Abstract

In recent years, scholars have sought to investigate the impact that ethical leaders can have within organisations. Yet, only a few theoretical perspectives have been adopted to explain how ethical leaders influence subordinate outcomes. This study therefore draws on social rules theory (SRT) to extend our understanding of the mechanisms linking ethical leadership to employee attitudes. We argue that ethical leaders reduce disengagement, which in turn promotes higher levels of job satisfaction and organisational commitment, as well as lower turnover intentions. Co-worker social undermining is examined as a moderator of the relationship between ethical leadership and disengagement, as we suggest that it is difficult for ethical leaders to be effective when co-worker undermining prevails. To test the proposed model, questionnaires were administered to 460 nurses in Romanian hospital settings over three time points separated by two-week intervals and the hypotheses were tested using generalised multilevel structural equation modeling (GSEM) with STATA. The findings revealed that ethical leadership has a beneficial effect on employee attitudes by reducing disengagement. However, the relationship between ethical leadership and disengagement was moderated by co-worker social undermining, such that when undermining was higher, the significance of the mediated relationships disappeared. These results suggest that while ethical leaders can promote positive employee attitudes, their effectiveness is reduced in situations where co-worker undermining exists.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, geo-political turbulence and moral failures at multinational organisations have increased interest in ethical leadership. Ethical leadership involves demonstrating normatively appropriate behaviour towards followers through the use of two-way communication, reinforcement, and decision-making (Brown et al. 2005). Research and meta-analyses have shown that working for an ethical leader is associated with lower turnover intentions and higher levels of job satisfaction and organisational commitment (Ng and Feldman 2015; Demirtas and Akdogan 2015; Bedi et al. 2016; Hoch et al. 2018; Wang and Xu 2019). However, Wang and Xu (2019, p. 920) state that our understanding of the relationship between ethical leadership and employee attitudes is “still far from complete”. This is mainly because prior research has relied on social exchange and social learning theories to explain how ethical leadership is related to employee attitudes, which only provide a partial picture of how ethical leadership exerts an impact (Wang and Xu 2019). This study moves beyond social exchange and social learning theories and draws on social rules theory (SRT; Henderson and Argyle 1986) to advance our knowledge of the mechanisms and boundary conditions of the relationship between ethical leadership and employee attitudes. SRT proposes that the violation of social rules is negatively associated with employee wellbeing and attitudes, while rule compliance is positively related to wellbeing and attitudes (Henderson and Argyle 1986).

We firstly examine the mediating role of disengagement in the relationship between ethical leadership and job satisfaction, organisational commitment, and turnover intentions. Disengagement is one of the main dimensions of burnout (Bakker et al. 2004). It involves distancing oneself “from one’s work in general, work object and work content” (Demerouti et al. 2010, p. 210). Limited attention has been directed towards disengagement and its antecedents (Pech and Slade 2006; Hejjas et al. 2019). Instead, researchers have mainly studied work engagement. However, recent research has shown that engagement and disengagement are “not opposites” and that different factors could drive or inhibit each construct (Hejjas et al. 2019, p. 329). Research has also shown that, contrary to not being engaged, which is a passive reaction to work, disengagement has an active nature because it could drive employees into active behaviours like withdrawal (Parkinson and McBain 2013). Disengaged employees are less productive and can harm organisations by engaging in unethical behaviour, presenteeism and by sharing negative attitudes with others (Carter and Baghurst 2014). Since many managers are unsure about the causes of disengagement and interventions that could minimise it (Pech and Slade 2006), more research is needed on how it could be reduced (Pech and Slade 2006; Hejjas et al. 2019). Using SRT, we argue that ethical leadership is associated with improved employee attitudes because ethical leaders reduce disengagement by upholding social rules that guide the relationships between supervisors and subordinates. These include giving clear guidance, organising work effectively, acting with fairness, and communicating with followers.

