Notes

An example of a string that is deviant both syntactically and semantically is Chomsky’s (1957, p. 15) (i). At the opposite end, (ii) is plausibly deviant for reasons that are neither syntactic nor semantic but instead because it instantiates center embedding, which creates processing difficulties. (i) Furiously sleep ideas green colorless. (ii) The milk that the boy that the dog chased bought spoiled. Chomsky (1957) is well aware of the messy relationship between intuitive unacceptability and syntactic ill-formedness. His advice is to build the simplest possible grammar that gets the facts right for the clear cases, and then let the grammar itself decide about the cases that are not clear. While I agree that there is some room for theory-driven decisions of this sort, the notoriously problematic case of polarity phenomena, which will be the focus of this review, presents an interesting situation, in that its relationship to grammar has been illuminated only via intense and focused study over several decades, and is still hotly debated.

A prejacent is a proposition that a propositional operator (such as only) combines with and operates on.

14 is based on what’s found in LiG, p. 34, footnote 14. To make it more easily understood, though, I have contraposed the material implication and added disambiguating parentheses.

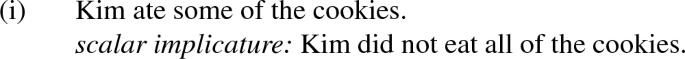

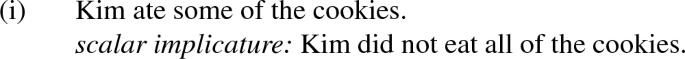

A scalar implicature is an inference underpinned by the use of an expression that is less informative than some comparable expression that could have been used instead. For example, sentences with some are less informative than (i.e., asymmetrically entailed by) minimal counterparts with all instead of some. This leads to scalar implicatures like (i).

In a tradition extending from Grice (1967), with important updates by Horn (1989), scalar implicatures are standardly analyzed as defeasible pragmatic inferences (conversational implicatures) resulting from general cooperative principles of conversation, in particular Grice’s Maxim of Quantity, which enjoins speakers to be as informative as is required. The choice to use a less informative expression (like some) is thereby taken to indicate that the more informative expressions (like all) would have yielded a false statement. A secondary goal of LiG (see in particular LiG section 2.3) is to argue instead that scalar implicatures are derived in compositional semantics, via the workings of alternatives and exhaustification.

As defined by LiG (p. 66): “A function f is anti-additive ...iff for any A and any B, f(A \(\vee \) B) \(\Leftrightarrow \) f(A) \(\wedge \) f(B).”

In possible worlds semantics, a modal base is the set of contextually supplied accessible worlds over which a modal expression (like can or must) quantifies.

This is not to say that the nonveridicality approach to NPI licensing is unassailable. For example, an anonymous reviewer points out that disjunction is nonveridical (p or q entails neither p nor q), and yet disjunction does not typically license NPIs. According to Giannakidou (2011 and earlier work), there is in fact an NPI in Greek licensed by disjunction; moreover, NPIs not licensed by disjunction “may also contain other lexical properties that will place additional factors [aside from nonveridicality –TG] in determining [their] distribution” (2011: 1697). See Giannakidou 2011 and references therein for further discussion.

Sauerland acknowledges that, after the publication of his note, he learned that the same point was made earlier by Jon Gajewski in a 2009 handout, where the observation is attributed to Danny Fox.

Del Pinal (2019) implies that because ident(himself\(_{1}\)) is a predicate, it admits rescaling. While this might help with (56-b), the trace in (56-a) is not a predicate but rather a bound variable. See also follow-up work by Chierchia (Forthcoming), who argues, in a spirit similar to Del Pinal’s, that logical forms can be modulated by “replacement functions” (cf. Del Pinal’s rescale operator) that target content words and variables (bound pronouns and traces), “whose values range on the denotations of content words” (p. 16).

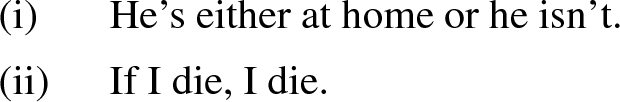

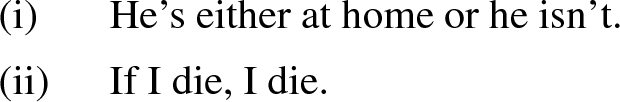

An anonymous reviewer points out that some kinds of acceptable tautologies seem to have “almost conventionalized pragmatic uses,” such as conveying speaker ignorance, as in (i), or speaker indifference, as in (ii).

While both of these kinds of examples are technically assimilable under Del Pinal’s approach (and the latter even under LiG’s approach, since it relies on two tokens of die), it is not so clear that rescaling is the right way to understand their pragmatic effect.

There are three other post-LiG works in this vein that I cannot resist advertising: Abrusán (2019) carries out an excellent overview of issues in the relationship between semantic anomaly, pragmatic infelicity, and intuitive unacceptability. Mayr (2019) applies Chierchia’s proposal in explaining why know can embed interrogative clauses (“John knows whether Mary smokes”) but believe cannot (“*John believes whether Mary smokes”). Giannakidou and Etxeberria (2018) review experimental approaches to characterizing and differentiating sources of intuitive unacceptability.

References

Abrusán, M. (2019). Semantic anomaly, pragmatic infelicity, and ungrammaticality. Annual Review of Linguistics, 5, 329–351.

