE identifies financial statement fraud as one of the most frequently committed occupational frauds. Financial statement fraud involves the perpetrator intentionally omitting or misrepresenting information in the firm’s financial statements. This study focuses on misreporting, which is a type of occupational fraud that is defined as the managers’ action of intentionally withholding or misrepresenting information (Chong & Wang, 2019; Keil & Robey, 2001). Prior studies have suggested that misreporting can lead to negative consequences for an organization (e.g., Choi & Gipper, 2019; Gao & Jia, 2021; Karpoff et al., 2008; Smith et al., 2009).Footnote 1 For example, Smith et al., (2009, p. 577) suggest that “without complete and accurate status information, a project manager’s ability to monitor progress, allocate resources effectively, and detect and respond to problems is greatly diminished, and this can lead to impaired project performance.” Misreporting has attracted increased attention in accounting and other disciplines (e.g., Cardinaels & Jia, 2016; Chong & Wang, 2019; Church et al., 2012, 2014; Free & Murphy, 2015; Hannan et al., 2006; Mass & van Rinsum, 2013; Mayhew & Murphy, 2014). Organizations are now faced with increased pressure to better understand how to design an effective management control system that can deter occupational fraud such as misreporting in organizations (Church et al., 2014; Maas & van Rinsum, 2013; Murphy & Dacin, 2011; Murphy & Free, 2016; Smith et al., 2009). This study aims to extend and contribute to research in this area.

Following major financial scandals in the early 2000s, companies are now under enormous pressure to incorporate ethics codes into their management control systems (Securities and Exchange Commission [SEC], 2003b). For example, Sect. 406 of the Sarbanes–Oxley Act (SOX) contains a fundamental provision about companies’ disclosure of their adoption of a corporate ethics code or a justification of the absence of such a code. Similarly, Recommendation 3.2 of the Corporate Governance Principles and the Recommendations from the ASX Corporate Governance Council (ASX, 2019) indicate that a listed entity in Australia should have and disclose a code of conduct for its directors, senior executives, and employees using an “if not, why not” approach. Following these regulatory requirements, many companies have established a code of conduct for all employees and have socialized the code through ethics training (Singh, 2011). A great deal of research has been conducted to investigate the effectiveness of such codes on companies’ performance. However, the results are mixed (e.g., Helin & Sandström, 2007; Steven, 1994). After reviewing the evidence from the literature, some companies use a code of ethics merely as a “window dressing” to mitigate their legal liability. In addition, research has found that some ethics training programs are often short lived and ineffective (Fraedrich et al., 2005; Richards, 1999; Tenbrunsel & Messick, 2004; Warren et al., 2014) despite these programs being designed to provide ethical-related information that can remind employees of their ethical responsibilities and/or ethical social norms (e.g., “doing the right thing”). To date, there is a lack of empirical evidence on why such programs fail to deter unethical behavior. Therefore, the first motivation of this study is to examine the effectiveness of ethics training programs as reminders that can increase employees’ awareness of their ethical commitments.

Relying on self-concept maintenance theory, this study argues that reminders of ethical-related information help raise managers’ awareness of the importance of social norms, such as a preference for honest managerial reporting (Mazar et al., 2008). Prior research shows that reminders in any form (e.g., written messages) can direct people’s attention to their behavior by activating ethical and social norms and reminding people of their violations of ethical norms (Ayal et al., 2015; Cialdini, 2003). Ayal et al. (2015) propose using reminders as one of the three methods that can change people’s unethical behavior. Ayal et al., (2015, pp. 739–741) state the following about reminders:

…emphasizes the effectiveness of subtle cues that increase the salience of morality and decrease the ability to justify dishonesty. […] Reminding mitigates grey areas that blur the ethical code, visibility mitigates anonymity and the slippery slope of social norms, and the gap between moral values and actual behavior can be reconciled by encouraging self-engagement.Footnote 2

In this study, an ethical commitment reminder refers to the availability of ethical-related information that can be used to direct employees’ attention toward moral standards (Ayal et al., 2015; Mazar et al., 2008). Self-concept maintenance theory suggests that moral reminders can be used to direct people’s attention toward moral standards and enhance honesty (Mazar et al., 2008). Thus, reminder messages can be used to effectively curb dishonest behavior (Grym & Liljander, 2016; Pruckner & Sausgruber, 2013). Research suggests that individuals cannot behave unethically without updating their self-concept when they are reminded of their moral standards (Mazar et al., 2008; Shu et al., 2012).

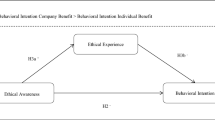

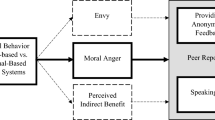

This study adopts a unique setting of a reciprocal relationship between a superior (i.e., a senior manager) and a subordinate (i.e., a superior–subordinate relationship),Footnote 3 and in which a return of a favor that the superior received earlier would require the superior to withhold key information. This reciprocal relationship represents vertical reciprocity in the workplace (see Fig. 1) (Sanders & Schyns, 2006; Sanders et al., 2006; Uhl-Bien & Maslyn, 2003).

While the role of reciprocity in the workplace in employees’ (un)ethical behavior has attracted a great deal of research interest, prior literature in this area generally focuses on the organization–employee relationships (Hannan, 2005) and subordinate–subordinate relationships, that is, horizontal reciprocity in the workplace (e.g., Evans et al., 2016; Zhang, 2008). For example, Evans et al. (2016) demonstrate that nonbinding collusive agreements in an open work environment can lead to misreporting when reciprocation is involved. Furthermore, Zhao et al. (2019) find that reciprocity, workplace ostracism, and moral disengagement are associated with knowledge hiding. Vertical reciprocity in the workplace remains under-researched, yet such relationships are particularly important to examine because they are central to understanding the collusive behaviors between superiors and subordinates (Celik, 2009; Gromb & Martimort, 2007), such as subordinates’ opportunistic misreporting and superiors’ tolerance for subordinates’ misreporting. To fill this gap in the literature, this study relies on social exchange theory and norm of reciprocity theory to examine whether vertical reciprocity in the workplace affects superiors’ decisions to misreport. In the study, reciprocity in the workplace is viewed as a psychological obligation to return a favor a manager received earlier from their subordinate, in which the fulfillment of this obligation would constitute a violation of social norms (i.e., being dishonest). Psychological contracts fall within the domain of social exchange and refer to “an individual’s beliefs regarding reciprocal obligations” (Rosseau, 1990, p. 390). This study expects that the superior would feel obliged to return the earlier favor from the subordinate because of the perceived obligations, expectations, and exchange agreement between the two parties. The study further expects that the use of an ethical commitment reminder can act as a reminder of social norms and give the superior an ethical/reasonable ground to breach the reciprocal relationship with the subordinate without significant punishment, and therefore, deter misreporting.

The study uses a 2 × 2 experimental design where the ethical commitment reminder (absent, present) and reciprocity in the workplace (absent, present) are manipulated between subjects. The participants consist of 124 managers in the United States (US) manufacturing industry recruited through an online research panel, Qualtrics. The experimental setting presented a scenario of a manager in a dilemma in which they had received a favor from a subordinate earlier and returning the favor would require the manager to misreport, which is a violation of social norms. The results reveal that the likelihood of managers’ misreporting is lower when an ethical commitment reminder is present. In addition, the study finds that managers who face a situation of a reciprocal relationship in the workplace are more likely to misreport when an ethical commitment reminder is absent than when it is present. Taken together, these results support the theoretical expectations.

