Abstract

Karen Bennett has recently articulated and defended a “compatibilist” solution to the causal exclusion problem. Bennett’s solution works by rejecting the exclusion principle on the grounds that even though physical realizers are distinct from the mental states or properties that they realize, they necessarily co-occur such that they fail to satisfy standard accounts of causal over-determination. This is the case, Bennett argues, because the causal background conditions for core realizers being sufficient causes of their effects are identical to the “surround” conditions with which the core realizers are metaphysically sufficient the states or properties that they realize. Here we demonstrate that the background conditions for the causal sufficiency of core realizers for their effects are not identical to the core realizer’s surrounds, nor do backgrounds necessitate such surround conditions. If compatibilist solutions to exclusion can be defended, a different argument will be needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

See Bernstein (manuscript) for more on distinctness as it relates to overdetermination.

The surround may include (but not be identical to) the holding of Tx, because there may be further requirements presupposed by Tx but not included in it. See Wilson (2001). Later that will be important; but for now it is only important that p alone is not the total realizer of m.

See Keaton (2012).

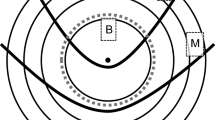

This idealization will allow us to describe especially simple physical realizers for the vending machines but is otherwise inessential.

We’ll use “device” for the physical realizer properties and states, and “machine” for the realized properties and states.

Note that the inputs and outputs—tokens, Cokes and Pepsis, button presses—are not realized properties or states. They are “physical” properties relative to the realized machine properties. In the language of Lewis (1970), “Coke,” “Pepsi,” and “button press” are O-terms.

Here we use what Bennett calls a “permissive” (2008, p. 290) and “somewhat sloppy notion of causal sufficiency according to which reasonably normal physical events… count as causally sufficient” (2003, p. 489). Q itself is only sufficient for Coke dispensing given some other conditions, including the pressing of the vending button. But we can say, after Shoemaker (2007), that Q has the forward-looking conditional power of causing a Coke to be dispensed if Button 1 is pressed.

One might worry about, for example, what happens if the machine is simply out of Pepsi but has Coke, or vice versa. The answer is that the machine we described is not Ready in that case. But our machine is very simplistic and does not check for the presence of Pepsi, so you would lose your money if you pressed the Pepsi button and it was out of Pepsi.

It is worth emphasizing the holism inherent in realization theories. Functionalism, recall, is supposed to be an improvement over behaviorism because each functional state can be defined simultaneously with every other functional state, rather than circularly. As such, human “pain” can only be had by creatures with the entire psychological profile characteristic of humans, i.e. Tx. And the property named “Ready-1” can only be had by machines that fit the specific total functional profile of Type-1 machines.

This will be the case even if the Type 2 machine is never actually in any of the states that differentiate it from a Type 1 machine.

We are grateful to Elanor Taylor for pushing us on this point.

There is nothing deep behind this thought, just the fact that counterfactuals with impossible antecedents can be true while laws with unsatisfiable antecedents are not.

For the details, see Keaton (2012).

Earlier we explained the need for surrounds by reference to the Ramsified theory Tx that must hold in order for a system to realize any one of the functional states specified by the theory. But now we see, per footnote 3, that Tx is necessary but not sufficient for the total realizer, for that must also include such properties as the holding of the laws of nature (McLaughlin 2009).

Now the whole notion of a “causal property” as contrasted with “non-causal properties” is certainly in need of explication. (As a first pass, consider that two conjunctive properties that differed only in one of their conjuncts that was not a causal property could make no difference. So on counterfactual or difference-making accounts of causation or causal explanation, such properties would fail to be causes.) Suffice it for now to say that the burden is on the defender of Bennett’s strategy to show that causal background conditions are ever identical to or necessitate surrounds.

