Abstract

This qualitative study explores how business leaders narrate their personal ways of recognizing, reasoning, and resolving moral conflicts and what these stories reveal about their moral identity processes within organizational contexts. Based on interviews with 25 business leaders, 4 moral identity statuses were identified: achievement (commitment to a personally meaningful moral value framework that had been established through a period of self-exploration), moratorium (self-exploration of one’s moral value framework that was ongoing), foreclosure (commitment to a given moral value framework that was present with little or no personal self-exploration), and diffusion (neither clear commitment to nor exploration of a personal moral value framework was present). The moral identity statuses were based on how leaders approached and interpreted moral conflicts and what the influence of the organizational context was in their moral decision-making processes. Some remained steadfast in adhering to their previous value commitments, while others tried to avoid taking any clear moral standpoint. Still others experienced moral conflicts as disequilibrating events that triggered reflective processes and developmental cycles of moral identity change. These moral identity statuses hold implications for facilitating moral identity development among business leaders in the context of work.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Contemporary understandings of business leadership acknowledge that effective management cannot be reduced to a morally neutral stance that focuses only on achieving organizational ends without ethical considerations (see, for example Nielsen 2006). Rather, being a leader includes “the management of meaning” (Smircich and Morgan 1982). Regardless of their official, hierarchical position as managers, leaders can be defined by a potential to influence others (Day and Harrison 2007). Leaders elicit processes of identification and act as role models for others (Zhu et al. 2016). Because of this influential position, responsibility and morality are an inherent part of leadership.

Moral identity provides a central concept for understanding the moral core of leadership, as it refers to a strong sense of being a moral person and to the importance of moral values to an individual (e.g., Aquino and Reed 2002; Hardy and Carlo 2011a, b). Thus, moral identity motivates people to take moral actions (Hardy and Carlo 2005; Mayer et al. 2012). Because moral identity can act as a strong motivator for personal moral behavior (see, e.g., Detert et al. 2008; Greenbaum et al. 2013; Mayer et al. 2012; Shao et al. 2008; Skarlicki and Rupp 2010), it has sparked interest also in the organizational leadership domain (e.g., Mayer et al. 2012; Skubinn and Herzog 2016; Zhu et al. 2016). A moral leader should be a moral person who shows integrity and consistent, principled decision-making (Brown and Treviño 2014). However, there is little understanding of the processes that relate to moral identity development and moral maturity among adults (Krettenauer et al. 2016). How do business managers become ‘moral leaders’?

There is also very limited evidence of the influence of the context in which these moral identity processes occur: how do adopting and applying personal moral values actually occur within organizations (Jennings et al. 2015)? This dearth of information is a significant problem, as organizational pressures for optimizing effectiveness can deter leaders’ moral behaviors by limiting one’s ability to discern right from wrong and restraining one’s capacity to act according to what is ethical. Thus, the organizational context could potentially prevent one from practicing moral leadership behaviors (Nielsen 2006) and represent a potential barrier for moral identity development. On the other hand, organizations can also provide positive elements such as ethical role models or a strong ethical culture that can support and strengthen moral identity among both leaders and employees (Weaver 2006; Zhu et al. 2016).

The aim of this study was to examine moral identity processes among business leaders within their organizational contexts. Since moral identity cannot be observed directly, we used moral decision-making processes (i.e., moral identity exploration and commitment) to postulate various underlying dimensions of moral identity. The practice of examining identity-related decision-making processes has been commonly used to study underlying dimensions of ego identity more generally (e.g., Marcia et al. 1993). Identity, can be seen as a form of adaptation between person and context, where conflict is needed to trigger identity change (Bosma and Kunnen 2001). In line with this reasoning, moral identity processes are likely to be triggered by moral conflicts, which offer a relevant context for studying these processes. To summarize, we investigated how middle managers and executives narrated experiences of confronting and resolving moral conflicts and what these narratives revealed about their moral identities.

Theoretical Framework

Identity and Moral Identity

Identity is the culmination of an individual's values, experiences, and self-perceptions, of the meanings that individuals attach to themselves and to their interactions with their contexts (Erikson 1964). Identity is developed and sustained in social interaction, especially as the integration of different experiences of the self in challenging environments. This personal search addresses the question ‘who am I?’, and it results in a self-conceptualization that can range from relatively simple and unsophisticated understandings of oneself to complex and integrated perceptions (Day and Harrison 2007).

People have multiple identity components which may become activated in different contexts; here, our interest is in moral identity in the context of work. Generally, the definitions of moral identity involve a personal sense of morality and the degree to which being a moral person is important to an individual’s identity (for reviews, see Jennings et al. 2015; Shao et al. 2008). Thus, moral identity can be understood as “a self-conception organized around a set of moral traits” (Aquino and Reed 2002). Individuals whose identity is centered on morality will show high motivation for moral actions, because they experience the desire to live according to their core sense of self (Hardy and Carlo 2005). The degree to which a set of moral traits is central to one’s identity is referred to as internalization, whereas symbolization refers to the degree to which these moral traits are expressed publicly (Aquino and Reed 2002). However, we have a rather limited understanding of the processes through which individuals can attain a strong and mature moral identity. Ideally, a higher level of moral centrality develops through a process of integration (Blasi 1995), whereby the individual’s sense of self is infused with moral convictions that provide the basis for moral behavior (e.g., Hardy and Carlo 2011a; Lapsley and Hardy 2017). But how does this integration take place?

Commitment and exploration have been identified as core processes of identity formation more generally, capturing personal identity-related decisions one makes in different life domains (see, e.g., Bosma and Kunnen 2001; Marcia 2002). Exploration is defined as the process of examining different identity alternatives that might be compatible with one’s own interests, talents, and values, and commitment is defined as having made an identity-defining decision to which one intends to adhere for the foreseeable future. Thus, although identity cannot be observed directly, processes of exploration and commitment that individuals describe in their identity decision-making can be considered indicators of underlying dimensions of one’s general identity (Kroger and Marcia 2020). However, this approach has not yet been used extensively to understand more about the processes of moral identity development in adulthood (Lapsley and Hardy 2017). We will next review theoretical underpinnings between moral identity and the context in which identity processes are likely to take place: the organizations where leaders act and the moral conflicts that they are likely to face as an inherent part of their work.

Moral Identity Processes in Context: Organizations and Moral Conflicts

Within organizations, leaders can encounter constraining and/or enabling contexts that help determine the options for moral actions available to them. For example, coherent and prominent ethical organizational norms can support moral actions, but less coherent or less-than-ethical organizational norms (e.g., if an organization emphasizes short-term monetary value over ethical considerations) can constrain leaders’ moral behaviors by providing little scope for individual moral consideration (Weaver 2006). Thus, leaders can face tensions that arise from coming to terms with various social roles and norms in different contexts and maintaining a coherent self-image at the same time. When people try to resolve the tensions between less and more context-appropriate or desired selves, these efforts are referred to as identity work (Brown 2015; Watson 2008).

