Abstract

In this article, I provide a guide to some current thinking in empirical moral psychology on the nature of moral intuitions, focusing on the theories of Haidt and Narvaez. Their debate connects to philosophical discussions of virtue theory and the role of emotions in moral epistemology. After identifying difficulties attending the current debate around the relation between intuitions and reasoning, I focus on the question of the development of intuitions. I discuss how intuitions could be shaped into moral expertise, outlining Haidt’s emphasis on innate factors and Narvaez’s account in terms of a social-cognitive model of personality. After a brief discussion of moral relativism, I consider the implications of the account of moral expertise for our understanding of the relation between moral intuitions and reason. I argue that a strong connection can be made if we adopt a broad conception of reason and a narrow conception of expertise.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

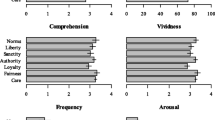

Another topic that has dominated debates in moral psychology is the scope of morality. Haidt argues philosophers and psychologists have been mistaken to think of morality in terms of harm and fairness, the central concepts of traditional consequentialist and deontological theories. In this, he is joined by many virtue theorists, who tend to favour a plurality of ‘thick’ concepts and welcome the contribution of emotions to moral theory. This package—emotion, intuition, virtue, pluralism—is favoured by the discussion below.

That emotions involve considerable cognition of this kind is widely accepted in psychology (Lazarus 1991), although some question whether the mechanisms involved deserve the title ‘cognition’ (Prinz 2004). But this cognitivism should not be confused with, and does not entail, any form of metaethical cognitivism. The facts cognised in the psychological theories are social facts (motives, meanings, etc.); they are not truths about the objective value of features of situations. Metaethical cognitivists and non-cognitivists can agree on this even as they dispute the vexed question of whether moral intuitions and judgments are cognitions of distinct evaluative properties.

There is also a large body of literature implicating emotional involvement in moral motivation and action, but as our concern here is moral judgment, we may set that aside. It is notable, however, that Haidt does not always observe this distinction, inappropriately taking such evidence as supportive of his model.

Haidt oversimplifies, then, when he speaks of children having ‘crude and inappropriate’ evaluative emotional responses until they learn the ‘application rules for their culture’ (Haidt and Bjorklund 2008: 206). More than learning rules will be needed to ‘get it right’.

There are two qualifications here. First, our focus in discussing moral expertise will be in relation to moral judgment, rather than moral action (about which Haidt’s model has little to say). Second, we may wish to draw a distinction between moral expertise and virtue in terms of their sensitivity to objective questions of human flourishing—see note 17.

Prior to 2012, these received different names, viz. harm/care, fairness/reciprocity, in-group/loyalty, authority/respect, and purity/sanctity.

While Haidt’s official commitment is only to ‘evolutionary preparedness’, he favours a modular account of foundations, using Sperber’s (2005) flexible concept of a module. On this view, the claim is that moral intuitions are generated by processes that are modular ‘to some interesting degree’, which may vary from one module to another. The processes underlying the five foundations may be more or less domain-specific and only partially encapsulated, and rather than generate outputs directly themselves, they can be thought of as ‘learning modules’—innate learning mechanisms that generate more specific modules over the course of development within a particular culture (disgust may operate like this, such that we learn to become automatically disgusted at certain things). Whether a modular interpretation of the structure of intuitions is right in the end is not something Haidt battles for, even allowing that what is learned are not specific modules but ‘bits of subcultural expertise’ (Haidt and Joseph 2007: 381), connections between perceptions of certain situations and emotional evaluative responses that cannot be easily controlled or revised.

Narvaez is sceptical about modules. While we have many specialized subcortical networks, many of which we share with other mammals, ‘there is no comparable evidence in support of highly resolved genetically dictated adaptations that produce socio-emotional cognitive strategies within the circuitry of the human neocortex’ (Panksepp and Panksepp 2000: 111). The idea of sophisticated cognitive modules has no basis in neuroscientific fact. The neocortex has a high degree of plasticity, even as it is grounded and structured by the propensities of subcortical processes (Panksepp 1998). Narvaez’s interpretation is to think of the innate pre-structuring of moral intuitions in terms of units resulting from experience structured by this combination of subcortical adaptations and neocortical plasticity.

