Abstract

Philosophers have applied the framework of constitutive grounds to make sense of the disagreement between subjectivism and objectivism. The framework understands the two theories as being involved in a disagreement about the extent to which value is determined by attitudes. Although the framework affords us with some useful observations about how this should be interpreted, the question how value can be determined by attitudes in the first place is left largely unanswered. Here we explore the benefits of a positive interpretation which aims to address this oversight and make the framework more informative. This interpretation, which is inspired by the recent work of Schroeder (2007) and Sobel (2016), claims that the relevant sense in which value can be determined by attitudes is discovered by seeing how facts can be endowed with the normative property of being a reason. We argue that this interpretation significantly deepens our understanding of the disagreement between subjectivism and objectivism.

Similar content being viewed by others

On one understanding, subjectivism is the view that value is determined by attitudes and objectivism is the view that denies that this is so.Footnote 1 There are many other ways of spelling out the two theories, but this general understanding appears to capture something of importance.Footnote 2 For it takes subjectivism and objectivism to be very general theories about the nature of value. Philosophers have recently used the framework of constitutive grounds in an attempt to clarify the disagreement between the two theories even further (Rabinowicz and Rønnow-Rasmussen 2000; Rønnow-Rasmussen 2003; Brännmark 2002; Fritzson 2014).Footnote 3 The framework of constitutive grounds provides a pattern of analysis whereby subjectivism and objectivism can be given negative characterizations. When applied to subjectivism, it yields a theory consisting of the following claims:

-

1.

Objects only have value in so far as they are targeted by attitudes, but neither attitudes nor attitude-satisfaction need have value.Footnote 4

-

2.

Features are only value-makers in so far as they are the features for which objects are targeted by attitudes, but neither attitudes nor attitude-satisfaction need be value-makers.Footnote 5

To hold that these claims are true is to hold that attitudes serve as the constitutive grounds of value, either by themselves or in conjunction with something else.Footnote 6 Proponents of objectivism deny that the claims are true, because they think that attitudes need not be present for objects to have value or for features to be value-makers.Footnote 7 The framework of constitutive grounds promises to capture at least three important aspects of the disagreement between subjectivism and objectivism: The first is that the theories are in a disagreement over whether value is ultimately determined by the presence of attitudes; the second is that the theories are neutral about the substantive issue of which objects are valuable, and what makes objects valuable; the third is that the theories are neutral in regards to which types of values there are.

The worry is that the framework of constitutive grounds only manages to capture the aforementioned aspects by saying too little. We want to understand what theories like subjectivism are committed to when they claim that value is determined by the presence of attitudes. The framework of constitutive grounds suggests that value is determined by the presence of attitudes without attitudes being bearers of value or the things that make objects good or bad. We would suggest that this is only marginally illuminating, for the question remains what else the disagreement between subjectivism and objectivism could possibly be about: How else might we understand the role that is played by attitudes when they serve as the constitutive grounds of value? How is the determination spoken of by subjectivism to be understood?

In what follows we explore a positive interpretation of the framework of constitutive grounds that aims to answer this question. This interpretation is derived from the combination of two different views about value and reasons: The first represents an old tradition, founded by Franz Brentano (1889/1969) and resurrected by Thomas Scanlon (1998), which says that value reduces to the presence of reasons. The tradition is referred to as the “Buck-Passing Account of value” (hereafter abbreviated as the ‘BPA’). The second view is a more recent development, defended by philosophers like Mark Schroeder (2007) and David Sobel (2016), according to which subjectivism and objectivism are in a disagreement over the features in virtue of which facts are reasons. We believe that the combination of these seemingly disparate views can afford us with a deeper understanding of the commitments of subjectivism and objectivism.

When we interpret the framework of constitutive grounds, we will often end up talking of features making a property or being the features in virtue of which a property is instantiated. The question how we should understand such notions is a difficult one that we cannot hope to answer here. What we can say is that we take them to involve the phenomenon of some properties being explained by other properties. This explanatory relation is hyperintensional and asymmetric, since it involves the assignment of metaphysical priority to at least one relatum. For this reason, we believe it to be what some philosophers have in mind when they talk about grounding (e.g. Bliss and Trogdon 2016) and possibly what others have in mind when they talk about resultance (Dancy 2004: 85–86).Footnote 8 All of this will become clearer momentarily, as we begin to illustrate the relation in question with substantive examples.

