Abstract

While facing cuts, downsizing and revenue losses, media organizations experience paradoxical demands in being organized for print or linear production with daily deadlines and simultaneously striving to be ‘digital first’ and produce and publish stories online on a continuous basis throughout the day. In this paper, we describe efforts applied when introducing the metaphor flowline in a medium-sized newspaper organization in Norway with the aim of aligning their production and publishing processes to readers’ consumption of online news. Both the production volume of journalistic content, reader consumption and the newsroom workers’ experience of mastering their everyday work life increased dramatically in a very short time. The involvement of a temporary autonomous team in the planning and designing of a test pilot aiming to make flowline “as practice”, was integral to the digital transformation success, allowing for participative action across newsroom boundaries. Based on the empirical findings from the local newspaper organization and drawing on theories on liminality (Turner 1982, 1986) and metaphorical work (Schön 1993), this article presents a set of six interrelated steps incorporating a structure for autonomous teams and their role in enabling lasting change in organizations facing digital transformation.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

How do you enable change in an industry that has been operating in more or less the same way for forty odd years? The major digital transition that has changed the global media business in colossal, and for many even catastrophic ways, has had particular impact on newspaper organizations. As they have mainly adhered to the principles of print journalism, with its traditional modes of producing an editorial (printed) newspaper within a fixed deadline, this ‘digital revolution’ has to a large extent implied having to explore, develop and adapt to new and different ways of producing and distributing news, more often than not without generating satisfying revenue for survival. Primarily, this is related to the need to adhere to the still continuously emerging principles of online journalism, which involves ongoing news production on multiple digital platforms. While much emphasis is placed on newspapers’ requirements to adjust and adapt to, as well as to continue to develop for, the digitally infused media future, the major basis of income for most newspapers today is still the sale of printed editions of the paper.

Media organizations thus experience paradoxical demands in being organized for print or linear production with daily deadlines and simultaneously striving to be ‘digital first’ and produce and publish stories online on a continuous basis throughout the day. The discrepancies between these two modes of news production are reflected not merely in terms of their lived temporality, i.e. linear vs. non-linear, but also in terms of the types of knowledge and competence applied and acknowledged, work practices, tools and platforms for production and distribution, as well as their business models. The introduction of digital publishing has brought on continuous metrics measurements that instantly reveal the success of each individual story, e.g. the journalist’s and digital desk worker’s combined effort in making people not only click on, but actually read their stories online.Footnote 1 Newspaper journalists normally operate in an individually autonomous work mode, whereas team efforts have largely been the domain of the desk and graphics department. In rare circumstances, they collaborate in a major investigative journalism team, something that minor or medium-sized new organizations rarely can afford, particularly after repeated downsizing the past decade due to major revenue losses. Autonomous teams charged with a mandate to change the internal work process, is thus something of an invention in this industry. As will follow from the discussion below, we argue that the structures allowing for autonomous teamwork is necessary for successful digital transformation within such traditional domains.

Instead of solely focussing their time, efforts and competence towards becoming the ‘digital newspaper of tomorrow’, newspaper organizations must continue to manage and adhere to both logics and modes in their everyday news production. The organizing of news production throughout the workday and the metaphorical language describing work tasks, roles and responsibilities, are thus by and large designed for deadline production and signal to everyone involved that this is still comme il faut and what gives status. Precisely due to the many discrepancies that can be identified in terms of competences, work practices, production tools and deadlines, newspaper employees perceive their workday as largely characterized by a constant struggle to manoeuvre between these two modes of production that can be seen as symptoms of two diverging logics: the linear (print) and the non-linear (digital). Even though a more predictable and less stressful workday is appreciated it is not straight forward to mobilize the individually autonomous journalists for collective change based on shared meaning.

The toolkit news workers have available to deal with these new challenges are to a large extent the same as they used during the time of ‘print only’ and is rarely designed for teamwork. This only adds to their experience of ambiguity, since the internalized professional maps they carry do not fit that well with the new media terrain. The established notion of what it implies to be a journalist, or news worker, and what it implies to be producing news, seems to be especially hard to challenge. It is deeply embedded both in the professional identities of the news workers themselves, as well as in the societal, organizational and institutional context of news production (see Ryfe 2012; Petre 2015; Christin 2014 on what gives legitimacy and status in the media industry).

To assist media organizations in making the shift towards an open-ended near future-oriented work flow, three newspapers were invited to participate in an action research project for creative collaboration, co-construction of metaphors and intervention in newsrooms initiated by the authors and our colleagues. In this article, we describe the efforts which we as a part of this project applied with one of the media organizations towards the aim of aligning their production and publishing processes to readers’ consumption of online news. One major finding was how outdated the internal language of news production was with the current reality, and this prompted the researchers to introduce and co-develop new metaphors and concepts together with editors and staff representatives, among them the metaphor in question here, flowline. This metaphor indicated a different mode of production than the ‘deadline’ regime that was previously so defining for newspaper work.

The involvement and ownership of the ongoing change process in the newsroom by a dedicated small autonomous team of journalists, became integral to the organization’s efforts of inventing and adjusting flowline as practice. The team was composed during a workshop involving the newsroom staff and was given the task to come up with suggestions to concrete changes for the overall work flow. The mandate gave them authority to suggest and test incremental changes in their everyday work environment and also facilitated for their, i.e. the team’s, learning process to be integrated in the learning of the organization as a whole. After a 4 weeks pilot period of testing flowline “as practice”, the managers reported that the production volume and reader consumption increased dramatically, that is, 40 and 30% respectively, while the newsroom workers reported feeling less stressed, with strengthened experience of mastering their everyday work life. What were the factors that enabled this particular newsroom to not only manage the paradoxical demands of print and digital publishing, but also thriving in it, to the extent that they now, unlike most newsrooms, can actually claim to embody ‘digital first’ as an established, collective practice and mindset?

Drawing on experiences from a successful case in a local news organization, Moss Avis, in Norway, we here identify a series of minor measures or steps needed to achieve lasting change in organizations struggling to adapt to ongoing digital transformation. We focus on what measures are needed for changing the flow of production, organizational structure and workflow of news organizations, with an emphasis on how one can create lasting change in an organization where many of the employees are long-term staff, with a large degree of individual autonomy within strict managerial frames. The concept of liminality is applied as an analytical tool for breaking down the change process into various phases or ‘steps’, from the employees and managers experiencing external pressure to improve their results, towards internally motivated and initiated change processes. Further, we discuss how the (idea) work of autonomous teams contribute not only to the identification of needs and suggestions for measures taken, but also to the integration of lasting changes and innovations in the organization as a whole.

2 Liminality in organizations

It has been argued that radical change is only advanced in ‘unsettled times’ during ‘social upheaval’ (Swidler 1986), such as the still ongoing digital transformation in the media industry. In many ways, innovations within the industry are abundant, in terms of new content management solutions, analytical tools and production technologies. However, while the industry is most certainly in need of making innovations regarding development and use of technological equipment, user interfaces and audience interactions, such innovations lose some of their value and usefulness if the media newsrooms themselves are not able to use and implement these innovations into the structures and practices of their everyday work. Thus, one might argue that one of the main challenges for news organizations today is not the ability to come up with or embrace new ideas, concepts or innovations, nor is it a lack of new technological knowledge, but rather the challenges they face as they themselves attempt to make these innovations an integrated and established part of everyday work practices. Shifting the balance of producing news for the printed paper to digital publishing thus requires changes not only in the organizational structure, workflow and distribution of roles and responsibilities, but also for managers and employees to become more flexible and versatile in finding new and creative ways of collaborating (Bygdås et al. 2019).

