Abstract

We offer an analysis of the Greek and Italian future morphemes as epistemic modal operators. The main empirical motivation comes from the fact that future morphemes have systematic purely epistemic readings—not only in Greek and Italian, but also in Dutch, German, and English will. The existence of epistemic readings suggests that the future expressions quantify over epistemic, not metaphysical alternatives. We provide a unified analysis for epistemic and predictive readings as epistemic necessity, and the shift between the two is determined compositionally by the lower tense. Our account thus acknowledges a systematic interaction between modality and tense—but the future itself is a pure modal, not a mixed temporal/modal operator. We show that the modal base of the future is nonveridical, i.e. it includes p and ¬p worlds, parallel to epistemic modals such as must, and present arguments that future morphemes are a category that stands in between epistemic modals and predicates of personal taste. We identify, finally, a subclass of epistemic futures which are ratificational, and argue that will is a member of this class.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

We use FUT in this article to refer to expressions of future cross-linguistically, i.e. English will, Italian future morpheme (called futuro in the Italian grammars and literature), and Greek tha are FUT. We also use FUT to indicate the semantic function: FUT in various languages are realizations of the operator FUT in this sense. In the text, it is easy to see which sense is intended, but we also clarify when necessary. Likewise, we use MUST to refer to expressions of universal epistemic modality cross-linguistically, i.e. English must, Italian dovere and Greek prepi are MUST.

There is also a deterministic view: no unsettledness, just one future but we lack knowledge of it (Kissine 2008). That would render future morphemes tense operators. A mixed position could also be conceived, namely that future morphemes are ambiguous between modals and tenses. Such a view would stumble upon the fact that the temporal information correlates with lower tense, as we shall see. The possibility for modal and temporal ambiguity in any case should be dispreferred if an unambiguous analysis succeeds.

Pietrandrea (2005) uses the term ‘epistemic future’ for the first time for Italian future, but only for the epistemic use of the future. We thank Fabio Del Prete for bringing this point to our attention.

PERF stands for the semantic perfective. From now on, we use lower case to refer to the morphological components, and the capital letters for the semantic components.

Epistemic will with the past is odd, as indicated. We suggest why this is so in our discussion of will in Sect. 6.3.

See Giannakidou (2013a) for a formal connection between truth and existence.

See Bernardi (2002) for type-flexible definitions.

An anonymous reviewer points out adverbs such as evidently, clearly, unfortunately, which could be seen as veridical. But these are factive adverbs; our point above is that modal adverbs are nonveridical, not all adverbs.

We are grateful to the reviewers of this paper for prompting questions to this end.

The difference between knowledge and belief is not important for our purposes here, and in many other cases, e.g. for mood choice, it doesn’t matter—as verbs of knowledge and belief both select the indicative in many languages (Giannakidou and Mari 2016b). Mari (2016) however refines the typology of non-epistemic and fictional attitudes and shows that there is a systematic ambiguity between expressive-belief (the classical Hintikkean belief) and inquisitive-belief (the subjunctive trigger for languages in which mood is parametric to the status of p in the common ground). These differences do not matter here, and we only focus on the Hintikkean interpretation of belief.

See, however, Mari (2016) for the distinction between expressive and inquisitive belief, based on mood distribution in Italian.

We thank two anonymous reviewers for their insights that led to this discussion.

There are two exceptions to the Nonveridicality axiom, and both result in trivialization of modality. The first exception is the actuality entailment of an ability modal, in which case the modal is trivialized (see Mari forthcoming-a). The second is with aleithic modality, as in 1 + 1 must equal 2. Giannakidou and Mari (2016b) treat similar deductive contexts with must as involving aleithic modality, thus maintaining the nonveridicality axiom (and therefore the so-called weakness of the modal (Karttunen 1972)). With both aleithic modality and actuality entailment, the distinction between modal and non modal statement is lost.

It should be clear that our notation M(i) corresponds to the Kratzerian notation using set intersection \(\cap f_{epistemic}(w_{0},i)\), where this returns the set of worlds compatible with what it is known in \(w_{0}\) by i.