Given how loosely Haidt is willing to use the term ‘module’ in this context, perhaps this alternative is really a matter of emphasis. As Panksepp (1998) shows, emotions and concerns are substantially underpinned by subcortical adaptations. Importantly, on either model, there is some innate structuring.

Many intuitions related to loyalty and authority relate to the ethics of security, while many intuitions related to care and fairness map onto the ethics of engagement. The ethics of imagination defends the role of moral reasoning about which Haidt is sceptical. It is interesting to note that it involves what we may characterise as balancing four of Haidt’s five foundations—Narvaez talks of reciprocity between the law and the individual (balancing fairness and care with authority) and coordinating community and individual interests (balancing fairness and care with loyalty).

Built into Narvaez’s model is a hierarchy of moral concerns and emotions, which she draws upon in her account of moral development. It is a hierarchy that Haidt repeatedly emphasises reflects the distinctive morality of educated liberals, and not one he believes can be grounded in fact. Of course, we needn’t accept the hierarchy along with the neuroscience, but Narvaez (2013c) provides evidence that connects the security ethic to poorer psychological functioning, in particular, insecure attachment and the use of aggression or withdrawal in social interaction, while Wright and Baril (2013) argue that it is connected to psychological defence.

Haidt discusses individual differences in moral judgment, emphasising not what is learned, but what is innate. Twin studies have shown monozygotic twins are more similar than dyzygotic twins, and that monozygotic twins reared apart are almost as similar as those reared together (Bouchard 2004). Given this, we can expect innate temperament to play an important role in moral psychology. So Haidt speculates that the strength of intuitions deriving from the five foundations will differ between the foundations within one person and will differ between people for the same foundation. Again, given that children are differentially responsive to reward and punishment (Kochanska 1997), they will respond differently to attempts to ‘tune up’ their intuitions through socialisation. Some may be more prone to social persuasion than others. Differences in cognitive ability will be reflected in differential use of the four forms of moral reasoning (post-hoc, reasoned persuasion, reasoned judgment, private reflection). All this gives us difference, but not in expertise.

The model derives from the work of Mischel and Shoda (Mischel 1968; Mischel and Shoda 1995; Cervone and Shoda 1999), and has become widely accepted in the wake of the situationism-character debate. That debate considered evidence that people’s behaviour is so malleable by situational influences that the existence of traits of character is called into question. Social-cognitive models have been a popular solution, holding that behaviour is the result of a dynamic interaction between genuine features of the person and the situation. Once situations are categorised by how the subject interprets them, then there is strong evidence of stable and predictable individual behavioural responses across diverse situations with similar meaning. For an account of the debate and detailed defence and elaboration of the model, see Snow (2010).

For example, aggressive people are more likely to automatically notice and recall hostile cues (Zelli et al. 1995), authoritarian people are more likely to automatically infer others are authoritarian from prompts that are ambiguous (e.g. enjoying military parades) (Uleman et al. 1986), and how one understands a moral narrative is strongly influenced by one’s chronically available moral schemas (Narvaez 1998; see also Narvaez et al. 2006).

Narvaez (2013c) relates moral development to her three ‘ethics’. I have left out this additional detail to avoid over-complication. In brief, she argues that whether an individual acquires a dominant security ethic or a dominant engagement and/or imagination ethic is heavily influenced by interpersonal relations in early childhood. The former is the ‘default’ when nurturance is poor, while the latter develops when children receive warm, responsive care. On her account, experts will, of course, need to develop an imaginative ethic. This line of evidence relates to remarks made at the end of Sect. 4 and the discussion of defence (which is correlated with insecure attachment) in Sect. 5.4.

Haidt’s views on the relation between moral development and the self have shifted. Haidt and Joseph (2007) hold that what is learned are the skills of perception and response. Haidt et al. (2009) and Graham et al. (2013) adopt McAdams (1995) three-level model of the self, but, as noted, accept that their account requires development. Level I is very abstract traits (the ‘Big Five’). Level II involves ‘personal concerns’—the kind of thing McAdams has in mind (1995: 376) maps closely on to the specific contents of schemas and social-cognitive units, demonstrating that Narvaez’s account can, to a significant extent, be made compatible with that of McAdams’. Level III concerns autobiographical narrative. However, McAdams’ levels are defined epistemologically (the terms in which we may know a person), while Narvaez provides an account of how personality functions. For this reason, I would argue that her account is more satisfactory.