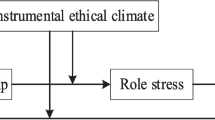

Secondly, we examine the role of co-worker social undermining as a moderator of the relationship between ethical leadership, disengagement and consequently employee attitudes of job satisfaction, commitment, and quit intentions (see Fig. 1 for the conceptual model). Co-worker social undermining is a form of workplace mistreatment that reduces a person’s ability to create and maintain good relationships, success, and a positive reputation at work (Duffy et al. 2002). Supervisors and co-workers are “the most important functional and social constituencies in an organisation” (Duffy et al. 2002, p. 331). Since our focus is on determining the boundary conditions of ethical leadership and how its effectiveness could be impaired when social rules are broken by a source other than the supervisor, co-worker undermining was chosen in this study. Drawing on SRT, we argue that co-worker social undermining is a form of rule-breaking behaviour that limits the effectiveness of ethical leadership. We suggest that under conditions of higher social undermining, the negative relationship between ethical leadership and disengagement becomes weaker, thus limiting the effectiveness of this form of leadership in adverse organisational conditions.

Our study makes several contributions to existing research on ethical leadership. Firstly, by examining the mediating role of disengagement, the study helps provide a better understanding of “why, and not only that”, ethical leadership is related to employee attitudes at work (Ng and Feldman 2015, p. 948). Scholars argue that, the fault for disengagement mostly lies with the organisation and its managers (Pech and Slade 2006; Parkinson and McBain 2013). In particular, by not being honest with employees, not treating them as individuals, not recognising their contributions, and not providing them with feedback, guidance and support, line managers could contribute to employee disengagement (Parkinson and McBain 2013). Ethical leaders care for their employees, support them, and display normatively appropriate conduct in personal interactions to the benefit of subordinates (Brown et al. 2005). In this way, they adhere to the social rules on how supervisors should treat subordinates (Henderson and Argyle 1986). Our study therefore offers a novel theoretical account of how ethical leaders influence the wellbeing and attitudes of their followers, which answers calls for further research on the relationship between ethical leadership and employee wellbeing (Vullinghs et al. 2018).

Secondly, we examine a condition under which ethical leadership is less effective. Barring a few exceptions (Den Hartog and Belschak 2012; Miao et al. 2013; Stouten et al. 2013), little research has examined the conditions that neutralise or undermine the effectiveness of ethical leadership. We suggest that ethical leaders create healthy work environments that are underpinned by clear social rules. However, when clear social rules exist, rule-breaking behaviour becomes more overt. This makes it more obvious that the environment the ethical leader wants to create is not being respected. Moreover, when undermining occurs rarely in the work environment (as one would expect under the supervision of an ethical leader), it can exert a stronger detrimental influence on outcomes (Duffy et al. 2006). Accordingly, we examine whether social undermining is a form of rule-breaking which limits the effectiveness of ethical leadership.

Finally, even though scholars argue that ethical leadership is conceptually different from other leadership styles such as transformational leadership, there are still concerns related to construct redundancy and more scholarly efforts are needed to explicate the empirical distinctness of these closely related forms of leadership (Ng and Feldman 2015; Hoch et al. 2018). This study investigates whether ethical leadership accounts for significant incremental variance in disengagement and employee attitudes beyond the impact of transformational leadership. This, besides controlling for neuroticism, which is an important personality predictor of work-related states and attitudes, enhances the robustness of the study findings.

Theoretical Framework

Ethical Leadership, Disengagement, and Employee Attitudes

Ethical leadership involves “the demonstration of normatively appropriate conduct through personal actions and interpersonal relationships and the promotion of such conduct to followers through two-way communication, reinforcement and decision-making” (Brown et al. 2005, p. 120). This style of leadership includes a moral person aspect and a moral manager aspect (Brown and Treviño 2006). The moral person aspect reflects leaders’ traits or qualities such as fairness, integrity, and trustworthiness. Comparatively, the moral manager aspect reflects how ethical leaders promote ethical behaviour in the workplace. Such behaviours include involving followers in decision-making, providing clarity about appropriate conduct and ethical expectations, incentivising ethical behaviours and punishing unethical conduct (Brown et al. 2005; Treviño et al. 2003; Vullinghs et al. 2018). In this respect, ethical leaders treat followers fairly and with respect by demonstrating people-oriented behaviours and care for their needs (Brown et al. 2005; Treviño et al. 2003; Vullinghs et al. 2018).

