Abstract

The results of an empirical study into the perceptions of “hands-on” experts concerning the welfare of (non-human) animals in traveling circuses in the Netherlands are presented. A qualitative approach, based on in-depth conversations with trainers/performers, former trainers/performers, veterinarians, and an owner of an animal shelter, conveyed several patterns in the contextual construction of perceptions and the use of dissonance reduction strategies. Perceptions were analyzed with the help of the Symbolic Convergence Theory and the model of the frame of reference, consisting of knowledge, convictions, values, norms, and interests. The study shows that the debate regarding animals in circuses in the Netherlands is centered on the level of welfare that is required; the importance of animal welfare is not disputed. Arguments that were used differed according to the respondents’ specific backgrounds and can be placed on a gradient ranging from the conviction that the welfare of animals in circuses is sufficiently warranted and both human and animal enjoy the performance (right end), to the conviction that animal welfare in circuses is negative, combined with the idea that the goal of entertaining people does not outweigh that (left end). The study confirms that perceptions reflect people’s contexts, though the variety in scopes suggests that the (inter)relations between people and their context are complex in nature. Evidence of cognitive dissonance was abundant. Coping strategies were found to be used more by respondents towards the right end of the gradient, suggesting that those respondents experience more ambivalence. This encountered pattern of association between position on the gradient and frequency of dissonance reduction strategies calls for further research on the type of ambivalent feelings experienced. The authors argue that, to come to an agreement about the welfare of animals in circuses, including the way this welfare should be guaranteed, stakeholders from different contexts need to engage in a dialogue in which a distance is taken from right/wrong-schemes and that starts from acceptance of dilemmas and ambiguity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

“Bravo!”…”Bravo!” roars the audience. The curtain is lowered and tomorrow night the same show will take place, due to the enormous success.

Poor, defenseless animals!

Cruel, ignorant audience! (Kesnig unknown, but before 1920)

This passage, translated from a Dutch school book printed at the beginning of the twentieth century, shows that the ethics of using animals to perform in circuses has long been questioned in the Netherlands. In Dutch politics, the welfare of animals in circuses has become a hot topic in recent years: a motion to ban wild animals from circuses has been proposed (and rejected) and numerous parliamentary questions on the subject have been asked. With the aim to learn whether new policies should be developed, and if so, of what kind and how, the Minister of Agriculture commissioned a research project, to investigate possible threats to the welfare of animals in circuses throughout the Netherlands (Hopster et al. 2009). Part of this research was an empirical study of the welfare of these animals in their specific context, from the point of view of “hands-on” experts—the people who handle these animals in daily life, such as trainers, performers, and veterinarians.

Although several studies have been performed internationally on consumer and farmer perceptions of welfare of animals on farms (see e.g., Te Velde et al. 2002; Bock and van Huik 2007) and a start has been made in researching consumer preferences for circuses with animals (Zanola 2008), the perceptions of the welfare of animals in circuses by hands-on experts have not yet been looked into. The case of animals in circuses is nonetheless a very interesting one. Whereas welfare legislation on virtually all other domesticated animals has been enacted, no legislation specifically suited to the situation in circuses exists in the Netherlands. The distinction between “wild” and “domesticated” in circus animals such as camels and elephants is blurred, depending on one’s definition of domestication. And on the whole, the human-animal relation in circuses is a showcase of a relation characterized by asymmetry and ambivalence.

In this paper, we present the results of a contextual analysis of perceptions of hands-on experts concerning the welfare of animals in circuses. As Te Velde et al. (2002) and Schicktanz (2006) have argued in earlier editions of this journal, to study the perceived desirable ways to treat animals and ambivalence herein, a context-sensitive analysis of the human-animal relation is needed, taking historical aspects, values, norms, and socio-economic interests into account. We therefore chose to use the concepts of symbolic convergence, the frame of reference, and cognitive dissonance, as we will elaborate on in the next paragraph. We analyzed the variety of perceptions and moral practice in their contexts and looked for patterns, which we will display in the “Results: Perceptions and Patterns” Section. At the conclusion of the article, besides interpreting the results in the Dutch context, we will discuss the relevance of this research and its results in a wider frame.