Identity work is “more necessary, frequent and intense in situations where strains, tensions and surprises are prevalent, as these experiences prompt feelings of confusion, contradiction and self-doubt, which in turn tend to lead to examination of the self” (Brown 2015, p. 25). Moral conflicts can represent such situations, as they often involve several competing, controversial, and/or conflicting perspectives regarding the best resolution. Leaders are especially susceptible to facing these kinds of tensions, because leadership is always embedded within interpersonal relationships; a leader without a social context simply cannot be a leader (Day and Harrison 2007). Leaders have numerous commitments to different roles, with potentially conflicting expectations from different stakeholders, and such circumstances can challenge leaders’ abilities to act according to their own moral identities.

If a leader’s values are not compatible with external expectations or the demands of an organization, or he or she cannot express personal moral values in actions, a potential threat to a leader’s moral identity may occur. Thus, moral conflicts can represent disequilibrating events, where one’s existing values and ways of thinking are challenged (Marcia 2002). However, this challenge can also precipitate change by opening up the possibility of development towards new and more mature, as well as more nuanced, forms of identity. Thus, moral conflict can trigger an identity reformulation phase. However, this moral identity meaning construction requires the capacity for both self-reflection and the critical examination of established social and organizational orders (MacIntyre 1999, see also Wilcox 2012). Therefore focusing on moral conflicts in more detail could produce insights into how leaders actually reflect upon the moral problems they have faced and the efforts that they have applied to learn from these experiences. These issues are central to understanding how individuals construct their identities (see, e.g., Ashforth and Schinoff 2016), because identity, including moral identity, is not something that one can observe directly. As Kroger and Marcia (2020) have noted, one can infer something about one’s identity by the way in which identity-defining decisions are made. Therefore, we focused on leaders’ narratives of their encounters with moral conflicts and the moral decisions that they made (or not) as a means of learning about underlying dimensions of moral identity.

Research Aims

The purpose of this study was to investigate how leaders’ moral identity was constructed through retrospective descriptions of personally meaningful moral conflict at work. Qualitative research methods were adopted in order to understand what these descriptions indicated about their moral identity processes. Although our study design did not allow us to examine leader moral development over time on a longitudinal basis, our premise was that by investigating the retrospective stories leaders described about their meaningful encounters with moral conflicts, we could obtain important information about how leaders’ moral identities were constructed and developed and/or maintained within organizations.

Thus, we investigated whether or not moral conflicts could trigger moral identity development and what kinds of typical moral identity patterns (progression, regression, or stability) appeared in these stories. More specifically, we wanted to learn about leaders’ personal value commitments and any exploration of these values, the salience of morality to the self, and the role of context in which moral decisions occurred in order to understand how contexts might facilitate or impede moral identity change. We posed the following general research question for our study: How do business leaders describe their moral identity processes in situations of moral conflict at work?

Method

Participants

The data was collected from two distinct sources in Finland: managers (N = 17) in a large public sector organization with multiple service areas (i.e., education and health care) and a group of executive Master of Business Administration (eMBA) participants (N = 8), an education program targeting experienced business managers with at least 3 years of work experience in a managerial or supervisory position. All participants worked with stakeholders (i.e., employees, management, customers, media) and had direct subordinates; thus, they were important decision-makers and role models in their organizations. Within this context, their personal moral identity could have far-reaching effects on the morality of their entire organizations and the employees in them (Brown and Treviño 2006, 2014).

An invitation to participate in the study was sent by email via contact persons to each leader in the public sector organization and to all participants in the eMBA course. The invitation included a description of the study aims and procedure, as well as information about confidentiality. All participants were asked to contact the first author directly to receive further information about the study and to arrange an appointment for the interview if the individual wished to proceed. All the individuals participated on a voluntary basis. Data collection included the individual semi-structured interviews that were conducted by the first author and a questionnaire that was administered to the participants after the interview; the questionnaire included demographic background questions and an informed consent form. To summarize, the invitation to participate was addressed to individuals who worked in formal managerial positions. However, based on our conceptual definition of managers and leaders, regardless of their hierarchical position in middle or upper management, we will hereafter refer to all study participants as leaders. This decision was made because of their influential roles within their organizations and their responsibilities for others (e.g., followers, clients, and colleagues).

A total of 25 leaders (12 men and 13 women) were interviewed. The participants’ ages ranged from 36 to 65 years, with a mean age of 49 years (SD = 8.5). They worked in the public sector (19), private companies (3), or had their own companies (3). Participants had a mean of 47 direct subordinates (range 5–300, SD = 66), and their working experience in the current job varied from 1 to 40 years, with a mean of 9 years (SD = 9.4). For reporting purposes, pseudonyms were given to each participant from among the most common first names in Finland.

Procedure

Because we wished to study moral conflicts that may evoke a disequilibrating state and trigger moral identity change (Bosma and Kunnen 2001), we chose to use the critical incident technique (CIT; Butterfield et al. 2005; Flanagan 1954) as the primary means of gathering interview data for our study. The CIT involves collecting personal self-recollections of different incidents, which can provide a rich insight into the phenomenon that is under investigation (Gremler 2016). In the current study, the CIT was conducted using semi-structured interviews focusing on personal reflections related to an actual moral conflict that the participant had experienced. The participants were asked prior to the interview to consider a conflict that they would be willing to share during the interview. In this way, we aimed to elicit stories about personally meaningful events, as the participants had the possibility to choose the incident they wished to discuss. The following descriptions and questions (the themes that guided the semi-structured interview) were sent to the participants by email before the meeting. First, the following definition was presented to the participants:

An ethically problematic situation means that the decision-maker does not know what would be the right thing to do, or he or she cannot act according to what they see to be right for one reason or another. The decision also includes a choice between options that are equally good or equally bad. Solving the ethically problematic situation has consequences for others: either to the subject of the decision, possibly collateral individuals, or to the decision-maker him/herself. Time pressures, conflicting expectations, interests, and values often are involved in these decisions.

