- Ca' Foscari University of Venice, Venice, Italy

If I close my eyes, the absence of light activates the peripheral cells devoted to the perception of darkness. The awareness of “seeing oneself seeing” is in its essence a thought, one that is internal to the vision and previous to any object of sight. To this amphibious faculty, the “diaphanous color of darkness,” Aristotle assigns the principle of knowledge. “Vision is a whole perceptual system, not a channel of sense.” Functions of vision are interwoven with the texture of human interaction within a terrestrial environment that is in turn contained into the cosmic order. A transitive host within the resonance of an inner-outer environment, the human being is the contact-term between two orders of scale, both bigger and smaller than the individual unity. In the perceptual integrative system of human vision, the convergence-divergence of the corporeal presence and the diffraction of its own appearance is the margin. The sensation of being no longer coincides with the breath of life, it does not seems “real” without the trace of some visible evidence and its simultaneous “sharing”. Without a shadow, without an imprint, the numeric copia of the physical presence inhabits the transient memory of our electronic prostheses. A rudimentary “visuality” replaces tangible experience dissipating its meaning and the awareness of being alive. Transversal to the civilizations of the ancient world, through different orders of function and status, the anthropomorphic “figuration” of archaic sculpture addressees the margin between Being and Non-Being. Statuary human archetypes are not meant to be visible, but to exist as vehicles of transcendence to outlive the definition of human space-time. The awareness of individual finiteness seals the compulsion to “give body” to an invisible apparition shaping the figuration of an ontogenetic expression of human consciousness. Subject and object, the term “humanum” fathoms the relationship between matter and its living dimension, “this de facto vision and the ‘there is’ which it contains.” The project reconsiders the dialectic between the terms vision–presence in the contemporary perception of archaic human statuary according to the transcendent meaning of its immaterial legacy.

Introduction

As if absence was a volume inhabiting the space around us, returning home and, say, noting the arrangement of objects, identical, albeit now bathed in a different shade of light, who hasn't faced one day a place suddenly unrecognizable? For reality is a before-ness and an inside-ness—“thought through my eyes” (Joyce, 2012)—that resides within the observer's vision.

If I close my eyes, the absence of light activates the peripheral cells devoted to the perception of darkness (von Helmholtz, 1962; Gregory, 1990). The awareness of “seeing oneself seeing” is in its essence a thought, one that is internal to the vision and preceding any object of sight. To this amphibious faculty, the “diaphanous color of darkness,” Aristotle (1907) assigns the principle of knowledge (Aristotle, 1907; Agamben, 2005). In Muḥiddīn Ibn ‘Arabī’ (1981) neat metaphor, the outer rind and inner stone of a fruit (El-Qishr; wa'l-Lobb) or, in other words the dynamic binding each point of the circumference to its permanent principle of irradiation, the center (Guénon, 1995).

“Vision is a whole perceptual system, not a channel of sense” (Gibson, 1986a).

The head-eye structure conducts thoughts and acts from the summit of a body whose erect posture is orthogonal to the surface of the Earth onto where it stands. Functions of vision are interwoven with the texture of human interaction within a terrestrial environment (Gibson, 1986b) that is in turn contained into the cosmic order.

The sensation of being, the here and now, no longer coincides with the breath of life, it does not seems “real” without the trace of some visible evidence and its simultaneous “sharing.” Without a shadow, without an imprint, and destined for multiple invisible witnesses, the numeric copia of the physical presence inhabits the transient memory of our electronic prostheses. As information anticipates and alters the flow of events, the indefinite plethora of news erase them one after another; in the same way, a rudimentary “visuality” (Crary, 2013) replaces tangible experience dissipating its meaning and the awareness of being alive.

Ontological Structure

In ancient times, the symbolon of Mysteries is the accidental fracture of a primordial whole: a stone or a stick broken and then re-joined, wherein the re-conjunction of the divided elements authenticates their relationship.

As we know, the universal character of Being, in its neutral plural form, ta ónta (from ἔιναι, to be), does not express multiple realities, but rather the wholeness, like Heidegger's Seiende, of that which is. As “principle of the manifestation” (Guénon, 2001), the unity of Being is suspended in the dual margin, between the undivided flow of internal sense and that of its ever-changing manifest refraction.

In the perceptual integrative system of human vision, the convergence-divergence of the corporeal presence and the diffraction of its own appearance is the margin.

The inside of an outside that is the outside of the inside (Merleau-Ponty, 1964; Johnson, 1993) joins and splits in a chi-shaped (χ) anatomical formation named chiasm (from chiázō, χιáζω, to cross, to go through) set in the cranial cavity, where the optic nerves cross and join the visual impulses.

For Plato (2007) the “Soul of the world,” that regulates the motion of the universe intersects two circles in the figure of a chi (χ) traced by the Demiurge, wherein the obliquity of the Ecliptic represents the axis of the Other with respect to the Equator, which is the axis of the Self. By definition without a subject, the reflexive relation encompasses necessarily the presence of another term, it-self.