The findings of this study make the following contributions to the literature. First, the study extends prior literature on managerial misreporting (Cardinaels & Jia, 2016; Chong & Wang, 2019; Chung & Hsu, 2017; Maas & Van Rinsum, 2013; Mayhew & Murphy, 2014; Sánchez-Expósito & Naranjo-Gil, 2017). The result reveals that ethical commitment reminders can be an effective preventive control to deter misreporting behavior. Second, the results demonstrate that managers in a reciprocal relationship are more likely to behave dysfunctionally (i.e., to misreport) when an ethical commitment reminder is absent than when an ethical commitment reminder is present. Specifically, the study provides empirical evidence of the dark side effect of vertical reciprocity or superior–subordinate work relationships when an ethical commitment reminder is absent. The results reveal that managers (i.e., superiors) who are obliged to reciprocate are more likely to engage in an unethical action that would benefit the subordinate who helped them before; however, managers make this unethical decision only when the formal control of an ethical commitment reminder is absent. Third, the findings support the validity of relying on multiple theories (e.g., self-concept maintenance theory and social exchange theory) to explain the phenomenon of misreporting (Chong & Eggleton, 2007; Kachelmeier, 1994, 1996; Luft, 1997; Merchant et al., 2003). The study reveals that while the social exchange theory predicts that individuals will misreport, self-concept maintenance theory explains individuals’ actual dishonest behavior and their desire to maintain a positive self-image, and moral disengagement theory suggests that individuals will misbehave “to a tolerable threshold level” (Mayhew & Murphy, 2014, p. 424).

The remainder of this study is organized as follows. The following sections provide the hypotheses development of the study, describe the research method used, and report the results of the data analysis. The last section provides the limitations of the study, implications for practice, and future research.

Hypotheses Development

Ethics Training Programs and Their Role in Battling Occupational Fraud

A social norm is defined as a rule of conduct that determines right and wrong behavior in a given situation (Bicchieri, 2006). According to the social norm theory, individuals prefer to conform to social norms conform to a particular behavior when they know that the specific behavior is relevant in their specific social setting. Bicchieri (2006) suggests that individuals become aware of specific behavior through empirical and normative expectations. Empirical expectations refer to the belief that a substantial number of individuals in the same social setting conform to the same social norms, and normative expectations refer to the belief that most people in the same social setting expect conformance with social norms. In the context of this study, the term “social norm” refers to the company’s code of ethics.

Following major financial scandals, companies are now under enormous pressure to incorporate ethics codes into their management control systems (SEC, 2003b). The establishment of SOX is one factor that has placed pressure on companies in the US to adopt a corporate code of ethics (SEC, 2003a). Section 406 of SOX contains a fundamental provision about companies’ disclosure of their adoption of a corporate ethics code or to provide justification for the absence of such a code. A great deal of research has been conducted to investigate the effectiveness of these codes on companies’ performance. However, the results are mixed (e.g., Helin & Sandström, 2007; Steven, 1994). For example, in their review, Helin and Sandström (2007) conclude that some companies use a code of ethics merely as a “window dressing” to mitigate their legal liability, and Palmer and Zakhem (2001, p. 83) argue that “merely having standards is not enough, a company must make the standards understood, and ensure their proper dissemination within the organizational structure.” Stevens (1994) suggests that it is necessary to communicate an ethical code to ensure its success.

Singh (2011) suggests that to battle occupational fraud, regulators and companies are establishing ethical codes of conduct and using training to socialize these codes of conduct. Valentine and Fleischman (2004) indicate that employees with ethics training have a positive perception of a company’s ethical conduct. Ethics training can enhance employees’ awareness of acceptable business conduct (Izzo, 2000; Loe & Weeks, 2000) and increase employees’ identification of common ethical problems and their problem-solving ability in relation to such problems (Loe & Weeks, 2000; Palmer & Zakhem, 2001). Furthermore, Mayhew and Murphy (2009) find that ethics training can raise individuals’ awareness of ethical problems, thus, enabling them to make better ethical judgments and decisions.

Despite these findings of the positive influence of ethics training, the effectiveness of such training in deterring unethical behavior in the organization is problematic (Booth & Schulz, 2004). Prior studies suggest that most ethics training programs are short lived and ineffective (Fraedrich et al., 2005; Kaptein, 2011; Richards, 1999; Tenbrunsel & Messick, 2004; Warren et al., 2014). Research finds that one way to enhance the effectiveness of ethics training is to use reminders as a tool (Bicchieri, 2006; Mazar et al., 2008) that will regularly remind employees of their ethical commitments. Following this proposition, this study examines the effect of an ethical commitment reminder on misreporting behavior.

Ethical Commitment Reminder

It has been suggested that a reminder can act as a situational cue, which, according to social norm theory (Bicchieri, 2006), can increase individuals’ empirical and/or normative expectations of a social norm. These situational cues lead individuals to believe that certain norms and behaviors are appropriate to implement in a specific social setting. The present study argues that an ethical commitment reminder can act as a situational cue that increases individuals’ empirical and/or normative expectations of the company’s code of ethics. In the study setting, the ethical commitment reminder is operationalized as an annual online module test of the company’s code of ethics.Footnote 4 Giving a reminder in any form can activate individuals’ social norms and make them aware that they should not violate those norms (Cai et al., 2015; Cialdini, 2003), therefore, the obligation to take the annual online module test of their company’s code of ethics could lead employees to believe that all employees are expected to conform to behavior that follows the company’s code of ethics. It is expected that an ethical commitment reminder will activate the social norms by increasing the normative expectations of the employees. A regular ethical commitment reminder (e.g., on an annual basis) can also send an implicit message to employees about what their company is asking them to do.Footnote 5

Following the self-concept maintenance theory, this study further proposes that an ethical commitment reminder can make individuals update their positive self-concept, resulting in lowering individuals’ unethical behavior thresholds. Mazar et al. (2008) find that people will engage in misreporting to the extent that their action does not hurt their self-concept (e.g., feeling guilty), suggesting that individuals have a threshold for engaging in misreporting. The self-concept maintenance theory posits that this threshold can be lowered by introducing an “attention to standards,” which refers to individuals’ attention to their standards of conduct (Mazar et al., 2008). When individuals pay more attention to established standards, they update their positive self-concept, lower their unethical/opportunistic behavior threshold, and are discouraged from acting dishonestly (Mazar et al., 2008). Thus, in the context of this study, it is expected that when employees are reminded to consider the standards of conduct, they will be reminded of their ethical commitments and update their positive self-concept. Subsequently, the updated positive self-concept will make their misreporting threshold lower and, in turn, reduce their misreporting behavior. Thus, an ethical commitment reminder is expected to activate employees’ social norms and update their positive self-concept, thus, discouraging them from misreporting. The study expects that superiors are less likely to engage in misreporting when an ethical commitment reminder is present than when it is absent. This leads to the following hypothesis:

H1

Superiors are less likely to engage in misreporting when an ethical commitment reminder is present than when an ethical commitment reminder is absent.

Reciprocity in the Workplace

Reciprocity, in general, refers to the action of repaying another person’s action with a similar action (Gouldner, 1960). Gouldner (1960) uses the term “reciprocity” to explain the return of kindness with kindness and uses the term “retaliation” for returning unkindness with unkindness. Reciprocity is also a key characteristic of a psychological contract between two parties. Rousseau (1989, p. 123) defines a psychological contract as follows:

an individual’s beliefs regarding the terms and conditions of a reciprocal exchange agreement between that focal person and another party. Key issues here include the belief that a promise has been made and a consideration offered in exchange for it, binding the parties to some set of reciprocal obligations.

Unlike a legal contract, a psychological contract is often considered to refer to an individual’s beliefs about an ongoing exchange relationship with another party, and these beliefs are implicit and subjective, and they are based on a perceived agreement rather than actual agreement (Conway & Briner, 2005). The ongoingness of the exchange implies that each party will fulfill its promises to the other party in repeated cycles. Therefore, each party is bound to a set of reciprocal obligations in which any favor has done by an individual for others will be repaid in the future (Blau, 1964; Gouldner, 1960).

Prior literature finds that there are many benefits associated with reciprocity in an organization (e.g.Deckop et al., 2003; Hannan, 2005; Kuang & Moser, 2009; Levinson, 2009; Maitland et al., 1985; Sama & Shoaf, 2008; Shore & Wayne, 1993). For example, accounting finds that reciprocity can be used to complement classic agency contracts in an organizational setting. Hannan (2005) demonstrates that paying higher wages to employees makes them exert greater effort in their work roles. Similarly, Kuang and Moser (2009) find that employees respond to wages offered by the firm above the market level by exerting more effort. Thus, reciprocity can be used to benefit the firm and its employees. Furthermore, Deckop et al. (2003) reveal that employees show more helping behavior after receiving good organizational citizenship behavior from co-workers. In addition, Sama and Shoaf (2008) indicate that reciprocity can foster trust and help in creating a moral community among professionals.