Because leaders act in social contexts and because their organizations can provide several factors which might constrain and/or enable their moral behaviors and moral identities (such as different opportunities for modeling, identification, and learning), the interviews aimed to investigate the role of the organizational context in moral conflicts, an issue neglected by most previous studies of moral identity (Schwartz 2001; Weaver 2006). The semi-structured interview asked the following questions: (1) “Please think thoroughly about your experiences of ethically problematic situations in your work. Describe one situation in as much detail as possible that you experienced as ethically problematic.” If the participant did not spontaneously describe the following aspects, each was probed separately: “Why did you find the situation ethically problematic?” “Describe the circumstances under which the situation took place.” “What did you do to solve the problem?” (2) “What influence (if any) did the following factors have on your decision-making and your attempts to resolve the problem?” The latter question was aimed to evoke descriptions about how different contextual factors had affected moral decision-making in the situation. The factors were based on the framework of Weaver (2006): (a) your organization or other institutions (e.g., professional networks, professional ethical guidelines, ethical codes), (b) your supervisor or upper management, (c) your colleagues or subordinates, (d) your personal values and (work) experience, (e) situational factors, (f) other factors (e.g., other than work, such as family).

Each of the participants was able to identify and discuss at least one conflict situation that they regarded as ethically problematic. If the participant described two different events, the one that was discussed in more detail during the interview was used in the analysis. The interviews lasted from 23 min to over an hour (mean duration 42 min); interviews were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim.

Analysis

We analyzed the data using a three-step inductive content analysis (Berg and Lune 2012; Elo and Kyngäs 2008; Miles and Huberman 1994; Strauss and Corbin 1998). The first step of the analysis was the preparation and unitizing phase, where the transcripts were broken down into meaning units (e.g., Butterfield et al. 1996; Gioia and Sims 1986). The first and second author read all the interviews in order to find common themes related to the way individuals described their chosen moral conflict and how they had tried to resolve the situation. The aim was to identify distinguishable themes of how the managers described experiencing the moral conflict and what kinds of thoughts, perceptions, and values they had before, during, and after the moral conflict occurred. Two main themes were found: the first related to the content of the moral conflict, the second to the personal processes that took place when trying to resolve the conflict.

In the second step, organizing and categorizing, the first two authors took part in an iterative, intersubjective process. They discussed the similarities and differences among thought units and organized them into further categories. Here, the main conclusion was that the personal processes found in the data could be classified into different combinations of moral identity commitment and exploration. Exploration was defined as the process of examining different moral identity alternatives that might be compatible with one’s own interests, talents, and values, and moral identity commitment was defined as having made a moral identity commitment to which one intends to adhere for the foreseeable future. At this point these moral identity categorizations were discussed and finalized in agreement with the third author.

The third and final step was classification and abstraction. In some of the stories, we were able to identify a cycle that took place over time related to the personal moral exploration and commitment processes that the leaders described. Some described their identity-related values, thoughts, and feelings (1) before they were confronted with the conflict, (2) during the event, and (3) after the conflict. For some, there was an identifiable change in values, thoughts, or feelings that occurred over this process. We found that reconsideration and reconstruction of previous value commitments may be generated in the course of addressing a moral conflict, including some domain-specific factors related both to moral issues and to the organizational context that affected the moral identity processes.

Results

Moral Identity Statuses Identified Through Moral Conflicts

When the leaders discussed their critical incidents (i.e., moral conflicts) and how they approached resolving them, the focal themes within their narratives related to two main processes of moral identity formation: commitment and exploration. The narratives fell into four distinct groupings, based on the firmness of commitment to a certain moral value framework and on the personal exploration and prioritization processes that were used in order to develop a personally meaningful value framework. As we describe below, these processes were found to be comparable to the four identity statuses described in the general identity literature (Marcia 1966, 2007; Kroger and Marcia 2011): achievement (commitment is present after a period of self-exploration), moratorium (commitment is absent, while self-exploration is ongoing), foreclosure (commitment is present with little or no personal self-exploration), and diffusion (neither commitment nor self-exploration are currently present). However, we also identified some context-specific features related to moral identity processes, in particular, which we will next describe in more detail.

Moral Identity Diffusion

In our data we found a group of leaders (N = 6) who did not describe a clear moral framework that served as the basis of their decision-making, nor did they try to develop such a framework. Rather, moral conflicts for the leaders in this group were experienced as ongoing uncertainty about how to make moral decisions. For example, Ritva wanted to be a flexible leader who was open to others’ opinions, but she described constantly wondering whether to follow organizational guidelines or to give more freedom and responsibility to the employees:

For me, being an engaging leader means that I am willing to change my decision if someone has a better idea. I am not the kind of person who just makes a decision and regardless of other, clearly better ideas, still refuses to even consider them. Therefore, if it feels right, of course I can change my mind. It is my way of being a leader. (Ritva)

Ritva struggled between using formal rules as a basis for her decisions, and at the same time wanting to show trust by actually leaving the decision-making to her employees:

I try to resolve conflicts so that I can find justifications for my decisions in the organization’s rules. So that my choices would not be based only on my personal judgment, but that there is something I can rely on; why I am making the decision in a certain way. However, of course I leave it to the employees to follow these guidelines. (Ritva)

She also described being unable to make any final decision about how to deal with employees who smoked within a youth work facility during their breaks, which was against the facility’s formal rules related to substance abuse prevention. Ritva’s uncertainty persisted as a continuous challenge:

Should I confront my employees as being the leader and make them feel uncomfortable? Or should I take a step back and trust their professional skills and see how they deal with the situation? I think this is the difficult question. … This discussion about workplace rules arises at regular intervals. (Ritva)

Another example comes from Tarja, who talked about a moral conflict that involved planning work time schedules that would be fair for two employees with different needs. She described postponing the decision as a way of refraining from taking responsibility for it:

Sometimes difficult situations resolve themselves. There is still some time before I have to make this decision – I mean, what if I have put all this time and energy into finding a solution, and then the employee finds another job and leaves here, which solves the problem? Or maybe as time passes the employee does not see this as a big issue anymore, maybe she will adjust to the current work schedule. Maybe the problem will go away. I mean, there are so many other things on my agenda, perhaps this is resolved over time. (Tarja)

We identified these leaders as moral identity diffused, as they did not have a clear idea of what was central to their personal moral identity. They described ongoing uncertainty about how to reach compromises between competing interests (such as supporting employee autonomy versus following the rules and formal policies that governed workplace behavior) and did not make efforts to establish a moral framework, either.

In Marcia’s typology (2002), diffusion refers to individuals who lack both identity-defining commitments as well as exploration of different identity alternatives. In a similar manner, morally diffused leaders were likely to drift without clear commitments to a consistent set of moral values to guide one’s thoughts or actions. Rather, they were likely to simply ignore moral conflicts, pass the responsibility to someone else, or in other ways distance themselves from any potentially disequilibrating event (such as Tarja did by postponing her decision). Their moral conflict descriptions (i.e., critical incidents) mostly dealt with everyday struggles instead of telling a coherent story of a specific conflict that had challenged their moral value frame. They also did not describe a clear moral decision after their period of uncertainty.

