Abstract

F. H. Bradley’s relation regress poses a difficult problem for metaphysics of relations. In this paper, we reconstruct this regress argument systematically and make its presuppositions explicit in order to see where the possibility of its solution or resolution lies. We show that it cannot be answered by claiming that it is not vicious. Neither is one of the most promising resolutions, the relata-specific answer adequate in its present form. It attempts to explain adherence (relating), which is a crucial component of the explanandum of Bradley’s relation regress, in terms of specific adherence of a relational trope to its relata. Nevertheless, since we do not know the consequences and constituents of a trope adhering to its specific relata, it remains unclear what specific adherence is. It is left as a constitutively inexplicable primitive. The relata-specific answer only asserts against Bradley. This negative conclusion highlights the need for a metaphysical account of the constitution of the holding of adherence.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

F. H. Bradley’s relation regress, generally known as “Bradley’s regress”, aims to show that the postulation of relations leads to an infinite constitutive regress. According to Bradley’s regress argument, any relation’s relating its relata must consist of an infinite regress of additional relations holding between relations and their relata. Since Bradley’s regress does not terminate, relation’s relating and unifying distinct entities are claimed to be metaphysically inexplicable.

The relata-specific answer, which is one of the most promising current attempts to deal with Bradley’s regress (Betti 2015; Maurin 2010, 2011; Wieland and Betti 2008), introduces relata-specific relational tropes. Such tropes are entities like particular 2-m distances primitively relating their specific relata. They are assumed to avoid Bradley’s regress because the existence of a relational trope r entails that r relates certain specific relata a and b: it adheres to (“relationally inheres in”) them and to only them in every possible world where r exists. For instance, the existence of a 2-m distance trope entails that certain specific entities a and b are in 2-m distance from each other.

In this article, we argue that in spite of being an interesting general approach, the relata-specific answer in its present form is inadequate. The main reason for this is that the relata-specific answer introduces particular relations which adhere to their specific relata but leave the consequences and constituents of this specific relating, or, what we prefer to call “specific adherence”, unaccounted for. As a consequence, we do not know of what the relating of a relational trope of its relata consists: what it is. A successful answer to Bradley’s regress should spell this out in more precise terms and go beyond the slogan that relations relate their relata. A crucial worry here is the determination of the spatio-temporal location of the the relational trope in relation to its relata.

After presenting a novel constitutive reconstruction of Bradley’s regress argument in Sect. 2, Sect. 3 provides a detailed presentation of relata-specific answer. Finally, in Sect. 4, we argue that in its current form, the relata-specific answer is inadequate.

2 Bradley’s Relation Regress

F.H. Bradley’s relation regress occurs in the fourthFootnote 1 part of his argument in Book 1, Chapter III (Relation and Quality) in Appearance and Reality (1893): relations with qualities or relata are “unintelligible” (AR, III, 27–8).Footnote 2 The systematic problem that the regress argument poses is why an entity relates and unifies distinct entities (cf. Perovic 2017, sec. 1.2). Accordingly, the argument begins by supposing that an entity, let us call it “r”, relates two distinct entities “a” and “b” and asks initially why it does (Wieland and Betti 2008, 512; Maurin 2010, 314; Betti 2015, 56).Footnote 3 Relating means that r is an entity of a determinate kind R and r adheres to (“relationally inheres in”) a and b.Footnote 4R is not some definite entity but any relating entity whatsoever; the starting point is general.

To take a simple example as an illustration, let objects a and b be in 2-m distance from each other. Entity r is the relation of the distance of 2 m, which adheres to a and b. So relating consists of two components: (i) r is an entity of a determinate kind R (2-m distance) and (ii) the fact that r adheres to a and b (a and b are in 2-m distance from each other in plain English).

The second assumption in Bradley’s regress is that relation r unifies a, b and itself into a complex individual, relational complex arb (cf. below; Wieland and Betti 2008, 509–11; Maurin 2010, 321; Betti 2015, 39–41).Footnote 5 There is a complex relational individual of a and b being in 2-m distance, for instance. This assumption is distinguished from the relating assumption in the contemporary literature, as is documented by Perovic (2017, secs. 1.2 and 2.2). One may defend it by pointing out that if r relates distinct entities a and b, then all these three entities should form, in one way or another, a single complex entity of some ontological category.

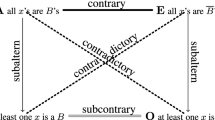

The next step in the regress argument is Bradley’s crucial assumption, which triggers the regress. Let us call it accordingly Bradley’s trigger: if relation r relates a and b and unifies them and itself, it itself must also be related to and unified with both of a and b. For example, the relation of 2-m distance is itself related to and unified with both a and b. Hence, the only way for r to relate and unify a and b is being related to and unified with both a and b. On the assumptions of the argument, relation r can be related to its relata only in virtue of two additional relating and unifying entities: entities that are numerically distinct from r and its relata. Thus, there is a new relation r1 that relates r to a and unifies r, a and itself and a new relation r2 that relates r to b and unifies r, b and itself.For instance, if the relation of 2-m distance is itself spatiotemporally located, it needs to bear a relation of distance (or, some spatiotemporal relation at least) to both a and b. From this, an infinite regress of relations is generated by returning to the beginning in the case of r1 or r2. So the regress has actually the structure of a tree with infinitely many levelsFootnote 6:

Accordingly, Bradley’s relation regress may be presented as a series of propositions:

-

1.