Part of the reason for Haidt’s reticence on the development of expertise is his general reluctance to talk of ‘better’ and ‘worse’ in the domain of moral psychology.

Narvaez is thus mistaken when she accuses Haidt of adopting moral relativism. At times, he does appear to define virtue in these terms, e.g. ‘a fully enculturated person is a virtuous person’ (Haidt and Bjorklund 2008: 29)—as though it were sufficient for virtue to adopt whatever norms one’s culture holds. But his official position is one of pluralism, not simple relativism.

At this point, we may wish to make a distinction between moral expertise that is expertise only in terms of the local culture’s values, and virtue, which is additionally sensitive to truths about human flourishing. Narvaez and Haidt don’t draw this distinction, and equate the two as we have done thus far. Even allowing for the distinction, epistemologically it is the more helpful to take the case of moral expertise as virtue as the basic case, and explain why moral expertise does not amount to virtue in the instances in which it falls short.

He also suggests that if one were to claim this that would entail that any intuitions could be teachable. But this doesn’t follow: what can be acquired from experience may nevertheless be shaped and constrained by what is innate, so that not any intuition can be developed.

Compare: a similar ability to imagine future positions in chess is necessary for chess expertise, its development requires a great deal of practice not mere teaching, and it does not transfer to a general ability to imagine future scenarios in other domains.

Given the difficulties of developing moral expertise, there is a further question of how best to encourage moral behaviour (education? public dialogue? manipulating situations?). But that is a further question, and should not be confused for an account of the nature of moral intuitions and expertise.

Chen and Chaiken (1999) identify three motives that drive cognitive processing: accuracy, defence, and impression management, and argue that accuracy is frequently overridden by the other two. Haidt discusses ‘impression management’ at length, but says little about defence and its impact on our moral intuitions. In raising the matter of defence here, we will have covered all three motives.

This is, however, complicated by IQ—see Cramer (2006: Chap. 8).

Vaillant (1993: 132, Table 4) notes that of those in the top 20 % on a scale of psychosocial adjustment at 65 years old, 50 % still use less than mature defences, and the percentage for those lower on the scale is considerably higher. Cramer (2006: 204) notes that neurotic defences are likely to survive into adulthood, and remarks on the widespread distribution in ‘normal’ samples of characteristics defining psychological disorders, e.g. depressive tendencies, phobias, pathological aggression, antisocial traits, etc. that are associated with the use of defence (224, 235).

References

Abernathy CM, Hamm RM (1995) Surgical intuition. Hanley & Belfus, Philadelphia

Andersen SM, Chen S (2002) The relational self: an interpersonal social-cognitive theory. Psychol Rev 109:619–645

Andersen SM, Thorpe JS (2009) An IF–THEN theory of personality: significant others and the relational self. J Res Pers 43(2):163–170

Anderson SW, Bechara A, Damasio H, Tranel D, Damasio AR (1999) Impairment of social and moral behavior related to early damage in human prefrontal cortex. Nat Neurosci 2:1032–1037

Annas J (2011) Intelligent virtue. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Badhwar N (2008) Is realism really bad for you? A realistic response. J Philos 105:85–107

Bargh JA, Chartrand TL (1999) The unbearable automaticity of being. Am Psychol 54:462–479

Bargh JA, Lombardi WJ, Higgins ET (1988) Automaticity of person × situation effects on impression formation: it’s just a matter of time. J Pers Soc Psychol 55:599–605

Berlin I (2001) My intellectual path. In: Hardy H (ed) The power of ideas. Princeton University Press, Princeton, pp 1–23

Blair RJR (1995) A cognitive developmental approach to morality: investigating the psychopath. Cognition 57:1–29

Blair RJR (1997) Moral reasoning and the child with psychopathic tendencies. Pers Individ Differ 26:731–739

Blair RJR (2007) The amygdala and ventromedial prefrontal cortex in morality and psychopathy. Trends Cogn Sci 11:387–392

Boehm C (1999) Hierarchy in the forest: the evolution of egalitarian behavior. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Boehm C (2012) Moral origins: the evolution of virtue, altruism, and shame. Basic, New York