Theoretical Framework

The goal of the research into hands-on experts’ perceptions of the welfare of animals in circuses was to provide insights in order to further the political and society-wide discussion regarding the future of animals in circuses in the Netherlands. The central questions of our study were:

-

How do hands-on experts perceive the welfare of animals in circuses?

-

Can we find patterns in the contextual construction of these perceptions?

-

Is there any evidence of ambivalence and, if so, how is ambivalence being dealt with?

We started our study from several theoretical assumptions, focusing on the communicative behavior of our respondents as they made sense of their everyday experiences. In our approach we view people as belonging to groups with accompanying group cultures. Culture is defined as the set of shared, taken-for-granted implicit assumptions that a group holds and that determines how it perceives, interprets, and reacts to its various environments (Schein 1996). A concept such as animal welfare may have different meanings in different interpretive communities (Fish 1980). Cultures thereby rely on the use of communication, with which people regulate their perceptions and behaviors (Pepper 1995). As we were looking for possible differences in meanings given to animal welfare, related to different contexts, this implies that it was not opportune to define animal welfare beforehand.

Bormann’s Symbolic Convergence Theory (Bormann 1985) provides insight in the way perceptions differentiate within cultures. People use language to construct stories to give meaning to the world around them, including the insecurities they experience. By sharing of interpretations in groups of people, a structure is created and language and stories may converge into a shared story. Thus a set of shared visions for a group or a culture can differentiate. We looked for the presence of such socially shared narrations to get more insight into the cultural contexts of the perceptions.

To describe the construction of the respondents’ perceptions, we made use of the model of the frame of reference (Te Velde et al. 2002; Kickert and Klijn 1997; Rein and Schön 1986). According to this model, people’s perceptions are the result of a (largely unconscious) process of tuning of elements of their frames of reference. In this study we distinguished between:

-

values: opinions about what is intrinsically important;

-

norms: translation of values into rules of conduct;

-

interests: including material (economic) as well as immaterial (social, moral) interests;

-

knowledge: constructed out of experiences, facts, stories, and impressions; and

-

convictions: opinions about “the way things are,” assumptions that are taken for granted (Te Velde et al. 2002).

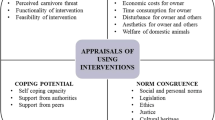

Furthermore, we drew on the Cognitive Dissonance Theory (Festinger 1957). Cognitive dissonance is an aversive drive that causes people to balance opposing viewpoints or cognitions. Cognitions that do not match behavior or other cognitions, are called dissonants; non-opposing cognitions are called consonants. The existence of dissonance reduction strategies shows that people feel ambivalent about discrepant positive and negative aspects of a situation at hand, or are dealing with a deviating presumed other norm that is considered significant. People use several communication strategies to deal with ambivalence in interaction. These strategies are considered instruments for fine-tuning the elements of one’s frame of reference that are in disagreement with each other. During the analysis we looked for the occurrence of these communication strategies, called coping strategies (Festinger 1964; Serpell 1996).

Research Method

Our research was part of a larger research project, for which a scientific committee and a linkage group composed of actors from different fields (e.g., politics, circus practice, animal protection organization) judged and advised the composition and conduct of research. Together we agreed to focus on four specific animal groups, namely big cats, elephants, camels, and horses. These animal groups were chosen because they represent the most commonly used animals in circuses in the Netherlands and cover the (perceived or legally defined) range from wild to domesticated animals. Twenty-nine circuses were active in the Netherlands in 2007–2008, of which eleven had one or more acts with non-domesticated animals. Six of these eleven circuses were selected for the research, on grounds of the presence of the abovementioned animal groups and the number of animals per species. Half of the selected circuses were of Dutch origin (Hopster et al. 2009).