1 The Constitutive Grounds of Value

On the framework of constitutive grounds, subjectivism holds that attitudes serve as the constitutive grounds of value and objectivism denies that this is necessarily so. Exactly what it means for attitudes, or anything else, for that matter, to serve as the constitutive grounds of value, is almost never explicated. Instead, proponents of the framework have so far tended to illustrate it through the use of metaphors and analogies, the precise understanding of which is seldom straightforward. For example, at one point in their early discussions of the framework, Rabinowicz & Rønnow-Rasmussen attempt to clarify its basic points by way of the following analogy involving the game of chess:

[T]hat a certain move in chess is admissible is a feature that supervenes on the internal properties of the move and of the situation on the chess-board. But the constitutive grounds of its being admissible are to be found in something external—in our conventions that determine the game of chess. Similarly, according to some preferentialist conceptions of value, preferences or attitudes may bestow a value on the object towards which they are directed. Still, if the object is being preferred for the features that are internal to it, then this externally constituted value is intrinsic: it supervenes on the internal properties of the object, precisely those properties for which the object is being preferred (2000: 37).

It is important to note that constitutive grounds are not to be understood in terms of the mereological concept of constitution. To suggest that attitudes serve as the constitutive grounds of value, then, is not equivalent to saying that a piece of mud is constitutive of a statue, that agency is constitutive of personhood, or that a mixture of rum and coke is constitutive of a Cuba Libre. Neither proponents of subjectivism or objectivism need have any view about what constitutes value in this mereological sense. This means that the chess analogy might be somewhat misleading, since it is unclear whether the conventions determining the game of chess are not even partly constitutive of the game itself in a manner similar to these. Nevertheless, the analogy might still be helpful in the formulation of some general observations about the behavior of constitutive grounds.

Proponents of subjectivism claim that favoring knowledge ultimately determines that knowledge is good. Yet no value accrues to attitudes or the satisfaction of attitudes. It is also not the case that favoring knowledge necessarily makes knowledge good. Proponents of subjectivism would explain this pattern roughly as follows: If someone asked us to explain what makes knowledge good, we would probably point to some of the features that knowledge has. Perhaps knowledge is good in virtue of its pragmatic property of making our lives go better or in virtue of its intrinsic property of being constituted by a true and justified belief. These are commonly the features for which knowledge is favored. Once we go beyond them and start talking about the broader role played by attitudes themselves, we have stepped outside of the substantive domain and ventured into the more abstract realms of axiology.

The same point can be made by using the chess analogy, as long as we are given enough leeway. Whenever we consider a certain chess move, the impact of the move on the situation of the board is likely to be among the features to figure in the foreground of our minds, while the broader conventions that determine the game of chess itself are relegated to the background.Footnote 9 When asked to explain why we have made one chess move rather than another, we will be much more likely to formulate our explanation in terms of the impact of the move on the situation of the board. Once we go beyond this and start talking about the more general conventions that determine the game of chess, there is an important sense in which we are no longer answering questions that are asked within the context of a particular game of chess, as much as we are answering questions about the game of chess itself.

Another important observation that will prove relevant later on concerns the modal character of constitutive grounds, which can be brought out by considering a common objection to the theory of subjectivism. There is a worry that when we consider a possible world featuring a different distribution of attitudes, we will be forced to conclude that, in that possible world, there will also be a different distribution of values. To many this might seem like an absurd consequence that casts doubt on the validity of subjectivism. The framework of constitutive grounds allows for attitudes to serve as the constitutive grounds of value across possible worlds (Rabinowicz and Rønnow-Rasmussen 2000: 37; Rønnow-Rasmussen 2003: 258; Fritzson 2014: 71–80).Footnote 10 That we favor knowledge in our world ensures that knowledge is valuable in whatever world it is to be found.Footnote 11

Once again, the same point can be made by using the aforementioned analogy involving the game of chess. Imagine a possible world where people like to play a game that they refer to as ‘chess’, determined by conventions that are widely different from those that determine the game we refer to as ‘chess’. It seems clear that even though we both use the term ‘chess’, the games we are talking about when we use that term are potentially very different from one another. If they are different enough it might even make sense to say, given our particular perspective, that the game of chess is never really played in that possible world. This means that constitutive grounds could be taken to have a modal character of a very rigid nature, their influence stretching beyond the confines of the specific worlds where they are found.Footnote 12

There is much else that could be said about the framework of constitutive grounds as it is typically described, especially about its relation to other theories and historical traditions within axiology. Here we will have to make do with the brief descriptions of the structural and modal features of the framework, since these appear to be the most important. Indeed, the framework of constitutive grounds seems to be all about structure and modality, as its primary purpose is to carve out conceptual space for a type of relation that is then never properly explicated. To reiterate, this relation is meant to explain how things like attitudes can play a central role for value in whatever world it is to be found, but without being the features that value accrues to or the features in virtue of which it accrues. The way in which this is accomplished, however, seems to us rather unsatisfying.

2 Towards a Positive Interpretation

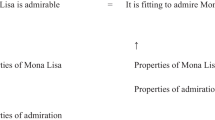

The first key to unlock the interpretation we have in mind involves the BPA, which understands value in terms of the presence of reasons.Footnote 13 The idea is that for an object to be good is for there to be reasons to favor the object, while for an object to be bad is for there to be reasons to disfavor the object. Different kinds of values will be analyzed in terms of different kinds of attitudes: The value of being admirable is to be understood in terms of there being reasons for admiration; the value of being respectable is to be understood in terms of there being reasons for respect; and so on. This understanding is used here for the clarity and simplicity that it affords the interpretation we have in mind. We shall return to its disadvantages in the next section, where we consider objections to the interpretation we are about to formulate.

