Abstract

This paper assesses leading Japanese philosophical thought since the onset of Japan’s modernity: namely, from the Meiji Restoration (1868) onwards. It argues that there are lessons of global value for AI ethics to be found from examining leading Japanese philosophers of modernity and ethics (Yukichi Fukuzawa, Nishida Kitaro, Nishi Amane, and Watsuji Tetsurō), each of whom engaged closely with Western philosophical traditions. Turning to these philosophers allows us to advance from what are broadly individualistically and Western-oriented ethical debates regarding emergent technologies that function in relation to AI, by introducing notions of community, wholeness, sincerity, and heart. With reference to AI that pertains to profile, judge, learn, and interact with human emotion (emotional AI), this paper contends that (a) Japan itself may internally make better use of historic indigenous ethical thought, especially as it applies to question of data and relationships with technology; but also (b) that externally Western and global ethical discussion regarding emerging technologies will find valuable insights from Japan. The paper concludes by distilling from Japanese philosophers of modernity four ethical suggestions, or spices, in relation to emerging technological contexts for Japan’s national AI policies and international fora, such as standards development and global AI ethics policymaking.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Focusing on Japan, this paper examines what leading Japanese philosophers of modernity have to offer academic and policy-based ethical understanding of artificial intelligence (AI), here paying particular attention to ‘emotional AI’ that involves discerning facial expressions, gaze direction, gestures, voices, and other biometrics. This is a narrow form of AI, reliant on diverse sensors and actuators, and (typically, but not always) supervised machine learning, along with a range of neural network types (including convolutional, region, and recurrent) depending on what is being sensed and in what context (Altenberger & Lenz, 2018; Lipton et al., 2015; Ren et al., 2015). These systems may be used at macro- and micro-scales, such as core infrastructure in surveillance-oriented “smart city” developments, and in domestic and worn (and less frequently, embedded) contexts. Growing in popularity across the world, use cases for emotional AI include (but are not limited to) augmentation of facial recognition and surveillance of cities and core infrastructure (such as transport hubs, schools, workplaces, and interactive out-of-home advertising); private spaces open to the public (such as retail and sports stadia); and more private experiences (such as enhanced interaction with devices and media content; synthetic personalities and embodied AI assistants; toys and entertainment; wellbeing apps and hardware; in-car analytics; and companionship in elderly care homes). In brief, wherever there is perceived value in gauging and interacting with human emotion, there is organisational interest in deploying emotional AI.

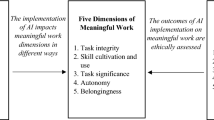

Arguing there are lessons of global social value to be found in Japanese ethical thought from its traditional beliefs and their modern articulations, particularly because leading thinkers of the modern period engaged so closely with a variety of Western philosophical traditions, the paper contends that (a) Japan itself may internally make better use of its historic indigenous ethical thought, especially as it applies to question of data and relationships with technology; but also (b) that externally, Western and global ethical discussion regarding emerging technologies will find valuable insights from Japanese philosophical notions (or “Spices”) of community, wholeness, sincerity, and heart. Applying these Spices to emotional AI assists with de-Westernisation of the ethical conundrums arising from emotional AI, including the need to consider civic as well as personal concerns about usage in public spaces; the objectification and decontextualization arising from machine learning of emotions; avoidance of presumption of intimacy with others; and the complexity of interactions with synthetic personalities as affect-based systems grow more sophisticated.

The paper has three key components: (1) it outlines international and national influences on modern Japanese AI ethics policy; (2) it investigates the hybridisation of dominant Japanese ethical beliefs with Western discourses during and after the Meiji Restoration (1868) that initiated Japan’s modernity; and (3) it generates global ethical lessons (or “Spices”) in relation to emerging technological contexts for Japan’s national AI policies and international fora, such as standards development and global AI ethics policymaking. For academic thought, the paper amplifies and advances arguments regarding the value of non-Western philosophies in assessing ethics and technology. Distilled into the four Spices, the paper provides practical ethical recommendations for policymakers in Japan and international governance bodies. Undoubtedly, given space for investigation into a fuller range of Japanese philosophers, more spices might be found. Yet, like Japanese food spicing that is careful and thought-out, the four selected have wide applicability.

2 Influences on Japan’s AI Ethics Policies

The Japanese government has long been interested in guiding and funding AI development, not least Japan’s Super City Initiative, involving a bill passed in 2020 by Japan’s Diet (its national legislature) for so-called super cities. In practice, this meant local governments are selected by the central government to work with private technology firms to create plans for their own smart city, a point amplified by Japan’s Cabinet Office that ‘is promoting the Super City Initiative that realizes the ideal future society in advance through cutting‐edge technology and bold deregulation in the Fourth Industrial Revolution’ (Government of Japan, 2020). Other notable policy initiatives include the Humanoid Robotics Project in 1998, funded by Japan’s Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry (METI) and New Energy and Industrial Technology Development Organization (NEDO). Prime Minister Abe’s Innovation 25 programme that began in 2007 is also noteworthy, given its ambition to reinvent Japanese society by 2025 by reversing declining birth rate and accommodating an aging population. Abe’s subsequent programme, Society 5.0, similarly envisions an ‘inclusive socio-economic system’, being based on big data analytics, artificial intelligence (AI), the Internet of Things, and robotics technologies, all intersecting with emotional AI.

There are many influences on contemporary AI ethics policy in Japan, of a western liberal and arguably neo-liberal tenor. These influences include international bodies, such as the World Economic Forum (WEF) and Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), all based on progress through liberal economic trade. Others are international in the form of technology standards groups, such as the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) that have expanded their interests to encompass ethical questions regarding the design and implementation of automated technologies. As will be developed in this paper, there are notable national and regional influences on AI ethics policy in Japan, not least by the EU, UK, USA, and Canada.

Ethical buzzwords employed by intra-Japanese agencies are also familiar, being arguably Western and liberal in flavour. For example, Japan’s Council for Artificial Intelligence Technology Strategy, published by the Japan Cabinet Office, advocates three core values of (1) dignity, (2) diversity and inclusion, and (3) sustainability (Cabinet Office, 2019). Japan’s initiatives recognise and converge with OECD and UNESCO international policy conversation on AI ethics (Expert Group on Architecture for AI Principles to be Practiced, 2021). Like Europe and most other regions, Japan seeks to balance pro-social implementation of AI with allowing businesses to innovate with AI-related technologies. To this end, Japan’s Expert Group report draws extensively on reports from the UK government, EU, USA, and international groups such as IEEE (especially its P7000 series of standards). Similarly, Japan’s Cabinet Office draft of the Social Principles of Human-centric AI notes that as AI principles are being discussed in many countries, organisations, and companies, ‘it is important to build an international consensus through open discussions as soon as possible and to share it internationally as a non-regulatory and non-binding framework’ (Cabinet Office, 2019: 10). Yet, Japan’s current policies are somewhat conventional, drawing upon and replicating other global content to allow Japan access to global markets and to help generate safe and socially valuable services. For instance, Japan’s alignment and adequacy with leading data protection regimes, such as the EU (Japan is a ‘third country’ under the EU’s data protection rules), means that personal data can legally move between the EU and Japan. Notably, the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation may be characterised as what Daly (2021) argues to be ‘regulatory capitalism’, simultaneously a way of encouraging neo-liberal norms and constraining it where it is not desirable for the EU’s single market. At heart, EU AI and data protection entails (among other values) statements of respect for human dignity, private life, self-determination, and protection of personal data (European Commission, 2021: §3.5, 11), a liberal worldview, whose principles would benefit from Japanese and hybrid thought as they apply to AI ethics and emotional AI applications.