Moral Identity Foreclosure

Based on our qualitative analysis, some leaders (N = 7) talked about strong commitments regarding their moral values, without prior periods of uncertainty or exploration. These situations often appeared in authoritarian contexts, where the leader chose to accept the guidelines, expectations and orders that came from higher up in the organizational hierarchy, such as from upper management, without question. These leaders did not consider the organizational guidelines or expectations in relation to their own values nor try to find alternative ways to interpret a specific guideline. For these leaders, organizational contexts had specific elements that restricted leaders’ moral decision-making, as Timo described:

If I accept the decision made by my supervisor, of course I also personally commit to it; it becomes also my decision. And when the decision is made, it is no longer my role to question it. I guess my military-related background affects how I see these things. That even complicated things can be handled quite simplistically; it is either-or. I am very direct, when it comes to breaking the rules. We have certain protocols on how to deal with it. When the threshold of a wrong-doing has been crossed, we always follow the same procedure, period. (Timo)

Here, Timo describes his own background with firm values which are combined with and strengthened by his work context that also had clear norms and guidelines. Another example came from Markku, who described how he saw himself as a representative of the employer and thus carried out employer decisions even when he did not agree with them:

I have to trickle down the decisions that come from above me. I need to carry the decisions forward [to my employees] and act in line with them, even decisions that I do not agree with. I’ve been trying to explain this to the employees, but they disagree with all these economic restrictions. However, these restrictions influence our work, and I need to follow them through. After all, I am a representative of my employer, and I have to take things forward. I have to remember this all the time, in the back of my head; I represent my employer. (Markku)

Like Markku and Timo, leaders who resolved moral conflicts based on solely on external demands were identified as having foreclosed moral identities. In Marcia’s model (2002), foreclosure refers to identity commitments which are formed with little or no personal self-exploration. Similarly, morally foreclosed leaders had clear norms that they felt important to follow and saw no need to personally consider the norms or any other perspectives or actions outside of this value framework. They were thus reluctant to genuinely listen to various or alternative views:

The employees might think that hearing their concerns means that the decision will be made according to their wishes. But even though they’ve had the opportunity to state their opinions, my decision might still be different, depending on what the organization demands. (Kari)

Thus, leaders with a foreclosed moral identity may be resistant to identity development in a rigid way, avoiding or denying any information that might contradict their adopted values. In our data these values were related to what the organization emphasized (as in Kari’s citation). In line with Marcia’s model (2002), leaders with a foreclosed moral identity seemed to have developed a personality structure built to prevent disequilibration; they would therefore be less likely to re-evaluate their present value commitments.

Moral Identity Moratorium

Only one of the leaders in our data was identified as being actively processing and exploring her values to (re-)establish a personally meaningful moral value framework in the employment context. Marja described a clearly distinguishable moral problem where she had taken personal efforts to find a resolution to the situation but concluded with a compromise and thus experienced an ongoing moral conflict:

I see that one of our employees is not being valued or accepted by others. I see that she is being judged and treated with prejudice because of her national background. Because she is different than others. (Marja)

Marja described how she realized that her actions reflected her values, but she still struggled in finding a way to make the right moral choice (representing exploration). She was in the process of trying to resolve the issue:

I think this is a problem that we need to discuss more with the employees. I should emphasize that we can have all kinds of people working here. But I don’t feel so certain about this. I would like to do the right thing, to give her a permanent job here, and show that I value those qualities that she has. And I hope that others would value them as well. So that those characteristics that make her different would not be experienced as disturbing or difficult. -- But I haven’t brought up this issue yet. What I’ve tried to do about it is to think how to approach the issue [with the employees]. (Marja)

Instead of leaving the situation unresolved or placing the responsibility on others (as diffused leaders might do), Marja decided on a compromise in her actions:

I have decided on a compromise, where this employee is currently employed here, but only with a contract for a few months at a time. There are also actual justifications for this, as there have been a lot of short-term substitute positions open. But I haven’t hired her as a permanent employee, although there have been those openings as well. (Marja)

The above excerpts represent Marja’s attempt to find a moral solution to the situation (not to discriminate but to keep the employee in the organization regardless of other employees who are prejudiced against her), but simultaneously illustrate her uncertainty about fully standing behind her moral values (Marja had not given the employee a permanent position, although there were possibilities to do so and no official reasons against it). We interpreted this approach as reflecting a moral identity moratorium. According to Marcia (2002), identity moratorium is characterized by being open-minded and thoughtful, continuing to examine alternatives, and trying to make identity-defining decisions for the future. Although we identified similar elements from Marja’s narrative, none of the interviewed leaders spoke of a clear, major exploration time regarding their moral values.

In addition, moral identity moratorium was identified in descriptions of previous states; brief periods of personal value exploration before making refined value commitments. This finding aligns with Marcia’s (2002) model, where, for most people, moratorium is a transitional state between two identity statuses initiated by disequilibrating circumstances. One such example comes from Anna, who described a period of active reflection and searching for different options regarding whether or not to employ a person with much absence due to illness:

I knew how much this person had been sick before. I guess that was the biggest ethical problem, because I shouldn’t have let that influence me: whether I hire that person or not. -- Another ethical issue was that I knew that this person was a challenging employee; I think it would’ve been immoral of me to move him/her to another unit. -- So I mapped different options, I called our lawyer, I contacted recruiting services, and I talked with my supervisor. And I talked a lot with this employee. (Anna)

The organizational context had a central role in allowing Anna to work through her identity moratorium. Norms related to a leader’s role in different fields of business were found to elicit moral conflicts in and of themselves. For example, Liisa spoke of how a value conflict initiated a disequilibrium phase for her, resulting in further values explorations (facilitating moral identity reconstruction):

Of course I understand that in this position [working as a chief customer officer in a private company] the business goals are really important. But then at the same time I find it really important to be just and keep the game fair and clean. And that became the challenge for me: these two goals started to compete with each other. (Liisa)

Whether or not a leader was able to analyze and resolve the controversies between competing value sets was used to define one’s current moral identity status. In Liisa’s case she chose to resign from her work after she realized the organization had unethical leaders who restricted her from acting according to her moral identity and central moral values:

The upper management clearly had their own circle of favorite employees. My own supervisor protected these people, and at the same time tried to influence me so that I would also favor them. The problem was that I always want to treat people fairly and equally. Finally, I just felt that I couldn’t stay in that situation anymore, where I had to be quiet, like I wouldn’t know anything about this [managers’ showing favor] that was going on around me. So I decided it was best that I resign. (Liisa).