We take reasons to consist of facts, understood here as obtaining states of affairs. States of affairs are recognized as being entities with a propositional character, capable of being picked out by that-clauses. That Keanu Reeves is sad is a clear example of a fact that is also a reason. For those who are able, perhaps the fact is a reason to cheer up Keanu Reeves. This is to suggest that the fact that Keanu Reeves is sad has the normative property of being a reason. The distinction between reasons and the normative property of being a reason is important. When philosophers deny that reasons are part of the furniture of the world, they need not deny the existence of facts. Instead, what they have to deny is that the normative property of being a reason is ever actually instantiated.Footnote 14

Philosophers might want to deny that the normative property of being a reason is ever instantiated on account of it being very difficult to come to grips with its relations and dependencies. It is a commonplace to observe that whenever a normative property is instantiated, there must be some explanation as to why this is so. When an object is valuable or a fact is a reason there must be something else in virtue of which the object is good or bad. We are of course allowed to be uncertain about what explains the instantiation of the normative property of being a reason. Figuring out what affords a fact with its normative status is not always going to be easier than, say, figuring out exactly what makes knowledge good. Nevertheless, we know that there must be something in the fact that could potentially do the explaining.

The second key to unlock our interpretation is afforded by philosophers like Schroeder (2007: 23-34) and Sobel (2016: 17, 117), who are among those to defend the view that attitudes are in some sense responsible for making facts reasons. The ways in which they cash out this general claim differ and so there is some unclarity as to whether they really share the same understanding of the relation they appeal to. We shall not concern ourselves with the details here, but try to find inspiration in the general claim as it appears. On the interpretation we have in mind, subjectivism states that attitudes are necessarily among the features in virtue of which facts are endowed with the normative property of being a reason. Objectivism could be taken to deny that this is so, since there are cases where attitudes are absent from the features that afford facts with their normative status.Footnote 15 To illustrate let us next reconsider the value of knowledge.

Knowledge is extrinsically good in virtue of the pragmatic property of being able to make our lives go better.Footnote 16 The fact that knowledge has the pragmatic property is the reason to favor knowledge. The fact that knowledge has the pragmatic property must be a reason in virtue of something else. Subjectivism claims that what affords the fact in question with the normative property of being a reason is the presence of attitudes. More specifically, the role of constitutive grounds is played by the favoring of knowledge. The fact that knowledge has the pragmatic property ends up being a reason, then, precisely because the pragmatic property is among the features for which knowledge is favored. Proponents of objectivism deny all this and claim that features not involving attitudes can help explain how facts such as this end up being reasons.

Suppose next that knowledge is intrinsically good in virtue of the property of being constituted by justified and true beliefs. The fact that knowledge has the intrinsic property is the reason to favor knowledge. The fact that knowledge has the intrinsic property must be a reason in virtue of something else. Again, subjectivism claims that what affords the fact with the normative property of being a reason is the presence of attitudes. More specifically, the role of constitutive grounds is played by the favoring of knowledge. The fact that knowledge has the intrinsic property ends up being a reason precisely because the intrinsic property is among the features for which knowledge is favored. Proponents of objectivism would deny all this and claim that features not involving attitudes can explain how facts come by their normative status. If the interpretation we offer is right, then it becomes clear why subjectivism is not committed to saying that attitudes are the object that value accrues to or the features that make objects good or bad. What attitudes do is endow certain facts with the normative property of being a reason.Footnote 17

Proponents of subjectivism might be reluctant to accept that there are reasons for attitudes. This would presumably stem from the worry that attitudes would then fail to be prior to the normative. It is important to note that this does not follow from the interpretation we offer. If an object is not favored, and we have no other attitudes that commit us to favoring the object, then there are also no reasons to favor the object. Only once the object is targeted by attitudes are we given reasons and so attitudes are in fact prior to the normative. Of course, this commits subjectivism to a form a bootstrapping, but this is an old worry for the theory. According to subjectivism, everything that we favor is endowed with some kind of value. Proponents of subjectivism can either accept the bootstrapping result or try to restrict the set of attitudes that are meant to be normatively relevant.Footnote 18 We see it as a benefit that the interpretation we offer does not settle the issue of how this, or any other problems facing subjectivism, ought to be dealt with.

Some philosophers have feared that the truth of subjectivism would be incompatible with the possibility of intrinsic value (e.g. Moore 1922: 269; Korsgaard 1983:174). The thought is roughly that if value is determined by the presence of attitudes, then that means that value must be instantiated in virtue of the presence of attitudes as well. As a result, no object can have value in virtue of its intrinsic features alone. The framework of constitutive grounds is meant to allow for subjectivism and objectivism to be neutral about what makes objects have value. This benefit is obviously preserved by the interpretation that we have afforded the framework. To reiterate, this interpretation only commits subjectivism and objectivism to a story about what makes facts reasons, not what makes objects good and bad.