Of themselves, the ideas of dignity, diversity, inclusion, and sustainability, found in Japan’s Council for Artificial Intelligence Technology Strategy, will be familiar to Western readers of Philosophy & Technology. More novel are the questions of (a) where is Japan’s own normative contribution and, (b) when identified, what might this add to serious global conversation (rather than that led by public relations) about ethics and technology? The absence of Japan’s own normative contribution, especially to global debate, is evident in the discussion by an expert in Europe and Japan data protection adequacy, Hiroshi Miyashita. Miyashita (2021) discusses the application of the Council of Europe’s Convention 108 + , its emphasis on human dignity, and that an individual should not be treated as a mere object. Importantly, Miyashita argues that ‘If European data protection laws are attached to the dignitarian philosophy, there is no such novel philosophy in Japan and probably not in most Asian countries’ (2021: 7). For Miyashita, ‘European human dignity has been incorporated into Japan with the addition of Japanese spices’ (ibid), not least through emphasis on the principle of respect.

There is a political and industrial dimension to such importing (and adaptation) of European normativity. If there is dissonance between the language employed in Japan’s AI ethics policies and normative context by those being asked to install this in their designs and technologies, there is a risk that it will be seen solely through the prism of compliance, rather than something more moral and pro-social. Murata (2019) for example sees the tendency for data protection to be framed as pro-economy law rather than pro-rights law. The minimal presence of local belief discourses may lower the chance of Japanese societal buy-in of global work on AI and technology ethics, for example, in terms of business culture, technology design, data protection enforcement, or use of new technologies in urban contexts. Indeed, Robertson (2018: 127) observes that while human rights are formally adhered to, the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs pays lip service to the Universal Declaration on Human Rights, and that they are regarded ‘by the state as pertaining to the universe outside of Japan’. Yet, with better recognition of the ethical universe within Japan, there is an opportunity to include lessons from Japan in global work on how to design, deploy and govern technologies that have consequences for human life. Indeed, a range of studies point out that differences between regional philosophical traditions lead to value differences on matters such as data privacy, not least due to questions of cultural differences (ÓhÉigeartaigh et al., 2020). It is to Japan’s different dominant belief systems and ethical practices that this paper now turns.

3 Belief Systems and Practices

Unlike the West where people mostly identify with one religion (such as Christianity), if they are at all religious, Japanese people tend towards syncretic views where religious beliefs are blended and personalised. A 2018 survey by the Government of Japan’s Agency for Culture Affairs found that 69.0 percent of the population practices Shintoism (Japan’s national religion); 66.7 percent Buddhism; 1.5 percent Christianity, and 6.2 percent other religions (Agency for Culture Affairs, 2019). To these, Confucianism can be added, although it is a philosophy of life rather than religion. Tracing of syncretism between these systems is complex work, far beyond the remit of this paper, but it is noteworthy that syncretism of the systems themselves began before dominant religions arrived in Japan, with expert scholarship for example being divided on whether Shinto (widely understood as Japan’s indigenous religion) is an extension of Buddhism, even finding historical evidence that Shinto was originally another term for Taoism in China (Toshio et al., 1981). Similarly, before Confucianism reached Japan, there had already been complementarity and mutual harmony between Buddhism and Confucianism in China (Vermeersch, 2020), with Confucianism then overlapping with Japanese Buddhism on arriving in Japan (Suzuki, 1959). Thus, while this paper cannot adequately address the intricacies of the syncretisation of Shintoism, Confucianism, Buddhism, and other influential outlooks such as Daoism, it should be recognised that there is great historical complexity regarding internal religious change, mutual influence, ability to maintain coherence of identity in diverse political regimes, and geopolitical change.

Beyond syncretisation, Lennerfors and Murata (2019) remind us that philosophy was a term imported into Japan around the Meiji era, meaning that pre-existing ethical theory should be interpreted through ‘historical records, legal codes, myths, religious books, narratives, poems, plays and so on since the early eighth century’ (2019: 8). Lennerfors and Murata (2019) also point to Masahide Satō and Watsuji Tetsurō as having done a great deal of the historical work in this regard. Certainly, ethics was lived and practiced but, arguably, it was not abstracted and systematised.

Today, Japan does not have one ethical system or outlook, which means that attempts to label and essentialise Japanese ethical and spiritual values are oversimplistic. Nevertheless, religion and belief matter, and it is notable that ‘the oldest past is still present, side by side with the newest forms of modern civilization’ (Nishida, 2003 [1958]: 57). As any resident or visitor of Japan will know, micro-Shinto shrines sit alongside (and within) the high modern architecture of Tokyo’s business district. Justice cannot be done to the complex histories and inter-relationships of these outlooks, but for introductory purposes, Shinto is based on reverence for nature, simplicity, completeness, unity, the natural sacredness of Japan itself, deep respect for ancestors, and spirits in the form of kami—that may be of places, natural forces, or things (Hardacre, 2017). Famously, Shinto also attributes living souls to plants, natural phenomena, and everyday objects, hence international interest in Japan’s relationship with technology and robots (Kitano, 2007). While this animism has been critiqued on grounds that it legitimates deceptive use of technology, this paper will argue that sensitivity to the blurring of objects and subjects is of ethical value in Spice 4 and emergent human-AI relations (sensitivity). Quite different from Japan’s native Shinto, there are reasons why Confucianism was well-received in Japan. This is due in part to its prescriptive behaviour, but also because it resonated with Shinto’s belief in showing respect for ancestors, care and honouring of parents and family, and emphasis on ritual and harmony. Factors of order and hierarchy certainly exist, but mention should also be made of its anthropocosmic outlook (Tucker, 1998) that removes human-kind’s sovereign status as the centre of existence, as this will recur in several of the four Spices later in this paper. Whereas Confucianism is based on social harmony and the public good, and Shinto on Kami and vitalism, Buddhism is preoccupied with impermanence and self-realisation (Mitchell & Jacoby, 2014). Having arrived in the form of Mahayana Buddhism from Korea in the early to mid-sixth century (Murata, 2019), this developed into Zen Buddhism. With later implication for Spice 2, this values intuition and suggestive expression (rather than objectivity and explicitness). As with Shinto and Confucianism, this Zen Buddhism appeals to larger non-human “wholes,” effectively dethroning humans in favour of an ecological view that accepts that various modes of existence are fused together.

4 Hybridity and the Japanese Modernity

Having very briefly introduced dominant Japanese ethical beliefs and practices, this paper now investigates their hybridisation with Western discourses that, in turn, initiated Japan’s modernity. Japan’s initial experiences with modernity are inextricable from the Meiji Restoration (1868), a period of profound social change that involved high engagement with the West and importation of influential liberal ethical thought. Yet, as will be developed, it also involved engagement with philosophies other than political philosophy. Here, Japanese philosophers such as Yukichi Fukuzawa, Nishida Kitaro, Nishi Amane, and Watsuji Tetsurō,Footnote 1 among others, built philosophical bridges between the West and Japan, drawing upon, and arguably extending, the work of Germanic philosophers (such as Kant, Herder, Hegel, Nietzsche, and Heidegger), and several phenomenologists and pragmatists. Indeed, Japanese philosophers Tanabe Hajime, Kuki Shūzō, and Miki Kiyoshi made trips to study with philosophers such as Heidegger (Lennerfors & Murata, 2019). The interest in German philosophy is due in large part to Japan’s interest in Germany’s rapid modernisation, but also fertile spiritual overlaps with older traditions present in Japan. This engagement involved both praise and criticism, but also a hybridising with longstanding philosophies of Shintoism, Buddhism, and Confucianism.