To gain insight into deeper motivations of hands-on experts, we chose to perform a qualitative case-study approach based on twelve structured in-depth conversations. Conventional wisdom of case-study research is dominated by the assumption that a case-study “cannot provide reliable information about the broader class” (Abercrombie et al. 1984). However, we follow Flyvbjerg who argues: “Social science has not succeeded in producing general, context-independent theory and, thus, has in the final instance nothing else to offer than concrete context-dependent knowledge. And the case-study is especially well suited to produce this knowledge (Flyvbjerg 2007: 223).” Furthermore, the case-study approach is extremely meaningful as part of critical reflexivity, what Karl Popper referred to as “falsification”. Popper used the example “all swans are white” and proposed that just one observation of a single black swan would falsify this proposition (Popper 1959; see also Taleb 2007). Because of its in-depth approach the case-study approach is well suited for identifying “black swans”. In line with this, Flyvbjerg stresses the relevance of case-studies based on “the force of example” for gaining knowledge and insight instead of striving after formal generalization and proof (Flyvbjerg 2007). It is, thus, not the number of conversations that allows for formal generalization. Instead we have been searching for patterns emerging within each conversation and showing the relation with the specific context as well as for patterns emerging by comparing the different conversations.

In addition to engaging in conversation with trainers/performers working with animals in the current circus practice in the Netherlands, we selected former trainers/performers, veterinarians that regularly work with animals in circuses, and to get an even more varied picture, an owner of a shelter working with animals from circuses. The respondents were all working with one or more of the abovementioned animal groups. Table 1 shows a bibliographical summary of the interviewees and their relations to practice.

Anonymity was offered, the respondents were approached in an as neutral as possible manner and a natural conversation setting was sought. Socially desirable answering or researcher bias were taken into account by taking the interaction between researcher and respondent as unit of analysis, consequently identifying strategic utterances coming to the fore in this interaction to discern patterns in the perceptions during analysis. Coping with cognitive dissonance, for instance, may be such a strategy, both provoked by and constructed in the very interaction.

The interviews ranged from 45 min to 2 h in length. Three of the conversations were held by telephone, the rest on location, in the daily environment of the respondents. We audio-recorded the conversations with consent of the respondents and digitally transcribed them afterwards.

The conversations were organized according to the method of “laddering” (Bernard 2006; Reynolds et al. 2001). In our semi-structured dialogues, we continuously asked the respondents to make connections between the use of animals in circuses, the consequences thereof (for humans and animals) and the value the respondents attach to that. To reveal underlying motivations for choices that are made and obtain a good description of the criteria, we probed for concrete concepts and asked “why”-questions after each answer until the respondent was unable to give further answers. The outcomes of these conversations are patterns of interconnected convictions, values, norms, knowledge, and interests, in context.

All conversations started with questions about daily practices, later focusing on values and norms concerning the treatment of animals and different aspects of animal welfare. Other questions considered government policy on animal welfare and hands-on experts’ thoughts about the opinions of the public, highlighting knowledge, convictions as well as interests.

Results: Perceptions and Patterns

The perceptions of the current trainers/performers (TP), former trainer/performers (EX-TP), veterinarians (VE) and the owner of a shelter working with animals from circuses (SH), and the frame of reference these perceptions are built on, showed differences and similarities, which we elaborate on in this paragraph.

In reply to what the respondents found important in terms of good animal welfare, training style, housing, exercise, distraction, feed and water supply, and handling of aged and ill animals came to the fore. Apart from the way aged and ill animals should be treated, on which perceptions were widely ranging, the ideas about how things should be in these matters were fairly similar between the respondents. All respondents indicated that animal welfare was important to them and all expressed the need for legislation. The main difference between respondents lay in the levels of welfare that were considered essential, leading to different norms.

The perceptions of current practice in Dutch circuses were rather divergent. In the conversations with trainers/performers, criteria for welfare and the description of current practice were corresponding: in their opinion, the existing situation provides sufficient welfare to the animals. Several respondents outside the group of current trainers/performers described current practice in circuses as unsatisfactory in terms of animal welfare. Respondents in all groups recognized the possibility of the presence of “rotten apples” among circuses, and insisted that these should be addressed properly.

