Abstract

The introduction of new medical treatments based on invasive technologies has often been surrounded by both hopes and fears. Hope, since a new intervention can create new opportunities either in terms of providing a cure for the disease or impairment at hand; or as alleviation of symptoms. Fear, since an invasive treatment involving implanting a medical device can result in unknown complications such as hardware failure and undesirable medical consequences. However, hopes and fears may also arise due to the cultural embeddedness of technology, where a therapy due to ethical, social, political and religious concerns could be perceived as either a blessing or a threat. While Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS) for treatment resistant depression (TRD) is still in its cradle, it is important to be proactive and try to scrutinize both surfacing hopes and fears. Patients will not benefit if a promising treatment is banned or avoided due to unfounded fears, nor will they benefit if DBS is used without scrutinizing the arguments which call for caution. Hence blind optimism is equally troublesome. We suggest that specificity, both in terms of a detailed account of relevant scientific concerns as well as ethical considerations, could be a way to analyse expressed concerns regarding DBS for TRD. This approach is particularly fruitful when applied to hopes and fears evoked by DBS for TRD, since it can reveal if our comprehension of DBS for TRD suffer from various biases which may remain unnoticed at first glance. We suggest that such biases exist, albeit a further analysis is needed to explore this issue in full.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The approval was a humanitarian device exemption.

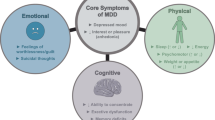

This is one of the clinical diagnoses of depression, sometimes referred to as recurrent depressive disorder, clinical depression, major depression, and unipolar depression. Whenever “depression” is mentioned in the paper, this refers to MDD unless something else is specified.

The expression “treatment-refractory depression” refers to depressions where standard therapies have failed. However, there seems to be no agreement on how many treatment strategies that are necessary, neither regarding for instance the number of antidepressant drugs used, nor whether electroconvulsive therapy is mandatory, before the depression is considered to be treatment-refractory; an important constraint to keep in mind when the expression is employed. Further, though both unipolar and bipolar depressions can be treatment-refractory, it is the former that is presupposed throughout the text.

General claims about depression require some caution: The etiology of depression is debated as is whether it is a disease, a disorder or, as has been claimed by for instance the anti-psychiatry movement, a social construct; neither is the neurobiological mechanisms fully understood, and there have been suggestions that depression may in fact be more than one disease considering variance in symptoms, response to therapy, comorbidities etc.; the diagnosis is based on assessment tests performed by the patient and physician, allowing for individual variances as well as for instance cultural differences; it has been estimated that a substantial share of those suffering from depression never get spotted since they refrain from seeking health care etc. The following section should be read with these limitations kept in mind.

Though these results are ambiguous; it is still not clear whether it is the depression that causes the brain damage or vice versa, alternatively there could be an unknown factor causing both the depression and the cell death. This ambiguity also applies to other examples of cell death throughout the text.

Even in a country as Sweden, with a population of only nine million people, the economic burden of depression, including both direct and indirect costs, is high and keeps increasing. In 1997 the cost of depression was €1.7 billion, while in 2005 it had increased to €3.5 billion.

The quote obtained from Stone 2001.

Response was defined as a 50% reduction in the 17 item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD-17) score from the pre-treatment baseline, whereas remission was defined as a HDRS-17 score of 7 or less. Both measures were made after a 6 month follow-up period.

From the 1950s onward experiments were conducted where rudimentary electrodes stimulated the brain to treat psychiatric disorders, such as the Tulane Electrical Brain Stimulation Program, conducted by Robert Heath, and the experiments conducted by José Delgado at Yale University. However, since these early experiments do not live up to the standard of todays rigorous research protocols, they are not listed in the main text.

The six patients from Mayberg’s study were included in this study. Response and remission were defined as stated in the previously mentioned study.

Response was defined as a 50% reduction in the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS28) score from the pre-treatment baseline, whereas remission was defined as a HDRS28 score of less than 10.

To make this comparison more comprehensive, some features are mentioned which strictly speaking are concerns of nonmaleficence.

Vagus nerve stimulation got a Food and Drug Administration approval for TRD in 2005.