4.1 Modernity, Liberalism, and the Meiji Restoration: Japanese Sprit, Western Technology

Japan’s Meiji Restoration (1868) saw Japan modernise and industrialise quickly to respond to US and foreign advancements. This reconsidered not only physical and military strength, but also societal and intellectual orientation. Broadly a rejection of Tokugawa feudalism (1603–1868) and its period of Confucian dominance, we should be sensitive to the fact that there existed internal criticism of Tokugawa Confucian thought (Zhu Xi’s Confucianism). Strains included Ancient Learning or kogaku, Native Learning or kokugaku, and the Dutch Learning or rangaku. These are significant because of ongoing reinterpretation of Confucian thought in context of changing social realities, early engagement with systematised Western philosophies, philosophical allowance of scientific (materialist) worldviews and methods, but most importantly the initiation of the transition to the modern nation-based Japanese society in the Meiji period. This includes separation of the private sphere from the political, representing a step in the formation of the so-called modern individual (Culiberg, 2015). The Meiji Restoration itself was a period of social transition to one that recognised Western liberal prowess, yet also sought to maintain high national values. Drawing from Europe and the USA, Japan adopted technologies, business methods, military techniques, education, agricultural techniques, and economic governance ideas. In addition to engaging with secular, scientific, technological, industrial, and cultural developments from the West, there was a high level of engagement with Western philosophies. This is significant because this engagement was not detached from Japan’s rapid societal change. Instead, leading thinkers and philosophers were directly connected to policy figures initiating and leading societal change. This involved embracing Western concepts such as Shakai (society), Tetsugaku, (philosophy), Risei (the reason), and Kagaku (science), with indigenous terms augmented by Western concepts, such as Gijyutsu (technology), Shizen (nature), and Rinri (ethics).

The intention of the Meiji Constitution was not an emulation of the West, but to learn and surpass it and, under the aegis of wakon yōsai (Japanese spirit, Western technology), articulate a liberal modernity independent of the West. Undergoing the Meiji Restoration, the transformation of Japan was viewed as a social experiment that, if successful, would reveal the universality of the principles of values of democratization and economic liberalism. After all, if a principle is universal, it cannot belong to the West. In a paeon to democracy, liberalism, education, technology, and progress, Yukichi Fukuzawa opens his An Encouragement of Learning with ‘Heaven, it is said, does not create one person above or below another,’ that ‘we are all equal and there is not a discussion between high and low’ and that we can satisfy our daily needs through our own work ‘as long as we do not infringe upon the rights of others’ (2012 [1872–6]: 3).

Fukuzawa is stinging in his critique of Confucian dominance, stating it as a degenerate influence and ‘that Chinese philosophy as the root of education was responsible for our obvious shortcomings’ (2007 [1893]: 215). Also, for Fukuzawa, until number and reason were embraced, ‘Japan could not assert herself among the great nations of the world’ (ibid). Fukuzawa also takes aim at Shintoism, or the attribution of a nature or soul that animates an object, due to a view of the natural world that sees it as abounding with the spirits of the gods (kami-gami). Were Fukuzawa solely an academic philosopher, the embracing of liberal beliefs might not be that significant. However, as a public figure with direct influence on policymaking, Fukuzawa was a central figure in Japan’s modernisation.

Nishi Amane was one of the first scholars to be sent abroad (in the 1860s) to study Western social sciences (Havens, 1970), returning with Auguste Comte’s positivism and John. S. Mill’s accounts of utilitarianism. Nishi’s significance is underlined by Havens (1970), who remarks that Nishi is ‘commonly regarded as the father of modern Japanese philosophy’ (1970: 218). Keimo (enlightened) scholars, of which Nishi was one, were an intelligentsia that sought to study, translate, and import Western philosophies, especially political philosophies and concepts of individual rights and obligations, and natural and international law. Despite being steeped in Sung Confucianism, Nishi took great interest in Western principles of economics, social theory, philosophy, and countries such as the US and England [sic] that ruled by popular will (Nishi, cited by Havens, 1970: 44). Also noteworthy, given this paper’s earlier international policy discussion, is Nishi’s embrace of justice, fairness, freedom, and equal rights. What Nishi cites as English ideas were especially influential given its origination of economic liberalism (Adam Smith was of course Scottish). Although high regard of the English would be severely tested by English opium trading (and diplomacy through military and economic strength), Japanese scholars valued freedom, natural law (rights born from nature), ethical progress, universal ethical principles, and the innate wrongness of trading in freedom.

For a paper about ethics and emergent technology, this matters because it was in these few years (the late 1860s and 1870s) that seeds were sown in Japan for ethical principles familiar to the West and modern data protection experts. These include the idea ‘that self-awareness of personal rights must accompany the technological and institutional revolution that was taking place’ in the 1870s (Havens, 1970: 81). This transplanting was not immediate because equality butted against the social hierarchy models of the Tokugawa era, the period before the Meiji Restoration. Yet, Mill’s On Liberty (especially notable for modern privacy and data protection scholars), Representative Government, and Principles of Political Economy were translated into Japanese by 1875, reappearing in many other collections by the end of the century (Havens, 1970: 142). However, Mill’s popularity might also be explained in part by utilitarianism being a social rather than individualist philosophy, thus its principles not being entirely alien to Confucianism. However, although Western and liberal ideas were influential, they were certainly not universal in appeal to Japanese people. For instance, during the Meiji period, although there was respect for the UK’s achievements, contemporary Nihonjinron writing (the genre of writing focused on Japanese identity) lamented the dark, polluted, industrial cities of England, commercialism, the impact of these on Japanese values, how to confront modernity, and what progress looks like when modernity is balanced with Japanese ‘superiority’ (Goto-Jones, 2009: 61).

5 Community Ethics

Given the political, intellectual, and technological exchanges with the West, the 1800s engendered fertile hybridisation between longstanding Japanese belief systems and Western thought. In critical dialogue with Western individualism, post-Meiji thought often re-stated the value of community-based ethics. For example, Watsuji Tetsurō (1996 [1937]) sought a modern society based on inter-connections between people and a somewhat ecological view where ethics and values grow from connected contexts. Indeed, very relevant to today, Watsuji (1961) wrote directly about climate and humankind, and the need to de-centre ‘man’ [sic] from human existence, to better recognise the role of environments. Certainly, connected contexts mean groups of people, and human-made infrastructure that connects people (such as transport and media), but its significance is broader. Antagonistic to the West, Watsuji argued that ethics has been misconceived as a problem of individual consciousness and isolated egos. Ethics for Watsuji, are found in the ‘in-betweenness’ of people through communitarian interconnectedness. Later to be argued as the first of the four Spices (community), this is a fundamental point: ethics for Watsuji, a leading Japanese philosopher, are primarily about connections and context, not the self and egoism.

While conservative, there is also a deep pragmatism in its contextualism and social relativism. Values are neither found nor forever cast but grow from the character of given collectives, which in Lennerfors’ (2019) reading of Watsuji are milieu inextricable from technologies (with transport being a practical point of discussion for Watsuji). Today, the growth and creative dynamics of Confucianism are noted by Wong (2012) who points out that harmony and agreement mean different things in Confucianism. Agreement leads to mutual reinforcement, rather than growth, with the complementarity of cooking and music being useful analogies to counter similarity and agreement. As an ongoing dynamic process, harmony entails ongoing negotiation and adjustment between individuals and their community (Li, 2006; Wong, 2012). This is a curious point of ethical overlap between pragmatism and the Confucian-inspired Watsuji that are both sceptical that abstract normativity may provide adequate guidance to the complexities of any given societal formation. Importantly too, this social and contextual view of ethics means that both the state and its legal structures are not the arbiters of ethics. This is because, for Watsuji, ethics must be of the community, its shared history and hopes for the future, and an expression of these. This dialectic is expressed in ningen that Watsuji states is neither society nor the individual human beings living within it, but ‘the interconnection of acts,’ and the individual ‘that acts through these connections’ (ibid: 19).