Thus, she was able to find a solution which did not compromise her core values, although it meant leaving her job. In Anna’s case she was able to resolve her conflict related to hiring an employee:

I think that everyone deserves a chance, regardless of what the person’s history includes. That’s why I think I work in this field [in health care], and not somewhere in commercial business. I couldn’t have slept if I didn’t hire this person; I would have felt that I’ve really wronged her/him. I think you should always give new opportunities and see if people are capable of changing and developing. I believe that most employees have this will [to develop] in themselves. (Anna)

She described gaining even more confidence about her central values as a leader, treating employees with equality. In the citation she also refers to her line of work; how she felt that her values provided a better fit with working in health care where she could help people than in the profit-driven business sector. Both Liisa and Anna were able to find a way to act according to their personally meaningful and important moral values. In addition, although Marja represented a moratorium (state) regarding her current moral conflict, she also discussed her established value framework regarding her role as a moral leader. This approach, as we will describe next, depicts an achieved moral identity.

Moral Identity Achievement

In comparison to the foreclosed leaders, described earlier, another group of leaders were faced with similar external pressures and organizational demands. However, instead of accepting these demands without question, they elaborately described their own thinking processes, weighing different points of view, and in the end making decisions that were justifiable and in line with their own personal moral values. For example, Aino talked about how she saw her role in tackling a personnel crisis within her organization:

I think that it is my responsibility to take care of things, and I cannot be in conflict with myself. I know that these [employee conflicts] are unpleasant situations for the leader to handle, and you have to make difficult decisions regarding the employees. And people will be disappointed. But the way that I see my work is that I have to do what is right. (Aino)

In other words, these leaders were identified to have a ‘moral template’ that they applied to resolving different moral conflicts. They acknowledged contradictions between following various norms and regulations of their organizations and being flexible towards employees and customers as the diffused leaders did. However, leaders in this group described having a clear value framework which guided them in making decisions even when faced with competing demands. They did not try to avoid responsibility or unpleasant confrontations with their superiors or employees, but took actions that they saw as fair and that were aligned with their values, such as Aino described. We interpreted these leaders to have achieved moral identities.

According to Marcia’s (2002) definition, an achieved identity involves exploration of different perspectives and options before committing to one’s current value framework. In the context of moral conflicts, a similar status was identified among ten leaders, who talked about high moral value coherence based on personal reflection:

I have three simple questions that I follow when I make decisions. First, is it safe? Second, is it right? I mean morally right, not right by the formal guidelines. And third, is it fair? If I can answer ’yes’ to all these questions and act accordingly, even if I end up breaking some rule, I cannot be badly judged because I had good intentions. I think it is my duty as a leader to help the employees so that they can perform their best in their work. Even though I legally represent my employer, I will still take my employees’ side. (Mika)

Above, Mika describes how he had found a personal moral template that helped him to make moral decisions according to his own core values (safety, justice, and equality) and to justify his actions even though they could sometimes mean taking a risk to act against a formal workplace rule.

However, firm commitments to personally developed moral values can sometimes be difficult adapt to the organizational structure. Some of the achieved leaders described basing decisions on their personal values, even if it meant contradicting an official guideline (as in Mika’s citation above). For example, Pirkko chose to prioritize the best interests of the customer families which she saw as the core value in her work at a day care center, instead of following the formal rules:

In a way, I was doing the wrong thing [by giving the parent flexible options to choose how their child’s day care would be arranged], because it was against the board’s decision. It was against the policies that the board, supervisors, and the head of services had outlined. -- But I thought that I will make this decision, take the responsibility for it. Because I think that the main aim of our work [in daycare] is to think about what is best for the children and to support families’ well-being. They are always my main concerns. I saw that if the parent gets the time for day care they hoped for, the parent is able to attend therapy. And that is in the best interest of the child. (Pirkko)

In these situations the leaders acknowledged the role of the context (different norms and practical rules that are set by the organization), but the decision that they made represented the most moral solution according to their own values. For example, if they saw that the orders were harmful to their employees or customers (as in Pirkko’s case above), they prioritized the decision that was aligned with their own moral values instead of adhering to formal guidelines. This approach depicts a careful consideration process, where multiple competing values are evaluated and prioritized. To understand how leaders attained this moral identity status, we next discuss the developmental processes in more detail.

Processes Related to Moral Identity Development

We found that a cyclical, iterative process was evident in the moral identity domain, as moral identity reconsideration and reconstruction of previous value commitments may be generated in the course of addressing a moral conflict. As we investigated the context-specific characteristics of these processes (how they appear in the moral domain within organizations), we found retrospective accounts of different personal processes related to moral identity development. Pirkko provides an example:

I think I was quite knowledgeable [when I was younger]. I mean, I used to be very sure about how things are or how they should be. Of course, I can still sometimes make quick decisions when I have to, but I think I was previously much more black and white, quickly saying and letting others understand that I know everything. (Pirkko)

Above, Pirkko describes how she used to be more rigid and certain in her knowledge, whereas currently she sees the complexity of moral issues and tries to take a broader view when making moral decisions:

I’ve learned to look at situations more broadly. I don’t make simple and straightforward decisions anymore. I’ve really learned how to think things through and consider my options by looking at the whole. (Pirkko)

The narratives by the achieved leaders suggest that experiences that broaden the leaders’ viewpoints may trigger values exploration and potentially bring confidence and consistency to their decision-making processes—if the exploration leads to self-chosen value commitments. Pirkko described this process in the following way:

I’ve gained more life experience, work experience, and I have constantly studied more. …It opens up different worlds and viewpoints; you don’t live in a bubble anymore or look through rosy glasses. I try to understand that we are all different. (Pirkko)

Thus, experiences can act as facilitators for moral identity reconstruction, but this process needs to include some form of personal self-reflection. Leaders also indicated that having previous role models—good or bad, ethical or unethical—had influenced their current achieved moral identity:

I have had one really bad supervisor in my history. It was a meaningful and useful experience to me; the supervisor was so bad that it became good. Good in the sense that I learned I want to be different, I want to be good towards my employees. It is my responsibility to take care of them. (Minna)

Thus, either following the good examples the leaders had witnessed from other supervisors or choosing to act contrary to the bad examples they had seen had affected their actions as a moral leader. In contrast, a lack of experience, such as being a new member of the work community or not having previous experience of being in a leadership position, can make the leader more susceptible to external pressures. Mika described one such example as follows:

I was under 25, working as a leader in summer camp. I had no leadership experience at that time and I was quite clueless when facing the conflict [how to deal with a janitor who was intoxicated in the camp with under-aged children present]. -- The pressure and opinions from the personnel were strong towards intervening forcefully to the situation [to remove the employee immediately from the camp]. Now, with this life experience I don’t think that their opinions would have affected my choices as much as they did then. Back then I was younger and more black and white with my options. That this is how it goes, you are drunk, and you cannot be drunk in a camp with children, it is not right. Now I think that maybe there could be a different option, to intervene so that the person can save their face and keep their dignity.” (Mika)

As discussed previously, Mika currently described following his own moral framework with three central questions related to his core values (is it safe, just, and equal). Thus, he described a significant development in his moral views from accepting and obeying external expectations (how the conflict should be handled) to following a personally developed, more flexible set of moral guidelines.