3 Against the Positive Interpretation

We want to understand what theories like subjectivism are committed to when they claim that value is determined by the presence of attitudes. According to the interpretation we offer, this should ultimately be understood in terms of attitudes making facts reasons. The nature of the making relation remains deeply mysterious, to be sure, but its involvement in this context still involves a theoretical gain. For in addition to the negative characterization given to us by the framework of constitutive grounds, we now have a positive story to tell. This story entails that the determination spoken of by subjectivism is no longer treated as a mere placeholder ensuring that subjectivism can remain neutral about what the bearers of value are and what makes objects good or bad. In other words, we now have a deeper understanding of precisely why subjectivism can remain neutral in these regards.

We wish to consider some of the objections that the interpretation we offer is faced with. One problem concerns the modal character of constitutive grounds. In the earlier section, constitutive grounds were described as potentially being very rigid in nature, their influence stretching beyond the confines of the specific worlds where they are to be found. The objection might be made that this does not fit well with the interpretation we have laid out. The intuition is that when a value or normative property is instantiated in a world, this cannot be in virtue of features that are not also in that same world. If this is right, then there seems to be a significant discrepancy between the relation we have in mind and the relation that is meant to be of relevance to the framework of constitutive grounds. So the latter could not plausibly be understood in terms of the former, or so the objection goes.

An obvious response would be to simply insist on the possibility that is denied here, that a fact can have the normative property of being a reason in virtue of features that it is modally separated from. The interpretation we have laid out results in a version of subjectivism which states that facts are endowed with their normative status by the presence of attitudes. This is a coherent view and it seems equally coherent to suppose that a proponent of the view might go a step further and claim that the presence of attitudes can make facts reasons in whatever worlds they are to be found. We may certainly doubt the truth of such a claim, but it being false would cast no doubt whatsoever on the validity of the interpretation at hand, as much as it might cast doubt on the theory of subjectivism. We are not sure what else to say here that does not risk turning the discussion into a mere table-thumping over intuitions.

Another objection insists that the interpretation we offer does not avoid the result that subjectivism and objectivism are theories about what makes objects valuable. Suppose an object has value in virtue of there being certain facts present, and these facts are relevant in so far as they are afforded their normative status by attitudes, then transitivity guarantees that there is a general sense in which the object has value in virtue of the presence of said attitudes.Footnote 19 We think that this is right as far as it goes, but this general sense is not the one we should have in mind. Value-makers are to be identified with the things we would first point to when asked to explain why an object has value. To reiterate, these are the facts that constitute reasons for attitudes. The explanatory bases figuring at a lower level of the hierarchy, explaining why the facts are reasons for attitudes to begin with, play a less direct role and so do not constitute value-makers. We think this way of partitioning things does not just reflect how we conduct our evaluative talk and practices, but captures the way in which all makers of properties are ordinarily treated.Footnote 20

Perhaps the most serious objection against the interpretation we offer concerns the assumption that value can be understood in terms of the presence of reasons. The literature is filled with alleged counterexamples that cast doubt over this assumption. More specifically, they aim to show that there can be reasons to favor objects that are not good, just like there can be reasons to disfavor objects that are not bad. The standard counterexample was first formulated in the discussions of Crisp (2000) and involves an Evil Demon that forces people to admire worthless things.Footnote 21 If threatened by violence and torture, agents can be given reasons to favor something like a saucer of mud, even if it is assumed to lack any value whatever. This is the wrong-kind of reasons problem (hereafter referred to as the ‘WKR-problem’) and it has been met with countless responses over the past fifteen years or so.

One of the most discussed strategies for dealing with the WKR-problem relies upon a distinction between evaluative reasons and practical reasons (Skorupski 2010).Footnote 22 Evaluative reasons call for us to have certain attitudes, while practical reasons call for us to commit certain actions. The idea here is that when agents are forced to admire worthless things, they are not given evaluative reasons to have certain attitudes, but rather practical reasons to avoid being punished by the Evil Demon. At best, these practical reasons amount to a recommendation on part of the agents to somehow cause themselves to have the relevant attitudes. Another popular strategy is to accept that the Evil Demon does give us evaluative reasons, but claim that the reasons are of the wrong kind (Rabinowicz and Rønnow-Rasmussen 2004; Olson 2004; Stratton-Lake 2005; Hieronymi 2005; Lang 2008; Way 2012). This response involves a challenge on part of its proponents to distinguish reasons of the right kind from reasons of the wrong kind.