As pointed out by Howard-Grenville et al. (2011) and Swidler (1986) individuals tend to use the strategies of action that work well for them, even if different, and potentially better, options are available, because new skills and habits require an effort to learn and apply in productive ways. Hence the proliferation of outdated practices in professions and business areas undergoing rapid change. In a situation where resources are becoming scarce, available time for learning limited and professional anxiety for the future high, finding prospects for better ways of producing news becomes a pressing issue. Simultaneously these factors are also what makes it challenging for employees and management to develop local well-functioning solutions (Bygdås et al. 2019). Using autonomous teams as a vehicle to mobilize the organization has been suggested as a means of producing innovative, and preferably ingenious, solutions (Hoegl and Parboteeah 2006). For news organizations that traditionally have been managed through strong, hierarchical and authoritative leadership granting autonomy only to the individual journalist, delegating leadership to a development team is not straightforward. One argument we often met, was that this shift in power could endanger the editorial responsibility and execution of ‘filling the paper’ with content in time of the printing press deadline (Bygdås et al. 2019).

Considering how a successful process of lasting change necessarily implies a transition from one condition to another, our approach is informed by theoretical perspectives on liminality. In studies of organizations the use of liminal theory has been applied to a wide range of settings such as identity construction (Beech 2011), temporary workers (Garsten 1999), organizational insiders (Howard-Grenville et al. 2011), consultants (Czarniawska and Mazza 2003; Sturdy et al. 2006), knowledge-sharing communities (Swan et al. 2015), and individual and organizational learning (Tempest and Starky 2004). As described by anthropologist Victor Turner (1986), a liminal phase constitutes a limited time period representing a transition from one status or condition to another (the pre-liminal and the post-liminal). Crossing a threshold, or limen, one enters into the “no man’s land betwixt and between the structural past and the structural future” (Turner 1986, p 41). One leaves the status quo, the indicative mood of ‘as is’, crossing the threshold into a temporary, out of the ordinary phase that Turner characterizes as “being dominantly in the subjunctive mood of culture, the mood of maybe, might be, as if, hypothesis, fantasy, conjecture, desire” (Turner 1986, p 42). The period spent in the subjunctive mood of liminality represents a process of change which is time limited, and from which one eventually returns, crossing the threshold back into ‘ordinary life’, albeit in a changed capacity.

Unlike “[o]rdinary life [which] is in the indicative mood, [and] where we expect the invariant operation of cause and effect, of rationality and commonsense” (Turner 1986, p 42), liminality is characterized by the simultaneous presence of the familiar and the unfamiliar, the existing and the new, which implies that it must be considered a fundamentally ambiguous condition. Such transitions are necessarily characterized by experiences of insecurity and discomfort, as one leaves the familiar behind to venture into new, untested waters, in which one’s well-established and embodied ways of doing things no longer apply to the same extent.

Part of the challenge for news organizations operating in the currently ‘unsettled times’ of the media industry, is that they find themselves in something of a liminal phase characterized by uncertainty, ambiguity, and thereby anxiety, does not seem to be ending any time soon, but rather seems to have become something of a permanent condition. The ambiguities that news organizations experience as they struggle to adhere to the logics of print and digital production simultaneously (and upon which their survival in the rapidly changing media industry necessarily depends), unavoidably also manifest themselves in the organization and workflow of the newsroom. The digitization of the newsroom is manifested not only in the online platforms that the news is published on, but also in the content management systems and recently in the metric evaluation systems. One might thus argue that the reluctance and inability of news workers to make (lasting) changes in their work practices and organization can be related to the underlying indication that this necessarily implies being subjected to additional liminality, and thus an even more present sense of ambiguity and discomfort. Not least because there are no guarantees that the changes made might actually improve their capabilities of producing news more efficiently, and thus help avoid further cost cuts and downsizings.

Liminality is here particularly useful as an analytical notion because “it specifically deals with transformatory learning processes during transition periods and boundaries (i.e. learning boundaries)” (Wagner et al. 2012, p 2). Beech further argues that liminality denote individuals as being both in a transitory state and as an experience “[o]f ambiguity and in-between-ness within a changeful context” (2011, p 4). In the liminal previous distinctions are becoming opaque, people are liberated from structural obligations and have no rights over others (Turner 1982; Czarniawska and Mazza 2003). While the liminal phase might be experienced as a form of negative ambiguity, it also holds the potential for new thinking. Turner emphasizes how liminality can be described as “a fructile chaos, a storehouse of possibilities, not a random assemblage but a striving after new forms and structures, a gestation process, a fetation of modes appropriate to postliminal existence” (Turner 1986, p 42). Similarly, Wagner et al. (2012) suggest that liminality offers a space where people are free from previous constraints helping them to produce novel solutions. By subjecting autonomous teams of news workers to recurring interactions as we will describe below, the research team could thus provide ‘pockets of liminality’ in which the employees might enter the subjunctive mood of culture—a place for fantasy, play, and hypothesis, where employees might imagine potential changes to be implemented. In order for a transition, or change, to be completed (and thus successful), the participants must also claim ownership and bring these new imagined practices back with them across the threshold returning to the post-liminal indicative mode of ordinary life in a changed capacity. The ‘what if’ must be transformed into the new ‘as is’.

Theories of change favour an approach of involvement, shared understanding and agreed upon solutions to make change happen (Greenwood and Hinings 2006). However, such approaches downplay how the novel resonates and fits in with the established norms, routines and practices (Levina and Orlikowski 2009). As argued by Feldman and Orlikowski (2011), perceiving change as something to be implemented rather than as a process of changing might lead to failure in achieving the proposed benefits. Suchman (2007, p 257) describes such a shift as moving from “an ontology of separate things that need to be joined together” to a worldview that “comprises configurations of always already interrelated, reiterated sociomaterial practices” (quoted in Feldman and Orlikowski 2011, p 257). As described in the introduction, we established early how central, and formative, the notion of the deadline (with its many connotations to the paper edition of the news) was for the work and production flow in media organizations. This is something of a paradox, since most journalist stories are written for online publication first, hence the mantra of ‘digital first’ that the majority of managers and editors-in-chief are voicing as the strategy for bringing in more revenue through digital subscriptions. As Schön (1993) argues, central terms and metaphors that characterize the everyday speech in an organization should not be underestimated when one is concerned with change. A well-established term such as the ‘deadline’ contributes to the cementation and reinforcement of existing work practices and production processes, which in turn can inhibit the potential for actual innovation and change (Morgan 1997; Srivasta and Barrett 1988).

According to Schön (1993), metaphors can also be generative. Imaginative and creative new metaphors can provide us with novel understandings of our experiences and everyday activity that are not available to us through our conventional framework of meaning (Lakoff and Johnson 2008, p 139–141). Such metaphors do not merely offer a different way of looking at things, but is also a “process by which new perspectives on the world come into existence” (Schön 1979/1993, p 137). In continuation of making the news organization’s employees and management aware of the extent to which the deadline metaphor was shaping and guiding their everyday news production, we introduced them to the new and generative metaphor of the flowline. The flowline metaphor provided the organization’s management and employees with the means through which they could imagine and enact other ways of doing things, and how they could bring it into everyday practice. It enabled them to imagine the new ‘as is’ that would follow from the transitional ‘what if’ as something that made sense, and that they could strive for rather than be afraid of.