The particle se, (Gr. he, Lat. sē, Skr. sva) refers to something that is habitual and, at the same time, separate. The term, itself-heauton contains both the relation of an endless parting and that of a return (Agamben, 2005)—ēthos anthrōpō daimōn—(Heraclitus: Diels and Kranz, 1903). According to the doctrine of Ittyḥād (unification), “my very separation is my union” (Ibn ‘Arabī, 2006).

Within the optic array of the Earth, the “relation of location is not given by degrees of azimuth and elevation (for example) but by the relation of inclusion” (Gibson, 1986c). Each second of an hour, each year in a century over the millennia, each grain of sand of each beach of a country of a continent are all embedded one into another according to their proportions of size or duration. A transitive host within the internal resonance of an inner-outer environment, the human being is the contact-term between two orders of scale—molecular and cosmic—both bigger and smaller than the individual unity (Simondon, 2005). “My” infra and ultra-corporeal experience of the world embodies its “Double” (Vitiello, 2001).

Tat tvam asi, “this you are” (Chāndogya Upanishad, 1921), or, as according to the inscription once carved in the pronao of the Temple of Apollo at Delphi, gnōthi seautón, “know thyself”. Gnōthi seautón.

The self-reflective shift inhabits the world since the beginning knowledge. The dual relationship between the eye and the brain, between the Eye, Hades ("Aιδης) and its Pupil, Kore–Hestía (Kóρη—‘Iστíη or ‘Eστíα), between the two birds of the Vedas on the same branch of the tree: “One of them eats the sweet berry of the pippal; the other, without eating, watches” (Calasso, 2014a). The rooting of such recognition, according to Simone Weil, is where the past transmits itself alive to future generations (Weil, 2014); looking backwards, it is the vector decoding the memory of meanings.

While for the Western culture the significance of vision is interwoven with that of knowledge, the archaic and Oriental principle associates the nexus of retinal perception and the counter impulse from the visual cortex to the cosmic respiration.

According to Homer, the human being sees through the mind or the lungs and perceives the visual imagination through breath, thumos (θυμóς, ὄσσoντo θυμ; Onians, 1951a). An aerial substance, the thumos is for the Ancients inhabited by its liquid principle condensing—like dew—the heat of the blood. An attribute of the consciousness residing in the breast of the living being, the thumos abandons the white bones of the expiring creature. psychē is the soul-breath, the vehicle carrying the principle of Life itself. Homer identifies psychē with shadows, skiά (Butler, 1900); as Pindar refers (Pindar, 1997), when Death overtakes the human being, in the Reign of Hades the “aiōnos eídōlon”—that is the soul, the shadow of Life—survives (Onians, 1951b).

The pupil is not only the messanger conveying visual data from/to the fovea and the primary cortex, it is the contact between visible and invisible worlds.

Kore, the Pupil, symbol of fertility and life, embodies the simulacrum of the Earth's vital principle—Hestía (Porphyry, 1993). First daughter of Cronus (Kρóνoς) and Rea (Ṕεα)—in the ‘physics’ of Stoics—Hestía is the immutable heart of the Earth, the center for Plato and permanent essence of things (Plato, 1892a), that is in turn the foundation of Cosmos (Plato, 1892b; Macrobius, 2011).

The Upanishads' vital breath (prāna) envisages all single perceptions as a unified whole. “Brahman is breath, Brahman is happiness (ka), Brahman is space (kha) […].” “Brahman is kha, space; space is primordial, space is windswept,” “That which is called brahman is this space, ākāsa, which is outside man. This space which is outside man is the same as the one within man…”(Calasso, 2014a). The ātman, that is the human soul, has the Universe as a body (Weil, 1956). In China, ideograms are vehicles of apparition where the spiritual expression and the true meaning of reality gives “form” to the “circulation” of the universal breath (Lagerwey, 2003).

Inner Vision and Presence

The term mystērion—related to the meaning “to initiate” (μυεν) and to that of “closing the eyes” or “the lips” (ιν)—refers to that which cannot be expressed. Celebrations of Mysteria began in Eleusi when the veiled mystes () closed the eyes to enter in the darkness plunging into his/her own unutterable intimacy. Romans named such “closure” and “entrance” into shadows in-itia. Mysteria were about trespassing the limit from where origins of the esoteric experience and metaphysical knowledge unveiled their unspeakable brightness. The apparent paradox of public celebration of Mysteria underpinned the inexpressibility of living phenomena as events belonging both uniquely to the subjective experience of the single and to the universal one (Kerényi, 1979).