Given the degree of sophistication that discussions over the WKR-problem have reached, it becomes difficult to hold even a brief discussion here. Instead, we wish to acknowledge that the assumption that value is reducible to the presence of reasons is a highly controversial one. On the other hand, the degree to which the counterexamples constitute a genuine problem for the interpretation at hand is not clear. The assumption that value is reducible to the presence of reasons has been primarily motivated by a regard for simplicity and clarity. In addition, it was meant to unify the interpretation we have in mind, making it simultaneously applicable to value and reasons. One way of responding to the objection would be to point out that the assumption is not required in order to get some version of the interpretation to work. If we are skeptics with regard to the reduction of value to the presence of reasons, we could insist that the former is nonetheless explainable by reference to the latter. The idea is that if an object is valuable, then the object is valuable in virtue of there being reasons for attitudes.

The view that wherever there is value there must also be reasons for attitudes is not formally subject to the kinds of counterexamples typically used to illustrate the WKR-problem. After all, the counterexamples are meant to show that although there can be reasons for attitudes, there are cases where these reasons to not correspond to any value. This is perfectly compatible with the weaker account under consideration, although certain aspects of the WKR-problem certainly remain to be addressed. If we claim that only some reasons for attitudes give rise to value, then there is still a challenge on our part to say something about what unites them. In other words, we would still need to offer a distinction between reasons of the right kind and reasons of the wrong kind. The difference is that this challenge would now constitute a general normative problem, rather than a strict formal objection against the account in question.

One potential problem is that the weaker account is not in agreement with the BPA about what constitutes value-makers. In response to the transitivity worry, we noted that value-makers are those factors we would first point to when explaining the presence of value. The BPA therefore implies that value-makers are to be found among the facts that we identify as reasons for attitudes. By contrast, the weaker account implies that value-makers are to be found among facts about there being reasons for attitudes. This means that knowledge can no longer be said to be made good by the fact that it has certain pragmatic properties, but has to be good in virtue of the fact that there are reasons to favor knowledge.Footnote 23 This result may strike some of us to be too revisionary. Even if we manage to accommodate the intuition that neither attitudes nor attitude-satisfaction need be value-makers, then, it might be argued that the weaker account fails to be sufficiently neutral in regards to what else could play this role.

This brings us to the last objection which we would like to consider which concerns the neutrality which is meant to characterize the disagreement between subjectivism and objectivism. There are two different issues here which may cause concern, one conceptual and one substantive. Even those who agree that value has a strong connection to reasons might feel uncomfortable with the use of such views in the present context.Footnote 24 The intuition is that to understand the disagreement between subjectivism and objectivism, we should not have to invoke conceptual theses of this kind. Subjectivism and objectivism are meant to be entirely neutral with regard to how we should understand the connection between value and reasons. The interpretation we have laid out does not manage to fully accommodate this intuition.

As we have just seen, a similar worry crops up from a more substantive point of view. The interpretation we have laid out places the disagreement between subjectivism and objectivism outside one substantive area of enquiry where it does not belong. It allows for proponents of the two theories to agree on what has value and what makes objects have value. The disagreement is instead taken to be about what makes facts reasons. The objection is that a plausible interpretation should also allow proponents of subjectivism and objectivism to agree on this issue. More generally, the intuition is that subjectivism and objectivism are meant to be outside any and all substantive areas of enquiry (Rønnow-Rasmussen 2003: 251–253). Again, the interpretation we have laid out does not manage to fully accommodate this intuition.

It seems reasonable to suppose that theories cannot be informative and yet neutral with regard to all substantive and conceptual issues. However, we agree that neutrality in regards to the specific issues just mentioned would still be preferable. The fewer controversial assumptions theories manage to make while remaining informative the better (cf. Rønnow-Rasmussen 2003: 251–253). This invites a response to the objection in the form of a counterchallenge: That the interpretation we have laid out fails to be neutral with regard to some conceptual and substantive issues could be seen as a disadvantage either of the framework of constitutive grounds or the interpretation itself. If the interpretation is to be abandoned, some alternative ought to be presented, or neutrality is once again won at the cost of informativity.

The interpretation developed here ensures that when proponents of subjectivism and objectivism are pressed, as they sometimes are, on how to best understand the relation between value and attitudes, they can do more than explain what the relation is not. We acknowledge that some will find the price of these benefits to be too high. With the exception of Schroeder and Sobel, perhaps, we expect that most will insist that the interpretation is, for one reason or another, not in line with the spirit of either subjectivism or objectivism.Footnote 25 We are more sympathetic to this feeling than appearances might suggest. We hope that what we have said here will encourage said philosophers to say something more constructive about constitutive grounds than they have done so far. If there is some alternative interpretation waiting to be discovered, which manages to be informative and neutral, we will welcome it with open arms.