Since only those worlds are considered in which all the propositions in \(\mathcal{S}\) are true, the function Best determines a cut-off point.

We are grateful to the reviewers for their useful feedback on these central points.

The individual anchor for us is always a parameter of evaluation, and may (embedding with propositional attitudes) or may not be syntactically present (as in unembedded sentences).

Note that, for MacFarlane (2005) the future sentences cannot be assigned a truth value at the time of utterance. For us, it is assigned a truth value, it is true/false, parametrically to i.

An anonymous reviewer points to us the following excerpt from MacFarlane (2014).

Suppose you are standing in a coffee line, and you overhear Sally and George discussing a mutual acquaintance, Joe. SALLY says: Joe might be in China. I didn’t see him today. GEORGE: No, he can’t be in China. He doesn’t have his visa yet. SALLY: Oh, really? Then I guess I was wrong. It seems that George is contradicting Sally and rejecting her claim. It also seems that, having learned something from George, Sally concedes that she was wrong. Finally, it seems appropriate for her to retract her original claim, rather than continuing to stand by it. Think how odd it would be were she to respond: SALLY: Oh, really? # Still, I was right when I said ‘Joe might be in China,’ and I stand by my claim.

Extending the argument for epistemic English might to Italian and Greek future, we would claim that those who judge epistemic/future claims to be false when the prejacent is false are looking at the bare propositional content excluding the speaker index. Those who judge such claims to be true even when the prejacent is false are looking at thefinal truth value including the speaker index. For clarity we are glossing truth/falsity as truth i /falsity i to highlight those cases in which the speaker index is taken into account. We thank the reviewer for providing this material.

When the prejacent is stative (and the time of evaluation is not forward-shifted), the modal has an epistemic interpretation. According to Condoravdi (2002) the modal has a metaphysical interpretation in (95a).

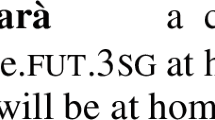

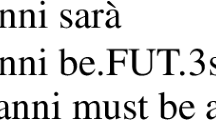

As often noted, forward-shifting is observed with statives too, e.g. as in ‘Domani sarà malato’ (Tomorrow he will be ill), see Giannakidou and Mari (2016b) for details.

Note that metaphysical modality also involves knowledge, just like any statement, including non-modalized ones. However, a metaphysical modal as in The Western underground orchid can grow here does not involve a non-veridical epistemic state. Just as the non-modalized version The Western underground orchid grows around here, it involves subjective veridicality (recall Sect. 3.2): the speaker knows that the conditions for having orchids growing here are met. This is subjective veridicality. On the other hand, the metaphysical modality is not implicative: it is not entailed that the orchid actually grows here (the modality is only compatible with orchid growing here). In our terms, metaphysical modality presupposes non-veridicality in the metaphysical space. It does not presuppose non-veridicality in the subjective space, which is the one targeted by future sentences and epistemic modals.

References

Abusch, Dorit. 2004. On the temporal composition of infinitives. In The syntax of time, eds. Jacqueline Guéron and Jacqueline Lecarme, 1–34. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Arregi, Karlos, and Peter Klecha. 2015. The morphosemantics of past tense. In North East Linguistic Society (NELS) 45, eds. Thuy Bui and Deniz Özyıldız, 53–66. Amherst: GLSA.

Asher, Nicholas, and Michael Morreau. 1995. What some generics mean. In The generic book, eds. Gregory Carlson and Francis Jeffry Pelletier, 224–237. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Aristotle. De Interpretatione Book IX. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Beaver, David I., and Jonathan Frazee. 2014. Semantics. In The handbook of computational linguistics, 2nd edn., ed. Ruslan Mitkov. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bernardi, Raffaella. 2002. Reasoning with polarity in categorial type logic. PhD diss., University of Utrecht.

Bertinetto, Paolo. 1979. Alcune Ipotesi sul nostro futuro (con alcune osservazioni su potere e dovere). Rivista di grammatica generativa 4: 77–138.