In what follows, we describe our methodological approach and then present the six stage process model for sustainable change in organizations, using empirical examples and reflections of the employees in the local news organization following a pilot period of digital transformation. This is not a transformation from analogue to digital work modes, but from one way of producing digitally to a more work and cost-effective mode of digitized journalistic practices. With this process model as a point of departure, we will discuss various strategies that have, in close collaboration with the employees themselves, been brought forth to improve the everyday work situation in their news organization. The chosen mode of innovative inquiry and implementation is based on the notion that humans’ ordinary and extraordinary practices are central loci of organizing, and that it is through situated and recurrent activities that organizational outcomes are produced and become reinforced or changed over time. A special emphasis is placed upon how this strategic model implies empowering employees with the collective autonomy and confidence to suggest and implement changes based upon their embodied experiences of local challenges, and providing them with the creative abilities and tools to do so.

3 Research design

The action research project OMEN: Organizing for Media Innovation (2015–2019) was established by researchers at the Work Research Institute, OsloMet, Norway (authors included) with the aim of creating new insights on how to manage, organize and practice innovation and development in companies infused with the traditions, practices and legacy of the newspaper industry. We will here present some of the results of the OMEN project, in which we collaborated with three medium-sized Norwegian news organizations (one local, one regional and one national niche newspaper) to enable, initiate and facilitate local innovation and change processes, so that they could better face the difficulties they encounter in a currently turbulent media industry. This involved locally experimentation and (re)-design of workflows and organizing for interactions between different parts of the production system, including the relations between old and new technologies, rethinking of division of labour, and developing new forms of expertise.

The project’s research design is built upon an action research approach, in which practitioners and researchers engage in co-creation of practical solutions as well as knowledge for the research community (Reason and Bradbury 2006). This approach has been expanded upon with perspectives from ethnography, emphasizing the empirical advantages of conducting observations in situ of events and interactions as they unfold—i.e. ‘being there’ (Watson 1999), through participant observation. Inspired by principles from appreciative inquiry (Ludema et al. 2006) and positive organizational scholarship (Cameron et al. 2003), “[p]rimacy is given to transformative inquiries that involve action, where people change their way of being and doing and relating in their world—in the direction of greater flourishing” (Heron and Reason 2006, p 145). This implies that the researchers ask the questions, and instead of providing answers rather provoke answers from research participants—here employees and management in news organizations. Research participants have in a variety of variously sized temporary constellations (such as management only, employees only, or mixed groups of these, as well as across disciplinary borders of journalism, photography, metrics, editing, marketing, etc.) repeatedly been engaged in joint collaboration through workshop interventions facilitated by the researchers. These workshops have functioned as a main vehicle for exploring, experimenting and testing new concepts and work forms emerging from co-created understanding and analytical efforts, as well as functioning as a form of feedback workshops (Pettigrew 1990) contributing to the validation of findings and enhancement of construct validity (Yin 2003).

The decision to participate in the OMEN project was in all three news organizations made by the management, who identified a need for outside assistance in their efforts to change their organizations to thrive in the new media landscape. The researchers’ access to the newsroom and its employees, as well as the scheduling of and requirements of participation in workshops facilitated by the researchers, was thus decided and administrated by local management. While the researchers’ role was to facilitate for change in the newsroom, we did not enter the organizations with a pre-given ‘expert’ design to be implemented, but rather operated from a perspective that the local employees, including management, had to be considered genuine experts on their own (working) situations. All interventions designed and conducted were thus based upon or aimed towards gaining insights from journalists, other staff and managers, identifying the challenges they were facing, what changes they considered needed to be made, and ideas as to how. A main aim was to increase the level of innovation competence in the organization, so that the employees themselves would become more autonomous and independent in the development of new ideas that could be tested, experimented with and adjusted locally.

To gain an initial knowledge foundation for the research interventions, one of the first activities in the OMEN project was to conduct semi-structured interviews in all three news organizations with everyone in the newsroom (editors, journalists, photographers, desk journalists, marketers and receptionists), mapping out aspects of their everyday work through questions revolving around past experiences, reflections about the current situation and expectations for the future. Data from these interviews provided valuable insight into how employees were affected by the ongoing digital transformation in the local context of their organization. Accumulated insights obtained from such interactions with the research field, typically informed the topic for future interventions. Using self-developed visual awareness tools (Bygdås et al. 2019), the researchers would in workshops repeatedly bring observations and analyses back to the organizations, presented as semi-finished ideas, models or tools, with the aim of raising awareness about practices that remained unarticulated or taken for granted. By engaging and connecting employees and managers in shared reflection, imagination and creation around how problems and challenges can be dealt with, we anticipated that it would enable them to agree upon concrete measures to lower the threshold for testing new ways of working.

Between interventions, we have conducted follow-up interviews (formal and informal), performed participant observation in the newsroom, organized meetings with editors and staff, and held presentations and initiated discussions for the whole newsroom or groups of employees, including representatives of the corporate headquarter and editors of other local newspapers in their consortium (see Table 1 for details). We have also conducted a series of ‘sit-alongs’ (inspired by ‘walk-alongs’, see Holgersson 2014; Hagen et al. 2016, Bygdås et al. 2019), a methodological innovation developed through the OMEN project, where the researcher sits beside individual journalists while they are working on their computer, conversing about what they are doing in real time. In addition to feeding into the relevance of future workshop interventions, these combinations of methods were used to develop conceptualizations and constructs, aimed to obtain verisimilitude and applicability in addition to being recognized and acknowledged by informants (Stewart 1998). Throughout the project period, we have on average been in contact with or visited the newsrooms on a monthly basis, and have continuously tested the findings from one organization in the other two newsrooms, to identify what factors are context sensitive and what are common for medium-sized media organizations.

4 Six steps to change: from separation through transition to reincorporation

Through collaborative efforts with the organizations during the first 3 years of the project, a number of co-creative initiatives were made towards implementing new work practices and production flow in the everyday running of their newsrooms. Many of these initiatives never made it out of the workshop setting, while others were introduced for a short period of time (2 weeks to 3 months), before the newsroom went back to working and producing news according to their habitual ‘business as usual’. These repeated failures of implementing changes that would ‘stick’ in the organizations over time, led the research team to start analysing the implementation attempts that had been conducted in the three participating organizations over the past 4 to 5 years. The aim was to identify the factors that prevented initiated changes from becoming permanent, and also at what points of the innovation process these attempts fell through.

Approaching the issue through the lens of Turner’s (1986) theory on liminality, one clear finding was the need to lower the threshold for new changes or innovations—if the threshold either into or out of the liminal phase of change was too high, there was also high probability that the initiative would fail. Inspired by van Gennep’s (1960) division of the rite of passage into the phases of separation (divesture), transition, and incorporation (investiture), we identified the stages that an innovation process in the organizations would have to move through to be successfully, and permanently, implemented. Following this line of thinking, the research group sketched out an analytical framework called “the six step process”, that could hypothetically be applied by researchers and practitioners alike not only to identify how and when an attempted innovation initiative or change process stopped or failed, but also to understand and facilitate for successful change processes in news organizations and beyond.