The number of procedures are somewhat deceptive since the limbic leucotomy is nothing but a combination of the cingulotomy and the stereotactic subcaudate tractotomy.

Though these enhancements, if real and not due to other explanations such an inadequate assessing tools, are side effect of the stimulation such anecdotal reports have opened up for the question if DBS in the future could, and will, be used not only for treatment but for augmenting the function of normally functioning brains.

For instance, is the patient really treatment-refractor?

A proposed hypothesis is that the electrical stimulation inhibits the effected structures neuronal activity, while another—more recent—suggestion is that the reduction of disease symptoms is due to a disruption of the transmission of pathologic bursting and oscillatory activity created by a change in the stimulated nucleus’s firing pattern. The nucleus firing pattern adapts to the DBS pulse train, thus creating a more regular bursting, which supposedly blocks the above mentioned pattern of abnormal neural activity.

Such studies are now underway both in Europe and America, but we have yet to await the results.

Such studies can be achieved without sham surgery even if all patients receive a neurostimulator as long as some implants are activated whilst others are not, where on and off periods is reversed during the duration of the study. With this design, neither the patient nor the evaluating physician knows which implant is activated [34]. However, it has been claimed that many patients can feel when their neurostimulators are on, hence making a double-blinded study impossible, which in turn would limit the scientific value of the results [40].

This has also been pointed out by Bell et al.

Safe should not be understood as that there are no risks of harm involved in ECT, there are. Temporary memory losses are common, and in rare cases these memory losses are permanent. However, ECT remains an underutilized therapy considering the vast empirical evidence supporting its employment.

References

ten Have, H. 1995. Medical technology assessment and ethics. The Hastings Center Report 25(5): 13–20.

Hofmann, B., J.H. Solbakk, and S. Holm. 2006. Teaching old dogs new tricks: the role of analogies in bioethical analysis and argumentation concerning new technologies. Theoretical Medicine and Bioethics 27: 397–413.

Vos, R., and D.L. Willems. 2000. Technology in medicine: ontology, epistemology, ethics and social philosophy at the crossroads. Theoretical Medicine and Bioethics 21(1): 1–7.

Medtronics. http://www.medtronic.se/sjukdom/tvaangssyndrom/produkt/faq/index.htm. Accessed 2011.

FDA, US. 2009. Approval order: Reclaim™ DBS™ Therapy for OCD - H050003.

Talan, J. 2009. Deep brain stimulation: a new treatment shows promise in the most difficult cases. New York: Dana.

Foundation, Dana. 2008. Mind and matter ethical challenges of deep brain stimulation—Edited Transcript.

Mauskopf, J.A., G.E. Simon, A. Kalsekar, C. Nimsch, E. Dunayevich, and A. Cameron. 2009. Nonresponse, partial response, and failure to achieve remission: humanistic and cost burden in major depressive disorder. Depression and Anxiety 26(1): 83–97. doi:10.1002/da.20505.

Sobocki, P., I. Lekander, F. Borgstrom, O. Strom, and B. Runeson. 2007. The economic burden of depression in Sweden from 1997 to 2005. European Psychiatry 22(3): 146–152. doi:10.1016/j.eurpsy.2006.10.006.

Fins, J.J. 2004. Neuromodulation, free will and determinism: lessons from the psychosurgery debate. Clinical Neuroscience Research 4(1–2): 113–118.

Heller, A., A. Amar, C. Liu, and M. Apuzzo. 2006. Surgery of the mind and mood: A mosaic of issues in time and evolution. Neurosurgery 59(4): 720–739.

Kopell, B.H., and B.D. Greenberg. 2008. Anatomy and physiology of the basal ganglia: Implications for DBS in psychiatry. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews 32(3): 408–422.

Rabins, P., S. Appleby Brian, R. Jason Brandt, B. DeLong Mahlon, D. Laura, D. Loes Gabriels, G. Benjamin, et al. 2009. Scientific and Ethical Issues Related to Deep Brain Stimulation for Disorders of Mood, Behavior, and Thought. Archives of General Psychiatry 66(9): 931–937.