Despite its positive effect, reciprocity also has a potential dark side (e.g.Abbink et al., 2002; Tangpong et al., 2016). Reciprocity exerts pressure on individuals that makes them feel obligated to return a favor to others (Tangpong et al., 2016). Tangpong et al. (2016) demonstrate that individuals who are in reciprocal relationships are inclined to contemplate a questionable or even unacceptable ethical decision. For example, the participants in Abbink et al. (2002) reciprocate in a bribery relationship at a cost to others. Thus, although reciprocity can be beneficial to parties in a reciprocal relationship, it can have an adverse effect on individuals who are not in the reciprocal relationship.

While prior literature on reciprocity in the workplace generally focuses on the reciprocal relationships between the organization and its employees (e.g., Hannan, 2005) and among co-workers (e.g., Tangpong et al., 2016), this study examines the reciprocal relationship between the superior and their subordinates, that is, vertical reciprocity in the workplace. This relationship is particularly important to examine because it is central to understanding the collusive behaviors of superiors and subordinates (Celik, 2009; Gromb & Martimort, 2007), for example, subordinates’ opportunistic misreporting and superiors’ tolerance for subordinates’ misreporting.

In this study, reciprocity in the workplace refers to a psychological obligation to return a favor that a superior received earlier from their subordinate in the context that the fulfillment of this obligation would constitute a violation of social norms. Specifically, in the experimental setting, superiors are placed in a dilemma where they received favor from a subordinate earlier and the return of this favor would require the superior to misreport, which is a violation of a social norm. Following the idea of psychological contracts, it would be expected that the superior would feel obliged to return the earlier favor from the subordinate under the perceived exchange agreement between the two parties despite this action constituting misreporting. Thus, it is expected when superiors are in a reciprocal relationship, they are more likely to engage in misreporting to return a favor than are superiors who are not in a reciprocal relationship. This leads to the following hypothesis:

H2

Superiors are more likely to engage in misreporting when reciprocity in the workplace is present than when reciprocity in the workplace is absent.

The Interaction Effect

In line with the discussion presented above, the negative effect of an ethical commitment reminder on the manager’s misreporting may be contingent on the presence of a reciprocal relationship between the superior and the superior’s subordinates. This study proposes this negative effect is greater when a reciprocal relationship is present because the presence of such a relationship can lead to pressure to violate social norms. As stated, a reciprocal relationship between a superior and a subordinate can be considered a psychological contract. However, a psychological contract is not as powerful as a legal contract (Conway & Briner, 2005). Its characteristics such as implicitness, non-mutuality, and subjectivity can make it easier for a supervisor to justify their decision to breach such a contract without significant punishment (from the other party). In the current context, this study expects that the presence of an ethical commitment reminder acts as a reminder of the social norm and gives the manager an ethical/reasonable ground to breach such a psychological contract without significant punishment from the subordinate. Therefore, the superior is less likely to misreport than when an ethical commitment reminder is absent.

In contrast, when the reciprocal relationship between the superior and subordinate is absent, ceteris paribus, the effect of an ethical commitment reminder will be less important in reducing the likelihood of the manager engaging in misreporting because no violation of social norms will be observed. This study predicts an ordinal interaction (Jaccard, 2004) where the gap in the likelihood of a superior’s misreporting between ethical commitment reminder present and absent (as predicted in H1) is greater when a reciprocal relationship is present between the superior and their subordinate than when this reciprocal relationship is absent. This leads to the following hypothesis:

H3

The difference in the likelihood of the superior engaging in misreporting when an ethical commitment reminder is present or absent is expected to be greater when reciprocity in the workplace is present than when reciprocity in the workplace is absent (i.e., [Cell 2 – Cell 4] > [Cell 1 – Cell 3]; see Fig. 2).

Research Method

Participants and Administration

A large international online research panel, Qualtrics, was used to collect the data for this study. From 2000 to 2012, there was an increasing trend in the use of online-based services to recruit participants (Brandon et al., 2014), and many researchers have supported the use of online survey platforms such as Qualtrics (e.g., Brandon et al., 2014; Croteau et al., 2010; Holt & Loraas, 2019). For example, Croteau et al. (2010) suggest that the response and data quality resulting from online surveys do not differ from those yielded using traditional paper-based surveys. Holt and Loraas (2019) highlight two appealing aspects of using online survey platforms such as Qualtrics: (1) participation is truly voluntary, and (2) participants are truly anonymous to the researcher. Prior accounting studies (Long & Basoglu, 2016; Nelson & Rupar, 2015) have used the Qualtrics panel to recruit their participants.

Qualtrics distributed the invitation letters for our study and the research instrument to its online research panel members.Footnote 6 The participants in this study were managers in the US manufacturing industry. The following criteria were used for sample inclusion. First, the participants must be above 18 years old. Second, the participants must be working in a manufacturing company. Third, the participants must be managers with at least two years of experience (to ensure that managers had sufficient experience in making decisions). Fourth, the company must have more than 100 employees (to ensure that the company has an adequate accounting system and to enable the study to control for company size). Fifth, the participants must have at least one employee under their direct supervision.

A total of 386 panel members qualified for the study.Footnote 7 Of these 386, a total of 226 panel members did not respond or did not complete their responses, resulting in 160 panel members participating in the study, which provided a response rate of 41.45%. An examination of the participants’ internet protocol addresses revealed six identical addresses, and these participants were excluded from the data. Thirty participants failed the manipulation check questions. Thus, the final sample consisted of 124 participants, resulting in a usable rate of 77.5%.

Table 1 presents the demographic information of the sample. As presented in the table, the participants have held their current position for an average of 9.20 years and have been employed by their current employer for an average of 12.67 years. The participants are 46 (37.10%) females and 78 (62.90%) males. The average age of the participants is 45 years old. The participants are widely spread across different sectors in the manufacturing industry and have held managerial positions in various departments.

Experimental Task and Design

This study developed a case scenario for this study. The participants were asked to read the case scenario including background information about a profit center division of a hypothetical large wood company and the divisional sales and operating costs, which were held constant across treatments. Participants then read the information about the ethical commitment reminder and reciprocity in the workplace in accordance with the experimental treatment that they were assigned. Participants then answered a series of questions used to test the study’s hypotheses before responding to the manipulation check and demographic questions.

This study used a 2 × 2 between-subjects research design to test the hypotheses. The study manipulated the presence of an ethical commitment reminder (absent or present) and reciprocity in the workplace (absent or present). The case described a scenario in which the subsidiary general manager (GM) (named Kim Green) was reviewing sales and operating cost reports before submitting them to the head office, and the reports showed that the business unit (BU), “Glam,” had exceeded its profit target. The GM (i.e., the superior) also heard a rumor from a fellow GM in the same industry about a new laboratory test that could determine any flaws in specific wood material. The GM knew that most of the subsidiary’s material inventory consisted of this specific wood material and wondered whether to instruct the warehouse manager to conduct this laboratory test. The GM realized that if the authorization for the investigation of the inventory was given and flaws in the wood material were found, then a significant amount of the inventory would have to be written off. As a result of the inventory write-off, the BU’s profit would be reduced, and the profit target would not be met. As a result, BU’s employees would not receive any bonuses. However, the GM’s bonus would not be affected because their bonus would be calculated based on the growth of the BU’s market share.

The dependent variable of this study is the GM’s likelihood of misreporting, which is primarily measured by asking participants to assess on a 10-point scale how likely it is that the GM would instruct the warehouse manager to conduct the laboratory test on the inventory. Given the current design, a lower likelihood of conducting the laboratory test would suggest a higher likelihood of the GM misreporting the inventory valuation.Footnote 8 To make the interpretation of the results easier to understand, the original response scores were reversed. That is, a higher score suggests a higher likelihood of GM misreporting.