As the analytical framework was at this point, modelled primarily on failed change processes, its validity as a (practically applicable) model for successful change processes did at this point remain a hypothetical one. In 2017, the model was eventually put to the test, as one of the participating news organizations successfully implemented the flowline production mode as a practice, implicating an enduring change in their everyday work flow.

5 Moss Avis—a successful local initiative

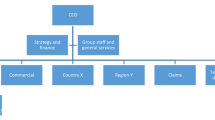

The local news organization Moss Avis employs about 30 persons and is part of the large Norwegian corporate media group Amedia, and has a circulation of about 12.000 copies and 44.000 daily readers. Similarly to many other news organizations, Moss Avis had adopted a ‘digital first’ strategy with the aim of developing a newsroom that integrated and synced the production of both online and print news—“one newsroom, one product”. Prominence was thus given to the digital distribution of news over the printed edition, even though the latter still generated 70% of their revenue. However, as the OMEN research group clearly identified through interviews, informal conversations and participant observation, even though they had published online news for more than a decade, the organization was not practicing digital first, as they were still producing news according to a paper edition deadline logic.

In the spring of 2017, the news editor in Moss Avis turned to the OMEN researchers for advice on how to go about initiating and following up a change process on their own, without external involvement from the researchers. The management group had recently received updated metrics from the Amedia group’s development team, which is responsible for accumulating and distributing advanced metrics and analytics from all the group’s newspapers. All newspapers are measured against each other, and asked to improve their production based on a previously conducted systematic content analysis designed after factors that make stories ‘go well’ online, that is stories that are read by many, and also contributes to more subscribers. According to the latest metrics, Moss Avis was lagging behind both when it came to the number of readers of their digital stories, and the number of stories that the newsroom posted during a full day of work. These numbers were according to the news editor a motivating factor for the management group to decide that something had to be done.

The aim of the change process was, according to the news editor, to explore possibilities for establishing a flowline mode of production in the newsroom. The management group of Moss Avis had embraced the flowline metaphor when it had been introduced by the researchers the previous year, exemplified for instance by how they seamlessly started making use of the term as an integrated part of the conversations and discussions unfolding. In the words of the editor-in-chief: “I do think we are in the core of a way of thinking (…) if we were to achieve something on this together with you, I am sure these are models that will make an impact”. In discussions between the researchers and the management group, a shared notion of what a flowline approach would imply had emerged; a work rhythm of continuous delivery of stories throughout the day, a surplus of stories, increased self-management, better ideation and creative discussions of ideas from start—resulting in making stories ‘fly on the web’. It would be a continuous production cycle, adapted to the needs of ‘others’—the audience and sources rather than the newsroom staff. But how to do flowline in practice remained to be explored and defined.

The researchers’ preparatory discussions with the news editor were largely based on the empirical data from sit-alongs in the newsroom the previous year, as well as the analytical insights on liminality and generative metaphors. Drawing on these inputs, an autonomous working group consisting of four journalists with the mandate and responsibility for planning and organizing the change process was appointed by the news editor. Their work consisted of talking with everyone in the newsroom and preparing concrete and practical suggestions to how and what they could do to change the workflow. The group then invited the whole newsroom including the managers, to a workshop. Here the discussions and suggestions were presented, discussed and agreed upon among all participants. A 4-week test pilot period was then initiated and became a central premise and milestone for their work.

While the researchers did not take part in or facilitate for the practical implementation of flowline in the organization, we still needed to collect data on what unfolded. During the 4-week pilot period one researcher thus spend two days collecting empirical data through observation in the newsroom’s open office landscape, conducting 10 sit-alongs with the editorial staff, and having conversations with the three editors in the management group as well as the journalists in the autonomous working group that was most closely involved in the preparation for and execution of the process of implementing the new changes. The researcher also returned to the organization some months later, and conducted informal conversations with several members of the staff, including the editors. These investigations provided the research team with thick descriptions of the process through which flowline had been established as a new practice and mode of production and workflow in the organization, forming the foundation for a confirmation and adjustment of our model of six stages for enabling change in organizations presented below. The empirical material necessitated a nuancing of the steps within the three phases of transformation originally developed by van Gennep (1960). We defined step 1–3 as belonging to the initial phase of separation where one steps out of the ordinary, step 4–5 to the liminal phase of transition where the change is imagined and realized, and step 6 as the phase of incorporation where one returns to the familiar, but in a changed capacity. A key here, that is the first identified—and most fundamental—step in the separation phase, was to involve everyone in the newsroom in this process of change. This is where the autonomous team became integral.

5.1 Step 1 Involvement: All in!

“I was part of the group that worked on this, it was a good management decision to involve everyone”, one of the journalists in the newsroom stated in an informal conversation a few months after the pilot period. Together with three others, he was in the spring of 2017 invited to join a working group that met multiple times, with the task of coming up with ideas that would lead to an increase in production volume to liberate more time to work on the more challenging news stories. The news editor sat in on the meetings, taking notes and providing background and facts. This culminated in an innovation seminar with all staffers in the newsroom where the working group presented their suggestions for incremental changes in the newsroom production, followed by a general discussion and a show of hands: How many were in? One of the journalists in the working group later explained how “we got to decide ourselves, I think everyone is satisfied about that. It is important that everyone is onboard.”

We define step 1 of the separation phase as follows: Participation and inclusion entail that (1) everyone who may at one point or another be affected by the changes must be given the opportunity to be involved in the process, and if they commit, (2) are responsible for contributing their best efforts to the change process when they step out of the ordinary. This is where a lot of change processes seem to fail, because managers lack a strategy for including everyone in the organization from the very beginning, throughout the preparation, test and adjusting periods. Here, the autonomous team got to decide on the best strategy for involving everyone.

The news editor told us how the preparations that the autonomous working group did before the seminar was crucial to create a feeling of common ownership to the process, and that “when we sat there at the seminar, people probably felt that a lot had already been invested (in the process)”. It was soon established as a common sentiment among the employees about how important it was to get everyone onboard, that it was not acceptable with “free riders” in the newsroom. Inspired by the flowline approach, the working group suggested among other things that the journalists would produce two so-called “quick stories” every day before noon, before they started working on larger news stories. The “quick stories” have only one or two sources, can be solved quickly and are mainly positive news that locals would have an interest in knowing about. They are published online first, not waiting for the paper deadline at the end of the day, like the more traditional format of “notices”. These were defining criteria that the working group decided on and adjusted after a plenary discussion at the staff innovation seminar. According to the editor-in-chief, these “quick stories” have been very important for the paper desk, who now have an abundance of minor stories and notices to work with when designing the newspaper pages. These were stories previously not acknowledged as ‘news’ by the editors. He adds that they are still detailing what a ‘quick story’ actually is, as this is important to get the flowline production mode to work. The teamwork made it possible for everyone in the organization to contribute with suggestions on the practical implementation of these incremental innovations (for example, to decide on the defining elements of a ‘quick story’). We later observed how this was mentioned in the notes from the working group meetings: “All in, or else it will not work”.