Bonomi, Andrea, and Fabio Del Prete. 2008. Evaluating future-tensed sentences in changing contexts. Ms., University of Milan.

Boogaart, Roni, and Radoslava Trnavac. 2011. Imperfective aspect and epistemic modality. In Cognitive approaches to tense, aspect and epistemic modality, eds. Adeline Patard and Frank Brisard, 217–248. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Broekhuis, Hans, and Henk Verkuyl. 2014. Binary tense and modality. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 32: 973–1009.

Cariani, Fabrizio. 2014. Predictions and modality. Ms., Northwestern University.

Cariani, Fabrizio, and Paolo Santorio. 2015. Selection function semantics for will. In 20th Amsterdam Colloquium, 80–89.

Chiou, Michael. 2014. What is the ‘future’ of Greek? Towards a pragmatic analysis. Research in Language 12. doi:10.1515/rela-2015-0004.

Cipria, Alicia, and Craige Roberts. 2000. Spanish imperfecto and pretérito: Truth conditions and Aktionsart effects in a situation semantics. Natural Language Semantics 8: 297–347.

Coates, Jennifer. 1983. The semantics of the modal auxiliaries. London: Croom Helm.

Comrie, Bernard. 1985. Tense. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Comrie, Bernard. 1976. Aspect. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Condoravdi, Cleo. 2002. Temporal interpretation of modals: Modals for the present and for the past. In The construction of meaning, eds. David I. Beaver, Luis D. Cassillas Martínez, Brady Z. Clark, and Stefan Kaufmann, 59–88. Stanford: CSLI.

Copley, Bridget. 2002. The semantics of the future. PhD diss., MIT.

Copley, Bridget. 2009. Temporal orientation in conditionals. In Time and modality, eds. Jacqueline Guéron and Jacqueline Lecarme, 59–77. Dordrecht: Springer.

Dahl, Östen. 1985. Tense and aspect systems. Oxford: Blackwell.

Dendale, Patrick. 2001. Le futur conjectural versus devoir épistémique: Différences de valeur et restrictions d’emploi. Le Français Moderne 69(1): 1–20.

Del Prete, Fabio. 2014. The interpretation of indefinites in future tense sentences: A novel argument for the modality of will? In Future Times, Future Tenses, eds. Mikhail Kissine, Philippe de Brabanter, and Saghie Sharifzadeh, 44–71. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dowty, David. 1979. Word meaning and Montague grammar. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic.

Enç, Murvet. 1996. Tense and modality. In Handbook of contemporary semantic theory, ed. Shalom Lappin, 345–358. Oxford: Blackwell.

Farkas, Donka F. 1992. On the semantics of subjunctive complements. In Romance languages and modern linguistic theory, ed. Paul Hirschbühler, 69–105. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Farkas, Donka F. 2002. Varieties of indefinites. Semantics and Linguistic Theory (SALT) 12: 59–83.

von Fintel, Kai, and Anthony Gillies. 2010. Must…stay… strong! Natural Language Semantics 18: 351–383.

Giannakidou, Anastasia. 1994. The semantic licensing of NPIs and the Modern Greek subjunctive. In Language and Cognition 4, Yearbook of the Research Group for Theoretical and Experimental Linguistics, eds. Ale de Boer, Helen de Hoop, and Henriëtte de Swart, 55–68. Groningen: University of Groningen.

Giannakidou, Anastasia. 1997. The landscape of polarity items. PhD diss., University of Groningen.

Giannakidou, Anastasia. 1998. Polarity sensitivity as (non)veridical dependency. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Giannakidou, Anastasia. 1999. Affective dependencies. Linguistics and Philosophy 22: 367–421.

Giannakidou, Anastasia. 2009. The dependency of the subjunctive revisited: Temporal semantics and polarity. Lingua 120: 1883–1908.

Giannakidou, Anastasia. 2012. The Greek future as an epistemic modal. In International Conference on Greek Linguistics (ICGL) 10. Komotini: University of Thrace.