Watsuji sought to bridge Japanese and Western thought, in part by seeking latent collectivist truths in Western philosophy. For example, on Kant’s writing about subjectivity, empirical idealism (that all we know immediately is the existence of our own minds and our temporally ordered mental states), and the noumenal (that which exists independent of human sensing), Watsuji argues that in this dualism the ‘individualistic/holistic structure of ningen was already imperceptibly grasped by Kant’ (ibid: 32). This is a creative interpretation, given Kant’s (1983 [1793]) accounts of freedom, individualism, autonomy, and the categorical imperative, where a person uses reasons to arrive at principles that a person believes to be objective for all. Critique of individualism continues in Watsuji’s reading of phenomenology, individual moral consciousness, Heidegger, and the Cartesian ego, with Watsuji problematising the beginning of inquiry from individual consciousness itself. Refuting individual consciousness as the basis of ethics he urges appreciation of in-betweenness as that which orients and connects people.

There are, then, important practicalities for the stereotypes of Western individualism and Japanese (or worse, Eastern) collectivism. This must be rejected, because Watsuji does not argue for community-determinism, although in accounting for the necessary contradiction in ningen in relation to Western phenomenology and liberal thought, he certainly takes shots at individualism. What is key and unique is that Western moral philosophy has, for the most part, assumed that people are individuals who go about setting up moral communities, whereas for Watsuji we are both social and individual in the embrace of a necessary contradiction. This might seem obvious in that “Of course ethics is about groups, connections, co-emergent behaviour, and context,” but this is not how dominant Western liberal normativity works. Rather, it typically champions individual moral choices, freedom, autonomy, and self-determination (all assuming no harm to others). While not a polar difference, as Watsuji sees the social and the individual, the community-based view of ethics is different from the more familiar liberal outlook. As to why this matters for a paper about ethics, governance, and emergent technologies, we might recollect that governance of data typically rests on the premise of personal data and self-determination. Addressed later, how are data ethics affected if a community-based perspective is also seen as valuable, one that admits that connections and contexts play a key role in determining what exists for individuals?

6 Modernity of a Buddhist Sort

Keeping in mind that this paper first explained the importation of liberal political and individualist philosophies, and then considered Confucian-inspired community-based reactions to these, we now turn to a Buddhist-inspired account. Nishida Kitarō rejects the suggestion that modernity is a Western experience, with his self-posed task being to re-articulate tradition in relation to emergent science and technology, and to articulate an understanding of modernity that does not originate from the West. The context in which Nishida wrote is important because he is a philosopher with a deep appreciation of Buddhism, yet also writing in the context of rapid technological development. In essence, he facilitated a rapprochement between Buddhism and modernity. For clarity, Nishida’s is not an updating of Buddhism in the context of modernity, but something else, a de-Westernising of modernity, to articulate the transformative energies of modernity in the context of Japanese belief, the timelessness of Buddhism, and connectedness with Japan’s cultural and spiritual unfolding. The significance of his work is such in Japan that Nishida’s book, Intelligibility and the Philosophy of Nothingness, was translated in 1958 by The International Philosophical Research Association of Japan as a means of bridging understanding between Japan and the West. In short, Nishida acts as a two-way bridge between influential Western philosophical thought and key parts of Japanese ways of being. For example, Nishida (2003 [1958]: 16) remarks that Heidegger’s (2011 [1962]) work on Being is familiar to not just him, but other Japanese thinkers. Indeed, the Kyoto School that Nishida founded would go on to have extensive engagement with Heidegger, both in-person and through his diverse output (Carter, 2013).

6.1 “Wholes” and Dynamic Cosmologies

Nishida’s translator, Robert Schinzinger, flags a difference in style between Western and Japanese thought: whereas much Western thought aims for clarity, detail, and distinctiveness, Japanese thought appreciates the unspoken, allusion, hinting, and imagination. In part, this is an issue of politeness, or an orientation to not call things by name. One way of articulating this difference is ‘to think for the reader’ and ‘to permit the reader to think for himself’ (Schinzinger, in Nishida, 2003 [1958]: 3). A reason for this is the Japanese starting position of the whole and totality, not discrete parts. The issue of “wholes” and contexts, over parts and particularities, has already been a feature of this paper, but Schinzinger also remarks that, ‘In general it may be stated that Japanese thinking has the form of totality (Ganzheit): starting from the indistinct total aspect of a problem, Japanese thought proceeds to a more distinct total grasp by which the relationship of all parts becomes intuitively clear’ (Schinzinger, in Nishida, 2003 [1958]: 6).

To illustrate priority of the whole: ‘Ordinarily, we think of the material world, the biological world, and the historical world as being separate. But in my view, the historical world is the most concrete, and the material and biological worlds are abstractions. Thus, if we grasp the historical world, we grasp reality itself’ (Nishida, cited in Feenberg, 1995: 158). Nishida is not rejecting empiricism or reason, but refusing these as the basis or beginning of understanding. Rather, reason should be interpreted historically and as only one part of our lives.

Temptation to set up occidental/oriental stereotypes should be avoided. Emphasis on the primacy of history is well-rehearsed in Western thought, with many Japanese philosophers being aware of European Counter-Enlightenment thought. Indeed, the eighteenth-century philosopher Giambattista Vico was a favourite of Watsuji ([1937] 1996), having published a biographical essay about him. Vico was also a poster-thinker of resistance against the formalism of modernity by Japanese philosophers, such as Hani Gorō, Miki Kiyoshi, Kobayashi Isami, Aoki Iwao, Shimizu Jun’ichi, and Shimizu Ikutarō (Campagnola, 2010).

On ethics, for Nishida (2003 [1958]), goodness and moral virtue are superseded by acknowledgement of a larger cosmological self-unfolding whole (or nothingness). The point about self-unfolding is an important one: virtue is not static, but dynamic. Cosmological pragmatism thus means that ethics are to change and re-description through a pragmatism instigated by “nothingness” (recognition of teeming multiplicity, rather than emptiness or negation of life). This multiplicity comes from a ‘unity of opposites’ as the many and one challenge each other, contradict and grow, arguably in a positive feedback loop—a condition of change and growth, and new forms of equilibrium and poiesis. The ethical difference is the ongoing deference to the totality (of infinite nothingness) that this takes place within. Yet, while respectful, Nishida’s nothingness is also anti-conservative, finding resonance in the process philosophies associated with James, Bergson, Whitehead, Stengers, and even Deleuze that sees form from formlessness. This is a positive account of cosmic self-unfolding, one that will be argued below to be important for technology ethics due its anti-conservativism.

6.2 Cosmological Pragmatism

Nishida’s work on modernity and Buddhism perhaps helps explain the energy and divergent behaviours of Japanese culture (and why the traditional lives on alongside popular techno-culture). For Nishida, the nature of historical action is that the present is an expression. Certainly, the past is with us and acts as strong presence, but for Nishida there is a deep and somewhat cosmological pragmatism at play. Given the absence of a transcendent elsewhere, a person makes and shapes this world (beginning with personal consciousness). In other words, one recognises the cosmological movement, connectedness with the past and others, but simultaneously takes a conscious stand in the unfolding. This dualism is a core characteristic: self-hood is understood in relation to what it is created by (and informs). At the level of society and the state, this unity of opposites again provides a necessary contradiction (as first raised with Watsuji) that allows for societal positive feedback and novel self-formation.

Applied, this helps explain Japan’s simultaneous embracing of the new, alongside a deep appreciation of the absolute whole. Thus, for society to advance, it must be challenged by individuals, whose expressions are society challenging and growing itself. This is social, cultural, technological, and normative poiesis in action, but again taking place against reverence for the whole. A surface reading might see poetics of capitalism and creative destruction, but there is more to it. This is found in the negation of selfhood and realisation that individual expression (and the dynamics of desire) is self-formation of the world.

Nishida’s (2003 [1958]) Western-friendly articulations of Buddhism lend a frame for understanding Japan’s capacity for self-reinvention, renewal, and engendering of technically infused societal formations. Japanese ethics also have a very practical dimension because of its Buddhist influence and its cosmological pragmatism. Certainly, the past is carried into the future, but both are part of a larger cosmological self-unfolding whole (or nothingness). To again quote Nishida, ‘In moving from form to form the world constantly renews itself’ (2003 [1958]: 60). Self-formation of the unfolding whole is at the same time self-expression, which provides a delicious paradox resolved for Nishida at the level of consciousness. As one is simultaneously environment and subject, the colliding point is consciousness (which is nothingness being aware of itself).