Bell, E., G. Mathieu, and E. Racine. 2009. Preparing the ethical future of deep brain stimulation. Surgical Neurology 72(6): 577–586.

Agren, H. 1998. To trim the soul. Does brain surgery belong in psychiatry? Läkartidningen 95(45): 4948–4949.

The New York Times. 1937. Surgery used on the soul-sick; relief of obsessions is reported. June 7.

Delgado, José. 1969. Physical control of the mind: Toward a psychocivilized society.

Hansson, S.O. 2005. Implant ethics. Journal of Medical Ethics 31(9): 519–525. doi:10.1136/jme.2004.009803.

Mark, Vernon H., and Frank R. Ervin. 1970. Violence and the brain. [1st Aufl. New York,: Medical Dept.

McGee, E.M., and G.Q. Maguire. 2007. Becoming Borg to become immortal: regulating brain implant technologies. Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics 16(3): 291–302.

Nordmann, A. 2008. Ignorance at the heart of science? Incredible narratives on brain-machine interfaces. In Nanobiotechnology, nanomedicine and human enhancement, ed. S.J. Ach and B. Lüttenberg, 113–132. Berlin: Lit Verlag.

Ford, P.J. 2007. Neurosurgical implants: clinical protocol considerations. Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics 16(3): 308–311.

Kuhn, Jens, Wolfgang Gaebel, Joachim Klosterkoetter, and Christiane Woopen. 2009. Deep brain stimulation as a new therapeutic approach in therapy-resistant mental disorders: ethical aspects of investigational treatment.

Synofzik, M., and T.E. Schlaepfer. 2008. Stimulating personality: ethical criteria for deep brain stimulation in psychiatric patients and for enhancement purposes. Biotechnology Journal 3(12): 1511–1520. doi:10.1002/biot.200800187.

Krishnan, V., and E.J. Nestler. 2008. The molecular neurobiology of depression. Nature 455(7215): 894–902. doi:10.1038/Nature07455.

Organization, World Health. 2003. The World Health Report 2003: Shaping the Future.

Mathers, Colin D. 2006. Projections of Global Mortality and Burden of Disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS medicine.

Organization, World Health. 2001. The world health report 2001—Mental Health: New Understanding, New Hope

ten Doesschate, Mascha C., Maarten W. J. Koeter, and Claudi L. H. Bockting. 2010. Health related quality of life in recurrent depression: a comparison with a general population sample. 120:126–133.

Posternak, M.A., and I. Miller. 2001. Untreated short-term course of major depression: a meta-analysis of outcomes from studies using wait-list control groups. Journal of Affective Disorders 66(2–3): 139–146. doi:S0165032700003049.

SBU, Statens beredning för medicinsk utvärdering. 2004. Behandling av depressionssjukdomar, volym 1–3. Stockholm: En systematisk litteraturöversikt.

Lozano, A.M., H.S. Mayberg, P. Giacobbe, C. Hamani, R.C. Craddock, and S.H. Kennedy. 2008. Subcallosal cingulate gyrus deep brain stimulation for treatment-resistant depression. Biological Psychiatry 64(6): 461–467.

Shields, D.C., W. Asaad, E.N. Eskandar, F.A. Jain, G.R. Cosgrove, A.W. Flaherty, E.H. Cassem, B.H. Price, S.L. Rauch, and D.D. Dougherty. 2008. Prospective assessment of stereotactic ablative surgery for intractable major depression. Biological Psychiatry 64(6): 449–454.

Schwalb, J.M., and C. Hamani. 2008. The history and future of deep brain stimulation. Neurotherapeutics 5(1): 3–13.

Malhi, G.S., and J.R. Bartlett. 2000. Depression: a role for neurosurgery? British Journal of Neurosurgery 14(5): 415–422.

Kramer, P.D. 2005. Against depression. New York: Viking.

Ford, P.J., and J.M. Henderson. 2006. Functional neurosurgical intervention: neuroethics in the operating room. In Neuroethics: Defining the issues in theory, practice, and policy, ed. Illes. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ford Paul, J. 2009. Vulnerable brains: research ethics and neurosurgical patients. The Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics 37(1): 73–82.