Ethical leadership is theoretically different from other forms of positive leadership, such as transformational and authentic leadership (Ng and Feldman 2015; Hoch et al. 2018). Contrary to transformational leadership, where the main focus is on role modelling, ethical leadership comprises a transactional component, which involves the use of punishment or discipline for unethical conduct or behaviour (Brown et al. 2005; Stouten et al. 2013). Ethical leadership is also distinct from authentic leadership, wherein leaders focus primarily on relational transparency and self-awareness rather than ethical behaviour (Stouten et al. 2013). Thus, rather than including ethics as an auxiliary or secondary dimension, ethical leadership explicitly emphasizes the moral aspects of leadership (Hoch et al. 2018; Mostafa 2018).

Recent research has shown that ethical leadership is negatively related to turnover intentions, and positively related to job satisfaction and organisational commitment (Ng and Feldman 2015; Demirtas and Akdogan 2015; Bedi et al. 2016; Hoch et al. 2018; Wang and Xu 2019). However, as noted before, a better understanding is still needed of the mediating psychological process through which ethical leadership induces its effects on these outcomes (Ng and Feldman 2015; Wang and Xu 2019). This study proposes that the relationship between ethical leadership and job satisfaction, organisational commitment, and turnover intentions is mediated by disengagement.

Although burnout has been conceptualised in different ways since its inception, there is general agreement that it consists of two main components: high levels of exhaustion and a cynical/distant reaction towards one’s work (Demerouti et al. 2019). The exhaustion component is known as emotional exhaustion, which involves “feelings of being overextended and depleted of one’s emotional and physical resources” (Maslach et al. 2001, p. 399). The cynicism component was originally known as depersonalisation, yet more recently it has been labelled disengagement (Sonnentag 2005). Disengagement is the degree to which a person withdraws or distances from all work aspects (Demerouti et al. 2010). Kahn (1990, p. 64) states that disengaged employees “withdraw and defend themselves physically, cognitively, or emotionally during role performances”. This perspective is echoed by Bakker et al. (2004, p. 84) who state that it involves an “emotional, cognitive, and behavioural rejection of the job”. As a result, disengaged employees not only perceive that their work tasks are routine, but they also conduct tasks in a mechanical manner or engage in withdrawal behaviours (Demerouti et al. 2001).

Limited attention has been directed towards disengagement and its antecedents (Pech and Slade 2006; Hejjas et al. 2019). This is relevant because recently, it has been suggested that engagement and disengagement are “not opposites” and that different factors could drive or inhibit each construct (Hejjas et al. 2019, p. 329). Indeed, as argued by Macey and Schneider (2008), the opposite of engagement is likely to be “non-engagement”, not disengagement. Therefore, whilst it has been documented that ethical leadership is positively linked to work engagement (Chughtai et al. 2015; Demirtas 2015), it cannot necessarily be inferred that it limits disengagement. Nor that the strategies ethical leaders use to promote work engagement are necessarily the same strategies that reduce disengagement. As a result, this study investigates whether ethical leadership is negatively related to disengagement and considers why such a relationship may exist.

Based on Henderson and Argyle’s (1986) social rules theory (SRT), we propose that ethical leadership leads to reduced levels of disengagement and consequently improved employee attitudes. SRT states that in working relationships, shared expectations exist regarding behaviour that should or should not be performed in specific situations (Argyle et al. 1981). These shared expectations are known as social rules, which Henderson and Argyle (1986, p. 260) describe as “behaviour which members of a group or subculture believe should or should not be performed, either in certain situations or in a range of situations”. The theory postulates that violation or non-compliance with these rules is more likely to be associated with reduced wellbeing and negative employee attitudes, whereas rule compliance will be associated with improved employee wellbeing and positive attitudes (Henderson and Argyle 1986).

SRT asserts that there are a number of universal social rules, which are appropriate in every social situation, such as being friendly, polite, respecting privacy, and maintaining eye contact (Argyle et al. 1981). However, some social rules also vary according to context. For example, Henderson and Argyle (1986) proposed a number of social rules that are unique to the relationship between leaders and their subordinates. These include giving clear guidance to subordinates, organising work efficiently, looking after subordinates’ welfare and acting with fairness. These social rules align with the nature of ethical leadership, which involves displaying normatively appropriate conduct in personal interactions to the benefit of subordinates. Ethical leaders care for their employees, support them, treat them fairly, and with respect (Brown et al. 2005). They consolidate “a general, consistent moral character with a focus on organizational or cultural norms, standards, and rule compliance” (Lemoine et al. 2019, p. 151). Therefore, they are more likely to enhance employee wellbeing and reduce disengagement. Previous research provides support for these assumptions. For example, Mo and Shi (2017) found that ethical leadership was negatively related to burnout. Similarly, Chughtai et al. (2015) found that ethical leadership reduced emotional exhaustion. We, therefore, expect ethical leadership to reduce disengagement.