They also suggested that all staffers made use of the digital publication tool Escenic® instead of the paper production tool Saxo®. This was not the first time they had tried to implement this change, but this time around it seemed to be crucial that they combined it with a lot of other minor measures, that in sum made it obvious to the journalists why it was important to publish in Escenic®. They agreed that no exceptions for individual journalists or situations would be made, it had to be a unified effort. This also implicated the use of the digital planning tool Trello®, where the news editor exclaimed, “I have sold this to the staff, saying that absolutely everything needs to go into Trello, or else we cannot trust what we see, trust the system anymore.”

As noted by Beech, “[t]ypically, the liminal process is ritualistic, starting with a ‘triggering event’ and is then conducted in specific places for a specific period of time” (2011, p 3). The first criteria for success (‘triggering jolts’) is then related to the level of participation and commitment by the employees taking part in the innovation seminar. The importance of participation and inclusion is twofold. First, it is in our experience of significance that all those who might at some point become affected by the changes made in the work practices that are the topic of the workshop are involved in the process. Second, and equally important, is the issue of employees’ commitment to the process as well as innovation in the news organization itself. According to Turner (1982) the nature of liminality is often of collective and egalitarian character—and there exists a “sense of togetherness among liminals” (Garsten 1999, p 611). The autonomous working group was key to designing action points for this ‘togetherness’ to happen, because they clearly understood the dynamics of the newsroom and what it would take to get everyone aboard.

It was revelatory to us that our empirical material from the pilot period in this local news organization was so in line with what we previously had identified as a crucial factor for lasting change: to involve everyone in the change processes to avoid both ‘free riders’ and the habitual “back to the everyday” practices. We had witnessed several processes in all three organizations stopping very early on because it was management initiated, and the suggested solutions/implementations were based on management perspectives/interests. For the managers to let go of control took a lot of courage, and was enabled by the awareness raised through transformative inquiry with the research team.

5.2 Step 2 Justification: creating awareness

Through ongoing field work in the newsroom it soon emerged how it was particularly one practice the journalists themselves did not know how to change: their inclination to make what they named “the muddling in the middle”-stories (literal translation from Norwegian: “dritten i midten”-saker). These are usually produced by the journalists to ‘fill the newspaper’ pages of the paper edition. The ability to define more clearly what was ‘quick stories’ and what was material for larger news stories thus became crucial to the newsroom staff when transitioning to the digital production of flowline. As one of the journalists with the decidedly best results after the pilot period changes were implemented told us, the introduction of ‘quick stories’ also made it more clear what kind of stories and level of quality were expected by the editors. “There isn’t so high demands of quality as before, on every news story. Before every story had to have many sources and to be worked on rigorously.” This change seemed to bring on a collective change of awareness and a professional logic (Westlund 2017b) on what it is important to prioritize when working with a particular case. The autonomous team decided, and managed to reach common acknowledgement and an actual pledge from the general staff, that they would no longer be ‘saving stories’ for the paper edition, taking away the status attached to such practices.

We define the second step in the separation phase as follows: articulate, sort and categorize issues that are experienced as important to do something about. Identify problems and challenges—often as an interaction between presentation and joint articulation of what the current challenges are when stepping out of the ordinary. Working in steps to include everyone seem to secure ownership to the change process and also to be a source of practical knowledge on where the enablers and barriers for change lies in the organization. Such open action strategies are characterized by delegative leadership and participative action across organizational boundaries (Gebert and Boerner 1999).

One journalist describes it like this: “There is little in this that is about how to solve a story in the best possible manner. We have to accept that everything cannot be equally important.” One of the side effects that the management hoped for when the autonomous working group suggested to implement the ‘quick stories’, was that the journalists would change their daily rhythm of production. Instead of starting the day with a clean slate, they would now prepare for the next day in the afternoon, schedule interviews and adding brief descriptions of the stories they planned to make in Trello®—before they left work. This would hopefully lead to an increase in the number of stories produced by the staff, which in turn would generate more readings, and thus help the management deliver on the expectations from the consortium. This was their interpretation of and concrete implementation of the flowline metaphor.

A major obstacle for initiating change and make change happen is the cognitive frames of organizational members (Pettigrew 1987). Thus, there is a need for creating awareness of why change is needed. A central component of the methods used in OMEN was the focus placed on news workers’ own experiences and perspectives. Being successful in implementing change, we have found that it is in the initiating stages essential to work closely with the workshops participants to make them identify the problems and challenges they experience related to a specific subject or practice. Putting their experience into words through interaction with each other enables a sorting of problematic issues, which helps create ‘order in the chaos’ that characterize the ordinary working day of news employees. Considering how the liminal makes humans take a step back and reflect about their situation (Howard-Grenville et al. 2011, p 525) this stage is clearly one in which the liminal practice of collective reflection is active (Beech 2011), laying the foundation for making autonomous suggestions and decisions.

5.3 Step 3 Motivation: enabling change

«It [Trello] is our universe. The genius thing that we invented, is the colour coding”, the digital editor tells us. Trello is an online planning tool implemented by the newsroom a while back, but the editor explains how the redemptive moment came about, when the journalists in the autonomous working group themselves suggested what colours would symbolize what phase of the production process, adjusted these categories after a discussion with the whole newsroom in the innovation seminar and was integral to further testing on an everyday basis. Red means an idea is’taken’ by a journalist, the colour is changed to yellow when someone is working on the story, green means that the story is written and exported to Escenic®, while pink signals that it is published on the online front page and black indicates that the story will be published in tomorrow’s newspaper. One of the journalists from the autonomous team told us that the previous colour coding, defined by the management group, did not make sense to the newsroom staff and that it was more confusing than clarifying. Now they have in collaboration with the whole newsroom staff, according to this journalist, come up with a “very good tool for following the story from start to finish, we have nailed it when it comes to finding what labels and points in the production process to put markers on”. As the digital editor explains, now everyone can take a quick glimpse of the screen showing the Trello boards, and know exactly how the condition in the newsroom is at any given moment. Previously, this was information reserved for the editorial group, contributing to high stress levels for the individual journalist who felt they had to ‘deliver’ to save the newspaper production that day. The shared visuality of Trello® thus became a way of increasing autonomy and self-management among the newsroom staff in general, through agreed upon, self-defined categories and markers for the news production process and rhythm.

These enablers for change can be small in themselves, but together they are significant (Gibson 1979). The journalists describe how the everyday work life has improved, with the new format of ‘quick stories’, the Trello® colour coding and other tools that give oversight. They now use an Excel® form as a living and shared document that show all the planned stories for both the paper product and the online news page, and the copy editor explains how this relieves him and his desk colleagues of ‘chasing stories’ in the newsroom. The production volume has reached such a high that the newsroom staff are no longer desperate for stories “to fill the paper product with”. “We put it in system, with the ‘quick stories’ and the planning of larger stories. It really does something to you when you no longer have to sit in the morning meeting, making a news story like a straitjacket”, one of the journalists stated.

We define the third step in the separation phase as developing suggestions on how to solve the challenges identified and what can be done differently. Anchoring the need for change in the organization properly will increase the probability for the changes to be permanently embedded in everyday practices. Also, crucial for success seem to be to clearly identify what tasks should be done and by whom, as well as to create and adapt relevant tools that can be used by everyone. To identify the enablers for change in each context, we also see that knowledge about people’s motivation for change is needed.