Fins, J.J. 2009. Deep brain stimulation, deontology and duty: the moral obligation of non-abandonment at the neural interface. Journal of Neural Engineering 6(5): 050201. doi:10.1088/1741-2552/6/5/050201.

Larson, P.S. 2008. Deep brain stimulation for psychiatric disorders. Neurotherapeutics 5(1): 50–58. doi:10.1016/j.nurt.2007.11.006.

Glannon, W. 2008. Deep-brain stimulation for depression. HEC Forum 20(4): 325–336.

Johansson, V. 2009. Do brain-machine interfaces on nano scale pose new ethical challenges? In Size matters: Ethical, legal and social aspects of nanobiotechnology and nano-medicine, ed. J. Ach and C. Weidemann, 75–99. Münster: LIT Verlag.

Clausen, J. Ethical brain stimulation—neuroethics of deep brain stimulation in research and clinical practice. European Journal of Neuroscience 32(7):1152–1162. doi:10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07421.x.

Johnson, M.D., S. Miocinovic, C.C. McIntyre, and J.L. Vitek. 2008. Mechanisms and targets of deep brain stimulation in movement disorders. Neurotherapeutics 5(2): 294–308. doi:10.1016/j.nurt.2008.01.010.

Stone, J.L. 2001. Dr. Gottlieb Burckhardt—the pioneer of psychosurgery. Journal of the History of the Neurosciences 10(1): 79–93.

Kopell, B.H., and B. Greenberg. 2004. Psychiatric neurosurgery: Trials, tribulations–and promise. Behavioral Health Management 24(3): 14–18.

Mayberg, H.S., A.M. Lozano, V. Voon, H.E. McNeely, D. Seminowicz, C. Hamani, J.M. Schwalb, and S.H. Kennedy. 2005. Deep brain stimulation for treatment-resistant depression. Neuron 45(5): 651–660. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2005.02.014.

Aouizerate, B., C. Martin-Guehl, E. Cuny, D. Guehl, H. Amieva, A. Benazzouz, C. Fabrigoule, B. Bioulac, J. Tignol, and P. Burbaud. 2005. Deep brain stimulation for OCD and major depression. The American Journal of Psychiatry 162(11): 2192. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.162.11.2192.

Bewernick, B.H., R. Hurlemann, and A. Matusch. 2010. Nucleus accumbens deep brain stimulation decreases ratings of depression and anxiety in treatment-resistant depression. Biological Psychiatry 67(2): 110–117.

Jimenez, F., F. Velasco, R. Salin-Pascual, J.A. Hernandez, M. Velasco, J.L. Criales, and H. Nicolini. 2005. A patient with a resistant major depression disorder treated with deep brain stimulation in the inferior thalamic peduncle. Neurosurgery 57(3): 585–593. doi:00006123-200509000-00027. discussion 585–593.

Kuhn, J., D. Lenartz, W. Huff, S. Lee, A. Koulousakis, J. Klosterkoetter, and V. Sturm. 2007. Remission of alcohol dependency following deep brain stimulation of the nucleus accumbens: valuable therapeutic implications? Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry 78(10): 1152–1153. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2006.113092.

Malone, D.A., D.D. Dougherty, and A.R. Rezai. 2009. Deep brain stimulation of the ventral capsule/ventral striatum for treatment-resistant depression. Biological Psychiatry 65(4): 267–276.

Neimat, J.S., C. Hamani, P. Giacobbe, H. Merskey, S.H. Kennedy, H.S. Mayberg, and A.M. Lozano. 2008. Neural stimulation successfully treats depression in patients with prior ablative cingulotomy. The American Journal of Psychiatry 165(6): 687–693. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07081298.

Sartorius, A., K.L. Kiening, and P. Kirsch. 2010. Remission of major depression under deep brain stimulation of the lateral habenula in a therapy-refractory patient. Biological Psychiatry 67(2): e9–e11.