The first independent variable is the presence of an ethical commitment reminder. This study manipulates this variable at two levels: present versus absent. In the treatments where an ethical commitment reminder was present, participants were told the following:

Carpenter has an established code of ethics. The purpose of the code of ethics is to promote the honest and ethical conduct of all board members, senior executives, general managers, and all other employees of Carpenter, including accurate, timely, and understandable disclosure in periodic reports. All employees in Carpenter sign a statement that they will comply with the code of ethics.

As one of the annual performance evaluation requirements, the company requires all employees to take and pass an online module test of the company’s code of ethics every year.

In contrast, in the treatments where the ethical commitment reminder was absent, participants read-only general information about the company’s code of ethics and were told that every employee signed a statement that they would comply with the company’s code of ethics.

The second independent variable is the presence of reciprocity in the workplace, which is manipulated at two levels: present versus absent. As stated, this study focuses on the vertical reciprocal relationship between a superior and a subordinate. In the treatments where reciprocity in the workplace was present, participants were given general information about the harmonious working conditions in the Glam subsidiary, where everyone was willing to help each other not only with work but also with family matters; after that, participants read the following information:

There was one occasion in 2018 during the family gathering, where Kim had a chat with Glam’s warehouse manager. The warehouse manager told Kim about her/his family’s plan to have a trip across Europe if the bonus was achieved. The warehouse manager added that her/his family was so excited and looking forward to the trip. Furthermore, Kim talked about the plan for her/his child to enroll in a very prestigious school in the city, which had a very competitive enrollment process. The warehouse manager then called her/his spouse, who was a member of the school committee at that school, and told her/him about Kim’s plan of enrolling her/his child in the school. The warehouse manager’s spouse told Kim not to worry too much and wished the family good luck. When the school enrollment was announced, Kim was delighted to find that her/his child had been accepted into that prestigious school.

In contrast, participants in the treatments where reciprocity in the workplace was absent read general information about the harmonious working condition in the Glam subsidiary, where everyone was willing to help each other not only with work matters but also with family matters.

The experimental instrument was pre-tested in a separate group of 16 participants from an online research panel provided by Qualtrics. The pilot test showed variance in the dependent variable, and that variance could be explained by the independent variables in this study. The experimental case was randomly distributed by Qualtrics using a randomizer function in its survey software. The randomizer tool ensures that participants will receive one out of the four experimental cases by chance.

Results

Manipulation Checks

Manipulation checks test whether participants understand the manipulation of the variables in an experimental design (Hoewe, 2017). Failure to answer the manipulation check questions correctly reduces the internal validity of the experiment. Two questions were used to check whether the participants understood the conditions in the experimental case. The first question asked the participants whether Kim Green had a chat with Glam’s warehouse manager about her/his plan to enroll her/his child in a prestigious school in the city. The second question asked whether every year the Carpenter company requires all employees to take and pass an online module test of Carpenter’s code of ethics as one of its annual performance evaluation requirements. Of the 160 participants who completed the online research instrument, 30 failed to correctly answer the manipulation check questions.Footnote 9 These were excluded from the data.Footnote 10

Test of Hypotheses

H1 predicts that superiors are less likely to engage in misreporting when an ethical commitment reminder is present than when an ethical commitment reminder is absent. The results of the analysis of variance (ANOVA) reported in Table 2 and Fig. 3 are consistent with this study’s expectations. The assessed likelihood of the superior misreporting is higher when an ethical commitment reminder is absent (5.815) than when an ethical commitment reminder is present (4.414) (Table 2, Panel B) and this difference is significant (F = 6.053, p = 0.015; Table 2, Panel A). Therefore, H1 is supported.

Figure 3 demonstrates this finding where the means for the ethical commitment reminder is absent are 5.440 (i.e., when reciprocity in the workplace is absent), and 6.138 (i.e., when reciprocity in the workplace is present); while the means for ethical commitment reminder is present are 4.429 (i.e., when reciprocity in the workplace is absent) and 4.400 (i.e., when reciprocity in the workplace is present).

H2 predicts that superiors are more likely to engage in misreporting when reciprocity in the workplace is present than when reciprocity in the workplace is absent. The result indicates that the main effect of reciprocity in the workplace (F = 0.359, p = 0.550; Table 2, Panel A) is not statistically significant. Thus, H2 is not supported.

H3 states that the difference in the likelihood of the superior engaging in misreporting when an ethical commitment reminder is present or absent is expected to be greater when reciprocity in the workplace is present than when reciprocity in the workplace is absent (i.e., [Cell 2 – Cell 4] > [Cell 1 – Cell 3], Fig. 2). The results from Table 2 Panel A reveal that the interaction between ethical commitment reminder and reciprocity in the workplace (F = 0.423, p = 0.517) is not statistically significant. Furthermore, the descriptive statistics (Table 2, Panel B) show that consistent with the expectations in H3, the effect of ethical commitment reminder on the likelihood of a superior misreporting is significant only when there is a reciprocal relationship between the superior and the subordinate (F = 5.049, p = 0.026).

Figure 3 demonstrates an ordinal interaction, which is consistent with the study’s hypothesis, as the gap between the ethical commitment reminder present and ethical commitment reminder absent lines is greater when reciprocity is present than when reciprocity is absent. To test H3, Panel C in Table 2 includes a contrast that has custom weights (Buckless & Ravenscroft, 1990) for Cell 1 (ethical commitment reminder absent, reciprocity absent); Cell 2 (ethical commitment reminder absent, reciprocity present); Cell 3 (ethical commitment reminder present, reciprocity absent); and Cell 4 (ethical commitment reminder present, reciprocity present): [+ 0.5, + 2, − 1.5, − 1]. This pattern is consistent with the study’s prediction that the difference in the likelihood of the superior engaging in misreporting when an ethical commitment reminder is present or absent is greater when reciprocity in the workplace is present than when reciprocity in the workplace is absent, meaning that (Cell 2 – Cell 4) is greater than (Cell 1 – Cell 3). This contrast coding is also consistent with the predictions that the likelihood of the superior engaging in misreporting is higher when an ethical commitment reminder is absent than when an ethical commitment reminder is present (Cell 1 > Cell 3 and Cell 2 > Cell 4, H1), and the likelihood of the superior engaging in misreporting is higher when reciprocity is present than when reciprocity is absent (Cell 2 > Cell 1 and Cell 4 > Cell 3, H2). Following the recommendations of Guggenmos et al. (2018), this study reports the test of the contrasts, residual between-cells variance, and total between-cells variance. The contrast is significant (F = 6.840, p = 0.010; Table 2, Panel C). In addition, the contrast variance residual is 0.022, suggesting that only 2.20% of the between-cells variance is not explained by the contrast test. That is, this study’s hypothesized contrast explains approximately 97.80% of the between-cell variance. Taken together, these results support H3.

Conclusion

This study examines whether the presence of an ethical commitment reminder and the presence of reciprocity in the workplace independently and jointly influence superiors’ misreporting. Specifically, the study examines whether an ethical commitment reminder in the form of annual ethics training can deter superiors’ misreporting. The results of this study are consistent with the prediction that the manager is less likely to misreport when an ethical commitment reminder is present than when an ethical commitment reminder is absent.

This study also examines whether a reciprocal relationship between a superior and their subordinate provides an opportunity for the superior to engage in misreporting. The study predicts that a superior will be more likely to choose not to report a possible flaw when the superior is in a reciprocal relationship in which they feel obligated to return an earlier favor from a subordinate than when the superior is not in a reciprocal relationship. The result for this prediction is not supported.

The interaction effect of ethical commitment reminder and reciprocity in the workplace on superiors’ misreporting behavior is also examined. The study proposes that the deterrence effect of using an ethical commitment reminder is greater when a reciprocal relationship between the superior and the subordinate is present because the presence of such a relationship can lead to a violation of the social norms. The results of the study show that the gap in the likelihood of the manager engaging in misreporting when an ethical commitment reminder is present or absent is greater when a reciprocal relationship between the superior and their subordinate is present than when this reciprocal relationship is absent. This finding is consistent with the prediction that the use of an ethical commitment reminder acts as a reminder of the social norm and gives the superior an ethical/reasonable ground to breach the reciprocal relationship with the subordinate without significant punishment.