Discussion

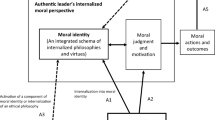

Our study highlighted important characteristics of moral identity emergence and development in moral conflicts among leaders within organizations. We have summarized our main findings from present data in Fig. 1, which illustrates how leaders’ moral identities can become more coherent and mature over time as a function of personal identity processes and the contexts in which they occur.

Moral identity can represent a relatively unchanging condition (moral identity viewed as a trait; the x-axis in Fig. 1) that affects person–context interactions; the ways individuals approach moral conflicts. Moral diffusion as a trait described leaders who lacked a personal moral framework. They experienced moral challenges as constant, stressful, and ruminative considerations of justifications for their everyday decisions. These decisions depended strongly on situational influences, thus leaving them more susceptible to external pressures. Leaders who were identified with trait foreclosure avoided personal responsibility by narrowing or simplifying the rationale for their decisions. They chose their options for moral actions based on what was available from the context (for example, justifying them as being according to a given rule by the company). Thus, they were also susceptible to external expectations and pressures because of the personal difficulty of detaching from or critically reviewing the values and rules imposed by the organization.

Achieved moral identity as a trait was assigned to leaders who had selected and committed to their personal values, which they worked to integrate with organizational values, resulting in a coherent yet flexible moral framework. They recognized different factors which had helped them to build their moral identity, such as reflecting on their previous life and work experience or having previous leaders who had acted as ethical role models. These experiences had increased their confidence and broadened their perspectives. This kind of self-reflexivity has been suggested to be a central personal factor for moral identity (Weaver 2006), which received empirical support from our findings. A moral identity moratorium was represented by a period of active value reflection, although it was not identified as a long-term trait-like status in our study. This depiction is in line with Marcia’s (2002) theory, according to which an identity moratorium is more likely to be only a short-term developmental period; it is simply too uncomfortable to remain in this explorative phase for long.

Temporary statuses through which the individual passes as a part of a developmental process represent moral identity as a state (the y-axis in Fig. 1). If one faces a moral conflict that cannot be resolved from within one’s current framework of moral values, one may revise these values. This process may lead to changes in commitments, and eventually, moral identity reformulation. The notion that conflict can trigger identity change is a feature of many general identity studies (e.g., Bosma and Kunnen 2001), and movement from one identity status to another has been associated with a disequilibrating event (Marcia 2002). When significant life challenges are difficult to address by only employing one’s earlier values and identity commitments, a developmental change may occur. We found similar cyclical processes within the moral domain, which are depicted by the flow of arrows in Fig. 1. The increasing size of the circles illustrates increasing coherence and breadth of moral identity commitments. One’s level of moral maturity depends on the range of personal life experiences and personal reflections over these experiences, at least that the leaders in this study presented. Thus, in line with what has been suggested previously (Krettenauer and Hertz 2015; Krettenauer et al. 2016), moral identity development is not simply a linear function of age. Longitudinal studies could provide more detailed evidence of these developmental cycles in moral identity by considering whether the moral identity statuses are more often short-term phases or relatively permanent traits during adulthood.

Whether or not an individual experiences moral conflict as an identity-disequilibrating event that triggers moral identity development depends on one’s moral identity status at the “outset.” There can be at least two types of resistance towards self-reflection that prevents personal development, illustrated in Fig. 1 as an arrow leading away from the cycles. From our data, leaders with diffused moral identities were resistant to identity disequilibration because they appeared to lack any moral values identity framework in the first place. In addition, leaders with foreclosed moral identities of this study were unlikely to reconstruct their moral identities, because their identity was built on rigid commitments coupled with a reluctance to explore new alternative values. Individuals reflecting these two moral identity statuses would therefore likely need strong assistance and support in recognizing and considering the moral aspects both within their surroundings (potential moral conflicts at work) and within themselves (personal values). We discuss these possibilities in more detail in a subsequent section on practical applications.

Theoretical Contributions

Our findings enable a broader understanding of the differences in moral identity among individuals—whereby moral identity is not conceptualized merely as a continuum, ranging from high to low moral identity centrality and symbolization (Aquino and Reed 2001), but as a more complex interaction between the processes of moral values commitment and exploration that occur within organizational context. This contributes to understanding how moral identity manifests itself among working adults in organizations, an issue which has gained surprisingly little research attention in the recent past (Jennings et al. 2015). Based on our findings, we concur with Jennings et al. (2015) in arguing that studies using student samples or scenario studies alone are not sufficient, as they are likely to simplify the ambiguities, conflicting viewpoints, and complexities of actual work-related moral conflicts. Rather, future studies could move towards examining moral identity processes among diverse adult leader samples and in different work contexts in more detail. For example, what kinds of within-person differences can be identified when people face a range of different moral questions? Is it possible that an individual might approach a certain type of moral conflict with a more normative frame (foreclosure), whereas more complex or intensive moral dilemmas could activate a different moral identity decision-making style (e.g., being more flexible and open to available information, as in the achieved moral identity)? These situational differences could be investigated, for example, by applying Berzonsky’s (1989) concept of identity styles to the moral domain. Berzonsky’s approach is an extension of Marcia’s identity status model, and it uses a social cognitive perspective to address how individuals process problematic situations—whether they focus on relevant information (similar to the achieved identity status), on the normative expectations of others (similar to the foreclosed identity status), or on avoiding the issue altogether (similar to the diffused status). Thus, although the different Berzonsky identity styles are related to identity statuses, they are not seen as a sequence of stages, but as different forms of personal information-processing styles.