Giannakidou, Anastasia. 2013a. Inquisitive assertions and nonveridicality. In The dynamic, inquisitive, and visionary life of ϕ, ?ϕ and possibly ϕ—A festschrift for Jeroen Groenendijk, Martin Stokhof and Frank Veltman, eds. Maria Aloni, Michael Franke, and Floris Roelofsen, 115–126.

Giannakidou, Anastasia. 2013b. (Non)veridicality, epistemic weakening, and event actualization: Evaluative subjunctive in relative clauses. In Nonveridicality and Evaluation: Theoretical, computational, and corpus approaches, eds. Radoslava Trnavac and Maite Taboada. Leiden: Brill.

Giannakidou, Anastasia. 2014a. The futurity of the present and the modality of the future: A commentary on Broekhuis and Verkuyl. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 32(3): 1011–1032.

Giannakidou, Anastasia. 2014b. The prospective as nonveridical: polarity items, speaker commitment, and projected truth. In The black book. Feestschrift for Frans Zwarts, eds. Dicky Gilberts and Jack Hoeksema, 101–124.

Giannakidou, Anastasia, and Alda Mari. 2012. Italian and Greek futures as epistemic operators. Chicago Linguistics Society (CLS) 48: 247–262.

Giannakidou, Anastasia, and Alda Mari. 2013a. The future of Greek and Italian: An evidential analysis. Sinn und Bedeutung 17: 255–270.

Giannakidou, Anastasia, and Alda Mari. 2013b. A two dimensional analysis of the future: Modal adverbs and speaker’s bias. In Amsterdam Colloquium 2013, 115–122.

Giannakidou, Anastasia, and Alda Mari. 2016a. Epistemic future and epistemic MUST: Non-veridicality, evidence and partial knowledge. In Mood, aspect and modality revisited, eds. Joanna Blaszczack, Anastasia Giannakidou, Dorota Klimek-Jankowska, and Krzysztof Migdalski. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Giannakidou, Anastasia, and Alda Mari. 2016b. Emotive predicates and the subjunctive: A flexible mood OT account based on (non)veridicality. In Sinn und Bedeutung 20, 288–305.

Giannakidou, Anastasia, and Frans Zwarts. 1999. Aspectual properties of temporal connectives. In Greek Linguistics ’97: 3rd International Conference on Greek Linguistics, ed. Amalia Mozer, 104–113. Athens: Ellinika Grammata.

Giorgi, Alessandra, and Fabio Pianesi. 1997. Tense and aspect: From semantics to morphosyntax. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hacquard, Valentine. 2006. Aspects of modality. PhD diss., MIT.

Hacquard, Valentine. 2010. On the event relativity of modal auxiliaries. Natural Language Semantics 18(1): 79–114.

Harris, Jesse A., and Christopher Potts. 2009. Perspective-shifting with appositives and expressives. Linguistics and Philosophy 32(6): 523–552.

Haegeman, Liliane. 1983. The semantics of will in present-day English: A unified account. Brussels: Royal Academy of Belgium.

Heim, Irene. 1994. Comments on Abusch’s theory of tense. Ms., MIT.

Hintikka, Jakko. 1962. Knowledge and belief. Cornell: Cornell University Press.

Holton, David, Peter Mackridge, and Irene Philippaki-Warburton. 1997. Greek: A comprehensive grammar of the modern language. London: Routledge.

Huddleston, Rodney, and Geoffrey Pullum. 2002. The Cambridge grammar of the English language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Iatridou, Sabine. 2010. The grammatical ingredients of counterfactuality. Linguistic Inquiry 31(2): 231–270.

Joseph, Brian, and Panayiotis Pappas. 2002. On some recent views concerning the development of the Greek future system. Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies 26: 247–273.

Karttunen, Lauri. 1972. Possible and must. In Syntax and Semantics, Vol. 1. Cambridge: Academic Press.

Kaufmann, Stefan. 2005. Conditional truth and future reference. Journal of Semantics 22(3): 231–280.

Kissine, Mikhail. 2008. From predictions to promises. Pragmatics and Cognition 16: 169–189.