Suppose that entity r relates and unifies distinct entities a and b. (n = 0, cf. levels above.)

-

2.

Necessarily, if xn relates y and z and unifies them and itself, then xn is related and united to y by means of a distinct entity xn+1 and xn is related and united to z by means of a distinct entity xn+2.

-

3.

Thus, there is a distinct entity r1 that that relates r to a and unifies r, a and itself and a distinct entity r2 that relates r to b and unifies r, b and itself. (from 1 and 2, two new tokens of the same type as 1)

-

4.

Thus, there is a distinct entity r3 that relates r1 to a and unifies them and itself and a distinct entity r4 that relates r1 to r and unifies them and itself and so on. (from 2 and 3, 4 of the same type as 3)

-

5.

And so on and so forth infinitely.Footnote 7

When we consider Bradley’s relation regress from a present-day systematic point of view, we may say that it begins by seeking for a metaphysical explanation for the fact of a general nature that (i) r is an entity of a determinate kind R, (ii) r adheres to a and b and (iii) r unifies a, b and itself. The problem that the regress poses is to give a metaphysical explanans for this explanandum. As Wieland and Betti (2008, 512) put it: “in virtue of what” does r relate a and b?” In particular, why does r adhere to a and b? We shall mainly focus on the latter explanatory request since we argue in Sect. 4 that adherence is the problem for the relata-specific answer.

Intuitively, this is not a task of causal explanation in which one would be interested in the question what brought about the change in the world that adherence (“AD (r, (a, b))”) holds—that a and b are in 2-m distance, for instance (cf. Dasgupta 2017, 75–6). Rather, here we are speaking about a constitutive problem when considered from the present-day systematic point of view: what constitutes the holding of adherence from r to a and b (ibid.)? What constitutes the adherence of, say, the 2-m distance to a and b? We think that resting on this intuitive distinction between causal and constitutive explanations, familiar from the literature on grounding, is sufficient for the present purposes (cf. Bliss and Trogdon 2016, sec. 4). In this paper, we also would like to stay neutral on different accounts of constitution such as varying views on grounding so that the setting of Bradley’s relation regress problem does not presuppose any specific account of constitution.

A vital consequence of this is that the constitutive problem of Bradley relation regress differs from the modal problem of introducing an entity r of such a type that its existence entails that r relates a and b (cf. MacBride 2011, 167–8 and below). The constitutive problem here goes in a different direction than this entailment as it is asked of what relation’s relating its relata consists. Moreover, any solution to the modal problem presupposes that the constitutive problem is already solved: if relating is entailed by the existence of some entity, we should already be able to specify what that relating is. If we take Bradley’s regress argument seriously, we cannot take it for granted that there is any metaphysically unanalyzed (“primitive”) relating because this very assumption might be conductive to an infinite regress.

Furthermore, we adopt the categorial conception of metaphysical explanation: one postulates an ontological category or categories of entities as an explanans for the explanandum, which is also put in categorial terms. The perdurantist line of explanation of persistence, to use another illustration, may be seen as categorial since the perdurantists postulate the category of temporal parts to account for the persistence of objects as perdurants (another alleged ontological category). The categorial conception may be called “formal ontological” since forms of being (e.g. being a part) are involved in the division of entities into ontological categories (Lowe 2006; Simons 2010, 2012; cf. also Smith 1978, 1981; Smith and Mulligan 1983). In our specific case, one has to provide a metaphysical explanation for (i)–(iii) above. With regard to (ii) r adhering to a and b (“AD r, (a, b)”), the task of metaphysical explanation is to provide an answer, in terms of one’s preferred category system, to the question what constitutes the holding of AD (r, (a, b))?Footnote 8 An answer to this question is needed in order to spell out what it is to be a relating entity, that is an entity of the category of relations.

The conclusion of the regress argument is that trying to find the explanans leads to a vicious infinite regress. Recall that r is any relating and unifying entity whatsoever. Therefore, the vicious infinite regress has the global consequence that there can be no metaphysical explanation for the fact that an entity relates and unifies distinct entities. The regress is vicious for two main reasons. First, any relation’s adhering to its relata a and b is metaphysically explained by means of the holding of an infinite number of relations, but there is no bottom-level, in which the regress would be terminated. Second, relation r’s adhering to a and b is accounted for by introducing new relations, but nothing at all is explained about the global metaphysical problem of an arbitrary entity r’s adhering to and unifying distinct entities. This general problem of the same type is just repeated infinitely without a termination (cf. Bliss 2013). Relating and unifying distinct entities in general remains metaphysically inexplicable.