Barker, C. (2018). Negative polarity as scope marking. Linguistics and Philosophy, 41, 483–510.

Chierchia, G. (2006). Broaden your views: Implicatures of domain widening and the “logicality” of language. Linguistic Inquiry, 37, 535–590.

Chierchia, G. (2013). Logic in Grammar: Polarity, Free Choice, and Intervention. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Chierchia, G. (Forthcoming). On being trivial: Grammar vs. logic. In: Sagi, G., Woods, J. (eds.), The Semantic Conception of Logic: Essays on Consequence, Invariance, and Meaning, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Chierchia, G., & Liao, H. C. D. (2015). Where do Chinese wh-items fit? In L. Alonso-Ovalle & P. Menendez-Benito (Eds.), Epistemic indefinites: Exploring modality beyond the verbal domain (pp. 31–59). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Chomsky, N. (1957). Syntactic Structures. Mouton: The Hague.

Dayal, V. (2009). Variation in English free choice items. In R. Mohanty & M. Menon (Eds.), Universals and Variation: Proceedings of GLOW in Asia VII. Hyderabad: EFL University Press.

Del Pinal, G. (2019). The logicality of language: A new take on triviality, “ungrammaticality”, and logical form. Noûs, 53, 785–818.

Fauconnier, G. (1975). Pragmatic scales and logical structure. Linguistic Inquiry, 6, 353–375.

Fox, D. (2007). Free choice disjunction and the theory of scalar implicatures. In U. Sauerland & P. Stateva (Eds.), Presupposition and Implicature in Compositional Semantics (pp. 71–120). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Gajewski, J. (2002). L-analyticity and natural language, ms., University of Connecticut.

Gajewski, J. (2011). Licensing strong NPIs. Natural Language Semantics, 19, 109–148.

Giannakidou, A. (1998). Polarity sensitivity as (non)veridical dependency. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Giannakidou, A. (2001). The meaning of free choice. Linguistics and Philosophy, 24, 659–735.

Giannakidou, A. (2006). Only, emotive factives, and the dual nature of polarity dependency. Language, 82, 575–603.

Giannakidou, A. (2011). Negative polarity and positive polarity: licensing, variation, and compositionality. In K. von Heusinger, C. Maienborn, & P. Portner (Eds.), The Handbook of Natural Language Meaning (2nd ed., pp. 1660–1712). Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Giannakidou, A. (2018). A critical assessment of exhaustivity for Negative Polarity Items. Acta Linguistica Academica, 65, 503–545.

Giannakidou, A., & Etxeberria, U. (2018). Assessing the role of experimental evidence for interface judgment: Licensing of negative polarity items, scalar readings, and focus. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1–18.

Grice, P. (1967). Logic and conversation, unpublished ms. of the William James Lectures, Harvard University.

Horn, L. R. (1989). A natural history of negation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Horn, L. R. (2016). Licensing NPIs: Some negative (and positive) results. In P. Larrivée & C. Lee (Eds.), Negation and Polarity: Experimental Perspectives (pp. 281–305). Switzerland: Springer.

Kadmon, N., & Landman, F. (1993). Any. Linguistics and Philosophy, 16, 353–422.

Krifka, M. (1995). The semantics and pragmatics of polarity items. Linguistic Analysis, 25, 209–257.

Ladusaw, W. A. (1979). Polarity sensitivity as inherent scope relations, PhD dissertation, University of Texas at Austin.

Lahiri, U. (1998). Focus and negaitve polarity in Hindi. Natural Language Semantics, 6, 57–125.

LeGrand, J. (1975). ‘or’ and ‘any’: the syntax and semantics of two logical operators, PhD dissertation, University of Chicago.

Linebarger, M. C. (1987). Negative polarity and grammatical representation. Linguistics and Philosophy, 10, 325–387.

Mayr, C. (2019). Triviality and interrogative embedding: context sensitivity, factivity, and neg-raising. Natural Language Semantics, 27, 227–278.

Romoli, J. (2012). Soft but strong. Neg-raising, soft triggers, and exhaustification, PhD dissertation, Harvard University.

Rooth, M. (1982). Association with focus, PhD dissertation, University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

Rooth, M. (1992). A theory of focus interpretation. Natural Language Semantics, 1, 75–116.

Sauerland, U. (2017). A note on grammaticality and analyticity. Snippets, 31, 22–23.

Schwarz, B., & Simonenko, A. (2018). Factive islands and meaning-driven unacceptability. Natural Language Semantics, 26, 253–279.

Szabolcsi, A., & Zwarts, F. (1993). Weak islands and an algebraic semantics for scope taking. Natural Language Semantics, 1, 235–284.

Vlachou, E. (2014). Review of Chierchia 2013, LINGUIST List 25.2210, https://linguistlist.org/issues/25/25-2210.html, retrieved 5/26/20.

von Fintel, K. (1999). NPI-licensing, Strawson-entailment, and context-dependency. Journal of Semantics, 16, 97–148.

Acknowledgements

For helpful comments and encouragement on earlier drafts of this review, I would like to thank Gennaro Chierchia, Larry Moss, and an anonymous reviewer. Of course, all remaining errors are my own.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Grano, T. Book Review. J of Log Lang and Inf 30, 633–656 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10849-021-09333-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10849-021-09333-y