-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

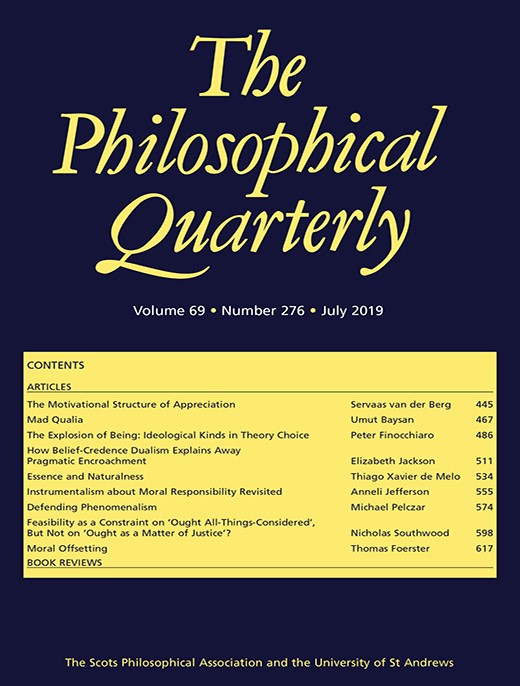

Ian James Kidd, Inner Virtue, The Philosophical Quarterly, Volume 69, Issue 276, July 2019, Pages 641–644, https://doi.org/10.1093/pq/pqy055

Close - Share Icon Share

Extract

Nicolas Bommarito elegantly argues that ‘someone's inner life [can] make them a morally better or worse person’ (p. 3). Although actions matter morally, so do pleasures, emotions, habits of attention, and other aspects of our inner life, even if they’re never expressed in outer behaviour. Underlying the thesis is moral care, a disposition ‘to care about moral goods’, ‘the only unconditionally good trait one can have’ (p. 172). Our moral cares and concerns are manifested across our actions, attentions, emotions, pleasures, and thoughts. ‘It's not merely what we do that makes us virtuous or vicious’, says Bommarito, ‘but what happens to us on the inside’, too (p. 6).

The book has many virtues. The writing is crisp and personable, the examples engaging and accessible, the philosophizing pleasingly informed by everyday experience. Bommarito also engages Buddhism, Confucianism, and Simone Weil and Iris Murdoch, always using them thoughtfully and productively, not as a trendy gesture to diversity. Such rich resources help persuade us that a morally good person has ‘a certain kind of inner life’, an idea fallen from view due to a late modern ethical focus on actions and consequences (p. 6). The inner life of the virtuous, moreover, has ‘desirable pluralities’, with the emotions, thoughts, pleasures, and attentional habits of virtuous people showing a pleasing ‘cultural and personal diversity’ (pp. 41, 172).