4 Conclusions

The framework of constitutive grounds carves out conceptual space for a relation that, quite frankly, no one seems to have a good grasp of. In this paper we have tried to deepen our understanding by offering a positive interpretation of the framework in question. The interpretation relies upon a hyperintensional and asymmetric relation that, although not without its own share of mysteries, is already in full use in axiology and elsewhere. In this sense, the interpretation we have laid out makes the framework of constitutive grounds a good deal less obscure. Our main concern has been to clarify the disagreement between subjectivism and objectivism in a way that captures three important aspects: The first is that the theories are in a disagreement over whether value is ultimately determined by the presence of attitudes; the second is that the theories are neutral about the substantive issue of what objects are valuable and what makes objects valuable; the third is that the theories are compatible with the possibility of intrinsic, as well as extrinsic, value. In the end, then, we might not be in a position to establish the truth of either subjectivism or objectivism, but at least we know where the truth is more likely to be found.

Notes

It is important to note that attitudes are here referenced as a placeholder for a broad category of motivational and non-doxastic mental states, including desires, preferences, passions, admiration, respect, love, disgust, loathing, indignance, hate, and so on. Favoring will be understood as an activity involving attitudes of a distinctly positive sort, while disfavoring will be understood as an activity involving attitudes of a distinctly negative sort.

According to another understanding, subjectivism and objectivism are theories about what facts constitute reasons for action (e.g. Williams 1973/1981; Parfit 2011). While the former claims that reasons for action are facts about attitudes, the latter denies that this is necessarily so. On another common understanding, subjectivism and objectivism are theories about what objects are valuable (e.g. Moore 1922: 255–257; Korsgaard 1983: 172–173; Kagan 1998: 281–282; Parfit 2011: 45). While the former claims that preference satisfaction is good, the latter denies that this is so. Subjectivism and objectivism also occur as labels in a more metaethical context, where they are sometimes taken to disagree about the meaning of value statements (e.g. Hare 1981: 76; Bar-On and Chrisman 2009: 133; Jackson 1998: 114; Miller 2003: 36; Shafer-Landau 2003: 18). While the former is claims that value statements are used to express or give reports about the attitudes of speakers, the latter denies that this is so. Now, since they are meant to be general theories about the nature of value, the types of subjectivism and objectivism that we concern ourselves with here are meant to be neutral with regard to these sorts of issues.

The framework was first developed in order to distinguish between two different versions of preferentialism (Rabinowicz and Österberg 1996).

Objects are hereafter understood in a general sense, as anything that can conceivably be a bearer of value. On a liberal view of value-bearers, objects may be concrete individuals, facts, states of affairs, events, processes, structures, properties, relations, and so on.

Again, attitudes and the satisfaction of attitudes only make objects valuable in so far as they are also among the features for which the objects are favored.

Actually, objectivism could be understood as the view that attitudes are sometimes the constitutive grounds of value or as the view that attitudes are never the constitutive grounds of value. Subjectivism can likewise be understood as the view that attitudes are the only constitutive grounds of value or as the view that attitudes are always among the constitutive grounds of value. We believe that the choice between these different versions of the theories will turn out to be largely irrelevant to the issues at hand.

There are many competing accounts of how grounding is to be understood, some of which are closer to the relation we have in mind than others. The relation we have in mind is meant to be pluralistic in the sense that its relata can belong to different ontological kinds. While some philosophers tend to understand grounding as a relation that holds between all manner of objects (Cameron 2008; Schaffer 2009), others claim that grounding only holds between facts (e.g. Rosen 2010: 109; Audi 2012: 691; Sider 2012: ch 8), while others are more liberal. What makes matters more difficult is that still other philosophers distinguish between grounding that is metaphysical and grounding that is normative (e.g. Fine 2012; Bader 2016). For the purpose of this paper, we do not feel the need to come down on one side or the other on this issue. Some accounts of grounding make it similar to the relation we have in mind, but we leave it up to others to decide which label would be most appropriate here.

In his discussions about subjectivism, Fritzson (2014: 41-51) puts a lot of emphasis on objects figuring in the foreground or the background of evaluations.

Against this line of response it may be insisted that attitudes other than the ones we actually have could have been our own. If we consider the attitudes in other possible worlds and treat them as if they were actual, then we would have to conclude that other objects would also be valuable. (This way of treating possible worlds has become increasingly common in the philosophy of language, especially possible-world semantics, where it has been used in the development of a two-dimensional approach to meaning (e.g. Jackson 1998, 2004; Chalmers 1996, 2004, 2006). Proponents of subjectivism could here respond in one of two ways: They might claim that attitude is determined by the presence of idealized attitudes and these cannot be different from what they are; they might also claim that although treating possible worlds as if they are actual may have its uses, it goes against the spirit of subjectivism to take this perspective when it comes to value (Rønnow-Rasmussen 2003: 259). Even if these responses are successful, it may be argued that subjectivism is left vulnerable to a related but somewhat different problem. The problem is that if the distribution of either idealized or actual attitudes turn out to be different from what we assume, then the distribution of values will, accordingly, also be different (Huemer 1996: section 4; Fritzson 2014: 78–79).