Schlaepfer, T.E., M.X. Cohen, C. Frick, M. Kosel, D. Brodesser, N. Axmacher, A.Y. Joe, M. Kreft, D. Lenartz, and V. Sturm. 2008. Deep brain stimulation to reward circuitry alleviates anhedonia in refractory major depression. Neuropsychopharmacology 33(2): 368–377. doi:10.1038/sj.npp.1301408.

Johansson, I., and N. Lynoe. 2008. Medicine and philosophy. A twenty-first century introduction. Frankfurt: Ontos Verlag.

Gaviria, M., and B. Ade. 2009. What functional neurosurgery can offer to psychiatric patients: a neuropsychiatric perspective. Surgical Neurology 71(3): 337–342.

Sachdev, P.S., and J. Sachdev. 2005. Long-term outcome of neurosurgery for the treatment of resistant depression. The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences 17(4): 478–485. doi:10.1176/appi.neuropsych.17.4.478.

Schlapfer, T.E., and B.H. Bewernick. 2009. Deep brain stimulation for psychiatric disorders–state of the art. Advances and Technical Standards in Neurosurgery 34: 37–57.

Malhi, G.S., and P. Sachdev. 2002. Novel physical treatments for the management of neuropsychiatric disorders. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 53(2): 709–719.

Juckel, G., I. Uhl, F. Padberg, M. Brune, and C. Winter. 2009. Psychosurgery and deep brain stimulation as ultima ratio treatment for refractory depression. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience 259(1): 1–7. doi:10.1007/s00406-008-0826-7.

Ottosson, J.-O., and M. Fink. 2004. Ethics in electroconvulsive therapy. New York: Brunner-Routledge.

Beauchamp, T.L., and J.F. Childress. 2009. Principles of biomedical ethics. 6th Aufl. New York: Oxford University Press.

Okun, M.S., M. Tagliati, M. Pourfar, H.H. Fernandez, R.L. Rodriguez, R.L. Alterman, and K.D. Foote. 2005. Management of referred deep brain stimulation failures: a retrospective analysis from 2 movement disorders centers. Archives of Neurology 62(8): 1250–1255. doi:10.1001/archneur.62.8.noc40425.

Hamani, C., M.P. McAndrews, M. Cohn, M. Oh, D. Zumsteg, C.M. Shapiro, R.A. Wennberg, and A.M. Lozano. 2008. Memory enhancement induced by hypothalamic/fornix deep brain stimulation. Annals of Neurology 63(1): 119–123. doi:10.1002/ana.21295.

Transcripts: Session 6: Neuroscience, Brain, and Behavior V: Deep Brain Stimulation. 2004 In President’s Council on Bioethics.

Ogren, K., and M. Sandlund. 2005. Psychosurgery in Sweden 1944–1964. Journal of the History of the Neurosciences 14(4): 353–367. doi:10.1080/096470490897692.

Diefenbach, G.J., D. Diefenbach, and A. Baumeister. 1999. Portrayal of lobotomy in the popular press: 1935–1960. Journal of the History of the Neurosciences 8(1): 60–70.

Racine, E., S. Waldman, N. Palmour, D. Risse, and J. Illes. 2007. “Currents of hope”: neurostimulation techniques in U.S. and U.K. print media. Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics 16(3): 312–316.

Patient, anonymous 2009. In DBS Trial. http://278-005.blogspot.com/. Accessed November 22, 2009.

Glannon, W. 2009. Stimulating brains, altering minds. Journal of Medical Ethics 35(5): 289–292. doi:10.1136/jme.2008.027789.

Acknowledgements

We want to thank prof. Dan Egonsson, Dr Maria Christensson and Dr Kristin Zeiler, and in addition participants of the research seminars in ethics and practical philosophy at Lund University for their helpful remarks on earlier drafts of this text. We also want to thank the two anonymous reviewers for valuable feedback. This research project was sponsored by a Linné grant, project number 60012701, from the Swedish Research Council and The Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation, project number: KAW 2004.0119.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Johansson, V., Garwicz, M., Kanje, M. et al. Beyond Blind Optimism and Unfounded Fears: Deep Brain Stimulation for Treatment Resistant Depression. Neuroethics 6, 457–471 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12152-011-9112-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12152-011-9112-x