The news editor explains how the journalists now mentally let go of the story once they have written the piece, in contrast to their previous work mode, where they ‘followed’ their own stories throughout the content management system, all the way to print, which was previously the final legitimization of it ‘being a story’. This outdated way of working was characterized by a lack of trust of the news desk and or/editors handling of their stories. They found that to ‘let go’ of your story is crucial to get the production volume up, which in turn is decisive when it comes to the numbers of readers and potential subscribers of the newspaper. Decisions based on metrics like these are also a type of enabler that potentially have huge influence on the everyday newsroom production (Petre 2015). In a meeting the digital editor asked rhetorically, “when people are reading our online news, do we publicize in sync with this?” She tells us that they have now decided to push stories both earlier and later in the day, when digital readers are most active, and that they have customized an excel form to document changes over time and the production volume of each individual journalist.

Our observations of the three news organizations’ attempts to facilitate for organizational innovation over the years, also made it obvious how these change processes are often initiated without the practical or technological infrastructure in place, and how the lack of knowledge or training in new systems hinder effective change. In introducing the ‘quick stories’, we saw that ideation became separated from the making of a story, and the news staff could work with several stories in parallel. By introducing a backup plan for when a story fell short before deadline, the production cycle now resembled a ‘hurtline’—that is, no one was ‘shot’ anymore. The deadline was dead. The newsroom was moving into flowline mode.

Letting the news workers themselves identify the issues at stake as well as bringing forth potential solutions implies that the suggested changes to a larger extent can become anchored in the organization, which in our experience in turn implies a better chance that these changes become permanently embedded in everyday work practices. Swan et al. argues that “[…] the link between liminality and creative agency is not confined to roles and spaces (consultancy work, professional expertise) that are positioned across organizational boundaries, or free from norms and expectations, but may also apply to roles that are ambiguously situated within organizational contexts and that are subject to divergent expectations” (2015, p 1). Being both a regular member of the staff and a temporary member of a working group with delegative leadership and high team autonomy, creates this ambiguous situatedness. Reflecting collectively about affordances may bring ambiguities ‘out in the open’ and offer new possibilities regarding not only about what can be done, but also who is going to do it.

5.4 Step 4 Actualization: concretizing and testing

The journalists describe how the division of labour has changed with the new flowline regime—back to how they did things when they were 125 employees, instead of the 30 employees they are now. “Now the journalist makes the story, and then it is someone else that manages that material. This is how it used to be, you just pour out content”, the digital editor explains, referring to how the newsroom production flow was before online publishing was introduced. The reduction of individual responsibility and the focus on making content, seems to contribute to a lowering of shoulders for everyone in the newsroom—even the copy editor, who states: “The journalists appreciate it, not to fondle with the quick stories, (or) making headlines”. The new tools designed to help with digital transformation become change agents themselves, contributing in keeping the process of concretizing and testing up to speed (Hargadon and Bechky 2006). “Now we have a lot of stories, now we get everything. We have always something to work on”, the digital editor says.

We define this step in the liminal phase as translation of suggestions to specific solutions, tools, models and practices aligned to everyday life. The new constructs are named (for instance ‘quick stories’ or ‘flowline’) and preparations are made for how they can be utilized or put into practice. This step represents a transition from a controlled innovation process, often with support from outsiders (experts such as the research group), to an ambiguous state where the employees collectively (in autonomous teams facilitating for the whole newsroom) are given the responsibility for bringing the process forward, reducing the need for micro-management and make delegative leadership possible. To give room for adjusting what did not work and breathing space for managers, we thus recommended the management to define the initial change process as a pilot period. This enabled the employees to gain ownership to the change process and its progress, and relieved the need for micro-management. Changes in organizations are often kept, not out of need or success, but out of managers’ fear of admitting failure. A testing period we thought would give courage and flexibility to the whole newsroom. In our experience, it is paramount that one collectively agrees on the length on the test period and communicate this as a “before and after”, while also having the tools for measuring what happen throughout the period.

“What is genius about this for us in the editorial group, is that I can now scroll through […] really quick, now my gaze is like: when something is green, not black or pink I stop, that is the storage”, the digital editor explains. Their work day is easier to manage, also because they now are more prepared in the morning. The editors do a quick clean-up of the Trello boards each evening, sorting what the journalists have filled in, and colour code the stories that are already published. “You can be certain that you haven’t overlooked something that has been a problem, arms and legs, desk, journalists, photographers, editors. Enough that people are annoyed”, the news editor explains. In discussions with the editorial management group, this surfaces as one of their deliberate goals with the new flowline regime; to enable the editors to be better prepared. This resonated with the autonomous team’s priorities for improving the general work flow in the newsroom.

A requirement for success in a change process seems to be that the news workers’ suggestions for change are developed into specific tools, models and practices that can be put to use in the organization. Part of this is to give the developed tool or model a specific name, and to make a (semi-)official decision to start putting it to use. This stage is significant in terms of how it represents the transition made from the innovation process being guided and forwarded by external change makers (i.e. the researchers arranging workshops) to the organization’s own participants taking on the responsibility to bring the innovation process forward, as a form of indigenous change makers. The materialization of ideas for change into actual tools and models that can be put to use, implies that these new tools do themselves become agents of change contributing to keeping the innovation process rolling. One of the mechanisms to engage liminality is relating new and existing organizational resources (Howard-Grenville et al. 2011) through the liminal practice of recognition (Beech 2011).

«Before we had to help the desk filling the pages, now the desk has to clear space for us”, one of the journalists tells us. One of the unintentional effects of this change process was that this ‘digital first’ practice (Singer 2018) made the paper production be part of the flowline regime. Hence, the successful digital transformation turned into an unexpected integration of the paper with the digital production flow. “Now we start every morning and have finished stories to use in the newspaper ready, there is a much larger degree of preproduction”, the copy editor explains. “We are planning the content, not tomorrows newspaper”, he adds. This makes the work day more predictable. The newsroom’s ability to implement and use new tools, follow up new work routines and test new technologies (Raviola and Nordbäck 2013) without outside support from a technological development team, seem to be decisive here—and the implication of how the changes spur consequences that are visible in daily work life, is not to be underestimated, according to the news editor: “This is our capital [what we assign to Trello], we cannot slack down on this. The journalists totally agree, they think it is really good, they see that it works».

The rules they have agreed on have to be held high by the collective, the news editor describes: “If you have an idea that you are unsure of will ever become a story, don’t assign it. There is a threshold for when this is an idea.” If the changes actually work out, the newsroom staff have to trust that what they see visualized in Trello, is real. The digital editor explains how the excel forms they have implemented also helps relieve the work load, as they delete the content immediately after the stories are published. “Out of sight means published, it gives a feeling of cleaning up and throwing away”, she states. In this way, we see how the employees take measures to secure the implementation of changes. If the news workers do not make efforts to start using the tools they have themselves developed, these tools stand little chance of making it into the everyday work practices of news production. We see here how liminal roles are enacted (Swan et al. 2015) and how the mechanism to engage liminality in this stage is experiencing the new through ‘doing’ (Howard-Grenville et al. 2011).

