Abstract

In this paper, we describe the genesis of Boscovich’s Sectionum Conicarum Elementa and discuss the motivations which led him to write this work. Moreover, by analysing the structure of this treatise in some depth, we show how he developed the completely new idea of “eccentric circle” and derived the whole theory of conic sections by starting from it. We also comment on the reception of this treatise in Italy, and abroad, especially in England, where—since the late eighteenth century—several authors found inspiration in Boscovich’s work to write their treatises on conic sections.

Sunto

In questo lavoro delineamo la genesi del Sectionum Conicarum Elementa di Boscovich, e discutiamo le motivazioni che indussero Boscovich a scrivere quest’opera. Inoltre, analizzando in dettaglio la struttura di questo trattato, mostriamo come egli sviluppò l’idea completamente nuova di “cerchio eccentrico”, e costruì partendo da questa nozione l’intera teoria delle sezioni coniche. Commentiamo anche sulla ricezione del suo trattato, sia in Italia che all’estero, specialmente in Inghilterra, dove—a partire dalla fine del diciottesimo secolo—vari autori si ispirarono all’opera di Boscovich per scrivere i loro trattati sulle sezioni coniche.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

“… in ipso nimirum Geometriae vestibulo usi olim sumus” (Boscovich 1754b, vii).

See (Pepe 2010) for a more detailed description of the content.

Boscovich was outside Rome between October and December 1750, in the second half of 1751 he was travelling through Lazio, Umbria and Romagna. The two surveyors covered a cumulative distance of 2000 km, up peaks as high as 1700 m, carrying hundreds of pounds of equipment on horseback, in a really epic endeavour (Boscovich and Maire 1755; Pedley 1993).

In private, Boscovich used to call his brother “Natale”.

Poco prima che io tornassi si era cominciata a stampare un’opera mia per uso della gioventù studiosa; [?] il principio della quale fatto da me in latino, era stato voltato in italiano dal P. Lazzari anni sono, e perduto il mio originale era stato di nuovo ritradotto in latino da un altro. Sarà quest’opera un corso di matematica, e questo è il primo tomo, in cui vi è la Geometria piana, e solida, l’Aritmetica, colle proporzioni, Logaritmi ecc. la Trigonometria piana, e sferica e l’Algebra, senonche forsi l’Algebra la farà (sic) separare, e invece di uno far due tometti. Le due Trigonometrie le ho rifatte da che stò qui, e l’Algebra la feci tutta a Rimini sul fine, ma la ritoccherò. See (Boscovich 2012, 203).

See the letter addressed to Natale, dated Rome 21 November 1752, Ibidem, 217.

Ivi.

See the letter to Natale dated Rome, 26 December 1752, in (Boscovich 2012, 219).

For Newton attitude towards the Cartesian method see (Guicciardini 2011, Chapter 5).

See the letter to Natale dated Rome, [January] 22nd 1754, in (Boscovich 2012, 242).

“Geometria, quae nihil usquam operatur per saltum” (Boscovich 1754, III, xviii).

See his Mathematical Collections, lib. VII, prop. 238 in (Pappus 1588, 303 versus).

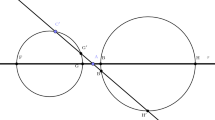

Following Taylor, we use this terminology, but other authors call it “generating circle” or even “auxiliary circle”.

Le Seur and Jacquier used the third edition of the Principia (Newton 1726).

See the Monitum opening the first volume.

These pages were written with the cooperation of the Swiss mathematician Jean Luis Calandrini (1702–1758), who also financed the publication, and took part in drawing up the footnotes which are marked with “✳”.

In modern terms, this means that the “intersection divisor” at P is 3P.

See (Huygens 1673).

See (Leibniz 1686). Nevertheless, Leibniz erroneously believed that the “osculation” consisted in the coincidence of two contacts; that is, the intersection divisor was 4P. This is not true in general, as it can be easily seen in a general point of a conic, but it is true at the both vertices of the transverse axis of the ellipse and of the hyperbola, and the vertex of the parabola.

See for instance (Brackenridge and Nauenberg 2002).

See (Newton 1739–42, I, 140, note (e); 141 note 230).

See (Newton 1739–42, I, 144, note 239).

(Newton 1739–42, I, 122, 127).