As disengagement involves cognitively, emotionally, and behaviourally distancing oneself from work (Rathi and Lee 2016), reducing or limiting disengagement should alter how employees view their job and organisation. Specifically, we argue that when ethical leaders are able to reduce or limit disengagement, the extent to which employees wish to leave their organisation will also be limited. This is because when attempting to cope with the demands of a workplace, disengaged employees adopt avoidance based coping behaviours, such as withdrawal (Pienaar and Bester 2011; Rathi and Lee 2016). One of the cognitive manifestations of withdrawal involves thinking about quitting ones job (Lachman and Diamant 1987). Therefore leaders who are able to reduce disengagement should in turn limit the extent to which employees think about quitting.

We also contend that reducing or limiting disengagement should be associated with higher levels of job satisfaction and organisational commitment. When ethical leaders are able to maintain low levels of follower disengagement, employees should have more energy to devote to their tasks, which should result in higher levels of job satisfaction as tasks will not seem so monotonous. Disengagement should also be negatively associated with organisational commitment. Previous research has drawn on Conservation of Resources theory (Hobfoll 1989) to explain the relationship between disengagement and commitment. Thanacoody et al. (2014) found that disengagement mediated the relationship between emotional exhaustion and affective commitment. The authors suggested that disengaged employees have less resources and energy to commit to their organisations. As a result, when disengagement is limited, employees can invest energy in their job or exert effort on behalf of the organisation (Sun and Pan 2008; Rathi and Lee 2016). We, therefore, argue that by reducing disengagement, ethical leadership will have an indirect effect on job satisfaction, organisational commitment, and turnover intentions.

Hypothesis 1:

Disengagement mediates the relationship between ethical leadership and job satisfaction, organisational commitment, and turnover intentions.

The Moderating Role of Co-worker Social Undermining

Co-worker social undermining refers to intentional behaviour from co-workers that reduces another employee’s ability to maintain good relationships, success, and a positive reputation at work (Duffy et al. 2002). In developing the construct for the workplace, Duffy et al. (2002) highlighted three core characteristics. Firstly, behaviour is only considered undermining if it is perceived as intentional by the target. This differentiates social undermining from other forms of workplace aggression, such as bullying, incivility, and abusive supervision, which can occur in the absence of ill-intent (Hershcovis 2011). Secondly, social undermining behaviours may not be harmful if they occur rarely, but their impact is cumulative in that they damage relationships in an iterative manner. Thirdly, social undermining is examined from the target’s perspective. Accordingly, there may be perceptual differences between the perpetrator and target over whether behaviour was intended to harm. The nature of undermining behaviour is varied, in that it may be direct (e.g. overt belittling), or indirect (e.g. withholding information). Furthermore, Duffy et al. (2002) differentiated co-worker social undermining from supervisor social undermining, with the former enacted by one’s colleagues and the latter by one’s supervisor.

We draw upon SRT to argue that when co-worker social undermining behaviour is experienced by followers of an ethical leader, the negative relationship between ethical leadership and disengagement is weakened. SRT states that besides social rules that guide the relationship between leaders and their subordinates, there are also rules which govern the relationships between co-workers, including accepting a fair share of the work, helping when asked and seeking to repay debts, favours and compliments. Henderson and Argyle (1986) also confirmed empirically that the common universal rules were highly endorsed for relationships between colleagues, such as not criticising each other publicly and standing up for a colleague when they are not present to defend themselves.

Co-worker social undermining is a particularly appropriate form of workplace aggression to examine as a rule-breaking behaviour for two reasons. Firstly, unlike other forms of workplace aggression, including bullying, incivility, and conflict, social undermining is perceived to be enacted intentionally (Hershcovis 2011). As a result, it is an overt form of rule-breaking behaviour, in that the target perceives that a co-worker has intentionally violated the rules that govern appropriate behaviour. Secondly, most other workplace aggression variables do not specify the source of the mistreatment within their measures (Hershcovis 2011), which means that they may have been enacted by a leader. Co-worker social undermining is explicitly enacted by one’s colleagues, which allows us to determine whether the social rules were broken by a source other than the ethical leader.