Our study both supported Marcia’s original identity model (2002) and extended it to the moral domain with some important considerations especially in the business ethics context. Namely, individuals representing the various moral identity statuses interacted with the moral conflicts they faced and with their organizational contexts in different ways, some being more susceptible to contextual influences than others (as theorized by Weaver 2006). Individuals foreclosed in moral identity uncritically adapted their behaviors to the organization’s norms and values. This approach becomes problematic if the leader is working in a less-than-ethical organization or under high pressure in rapidly changing business environments. These conditions can increase the risk of unethical behaviors among leaders working within such contexts. In comparison, having an achieved moral identity can help leaders to act according to their personal moral values even when being pressured externally with conflicting demands or even unethical expectations. Such leaders are more likely to feel confident in following their own moral value framework to which they have committed following personal exploration. These person–context interactions should be acknowledged in future studies of moral identity. It may be that particular types of organizational climates or cultures are associated with specific moral identity statuses. For example, hierarchical and authoritarian organizations may socialize their members to adopt a foreclosed moral identity by reinforcing obedience to rules and norms. Or individuals with foreclosed moral identities might seek these types of organizations as they find a good person-organization value fit in them.

Practical Contributions

From a practical perspective, supporting managers to become moral leaders should begin by recognizing their current moral identity framework, from which they are making decisions and acting. To encourage moral leader development, supervisors need to support individuals in finding personally meaningful moral convictions through moral values exploration and commitment. To enable this kind of support, a supervisor himself or herself should not be threatened by the consideration of an alternative set of moral values that may challenge the prevailing rules or practices of the organization. Additionally, insights from previous identity research (see Ferrer-Wreder and Kroger 2020, pp. 46–48) might be applied to differentially support those adopting the various moral identity statuses. Leaders with diffused moral identities need support in becoming more conscious of moral issues, of finding and strengthening their own values, and help in accepting their role of responsibility in conflicting situations. This intervention could include ethics training within the organization in order to increase moral sensitivity (Ritter 2006).

For individuals with foreclosed moral identities, the challenge is to promote more flexible considerations of alternative views. Any attempts to change their rigid views should be done slowly in a safe environment by providing new role models and alternatives (Ferrer-Wreder and Kroger 2020). One practical approach might be to include foreclosed leaders in teams, where sharing the responsibility with colleagues might encourage them to consider various perspectives for moral decision-making. Individuals who are going through a moral identity moratorium are likely to benefit from a positive role model (a supervisor, colleague, or some other kind of a mentor) who could help by reflecting the leader’s own conflicting moral identity values in a supportive manner and thus facilitate identity resolution. Achieved moral identities should be provided continuous opportunities to develop their moral value insights, such as increasing moral competence and acknowledging personal strengths of character (see, e.g., the Values in Action tool that could be applied among adults; Park and Peterson 2006).

To summarize, organizations should recognize that rewarding their leaders only for loyalty and obedience to established policy and norms limits the potential both of that individual as well as the organization. The contemporary business world is rife with ambiguous and multifaceted problems, and business organizations should encourage discussion of various uncertainties, potential negative effects of certain decisions, and alternative points of view. Increasing such discussions and individual approaches towards moral conflicts can have the potential to act as a driver for moral identity reformulation cycles, eventually enabling a leader’s moral identity to become richer, more nuanced, and coherent and thus best contribute to the future of the organization; such discussions may also decrease the risks of immoral actions within the organization.

Limitations

There are certain limitations that should be considered when generalizing our findings. First is the problem of the potential selectiveness of the sample; leaders who were willing to participate in the interview may have had heightened interest in moral identity issues. However, regardless of the study recruiting method (inviting voluntary participants) and the CIT method that predisposed the participants to reflect on moral issues, we were able to identify different ways of approaching moral conflicts among these leaders—even diffused leaders without a clear set of moral values. Thus, although we used a relatively small convenience sample, it did provide evidence of different moral identity statuses among leaders.

Second, as we chose to use a qualitative design, the relatively small sample size may not generalize to all groups of leaders. It is also possible that by utilizing a larger sample we might have obtained more leaders in moral identity moratorium and learned more about the different moral conflicts and moral identity processes found in this group. In the current study, this status was identifiable only from the narratives of three leaders. However, the moratorium status is by definition harder to detect, as it represents a temporary period of values exploration, not usually a long-term state.

Third, the leaders in this study were prompted to describe only one moral conflict in the interview and we did not focus on the moral intensity of the conflicts that the leaders described. Future studies should account for potential interactions between different conflicts, their moral intensity, and the identity-related responses. For example, when intense, moral questions involving personnel are present, more leaders might be uncertain in their moral decisions as they try to find resolutions (i.e., in a moratorium state), because there can be high proximity (e.g., closeness of the employee) and clear consequences (e.g., an employee will lose their job) that could result from the leader’s decision (see Jones 1991). However, the participants received the interview questions before the interview and thus had time to select a moral conflict that was personally meaningful to them and that they felt comfortable in sharing. It is also worth noting that even from this starting point, some of the participants could not describe a clear disequilibrating event. This finding suggested that some individuals struggled to identify a specific conflict that challenged their moral value frame.

Conclusions

Leaders should be able to expose themselves to and engage in moral issues, because moral dilemmas are likely to be present at the core of organizational leadership positions. The overall maturity of a leader’s moral identity results from a combination of personal exploration and commitment to moral values—a balance between coherent and reflexive personal moral values which are applied flexibly in order to reach moral resolutions to work conflicts. To construct this kind of a mature moral identity requires the capacity for both self-reflection and the critical examination of established social and organizational orders. Being able to outline what values are important to oneself and acting according to those personally meaningful moral guidelines defines an achieved moral identity—a key dimension of being a moral leader.

References

Aquino, K., & Reed, A., II. (2002). The self-importance of moral identity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83(6), 1423–1440.

Ashforth, B. E., & Schinoff, B. S. (2016). Identity under construction: How individuals come to define themselves in organizations. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 3, 111–137.

Berg, B. L., & Lune, H. (2012). Qualitative research methods for the social sciences. Boston: Pearson.

Berzonsky, M. D. (1989). Identity style: Conceptualization and measurement. Journal of Adolescent Research, 4(3), 268–282.

Blasi, A. (1995). Moral understanding and the moral personality: The process of moral integration. In W. M. Kurtines & J. L. Gewirtz (Eds.), Moral development: An introduction (pp. 229–253). Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Bosma, H. A., & Kunnen, E. S. (2001). Determinants and mechanisms in ego identity development: A review and synthesis. Developmental Review, 21(1), 39–66.

Brown, A. D. (2015). Identities and identity work in organizations. International Journal of Management Reviews, 17(1), 20–40.

Brown, M. E., & Treviño, L. K. (2006). Ethical leadership: A review and future directions. The Leadership Quarterly, 17(6), 595–616.

Brown, M. E., & Treviño, L. K. (2014). Do role models matter? An investigation of role modeling as an antecedent of perceived ethical leadership. Journal of Business Ethics, 122(4), 587–598.