There are two types of substitution: by equality or by identity. It is the difference between the shadow and the mirrored image: if the latter is the same in every mirror, the subject does not necessarily recognize his/her own identity in the respective reflection. Conversely, like the footprint in the sand, the shadow before or after each one of my steps is always and only mine (Heidegger, 2002). As the dislodged shard of rock represents the mountain or, as according to Mauritius Cornelius Escher, one single fish's scale encompasses the specie (Fishes and scales lithograph, 1959; Hofstadter, 1980), the qualitative character of identity embodies an absolute Otherness.

In a comparison of image and figure, from the root ajem-, to imitate, the imago of ancient Rome does not express an order of the idea but rather the substantial transcription (according to Pliny the Elder) of the maxima similitude “expressed” in wax, expressi cera uultus. It is the matrix of the transmutation of matter literally “taking shape” in the contact with the face itself of the dead subject, subsequently transferred to its opposite convex double in plaster (Didi-Huberman, 2000).

From the Greek skhêma (σχημα, shape, form) and from the Latin fingere, for molding, the “figure” denominates the aspect of an abstract model, it is the interior representation of what is not defined by reality: the acknowledgement of an apparition that figures—regardless—the actual presence.

For as we know, “matter is in itself not a reality but only a possibility, a ‘potentia’; it exists only by means of form” (Heisenberg, 1958).

In optical terms an image is the refraction of an object produced by a reflecting device. An array considered as a structure or an arrangement of invariants of structure for Gibson (1986d); a neural configuration or map for Damasio (2010) defined by the interrelation between its parts, the mental image is a self-reflective configuration, expanding or contracting the initial ordainment according to a universal form of which model is internal within you (Philo, 1854; Saint Thomas Aquinas, 1947–8).

In the composite articulation of the hiatus between the action of the motion system and the sensory awareness, “the voluntary act begins—according to Libet—before the conscious will to act” (2004). Gilbert Simondon, in his general hypothesis of the genesis of images (2014), relates the evolutionary process internal to the vision to three phases, which are characterized by a self-kinetic enactment that is oriented in accordance with different degrees of awareness. In the first phase of intuition and anticipation occurs an endogenous impulsion, which is impressed in a molding that harks back to the phylogeny of Being. In ancient times, the numinous character determined the appearance invading the subject's imagination with a relative independence from its conscious and unified activity.

Lucretius (2008) suggests there are simulacra penetrating the liminal parts of the soul—per rara cientque tenvem animi naturam—and entirely invading the human subject.

As an impulse trigger, desire elicits a bundle of pre-optive motor tendencies that convey the inner-vision toward pre-visualization and the construction of frames of actions that are at the limit of consciousness. In this gestation converges the entire duration of the human being's internal activity and that of the environment in which its existence unfolds. Thus, the actual sensorial perception is ruled by the dialectics of contact with the innate structures of the ancestral memory. What follows is a mental systematization of the imagined reality where the subject, appropriates an “analogon” of the world (Simondon, 2014). Such anologon is for Freeman and Vitiello a “coherent, highly textured brain activity pattern,” the “Double.” The “Double is the Mind” in its capillary entanglement with brain-matter. “Brains” are open dynamical systems where the Double, within the many-body dissipative model projects continuous time-reversal pre-figurations and “imagines” the world it produces as “hypotheses and predictions that we experience as perception” (Freeman and Vitiello, 2006, 2010, 2015).

The memory does not follow, rather it foresees and guides the—in-tention—thread of sensorial perception within an inner-outer interwoven environment (Figure 1). “Visual perception is not a passive recording of stimulus material but an active concern of the mind” (Arnheim, 1969a). Evolutive, cognitive activity unfolds within itself in the articulate pattern of a transparent architecture connecting the self-referential innate structures of the subject's to his/her immediate phenomenal relation to the world (Changeux, 2004).

Intention and Meaning

Transversal to the civilizations of the ancient world, through different orders of function, proximity and status, the anthropomorphic “figuration” (Vernant, 1990, 2003) of archaic sculpture questions the “idea of Being” plunged into the different cultural and ritual environment where human ideotypes begin to appear.

Ancient statues do not come to light in order to be visible as artworks, but rather to exist (Benjamin, 1936) as vehicles of transcendence. Archaeological heritage is the expression of a metaphysical condition that projects itself beyond manifest definition to outlive the individual space-time (Vernant, 1996a).

The “body” of Gods, intangible and present as an ever-changing immanence, is the absolute transcendence in the wholeness of unity.

The human body, this first and last object of any human knowledge, inhabits the temporal measure of its corporeal definition (Heidegger, 2005). Abode of a flow of impulses and breaths, this body is destined to dissipate again in the indeterminable-ness of reality, yet, at the threshold of its temporal measure, only its own utter one-ness inhabits it (Vernant, 1996b). In its motionless wholeness, the archaic human statue embodies the mobile complexity of living phenomena within the endless transfiguration of the space that it occupies (Figure 1). As the invisible archetype of “something that is not,” the archaic ideo-type of the human figure is certainly not that of our contemporary perception, not an “idol” exclusively seen in the static actuality of its visible evidence, bereaved of the transcendent spectrum of its function and meaning (Porphyry, 1993).

