Abstract

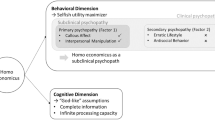

Public figures’ transgressions attract considerable media attention and public interest. However, little is understood about the impact of celebrity endorsers’ transgressions on associated brands. Drawing on research on moral reasoning, we posit that consumers are not always motivated to separate judgments of performance from judgments of morality (moral decoupling) or simply excuse a wrongdoer (moral rationalization). We propose that consumers also engage in moral coupling, a distinct moral reasoning process which allows consumers to integrate judgments of performance and judgments of morality. In three studies, we demonstrate that moral coupling is prevalent and has unique predictive utilities in explaining consumers’ evaluation of the transgressor (Studies 1 and 2). We also show that transgression type (performance related vs. performance unrelated) has a significant impact on consumers’ choice of moral reasoning strategy (Study 2). Finally, we demonstrate that consumers’ support for (or opposition toward) a brand endorsed by a transgressor is a direct function of moral reasoning choice (Study 3). Findings suggest that public figure’s immoral behavior and its spillover to an extended brand is contingent on consumers’ moral reasoning choices.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Accenture Sponsorship Update (2009, December 13). Retrieved from http://newsroom.accenture.com/article_display.cfm?article_id=4915 [Last Accessed January 8, 2015].

Badenhausen, K. (2013, June 5). Tiger Woods is back on top of the world’s highest-paid athletes. Forbes. Retrieved from http://www.forbes.com/sites/kurtbadenhausen/2013/06/05/tiger-woods-is-back-on-top-of-the-worlds-highest-paid-athletes/ [Last Accessed September 10, 2014].

Bandura, A. (1991). Social cognitive theory of moral thought and action. In W. M. Kurtines & J. L. Gewirtz (Eds.), Handbook of moral behavior and development: Theory, research, and applications (Vol. 1). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Bandura, A., Barbaranelli, C., Caprara, G. V., & Pastorelli, C. (1996). Mechanisms of moral disengagement in the exercise of moral agency. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71(2), 364–374.

Bargh, J. A. (1994). The four horsemen of automaticity: Awareness, efficiency, intention, and control in social cognition. In J. R. S. Wyer & T. K. Srull (Eds.), Handbook of social cognition (2nd ed., pp. 1–40). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Baumeister, R. F. (1998). The self. In D. T. Gilbert, S. T. Fiske, & G. Lindzey (Eds.), Handbook of social psychology (pp. 680–740). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Bhattacharjee, A., Berman, J. Z., & Reed, A. (2013). Tip of the hat, wag of the finger: How moral decoupling enables consumers to admire and admonish. Journal of Consumer Research, 39(6), 1167–1184.

Ditto, P. H., Pizarro, D. A., & Tannenbaum, D. (2009). Motivated moral reasoning. Psychology of Learning and Motivation, 50, 307–388.

ESPN News Services. (2009, December 14). Accenture cuts woods as sponsor. Retrieved from http://sports.espn.go.com/golf/news/story?id=4739219 [Last Accessed January 8, 2015].

Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Grappi, S., Romani, S., & Bagozzi, R. P. (2013). Consumer response to corporate irresponsible behavior: moral emotions and virtues. Journal of Business Research, 66(10), 1814–1821.

Greene, J., & Haidt, J. (2002). How (and where) does moral judgment work? Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 6(12), 517–523.

Gwinner, K. P. (1997). Building brand image through event sponsorship: The role of image transfer. Journal of Advertising, 28, 47–57.

Haidt, J. (2001). The emotional dog and its rational tail: A social intuitionist approach to moral judgment. Psychological Review, 108(4), 814–834.

Haidt, J. (2007). The new synthesis in moral psychology. Science, 316(5827), 998–1002.

Haugh, D. (2011, November 12). In Happy Valley, unhappy focus on Paterno. Chicago Tribune. Retrieved from http://articles.chicagotribune.com/2011-11-12/sports/ct-spt-1113-haugh-penn-state-scandal–20111113_1_joe-paterno-son-jay-paterno-joepa [Last Accessed January 8, 2015].