Butterfield, L. D., Borgen, W. A., Amundson, N. E., & Maglio, A. S. T. (2005). Fifty years of the critical incident technique: 1954–2004 And beyond. Qualitative Research, 5(4), 475–497.

Butterfield, K. D., Treviño, L. K., & Ball, G. A. (1996). Punishment from the manager’s perspective: A grounded investigation and inductive model. Academy of Management Journal, 39(6), 1479–1512.

Day, D. V., & Harrison, M. M. (2007). A multilevel, identity-based approach to leadership development. Human Resource Management Review, 17(4), 360–373.

Detert, J. R., Treviño, L. K., & Sweitzer, V. L. (2008). Moral disengagement in ethical decision making: A study of antecedents and outcomes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(2), 374–391.

Elo, S., & Kyngäs, H. (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62(1), 107–115.

Erikson, E. H. (1964). Insight and responsibility. New York: Norton.

Ferrer-Wreder, L., & Kroger, J. (2020). Identity in adolescence: The balance between self and other. New York: Routledge.

Gioia, D. A., & Sims, H. P., Jr. (1986). Cognition-behavior connections: Attribution and verbal behavior in leader–subordinate interactions. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 37(2), 197–229.

Greenbaum, R. L., Mawritz, M. B., Mayer, D. M., & Priesemuth, M. (2013). To act out, to withdraw, or to constructively resist? Employee reactions to supervisor abuse of customers and the moderating role of employee moral identity. Human Relations, 66(7), 925–950.

Gremler, D. D. (2016). The critical incident technique in service research. Journal of Service Research, 7(1), 65–89.

Hardy, S., & Carlo, G. (2011a). Moral identity. In S. J. Schwartz, K. Luyckx, & V. Vignoles (Eds.), Handbook of identity theory and research (Vol. 2, pp. 495–513). New York: Springer.

Hardy, S. A., & Carlo, G. (2011b). Moral identity: What is it, how does it develop, and is it linked to moral action? Child Development Perspectives, 5(3), 212–218.

Hardy, S. A., & Carlo, G. (2005). Identity as a source of moral motivation. Human Development, 48(4), 232–256.

Jennings, P. L., Mitchell, M. S., & Hannah, S. T. (2015). The moral self: A review and integration of the literature. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 36, S104–S168.

Jones, T. M. (1991). Ethical decision making by individuals in organizations: An issue-contingent model. Academy of Management Review, 16(2), 366–395.

Krettenauer, T., Murua, L. A., & Jia, F. (2016). Age-related differences in moral identity across adulthood. Developmental Psychology, 52(6), 972–984.

Kroger, J., & Marcia, J. E. (2011). The identity statuses: Origins, meanings, and interpretations. In S. J. Schwartz, K. Luyckx, & V. L. Vignoles (Eds.), Handbook of identity theory and research (Vol. 2, pp. 31–53). New York: Springer.

Kroger, J., & Marcia, J. E. (2020). Erikson, the identity statuses and beyond. In C. Demuth, M. Watzlawik, & M. Bamberg (Eds.) Cambridge handbook of identity. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Lapsley, D., & Hardy, S. A. (2017). Identity formation and moral development in emerging adulthood. In L. M. Padilla-Walker & L. J. Nelson (Eds.), Flourishing in emerging adulthood: Positive development during the third decade of life (pp. 14–39). New York: Oxford University Press.

MacIntyre, A. (1999). Social structures and their threats to moral agency. Philosophy, 74(3), 311–329.

Marcia, J. E. (1966). Development and validation of ego-identity status. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 3, 551–558.

Marcia, J. E. (2002). Identity and psychosocial development in adulthood. Identity: An International Journal of Theory and Research, 2(1), 7–28.

Marcia, J. E. (2007). Theory and measure: The identity status interview. In M. Watzlawik & A. Born (Eds.), Capturing identity: Quantitative and qualitative methods (pp. 1–14). Lanham, MD: University Press of America.

Mayer, D. M., Aquino, K., Greenbaum, R. L., & Kuenzi, M. (2012). Who displays ethical leadership, and why does it matter? An examination of antecedents and consequences of ethical leadership. Academy of Management Journal, 55(1), 151–171.

Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Nielsen, R. P. (2006). Introduction to the special issue. In search of organizational virtue: Moral agency in organizations. Organization Studies, 27(3), 317–321.

Park, N., & Peterson, C. (2006). Moral competence and character strengths among adolescents: The development and validation of the Values in Action Inventory of Strengths for Youth. Journal of Adolescence, 29(6), 891–909.

Ritter, B. A. (2006). Can business ethics be trained? A study of the ethical decision-making process in business students. Journal of Business Ethics, 68(2), 153–164.

Schwartz, S. J. (2001). The evolution of Eriksonian and neo-Eriksonian identity theory and research: A review and integration. Identity: An International Journal of Theory and Research, 1(1), 7–58.

Shao, R., Aquino, K., & Freeman, D. (2008). Beyond moral reasoning: A review of moral identity research and its implications for business ethics. Business Ethics Quarterly, 18(4), 513–540.

Skarlicki, D. P., & Rupp, D. E. (2010). Dual processing and organizational justice: The role of rational versus experiential processing in third-party reactions to workplace mistreatment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95(5), 944–952.

Skubinn, R., & Herzog, L. (2016). Internalized moral identity in ethical leadership. Journal of Business Ethics, 133(2), 249–260.

Smircich, L., & Morgan, G. (1982). Leadership: The management of meaning. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 18(3), 257–273.

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of qualitative research: Procedures and techniques for developing grounded theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Watson, T. J. (2008). Managing identity: Identity work, personal predicaments and structural circumstances. Organization, 15(1), 121–143.

Weaver, G. R. (2006). Virtue in organizations: Moral identity as a foundation for moral agency. Organization Studies, 27(3), 341–368.

Wilcox, T. (2012). Human resource management in a compartmentalized world: Whither moral agency? Journal of Business Ethics, 111(1), 85–96.

Zhu, W., Treviño, L. K., & Zheng, X. (2016). Ethical leaders and their followers: The transmission of moral identity and moral attentiveness. Business Ethics Quarterly, 26(1), 95–115.

Acknowledgements

Open access funding provided by University of Jyväskylä (JYU).

Funding

This study was funded by the Academy of Finland (Grant Number 294428).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the Ethical Standards of the Institutional and/or National Research Committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Huhtala, M., Fadjukoff, P. & Kroger, J. Managers as Moral Leaders: Moral Identity Processes in the Context of Work. J Bus Ethics 172, 639–652 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-020-04500-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-020-04500-w