See (Apollonius 1566, I, prop. 20, 21, 49, 50), (Apollonius 1896, proposition 22 (I, 49)), also (Newton 1967–81, VI, 145 (119)). The latus rectum, or parameter, pertaining to any diameter of a conic section is explicitly defined in [La Hire 1685, 45–46]. We stress that Newton had read La Hire’s Sectiones Conicae, and in fact he referred to it in the last scholium in Sect. 4 of book I of the Principia, see later on. We also notice that the same definitions appear in the account on conic sections inserted in (Guarini 1671, 394–395).

This result is implicitly claimed in Newton’s proposition X.

See (L’Hospital 1707).

Newton was referring to (La Hire 1685).

See for instance (Del Centina and Fiocca 2018).

The Accademia was founded in 1690 with the aim to cultivate the sciences and to awaken good literary taste. In 20 years from its foundation, the Academy counted almost one thousand three hundred members, among whom there were cardinals, princes and prelates, but also dames (Crescimbeni 1711).

“To cultivate Geometry, and promote Astronomy”.

See (Newton 1739–42, lemma XVII, sect. V), and footnote (y). This means that the ratio does not change if the chords are moved parallel to themselves.

See (Apollonius Apollonius of Perga 1959, 210–223).

Newton knew the theorem since the end of the 1670s, (Newton1967–81, IV, 358–359).

Milne (1927, 96) remarked that when the law has been established that the orbit of a planet is a conic section described under the action of a force situated at the focus, two kinds of problems arise: to describe an orbit having given the focus and three other conditions, and to describe an orbit satisfying five conditions, when the focus is not given. The two problems are solved by Newton, respectively, in sections IV and V.

This is substantially the proof found in Newton’s manuscripts, see (Newton 1967–81, IV, 358–359).

De L’Hospital defined the parabola by directrix, focus and determining ratio, while ellipse and the hyperbola, respectively, as the locus of points such that the sum, or the difference, of the squares of their distances from the foci is constant.

Michelamgelo Giacomelli (1695–1774) was an erudite priest who was very influential in Rome around the middle of the eighteenth century. He maintained a scientific correspondence with Guido Grandi, and, in 1745, he became co-editor (with Gaetano Cenni) of the Giornale de’ Letterati founded in 1742.

In the first case the proof immediately follows from Euclid’s Elements prop. 5 book 2, and in the second from prop. 6 same book. In the following, we will use the formula \( DF \times FE = PE^{2} - PF^{2} \), by supposing PE > PF, otherwise the sign has to be changed.

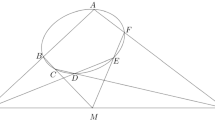

Boscovich wants to say: If the chord BC moves parallel to itself and becomes tangent to the conic at a certain point X, then CPB: bPC = P'X2: bP'c, being P' the point of intersection of the tangent with the chord bc. Boscovich applies the geometrical continuity in the form of “the principle of permanence of functional relations”, see (Del Centina and Fiocca 2018). Boscovich will use this remark in the Proof of Theorem 4.

The diameter perpendicular to the directrix is called transverse axis, and the diameter parallel to the directrix is called conjugated axis.

In the case of the parabola, the straight line perpendicular to the directrix through the focus is called transverse axis.

We notice that the argument used here is questionable, and, in fact, in Sectionum Conicarum Elementa Boscovich proved this result in another way, see cor. 6 to prop. V in (Boscovich 1754a, No. 221).

(Boscovich 1754a, vii).

See (Newton 1739–1742, vol. 3, 247–282).

This is today commonly called eccentricity and denoted e, a symbol which for simplicity we also adopt in the sequel.

For details, see (Del Centina and Fiocca 2018).

Boscovich postponed the definition of latus rectum pertaining to any diameter after proposition VII.

A circumstance already remarked by Briggs, see (Del Centina and Fiocca 2018).

See (Del Centina and Fiocca 2018) for more information.

“Mirum sane quam foecunda est haec constructio, quam Tyroni exercendo apta”, [Boscovich 1754a, No. 145].

“altera intersectione ita in infinitum abeunte, ut nusquam jam sit”, (Boscovich 1754a, No. 154).

Boscovich, without saying it, is supposing L to be the point of intersection of the two chords mentioned in the statement.

Given three magnitudes a < b < c, b is said the harmonic mean between a and c if the proportion a:c = (b − a):(c − b) holds true. Boscovich considered QT = a, QK = b, Qt = c. In the case of the hyperbola, when T and t are not on the same branch (Fig. 22b), Boscovich considered Kt = a, QK = b, KT = c.

See (La Hire 1685, books I, II).