3 Relata-Specific Answer to Bradley’s Relation Regress

The standard contemporary solutions and resolutions of Bradley’s relation regress may be divided into three main categories: factualist, infinitist and trope-nominalist (cf. Betti 2015, 104).Footnote 9 We will not discuss infinitism here because we accept the viciousness of Bradley’s relation regress contra infinitism for the above-given reasons (cf. also Betti 2015, Chs. 2.2, 2.3, 3.1; Maurin 2015).Footnote 10 In the factualist answer, relations are assumed to be two- or many-place universals directly exemplified by two or more objects. The holding of relation R of two objects a and b amounts to the existence of an additional entity, fact Rab. Factualists claim to avoid Bradley’s regress because facts are assumed to be sui generis entities accounting for the exemplifcations of relation universals by objects.Footnote 11 We will not discuss factualism here because Betti, Maurin and others have already presented sharp criticism against it.Footnote 12

The trope nominalist answer introduces entities of the category of relational tropes: particular relations adhering to distinct entities (e.g. instances of spatio-temporal relations). A version of the trope-nominalist resolution is the relata-specific answer suggested by Maurin (2010, 2011), Wieland and Betti (2008) and Betti (2015).Footnote 13 Although differing in some details like being committed to tropes (Maurin) or only hypothetically so (Wieland & Betti, Betti), they agree on the elements that are most relevant in answering to Bradley’s relation regress specifically.Footnote 14 Furthermore, next we will rationally reconstruct the formal ontological variant of the relata-specific answer to the regress on the basis of Maurin’s, Wieland’s and Betti’s publications although they do not explicitly operate within the formal ontological framework. The reconstruction is rational because it is a meticulous elaboration on Maurin’s, Wieland and Betti’s proposals that follows principles of a theoretical framework. We need this rational reconstruction in order to critically evaluate the relata-specific answer to the constitutive Bradley’s relation regress in exact formal ontological terms. In what follows, we will speak about this rationally reconstructed position as “the relata-specific answer”.

The relata-specific answer rejects Bradley’s trigger about the ontological need for new relating and unifying entities by assuming that r is relata-specific: necessarily, if trope r exists, r relates its specific relata in a certain way and unifies them into a certain kind of single complex individual (e.g. a complex of two objects in a 2-m distance). In order to do its relating work, r needs not be related to and unified with its relata by means of distinct entities. Wieland and Betti (2008, 518) characterize relata-specifity as follows: “if R is relata-specific, it relates a and b as soon as it exists, and, consequently, R could not have existed and failed to relate a and b”. Maurin’s way of putting the same point is the following: “relations must be such that they relate some particular relata” (2011, 76). So necessarily, if r is relata-specific, then it adheres to nothing but a and b: it is not possible that r adheres to any other entities than a and b. Necessarily, the relation of “specific adherence” holds from r to a and b (ADs (r, (a, b))).

Specific adherence entails strong multiple rigid dependence (“MRD”, for short) of a relational trope on its relata. Multiple rigid dependence is a three-place (potentially multi-place or multi-grade) formal ontological relation since its holding determines the form of being of its relata as an existentially dependent entity or a dependee (Keinänen 2022). MRD has a form of modal existential dependence (Tahko and Lowe 2020). MRD (r, (a, b)) is roughly characterized as follows: necessarily, if r exists, then a and b exist (for the definition, cf. Keinänen 2022).Footnote 15 According to a plausible assumption, necessarily, if a relation relates some entities a and b, then a and b exist. Since a relata-specific trope must relate certain specific entities if it exists, the trope is also (strongly) multiply rigidly dependent on these entities.Footnote 16 As Maurin puts it: “if the relation exists so must the relata which it then relates […] the relation depends for its existence on the existence of the relata” (2011, 74; cf. 2002, 164; 2010, 323).Footnote 17

The relata-specific answer is supposed to block Bradley’s relation regress by denying Bradley’s trigger. Relata-specific relational tropes are assumed to relate their relata without the help of additional relating and unifying entities. Here, the central claim is that necessarily, if a relational trope r exists, r adheres to certain specific relata a and b. Thus, specific adherence ADs (r, (a, b)) is considered to be an internal relation between relational trope r and its relata a and b: necessarily, if r, a and b exist, ADs (r, (a, b)) holds. The holding of specific adherence also determines the ontological category of r, namely, that r is a relata-specific relational trope. Formal ontological relations determine category membership since they determine the form of being of their relata (Lowe 2006, ch. 3.2; Simons 2012; Hakkarainen and Keinänen 2017; Hakkarainen 2018). Hence, the relata-specific answer presupposes that specific adherence is a formal ontological relation between a relational trope and its relata.

The decisive, but often neglected difference between particular properties (or, modes) and tropes is the following. Particular properties and objects are assumed to stand in the fundamental formal ontological relation of inherence that is metaphysically unanalysable and its holding is explanatorily primitive. There is no answer to the question what constitutes the holding of inherence. The inherence of tropes in objects, by contrast, is metaphysically analyzed in terms of other relations such as parthood, co-location and/or existential dependencies (Keinänen 2022). The holding of these latter relations is assumed to constitute the holding of inherence. For instance, according to the prototypical trope theorist D.C. Williams (1953), trope t is a property of object i if and only if t is a part of i and spatio-temporally co-located (i.e. concurrent) with i. Fundamentally, tropes are particular natures (like particular -e charge in some location) and certain kinds of parts of objects (Hakkarainen and Keinänen 2017; Hakkarainen 2018).

Relata-specific relational tropes compare with primitively characterizing modes assumed by E.J. Lowe (2006, 2009) and John Heil (2012).Footnote 18 Like relata-specific relational tropes, modes are bearer-specific (properties of certain specific objects), and the relation between objects and modes/relational tropes is not metaphysically analyzed further. It does not have a constitution. While modes (such as the redness of a rose) are particular properties of objects, relata-specific relational tropes are particular relations primitively adhering to two or more specific objects (particular ways certain specific objects are related—such as a 2-m distance between two objects).