Gradient

Comparing the patterns that emerged within the different conversations we found that most narratives supporting or rejecting animal performance in circuses can be placed on a gradient, ranging from the conviction that the welfare of animals in circuses is sufficiently warranted and both human and animal enjoy the performance (right end), to the conviction that animal welfare in circuses is negative, combined with the idea that the goal of entertaining people does not outweigh that (left end). The perceptions of respondents selected from before mentioned groups (TP, EX-TP, VE and SH) did not coincide with fixed perceptions on this gradient. Nevertheless, there were patterns. On an illustrative scale, the narratives between and within the groups roughly differed in the manner displayed in Fig. 1.

Patterns between and within respondent groups (numbers refer to respondent numbers, as mentioned in Table 1)

Frames of Reference and Symbolic Convergence

Trainers/performers (TP): Looking at the different groups, symbolic convergence seems to be most apparent in the trainers/performers. Their perceptions of animal welfare in circuses correspond to each other in a high degree and seem to be based on a collective tradition with shared convictions, values, norms, and interests, and on knowledge that is derived from comparable upbringing and daily experience in the circus. They displayed parallel visions and a shared story surfaced from their description of the circus culture. The main interests expressed were the continuation of the circus and being able to keep working and living with the animals they perform with. The values and accompanying norms they pronounced corresponds with the current practice in circuses in the Netherlands, mixed with impressions of what they thought the audience would like to see.

Why wouldn’t the animals be in a circus? They don’t have a problem with it, they are being taken care of, they get exercise and they like performing (TD)

The prevailing convictions they articulated were that people come to the circus to see animals, that circuses thus cannot survive without animals, and that the welfare of animals in circuses is sufficiently warranted. Their narratives show that a shift has taken place in the manner of keeping and training the animals, there is more attention for animal welfare compared with the situation in former times.

Former trainers/performers (EX-TP): The story context and frames of reference of retired trainers/performers that were talking about their former working life were comparable to those of the trainers/performers. However, the two former trainers/performers that pronounced to have quit because of an acquired conviction that animal welfare in the circus is insufficient, showed additional items in their frame of reference and symbolically diverged from the narratives used by the trainers/performers. Next to interests concerning the justification of their previous existence—that were equivalent with the interests of current trainers/performers—they pronounced interests that justified the choice to stop and defend a more left end position on the gradient, such as protecting animal interests, and emphasized the lack of a financial interest.

Survival of circuses, ok, but does that have to be at the expense of animals? I think it shouldn’t. And isn’t it the case, that when a small family circus ownes 3 lions, that those 3 lions secure the survival of that circus? That is the other side of the coin, and you can flip that, right? One day those lions will die and then they have to get new lions and train them and then, well, sorry! I say, just think of something else to keep your business going. And that’s that. (EX-TP)

The norms and values these respondents pronounced were norms and values that fitted their new position on the gradient, sometimes mixed with several old norms and values and their convictions were similarly congruent with a higher desired animal welfare than is present in current practice. They referred to knowledge from everyday experience that is reasonably up-to-date (two of the former trainers/performers stopped working recently; one more than 5 years ago).

Veterinarians (VE): For the veterinarians, the division of convictions, norms, and values along the gradient resembles that of former trainers/performers, with convictions regarding animal welfare in circuses ranging from sufficient to insufficient. The norms and values that they expressed were, much more than of the other respondents, scientific in nature and in much detail, especially concerning illnesses, substrate, stress, and feeding.

Circuses are in my opinion better than the wild: animals get older, are vaccinated, de-wormed, there is regulation of disease, food is given, there is no need to hunt, no draughts. Negative sides are the boundaries, but having no boundaries is also stressful and dying in wildlife can be majorly cruel. Of course the traveling stress should be looked into. (VE)

They referred to knowledge from veterinary education and up-to-date knowledge from experience in the veterinary practice. The narrative of the veterinarian working almost solely for circuses fitted that of trainers/performers, positioned at the right end of the gradient, while that of the veterinarian involved with animal welfare and animal protection was clearly positioned towards the left. Symbolic convergence was less visible: several visions were pronounced even in one and the same conversation. This fits a veterinarian’s interest in defending an objective, animal scientific perspective.