This study makes the following contributions. First, the results of the study provide empirical evidence of the effectiveness of the use of an ethical commitment reminder to curb misreporting. This study’s findings respond to the call for further investigation of how a strong ethical environment can affect a manager’s ethical decisions (Booth & Schulz, 2004). The findings of this study demonstrate that ethical commitment reminder can be an effective management control to deter misreporting and adds to the stream of studies that examine factors that can be used to deter misreporting behavior (Cardinaels & Jia, 2016; Chong & Wang, 2019; Chung & Hsu, 2017; Maas & Van Rinsum, 2013; Sánchez-Expósito & Naranjo-Gil, 2017).

Second, this study empirically examines a unique setting where there is a reciprocal relationship between a superior and their subordinate. While prior literature examining the effect of reciprocity on (un)ethical behavior generally focuses on the reciprocal relationship between an organization and its employees and among co-workers, this study examines the potential dark side of reciprocity by examining a vertical reciprocal relationship, in which a superior has a psychological obligation to return a favor they received earlier from a subordinate in a situation where the fulfillment of that obligation would constitute a violation of a social norm (i.e., misreporting). However, the study does not find there is a statistically significant main effect of vertical reciprocity on superiors’ reporting, suggesting that vertical reciprocity in the workplace is not present. This study provides the following plausible explanation. According to the self-concept maintenance theory (see Mazar et al., 2008, p. 634), people “are often torn between two competing motivations: gaining from cheating versus maintaining a positive self-concept as honest … This seems to be a win-lose situation, such that choosing one path involves sacrificing the other.” In this study’s experimental setting, the superiors may feel that the trade-off involved in the potential gain/benefit they would receive from the employee if returning the favor would be far less important than the potential damage to their reputation as honest managers when withholding information in managerial reporting. That is, the superiors choose not to engage in an unethical act (i.e., to misreport) because the perceived gain from misreporting is much smaller than the perceived loss.

Third, the results for the ordinal interaction reveal that when an ethical commitment reminder is absent, superiors are more likely to misreport when there is a reciprocal relationship between the superior and their subordinate than when such a relationship is absent. This is because an ethical commitment reminder can make individuals update their positive self-concept, resulting in lowering individuals’ unethical behavior thresholds as predicted by the self-concept maintenance theory (Mazar et al., 2008). This finding is consistent with Mayhew and Murphy (2014, p. 424), who rely on moral disengagement theory (Bandura, 1990, 1999; Bandura et al., 1996) and conclude that “it is more likely that individuals experience negative affect on a continuum where the decision to misbehave does not depend on reducing ex-post negative affect to zero but to a tolerable threshold level.” The study’s findings provide support for the validity of relying on multiple theories (e.g., self-concept maintenance theory and social exchange theory) to explain the misreporting phenomenon (Chong & Eggleton, 2007; Kachelmeier, 1994, 1996; Luft, 1997; Merchant et al., 2003).

The results of this study have important practical implications. First, while an organization should promote positive interpersonal relationships among its employees, such as helping others and accepting additional responsibilities (Bolino et al., 2013; Organ et al., 2006), the study’s findings suggest that organizations should also remain cautious when attempting to build social ties among employees because the reciprocal nature of these social ties may lead to collusion among employees that can negatively affect effort and performance (Hannan et al., 2013; Maas & Yin, 2022; Zhang, 2008).

Second, the findings of the study suggest that ethical commitment reminders can be used as an effective monitoring control tool to deter misreporting. The results provide support to prior studies that also find the use of reminders can reduce the incidence of unethical behaviors (e.g., cheating) (Mazar et al., 2008; Shariff & Norenzayan, 2007). The findings also add to the extant literature arguing that monitoring controls reduce individuals’ unethical behaviors (Alge et al., 2006; Belle & Cantarelli, 2017; Mazar et al., 2008; Ploner & Regner, 2013; Rixom & Mishra, 2014; Welsh & Ordóñez, 2014). For example, Belle and Cantarelli (2017) conclude that effective monitoring control can reduce an individual’s unethical behavior intentions because it raises the awareness of the individual’s moral standards and promotes self-awareness. The findings of the present study add to such literature by relying on the self-concept maintenance theory to suggest that an ethical commitment reminder helps to draw the employees’ attention to their moral standards and encourage self-awareness. In addition, the finding that the deterrence effect of using an ethical commitment reminder is greater when a reciprocal relationship between a superior and their subordinate is present than when such a relationship is absent highlights this important role of ethical commitment reminders, particularly when a superior faces an ethical dilemma. Companies can benefit from establishing continuous ethics training (e.g., annually) that serves as an ethical commitment reminder for employees to trigger their attention to their moral standards, subsequently updating their positive self-concept and lifting the misreporting threshold.

Third, the results of this study suggest there may be a natural tension between the effects of ethical commitment reminders (i.e., a formal control) and psychological contracts of employees (i.e., reciprocity in the workplace). Thus, it is important to reduce the opportunity to engage in misreporting through the presence of formal controls to weaken the psychological contracts between individuals that would lead to engaging in unethical behavior to return a favor. The insight into these two opposing forces provided by this study can contribute to ensuring the use of effective management controls to deter misreporting.

This study has the following limitations. First, participants in the study are selected from middle-level managers in the manufacturing industry. Thus, the results can be generalized only to similar types of organizations and levels of management. Second, the study uses an experimental design to examine the effect of ethical commitment reminders and reciprocity in the workplace on managers’ misreporting behavior. While the experimental case is designed to be a surrogate of a real-world situation, it reflects a simplified decision-making process that may not have captured all the variables in the real-world business environment. Thus, despite the likelihood of high internal validity because of the use of experimental design, which allows examination of the decision-making process in a controlled environment, caution should be exercised when generalizing the results to different situations. Future research could use a field study to explore the variables used in this study. Third, this study examines employees’ unethical behavior only for relationships of vertical reciprocity in the workplace (i.e., superior–subordinate relationships), future studies should explore this issue for relationships of horizontal reciprocity in the workplace (i.e., subordinate–subordinate relationships).

Notes

According to Ayal et al., (2015, p. 738), self-engagement can increase an individual’s “motivation to maintain a positive self-perception as a moral person and help bridge the gap between moral values and actual behavior.”.

Companies should mandate their employees to sign a certificate to demonstrate that they acknowledge the ethics code and will comply with it. A survey has found that 31% of ethics codes implemented by companies included a signature of acknowledgment (Orin, 2008).

Newman (2014) demonstrates that managers react to a firm’s signal in a form of informal preference about cost targets by reporting a more honest budget.

Qualtrics provides a small monetary incentive to its panel members.

To identify “qualified” panel members for the research project, Qualtrics used a screening process to ensure that the final sample included only qualified panel members. Respondents entering the survey but failing to meet the sample specification’s screening questions were excluded from the system. The Qualtrics online system screened these responses, and they did not count toward the final sample. The “unqualified” respondents are not considered non-respondents. Qualtrics distributed the case material to 2,736 of its online panel members residing in the US. The screening process resulted in 2,350 unqualified participants being dropped, leaving 386 panel members qualified for the study.