Lowe (2006, ch. 6.3) considers it to be a part of the non-modal essence of a mode that it inheres in a certain specific object—it is a part of the essence of a certain redness that it is the redness of some definite rose and not a mode possessed by a distinct object. When they define relata-specifity, Wieland and Betti say that it is in relational trope r’s “nature” to relate specifically a and b (2008, 518). However, unlike Lowe, Wieland and Betti put this nature or essence in modal terms: “The point is that if a relation is relata-specific, it necessarily relates its relata, but only if it exists” (2008, 519; cf. Betti 2015, 91). Maurin follows this lead: “If they exists, they must relate what they in fact relate” (2010, 322).Footnote 19 Hence, it is assumed to be a primitive modal fact about relational tropes that they relate certain specific relata. To put this in formal ontological terms, the relata-specific answer considers the specific adherence of relational tropes to its specific relata a fundamental formal ontological relation that is not constituted by the holding of any other relation.

As we noted above, another formal ontological relation, strong multiple rigid dependence holds between a relata-specific relational trope and its relata. Although specific adherence entails strong multiple rigid depedence, the converse does not hold. Strong multiple rigid dependence sets only minimal constraints on its relata: necessarily, if a dependent entity t exists (somewhere, somewhen), then its dependees a and b also exist (somewhere, somewhen). Strong multiple rigid dependence may hold between various different kinds of entities in addition to relational tropes and their relata: for instance, events and the specific objects involved in these events or borders and the objects confined by these borders. In order to maintain that an entity is a relational trope in the more general ontological category of strongly multiply rigidly dependent particulars, one has to add that an entity stands in the relation of specific adherence to its relata—in other words, one has to add that the entity is a relation relating its specific relata.Footnote 20 Simons’ (2003, 2010) “relational tropes” are multiply rigidly dependent particulars, but he fails to meet the challenge of specifying the additional chacteristics of relational tropes.Footnote 21

Finally, a relational trope unifies itself and its relata into a relational complex arb. Necessarily, if relational trope r exists, the existence and identity conditions of the relational complex arb are satisfied: the parts of arb exist due to the holding of MRD (r, (a, b)). Moreover, ADs (r, (a, b)) holds and r also explains the nature of arb as arb and not some different relational complex.Footnote 22 Therefore, r is the entity unifying a, b and itself into the relational complex arb (cf. Betti 2015, 101–2). All this seem to be possible without additional unifiers r1 and r2; r can unify without additional unifiers.

To sum up, the relata-specific answer is supposed to halt Bradley’s relation regress by denying that we need additional relations r1 and r2 to relate trope r to its relata a and b. First, r itself is the required entity of the determinate kind R. Necessarily, if r exists, ADs (r, (a, b)) holds and the trope relates its specific relata in a certain way. Similarly, a relational trope unifies itself and its relata into a certain kind of relational complex. The regress does not proceed to another pass in which relating is reified.

4 The Inadequacy of the Relata-Specific Answer

The general strategy of the relata-specific answer is to explain relating by means of specific adherence, which is considered a fundamental formal ontological relation. Bradley’s regress is supposed to be halted because there are primitively relating entities: relata-specific relational tropes. They are introduced to answer the contemporary modal versions of Bradley’s regress. In them, the main problem is that the existence of a relation and its relata does not entail that the relation relates its relata. No amount of additional relations that do not relate and unify their relata into a relational complex are capable of solving the problem (Wieland and Betti 2008, sec.1). Relata-specific relational tropes, by contrast, are assumed to solve the problem because they necessarily relate their relata and unify them into a relational complex if they exist.

It is the gist of the relata-specific answer to consider specific adherence a formal ontological relation and an internal relation, the holding of which is entailed by the existence of its relata.Footnote 23 Therefore, one does not need to reify it. Moreover, the answer rules out that the relata of a single relation could vary between different possible worlds; every relation is relata-specific. If the relata could vary—as in the case of Russellian relation universals—adherence would not be an internal relation.Footnote 24

The relata-specific answer is prima facie successful in dealing with the contemporary modal version of Bradley’s regress by insisting that specific adherence is a primitive formal ontological relation and internal relation. Nevertheless, in the constitutive Bradley’s relation regress presented in the first section, r’s adherence to a and b is claimed to be constituted by the holding of a non-terminating infinite regress of additional relations connecting relations and their relata. Here, the relata-specific answer would deny the regress triggering claim (Bradley’s trigger). As we noted in the previous section, it is supposed that specific adherence is an internal relation and that relational tropes relate their specific relata without the help of any additional entity. Moreover, the relata-specific answer can be seen providing a metaphysical explanation in which adherence is explained by means of specific adherence: the holding of AD (r, (a, b)) is constituted by the holding of ADs (r, (a, b)) necessarily depending upon the existence of r. It just a part of the metaphysical rock-bottom in the relata-specific answer that there are relata-specific relational tropes among the fundamentally different kinds of entities.