The first volume of the Elementa was translated almost entirely in Italian by Luigi Panizzoni and published in 1774. See (Pepe 2010, 16).

More information concerning the mathematical treatises of the second half of the eighteenth century in Italian in (Pepe 2010, 23–24).

In addition to the Compendio, Grandi published the Le Istituzioni delle sezioni coniche, first written in Latin (Naples 1737), then translated into Italian (Florence 1744, Venice 1746).

See for instance (Del Centina and Fiocca 2018), and the references therein.

“ce Traité fait le troisième Volume de ses Elémens de Mathématiques; le génie de l’Auteur y brille autant que dans ses Ouvrages les plus sublimés; sa manière de considérer les Sections coniques en général & en particulier, de démontrer leurs rayons osculateurs, & leurs autres propriétés les plus difficiles, fait voir un Géomètre profond qui justifie dans les moindres choses la réputation qu’il a depuis long-temps d’un des plus grands Mathématiciens de notre-siècle, & forme le Traité le plus curieux que nous ayons vû sur les Sections Coniques”, Journal des Sçavans, Avril 1766, p. 240.

Five contributions concerning this subject are included in Boscovich (1993).

Erroneously Leslie indicated the 1744 as the year of publication of Boscovich’s treatise on conic sections.

We notice that this Association was founded in 1876 by a number of mathematicians who, “from experience as teachers reached the conviction that Euclid was not a suitable introduction to geometry for the ordinary immature minds”.

The journal devoted to elementary mathematics of the Association for the Improvement of Geometrical teaching. Langley is also known for having inspired Eric. T. Bell to continue to study mathematics.

References

Apollonius of Perga. 1566. Conicorum Libri Quatuor. Cum commentariis Federici Commandini. Bononie: A. Benatii.

Apollonius of Perga. 1896. In Treatise on Conic Sections, ed. T.L. Heath. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Apollonius of Perga. 1959. Les Coniques, œuvres traduites pour la première fois du Grec en Français par P. Ver Eecke. Paris: Albert Blanchard.

Boscovich, R.J. 1740. De circulis osculatoris dissertatio. Romae: ex typographia Komarek.

Boscovich, R.J. 1741. De inaequalitate gravitatis in diversis Terrae locis. Romae: ex typographia Komarek.

Boscovich, R.J. 1743. De motu corporis attracti in centrum immobile viribus decrescentibus in ratione distantiarum reciproca duplicata in spatiis non resistentibus. Romae: ex typographia Komarek.

Boscovich, R.J. 1744. Nova methodus adhibendi phasium observationes in eclipsibus lunaribus ad exercendam Geometriam, & promovendam Astronomiam. Romae: ex typographia Komarek.

Boscovich, R.J. 1746. Dimostrazione facile d’una principale proprietà delle Sezioni Coniche, la quale non dipende da altri teoremi Conici; e disegno d’un nuovo metodo di trattare quella dottrina. Giornale de’ Letterati Art. XIX giugno e luglio 1746: 189–193, 241–243, 315–316.

Boscovich, R.J. 1747. De maris aestu. Romae: ex typographia Komarek.

Boscovich, R.J. 1752. Elementa Universae Matheseos, 2 vols. Romae: Salomoni.

Boscovich, R.J. 1754. Elementa Universae Matheseos, 3 vols. Romae: Salomoni.

Boscovich, R.J. 1754a. Sectionum Conicarum Elementa, nova quadam methodo concinnata. In (Boscovich 1754, III, 1–296).

Boscovich, R.J. 1754b. Dissertatio de transformatione locorum geometricorum. In (Boscovich 1754, III, 297–468).

Boscovich, R.J. 1757. Elementa Universae Matheseos, 3 vols. Venetiis: Perlini.

Boscovich, R.J. 1758. Philosophiae naturalis theoria redacta ad unicam legem virium in natura existentium. Viennae: Officina libraria Kaliwodiana.

Boscovich, R.J. 1993. In Vita e attività scientifica/His Life and Scientific Work, ed. Piers Bursill-Hall. Roma: Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana.

Boscovich, R.J. 2012. Carteggio con Natale Boscovich (1730–1758). In Edizione Nazionale delle Opere e della Corrispondenza di Ruggiero Giuseppe Boscovich. Corrispondenza, Vol. III, tomo I, a cura di Edoardo Proverbio. http://www.edizionenazionaleboscovich.it/.