Ethics, too, are subject to re-description. Again, echoing pragmatist ethics, Nishida says, ‘Something like moral reality can be comparted with an eternally unfinished piece of art’ (2003 [1958]: 118). There is a clear bridge to Western understanding by recognising the deep connection with pragmatism and its context-based passion, care, and willingness to defend, even when ethics are ethnocentric and local in nature (Rorty, 1989; Dewey, 1995 [1908]; James, 2000 [1907]). Likewise, for Nishida, also unashamed of historical relativism, there is ‘neither “good” nor “evil”’, but a constant enveloping of Universals (Nishida, 2003 [1958]: 130).

The need to begin with the whole rather than its parts is a fundamental orienting point for Japanese beliefs and, as argued below, the second of the four ethical Spices (wholeness). As Nishida (2003 [1958]) notes, the issue of wholeness (Ganzheit) is not reliant on any one Japanese belief, but is a starting position for much Japanese thought. In Shinto, for example, Kami is both hidden yet complementary to material life, and exists as a singular divinity that manifests in multiple forms and items of daily use. The Zen Buddhist dimension also alludes to wholes rather than descriptive specifics, with this interest in wholes lending a highly non-conservative character that recognises the contingency of moments, circumstance, and contexts. This whole has characteristics of immanence, providing for a cosmological pragmatism. This is because as there is no transcendent elsewhere, people make and shape this world. Also, for society to advance, it must be challenged by individuals, whose expressions are the “whole” challenging and growing itself. Deeply contextual, this pragmatic view of ethics means that both the state and its legal structures are not the arbiters of ethics, but values co-created by citizens and non-citizen dialectics on any given social arrangement (ningen).

Neither cosmological pragmatism, nor the creative dynamics of Watsuji’s ningen (self/community dialectic), accord easily with trans-contingent hard-won human rights. Usefully, Morita (2012) does not see international human rights as incompatible with “Asian values,” but argues that universal human rights must be justified in a region’s own terms and perspectives. This sits well with wider suggestions on ethical pluralism (Ess, 2020) and scope for the same ethics to be meaningfully adhered to for different cultural reasons (Hongladarom, 2016). There is a danger that this is an ethical bodge, with ÓhÉigeartaigh et al. (2020) and Wong (2009) raising concern that shared norms with different justifications is an inadequate outcome. Yet, as ÓhÉigeartaigh et al. (2020) also argue, this paper believes that an overlapping consensus is preferable to either (1) no consensus, or (2) a fight to impose one’s own belief system. Pragmatically oriented, it also contends that lack of willingness to update ethical positions and ideological entrenchment must be resisted, in favour of ongoing alertness to what may be learned from the other, perhaps especially so when new technological applications raise novel ethical questions. With regional justification in place, Morita observes that ‘an overlapping consensus in the norms of human rights may emerge from these self-searching exercises and mutual dialogue’ (Morita, 2012: 360). The ethical recommendation that flows from this is that while Zen Buddhist-inspired ethics butts against deontic principles in human rights, this may be seen as an opportunity to advance human rights in an age where AI decision-making and emotional AI have scope to profoundly impact human life. Cosmological pragmatism also lends scope for soft ethics (Floridi, 2018), in that while the hard ethics of law and normative adherence remains paramount (ibid), there is also scope for dynamic contexts co-created by citizens and non-citizen dialectics (ningen). The key ethical recommendation here is that dialectical spaces in cities and towns should be made for local agreements. While this will not breach more formal hard ethics (those enacted in law for example), it provides scope for dynamic local arrangements. This has resonance in the West with Green’s (2020) argument for a more direct democracy when it comes to companies seeking to roll out new data-oriented applications in towns and cities.

7 AI Ethics and Emotion: the Values of Japanese Spice

We can now consider global ethical lessons from classical and modern thought in Japan, in relation to emerging technological contexts. Indeed, for a country with beliefs that diverge so significantly from Europe’s, it seems strange that there is not more ‘Japanese spice.’ This is not to suggest that core beliefs should not be liberally minded, especially given (rightly or wrongly) the embrace of liberal ideas since the Meiji Restoration. Yet, more spice is required, especially given the close attention paid by Japanese philosophers to the facilitative and connectionist role that technologies play in the emergence and identity of societies. Argued below, this gives rise to an appreciation of the four spices of community, wholeness, sincerity, and heart. As remarked in “Introduction”, without a doubt, more spices may be found, yet the four identified here have wide applicability.

7.1 Spice 1: The Value of Including a Community-Based Perspective

While Japan’s AI policies, and its implementation of international adequacy agreements means that it has a formal ethical agreement with other regions, it is worth noting that “ethics” have a regional flavour. Ethics (Rinri) for Japan is indissociable from community-based perspectives, involving ways to order and maintain socially harmonious relationships. In relation to Society 5.0, a key Japanese policy development for embedding AI systems in everyday life, Berberich et al. (2020) points to a ‘convivial’ society, in which humans and intelligent non-human information systems would live in harmony. Wong (2012) explains that for Confucians the principle of harmony stems from the ideal relationship between human beings and Heaven, which is harmonious rather than confrontation or divided. Critically, human beings and Heaven ‘are of the same nature ontologically’ (ibid: 72). To defuse potential for mystical readings of ‘Heaven’, Wong (2012) quotes Tu Weiming who, reminiscent of Watsuji, identifies Heaven as the ‘interconnectedness of all the modalities of existence defining the human condition’ and ‘an ever-expanding network of relationships encompassing the family, community, nation, world, and beyond’ (Tu, 1993: 141).

Drawing on Confucian principles of harmony with nature, Society 5.0 sees scope for harmony with the information environment. This is facilitated by a view of nature (shinzen) that is more expansive than Western ideas that focus on the natural environment. This leads Berberich et al. (2020) to propose that ‘the addition of the concept of harmony to the discussion on ethical AI would be highly beneficial due to its centrality in East Asian cultures and its applicability to the challenge of designing AI for social good’ (2020: 1). In Japan, the term for harmony is Wa, which Berberich et al. (2020) argue to be the country’s most important value. Derived from the Confucian ideal of harmony, yet interacting with Shinto and other beliefs regarding politeness, Wa developed its own character. Critically, Wa is not conformity, nor does it mean conservativeness. One may for example be respectful, yet clearly state one’s position, and Wa may also have a creative character that allows for newness and growth. For example, harmony or Wa may grow to encompass connectivity with non-human actors, involving diverse forms of AI systems. Be it human-system or human–human, a harmony-based approach is one suited to the modern digital life. As outlined, for Watsuji (1996 [1937]), this is ‘in-betweenness’ of people established through communitarian interconnectedness, one that focuses on terms of connectivity and group dynamics, while not omitting individuals. Applied, this individual and collective dyad matters, especially for group harms caused by emergent forms of civic profiling involving emotion and physiognomic-inspired profiling of people in urban spaces (McStay, 2018). Whereas European Union AI and data protection typically entails personal data (that rests philosophically on rights to self-determination), a community-based perspective (or spice) is here argued to be of high ethical value. Japanese in-betweenness, or that which orients and exists between people, can be readily used to further universal arguments that values such as privacy are not only individual, but collective rights. Although human rights law recognises collectives (and dangers of seeing communities as corporate entities) (Dinstein, 1976), the Japanese “in-betweenist” spice makes a unique connectionist and “whole” based contribution. Expanded beyond use of emotional AI in urban contexts, Spice 1 also advances interests in algorithmic discrimination, undesirable social influence through networks, data justice concerns, and related concerns predicated on mining the nature of social connections, big data, inferences from arguably non-personal data, and influence techniques derived from wholes and background life contexts.