Bouchard TJ Jr (2004) Genetic influence on human psychological traits: a survey. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 13(4):148–151

Cantor N (1990) From thought to behaviour: “having” and “doing” in the study of personality and cognition. Am Psychol 45:735–750

Cassidy J, Shaver PR (eds) (1999) Handbook of attachment: theory, research and clinical applications. Guilford Press, New York

Cervone D, Shoda Y (1999) Social-cognitive theories and the coherence of personality. In: Cervone D, Shoda Y (eds) The coherence of personality. Guilford, New York, pp 3–36

Chaiken S, Trope Y (eds) (1999) Dual process theories in social psychology. Guilford, New York

Chen S, Chaiken S (1999) The heuristic-systematic model in its broader context. In: Chaiken S, Trope Y (eds) Dual process theories in social psychology. Guilford, New York, pp 73–96

Ciancolo AT, Matthew C, Sternberg RJ, Wagner RK (2006) Tacit knowledge, practical intelligence and expertise. In: Ericsson KA, Charness N, Feltovich PJ, Hoffman RR (eds) The Cambridge handbook of expertise and expert performance. Cambridge University Press, New York, pp 613–632

Cosmides L, Tooby J (2004) Knowing thyself: the evolutionary psychology of moral reasoning and moral sentiments. In: Freeman RE, Werhane P (eds) The Ruffin Series in Business Ethics, vol 4. Business, Science, and Ethics. Society for Business Ethics, Charlottesville, VA, pp 93–128

Cramer P (2006) Protecting the self: defense mechanisms in action. Guilford Press, New York

Damasio A (1994) Descartes’ error. Putnam, New York

Damasio A (1999) The feeling of what happens. Harcourt and Brace, New York

de Waal F (1982) Chimpanzee politics: power and sex among apes. Jonathan Cape, London

DeVries R, Zan B (1994) Moral classrooms, moral children: creating a constructivist atmosphere in early education. Teachers College Press, New York

Dijksterhuis A (2010) Automaticity and the unconscious. In: Fiske S, Gilbert D, Lindzey G (eds) Handbook of social psychology, vol I, 5th edn. McGraw-Hill, New York, pp 228–267

Ditto PH, Pizarro DA, Tannenbaum D (2009) Motivated moral reasoning. In: Bartels DM, Bauman CW, Skitka LJ, Medin DL (eds) The psychology of learning and motivation, vol 50. Academic Press, Burlington, pp 307–338

Dreyfus HL, Dreyfus SE (1990) What is moral maturity? a phenomenological account of the development of ethical expertise. In: Rasmussen D (ed) Universalism vs. communitarianism, MIT Press, Boston, pp 237–264

Dupre J (2001) Human nature and the limits of science. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Ericsson KA, Smith J (1991) Toward a general theory of expertise. Cambridge University Press, New York

Feltovich PJ, Prietula MJ, Ericsson KA (2006) Studies of expertise from psychological perspectives. In: Ericsson KA, Charness N, Feltovich PJ, Hoffman RR (eds) The Cambridge handbook of expertise and expert performance. Cambridge University Press, New York, pp 41–68

Feshbach ND (1989) Empathy training and prosocial behavior. In: Grobel J, Hinde RA (eds) Aggression and war: their biological and social bases. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 101–111

Fiske AP (1991) Structures of social life. Free Press, New York

Foot P (2001) Natural goodness. Clarendon Press, Oxford

Frankish K (2009) Systems and levels. In: Evans J, Frankish K (eds) Dual-system theories and the personal subpersonal distinction. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 89–107

Frensch PA (1998) One concept, multiple meanings: on how to define the concept of implicit learning. In: Stadler MA, Frensch PA (eds) Handbook of implicit learning. Sage, Thousand Oaks, pp 47–104

Fry DP, Souillac G (2013) The relevance of nomadic forager studies to moral foundations theory: moral education and global ethics in the twenty-first century. J Moral Educ 42(3):346–359

Gardner S (2000) Psychoanalysis and the personal/sub-personal distinction. Philos Explor 3(1):96–119

Gawronski B (2004) Theory-based bias correction in dispositional inference: the fundamental attribution error is dead, long live the correspondence bias. Eur Rev Soc Psychol 15:183–217