Shadow of its own frame the Greek eídōlon is a margin between Being and Non-Being, wherein “the body is an image of the soul, which is called its form” (Coomaraswamy, 1997). The statuary archetype of the human soul, that is the shadow—the Greek eídōlon, Ka for the Egyptians (Maspero, 1893; Stoichita, 1997)—embodies the wholeness of an internal figure in the transfiguration of its aspect, unique and different, within the living reflection of each viewer's vision. The awareness of individual finiteness seals the compulsion to “give body” to an invisible apparition shaping the archaic statuary figuration as an ontogenetic expression of human consciousness.

Intrinsic to the essential quality of life-pulse (Bergson, 1914) consciousness embodies and altogether transcends its own corporeal definition. Mobile and arbitrary, the phenomenal localization of consciousness belongs to the unconditioned character of volition; removed from sensation or perception, its activity proceeds according to Jaynes (1995) by “diachronic” processes of interpolation. Within the curve of the process informing the contact between intention and finality, in Sanskrit one word defines both terms “meaning” and “utility”: ârtha (Coomaraswamy, 1986). The term télos in the sense of “conclusion,” encompasses the multiplicity of its sematic determinations within one whole continuous move (Onians, 1951c). Such as the invisible crowning of destiny, volition (voulisis; Plato, 1892c) circumscribes the essence of purpose as oriented to the finality of its unfathomable meaning.

In accord with the hylomorphic principle of Aristotle's (1933) sýnolon, whereby substance is the indwelling form of which matter is composed, the “individuation” resides for Simondon in an incessant process of actualization of matter into a form. If the physical existence ends at its limits, the living being is always contemporaneous to itself.

We know the substantia, from sub stare, is “that which stands beneath,” the substratum (support) of universal manifestation and we know matter, ūly (ὔλη) is the hidden vegetative principle, the root from where the Being draws the lymph of any manifest animation (Guénon, 2002).

The individuation—that is Life—takes place in a continuous internal resonance of the human constitutive structure within its own concentration (Simondon, 2005).

Thymisou sōma (body, remember): toward the end of his life, the imperative of Cavafy (1992) poignantly invokes that of the flesh.

Observation and “Information”

Living phenomena when being observed are altered, for what is observed is not the essence of reality, but rather the reality of what is observed. “To observe,” from the Latin, ob-servare, means to adapt.

Modern “civilization,” raised upon the cult of its patent visibility, of which the secular society is the corner-stone, is the first in history to exclusively project itself onto its own immanent existence (Calasso, 1994, 2014a,b). “You are about to enter a world where the recording of an event eclipses the event itself,” anticipated Joseph Brodsky 25 years ago (Brodsky, 1995).

The invisible presence intrinsic to origin's recognition being superseded—extraneous to and separated from the internal-Self—the modern individual-observer no longer inscribes his/her subjective experience in the world, but rather in the incessant reception of data whereas the indefinite interface of the network unhinges the temporality and function of spaces. For an increasing number of people most activities are conducted by passive reception of stimuli; numberless inputs ‘organize’ the arc of our actions, inputs that rule and on our behalf shred in fragments the internal order in the flow of our days and dissipate any spontaneously organized activity or skill.

In the process of conforming an ancestral scheme of perception to new cognitive schemes and behavioral structures, the loss of visual attention is the peak moment of a vast genealogy, a genealogy wherein the overturning of visual experience begins with the passage from geometrical to physiological optics (17th and 18th centuries).

As extensively outlined by Crary (1992), to understand the fission between the internal Being and the projection of the individual onto the world it is necessary to examine the causes of the reversal of terms in the relation presence-vision during the last two centuries. In the visual culture of the 19th century, the new optical equipment applied to new forms of mass entertainment introduced realistic effects that were based on a radical abstraction and reconstruction of the visual experience. Thus, removed from the incorporeal relations of the camera obscura, the visual phenomenon is subsequently re-located in the human body. The rise of new production and disciplinary needs generates the necessity of parameters that enable the study of individual behaviors, in which the observer becomes object of observation, experimentation and normalization (Crary, 1992). Throughout the 20th century increasingly passive and instrumental forms of attention codify the activity of the eye through unaware responses (Benjamin, 1955) to stimuli, leading to the progressive eclipse of the immediate surroundings.

“Man's signs and structures are records because, or in so far as, they express ideas separated from, yet realized by, the process of signaling and building” (Panofsky, 1970). The multiplication of signs and the dematerialization of images generate perceptive dimensions transcending human wavelength wherein the presence of the observer no longer corresponds to its position in space.

Today's simultaneousness is a make-shift replacing the visual presence with “parallel temporalities” of illusory forms of human interaction and “social integration” (Crary, 1992, 2001). The awareness of the “bio-deregulation” (Brennan, 2003) induced by the perceptual leveling of dependency on information and communication systems that the technological imperative imposes (Stiegler, 2009) is the first step toward the preservation of the Freedom of the person, the human heritage of cultural identity and historical memory.