Thus, the relata-specific answer stops at specific adherence: a relational trope is related to its relata by specific adherence, which is not supposed to be an additional relation (contra Bradley’s trigger). Nevertheless, one can present three serious considerations against this view. The first is that by taking specific adherence as a fundamental formal ontological relation, one only asserts against Bradley’s claim that relating is constituted by a non-terminating infinite regress of additional relations. One does not offer any independent reason to believe that there is no constitutive infinite regress. It is not sufficient to stipulate or merely assert that one’s category system has certain fundamental formal ontological relations and that specific adherence is one of them. Additionally, one should be able to provide at least some positive reason for the acceptability of specific adherence as a fundamental formal ontological relation—abductive reasons at least. In other words, one ought to be give grounds for there being relational tropes primitively relating certain specific relata.

Indeed, the second serious worry is that there are substantial reasons to believe that specific adherence is not a satisfactory explanatory primitive. This we can see by comparing it to monadic inherence. It is one of the main motivations of trope bundle-theories to provide a reductive analysis for monadic inherence in terms of less problematic relations such as parthood and co-location. Typically, trope theorists consider inherence a highly problematic, if not an entirely unacceptable, choice for a fundamental formal ontological relation.Footnote 25 A crucial reason for this is that we are not aware of the exact consequences of a mode’s inhering in a substance primitively. Since this inherence entails strong rigid dependence, every mode is strongly rigidly dependence on its bearer. However, one can ask whether a mode such as the redness of a rose is also necessarily co-located with its bearer (the rose), as it seems. What else should be included in inherence, identity-dependence from the mode to its bearer, perhaps?Footnote 26

The things are even less clear in the case of specific adherence. This can be seen by following Lowe’s (2016, 111–2) lead when he complains that (the alleged) relational tropes would not modify or be “in” any particular object. Even though adhering to their specific relata and being multiply rigidly dependent on them, it would be very difficult to say anything else general about the relationship between relational tropes and their relata. Unlike non-relational modes, relational tropes need not be co-located with or spatially close to their relata; the 250-km distance between Luleå and Umeå does not need to be where Umeå and Luleå are—or even close. However, it seems to be implicit in the relata-specific answer that relational tropes are not completely spatio-temporally apart from their relata given the typical view that tropes are concrete: for instance, when the relational trope of 2-m distance exists, also its relata exist. Nevertheless, it would be very difficult to say anything more specific about the spatio-temporal location of relational tropes. Thus, it would be hard to determine how they occur, given they do, as parts of concrete reality. It is a rather elementary requirement for a metaphysical category theory to give such a determination if it is committed to the existence of concreta.

The fact that the relata-specific answer leaves the exact consequences of the holding of ADs (r, (a, b)) largely unsettled gives us strong grounds to doubt the central element of the relata-specific answer that specific adherence is a good candidate for a fundamental formal ontological relation. Rather, a category system introducing such a primitive is inadequate: all that we know about specific adherence can be spelled out in terms of what the holding specific adherence entails. Unless we can specify the exact consequences of a trope adhering to its specific relata, we cannot specify exactly what specific adherence is. This is clearly a fundamental flaw in a putative fundamental formal ontological relation.

In the third place, as was seen above, the holding of specific adherence entails strong multiple rigid dependence but the converse does not hold. Strong multiple rigid dependence determines a more general category of strongly multiply rigidly dependent entities, of which relational tropes might form a sub-category. Strong multiple rigid dependence uniquely characterized by means of distinctness, mereological relations and necessity/possibility can be taken as a fundamental formal ontological relation (Keinänen 2022). This would suggest a reductive analysis of the constitution of specific adherence in terms of multiple rigid dependence and something else: the holding of ADs (r, (a, b)) is constituted by the holding of MRD (r, (a, b)) and something else (necessarily upon the existence of r perhaps).Footnote 27 Unless such a reductive analysis can be achieved, we would have no clear idea of what else is required of a trope adhering to its relata in addition to being multiple rigidly dependent on them, that is, of which specific adherence consists.

Hence, the relata-specific answer provides us with a promising prima facie strategy to deal with Bradley’s relation regress: one attempts to introduce relational entities and formal ontological relations capable of metaphysically explaining the adherence of the relational entities to two or more entities. However, as it stands, the relata-specific answer takes the explanandum—the holding of adherence—in a form of specific adherence as an explanatory unconstituted primitive. Relation r relating two or more entities (the holding of adherence) remains an unexplained mystery because the constitution and exact consequences of the specific adherence of relational trope r to a and b are not spelled out. As Maurin (2010, 321) puts it, “to simply state that relations relate is not enough […] An adequate answer must also include an account of the nature of relations that explains what make them apt to unite distinct relata without vicious infinite regress”.Footnote 28 Our diagnosis is that the relata-specific answer fails to provide such an adequate answer to Bradley’s regress because it does not clarify the holding of adherence in more transparent terms. A successful reductive analysis of the constitution of specific adherence in terms of some other relations, which would follow the model of the trope-theoretical analyses of inherence, would perhaps lead to more satisfactory results. That opens up a new avenue for further research.

5 Conclusion

Bradley’s relation regress raises the question of how to account constitutively for the fact that entity r relates and unifies distinct entities a and b. Accordingly, the regress argument begins with setting up the following explandum: (i) r is an entity of a determinate kind R, (ii) r adheres to a and b, and (iii) r unifies a and b. The regress is created by assuming that (ii) and (iii) can be explained only by postulating entity r1 that relates and unifies r and a, and entity r2 that relates and unifies r and b, and so on and so forth infinitely (or, by postulating r1 as a three-place relation and r2 as a four-place relation and so on and so forth infinitely). The regress argument is premised on the principle that necessarily, if xn relates y and z and unifies them and itself, then xn is related and united to y by means of a distinct entity xn+1 and xn is related and united to z by means of a distinct entity xn+2 (or, on the corresponding increasing adicity or multigrade principle).