We contend that ethical leaders seek to establish work and group contexts where the social rules governing relationships between colleagues are upheld. Ethical leaders shape follower behaviour by using reward and punishment to clarify ethical expectations (Brown and Treviño 2006). Therefore, when social undermining occurs within their work group, one would expect an ethical leader to use transactional leadership principles by punishing the perpetrator. At the same time, ethical leaders will role model appropriate forms of behaviour and reward those that treat colleagues in an ethical manner (Den Hartog 2015). Theoretically, this should mean that social undermining rarely occurs under ethical leaders, and when it does, an ethical leader would intervene to prevent the behaviour reoccurring. Indeed, studies have shown that certain leadership styles, including transformational and transactional leadership are related to decreased levels of workplace aggression (Astrauskaite et al. 2015; Ertureten et al. 2013). However, research on the antecedents of social undermining has shown that there are a number of causal factors which are beyond a leader’s control, including bottom line mentality (Greenbaum et al. 2012) and moral disengagement (Duffy et al. 2012). Therefore it is possible that social undermining will occur under the supervision of ethical leaders (Taylor and Pattie 2014).

There are two potential ways in which social undermining can weaken the negative relationship between ethical leadership and disengagement. Firstly, social undermining can be perpetrated by other employees who are also supervised by the ethical leader. When this occurs, one would expect the ethical leader to intervene to prevent further undermining behaviour. Yet, despite this, the target may still experience heightened disengagement after the incident. This is because, when an act of social undermining occurs under an ethical leader, it is a more flagrant breach of social rules than when it occurs under other forms of leadership. Duffy et al. (2006) showed that the impact of social undermining is stronger when it only occurs rarely in the workgroup. They argued that this occurs partly due to the discordance between-group norms and personal experiences, as perceived violations arose less negative reactions when the group norm is more tolerant of violations (Leung and Tong 2003). This can be explained by fairness theory as employees cognitively compare their own treatment against that of their co-workers (Folger and Cropanzano 1998). If one’s co-workers are also experiencing social undermining, the victim is less likely to feel that the perpetrator could have acted differently, which affects how strongly a person reacts to the treatment. However, when one’s co-workers have not experienced social undermining, the victim is more likely to feel that the perpetrator could have acted according to the social rules set out by the ethical leader. Duffy et al. (2006, p. 108) state that this is important, because “being singled out creates a more mutable and feasible cognitive comparison and a more damaging context for social undermining”. Therefore the victim is much more likely to experience disengagement.

Secondly, social undermining can be perpetrated by other organisational members who are not under the supervision of ethical leaders, or by others more senior than the ethical leader in the organisational hierarchy. This may particularly be the case in large organisations where there are many layers of management. Other organisational members may be supervised by leaders who do not encourage norms of appropriate conduct towards others. Therefore, they may be more inclined to engage in social undermining behaviour towards colleagues, and particularly towards those who they see as out group members (Ramsay et al. 2011). Nonetheless, all organisational members remain bound by the social rules that govern relationships between co-workers, and targets will still perceive social undermining as rule-breaking behaviour. In such situations, the relationship between ethical leadership and disengagement is still likely to be weakened by social undermining, as the ethical leader has not been able to protect their subordinate’s welfare. Therefore the leader/subordinate specific social rule “look after subordinates’ welfare” will have been broken. Indeed, several studies suggest that ethical leaders act to protect their followers (Bhal and Dadhich 2011; Kalshoven et al. 2013b), which means that failure to protect followers from harm will be particularly salient.

When social rules are broken it results in dissatisfaction for the target (Henderson and Argyle 1986).This dissatisfaction is likely to be felt especially strongly by followers of ethical leaders, because these leaders create conditions where followers expect social rules to be upheld. As a result, when rules are violated, the negative relationship between ethical leadership and disengagement is likely to be weakened, because rule-breaking behaviour serves to undermine the leader’s influence and ability to prevent disengagement. In this respect, co-worker social undermining and rule breaking more generally may be seen as leadership neutralizers, which counteract the effectiveness of leadership by making it impossible for the leader to exert influence (Kerr and Jermier 1978). We, therefore, pose the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 2:

Co-worker undermining moderates the relationship between ethical leadership and disengagement, such that the negative relationship between ethical leadership and disengagement will be weaker when undermining is high compared to low.