Gazzaniga MS (1985) The social brain. Basic Books, New York

Gigerenzer G (2008) Moral intuition = fast and frugal heuristics? In: Sinnott-Armstrong W (ed) Moral psychology, vol 2. The cognitive science of morality: intuition and diversity. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, pp 1–26

Glaser J, Kihlstrom JF (2005) Compensatory automaticity: unconscious volition is not an oxymoron. In: Hassin RR, Uleman JS, Bargh JA (eds) The new unconscious. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 171–195

Goldie P (2007) Seeing what is the kind thing to do. Dialectica 61(3):347–361

Gollwitzer PM, Bayer UC, McCulloch KC (2005) The control of the unwanted. In: Hassin RR, Uleman JS, Bargh JA (eds) The new unconscious. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 485–515

Graham J, Haidt J, Koleva S, Motyl M, Iyer R, Wojcik SP, Ditto PH (2013) Moral foundations theory: the pragmatic validity of moral pluralism. In: Devine P, Plant A (eds) Advances in experimental social psychology, vol 47. Academic Press, Burlington, pp 55–130

Greene JD, Sommerville RB, Nystrom LE, Darley JM, Cohen JD (2001) An fMRI study of emotional engagement in moral judgment. Science 293:2105–2108

Greenspan SI, Shanker SI (2004) The first idea. Da Capo Press, Cambridge

Haidt J (2001) The emotional dog and its rational tail: a social intuitionist approach to moral judgment. Psychol Rev 108(4):814–834

Haidt J (2006) The happiness hypothesis. Arrow Books, London

Haidt J (2010) Moral psychology must not be based on faith and hope: commentary on narvaez (2010). Perspect Psychol Sci 5(2):182–184

Haidt J (2012) The righteous mind. Penguin, London

Haidt J, Bjorklund F (2008) Social intuitionists answer six questions about moral psychology. In: Sinnott-Armstrong WA (ed) Moral psychology, vol 2. MIT Press, Cambridge, pp 181–217

Haidt J, Hersh MA (2001) Sexual morality: the cultures and reasons of liberals and conservatives. J Appl Soc Psychol 31:191–221

Haidt J, Joseph C (2007) The moral mind: how 5 sets of innate moral intuitions guide the development of many culture-specific virtues, and perhaps even modules. In: Carruthers P, Laurence S, Stich S (eds) The innate mind, vol 3. Oxford University Press, New York, pp 367–391

Haidt J, Kesebir S (2010) Morality. In: Fiske S, Gilbert D, Lindzey G (eds) Handbook of social psychology, 5th edn. McGraw-Hill, New York, pp 797–832

Haidt J, Graham J, Joseph C (2009) Above and below left–right: ideological narratives and moral foundations. Psychol Inq 20(2–3):110–119

Hamlin JK, Wynn K, Bloom P (2007) Social evaluation by preverbal infants. Nature 450:557–560

Hammond KR (2000) Judgments under stress. Oxford University Press, New York

Harman G, Mason K, Sinnott-Armstrong W (2010) Moral reasoning. In: Doris J et al (eds) The moral psychology handbook. Oxford University Press, New York

Hassin RR, Uleman JS, Bargh JA (eds) (2005) The new unconscious. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Hauser MD (2006) Moral minds: how nature designed our universal sense of right and wrong. Ecco Press, New York

Hauser MD, Young L, Cushman F (2008) Reviving Rawls’s linguistic analogy: operative principles and the causal structure of moral actions. In: Sinnott-Armstrong W (ed) Moral psychology, vol 2. The cognitive science of morality: intuition and diversity. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, pp 107–144

Hogarth RM (2001) Educating intuition. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Huebner B (2011) Critiquing empirical moral psychology. Philos Soc Sci 41(1):50–83

Hursthouse R (1999) On virtue ethics. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Jacobson D (2005) Seeing by feeling: virtues, skills, and moral perception. Ethical Theory Moral Pract 8:387–409

Johnson KE, Mervis CB (1997) Effects of varying levels of expertise on the basic level of categorization. J Exp Psychol Gen 126:248–277

Juarrero A (1999) Dynamics in action: intentional behavior as a complex system. MIT Press, Cambridge

Keil FC, Wilson RA (2000) Explaining explanations. In: Keil FC, Wilson RA (eds) Explanation and cognition. MIT Press, Cambridge, pp 1–18