The relata-specific answer to Bradley’s regress introduces relata-specific relational tropes, which are primitively relating entities. Necessarily, if relational trope r exists, r adheres specifically to a and b in a certain way and unifies them into the corresponding relational complex. Specific adherence is assumed to be an internal relation and a fundamental formal ontological relation from r to a and b. It determines the categorial nature of r as a relata-specific relational trope. Thus, the relata-specific answer construes r as a relational trope, which is a particular relation of a certain determinate kind, the relation 2-m distance between a and b, for instance.

As we argued in Sect. 4, the relata-specific answer to Bradley’s regress is inadequate. The answer provides us with a promising general strategy to avoid the regress by means of relational entities bearing formal ontological relations to their relata. Nevertheless, because of taking specific adherence as primitive, it leaves (ii) in the explanandum without any adequate explanation. It just asserts against Bradley. The relata-specific answer attempts to explain adherence in terms of specific adherence of a relational trope to its relata. Nevertheless, it only stipulates that specific adherence is a fundamental formal ontological relation determining the ontological category of the trope. Furthermore, we have firm grounds to believe that specific adherence is not a satisfactory fundamental formal ontological relation, that is, an explanatory primitive. We do not know the consequences and constituents of a trope adhering to its specific relata, including the determination of the spatio-temporal location of the trope in relation to its relata. Therefore, it remains unclear what specific adherence is. A successful answer to Bradley’s regress might be constructed by analyzing specific adherence in terms of multiple rigid dependence and some additional relations.

Notes

The other parts are the following: (1) qualities without relations are impossible, or, at least not fully intelligible (AR, III, 21–5); (2) equally with qualities together with relations (AR, III, 25–7); (3) relations without qualities or relata are “nothing” (AR, III, 27).

References to Bradley’s Appearance and Reality are to Bradley 1897, hereafter cited as “AR” followed by chapter number and page number.

Therefore, the problem Bradley’s relation regress poses cannot be solved by putting forward the view, held by some structural realists, that it is possible that there are relations without individual relata (cf. Ladyman 2014, sec. 4). This view violates Bradley’s plausible starting assumption that distinct entities are related and unified.

Following D.C. Williams (1963), we call the relation between relation and its relata “adherence”. Adherence corresponds to the relation of inherence holding between objects and their particular properties (or, modes) such as the -e charge of an electron.

The first version of the relation regress in the Principles of Logic, which was published ten years before Appearance and Reality, is also compatible with this reading (Bradley 1883, 96). In Relations, which is a later text than Appearance and Reality, Bradley is explicit about the unifying function of relating entities. First, he requires that the “relation (even if it is one of diversity) must be between, and must couple, these terms; and the terms must enter into this relation, which so far makes them one.” (658). Later he says that “every case of terms in relation is an individual and unique ‘situation’—a whole” (664; cf. 638). (References to Bradley’s Relations are to Bradley 1935, hereafter cited as “Relations” followed by page number.).

From level 1 onwards, we use also capital letters for typographical clarity. It does not mean that Rn is to be understood as predicates applying to entities rather than naming them.

For a closely similar argument, see The Principles of Logic (Bradley 1883, 96; cf. Allard 2005, 61–6). There is also a version of the relation regress in Chapter II of Appearance and Reality. It has the slightly different form that first we need a two-place relation (e.g. instantiation), then a third-place relation and so on ad infinitum (the adicity of the relations ascends into infinity vs. infinite number of distinct applications of a multigrade relation). This is the way Armstrong (1997, 114), Cameron (2008) and Gaskin (2008, 314–6), for instance understand Bradley’s relation regress. We focus on the form of the regress advanced by Bradley in the chapter discussing relations (III). However, one may assume the increasing adicity if one likes; it does not change anything. The crucial point is Bradley’s trigger: the second step of the argument, which may be reformulated for the increasing adicity version of the argument.

Cf. the task in the problem of universals: what constitutes the holding of exact resemblance of objects? Henceforth, we shall drop “metaphysical” when we speak about explanation, accounting for, constituting or consisting of.

We do not consider Michele Paolini Paoletti’s view of relational modes in this paper (2016). His view denies that there is anything to be explained in the relating business of modes: “you cannot ask for an explanation of the essences of relational modes (including their being relational)” (ibid. 388; Cf. Paoletti 2018). Therefore, he rejects eventually the explanandum of Bradley’s relation regress as something that calls for an explanation. Paoletti’s view is not then a solution or resolution of Bradley’s relation regress problem. Rather, it is denying that there is any (substantial) problem here (of course, this is not an argument against Paoletti).

Francesco Orilia (2009) and Matteo Morganti (2015) have recently defended the tenability of metaphysical infinitism, according to which infinite non-terminating chains of ontological grounding or dependence are able to ground being (cf. Tahko 2014). Morganti’s proposal applied to Bradley’s relation regress is to posit the infinite non-terminating grounding chain corresponding to the tree structure in such a manner that the aRb emerges from the entire chain when the levels of the tree go to infinity. Morganti opposes “the transmission view”, in which relating and unifying is transmitted from a lower level to an upper level (e.g. from (1) aR1r AND rR2b to (0) arb). He thinks that on that view, no relating and unifying would happen because in a non-terminating grounding chain relating and unifying would originate from nowhere. The lowest level does not exist.