7.2 Spice 2: The Value of Wholes and Aversion to Objectification

The critique of scientific reductionism is one associated in the West with mining, making present, excavation of subjectivity, and representing and mediating it via unnatural (distorted) means. For the West, this narrative finds the best expression in Heidegger’s (2013 [1941–2]; 1993 [1954]) critique of technology and technological rationality, as the ways in which technical rationality equates being with presence and objectification. Given Japan’s belief systems and their modern articulations (that included engagement with Heidegger), the objectification critique, or Spice 2, acquires extra importance given the upfront need to understand the whole from which a part is depicted. Connected, while one could argue that all scientific breakthroughs are due in some way to reduction of the world’s complexity, concern about machine learning techniques (especially bias in/bias out) is about what is lost from the social in the process of reduction. Similarly, critique of emotional AI frequently focuses on what is missed when geometries of facial expressions are extracted from the holism of lived contexts (Azari et al., 2020). Japanese need to acknowledge or allude to wholes (contexts) in art has bearing for Spice 2. In the discussion of art, for example, Nishida (2003 [1958]: 145–6) observes that Japanese art differs from Western modes of representation because it includes its background as an integral element, to acknowledge that from which form is drawn. This points to a need to grasp life itself, rather than particularities; an aversion to making all things present for open inspection; an appreciation for allusion, hinting and acknowledgement; and politeness, or that orientation that does not like to call things by name. Here, Spice 2 takes the form of an ethical recommendation that global aversion to dehumanisation through objectification and decontextualization should recognise Japanese respect for the whole from which particularities are derived. Practically, particularities, in the form of machine decisions and judgements, might refer and “clearly allude” to the limits of contextual understanding by which judgements are made, so the background to the decision is clear. To an extent, this is a restatement of universal interest in decisional transparency for governance of AI and big data processing. Yet, this paper takes seriously Morita’s (2012) argument that universal human rights may be justified in a region’s own terms and perspectives. A key reason is that such an approach allows the region and its regulators to take ownership of prescriptions, and to put them into practice in ways that have stronger normative resonance for citizens and those required to follow the rules.

7.3 Spice 3: The Value of Sincere Conduct

Stereotypes of Western individualism and Eastern collectivism are sometimes used to signify that Westerners care more about privacy. However, Confucius’ statement that, ‘In practicing ritual one does not go beyond the proper measure, nor take liberties with others, nor presume an intimacy with others’ is keenly significant for AI ethics and questions of emotion profiling (Confucius, cited in Gardner, 2014: 25). For Spice 3, the requirement of sincere conduct, this is an important set of practical sentiments with which to consider AI that uses individual and collective data: ‘proper measure’ indicates respect for decorum; ‘take liberties’ means not to take advantage of, nor to abuse a social situation; and not to ‘presume an intimacy’ has special relevance for emotional AI. From the point of those who seek to engage with others, what is clear is that Confucianism demands good sincere conduct, potentially linking with ethical questions around transparency of intention, absence of manipulative uses, and privacy.

Indeed, privacy and conduct may also be approached from a Buddhist orientation, given the property-based dimension to privacy evident in Nishida. Pointing out that ‘the individual has its subjective in the objective world’ (2003 [1958]: 202) and that, ‘Property must find its expression in the [objective] world, as belonging to a certain individual; it must be recognised by the [objective] sovereignty’ (ibid [my emphasis]). In contrast to a natural rights account of privacy and selfhood, the implication of Nishida’s articulation of Buddhist principles in the modern context is that property is the foundation of privacy. Dedicated privacy scholars will be aware that privacy-as-property is an unpopular view (certainly in Europe) due to the marketisation of subjectivity, but perhaps the best way of reading Nishida is not in terms of market logics (privacy ‘have’s and ‘have nots’) but his attempt to find a practical and non-deontological method to formalize an objective right of subjective life. This has precedent too in what Murata (2019) accounts for as ‘vocational ethics,’ a traditional, practical, and civically minded approach to ethics and commerce, rather than dehumanised modes of neoliberal exchange.

7.4 Spice 4: Heart and the Value of Sensitivity to “Synthetic” Life

Of Japan and social robots, Robertson (2018) describes the extension of Shinto-based religious rites to the disposal of robots, such as Sony’s AIBO. Katsuno (2011) helps explain this, stating that for English speakers, ‘heart’ is a human phenomenon and that through this we feel emotionally ‘touched’ by others. Katsuno argues however that the attribution of ‘heart’ (or kokoro) to humanoid robots is pervasive in contemporary Japan. This has origins in the 1890s, as the Buddhist-inspired philosopher Minakata accounted for kokoro as ‘heart-mind,’ also describing the ‘inter-work’ of substance (mono) with heart-mind. This relationship generated its own form of ‘causality,’ which is an attempt to bridge subject-object relations by means of what events are caused by the intermingling of kokoro and mono, and even feedback loops between heart and substance thereafter (Sato, 2019). This affective connection finds ready expression in human–computer interaction, and personal and social experience of synthetic personalities built with affect-sensitive sensors and actuators, albeit of a different character to that inspired by cybernetics, behaviourism, and cognitivist outlooks. Sony’s approach to AI ethics is telling, aiming to ‘contribute to the development of a peaceful and sustainable society while delivering kando—a sense of excitement, wonder, or emotion—to the world’ (Sony, 2019). The ambition to move people affectively and emotionally is thus key to Sony’s mission strategy. Sony also states that it will utilize AI ‘in a manner harmonized with society’ (which is Confucian); that ‘Sony aims to support the exploration of the potential for each individual to empower their lives’ (liberal and originally Western); and to contribute to enrichment of our culture and push our civilization forward’ (influences of Meiji and wakon yōsai) by providing novel and creative types of kando (Shinto, and its loosening of subject/object binaries that allow for emotionally charged entities).

On animism itself, as Kitano (2007) notes, Japanese animism is born from qualities of immanence and the existence of spiritual life that is not simply individual subjectivity, but relationships with “the whole”. Key is the decentring of sovereign subjectivity and the self-positing human at the centre of existence. Again, this is an appeal to larger non-human wholes, in favour of a more ecological view that accepts that various modes of existence are fused together. Pointing to what he sees as a greater sensitivity of the Japanese towards things, Nishida (2003 [1958]: 52) articulates ‘Japanese culture’ as a culture of emotion that derives from a phenomenological openness guided by an intention to the full nature of a thing, rather than a learned reductionist blinkeredness. Related, Kaplan (2004) argues that ‘Japanese people do not oppose the natural and the artificial but on the contrary very often use the artificial to recreate nature’ (2004: 5). Interest in honouring nature through mimicry stands in contrast to views based on the corruptive influences of technology, arguably rooted in Rousseau (2008 [1762]), and the conservative concern with preservation of human authenticity and the ruining of a human-centred nature.

Yet, Robertson (2018) notes that the principle of ‘nature’ (shinzen) is very pliable, meaning more than environment or ecology (also see Ito, 2016). Rather (like Kami), nature exists in multiple forms, in organic and non-organic things. This paper will not argue for spirits in things, recognising the tension between animistic beliefs and capitalist interests in the design of synthetic personalities. It also sees social dangers of emotional AI and synthetic personalities, perhaps foremost in relation to children and elderly people experiencing the effects of brain degeneration. Yet, for Spice 4, there is ethical and governance value in Japanese sensitivity to the intelligences we build and live alongside, specifically given historic understanding of in-betweenness of things (especially designed things) and people (Nakada, 2019), which has roots in Watsuji- and Heidegger-influenced ideas about interaction as the basis of meaning. This applies well to the psychological experiences of systems where subjects and objects may modify (however slightly) each other. As explored then, Japanese philosophies encourage experiential openness, sensitivity to contexts, recognition of human values in technology, aesthetic and affective awareness of things, and relationships with synthetic personalities. Spice 4 is thus a policy need for experiential sensitivity to objects, systems, synthetic personalities, emergent relationships, and the complex interactions that will surely emerge as emotion and affect-based systems grow more sophisticated in their capacities to simulate understanding of intimate dimensions of human life.