The case scenario adopts a third-person perspective, namely, participants were asked to assess the likelihood of the GM acting in a certain way in the case. Third-person scenarios are commonly used in auditing research (e.g., Arnold & Ponemon, 1991; Ponemon & Gabhart, 1990) and in reduced audit quality research (e.g., Coram et al., 2004) to desensitize participants and avoid social desirability response bias. In response to the potential differences between the first-person versus the third-person perspective, this study asked participants to make the same decision assuming they were in the same situation as the GM. The results suggest that participants’ responses to the question were not statistically different when taking a first-person versus third-person perspective. The study follows the approach undertaken by Koh et al. (2018) by measuring the likelihood of misreporting first from the third person’s (i.e., Kim Green’s) perspective and then in the first person’s (i.e., the respondent’s) perspective. The questions were asked in this order to control for social desirability response biases (e.g., Bay & Nitkitkov, 2011; Curtis, 2006; Koh et al., 2011; Pauls & Stemmler, 2003; Trevino, 1992). The use of third-person responses reduces the likelihood of obtaining misleading responses from participants who may not reveal their true intention to misreport when asked to respond from the first-person perspective (Curtis, 2006; Koh et el., 2011; Pauls & Stemmler, 2003). The results of the study demonstrate that the likelihood of misreporting answered from the first-person perspective is significantly lower than the likelihood of misreporting answered from the third-person perspective, hence, the responses from the first-person perspective are dropped from further analysis because they are considered tainted by social desirability response bias.

Specifically, six participants failed to answer the first manipulation check question correctly, 23 participants failed to answer the second manipulation question correctly, and one participant failed to answer both questions correctly.

To test the robustness of the results to the exclusion of the responses that failed the manipulation, this study conducted an ANOVA by including these responses in the analysis (n = 160). The results consistently showed significant main effects of the ethical commitment reminder on the GM’s likelihood of misreporting. However, the effects of reciprocity in the workplace and the interaction effect were not significant.

References

ACFE [Association of Certified Fraud Examiners] (2020). The report to the nation. Retrieved from https://acfepublic.s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/2020-Report-to-the-Nations.pdf

Abbink, K., Irlenbusch, B., & Renner, E. (2002). An experimental bribery game. The Journal of Law, Economics, and Organisation, 18(2), 428–454.

Alge, B. J., Greenberg, J., & Brinsfield, C. T. (2006). An identity-based model of organisational monitoring: Integrating information privacy and organisational justice. In Research in Personnel and Human Resources Management. Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Arnold, D. F., & Ponemon, L. A. (1991). Internal auditors’ perceptions of whistle-blowing and the influence of moral reasoning: An experiment. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 10(2), 1–15.

ASX (2019). Corporate Governance Principles and Recommendations. 4th Edition. February 2019. https://www.asx.com.au/documents/asx-compliance/cgc-principles-and-recommendations-fourth-edn.pdf. Accessed 27 May 2022.

Ayal, S., Gino, F., Barkan, R., & Ariely, D. (2015). Three principles to revise people’s unethical behaviour. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10(6), 738–741.

Bandura, A. (1990). Selective activation and disengagement of moral control. Journal of Social Issues, 46(1), 27–46.

Bandura, A. (1999). Moral disengagement in the perpetration of inhumanities. Personnel and Social Psychology Review, 3(3), 193–209.

Bandura, A., Barbaranaelli, C., Caprara, G. V., & Pastorelli, C. (1996). Mechanisms of moral disengagement in the exercise of moral agency. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71(2), 364–374.

Bay, D., & Nikitkov, A. (2011). Subjective probability assessments of the incidence of unethical behaviour: The importance of scenario–respondent fit. Business Ethics: A European Review, 20(1), 1–11.

Bellé, N., & Cantarelli, P. (2017). What causes unethical behaviour? A meta-analysis to set an agenda for public administration research. Public Administration Review, 77(3), 327–339.

Bicchieri, C. (2006). The Grammar of Society: The Nature and Dynamics of Social Norms. Cambridge University Press.

Blau, P. M. (1964). Exchange and Power in Social Life. John Wiley.

Bolino, M. C., Klotz, A. C., Turnley, W. H., & Harvey, J. (2013). Exploring the dark side of organisational citizenship behaviour. Journal of Organisational Behaviour, 34(4), 542–559.

Booth, P., & Schulz, A. K. D. (2004). The impact of an ethical environment on managers’ project evaluation judgments under agency problem conditions. Accounting, Organisations and Society, 29(5), 473–488.

Brandon, D. M., Long, J. H., Loraas, T. M., Mueller-Phillips, J., & Vansant, B. (2014). Online instrument delivery and participant recruitment services: Emerging opportunities for behavioural accounting research. Behavioural Research in Accounting, 26(1), 1–23.

Buckless, F. A., & Ravenscroft, S. P. (1990). Contrast coding: A refinement of ANOVA in behavioural analysis. The Accounting Review, 65(4), 933–945.

Burt, I., Libby, T., & Presslee, A. (2020). The impact of superior-subordinate identity and ex-post discretionary goal adjustment on subordinate expectancy of reward and performance. Journal of Management Accounting Research, 32(1), 31–49.

Cai, W., Huang, X., Wu, S., & Kou, Y. (2015). Dishonest behaviour is not affected by an image of watching eyes. Evolution and Human Behaviour, 36(2), 110–116.

Cardinaels, E., & Jia, Y. (2016). How audits moderate the effects of incentives and peer behaviour on misreporting. European Accounting Review, 25(1), 183–204.

Celik, G. (2009). Mechanism design with collusive supervision. Journal of Economic Theory, 144(1), 69–95.

Cialdini, R. B. (2003). Crafting normative messages to protect the environment. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 12(4), 105–109.

Choi, J. H., & Gipper, B (2019). Fraudulent financial reporting and the consequences for employees. Working paper, Stanford University. http://128.171.57.22/bitstream/10125/64793/HARC_2020_paper_26.pdf

Chong, V. K., & Eggleton, I. R. C. (2007). The impact of reliance on incentive-based compensation schemes, information asymmetry, and organisational commitment on managerial performance. Management Accounting Research, 18(3), 312–342.

Chong, V. K., & Wang, I. Z. (2019). Delegation of decision rights and misreporting: The roles of incentive-based compensation schemes and responsibility rationalization. European Accounting Review, 28(2), 275–307.

Chung, J. O. Y., & Hsu, S. H. (2017). The effect of cognitive moral development on honesty in managerial reporting. Journal of Business Ethics, 145(3), 563–575.

Church, B. K., Hannan, R. L., & Kuang, X. (2012). Shared interest and honesty in budget reporting. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 37, 155–167.

Church, B. K., Hannan, R. L., & Kuang, X. (2014). Information acquisition and opportunistic behavior in managerial reporting. Contemporary Accounting Research, 31(2), 398–419.

Conway, N., & Briner, R. B. (2005). Understanding psychological contracts at work: A critical evaluation of theory and research. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Coram, P., Ng, J., & Woodliff, D. R. (2004). The effect of risk of misstatement on the propensity to commit reduced audit quality acts under time budget pressure. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 23(2), 159–167.

Croteau, A., Dyer, L., & Miguel, M. (2010). Employee reactions to paper and electronic surveys: An experimental comparison. IEEE Transaction on Professional Communication, 53(3), 249–259.

Curtis, M. B. (2006). Are audit-related ethical decisions dependent upon mood? Journal of Business Ethics, 68(2), 191–209.

Deckop, J. R., Cirka, C. C., & Andersson, L. M. (2003). Doing unto others: The reciprocity of helping behaviour in organisations. Journal of Business Ethics, 47(2), 101–113.

Evans, J. H., III., Moser, D. V., Newman, A. H., & Stikeleather, B. R. (2016). Honor among thieves: Open internal reporting and managerial collusion. Contemporary Accounting Research, 33(4), 1375–1402.

Fraedrich, J., Cherry, J., King, J., & Guo, C. (2005). An empirical investigation of the effects of business ethics training. Marketing Education Review, 15(3), 27–35.

Free, C., & Murphy, P. R. (2015). The ties that bind: The decision to co-offend in fraud. Contemporary Accounting Research, 32(1), 18–54.

Gao, X., & Jia, Y. (2021). The economic consequences of financial misreporting: Evidence from employee perspective. Journal of Management Accounting Research, 33(3), 55–76.

Gouldner, A. W. (1960). The norm of reciprocity: A preliminary statement. American Sociological Review, 25(2), 161–178.

Gromb, D., & Martimort, D. (2007). Collusion and the organisation of delegated expertise. Journal of Economic Theory, 137(1), 271–299.

Grym, J., & Liljander, V. (2016). To cheat or not to cheat? The effect of a moral reminder on cheating. Nordic Journal of Business, 65(3–4), 18–37.