Based on hypotheses 1 and 2, we posit that when co-worker undermining is high, the mediated relationships between ethical leadership and employee attitudes via disengagement will be weaker.

Hypothesis 3:

Co-worker undermining moderates the indirect relationship between ethical leadership and employee attitudes (job satisfaction, organisational commitment, and turnover intentions) via disengagement, such that the mediated relationship will be weaker under high than low undermining.

Method

Participants and Procedure

Data for this study was collected from nurses working in 49 hospitals in Romania. Access to hospitals was obtained through personal contacts. A representative of each hospital was responsible for distributing the questionnaires to nurses. To minimise the likelihood of common method bias, the survey was administered across three time points. At time 1, nurses rated their direct supervisor’s ethical leadership behaviours, as well as the extent to which they had experienced co-worker undermining from their colleagues. Two weeks later, at time 2, they completed questionnaires measuring disengagement. Subsequently, after another two weeks, at time 3, they completed questionnaires on turnover intentions, job satisfaction, and organisational commitment. As noted by Dormann and Griffin (2015), shorter time lags are methodologically advantageous compared to longer ones. The two-week time lag helped to reduce respondent attrition as well as minimise the influence of contaminating factors that may cover or conceal relationships between variables (Kovjanic et al. 2012a, b).

Out of the 540 questionnaires distributed, 511 were returned at Time 1. At Time 2, 484 nurses took part in the survey (89.6% response rate), whereas 460 completed the survey at Time 3 (96% response rate). Most of the nurses in the final sample were female (77.7%), with an average age of 37.4 years old, and were working in their hospital for an average of 8.8 years. Almost half of them (45%) had a higher education degree.

Measures

The questionnaire was administered in Romanian. Therefore, all items were initially translated from English into Romanian and then translated back into English by a bilingual researcher (Brislin 1980). The original and translated English versions were then compared by another bilingual academic to ensure equivalence of meaning. A pilot study was then administered on eight nurses to test the questionnaire and no major issues were identified. Responses to all items were on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

Ethical leadership. Brown et al.’s (2005) 10-item scale was used to measure ethical leadership. Sample items include “My supervisor disciplines employees who violate ethical standards” and “My supervisor sets an example of how to do things the right way in terms of ethics”. Alpha for the scale was 0.94.

Co-worker undermining. Duffy et al.’s (2002) 13-item scale was used to measure co-worker undermining. Sample items include “Other nurses in the hospital spread rumours about me” and “Other nurses in the hospital talk bad about me behind my back”. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.95.

Disengagement. Four items from the Oldenburg Burnout Inventory (OLBI; Demerouti and Bakker 2008) were used to measure disengagement. The OLBI is composed of two subscales: exhaustion and disengagement. Both subscales include four positively worded items and four negatively worded items. The positively worded items in the disengagement subscale are generally viewed as markers for work engagement (Halbesleben and Demerouti 2005). Accordingly, and since the focus in this study is on disengagement rather than engagement, we used the four negatively worded items. Sample items include “Lately, I tend to think less at work and do my job almost mechanically” and “Sometimes I feel sickened by my work tasks”. Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was 0.77.

Turnover intentions. O’Reilly et al.’s (1991) 4-item scale was used to measure turnover intentions. Sample items include “I would prefer another more ideal job to the one I have now” and “I have seriously thought about leaving this hospital”. Alpha for the scale was 0.93.

Job satisfaction. Seashore et al.’s (1982) 3-item scale was used to measure job satisfaction. Sample items include “In general, I like working here” and “Overall, I am satisfied with my job”. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.92.

Organisational commitment. Six items developed by Allen and Meyer (1990) were used to measure affective organisational commitment. Sample items include “I feel 'emotionally attached' to this hospital” and “This hospital has a great deal of personal meaning for me”. Alpha for the scale was 0.95.