8 Conclusion

With Japan and emotional AI systems in mind, this paper has considered technology ethics in relation to non-Western ethical thought and practice. Its starting point was the Meiji Restoration that initiated Japan’s first modernity. By assessing both liberal-inspired philosophers, and those exploring the intersections between Japanese and Western understanding of experience, the paper progressed to illustrate interests of value to Japanese AI ethics policy, so as not to rely so heavily on ‘dignitarian philosophy’ (Miyashita, 2021). It then made recommendations on factors that might be recognised (1) internally within Japan’s national AI policies, and (2) externally (internationally) in standards and rights-based debates on how to govern AI technologies. This is to rebalance ethical debate from what arguably are largely US and European normatively dominated debates, but also because the factors are innately valuable for discussion of governing AI technologies that judge and interact with emotion and other intimate dimensions of human life. Presented as the four Spices (the value of a community-based view, aversion to objectification without context, sincere conduct, and sensitivity to emergent relations with technologies), these are argued to have application to global conversation on moral principles governing emerging AI technologies.

Confucian-led principles of harmony and inter-dependency have much to offer because they admit that nature and environments may be technological as well as organic. From the point of view of ethics, a harmony-based approach de-emphasises individuals (seeing them as one part of a necessary contradiction). Practically, given that there are increasingly many questionable uses of data about people that do not strictly make use of personal data, such as through synthetic data, or processing that stops short of being able to single-out a person yet clearly affects groups of people, a harmony-based in-betweenist approach that recognises civic and societal impact is normatively welcome to help advance policy on collective data rights.

The cosmological pragmatism of Zen Buddhist–inspired technology ethics sits uncomfortably with deontic ethical principles. Yet, it provides a useful ethical impetus for locally and contextually applied governance that recognises change and impermanence. From a governance point of view, in relation to smart cities (and Japan’s Society 5.0), this is not unlike Green’s (2020) argument for a more direct democracy when it comes to companies seeking to roll out new data-oriented applications in towns and cities. Family, regional, and corporate communities are also stressed by Nishigaki (2006), who observes that both in traditional and modernized Japanese societies, the communities to which individuals belong have complex features in terms of internal behavioural codes. Assuming international and national law are in place, dynamic and local ethical contexts may be co-created by citizens and non-citizen dialectics (ningen), something that is increasingly necessary as ubiquitous sensing becomes more prevalent in local life.

On privacy harms, these are framed in Japanese policy in terms of dignity, but as Miyashita (2021) highlights, this term does not resonate as well in Japan as it does in Europe. Respect for Miyashita is a better perspective, a critique arguably Confucian in nature, especially regarding the need to take proper measures and not to presume intimacy. Ultimately this is about good conduct, providing clear guidance (perhaps more practical and intuitively straightforward than dignity) on the need for decorum regarding the collection and processing of personal data. Respect can also be expanded to include respect for lived context and the whole from which particularities have been taken, to avoid dehumanisation and objectification through decontextualization. This gives moral form, for example, to potential harms through automated individual decision-making, where important decisions about a person (such as workplace performance through emotional AI) are made based on potentially decontextualised data. Such a moral remedy would mean not only the ability to challenge the accuracy of data, but also the right to acknowledge the wider situation that the decontextualised data was taken from.

Finally, the cultural sensitivity of the Japanese to relationships with non-human agents, the lack of an absolute divide between artifice and nature, and that the artificial can be seen as honouring the organic should be noted. The various traditions discussed here, and how modern Japanese philosophies of modernity hybridised these, point to potential for ethical and policy sensitivity to emergent human-system interactions. These will continue to involve data, but increasingly includes relationships with synthetic agents in phones, playthings, homes, and elsewhere. Yet, from the point of view of ethical factors that impact on the design of AI services that make use of intimate dimensions of human life, much can be learned globally from Japan’s affective connections, complex relational factors, and what will be much needed experiential sensitivity to relationships with non-humans.

Notes

Japanese names are historically written with the family name preceding their given name. Thus, the author Watsuji Tetsurō will be cited by the family name Watsuji. Where an author publishes family name last, they will be cited and recorded in the reference list accordingly.

References

Agency for Culture Affairs (2019) 宗教年鑑 令和元年版 [Religious Yearbook 2019], Government of Japan. Retrieved August 4, 2021, from https://www.bunka.go.jp/tokei_hakusho_shuppan/hakusho_nenjihokokusho/shukyo_nenkan/pdf/r01nenkan.pdf#page=49

Altenberger, F. & Lenz, C. (2018). A non-technical survey on deep convolutional neural network architectures, arXiv. Retrieved August 4, 2021, from https://arxiv.org/pdf/1803.02129.pdf

Azari, B., Westlin, C., Satpute, A. B., et al. (2020). Comparing supervised and unsupervised approaches to emotion categorization in the human brain, body, and subjective experience. Scientific Reports, 10(20284), 1–17.

Berberich, N., Nishida, T., & Suzuki, S. (2020). Harmonizing artificial intelligence for social good. Philosophy & Technology, 33, 613–638. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13347-020-00421-8

Cabinet Office. (2019). Social principles of human-centric AI (draft). Retrieved August 4, 2021, from https://www8.cao.go.jp/cstp/stmain/aisocialprinciples.pdf

Campagnola, F. (2010). At the outskirts of modernity: A brief history of Giambattista Vico’s reception in Japan. Intellectual News, 16, 179–190. https://doi.org/10.1080/17496977.2010.11417801

Carter, E.E. (2013) The Kyoto School: An introduction. SUNY Press.

Culiberg, L. (2015). Kangaku, kogaku, kokugaku, rangaku: reinterpretation of Confucianism in the nation building process in Japan. In J.S. Rošker, Jana S & N. Visočnik (Eds.), Contemporary East Asia and the Confucian Revival. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 3–22.

Daly, A. (2021). Neo-liberal business-as-usual or post-surveillance capitalism with european characteristics? The EU’s general data protection regulation in a multi-polar internet. In R. Hoyng & G. Pak Lei Chong (Eds.), Communication innovation and infrastructure: A critique of the new in a multipolar world. MSU. Retrieved August 4, 2021, from https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3655773

Dewey, J. (1995 [1908]). Does reality possess practical character. In R.B. Goodman (Ed.), Pragmatism: A contemporary reader. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003061502-6

Dinstein, Y. (1976). Collective human rights of peoples and minorities. The International and Comparative Law Quarterly, 25(1), 102–120.