Project Humanum®: The Archaeology of Light

The project reconsiders the dialectic between the terms vision–presence in the contemporary perception of the figuration of archaic human statuary according to the transcendent meaning of its immaterial legacy.

As both object and subject the term humanum addresses the relationship between matter and its living dimension, “this de facto vision and the ‘there is’ which it contains” (Merleau-Ponty, 1964). The statue exists as a tangible form of the invisible. Its aspect, intrinsic to a latent transformation, is an attribute of my perception (Merleau-Ponty, see Johnson, 1993), it does not participate in the definition of its volume if I am able to envisage its different relief (Bergson, 1934) in a photograph, a planar surface by definition. Phôs-graphı, light-script, a scalpel to carve shadows whereas mimesis only casts the “sign” of an internal identification, photography can no longer be intended as a replica of what is already a reflection.

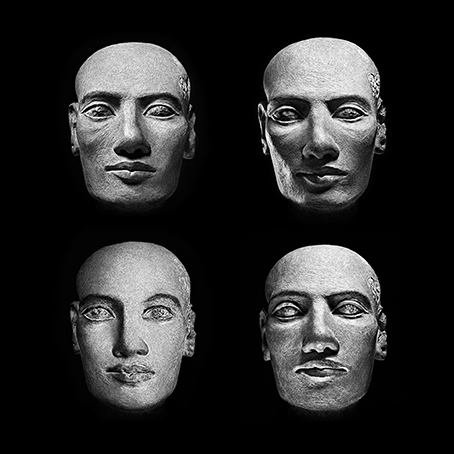

By means of a photo-mechanic process that fathoms the metamorphosis of the statuary form within the evolution of light, the Humanum process reveals to the viewer's eyes the endless transfiguration of the invisible aspects that surface over the sculpted matter. A selection of different images (modules) of the head of one same ideotype is thus organized by visual ensembles named Paradeigma. Each Paradeigma is composed by multiple modules—one-to-one size—of the original sculptural piece (Figures 2–4). To each module corresponds a negative silver matrix. Each Paradeigma constitutes an analog-digital structure encompassing multiple original negative matrixes; the quantity of modules is equal to a number multiplied by itself.

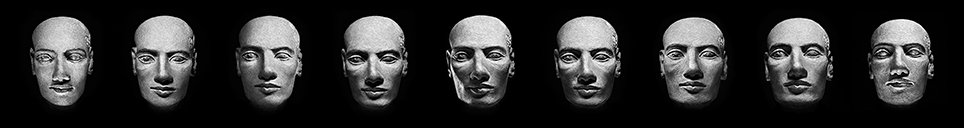

Figure 2. Head of Man Ca. 2289, known as Tête Salt, painted limestone, estimated Middle Empire 18th–20th century BC possible provenance Karnack, High Egypt Department of Egyptian Antiquities Musée du Louvre, Paris, France, Humanum® Paradeigma Frieze F9 dimension 1 to 1, 27.54 × 207 cm, Giorgia Fiorio © 2015.

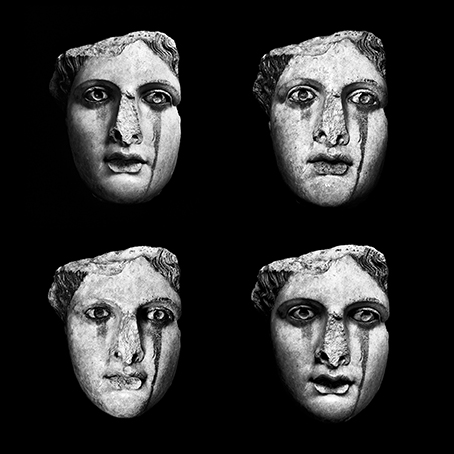

Figure 3. Female Head Nam. 244, Parian Marble, 2nd CE Acropolis Museum of Athens, Greece, Humanum® Paradeigma Square Q4 dimension 1 to 1, 81 × 81 Giorgia Fiorio © 2012.

Figure 4. Head of Man Ca. 2289, known as Tête Salt, painted limestone, estimated Middle Empire 18th–20th century BC possible provenance Karnack, High Egypt Department of Egyptian Antiquities Musée du Louvre, Paris, France, Humanum® Paradeigma Square Q4 C-1 dimension 1 to 1, 52.2 × 52.2 cm, Giorgia Fiorio © 2015.

In the simultaneous comparison among different appearances of one same physiognomy (Gombrich, 1961, 1999; Hochberg, 1972) the alteration of the perceptual constancy provoked by the immutable sculptural evidence and the transformation of its human countenance induce a vigilance bond that, received by the retina, induces the re-positioning of the focal fixation (Arnheim, 1969b) and the iterative confrontation between different images. In this process, the transformation of the visible appearance is underpinned once again by the awareness of an intrinsic recognition. Such inner-outer dialectic discloses the model, unique to each viewer's eyes only, that is, the gesture of the thought that generates the subject's internal projection of perception and the sign of each vision.