5.5 Step 5 Appropriating: taking the new/changed practice for granted

The copy editor describes it as a mental change: “We can sense it with the journalists”, he says, and describes how this group of workers no longer seem to be preoccupied with getting the midsection in the paper product for their story, but rather are focussed on producing content. One of the first signs of lasting change, is when the new suddenly becomes taken for granted (van Gennep 2004/1977). «Now the journalists don’t think that much about whether a page is open, there aren’t that many open pages [in the print edition]. They write a story, count on it being put into print in a day or two”, the news editor states. He describes how the newsroom in a short time span have ventured from everyone being involved in the production of the paper product with individual autonomy and worry about whether they had ‘enough stories’, and competing about the front page, to most staffers no longer thinking about it. It has become a collective effort to produce stories, regardless of the format of publication.

We define the final step in the liminal phase as follows: New tools and practices are embedded in the organization and the employees’ ways of working. Modifications and adjustments are still being made, but the original main ideas remain. Perception of the change shifts from being something new and unusual, to being taken for granted and integrated in everyday life.

When visiting the newsroom a few months after the pilot period, the journalists told us that a lot of the rules that the working group suggested, and that the staff decided on in the all hands seminar, were now dissolved—as they were not needed anymore: “It is not quite like we are delivering two stories by noon, it was like that the first few days, I had totally forgot this, now it seems like they do the quick stories when they have time for it”, the news editor explains. According to the digital editor the journalists now write a quick story when they perceive that it is important to get it out there—and sometimes it becomes a larger story than what they originally thought. The time spent on writing notices is heavily reduced, precisely because they are not writing after a word count. They write what is needed, before they file the story in Escenic®. Then someone else takes over.

The stage of appropriation is the process through which newly developed tools and practices start becoming embedded in the organization, in people’s practices or ‘ways of doing things’. As it is adjusted to the overall news production practices, the tool or model might be modified, simplified, or adjusted, with the main idea still remaining. This is thus the stage through which the developed tool goes from being something new and unfamiliar towards becoming embedded into the everyday and 'taken-for-granted'. It is also where the autonomous team is dissolved. Here, the liminal practice of experimentation among all employees is active (Beech 2011), as “providing opportunities for participants to experience the new, helps to move the new cultural resources (ideas, approaches, etc.) from the realm of the possible to the doable and practical” (Howard-Grenville et al. 2011, p 532).

5.6 Step 6 Adaptation: reinforce and secure change

During the 4-week period in the fall of 2017, the volume of the journalists’ published stories increased with 40% and the number of readers on their online site increased with 30%. For some of the journalists the increase was formidable. An experienced journalist with the responsibility of covering the city hall (something usually deemed to be not so reader friendly or catchy), got an increase in readers of 135%—and a spontaneous applause by her co-workers when this was communicated during a newsroom meeting. She told us that the new system suits her personality a lot, she likes having oversight, predictability and flexibility: «I file my own stories when they have gotten all the colours [in Trello]. The management has told me they want to do it, but I do it myself”, she explains and adds how this makes it easier for her to find them again if needed.

We define the reincorporation step as follows: Once the change is integrated into the organization's practices, it is easy to forget how it came about. By reminding oneself that this was the result of a development process, one can be inspired to make new changes and lead to initiation of a new step 1: "All in!". Note that the metaphorical work is essential here, because the change is now embodied as a new, common discourse. It is easy to slip back into old routines, also without intention. We see how maintenance strategies are necessary, especially if these are designed to fit the individual or collective needs and motivation of both employees and managers. This is a phase where closed action strategies become important, to secure knowledge integration among the staff and managers. Celebrating success regularly and having ways of providing updated ‘proof’ of why the change process was a good thing to go through, also seem to help when the organization takes on their next challenge.

The journalist with the largest increase in readers also showed a strong motivation for being read online, and were regularly leaning over the front desk to check the numbers of readers on her current story. At the same time, several of the newsroom staffers had thoughts about whether this will continue to be a lasting change—or just another attempt that eventually would fail. “The feeling that this is something that it is important to spend time on can soon disappear if one doesn’t get the confirmation that this is the mission”, the news editor points out. The management had some strategies put in place already, to avoid the newsroom from falling back into old ways. One of these is that the news editor has regular conversations with each journalist, where they discuss the individual production volume and readership. This directive leadership strategy contributes to a differentiating of responsibility, but can also be said to involve disciplining and surveillance of the individual employee, something that used to be based on gut feelings and rough estimates, not precise metrics (Petre 2015). The first weeks after the change process was piloted, the results were presented in detail for the whole newsroom on a regular basis. This contributed in “keeping the speed” also after the success was a fact, the news editor argues. “I need to have a strategy for follow up until this sits in the spinal cord (of the newsroom). This is still fresh, and will not continue like this by itself”, he responds when we ask him how he views the near future.

The final stage in the six step change process occurs when the change in question has become properly integrated into indigenous organizational practices. One indication that this has happened is that the news workers no longer refer to the flowline mode, indicated through statements such as “we don’t really use that method anymore, we just do it anyway”. Another indication that innovative metaphors like flowline has been adapted into the organization is that the staff have 'forgotten' how it originated, and conceive of it and present it as something they have come up with themselves and ‘just started doing’. While this downplays the role of the exogenous change makers like action researchers or technological development teams, it points towards a successful implementation, as the indigenous change makers clearly find a sense of ownership in the change made. Like the editor-in-chief of the national daily newspaper also part of the OMEN project explained it, when they implemented flowline in a six step process a year later, “this is magic through many minor measures”.

How is the change process experienced by the employees themselves? One of the journalists, who also was part of the autonomous working group, describes the situation a few months later in this way: “The work environment is improved, there is less stress and increased production”. Before “we tried to invent the newspaper in the morning”, the editor-in-chief explains. When the news editor in a conversation describes the success of the newsroom, he says «I think it was all about us taking a real charge, more clearly than in earlier circumstances». The needs of the paper product are no longer governing their editorial prioritizations, so much that we may call it’digital first’ or flowline.

6 Conclusion

We have in this article explored the use of theories of liminality and generative metaphor to explain the change in temporal structuring of work practices in a news organization through the actions of a temporary autonomous team—from deadline to flowline in a series of liminal steps. News organizations and their employees currently find themselves somewhat ‘jetlagged’ from being tossed into a stage of uncertainty and insecurity, having to operate in what might be described as a constant betwixt-and-between phase characterized by ambiguity. The level of insecurity, and thus anxiety, that news workers experience, remains at a steadily high level due to how they repeatedly, albeit irregularly, are subjected to short notice announcements of cost cuts, downsizings and centrally managed re-organizations. Radical changes and the experience of being tossed into unwanted liminal phases is thus something that news workers have to relate to, and attempt to cope with, with irregular intervals. While aware of the fact that their established work practices do not make them particularly well-equipped to manoeuvre in this ambivalent landscape, and that they need to re-innovate themselves to be able to survive as news workers as well as news organizations, they largely continue to do things the way that they ‘always’ have. This might be related to how the news workers’ established knowledge and competence represents something stable for the individual surrounded by uncertainty, and the thought of having to ‘venture into the unknown’ when it comes to news production practices increases the experience of stress, insecurity and ambiguity.