However, as Fritzson (2014: 74-75) notes, it can easily happen that actual attitudes become sensitive to the attitudes in possible worlds. We may not favor an abundance of ice-cream in possible worlds where no one has any positive attitudes towards ice-cream.

In the case of chess the rigidity of constitutive grounds is arguably a result of the workings of language and the fixed nature of terms like ‘chess’. In the case of value the rigidity of constitutive grounds is not meant to be explained in this way. The framework of constitutive grounds is about the nature of value, not about the meaning of evaluative terms (Rabinowicz and Österberg 1996: 25–26; Fritzson 2014: 190).

Distinguishing reasons from the normative property of being a reason also requires us to be careful in the way we express ourselves. Some philosophers, like Scanlon, occasionally suggest that properties could themselves give us reasons (1998: 97). Given the assumptions we are making, this could mean one of two things: one interpretation is that the fact that certain objects have those properties are reasons (Väyrynen 2006: 296: n3); another is that the properties in question serve as part of the makers of the property of being a reason. The very same ambiguity crops up whenever philosophers choose between saying that facts give us reasons and that certain facts are reasons. Some philosophers, like Parfit, suggest that the manner of speaking we employ here is inconsequential (2011: 32). We believe that it might not be. For while it is true that both claims could be taken to mean that facts are reasons, saying that facts give us reasons could also mean that they too figure as makers of the property of being a reason.

Proponents of objectivism will disagree about the issue about why facts come to be endowed with the normative property of being a reason. What brings them together is merely the view that attitudes are not necessarily among the features in virtue of which facts are endowed with the normative property of being a reason.

Perhaps this is not all. The features for which objects are favored are the features in virtue of which the objects are good or bad. This seems ambiguous between two different readings, either a motivational one or a justificatory one. On the one hand, features may be the things for which an object is favored, meaning that they motivate the favoring of the object. On the other hand, features may also be the things for which an object is favored, meaning instead that they justify favoring the object. We are unsure about this, but it may well be that proponents of subjectivism and objectivism disagree about which of these readings is correct. Suppose subjectivism adopts a motivational reading. This would have the result that anything that motivates the favoring of objects, no matter how inconsequential it may seem to the value of said objects, can end up being a value-maker. That a person feels pain can be a value-maker for the desirability of her torture, in so far as her torturer desires her torture for the pain that the person feels. Suppose instead that subjectivism adopts a justificatory reading. This would result in questions about how we should understand the nature of the justification. On one understanding, to say that a favoring is justified is to say that there are reasons to adopt the favoring. Here there is an obvious risk of circularity and infinite regress and so new avenues for arguments and objections are opened up.

Thanks are owed to an anonymous reviewer for bringing this to our attention.

In fact, we would rather deny the transitivity of the relevant relation, than face the conclusion that value-makers occur all the way down the explanatory hierarchy.

There is another way of formulating our explication. The BPA does not assign the role of value-maker to anything explicitly normative, in so far as it states that what makes knowledge good is simply the fact that knowledge has certain pragmatic properties. This fact would not be a value-maker if it did not constitute a reason, to be sure, but its being a reason is not also a value-maker. By contrast, the weaker account does assign the role of value-maker to something explicitly normative, in so far as it states that what makes knowledge good is the fact that there are reasons—which, as it happens, are constituted by the fact that knowledge has certain pragmatic properties. Indeed, the weak account claims that value-makers must include normative components in this way, which is potentially a problem.

Thanks are owed to an anonymous reviewer for pressing this issue.

One such reason that we have not had occasion to mention concerns motivation. Proponents of subjectivism might regard the once close and attractive connection between reasons and attitudes, which affords us with a neat account of moral motivation, to be more spurious on the interpretation we have laid out. For a discussion of this issue, see (Schroeder 2007: ch. 8–9).

References

Audi P (2012) Grounding: toward a theory of the in-virtue-of relation. J Philos 109(12):685–711

Bader R (2016) Conditions, modifiers, and holism. In: Lord E, Maguire B (eds) Weighing Reasons. Oxford University Press, New York, p 27–56

Bar-On D, Chrisman M (2009) Ethical Neo-expressivism. In: Shafer-Landau R (ed) Oxford Studies in Metaethics, vol 4. Oxford University Press, Oxford, p 133–165

Beardsley MC (1965) Intrinsic Value. Philos Phenomenol Res 26(1):1–17

Bliss R, Trogdon K (2016) Metaphysical grounding. In: Zalta EN (ed) The Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy (Winter 2016 Edition). https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2016/entries/grounding/

Brännmark J (2002) Morality and the pursuit of happiness: a study in Kantian ethics. Doctoral dissertation, Lund University

Brentano F (1889/1969) The origin of our knowledge of right and wrong (2nd trans: Chisholm R, Schneewind E). Routlege, London