Guggenmos, R. D., Piercey, M. D., & Agoglia, C. P. (2018). Custom contrast testing: Current trends and a new approach. The Accounting Review, 93(5), 223–244.

Hannan, R. L. (2005). The combined effect of wages and firm profit on employee effort. The Accounting Review, 80(1), 167–188.

Hannan, R. L., Rankin, F. W., & Towry, K. L. (2006). The effect of information systems on honesty in managerial reporting: A behavioral perspective. Contemporary Accounting Review, 23(4), 885–918.

Hannan, R. L., Towry, K. L., & Zhang, Y. (2013). Turning up the volume: An experimental investigation of the role of mutual monitoring in tournaments. Contemporary Accounting Research, 30(4), 1401–1426.

Helin, S., & Sandström, J. (2007). An inquiry into the study of corporate codes of ethics. Journal of Business Ethics, 75(3), 253–271.

Hoewe, J. (2017). Manipulation Check. In Matthes J., Davis C. S., & Potter R. F. (Eds.), The International Encyclopedia of Communication Research Methods.

Holt, T. P., & Loraas, T. M. (2019). Using Qualtrics panels to source external auditors: A replication study. Journal of Information Systems, 33(1), 29–41.

Izzo, G. (2000). Compulsory ethics education and the cognitive moral development of salespeople: A quasi-experimental assessment. Journal of Business Ethics, 28(3), 223–241.

Jaccard, J. J. (2004). Ordinal interaction. In M. S. Lewis-Beck, A. Bryman, & T. F. Liao (Eds.), The SAGE Encyclopedia of Social Science Research Methods. Thousand Oaks, California.

Kachelmeier, S. J. (1994). Discussion of “an experimental investigation of alternative damage-sharing liability regimes with an auditing perspective.” Journal of Accounting Research, 32(Supplement), 131–139.

Kachelmeier, S. J. (1996). Discussion of “tax advice and reporting under uncertainty: Theory and experimental evidence.” Contemporary Accounting Research, 13, 81–89.

Kaptein, M. (2011). Toward effective codes: Testing the relationship with unethical behaviour. Journal of Business Ethics, 99(2), 233–251.

Karpoff, J. M., Lee, D. S., & Martin, G. S. (2008). The cost to firms of cooking the books. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 43(3), 581–611.

Keil, M., & Robey, D. (2001). Blowing the whistle on troubled software projects. Communication of the ACM, 44(4), 87–93.

Koh, H. P., Scully, G., & Woodliff, D. R. (2011). The impact of cumulative pressure on accounting students’ propensity to commit plagiarism: An experimental approach. Accounting & Finance, 51(4), 985–1005.

Koh, H. P., Scully, G., & Woodliff, D. R. (2018). Can anticipating time pressure reduce the likelihood of unethical behaviour occurring? Journal of Business Ethics, 153(1), 197–213.

Kuang, X., & Moser, D. V. (2009). Reciprocity and the effectiveness of optimal agency contracts. The Accounting Review, 84(5), 1671–1694.

Levinson, H. (2009). Reciprocation: The relationship between man and organisation. Consulting psychology: Selected articles by Harry Levinson (pp. 31–47). American Psychological Association.

Loe, T. W., & Weeks, W. A. (2000). An experimental investigation of efforts to improve sales students’ moral reasoning. Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management, 20(4), 243–251.

Long, C. P. (2018). To control and build trust: How managers use organizational controls and trust-building activities to motivate subordinate cooperation. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 70, 69–91.

Long, J. H., & Basoglu, K. A. (2016). The impact of task interruption on tax accountants’ professional judgment. Accounting, Organisations and Society, 55, 96–113.

Luft, J. (1997). Fairness, ethics and the effect of management accounting on transaction costs. Journal of Management Accounting Research, 9, 199–216.

Maas, V. S., & Van Rinsum, M. (2013). How control system design influences performance misreporting. Journal of Accounting Research, 51(5), 1159–1186.

Maas, V. S., & Yin, H. (2022). Finding partners in crime? How transparency about managers’ behaviour affects employee collusion. Accounting, Organisations and Society, 96, 101293.

Maitland, I., Bryson, J., & Ven de Ven, A. (1985). Sociologists, economists, and opportunism. Academy of Management Review, 10(1), 59–65.

Mass, V. S., & van Rinsum, M. (2013). How control system design influences performance misreporting. Journal of Accounting Research, 51(5), 1159–1186.

Mayhew, B. W., & Murphy, P. R. (2009). The impact of ethics education on reporting behaviour. Journal of Business Ethics, 86(3), 397–416.

Mayhew, B. W., & Murphy, P. R. (2014). The impact of authority on reporting behaviour, rationalization, and affect. Contemporary Accounting Research, 31(2), 420–443.

Mazar, N., Amir, O., & Ariely, D. (2008). The dishonesty of honest people: A theory of self-concept maintenance. Journal of Marketing Research, 45(6), 633–644.

McGuire, S. T., Omer, T. C., & Sharp, N. Y. (2012). The impact of religion on financial reporting irregularities. The Accounting Review, 87(2), 645–673.

Merchant, K. A., Van der Stede, W. A., & Zheng, L. (2003). Disciplinary constraints on the advancement of knowledge: the case of organisational incentive systems. Accounting Organisations and Society, 1, 251–286.

Murphy, P. R., & Dacin, M. T. (2011). Psychological pathways to fraud: Understanding and preventing fraud in organizations. Journal of Business Ethics, 101(4), 601–618.

Murphy, P. R., & Free, C. (2016). Broadening the fraud triangle: Instrumental climate and fraud. Behavioral Research in Accounting, 28(1), 41–56.

Nelson, M. W., & Rupar, K. K. (2015). Numerical formats within risk disclosures and the moderating effect of investors’ concerns about management discretion. The Accounting Review, 90(3), 1149–1168.

Newman, A. H. (2014). An investigation of how the informal communication of firm preferences influences managerial honesty. Accounting, Organisations and Society, 39(3), 195–207.

Organ, D. W., Podsakoff, P. M., & MacKenzie, S. B. (2006). Organisational Citizenship Behaviour: Its Nature, Antecedents, and Consequences. Sage.

Orin, R. M. (2008). Ethical guidance and constraint under the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002. Journal of Accounting, Auditing & Finance, 23(1), 141–171.

Palmer, D. E., & Zakhem, A. (2001). Bridging the gap between theory and practice: Using the 1991 federal sentencing guidelines as a paradigm for ethics training. Journal of Business Ethics, 29(1), 77–84.

Palmrose, Z. V., & Scholz, S. (2004). The circumstances and legal consequences of non-GAAP reporting: Evidence from restatements. Contemporary Accounting Research, 21(1), 139–180.

Pauls, C. A., & Stemmler, G. (2003). Substance and bias in social desirability responding. Personality and Individual Differences, 35(2), 263–275.

Ploner, M., & Regner, T. (2013). Self-image and moral balancing: An experimental analysis. Journal of Economic Behaviour & Organisation, 93, 374–383.

Ponemon, L. A., & Gabhart, D. R. (1990). Auditor independence judgments: A cognitive-developmental model and experimental evidence. Contemporary Accounting Research, 7(1), 227–251.

Pruckner, G. J., & Sausgruber, R. (2013). Honesty on the streets: A field study on newspaper purchasing. Journal of the European Economic Association, 11(3), 661–679.

Richards, C. (1999). The transient effects of limited ethics training. Journal of Education for Business, 74(6), 332–334.

Rixom, J., & Mishra, H. (2014). Ethical ends: Effect of abstract mindsets in ethical decisions for the greater social good. Organisational Behaviour and Human Decision Processes, 124(2), 110–121.

Rousseau, D. M. (1989). Psychological and implied contracts in organisations. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal, 2(2), 121–139.

Rousseau, D. M. (1990). New hire perceptions of their own and their employer’s obligations: A study of psychological contracts. Journal of Organisational Behaviour, 11(5), 389–400.