To create change, and not at least lasting change, under such environmental conditions, we highlight the performative qualities of metaphors as enablers for transformative change and suggest that generative metaphors have the potential to actualize and spur sequences of change by creating new temporal structures (flowline) and possibilities for action not previously imagined. By provoking, connecting and brokering different views in the newsroom and allocate decision-making and ownership to employees in the form of temporary autonomous teams for spurring change, our findings suggest that such teams address work from the perspectives of the news workers themselves, making them the main source of ideas for and implementation of innovation and processes of change. This is particularly important in domains where the need for digital transformation is urgent, yet where the structures allowing for autonomous teams to contribute substantially to that change are traditionally absent. We find that if the threshold to enter a new action domain and the liminal phase that characterizes it, or the threshold to bring imagined change out of liminal space and back into the indicative mood of everyday work life, is too high, the chances increase that one might stumble on the threshold. We also recognize the strategic significance liminality has for the implementation of change and innovation in news organizations, while simultaneously emphasizing the necessity of keeping the threshold low when entering and exiting liminal space. Our findings suggest that a fluid autonomous team approach allowed employees more authority in designing their everyday work activities and also facilitated for the team’s learning process to be integrated in the learning of the organization, including the management. Lowering the threshold for innovation increases the success rate for the implementation of change in news organizations, and the magic of achieving lasting change in an ongoing digital transformation seems thus to appear through the many minor steps conducted by collectives that know the pressing issues from first-hand embodied experience.

Notes

The metrics are now designed to count only articles that have been viewed more than 10 s by the reader.

References

Beech N (2011) Liminality and the practices of identity reconstruction. Hum Relat 64(2):285–302

Bygdås A, Clegg S, Hagen AL (2019) Media management and digital transformation. Routledge, New York

Cameron K, Dutton J, Quinn RE (eds) (2003) Positive organizational scholarship: foundations of a new discipline. Berrett-Koehler Publishers, San Francisco

Christin, A. (2014) Clicks or Pulitzer?: Web journalists and their work in the United States and France. Dissertation, Paris, EHESS

Czarniawska B, Mazza C (2003) Consulting as a liminal space. Hum Relat 56(3):267–290

Feldman MS, Orlikowski WJ (2011) Theorizing practice and practicing theory. Organ Sci 22(5):1240–1253

Garsten C (1999) Betwixt and between: temporary employees as liminal subjects in flexible organizations. Organ Stud 20(4):601–617

Gebert D, Boerner S (1999) The open and the closed corporation as conflicting forms of organization. J ApplBehavSci 35:341–359

Gibson JJ (1979) The theory of affordances: the ecological approach to visual perception. Houghton Mifflin, Boston

Greenwood R, Hinings CR (2006) Radical Organizational Change. In: Clegg SR, Hardy C, Lawrence TB, Nord WR (eds) The sage handbook of organization studies, 2nd edn. Sage, London, pp 814–842

Hagen AL, Brattbakk I, Andersen B, Dahlgren K, Ascher B, Kolle E (2016) Ung ogute: Enstudieavungdomogungevoksnesbrukavuterom (Rapport 6/2016). Arbeidsforskningsinstituttet, Oslo

Hargadon AB, Bechky BA (2006) When collections of creatives become creative collectives: a field study of problem solving at work. Organ Sci 4:484–500. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1060.0200

Heron J, Reason P (2006) The practice of co-operative inquiry: research ‘with’ rather than ‘on’ people. In: Reason P, Bradbury H (eds) Handbook of action research. Sage Publications, London, pp 144–154

Hoegl M, Parboteeah P (2006) Autonomy and teamwork in innovative projects human resource management: published in cooperation with the school of business administration. UnivMich Alliance Soc Hum ResourManag 45:67–79

Holgersson H (2014) Challenging the hegemonic gaze on foot: walk-alongs as a useful method in gentrification research. In: Shortell T, Brown E (eds) Walking the European City. Quotidian Mobility and Urban Ethnography. Ashgate, Farnham, pp 207–224

Howard-Grenville J, Golden-Bibble K, Irwin J, Mao J (2011) Liminality as cultural process for cultural change. Organ Sci 22(2):522–539

Lakoff G, Johnson M (2008) Metaphors we live by. University of Chicago press, Chicago

Levina N, Orlikowski WJ (2009) Understanding shifting power relations within and across fields of practice: a critical genre analysis. Acad Manag J 52(4):672–703

Ludema JD, Cooperrider DL, Barrett FJ (2006) Appreciative inquiry: the power of the unconditional positive question. In: Reason P, Bradbury H (eds) Handbook of action research. Sage Publications, London, pp 155–165

Morgan G (1997) Images of organization. Sage , Thousand Oaks

Petre C (2015) The traffic factories: metrics at chartbeat, Gawker Media, and the New York Times. White Paper, Tow Center for Digital Journalism, New York

Pettigrew AM (1990) Longitudinal field research on change: theory and practice. Organ Sci 1(3):267–292

Pettigrew AM (1987) Context and action in transformation of the firm. J Manage Stud 24(6):649–670

Raviola E, Norbäck M (2013) Bringing technology and meaning into institutional work: making news at an Italian business newspaper. Organ Stud 34(8):1171–1194

Reason P, Bradbury H (2006) Handbook of action research: the concise paperback. Sage, London

Ryfe DM (2012) Can journalism survive? An inside look at American newsrooms. Polity Press, Cambridge

Schön DA (1993) Problems, Generative Metaphor − a perspective on problem-setting in social policy. In: Ortony A (ed) Metaphor and thought. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 137–163; https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139173865.011

Singer JB (2018) Entrepreneurial journalism. In: Vos TP (ed) Journalism handbook of communications science.19. De Gruyter Mouton, Boston, pp 255–372. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781501500084-018

Srivastva S, Barrett FJ (1988) The transforming nature of metaphors in group development: a study in group theory. Hum Relat 41(1):31–63. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872678804100103

Stewart A (1998) The ethnographer’s method. Qualitative research methods. Sage Publications, California

Sturdy A, Schwarz M, Spicer A (2006) Guess who’s coming to dinner? Structures and uses of liminality in strategic management consultancy. Human Relations 59(7):929–960

Suchman LA (2007) Human-machine reconfigurations: plans and situated actions, 2nd edn. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Swan J, Scarbrough H, Ziebro M (2015) Liminal roles as a source of creative agency in management: The case of knowledge-sharing communities. Human Relations. 69:1–31

Swidler A (1986) Culture in action: symbols and strategies. Am Soc Rev 51(2):273–286

Tempest S, Starkey K (2004) The effects of liminality on individual and organizational learning. Organ Stud 25(4):507–527

Turner V (1982) From ritual to theatre: the human seriousness of play. PAJ Press, New York

Turner V (1986) Dewey, dilthey, and drama: an essay in the anthropology of experience. In: Turner V, Bruner EM (eds) The anthropology of experience. University of Illinois Press, Chicago

van Gennep A (1960) Rites of passage. Routledge, London

Van Gennep A (2004) The rites of passage. Routledge, New York

Wagner EL, Newell S, Kay W (2012) Enterprise system projects: the role of liminal space in enterprise system. J Inf Technol. 27:1–11

Watson CW (1999) Being there: fieldwork in anthropology. Pluto Press, London

Westlund O (2017) Interna förhandlingar om journalistikens framtid. Norsk Medietidsskrift 24(3):1–8. https://doi.org/10.18261/issn.0805-9535-2017-03-05

Yin RK (2003) Case study research: design and methods. Sage, Thousand Oaks

Acknowledgements