One’s ethical norms obviously depend on your frame of reference. That is of course how we deal with companion animals and livestock. You have to see everything set in our current society, in the current time. People with more influence are allowed more. Nobody touches horseries for example (VE)

Owner of a shelter working with animals from circuses (SH): We cannot refer to a set of shared stories when looking at the owner of a shelter working with animals from circuses, because only one interview with such a person was undertaken. However, the narrative shows many similarities with the narratives of other respondents that are positioned somewhat more towards the left end of the gradient, as well as with stories the other respondents told about animal protectors. The main conviction that came to the fore was that the welfare of animals in circuses is not warranted, and can never be, due to the nature of circus life. The pronounced values and norms accordingly were a lot stricter than those of the trainers/performers, up until the point that animals should not be kept in captivity at all.

Animal welfare is the recognition that any species or animal is as we are, they have needs that we’re obligated to provide. It’s their right to have a choice and it’s their right to have a good environment in which to live. (OV)

The knowledge that was being referred to, was based on their own experience with animals in the entertainment industry and on film and photo material of animal welfare organizations and literature on animal welfare. As interest, only the welfare of the animals was articulated, showing the interest in “doing the right thing” in relation to the conviction that animals should be protected.

Dealing with Ambivalence: Coping Strategies

Besides looking for patterns in the elements of the frame of reference and the story context, we have looked at the ways respondents dealt with possible cognitive dissonance. Over the whole gradient, respondents strategically pointed at the interests of other groups: trainers/performers accused people from shelters and animal welfare organizations to be poaching for money, and reversely, over-economizing on animal welfare measures and flattering the macho nature were brought to the fore as interests of trainers/performers. A prominent example hereof was the idea that animal activists give a misrepresentation of the current situation in circuses:

Animal activists tell of a dancing bear in Romania, that is animal abuse, that needs to go. I say that as well. A dancing bear, ring through the nose, pull it, bear has to dance. But they make pictures and then show them here, like ‘that is circus life. That is a circus bear.’ And that’s wrong, that is a lie. That doesn’t happen here. And that’s that. (TP)

A rather defensive attitude regarding the handling of animals in the circus was found in respondents positioned more towards the right end of the gradient, connected to a frequent use of dissonance reduction mechanisms. In the next utterance, for instance, a distinction was made between the norm felt in society and the highest norm:

The people, the normal folk, they don’t see anything wrong. Only the animal activists (TP)

Coping strategies that we have found in the conversations, each illustrated by one or two quotations, are:

-

Eliminating or adapting dissonance

That traveling doesn’t bother them one bit. That’s a load of bullshit. (TP)

How we train the animals? An iron stick, and then we hit them. Hah hah! Until they do what we say. Hah hah! That is what the animal activists say. No, if we mistreat an animal, it becomes scared. (TD)

-

Adding consonants to behavior

Why would animals not be in a circus? They don’t have any problems with it, they are taken care of, get exercise and they like what they do (TP)

-

Amplifying consonants

The animals here become older than in the wild. Why? Well, because we are following them all day and as soon as something is wrong, o boy, we call the vet. (EX-TP)

We love the animals. They have a better life than most poor children do at home. (TP)

-

Trivializing dissonance

There’s only a handful that makes a fuss about it [about animals in the circus, ed.] (EX-TP)

A lion in the free wild moves when he needs to eat, otherwise he’s just sun tanning. So it doesn’t always need exercise. (EX-TP)

-

Trivializing the current situation by comparing the condition of animals in the circus with other settings

Horses have a worse life in many riding-schools than in the circus. (TP)

Private breeders, they treat their animals like hell. I’ve seen it with my own eyes. And that are things, then

I wonder why some people have the nerve to badmouth circuses. (TP)

A chicken farm, that’s animal suffering! (TP)

-

Shifting responsibility

Well, the space problem, that’s not us, it’s the municipalities that give us tiny spots for example. (TP)

I would love to have the possibility to take my animals to the forest or the beach, but that isn’t really being offered. (TP)

Coping strategies also occurred on the left end of the gradient, though less frequently: looking at the narratives as present in the different conversations, the number of times coping strategies were used by respondents at the right end of the gradient was approximately fourfold the incidence towards the left. Dissonance reduction by respondents positioned more towards the left end of the gradient dealt predominantly with the perceived trivializing of the situation of animals in circuses by others:

Circuses did suggest rules on their own. Rules that have not been approved by the RDA. Why not? Because they have just described what they are currently doing, that is what they see as the ideal situation. And besides that, they don’t even do what they have written down. (VE)

Imprisonment is not acceptable whatsoever, in my opinion. But if you would have to make a choice, the worse imprisonment situation is by all means the circus, because they live in such small cages that they cannot perform their naturally desired behaviour. In the worst zoo, they at least have some choice. […] Especially during transport, the animals are deprived of practically all basic needs (SH)

Conclusion and Discussion

In the previous paragraphs, we have described the variety of perceptions of the welfare of animals in traveling circuses in The Netherlands from the point of view of “hands-on” experts in their specific contexts, and have distinguished several patterns in perceptions and dissonance reduction.

It is evident that the perceptions of trainers/performers, veterinarians, people with animal shelters, and of animal protectionists/activists and in society, differ—and sometimes clash. Obviously, animal welfare is a contested matter, shown by divergent perceptions in which interests, norms, and values differ, and knowledge is not always unambiguous. Interestingly, all respondents indicated that development of legislation on treatment of animals in circuses is necessary. The essence of the dispute is not whether animal welfare is important, it is about the level of welfare that is required: what people think an animal does and does not want and appreciate, what is natural, and what is and is not permitted morally. The desired nature of the norms in legislation coincided with the desired level of welfare.

Evidence of cognitive dissonance was abundant. The use of dissonance reduction strategies shows that respondents are aware of a presumed social norm that deviates from their own current norm (yet is considered significant), or feel ambivalent about their relation with the animals at hand. More frequent use of these strategies by respondents that tend to support the stance “the welfare of animals in circuses is sufficiently warranted and both human and animal enjoy the performance,” suggests that these respondents experience more ambivalence. Both the divergent perceptions on animal welfare and the encountered defensive attitude and the firmness with which people state their opinions seem to stand in the way of a joint debate: people bury themselves in their own viewpoint. Especially in the face of perceived threat (i.e., a perceived differing norm on the welfare of animal in circuses) people tend to show self-referential reasoning, resulting in incompatible standpoints (Haslam 2001).

To come to an agreement on the welfare of animals in the circus, whether or not aimed to result in new policies, the different stakeholders need to engage in a shared debate and try to find agreed-upon criteria for judging animal welfare. Such a debate may provide insight in the differences and similarities between each other’s contexts and the construction of each other’s frames of reference (especially concerning values, norms, convictions, and interests). A well-organized communication process may facilitate in bringing the stakeholder groups together and allow new interpretive communities to arise. As Pearce and Littlejohn (1997) explain, negotiation, bargaining, and mediation are popular forms for argument and intervention. But these forms will only be effective when the parties to a dispute share sufficient common ground for discussion (Gray 1989). Developing common ground for more constructive discussions and interest based negotiation (Fisher and Ury 1981) is a difficult process that requires recognizing, explicating, and discussing different perceptions, related to different backgrounds on the one hand, and demarcating the problem domain, such that it becomes workable and acceptable for the parties involved. The desired communication form is a dialogue, in which the stakeholders take a distance from right/wrong-schemes and in which dilemmas and ambiguity are accepted. Such a dialogue forces people to research differences in backgrounds and perceptions, and acknowledge mechanisms like dissonance reduction, thus opening possibilities of shifts in contexts and shared frames of reference (Pearce and Littlejohn 1997).

When viewed as a case study on human-animal relations, our findings in the circus context in the Netherlands show that this relation is indeed one characterized by asymmetry and ambivalence. In a wider frame, our study confirms that perceptions reflect people’s contexts, though the variety in scopes depicted in our gradient model suggests that the (inter)relations between people and their context are complex in nature. The encountered pattern of association between position on the gradient and frequency of dissonance reduction strategies is an interesting one and calls for further research on the type of ambivalent feelings experienced. If, for instance, more ambivalence concerning the relation with animals is felt when this relation is more asymmetrical, even in situations where there is little or no conflicting social norm, this would imply the existence of an inherent feeling of unease about the domination of humans over animals. Nevertheless, the connection that we observed between the judgment of the existing situation, pronounced desired norms in legislation and interests, that came to the fore in different respondent groups, suggests that Spinoza (1677) may still be right when stating that “we don’t desire what is good, we judge as good what we desire.” Realizing this, we conclude that the issue of animal welfare in circuses is a complex ethical problem that will not be solved as long as we do not commonly accept it to be such a problem.