If all those relations are actualized causal relations, then it will be p* (p plus those relations) that is by itself sufficient for m. Then m is not reducible to p, but only because p was the wrong candidate—m is instead reducible to p*. The sufficiency of p* for m is compatible with Distinctness, and so not strictly speaking a form of reductionism as defined by Bennett. But if p* by itself—without any surround—is metaphysically sufficient for m, then there is reason to doubt that p* and m are wholly distinct. If property individuation is hyperintensional, then it is possible that some realized properties/states have modally unique realizers. Perhaps being god is the modally unique realizer of being a perfect being, or being the number 2 is the modally unique realizer of being the smallest prime number. We don’t know of anyone who holds that the mental is not reducible to the physical but has the physical as its modally unique realizer. Whatever motivation one might have for such a view would be quite different than the usual motivations for non-reductive physicalists.

Recall that Lewis ultimately appeals to brute force: taking the disjunction of the conjunctions of most of the laws (i.e., platitudes) in the theory (1972), to ensure that at least one disjunct is a conjunction of only true claims.

Our thanks to Carl Gillett for suggesting this possible saving maneuver.

We focus on the case of the background necessitating the surround, because that is what is relevant to assessing (O2). You might wonder whether the surround could necessitate the background. If so, then one could try to argue that (O1) is only vacuously true. But Bennett, and advocates of Distinctness in general, take (O1) to be non-vacuously true on the grounds of multiple realization. Be that as it may, the surround does not necessitate the causal background conditions, and for the same reason that they do not have a common necessitator: it is common for the surround to be present without the causal background conditions.

See, e.g., Dretske (1988).

References

Bennett, K. (2003). Why the exclusion problem seems intractable and how, just maybe, to tract it. Noûs, 37(3), 471–497.

Bennett, K. (2008). Exclusion again. In J. Hohwy & J. Kallestrup (Eds.), Being reduced. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bernstein, S. manuscript. Overdetermination underdetermined.

Block, N. (1978). Troubles with functionalism. In C. W. Savage (Ed.), Minnesota studies in the philosophy of science (Vol. IX). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Bontly, T. (2002). The supervenience argument generalizes. Philosophical Studies, 109, 75–96.

Christensen, J., & Kallestrup, J. (2012). Counterfactuals and downward causation: A reply to Zhong. Analysis, 72(3), 513–517.

Dretske, F. (1988). Explaining behavior. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Funkhouser, E. (2006). The determinable–determinate relation. Noûs, 40, 548–569.

Haug, M. (2010). Realization, determination, and mechanisms. Philosophical Studies, 150, 313–330.

Keaton, D. (2012). Kim’s supervenience argument and the nature of total realizers. European Journal of Philosophy, 20(2), 243–259.

Kim, J. (1998). Mind in a physical world: An essay on the mind–body problem and mental causation. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Kim, J. (2005). Physicalism, or something near enough. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Lewis, D. (1970). How to define theoretical terms. Journal of Philosophy, 67(13), 427–446.

Lewis, D. (1972). Psychophysical and theoretical identifications. Australasian Journal of Philosophy, 50, 249–258.

McLaughlin, B. P. (2009). Review of Sydney Shoemaker, Physical Realization. Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews. Retrieved November 18, 2013, from http://ndpr.nd.edu/news/24086-physical-realization/.

Shoemaker, S. (1981). Some varieties of functionalism. Philosophical Topics, 12(1), 83–118.

Shoemaker, S. (2007). Physical realization. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wilson, R. (2001). Two views of realization. Philosophical Studies, 104, 1–31.

Yablo, S. (1992). Mental causation. Philosophical Review, 101, 245–280.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for feedback from Carl Gillett, Tom Bontly, Sara Bernstein, Alyssa Ney, Lenny Clapp, Brian McLaughlin, and Elanor Taylor. This work was first presented at the workshop, “The Metaphysics of Mind and Brain: Realization, Mechanisms, and Embodiment” organized by Sven Walter and Beate Krickel. Later versions were presented at the Southern Society for Philosophy and Psychology and the Pacific Division of the American Philosophical Association. We thank the organizers and participants in those meetings. Authorship is equal, and authors’ names are listed alphabetically.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Keaton, D., Polger, T.W. Exclusion, still not tracted. Philos Stud 171, 135–148 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-013-0246-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-013-0246-z