Sama, L. M., & Shoaf, V. (2008). Ethical leadership for the professions: Fostering a moral community. Journal of Business Ethics, 78(1), 39–46.

Sánchez-Expósito, M. J., & Naranjo-Gil, D. (2017). Effects of management control systems and cognitive orientation on misreporting: An experiment. Management Decision., 55(3), 579–594.

Sanders, K., & Schyns, B. (2006). Leadership and solidarity behaviour: Consensus in perception of employees within teams. Personnel Review, 35(5), 538–556.

Sanders, K., Schyns, B., & Koster, F. (2006). Organisational citizens or reciprocal relationships? An empirical comparison. Personnel Review, 35(5), 519–537.

Securities and Exchange Commission. (2003a). Disclosure Required By Sections 406 and 407 of the Sarbanes Oxley Act of 2002. Release Nos. 33–8177; 34–47235; File No. S7–40–02. (January). http://www.sec.gov/rules/final/33-8177.htm. Accessed 27 May 2022.

Securities and Exchange Commission. (2003b). NASD and NYSE Rulemaking: Relating to Corporate Governance. Release No. 34–48745. (November). https://www.sec.gov/rules/sro/34-48745.htm. Accessed 27 May 2022

Shariff, A. F., & Norenzayan, A. (2007). God is watching you priming God concepts increases prosocial behaviour in an anonymous economic game. Psychological Science, 18(9), 803–809.

Shore, L. M., & Wayne, S. J. (1993). Commitment and employee behaviour: Comparison of affective commitment and continuance commitment with perceived organisational support. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78(5), 774–780.

Shu, L. L., Gino, F., & Bazerman, M. H. (2012). Ethical discrepancy: Changing our attitudes to resolve moral dissonance. In: Behavioural Business Ethics (pp. 235–254). Routledge.

Singh, J. B. (2011). Determinants of the effectiveness of corporate codes of ethics: An empirical study. Journal of Business Ethics, 101(3), 385–395.

Smith, H. J., Thompson, R., & Iacovou, C. (2009). The impact of ethical climate on project status misreporting. Journal of Business Ethics, 90(4), 577–591.

Stevens, B. (1994). An analysis of corporate ethical code studies: “Where do we go from here?” Journal of Business Ethics, 13(1), 63–69.

Tangpong, C., Li, J., & Hung, K. T. (2016). Dark side of reciprocity norm: Ethical compromise in business exchanges. Industrial Marketing Management, 55, 83–96.

Tenbrunsel, A. E., & Messick, D. M. (2004). Ethical fading: The role of self-deception in unethical behaviour. Social Justice Research, 17(2), 223–236.

Trevino, L. K. (1992). Experimental approaches to studying ethical-unethical behaviour in organisations. Business Ethics Quarterly, 1, 121–136.

Uhl-Bien, M., & Maslyn, J. M. (2003). Reciprocity in manager-subordinate relationships: Components, configurations, and outcomes. Journal of Management, 29(4), 511–532.

Valentine, S., & Fleischman, G. (2004). Ethics training and businesspersons’ perceptions of organisational ethics. Journal of Business Ethics, 52(4), 391–400.

Warren, D. E., Gaspar, J., & Laufer, W. S. (2014). Is formal ethics training merely cosmetic? : A study of ethics training and ethical organisational culture. Business Ethics Quarterly, 24(1), 85–117.

Welsh, D. T., & Ordóñez, L. D. (2014). Conscience without cognition: The effects of subconscious priming on ethical behaviour. Academy of Management Journal, 57(3), 723–742.

Zhang, Y. (2008). The effects of perceived fairness and communication on honesty and collusion in a multi-agent setting. The Accounting Review, 83(4), 1125–1146.

Zhao, H., Xia, Q., He, P., Sheard, G., & Wan, P. (2019). Workplace ostracism and knowledge hiding in service organisations: Corrigendum. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 77, 290–291.

Acknowledgements

We thank Kevin Baird, Koh Hwee Ping, Stijn Masschelein, David Smith, John Sands, and three anonymous referees for their helpful comments and suggestions on earlier drafts of this paper. Comments by participants in the research seminars at The University of Western Australia are appreciated. An earlier version of this paper was presented at the 2019 Accounting and Finance Association of Australia and New Zealand Doctoral Symposium, Brisbane, and the 2019 Asia-Pacific Management Accounting Association Annual Conference, Doha, Qatar. This paper is based in part on the first author’s Ph.D. thesis completed at The University of Western Australia. The first author acknowledges the funding support from the Indonesia Endowment Fund for Education Scholarship and the University of Western Australia Scholarship for International Research Fees.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Research involving Human Participants and/or Animals

An ethical approval (RA/4/20/4525) was granted for this research project from the Human Research Office, The University of Western Australia.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in this research project.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1 Experimental Case Materials

Case 1 (Commitment Reminder Absent – Reciprocity in the workplace Absent)

Instructions: This business case concerns Carpenter Company and a situation that is occurring at one of its subsidiaries: Glam Company. Please read the case carefully and answer the questions at the end as if this was a real situation. Please note there are no correct or incorrect answers.

Carpenter is a company in the wood industry headquartered in city A in one of the states in the USA. The Company is not listed on any stock exchange.

Glam is one of the subsidiaries which is located in city C. Glam’s main activities are producing and selling picture frames. Kim Green has been Glam’s general manager (GM) for the last five years.

Carpenter has an established Code of Ethics. The purpose of the Code of Ethics is to promote the honest and ethical conduct of all board members, senior executives, general managers, and all other employees of Carpenter, including accurate, timely, and understandable disclosure in periodic reports. All employees in Carpenter sign a statement that they will comply with the code of ethics.

Glam’s Bonus Scheme.

Each subsidiary is organized as a profit center. Carpenter has set a bonus scheme for Glam’s employees based on Glam’s profit performance. If the Glam’s realized profit beats the target level, Carpenter will give substantial bonuses to Glam’s employees. However, Kim Green, as the subsidiary’s GM, has a different bonus scheme, which is based on the growth of the market share of Glam’s products.

For the past two years, Glam’s profitability has been below its target. This poor performance by Glam has resulted in its employees not receiving any bonus payments for the past two years.

Glam’s Business Activities.

The working environment at Glam is very harmonious. Once every three months, Glam conducts a family gathering for its employees to promote fellowship among employees and their families. Everyone in Glam seems willing to help each other, not only about work but also in family matters.

In January 2019, Kim reviewed Glam’s 2018 sales and operating costs report. Kim was very pleased to learn that Glam’s profit had exceeded its target. However, previously, Kim had heard a rumor from a fellow GM in the same industry that there was a new laboratory test that could determine any flaw in a specific wood material inventory. Kim knew that the majority of Glam's material inventory consists of the specific wood and wondered whether she/he should instruct the warehouse manager to conduct the laboratory test.

Kim realizes that if the instruction for laboratory testing of the material inventory is given, and the flaw is proven, then a significant amount of the material inventory will possibly have to be written off. However, Kim finds out that the external auditor had found no concerns about Glam's material inventory and had issued an unqualified report and that the headquarters is not aware about the rumor of the new laboratory test for determining the flaw in the material inventory.

If the flaw is proven and the flaw inventories are written off, Glam’s profit will be reduced, and the 2018 profit target will not be met. This means that all employees will not receive their bonus payments for this year.

However, as Glam’s GM, Kim will still receive a bonus since the GM’s bonus is based on the growth of market share of Glam’s products, which has been achieved.

Your Decision:

Based on the circumstances in the business case described above, we would like to know what action you think Kim Green will take regarding the new laboratory test that might determine flaws in the specific wood material inventory.

-

1.

What action do you think Kim Green will take? (Circle one of the numbers)

Do nothing | Instruct to take the laboratory test | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

-

2.

Imagine that you are in the same situation as Kim Green. What action would you take? (Circle one of the numbers)

Do nothing | Instruct to take the laboratory test | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

-

3.

Kim Green had a chat with Glam’s warehouse manager about her/his plan to enroll her/his child to a prestigious school in the city

-

a.

Yes

-

b.

No

-

a.

-

4.