Hoffman, M. L. (1994). The contribution of empathy to justice and moral judgment. Reaching out: Caring, altruism, and prosocial behavior, 7, 161–194.

Horrow, R., & Swatek, K. (2009, December 10). Who benefits from Tiger Woods’ scandal? Bloomberg Businessweek. Retrieved from http://www.businessweek.com/lifestyle/content/dec2009/bw20091210_272903.htm.

Kalb, I. (2013, April 5). Why brands like Nike stuck with Tiger Woods through his scandal. Business Insider. Retrieved from http://www.businessinsider.com/tiger-woods-a-tale-of-two-images-2013-4 [Last Accessed January 8, 2015].

Klayman, B. (2009, December 14). Nike chairman stands by Tiger Woods: report. Reuters. Retrieved from http://www.reuters.com/article/2009/12/14/us-golf-woods-nike-idUSTRE5BD2PV20091214 [Last Accessed January 8, 2015].

Kunda, Z. (1990). The case for motivated reasoning. Psychological Bulletin, 108, 480–498.

MacKenzie, S. B., & Lutz, R. J. (1989). An empirical examination of the structural antecedents of attitude toward the ad in an advertising pretesting context. Journal of Marketing, 53, 48–65.

McCracken, G. (1989). Who is the celebrity endorser? Cultural foundations of the endorsement process. Journal of Consumer Research, 16(3), 310–321.

Mittal, B. (1995). A comparative analysis of four scales of consumer involvement. Psychology & Marketing, 12(7), 663–682.

Sassenberg, A. M., & Johnson-Morgan, M. (2010). Scandals, sports and sponsors: What impact do sport celebrity transgressions have on consumer’s perceptions of the celebrity’s brand image and the brand image of their sponsors? In the 8th Annual Sport Marketing Association Conference (SMA 2010) Proceedings (pp. 1–9).

Schwarz, N., & Clore, G. L. (2003). Mood as information: 20 years later. Psychological Inquiry, 14, 296–303.

Tsang, J. (2002). Moral rationalization and the integration of situational factors and psychological processes in immoral behavior. Review of General Psychology, 6(1), 25–50.

Vanhamme, J., & Grobben, B. (2009). Too good to be true!. The effectiveness of CSR history in countering negative publicity. Journal of Business Ethics, 85(2), 273–283.

Wismer, D. (2013, March 31). Tiger Woods: ‘Winning takes care of everything’ Forbes.com. Retrieved from http://www.forbes.com/sites/davidwismer/2013/03/31/tiger-woods-winning-takes-care-of-everything-and-other-quotes-of-the-week/ [Last Accessed October 28, 2014].

Yi, Y. (1990). The effects of contextual priming in print advertisements. Journal of Consumer Research, 17(2), 215–222.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1

Priming Statements Used in Study 1

[Moral Coupling condition]

As a society, we often fail to let our view of someone’s immoral actions affect our view of their value to society.

People who achieve great things should not be given a free pass if their personal actions are highly immoral.

It is important to take into account someone’s personal actions when assessing their job performance.

[Moral Decoupling condition; Bhattacharjee et al. 2013]

As a society, we are often too quick to let our view of someone’s immoral actions affect our view of their value to society.

Even if someone acts in a highly immoral manner, we should not let this affect our judgment of their great achievements.

It is inappropriate to take into account someone’s personal actions when assessing their job performance.

[Moral rationalization condition; Bandura et al. 1996]

As a society, we often fail to consider that small indiscretions are not as bad as some other horrible things that people do.

People should not always be at fault for immoral actions because situational pressures are often so high.

It is important to take into account that some immoral personal actions are okay because they really do not do much harm.

[Control condition]

As a society we often fail to consider the importance of having a sense of humor.

People should always be able to laugh at themselves and their actions.

It is important to not take everything too seriously when dealing with conflict.