Klecha, Peter. 2013. Diagnosing modality in predictive expressions. Journal of Semantics 31: 443–455.

Kratzer, Angelika. 1991. Modality. In Semantics: An international handbook of contemporary research, eds. Arnim von Stechow and Dieter Wunderlich, 639–650. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Kush, Dave. 2011. Height-relative determination of (non-root) modal flavor: Evidence from Hindi. Semantics and Linguistic Theory (SALT) 21: 413–425.

Laca, Brenda. On modal tenses and tensed modals. Ms., Université Paris 8 / CNRS.

Landman, Fred. 1992. The progressive. Natural Language Semantics 1: 1–32.

Lasersohn, Peter. 2005. Context dependence, disagreement, and predicates of personal taste. Linguistics and Philosophy 28: 643–686.

Lassiter, Dan. 2014. The weakness of must: In defense of a Mantra. In Semantics and Linguistic Theory (SALT) 24, 597–618.

Lederer, Herbert. 1969. Reference grammar of the German language. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

Lyons, John. 1977. Semantics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mari, Alda. 2005a. Sous-spécification et interprétation contextuelle. In Interpréter en contexte, eds. Francis Corblin and Claire Gardent, 81–106. Paris: Hermès.

Mari, Alda. 2005b. Intensional and epistemic wholes. In The compositionality of meaning and content, eds. Markus Werning, Edouard Machery, and Gerhard Schurz. Frankfurt: Ontos Verlag.

Mari, Alda. 2009a. Disambiguating the Italian future. In Generative Lexicon, 209–216.

Mari, Alda. 2009b. The future: How to derive the temporal interpretation. In JSM 2009, Paris: University Paris-Diderot.

Mari, Alda. 2009c. Future, judges and normalcy conditions. Selected talk at Chronos 10, Austin, Texas. Available at https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/ijn_00354462/. Accessed 4 April 2017.

Mari, Alda. 2014. Each other, asymmetry and reasonable futures. Journal of Semantics 31(2): 209–261.

Mari, Alda. 2015a. Modalités et Temps. Bern: Peter Lang Ag.

Mari, Alda. 2015b. French future: Exploring the future ratification hypothesis. Journal of French Language Studies 26(3): 353–378.

Mari, Alda. 2016. Assertability conditions of epistemic (and fictional) attitudes and mood variation. Semantics and Linguistic Theory (SALT) 26: 61–81.

Mari, Alda. forthcoming-a. Actuality entailments: When the modality is in the presupposition. In Lecture notes in computer science, Dordrecht: Springer.

Mari, Alda. forthcoming-b. The French future: Evidentiality and incremental information. In Empirical approaches to evidentiality, eds. Ad Foolen, Helen de Hoop, and Gijs Mulder. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Markopoulos, Theodore. 2009. The future in Greek: From ancient to medieval. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

de Marneffe, Marie-Catherine, Christopher Manning, and Christopher Potts. 2012. Did it happen? The pragmatic complexity of veridicality assessment. Computational Linguistics 38: 300–333.

Matthewson, Lisa. 2012. On the (non)-future orientation of modals. In Sinn und Bedeutung, Vol. 16, 431–446.

MacFarlane, John. 2005. Future contingents and relative truth. The Philosophical Quarterly 53: 321–336.

MacFarlane, John. 2014. Assessment sensitivity: Relative truth and its applications. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

McCawley, James D. 1988. The syntactic phenomena of English. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Montague, Richard. 1969. On the nature of certain philosophical entities. Monist 53: 161–194.

Partee, Barbara. 1984. Nominal and temporal anaphora. Linguistics and Philosophy 7: 243–286.

Palmer, Frank. 1987. Mood and modality. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Papafragou, Anna. 2006. Epistemic modality and truth conditions. Lingua 116: 1688–1702.

Pietrandrea, Paola. 2005. Epistemic modality: Functional properties and the Italian system. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Philippaki-Warburton, Irene. 1998. Functional categories and Modern Greek syntax. The Linguistic Review 15: 159–186.

Portner, Paul. 1998. The progressive in modal semantics. Language 74(4): 760–787.