At the height of the process that unhinged the semantic relationship between the observer and reality, the Humanum® project aims to re-transcribe the status of the human archetype—today merely seen as codified sign of a static vestige of the past—into the dialectic idea of origins as living heritage of the future. The project investigates the principle in which the original comes to light; it questions the invisible model of a representative arché disclosing an endless ‘apparent’ morphogenesis in the evolution of a luminous impulse.

The objective of the project is the transcription of such intuition into different languages and spheres of research. A model from an aesthetic canon to a scientific parameter and reverse, reconstituting a form of representation and exposition aiming to visualize different combinations of knowledge, interconnected by codified systems of signs and similar semantic foundations.1 Humanum® aspires to re-establish the interiorization of the visual experience according to the resonance of its dynamic principle and to elicit the awareness of the urgency of a scientific resilience in the evolution of technology.

Author Contributions

GF explores the condition between reality and appearance in the relationship between matter and figure. Questioning the consciousness of subjective experience beyond the manifestation of the visible, the project Humanum® reconsiders the dialectic between the terms vision-presence in the perception of human figuration according to the immaterial heritage of archaic human statuary. In progress in collaboration with Ca' Foscari University of Venice the Humanum the project encompasses so far a first archaic series in Greece at the National Archaeological Museum of Athens; one head piece (2nd CE) at the Acropolis Museum of Athens; an Egyptian stone head (18th–20th century BC) at the Musée du Louvre where it will have the first exhibition from June 2017 and a Sumerian marble head: the “Lady of Warka” (32nd century BC) at the National Museum of Iraq in Baghdad.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

1 ^Since 2013 Humanum® project develops a parallel scientific research on related themes in collaboration with: Ca' Foscari University of Venice; L. Milano, Chair of History of the Antiquity and Near East Department of Humanities, Ca' Foscari University of Venice; G. Barbieri, Chair of History of Art and Cultural Heritage, Department of Philosophy and History of Art, Ca' Foscari University of Venice; M. Bergamasco, Chair of Robotics of Perception and M. Carrozzino, PhD in Virtual Reality and Computer Science of the Percro Laboratory, Scuola Superiore Sant'Anna; A. Schnapp, Chair of Classic Archaeology, National Institute of History of Art INHA, Paris; V. Stoichita, Chair of History of Art and Archaeology, Freiburg University (Switzerland); F. Vercellone Chair of Aesthetic Philosophy and Intra-University Morphology group of Turin University.

References

Agamben, G. (2005). Potentialities: Collected Essays in Philosophy. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. 181.

Aristotle (1933). Metaphysics. Book IV, with an English Translation by H. Tredennick (Cambridge, MA; London: Harvard University Press (Loeb Classical Library)), 1037, a30–32.

Arnheim, R. (ed.). (1969a). “The intelligence of visual perception (II),” in Visual Thinking, ed R. Arnheim (Berkeley; Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press), 37.

Arnheim, R. (1969b). “Fixation solves a problem,” in Visual Thinking (Berkley; Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press), 23–26.

Benjamin, W. (1936). Das Kunstwerk im Zeitalter seiner technischen Reproduzierbarkeit. Zeitschr. Sozialforsch. V, 1935–1939.

Bergson, H. (1914). “Life and consciousness,” in Huxley Memorial Lectures to the University of Birmingham (Birmingham: Cornish Bros.), 99–128.

Bergson, H. (1934). “La vie et l'œuvre de Ravaisson,” in La Pensée et le Mouvant, ed H. Bergson (Paris: Felix Alcan), 264–265.

Butler, S. (1900). The Odyssey: Rendered into English Prose for the Use of Those Who Cannot Read the Original. London: A.C. Fitfield.

Calasso, R. (1994). The Ruin of Kasch. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. 211.

Calasso, R. (2014a). Ardor, New York, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 88 (Chāndogya Upanisad 4.10.3, 4.10.5), 89 (Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upaniṣad 5.1.1; Upaniṣad 3.12.7-9), 119 (Ṝgveda I.164.20).

Calasso, R. (2014b). The Last Superstition (René Girard's Lectures). Stanford Arts Lectures, November 2014 (La superstition de la société, Cycle des conférences René Girard, Paris, Centre Pompidou, 2014).

Cavafy, C. (1992). Collected Poems, Translated by E. Keeley, and P. Sherrard (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press), 84.

Chāndogya Upanishad (1921). 6, 8, 7, V 1. The Thirteen Principal Upanishads, ed R. E. Hume (London: Oxford University Press).

Changeux, J.-P. (2004). “Thinking matter,” in The Physiology of Truth (London: Harvard University Press), 23–38.