References

Abercrombie, N., Hill, S., & Turner, B. S. (1984). Dictionary of sociology. Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin.

Bernard, H. R. (2006). Research methods in anthropology: Qualitative and quantitative approaches. Lanham: Rowman Altamira Press.

Bock, B. B., & van Huik, M. M. (2007). Animal welfare: The attitudes and behaviour of European pig farmers. British Food Journal, 109(11), 931–944.

Bormann, E. G. (1985). Symbolic convergence theory: A communication formulation. The Journal of Communication, 35(4), 128–138.

de Spinoza, B. (1677). The ethics. Part III, scholium to Proposition 9.

Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Festinger, L. (1964). Conflict, decision, and dissonance. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Fish, S. (1980). Is there a text in this class?: The authority of interpretive communities. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Fisher, R., & Ury, W. (1981). Getting to yes: Negotiating agreement without giving in. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

Flyvbjerg, B. (2007). Five misunderstandings about case-study research. Qualitative Inquiry, 12(2), 219–246.

Gray, B. (1989). Collaborating. Finding common ground for multiparty problems. San Francisco: Jossey Bass.

Haslam, S. A. (2001). Psychology in organizations; the social identity approach. London: Sage.

Hopster, H., Dierendonck, M. V., Brandt, H. V. D., & Reenen, K. V. (2009). Welfare of animals in travelling circuses in the Netherlands; Circus practice in 2008 Report. Lelystad: Animal Sciences Group of Wageningen UR.

Kesnig, H. (unknown, but before 1920). Levende requisieten. In T. v. d. Blink and J. Eigenhuis (eds.), Op zonnige wegen, Groningen/Den Haag: J.B. Wolters, 85–90.

Kickert, W. J. M., & Klijn, E. H. (1997). Managing complex networks: Strategies for the public sector. London: Sage.

Pearce, W. B., & Littlejohn, L. W. (1997). Moral conflict. When social worlds collide. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Pepper, G. L. (1995). Communicating in organizations: A cultural approach. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Popper, K. (1959). The logic of scientific discovery. New York: Basic Books.

Rein, M., & Schön, D. A. (1986). Frame-reflective policy discourse. Beleidsanalyse, 15(4), 4–18.

Reynolds, T. J., Dethloff, C., & Westberg, S. J. (2001). Advancements in laddering. In T. J. Reynolds & J. C. Olson (Eds.), Understanding consumer decision making: The means-end approach to marketing and advertising strategy. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Schein, E. H. (1996). Culture: The missing concept in organization studies. Administrative Science Quarterly, 41(2), 229–240.

Schicktanz, S. (2006). Ethical considerations of the human–animal-relationship under conditions of asymmetry and ambivalence. Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics, 19(1), 7–16.

Serpell, J. (1996). In the company of animals: A study of human-animal relationships. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Taleb, N. N. (2007). The black swan—The impact of the highly improbable. New York: Random House.

Te Velde, H., Aarts, N., & Van Woerkum, C. (2002). Dealing with ambivalence: Farmers’ and consumers’ perceptions of animal welfare in livestock breeding. Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics, 15(2), 203–219.

Zanola, R. (2008). Who likes circus animals? POLIS Working Papers, 127.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the anonymous reviewers of an earlier version of this paper for their helpful comments.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Nijland, H.J., Aarts, N.M.C. & Renes, R.J. Frames and Ambivalence in Context: An Analysis of Hands-On Experts’ Perception of the Welfare of Animals in Traveling Circuses in The Netherlands. J Agric Environ Ethics 26, 523–535 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10806-010-9252-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10806-010-9252-8