Portner, Paul. 2009. Modality. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Portner, Paul, and Aynat Rubinstein. 2012. Mood and contextual commitment. In Semantics and Linguistic Theory (SALT) 22, 461–487.

Prior, Arthur. 1967. Time and modality. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Rocci, Andrea. 2000. L’interprétation épistémique du futur en Italien et en Français: une analyse procédurale. Cahiers de Linguistique Française 22: 241–274.

Roussou, Anna. 2000. On the left periphery; modal particles and complementizers. Journal of Greek Linguistics 1: 63–93.

de Saussure, Louis, and Patrick Morency. 2011. A cognitive-pragmatic view of the French epistemic future. Journal of French Language Studies 22: 207–223.

Smith, Carlota. 1991. The parameter of aspect. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Smirnova, Anastasia. 2013. Evidentiality in Bulgarian. Journal of Semantics 30(4): 1–74.

Squartini, Marco. 2004. Disentangling evidentiality and epistemic modality in Romance. Lingua 114: 873–895.

Stephenson, Tamina. 2007. Judge dependence, epistemic modals, and predicates of personal taste. Linguistics and Philosophy 30(4): 487–525.

de Swart, Henriëtte. 2007. A cross-linguistic discourse analysis of the perfect. Journal of Pragmatics 39: 2273–2307.

Tasmowski, Liliane, and Patrick Dendale. 1998. Must/will and doit/futur simple as epistemic modal markers. Semantic value and restrictions of use. In English as a human language, ed. John van der Auwera, 325–336. Munich: Lincom Europa.

Thomason, Richmond. 1984. Combination of tense and modality. In Handbook of philosophical logic: Extensions of classical logic, eds. Dov Gabbay and Franz Guenthner, 135–165. Dordrecht: Reidel.

Todd, Patrick. 2016. Future contingents are all false! On behalf of a Russellian open future. Mind 125(499): 775–798.

Tsangalidis, Anastasios. 1998. Will and tha: A comparative study of the category future. Thessaloniki: University Studio Press.

Veltman, Frank. 2006. Defaults in update semantics. Journal of Philosophical Logic 25: 221–261.

Verkuyl, Henk. 2011. Tense, aspect and temporal representation, 2nd edn. In Handbook of Logic and Language, eds. Johan van Benthem and Alice ter Meulen, 975–988. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Zimmermann, Malte. 2011. Discourse particles. In Semantics: An international handbook of meaning (HSK 33.2), eds. Claudia Maienborn, Klaus von Heusinger, and Paul Portner, 2011–2038. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Zwarts, Frans. 1995. Nonveridical contexts. Linguistic Analysis 25(3–4): 286–312.

Acknowledgements

We have been working on various aspects of the material presented in this paper for quiet a while, and have benefitted from presenting it in a number of venues (the Amsterdam Colloquium, colloquia at the University of Groningen, University of Leiden, Free University of Brussels, Princeton University, École Normale Superieure, Northwestern University, the 2015 ESSLLI Summer-school in Barcelona, and the Linguistics and Philosophy workshop at the University of Chicago). We are grateful to the audiences of these events for their feedback. We want to thank in particular Fabrizio Cariani, Bridget Copley, Jack Hoeksema, Chris Kennedy, Mikhail Kissine, Frank Veltman, and Malte Willer for their more involved comments. A special thanks is due to the three NLLT reviewers for their careful engagement with our material, and their many useful insights and encouragement. Finally, a big thank you to Henriëtte de Swart, who guided us through the process as handling editor and whose comments and suggestions lead to considerable improvements in both content and form. As for Alda Mari, this research was funded by ANR-10- LABX-0087 IEC and ANR-10-IDEX-0001-02 PSL. This paper was written during her stay at the University of Chicago in 2014–2016. Alda Mari also gratefully thanks the CNRS-SMI 2015. The order of the authors is alphabetical.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Giannakidou, A., Mari, A. A unified analysis of the future as epistemic modality. Nat Lang Linguist Theory 36, 85–129 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-017-9366-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-017-9366-z