Ess, C. M. (2020). Interpretative pros hen pluralism: From computer-mediated colonization to a pluralistic intercultural digital ethics. Philosophy of Technology, 33, 551–569. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13347-020-00412-9

European Commission. (2021). Proposal for a regulation laying down harmonised rules on artificial intelligence (Artificial Intelligence Act). Brussels: European Union. Retrieved August 4, 2021, from https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/proposal-regulation-laying-down-harmonised-rules-artificial-intelligence

Expert Group on Architecture for AI Principles to be Practiced. (2021). AI governance in Japan Ver. 1.0. Retrieved August 4, 2021, from https://www.meti.go.jp/press/2020/01/20210115003/20210115003-3.pdf

Feenberg, A. (1995). The problem of modernity in the philosophy of Nishida. In. J. Heisig & J. Maraldo (Eds.), Rude awakenings: Zen, the Kyoto School and the question of nationalism, University of Hawaii. Pp. 151–173. Accessed August 4, 2021 https://www.sfu.ca/~andrewf/books/Problem_of_Modernity_Philosophy_Nishida.pdf

Fukuzawa, Y. (2007 [1893]). The autobiography of Yukichi Fukuzawa, trans. E. Kiyooka. CUP. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0035869x00125523

Fukuzawa, Y. (2012 [1872–6]). An encouragement of learning, trans. D.A. Dilworth. CUP. https://doi.org/10.7312/columbia/9780231167147.001.0001

Gardener, D.K. (2014). Confucianism: A very short introduction. OUP. https://doi.org/10.1093/actrade/9780195398915.001.0001

Goto-Jones, C. (2009). Modern Japan: A very short introduction. OUP. https://doi.org/10.1093/actrade/9780199235698.003.0001

Government of Japan. (2020) Super City Initiative, Accessed August 4, 2021 https://www.kantei.go.jp/jp/singi/tiiki/kokusentoc/supercity/supercityforum2019/AboutSuperCityInitiative.pdf

Green, B. (2020). The smart enough City. MIT. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/11555.001.0001

Hardacre, H. (2017). Shinto: A history. OUP. https://doi.org/10.1086/698991

Havens, T.R.H. (1970). Nishi Amane and modern Japanese thought. Princeton. https://doi.org/10.1086/ahr/75.7.2110

Heidegger, M. (1993 [1954]). The question concerning technology. In D.F. Krell (Ed.), Basic Writings. Harper Collins.

Heidegger, M. (2011 [1962]). Being and time. Harper & Row.

Heidegger, M. (2013 [1941–2]). The event. IUP.

Hongladarom, S. (2016). Intercultural information ethics: A pragmatic consideration. In M. Kelly & J. Bielby (eds), Information cultures in the digital age. Springer VS. Pp. 191–206. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-14681-8_11

Ito, J. (2016). Extended intelligence. Retrieved August 4, 2021, from https://pubpub.ito.com/pub/extended-intelligence/release/1

James, W. (2000 [1907]). Pragmatism and other writings. Penguin.

Kaplan, F. (2004). Who is afraid of the humanoid? Investigating cultural differences in the acceptation of robots. International Journal of Humanoid Robotics, 1(3), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-14681-8_11

Katsuno, H. (2011). The robot’s heart: Tinkering with humanity and intimacy in robot-building. Japanese Studies, 31(1), 93–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/10371397.2011.560259

Kitano, N. (2007) Animism, rinri, modernization; The base of Japanese robotics. Retrieved August 4, 2021, from http://www.roboethics.org/icra2007/contributions/KITANO%20Animism%20Rinri%20Modernization%20the%20Base%20of%20Japanese%20Robo.pdf

Lennerfors, T.T. (2019) Watsuji’s ethics of technology in the container age. In. T.T. Lennerfors & K. Murata (eds), Tetsugaku companion to Japanese ethics and technology. Springer. Pp. 59–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-59027-1_4

Lennerfors, T.T. & Murata, K. (2019) Introduction: Japanese philosophy and ethics of technology. In. T.T. Lennerfors & K. Murata (eds), Tetsugaku companion to Japanese ethics and technology. Springer. Pp. 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-59027-1_1

Li, C. (2006). The Confucian ideal of harmony. Philosophy East and West, 56(4), 583–603. https://doi.org/10.1353/pew.2006.0055

Lipton, Z.C., Berkowitz, J., Elkan, C. (2015). A critical review of recurrent neural networks for sequence learning, arXiv. Retrieved August 4, 2021, from https://arxiv.org/abs/1506.00019

McStay, A. (2018). Emotional AI: The Rise of Empathic Media. Sage.

Mitchell, D.W. and Jacoby, S.H. (2014). Buddhism: Introducing the Buddhist experience. OUP.

Miyashita, H. (2021). Human-centric data protection laws and policies: A lesson from Japan, A lesson from Japan. Computer law & security review, 40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clsr.2020.105487

Morita, A. (2012). A neo-communitarian approach on human rights as a cosmopolitan imperative in East Asia. Filosofi a Unisinos, 13(3), 358–366. https://doi.org/10.4013/fsu.2012.133.01

Murata, K. (2019) Japanese traditional vocational ethics: Relevance and meaning for the ICT- dependent society. In. T.T. Lennerfors & K. Murata (eds), Tetsugaku companion to Japanese ethics and technology. Springer. Pp. 139–160. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-59027-1_7

Nishida, K. (2003 [1958]). Intelligibility and the philosophy of nothingness: Three philosophical essays. Trans and Intro, R. Schinzinger. Facsimile.

Nishigaki, T. (2006). The ethics in Japanese information society: Consideration on Francisco Varela’s The Embodied Mind from the perspective of fundamental informatics. Ethics and Information Technology, 8, 237–242. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10676-006-9115-1

ÓhÉigeartaigh, S. S., Whittlestone, J., Liu, Y., Zeng, Y., & Liu, Z. (2020). Overcoming barriers to cross-cultural cooperation in AI ethics and governance. Philosophy of Technology, 33, 571–593. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13347-020-00402-x

Ren, S., He, K., Girshick, R. & Sun, J, (2015). Faster R-CNN: Towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks, arXiv. Retrieved August 4, 2021, from https://arxiv.org/abs/1506.01497

Robertson, J. (2018). Robo sapiens Japanicus: Robots, gender, family, and the Japanese nation. Oakland: University of California Press. https://doi.org/10.1525/california/9780520283190.001.0001

Rorty, R. (1989). Contingency, irony and solidarity. CUP. https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9780511804397

Rousseau, J.J. (2008 [1762]). The social contract. Cosimo.

Sato, M. (2019). Minakata Kumagusu – Ethical implications of the great naturalist’s thought for addressing problems embedded in modern science. In. T.T. Lennerfors & K. Murata (eds), Tetsugaku companion to Japanese Ethics and technology. Springer. Pp. 75–105. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-59027-1_5

Seymour, W. and Van Kleek, M. (2020). Does Siri have a soul? Exploring voice assistants through Shinto design fictions, CHI 2020. Pp. 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1145/3334480.3381809

Sony. (2019). AI engagement within Sony Group. Retrieved August 4, 2021, from https://www.sony.net/SonyInfo/csr_report/humanrights/AI_Engagement_within_Sony_Group.pdf

Suzuki, D.T. (1959). Zen and Japanese culture. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Toshio, K., Dobbins, J. C., & Gay, S. (1981). Shinto in the history of Japanese religion. The Journal of Japanese Studies., 7(1), 1–21.

Tu, W. (1993). Confucianism. In A. Sharma (Ed.), Our religions. Harper Collins. Pp. 139–227.

Tucker, M. E. (1998). Religious dimensions of Confucianism: Cosmology and cultivation. Philosophy East and West, 48(1), 5–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-59027-1_5

Vermeersch, S. (2020). Syncretism, harmonization, and mutual appropriation between Buddhism and Confucianism in pre-Joseon Korea. Religions, 11(5), 231. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11050231

Vico, G. (2001 [1725]). The new science of Giambattista Vico, trans. D. Marsh. Penguin Books.

Watsuji, T. ([1937] 1996). Watsuji Tetsurō’s Rinrigaku: Ethics in Japan, trans. Y. Seisaku and R.E. Carter. SUNY.

Watsuji, T. (1961). A climate: A philosophical study, trans. G. Bownas. Printing Bureau, Japanese Government.

Wong, P.-H. (2009). What should we share? Understanding the aim of intercultural information ethics. ACM SIGCAS Computers and Society, 39(3), 50–58. https://doi.org/10.1145/1713066.1713070

Wong, P.-H. (2012). Dao, harmony and personhood: Towards a Confucian ethics of technology. Philosophy and Technology, 25(1), 67–86. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13347-011-0021-z

Funding

This work is supported by Economic and Social Research Council (ES/T00696X/1).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

McStay, A. Emotional AI, Ethics, and Japanese Spice: Contributing Community, Wholeness, Sincerity, and Heart. Philos. Technol. 34, 1781–1802 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13347-021-00487-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13347-021-00487-y