Cameron RP (2008) Turtles all the way down: regress, priority and fundamentality. Philos Q 58(230):1–14

Chalmers DJ (1996) The conscious mind: In search of a fundamental theory. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Chalmers DJ (2004) Epistemic two-dimensional semantics. Philos Stud 118(1):153–226

Chalmers DJ (2006) The foundations of two-dimensional semantics. In: Garcia-Carpintero M, Macia J (eds) Two-dimensional semantics. Oxford University Press, Oxford, p 55–140

Crisp R (2000) Review of ‘value ... And what follows’ by Joel Kupperman. Philosophy 03:452–452

Dancy J (2004) Ethics without principles. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Fine K (2012) Guide to ground. In: Correia F, Schnieder B (eds), Metaphysical Grounding. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, p 37–80

Fritzson FA (2014) Value grounded on attitudes. Subjectivism in value theory. Doctoral dissertation, Lund University

Gertken J, Kiesewetter B (2017) The right and the wrong kind of reasons. Philos Compass 12(5):12:e12412

Hare RM (1981) Moral thinking: its levels, method, and point. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Heuer U (2011) Beyond wrong reasons: the Buck-passing account of value. In: Brady MS (ed) New waves in metaethics. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke, p 166–184

Hieronymi P (2005) The wrong kind of reasons. J Philos 102(9):437–457

Huemer M (1996) The Subjectivist’s dilemma. Objectivity 2(4):77–92

Jackson F (1998) From metaphysics to ethics: a Defence of conceptual analysis. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Jackson F (2004) Why we need A-intensions. Philos Stud 118(1):257–277

Kagan S (1998) Rethinking intrinsic value. J Ethics 2(4):277–297

Korsgaard C (1983) Two distinctions in goodness. Philosophical Rev 92(2):169–195

Lang G (2008) The right kind of solution to the wrong kind of reason problem. Utilitas 20(4):472–489

Miller A (2003) An introduction to contemporary Metaethics. Polity Press, Cambridge

Moore GE (1922) The conception of intrinsic value. In: Philosophical studies. Routledge & Kegan Paul, London, p 253–275

Olson J (2004) Buck-passing and the wrong kind of reasons. Philos Q 54(215):295–300

Parfit D (2001) Rationality and reasons. In: Egonsson D, Petersson B, Josefsson J, Rønnow-Rasmussen T (eds) Exploring practical philosophy: from action to values. Ashgate, Aldershot, p 17–39

Parfit D (2011) On what matters: volume one. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Persson I (2007) Primary and secondary reasons. In: Egonsson D, Josefsson J, Petersson B, Rønnow-Rasmussen T (eds) Homage à Wlodek: philosophical papers dedicated to Wlodek Rabinowicz. Ashgate, Aldershot, p 19–39

Rabinowicz W, Österberg J (1996) Value based on preferences. Econ Philos 12(01):1–27

Rabinowicz W, Rønnow-Rasmussen T (2000) A distinction in value: intrinsic and for its own sake. Proc Aristot Soc 100(1):33–51

Rabinowicz W, Rønnow-Rasmussen T (2004) The strike of the demon: on fitting pro-attitudes and value. Ethics 114(3):391–423

Rønnow-Rasmussen T (2003) Subjectivism and objectivism. Patterns of value; essays on formal axiology and value analysis I. Conference proceedings, Lund University

Rosen G (2010) Metaphysical dependence: grounding and reduction. In: Hale B, Hoffmann, A (eds) Modality: metaphysics, logic, and epistemology. Oxford University Press, Oxford, p 109–136

Scanlon TM (1998) What we owe to each other. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Schaffer J (2009) On what grounds what. In: Manley D, Chalmers D, Wasserman R (eds) Metametaphysics: new essays on the foundations of ontology. Oxford University Press, Oxford, p 347–383

Schroeder MA (2007) Slaves of the passions. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Shafer-Landau R (2003) Moral realism: a defense. Clarendon Press, Oxford

Sider T (2012) Writing the book of the world. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Skorupski J (2010) The domain of reasons. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Smith M (1994) The moral problem. Blackwell, Oxford

Sobel D (2016) From valuing to value: a defense of subjectivism. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Stratton-Lake P (2005) How to deal with evil demons: comment on Rabinowicz and Rønnow-Rasmussen. Ethics 115(4):788–798

Väyrynen P (2006) Resisting the Buck-passing account of value. In: Shafer-Landau R (ed) Oxford Studies in Metaethics vol. 1. Oxford University Press, Oxford, p 295–324

Way J (2012) Transmission and the wrong kind of reason. Ethics 122(3):489–515

Williams B (1973/1981) Internal and external reasons. In: Moral Luck: philosophical papers 1973–1980. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, p 101–113

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Garcia, A.G., Green Werkmäster, J. Subjectivism and the Framework of Constitutive Grounds. Ethic Theory Moral Prac 21, 155–167 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10677-018-9862-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10677-018-9862-1