Kennett J, Fine C (2009) Will the real moral judgment please stand up? Ethical Theory Moral Pract 12(1):77–96

Kiehl KA (2006) A cognitive neuroscience perspective on psychopathy: evidence for paralimbic system dysfunction. Psychiatry Res 142:107–128

Klinger E (1978) Modes of normal conscious flow. In: Pope KS, Singer JL (eds) The stream of consciousness: scientific investigations into the flow of human experience. Plenum, New York, pp 225–258

Kochanska G (1997) Multiple pathways to conscience for children with different temperaments: from toddlerhood to age 5. Dev Psychol 33:228–240

Koenigs M, Young L, Adolphs R, Tranel D, Cushman F, Hauser M, Damasio A (2007) Damage to the prefrontal cortex increases utilitarian moral judgments. Nature 446:865–866

Kuhn D (1991) The skills of argument. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Kunda Z (1990) The case for motivated reasoning. Psychol Bull 108(3):480–498

Kunda Z, Spencer SJ (2003) When do stereotypes come to mind and when do they color judgment? A goal-based theoretical framework for stereotype activation and application. Psychol Bull 129(4):522–544

Lacewing M (2014) Emotion and the virtues of self-understanding. In: Roeser S, Todd C (eds) Emotion and value. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Lapsley D, Narvaez D (2004) A social-cognitive approach to the moral personality. In: Lapsley D, Narvaez D (eds) Moral development, self and identity. Erlbaum, Mahwah, pp 189–212

Lapsley DK, Hill PL (2008) On dual processing and heuristic approaches to moral cognition. J Moral Educ 37:313–332

Lazarus RS (1991) Cognition and motivation in emotion. Am Psychol 46:352–367

Lerner JS, Tetlock PE (2003) Bridging individual, interpersonal, and institutional approaches to judgment and decision making: the impact of accountability on cognitive bias. In: Schneider SL, Shanteau J (eds) Emerging perspectives on judgment and decision research. New York, Cambridge, pp 431–457

Lerner JS, Goldberg JH, Tetlock PE (1998) Sober second thought: the effects of accountability, anger, and authoritarianism on attributions of responsibility. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 24:563–574

Lewis MD (2009) Desire, dopamine, and conceptual development. In: Calkins SD, Bell MA (eds) Child development at the intersection of emotion and cognition. American Psychological Association, Washington, DC, pp 175–199

Lilienfeld SO, Ammirati R, Landfield K (2009) Giving debiasing away: can psychological research on correcting cognitive errors promote human welfare? Perspect Psychol Sci 4:390–398

MacLean PD (1990) The triune brain in evolution. Plenum, New York

McAdams DP (1995) What do we know when we know a person? J Pers 63(3):365–396

McDowell J (1979) Virtue and reason. Monist 62:331–350

McDowell J (1985) Values and secondary qualities. In: Honderich T (ed) Morality and objectivity: a tribute to J.L. Mackie. Routledge, London, pp 110–129

Mercier H, Sperber D (2011) Why do humans reason? Arguments for an argumentative theory. Behav Brain Sci 34:57–111

Mikhail J (2007) Universal moral grammar: theory, evidence, and the future. Trends Cogn Sci 11:143–152

Mischel W (1968) Personality and assessment. Wiley, Hoboken

Mischel W, Shoda Y (1995) A cognitive-affective system theory of personality: reconceptualizing situations, dispositions, dynamics, and invariance in personality structure. Psychol Rev 102:246–268

Moll J, de Oliveira-Souza R, Bramati I, Grafman J (2002) Functional networks in emotional moral and nonmoral social judgments. NeuroImage 16:696–703

Moll J, de Oliveira-Souza R, Eslinger PJ (2003) Morals and the human brain: a working model. NeuroReport 14:299–305

Monteith MJ, Ashburn-Nardo L, Voils CI, Czopp AM (2002) Putting the brakes on prejudice: on the development and operation of cues for control. J Pers Soc Psychol 83:1029–1050

Moskowitz GB, Skurnik L, Galinsky AD (1999) The history of dual process notions, and the future of pre-conscious control. In: Chaiken S, Trope Y (eds) Dual process theories in social psychology. Guilford Press, New York, pp 12–36