Coomaraswamy, A. K. (1986). “The intention,” in Selected Papers, 1. Traditional Art and Symbolism (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press).

Coomaraswamy, A. K. (1997). “Imitation, expression, participation,” in The Door in the Sky: Coomaraswamy on Myth and Meaning, with a preface by R. P. Coomaraswamy (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press), 68.

Crary, J. (1992). “Modernity and the problem of the observer,” in Techniques of the Observer: On Vision and Modernity in the 19th Century (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press), 1–24.

Crary, J. (2001). “Modernity and the problem of attention,” in Suspensions in Perception: Attention Spectacle and Modern Culture (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press), 11–44.

Damasio, A. (2010). Self Comes to Mind: Constructing the Conscious Brain. New York, NY: Pantheon Books. part II, chap. 3.1.

Didi-Huberman, G. (2000). Devant le Temps. Histoire de l'art et Anachronisme des Images. Paris: Les Editions de Minuit (Collection Critique).

Diels, H., and Kranz, W. (1903). Fragmente der Vorsokratiker Griechisch und Deutsch. Leipzig: Weidmännische Buchhandlung. 119.

Freeman, W. J., and Vitiello, G. (2006). Nonlinear brain dynamics as macroscopic manifestation of underlying many-body field dynamics. Phys. Life Rev. 3, 93–118. doi: 10.1016/j.plrev.2006.02.001

Freeman, W. J., and Vitiello, G. (2010). Vortices in brain waves. Intern. J. Mod. Phys. B 24, 3269–3295. doi: 10.1142/S0217979210056025

Freeman, W. J., and Vitiello, G. (2015). Matter and Mind are Entangled in EEG Amplitude Modulation and its Double. Berkeley, CA: University of California (preprint): Available online at: www.researchgate.net/publication/290428630_Matter_and_Mind_are_Entangled_in_EEG_Amplitude_Modulation_and_its_Double_Preprint_Univty_California_at_Berkeley_CA_USA

Gibson, J. J. (1986a). “Looking with the head and eyes,” in The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception, ed J. J. Gibson (Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates), 207.

Gibson, J. J. (1986b). “The difference between the animal environment and the physical world,” in The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception, ed J. J. Gibson (Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates), 8–12.

Gibson, J. J. (1986c). “The ambient optic array,” in The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception, ed J. J. Gibson (Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates), 65–68.

Gibson, J. J. (1986d). “Pictures and visual awareness,” in The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception, ed J.J. Gibson (Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates), 270–271.

Gombrich, E. H. (1961). “Limits on likeness,” in Art and Illusion: A Study in the Psychology of Pictorial Representation (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press), 284–288.

Gombrich, E. H. (1999). “Pleasure of boredom,” in The Uses of Images. Studies in the Social Function of Art and Visual Communication (London: Phaidon Press), 214–215.

Gregory, R. L. (1990). The Eye and the Brain: The Psychology of Seeing. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. 64.

Guénon, R. (1995). “The idea of the center in the traditions of antiquity,” in Fundamental Symbols The Universal Language of Sacred Science, Compiled and edited by M. Vâlsan, translated by A. Jr. Moore (Oxford: Alden Press Ltd.), 45–53.

Guénon R. (2001). The Multiple States of the Being (Collected Works of René Guénon), translated by H. Fohr (Hillsdale, NY: Sophia Perennis), 33.

Guénon, R. (2002). The Reign of Quantity and The Signs of The Times (Collected Works of René Guénon), translated by Ld Northbourne (Hillsdale, NY: Sophia Perennis), 16–17.

Heidegger, M. (2005). Grammaire et Étymologie du mot “être.” Introduction en la Métaphysique, Translation by G. Kahn (Paris: Editions du Seuil (Original edition: Einführung in die Metaphysik. Tübingen: Max Nyemeyer Verlag, 1953).

Heisenberg, W. (1958). “Quantum theory and the structure of matter,” in Physics and Philosophy. The Revolution in Modern Science, Vol. 15, ed W. Heisenberg (London: Allen & Unwin (Unwin University Books, World Perspectives)), 129.

Hochberg, J. (1972). “The representation of things and people,” in Art, Perception and Reality, eds E. H. Gombrich, J. Hochberg, and M. Black (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press), 47–93.

Ibn ‘Arabī, M. (2006). The Universal Tree and the Four Birds, Translation by A. Jaffray (Oxford: Aqua Publishing).

Jaynes, J. (1995). “The diachronicity of consciousness,” in Consciousness: Distinction and Reflection, ed G. Trautter (Naples: Bibliopolis), 179–191.

Johnson, G.A. (1993). The Merleau-Ponty Aesthetics Reader. Philosophy and Painting (Studies in Phenomenology and Existential Philosophy), Translated by M. B. Smith (Evanston: Northwestern University Press), 126.

Joyce, J. (2012). Ulysses. London: Alma Classics Editions (Odissey Press Edition, 1939), part I; Nestor, I-8, 30.