The problem in Morganti’s proposal is that his notion of emergence allows that the type of the grounded occurs in the chain. So the type AD (x, (y, z))) can occur in the chain infinitely. Therefore, his proposal cannot answer our argument for the viciousness of Bradley’s relation regress.

Cf. Armstrong 1997, whose term for a fact is “state of affairs”. Some factualists like Bergmann 1967 and Hochberg 1978 add to facts a further constituent, a tie or nexus of exemplification. The existence of a fact amounts to the nexus connecting its terms: a property/relation universal and bare particulars.

We also have a paper advancing a different argument against facts Keinänen, Hakkarainen and Keskinen 2016.

Maurin 2002, 163–6; 2010, 321–3; 2011, 74–5; 2012, 803; Wieland and Betti 2008, 520–2; Betti 2015, ch. 3. Peter Simons (2003, 2010) has also a trope-nominalist answer to the relation regress, but we do not consider it a relata-specific answer. He does not make a vital distinction for the relata-specific answer between specific adherence and existential dependence (cf. below).

This is so notwithstanding their detailed differences in other respects like the general unity problem of the ontological ground for the existence of complex unities.

It is presupposed that r, a and b are numerically distinct from each other and neither a nor b is a proper part of r. Due to this latter presupposition, the dependence is called “strong” in order to distinguish its from “weak” multiple rigid dependence that does not involve the latter presupposition. Moreover, it is a presupposition in using this notion of dependence that r, a and b are contingent existents.

The relata-specific answer rejects then a further presupposition by Bradley that his trigger is due to his formal ontological assumption that relations, given there are some, are existentially independent existences (Allard 2005, 59–66; Candlish 2007, 159; cf. also Maurin 2010, 314; Perovic 2017, sec. 1.2). Stewart Candlish (2007, 159) claims that this assumption is explained by another, categorial assumption: if relations are to be real, they have to be substances and substances are existentially independent entities (cf. Relations, 640, 663).

Although Wieland and Betti do not explicitly speak about dependence, they are also committed to the strong multiple rigid existential dependence of relata-specific relational tropes upon their relata (if there are such entities). This is supported by the fact that Betti says in her recent work that relata-specific relational tropes are specifically dependent on their relata (2015, 93).

In Lowe’s four-category ontology, inherence (or characterization) is one of the two fundamental formal ontological relations.

It does not help to reconstruct Simons’ view by recourse to “the manner of multiple rigid dependence”—as MacBride (2016, sec. 2) attempts to do—because there is exactly one way in which an entity can be multiple rigidly dependent on two or more entities. That type of modal existential dependence does not have modifications.

The rigid dependencies of r, a and b are satisfied by the aggregate of these three entities. It is possible to apply Simons’ (1987, 322) Conditioning Principle to the aggregate of these three individuals and claim that this aggregate forms an additional rigidly independent individual (relational complex). Hence, it does not seem to be necessary to assume unrestricted composition, which is not limited by any principle, to maintain that given the existence of r, a and b, they form an additional individual.

Wieland and Betti (2008) do not explicitly characterize specific adherence as an internal relation and a formal ontological relation. Nonetheless, it is a consequence of their account of relata-specific relational tropes’ relating their relata that these characteristics (in the above mentioned sense) apply to relational tropes’ relating (specific adherence to) their relata.

Wieland and Betti (2008, 519) mention the possibility of relata-specific relation universals, but they do not work out this suggestion in detail. Probably the easiest way to proceed here would be to allow for distinct but exactly resembling relation universals, which could have both distinct and separate groups of entities as their relata, cf. Rodriguez-Pereyra (2017) for exactly resembling universals.

In Lowe’s (2006) four-category ontology, every mode is identity dependent, and therefore, also strongly rigidly dependent on the object in which it inheres. The redness of a rose is strongly rigidly dependent on that particular rose, for instance. Thus, inherence (or, characterization in Lowe’s terms) entails strong rigid dependence.

Cf. the realist explanation of the problem of universals: roughly, the holding of exact resemblance of two objects is constituted by the holding of exemplification of these objects and a universal.

In the same place, Maurin goes on to argue that multiple rigid dependence provides the required explanation, which is not correct as we have just argued. An entity can be multiply rigidly dependent on other entities without adhering to them.

References

Allard, J. (2005). The logical foundations of Bradley’s metaphysics: Judgment, inference, and truth. Cambridge University Press.

Armstrong, D. M. (1997). The World States of Affairs. Cambridge University Press.

Begmann, G. (1967). Realism – A critique of Brentano and Meinong. University of Indiana Press.

Betti, A. (2015): Against facts, Cambridge (Mass.): MIT Press.

Bliss, R. L. (2013). Viciousness and the structure of reality. Philosophical Studies, 166(2), 399–418.

Bliss, R. & Trogdon, K. (2016): Metaphysical grounding. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2016 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2016/entries/grounding/.

Bradley, F.H. (1935): Unfinished draft of the first part of an article on relations (1923–4). In Collected Essays by F.H. Bradley, edited by M. De Glehn and H. H. Joachim. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 630–676.