Boscovich, R.J., T. Le Seur, and F. Jacquier. 1742. Parere di tre matematici sopra i danni che si sono trovati nella cupola di S. Pietro sul fine dell’anno MDCCXLII. Roma.

Boscovich, R.J., T. Le Seur, and F. Jacquier. 1743. Riflessioni sopra alcune difficoltà spettanti i danni e risarcimenti della cupola di S. Pietro. Roma.

Boscovich, R.J., and C. Maire. 1755. De litteraria expeditione per pontificiam ditionem ad dimetiendos meridiani gradus et corrigendam mappam geographicam. Roma: N. and M. Palearini.

Brackenridge, J.B., and M. Nauenberg. 2002. Curvature in Newton’s dynamics. In The Cambridge companion of Newton, ed. I.B. Cohen and G.E. Smith, 85–137. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bussotti, P., and R. Pisano. 2014. On the Jesuit Edition of Newton’s Principia. Science and Advanced Researches in the Western Civilization. Advances in Historical Studies 3(1): 33–55.

Casey, J. 1885. A treatise on the analytical geometry of the point, line, circle, and conic sections, containing an account of its most recent extensions, with numerous examples. Dublin: Hodges, Figgis and Co.

Casini, P. 1983. Newton e la coscienza europea. Bologna: Il Mulino.

Chasles, M. 1837. Aperçu historique sur l’origine et le développement des méthodes en géométrie. Paris: Gauthier-Villars.

Crescimbeni, G.M. 1711. Storia dell’Accademia degli Arcadi istituita in Roma l’anno 1690. Roma: Antonio De Rossi.

Del Centina, A. 2016. On Kepler’s system of conics in Astronomiae par Optica. Archive for History of Exact Sciences 70: 567–589.

Del Centina, A., and A. Fiocca. 2018. Boscovich’s geometrical principle of continuity and the “mysteries of the infinity”. Historia Mathematica 45(2): 131–175.

Feingold, M. 1993. A Jesuit among the Protestants: Boscovich in England c. 1745–1820. In (Boscovich, 1993, 511–526).

Field, J.V. 1986. Two mathematical inventions in Kepler’s Ad Vitellinem Paralipomena. History and Philosophy of Science, Part A 17: 449–468.

Guarini, G. 1671. Euclides adauctus et methodicus mathematicaque universalis. Augustae Taurinorum: B. Zapatae.

Guicciardini, N. 1999. Reading the Principia, the Debate on Newton’s mathematical methods for natural philosophy from 1687 to 1736. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press.

Guicciardini, N. 2011. Isaac Newton on Mathematical Certainty and Method. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Guicciardini, N. 2015. Editing Newton in Geneva and Rome: The Annotated Edition of the Principia by Calandrini, Le Seur and Jacquier. Annals of Science 72(3): 37–380.

Haslam, S.H., and J. Edwards. 1881. Conic sections treated geometrically. London: Longmans Green and Co.

Huygens, C. 1673. Horologium oscillatorium sive de motu pendulorum ad horologia aptatu demonstrationes geometricae. Pariis: Apud F. Muguet.

de L’Hospital, G.F.A. 1707. Traité analytique des sections coniques et de leur usage pour la résolution des équations dans les problèmes tant détermines qu’indéterminés. Paris: Chez la veuve de Jean Boudot et Jean Boudot fils.

La Hire, Ph. 1685. Sectiones Conicae, in novem libros distributae. Paris: S. Miclallet.

Lalande, and J.-J. de Lefrançois. 1764. Astronomie. Tome second. Paris: Chez Desaint & Saillant.

Langley, E.M. 1894. The Eccentric Circle of Boscovich. The Mathematical Gazette 1(1–3): 17–19.

Leibniz, G.W. 1686. Meditatio nova de natura anguli contactus et osculi. Acta Eruditorum Anno MDCLXXXVI: 289–292.

Le Poivre, J.-F. 1704. Traité des sections du cylindre et du cône considérées dans le solide et dans le plan. Paris: Barthelemy Girin.

Le Poivre, J.-F. 1708. Traité des sections du cône considérées dans le solide, avec des démonstrations simples et nouvelles, plus simples et plus générales que celles de l’édition de Paris. Mons: G. Migeot.

Leslie, J. 1821. Geometrical Analysis, and Geometry of Curve Lines, Being Volume Second of A Course of Mathematics, and Designed as an Introduction to the Study of Natural Philosophy. Edinburgh: W. & C. Tait.