Narvaez D (1998) The influence of moral schemas on the reconstruction in eighth-graders and college students. J Educ Psychol 90:13–24

Narvaez D (2005) Integrative ethical education. In: Killen M, Smetana J (eds) Handbook of moral development. Erlbaum, Mahwah, pp 703–733

Narvaez D (2008a) The social intuitionist model: some counter-intuitions. In: Sinnott-Armstrong WA (ed) Moral psychology, vol 2. MIT Press, Cambridge, pp 233–240

Narvaez D (2008b) Triune ethics: the neurobiological roots of our multiple moralities. New Ideas Psychol 26:95–119

Narvaez D (2010) Moral complexity the fatal attraction of truthiness and the importance of mature moral functioning. Perspect Psychol Sci 5(2):163–181

Narvaez D (2013a) Wisdom as mature moral functioning: insights from developmental psychology and neurobiology. In: Jones M, Lewis P, Reffitt K (eds) Toward human flourishing: character, practical wisdom and professional formation. Mercer University Press, Macon

Narvaez D (2013b) The 99 percent—development and socialization within an evolutionary context. In: Fry D (ed) War, peace and human nature. Oxford University Press, New York, pp 341–357

Narvaez D (2013c) Neurobiology and moral mindset. In: Heinrichs K, Oser F, Lovat T (eds) Handbook of moral motivation. Sense, Rotterdam, pp 323–340

Narvaez D, Bock T (2014) The development of virtue. In: Nucci L, Narvaez D (eds) Handbook of moral and character education, 2nd edn. Routledge, New York

Narvaez D, Lapsley DK (2005) The psychological foundations of everyday morality and moral expertise. In: Lapsley D, Power C (eds) Character psychology and character education. University of Notre Dame Press, Notre Dame, pp 140–165

Narvaez D, Getz I, Rest JR, Thoma S (1999) Individual moral judgment and cultural ideologies. Dev Psychol 35:478–488

Narvaez D, Lapsley DK, Hagele S, Lasky B (2006) Moral chronicity and social information processing: tests of a social cognitive approach to the moral personality. J Res Pers 40:966–985

Nelson EE, Panksepp J (1998) Brain substrates of infant–mother attachment: contributions of opioids, oxytocin, and norepinephrine. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 22:437–452

Nickerson RS (1994) The teaching of thinking and problem solving. In: Sternberg RJ (ed) Thinking and problem solving. Academic Press, San Diego, pp 409–449

Nickerson RS (1998) Confirmation bias: a ubiquitous phenomenon in many guises. Rev Gen Psychol 2(2):175–220

Nisbett RE, Wilson TD (1977) Telling more than we can know: verbal reports on mental processes. Psychol Rev 84:231–259

Nussbaum M (1993) Non-relative virtue. In: Nussbaum M, Sen A (eds) The quality of life. Clarendon Press, Oxford, pp 242–269

Panksepp J (1998) Affective neuroscience. Oxford University Press, New York

Panksepp J, Panksepp JB (2000) The seven sins of evolutionary psychology. Evol Cogn 6(2):108–131

Pascarella E, Terenzini P (1991) How college affects students. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco

Payne B, Jacoby LL, Lambert AJ (2005) Attitudes as accessibility bias: dissociating automatic and controlled processes. In: Hassin RR, Uleman JS, Bargh JA (eds) The new unconscious. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 393–420

Perkins DN, Farady M, Bushey B (1991) Everyday reasoning and the roots of intelligence. In: Voss JF, Perkins DN, Segal JW (eds) Informal reasoning and education. Erlbaum, Hillsdale, pp 83–105

Pizarro DA, Bloom P (2003) The intelligence of the moral intuitions: comments on Haidt (2001). Psychol Rev 110:193–196

Plous S (2003) The psychology of prejudice, stereotyping, and discrimination: an overview. In: Plous S (ed) Understanding prejudice and discrimination. McGraw-Hill, New York, pp 3–48

Power FC, Higgins A, Kohlberg L (1989) Kohlberg’s approach to moral education. Columbia University Press, New York

Prinz J (2004) Gut reactions. Oxford University Press, New York

Prinz J (2007) The emotional construction of morals. Oxford University Press, New York

Railton P (forthcoming) The affective dog and its rational tale. Ethics

Rest JR (1979) Development in judging moral issues. University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis

Rest JR, Narvaez D, Bebeau MJ, Thoma SJ (1999) Postconventional moral thinking: a neo-Kohlbergian approach. Erlbaum, Mahwah, NJ

Sauer H (2011) Social intuitionism and the psychology of moral reasoning. Philos Compass 6(10):708–721

Sauer H (2012) Educated intuitions. Automaticity and rationality in moral judgement. Philos Explor 15(3):255–275

Schnall S, Haidt J, Clore GL, Jordan AH (2008) Disgust as embodied moral judgment. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 34:1096–1109

Schore A (2001) The effects of a secure attachment on right brain development, affect regulation and infant mental health. Infant Ment Health J 22:201–269

Schore A (2003) Affect dysregulation and disorders of the self. Norton, New York

Selman RL (2003) The promotion of social awareness: powerful lessons from the partnership of developmental theory and classroom practice. Russell Sage, New York

Snow NE (2010) Virtue as social intelligence: an empirically grounded theory. Routledge, New York

Sperber D (2005) Modularity and relevance: how can a massively modular mind be flexible and context-sensitive? In: Carruthers P, Laurence S, Stich S (eds) The innate mind: structure and contents. New York, Oxford, pp 53–68

Stern DN (1985) The interpersonal world of the human infant. Basic Books, New York

Sternberg RJ (1998) Abilities are forms of developing expertise. Educ Res 3:22–35

Sternberg RJ (1999) Intelligence as developing expertise. Contemp Educ Psychol 24:359–375

Taylor S, Brown J (1988) Illusion and well-being: a social psychological perspective on mental health. Psychol Bull 103:193–210

Taylor S, Brown J (1994) Positive illusions and well-being revisited: separating fact from fiction. Psychol Bull 116:21–27

Thoma SJ, Barnett R, Rest J, Narvaez D (1999) Political identity and moral judgment development using the defining issues test. Br J Soc Psychol 38:103–111

Thompson RA (1988) Early sociopersonality development. In: Damon W, Eisenberg N (eds) Handbook of child psychology. Social, emotional, and personality development, vol 3, 5th edn. Wiley, Hoboken, NJ, pp 25–104

Tiberius V (2008) The reflective life. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Trope Y, Fishbach A (2005) Going beyond the motivation given: self-control and situational control over behaviour. In: Hassin RR, Uleman JS, Bargh JA (eds) The new unconscious. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 537–565

Trout JD (2009) The empathy gap. Viking/Penguin, New York

Uleman JS, Winborne WC, Winter L, Schechter D (1986) Personality differences in spontaneous trait inferences at encoding. J Pers Soc Psychol 51:396–404

Vaillant GE (1993) The wisdom of the ego. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Vaillant GE (2000) Defense mechanisms. In: Kazdin A (ed) Encyclopedia of psychology, vol 2. American Psychological Press, Washington, DC, pp 454–457

Varela F (1999) Ethical know-how. Stanford University Press, Stanford

Warneken F, Tomasello M (2006) Altruistic helping in human infants and young chimpanzees. Science 311:1301–1303

Wegner D, Bargh J (1998) Control and automaticity in social life. In: Fiske S, Gilbert D, Lindzey G (eds) Handbook of social psychology, vol I, 4th edn. McGraw-Hill, New York, pp 446–496

Westen D (2007) The political brain. Public Affairs, New York

Wheatley T, Haidt J (2005) Hypnotic disgust makes moral judgments more severe. Psychol Sci 16:780–784

Wiggins D (1987) Needs, values, truth. Blackwell, Oxford

Willingham DT (2007) Critical thinking: why is it so hard to teach? Am Educ 31:8–19

Wilson TD (2002) Strangers to ourselves: discovering the adaptive unconscious. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Wright JC, Baril GL (2013) Understanding the role of dispositional and situational threat sensitivity in our moral judgments. J Moral Educ 42(3):383–397

Zelli A, Huesmann LR, Cervone D (1995) Social inference and individual differences in aggression: evidence for spontaneous judgements of hostility. Aggress Behav 21:405–417

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Thanks to Jonathan Haidt and Darcia Narvaez for comments, corrections, and the provision of additional references, including forthcoming work. Thanks also to two anonymous reviewers for comments and corrections.