Kerényi, K. (1979). “The Meaning of the Term ‘Mysteria’,” in The Mysteries. Papers from the Eranos Yearbooks, Vol. 2, ed J. Campbell (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press), 32–59.

Lagerwey, J. (2003). “Ecriture et corps divin en Chine,” in Corps des Dieux, eds C. Malamoud and J.-P. Vernant (Paris: Éditions Gallimard), 383–385, 392–393.

Libet, B. (2004). “Intention to act: do we have free will?” in Mind Time: The Temporal Factor in Consciousness (Cambridge, MA; London: Harvard University Press), 123.

Lucretius (2008). De Rerum Natura: The Latin Text of Lucretius, eds W. E. Leonard and S. B. Smith (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press), Liber IV 724–731.

Macrobius (2011). Saturnalia, Edited and translated by R. A. Kaster (Cambridge, MA; London: Harvard University Press (Loeb Classical Library)), 1–238.

Maspero, G. (1893). Études de Mythologie et D'archéologie Égyptiennes. Paris: Ernest Leroux Editeur.

Onians, R. B. (ed.). (1951a). “Cognition. The five senses,” in The Origins of European Thought: About the Body, the Mind, the Soul, the World, Time and Fate (Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press), 66–83.

Onians, R. B. (ed.). (1951b). “The ,” in The Origins of European Thought: About the Body, the Mind, the Soul, the World, Time and Fate (Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press), 93–122.

Onians, R. B. (ed.). (1951c). “Tλoç,” in The Origins of European Thought: About the Body, the Mind, the Soul, the World, Time and Fate (Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press), 426–466.

Pindar (1997). “Olympian odes,” in Pythian Odes, Edited and translated by W. H. Race (Cambridge, MA; London: Harvard University Press Loeb Classical Library), 56.

Plato (1892a). “Cratylus,” in The Dialogues of Plato, Translated into English, with Analyses and Introduction, Vol. 5, 401b ed B. Jowett (Oxford: Clarendon Press), 138–140; 668c (voulisis).

Plato (1892b). “Phaedrus,” in The Dialogues of Plato, Translated into English, with Analyses and Introduction, Vol. 5; 225d ed B. Jowett. (Oxford: Clarendon Press), 247a.

Plato (1892c). “Laws,” in The Dialogues of Plato, Translated into English, with Analyses and Introduction, Vol. 5, ed B. Jowett (Oxford: Clarendon Press).

Plato. (2007). Timaeus and Critias, Translated by B. Jowett, Introduction by O. Makridis. New York, NY: Barnes & Noble, 34a–36b, 38b.

Saint Thomas Aquinas (1947–8). Summa Theologiae. Translated by Fathers of the English Dominican Province. New York: Benziger Bros. Pars prima. Quaestio 84. Articulus 1 (416): Utrum anima cognoscat corpora per intellectum; Articulus 2 (417): Utrum anima per essentiam suam coporalia intelligat.

Simondon, G. (2005). L'individuation à la Lumière de Notions de Forme et d'Information. Paris: Editions Jérôme Millon. chap. 1, III-2, 63.

Simondon, G. (2014). Imagination et Invention, 1965–1966. Paris: PUF–Presse Universitaire de France.

Vernant, J. P. (1996a). “De la présentification de l'invisible à l'imitation de l'apparence,” in Mythe et pensée chez les Grecs. Études de psychologie historique (Paris: Editions La Découverte (La Découverte Poche/Sciences humaines et sociales, 13), 340–343.

Vernant, J. P. (1996b). “La figure du corps,” in Mythe et Pensée chez les Grecs. Études de psychologie historique. (Paris: Editions La Découverte (La Découverte Poche/Sciences humaines et sociales, 13), 347–349.

Vernant, J. P. (2003). “Corps de hommes, corps des dieux,” in Corps des Dieux, eds C. Malamoud and J. P. Vernant (Paris: Gallimard (Collection Folio Histoire, 120)), 20–33.

Vitiello, G. (2001). “My double myself,” in My Double Unveiled, the Dissipative Quantum Model of Brain: Advances in Consciousness Research (Amsterdam: John Benjamins Pub. Co.), 140–145.

Keywords: presence in visual perception, human archetype, living matter, inner consciousness, semantic memory

Citation: Fiorio G (2016) The Ontology of Vision. The Invisible, Consciousness of Living Matter. Front. Psychol. 7:89. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00089

Received: 22 November 2015; Accepted: 15 January 2016;

Published: 23 February 2016.

Edited by:

Isabella Pasqualini, Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne, SwitzerlandReviewed by:

Carlo Ventura, University of Bologna, ItalyGiuseppe Vitiello, University of Salerno, Italy

Copyright © 2016 Fiorio. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Giorgia Fiorio, giorgia@555studios.net

Giorgia Fiorio

Giorgia Fiorio