Metzburg, G.I. 1780–1791. Institutiones mathematicae in usum tironum conscriptae. Editio tertia, 7 vols. Viennae: Typis Johan. Thomae nob. De Trattnern.

Metzburg, G.I. 1783. Elementa sectionum conicarum. In (Metzburg 1780–1791, vol. II, 151–200).

Milne, J.J. 1927. Newton’s Contribution to the Geometry of Conics. In Isaac Newton 1642–1727: A memorial volume edited for the Mathematical Association, ed. W.J. Greenstreet, 96–114. London: Bell & Sons.

Newton, I. 1687. Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica. Londini: Typis Josephi Streater.

Newton, I. 1707. Arithmetica Universalis. Cantabrigiae: Typis Academicis.

Newton, I. 1726. Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica, editio tertia aucta & emendata. London: Apud Guil. & Joh. Innys.

Newton, I. 1739–42. Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica, perpetuis commentariis illustrata, communi studio PP. Thomae Le Seur & Francisci Jacquier ex Gallicana Minimorum Familia, Matheseos Professorum, 3 vols. Geneve: Typis Barillot.

Newton, I. 1967–81. The Mathematical Papers of Isaac Newton. In ed. D.T. Whiteside, 8 vols. Cambridge: Cambridge University press.

Newton, T. 1794. A Short Treatise on the Conic Sections in which the three curves are derived from a general description on the plane and the most useful properties of each are deduced from a common principle. Cambridge: John Archdeacon and John Burges.

Pappus d’Alexandrie. 1588. Mathematicae Collectiones a Federico Commandino Urbinate in latinum conversae et commentaris illustratae. Venetiis: Apud Franciscus de Franciscis Senensem.

Pedley, M. 1993. “I Due Valentuomini Indefessi”: Christopher Maire and Roger Boscovich and the Mapping of the Papal States (1750–1755). Imago Mundi 45: 59–76.

Pepe, L. 2010. Introduzione. In Edizione nazionale delle opere e della corrispondenza di Ruggiero Giuseppe Boscovich, Opere a stampa, volume II, 11–28. http://www.edizionenazionaleboscovich.it/.

Pepe, L. 2016. Insegnare matematica. Storia degli insegnamenti matematici in Italia. Clueb: Bologna.

Poncelet, J.-V. 1822. Traité des propriétés projectives des figures. Paris: Bachelier.

Rigutti, M. 2010. Introduzione. In Edizione nazionale delle opere e della corrispondenza di Ruggiero Giuseppe Boscovich, Opere a stampa volume V/V, 11–37. http://www.edizionenazionaleboscovich.it/.

Saint-Vincent, G. 1647. Opus geometricum quadraturae circuli et sectionum coni decem libris comprehensum. Antverpiae: Apud Ioannem et Iacobum Meursios.

Smith, C. 1894. Geometrical Conics. London: Macmillan and Co.

Stirling, J. 1717. Lineæ Tertii Ordinis Neutonianæ, Sive Illustratio Tractatus D. Neutoni de Enumeratione Linearum Tertii Ordinis, Cui Subjungitur, Solutio Trium Problematum. Oxoniæ: Ex Theatro Sheldoniano.

Tacquet, A. 1745. Elementa Euclidea Geometriae Planae, ac Solidae; et Selecta ex Archimede Theoremata: eiusdemque Trigonometria Plana, Plurimis Corollariis, Notis, ac Schematibus quadraginta illustrata a Gulielmo Whiston; quibus nunc primum accedunt Trigonometria Sphærica Rogerii Josephi Boscovich S.J. & Sectiones Conicæ Guidonis Grandi, Annotationibus satis amplis Octaviani Cameti explicatæ, 2 vols. Romæ: Hieronymi Mainardi.

Taylor, C. 1881. An Introduction to the Ancient and Modern Geometry of Conics. Cambridge: Deighton Bell and co.

Taylor, C. 1884. The Discovery and the Geometrical Treatment of the Conic Sections. In Tenth General Report of the Association for the Improvement of Geometrical Teaching, 43–55. Birmingham: Herald Press.

Walker, G. 1794. A Treatise on the Conic Sections. London: Charles Dilly.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by Niccolò Guicciardini.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Del Centina, A., Fiocca, A. “A masterly though neglected work”, Boscovich’s treatise on conic sections. Arch. Hist. Exact Sci. 72, 453–495 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00407-018-0213-3

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00407-018-0213-3