Bradley, F. H. (1883). Principles of logic. Oxford University Press.

Bradley, F. H. (1897). Appearance and reality (second edition, first edition 1893). George Allen & Unwin.

Cameron, R. (2008). Turtles all the way down: Regress, priority and fundamentality. The Philosophical Quarterly, 58(230), 1–14.

Campbell, K. (1990). Abstract particulars. Blackwell.

Candlish, S. (2007). The Russell/Bradley dispute and its significance for twentieth-century philosophy. Palgrave Macmillan.

Dasgupta, S. (2017). Constitutive explanation. Philosophical. Issues, 27, 74–97.

Gaskin, R. (2008). The unity of the proposition. Oxford University Press.

Hakkarainen, J. (2018). What are Tropes, Fundamentally? A Formal Ontological Account. Acta Philosophica Fennica 94, 129–159.

Hakkarainen, J. & Keinänen, M. (2017). The Ontological Form of Tropes. Philosophia 45(2), 647-658.

Heil. (2012). The universe as we find it. Oxford University Press.

Hochberg. (1978). Thought, fact, and reference: The origins and ontology of logical atomism. University of Minnesota Press.

Keinänen, M. (2022). Lowe’s Eliminativism about Relations and the Analysis of Relational Inherence. In Miroslaw Szatkowski (ed.), E. J. Lowe and Ontology. London: Routledge. pp. 105–122.

Keinänen, M., Hakkarainen, J. & Keskinen, A. (2016). Why Realists Need Tropes. Metaphysica 17(1), 69-85.

Ladyman, J. (2014): Structural realism. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2014 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2014/entries/structural-realism/.

Lowe, E. J. (2006). The four-category ontology – A metaphysical foundation for natural science. Oxford University Press.

Lowe, E. J. (2009). More kinds of being – A further study of individuation, identity and the logic of sortal terms. Wiley-Blackwell.

Lowe, E. J. (2016). There are probably no relations. In A. Marmodoro & D. Yates (Eds.), The Metaphysics of Relations (pp. 100–112). Oxford University Press.

MacBride, F. (2011): Relations and truthmaking. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society 111 (1pt1):161–179.

Maurin, A.-S. (2002). If tropes. Kluwer.

Maurin, A.-S. (2010). Trope theory and the Bradley regress. Synthese, 175(3), 311–326.

Maurin, A.-S. (2011). An argument for the existence of tropes. Erkenntnis, 74(1), 69–79.

Maurin, A.-S. (2012). Bradley’s regress. Philosophy. Compass, 7(11), 794–807.

Maurin, A.-S. (2015). States of affairs and the relation regress. In G. Galluzzo & M. J. Loux (Eds.), The Problem of Universals in Contemporary Philosophy (pp. 195–214). Cambridge University Press.

Morganti, M. (2015). Dependence, justification and explanation: Must reality be well-founded? Erkenntnis, 80(3), 555–572.

Orilia, F. (2009). Bradley’s regress and ungrouded dependence chains: A reply to Cameron. Dialectica, 63(3), 333–341.

Paoletti, M. P. (2016). Non-symmetrical relations, O-Roles, and Modes. Acta Analytica, 31(4), 373–395.

Paoletti, M. P. (2018): Bradley’s regress: A matter of parsimony. In Daniele Bertini & Damiano Migliorini (eds.), Relations. Ontology and philosophy of religion. Milan: Mimesis International. pp. 109–122.

Perovic, K. (2017). Bradley’s regress. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Edward N. Zalta (ed.), https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2017/entries/bradley-regress/.

Rodriguez-Pereyra, G. (2017). Indiscernible Universals. Inquiry, 60(6), 604–624.

Simons, P. (1987). Parts. Clarendon Press.

Simons, P. (2003). Tropes. Relational, Conceptus, 35, 55–73.

Simons, P. (2010). Relations and truthmaking. Aristotelian Society Supplementary, 84(1), 199–213.

Simons, P. (2012). Four categories – and more. In T. E. Tahko (Ed.), Contemporary Aristotelian Metaphysics (pp. 126–139). Cambridge University Press.

Smith, B. (1978). An essay in formal ontology. Grazer Philosophische Studien, 6, 39–62.

Smith, B. (1981). Logic, form and matter. Aristotelian Society Supplementary, 55, 47–74.

Smith, B., & Mulligan, K. (1983). Framework for formal ontology. Topoi, 2(1), 73–85.

Tahko, T. E. (2014). Boring infinite descent. Metaphilosophy, 45(2), 257–269.

Tahko, T. E. & Lowe, E. J. (2020): Ontological dependence. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2020 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2020/entries/dependence-ontological/.

Wieland, J.-W., & Betti, A. (2008). Relata-specific relations: A response to Vallicella. Dialectica, 62(4), 509–524.

Williams, D. C. (1953). On the elements of being. Review of Metaphysics, 7(1), 3–18.

Williams, D. C. (1963). Necessary facts. Review of Metaphysics, 16(4), 601–626.

Funding

Keinänen's research was funded by Kone Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hakkarainen, J., Keinänen, M. Bradley’s Relation Regress and the Inadequacy of the Relata-Specific Answer. Acta Anal 38, 229–243 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12136-022-00516-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12136-022-00516-1