Appendix 2

Scenario Used in Study 1

Imagine that a long-distance runner with outstanding winning records has captivated the public and the media for years. The athlete led the US Track & Field team to win the World Championship in Athletics in the 3,000 meter competition in 2011 and 2012. The athlete has also won the US Indoor Track & Field Championships in the 3,000 meter competition 5 times (in 2006, 2008, 2009, 2011, and 2012). Currently, the athlete is on a 4-year endorsement contract with a sports drink company.

Now imagine that the athlete is involved in a tax fraud case. The athlete is accused of scamming $650,000 in taxes in 2010–2012. The Internal Revenue Service (IRS) confirmed that the athlete failed to file multiple tax returns.

Appendix 3

Articles Used in Study 2 and Study 3

(Note. For study 3, only doping and financial fraud conditions were used.)

[General endorser information—constant in all conditions]

Ted Franklin is a 26-year-old long-distance runner on the US Olympic Track and Field team. He specializes in 3,000 meter competitions. Since he qualified for the USATF National Junior Olympic Track and Field Championships in 2002, he has won the USA Indoor Track and Field Championships in 3,000 meters competitions 5 times (in 2004, 2005, 2007, 2011, and 2012). Currently, he is on a 4-year-long endorsement contract with Coolpis™, an isotonic sports drink (or a carbonated soft drink) company, ending in 2014.

[Performance-related transgression condition—Doping]

(SI.com)

Posted: Monday April 15, 2013 9:22 AM; Updated: Monday April 15, 2013 12:19 PM (Associated Press)

The US Anti-Doping Agency announces that American national team member Ted Franklin has been banned for one year for doping. The ban annuls all his results since March 3, 2012. This means the 26-year-old Franklin will lose the gold medal he won for finishing first in the 3,000 meters at the 2012 USA Indoor Track and Field Championships. The USADA says tests showed an abnormal hemoglobin profile in his biological passport. Bans on the runner went into effect last Friday, February 1, 2013.

[Performance-unrelated transgression condition—Financial fraud]

(SI.com)

Posted: Monday April 15, 2013 9:22 AM; Updated: Monday April 15, 2013 12:19 PM (Associated Press)

Ted Franklin, 26-year-old Team USA long-distance runner, had been charged on 43 counts that included grand theft and false statements, according to court documents. Ted Franklin’s arrest warrant indicated that he accepted investments to his companies—TF Investments—without a license. An investigation of Ted Franklin’s accounts found he solicited large sums of money from investors, many of whom were over the age of 65, according to the arrest warrant. Investigators identified 28 people who invested with Franklin, the document says.

[Control condition: Hobby]

Ted Franklin, 26-year-old Team USA long-distance runner, seems to enjoy speed both on the track and the road. Unlike many athletes, Franklin owns a Piaggio Mp3 250 scooter. This model is a slanting three-wheeled scooter from a leading manufacturer of Italian motorbike market, Piaggio, which was first brought to market in 2006. Dissimilar to other scooters, this one has two wheels in front and the other at the back. Franklin owns a silver gray color scooter which he is often spotted riding.

Appendix 4

Article Used in Study 3

[Endorsement agreement information]

According to the LA Times, in January 2011 Coolpis™, a California based endurance enhancing drink company, announced that the company signed a contract with a long-distance runner, Ted Franklin, for a 4-year-long endorsement deal. While details of the contract are not disclosed to the public, the contract is known to include several conditions about advertising, media events, and so on.

About Coolpis™

Coolpis™ was found in 1992 as a family company in Porterville, California. The company has now become one of the most popular isotonic sports drinks on the West Coast in the US. They blend natural minerals to enhance consumers’ endurance during their sports activities. Coolpis™ is planning to extend their USA market to the Midwestern region in 2013 and the Southern region in 2014.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, J.S., Kwak, D.H. Consumers’ Responses to Public Figures’ Transgression: Moral Reasoning Strategies and Implications for Endorsed Brands. J Bus Ethics 137, 101–113 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2544-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2544-1