Controls. Transformational leadership and neuroticism were controlled for as previous research suggests that both variables are important predictors of employee burnout and work attitudes (e.g. Judge et al. 2002; Walumbwa and Lawler 2003; Langelaan et al. 2006; Castro et al. 2008; Eckhardt et al. 2016; Hildenbrand et al. 2018). Transformational leadership was measured using four items developed by Podsakoff et al. (1990). These items measured four different facets of transformational leadership: idealised influence, inspirational motivation, individualised consideration, and intellectual stimulation (Bass 1985). Neuroticism was measured using three items from Judge et al.’s (2003) core self-evaluations scale. Cronbach’s alpha for transformational leadership was 0.90 and for neuroticism was 0.81. Nurses’ gender, age, and tenure were not significantly related to disengagement or employee attitudes and were, therefore, not included in the analysis.

Analytic Strategy

A series of confirmatory factor analyses (CFAs) were conducted to assess convergent and discriminant validity. Three indices were used to assess model fit: the comparative fit index (CFI), the Tucker Lewis index (TLI), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). Good fit is achieved when the CFI and the TLI are 0.90 or above, and when the RMSEA is 0.08 or below (Hu and Bentler 1999; Williams et al. 2009).

Nurses were grouped by hospitals and the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) for disengagement, turnover intentions, job satisfaction, and organisational commitment was 0.30, 0.30, 0.20 and 0.29, respectively. This suggests the presence of significant between-group variance. Therefore, the model and proposed hypotheses were tested using generalised multilevel structural equation modeling (GSEM) with STATA. GSEM is a technique that combines the flexibility and power of both Generalized Linear Models and Structural Equation Models in an integrated modeling framework (Lombardi et al. 2017). It simultaneously considers direct and indirect effects of several interacting factors and is ideal for addressing hypotheses with nested data (Preacher et al. 2010; Lombardi et al. 2017). The use of GSEM in this study enabled us account for the clustering or nesting of observations within hospitals.

All relationships were tested simultaneously. Disengagement (i.e. the mediator variable) was regressed on the controls (i.e. transformational leadership and neuroticism), ethical leadership, co-worker undermining and their interaction term (ethical leadership × co-worker undermining). The outcome variables (i.e. turnover intentions, job satisfaction and organisational commitment) were regressed on the control variables, ethical leadership, co-worker undermining, their interaction term and disengagement (Preacher et al. 2007; Hayes 2013). Following the recommendations of Hofmann and Gavin (1998) and Hofmann et al. (2000), all variables were grand mean centred.

Results

Measurement Model

Eight latent factors (i.e. ethical leadership, co-worker undermining, disengagement, turnover intentions, job satisfaction, organisational commitment, transformational leadership and neuroticism) with their 47 items were included in the analyses. The hypothesised eight-factor model had an acceptable fit (χ2 = 3259.01, df = 1006, p < 0.01; CFI = 0.88, TLI = 0.87, RMSEA = 0.070; Hu and Bentler 1999). All factor loadings were greater than 0.60 and significant at p < 0.01 level, suggesting convergent validity (Anderson and Gerbing 1988).

As shown in Table 1, the fit of the eight-factor model (i.e. the baseline model) was significantly better than other alternate models with fewer factors. In particular, the hypothesised model fitted the data significantly better than a seven-factor model which combined ethical and transformational leadership on one latent factor (Δχ2 = 404.32, Δdf = 7, p < 0.01), and a six-factor model which combined job satisfaction, commitment and turnover intentions on one factor (Δχ2 = 1760.33, Δdf = 13, p < 0.01). The baseline model was also significantly better than a five-factor model which combined job satisfaction, commitment, turnover intentions, and disengagement on one factor (Δχ2 = 2221.36, Δdf = 18, p < 0.01) as well as a four-factor model which combined ethical and transformational leadership on one latent factor, and combined job satisfaction, commitment, turnover intentions and disengagement onto another factor (Δχ2 = 2618.32.32, Δdf = 22, p < 0.01).Thus, discriminant validity was evidenced.

Descriptive Statistics

Table 2 shows the correlations between variables as well as the means and standard deviations. As shown in the table, ethical leadership was negatively correlated with disengagement (r = − 0.23, p < 0.01), while co-worker undermining was positively correlated with disengagement (r = 0.43, p < 0.01). Disengagement was positively correlated with turnover intentions (r = 0.55, p < 0.01), and negatively correlated with both job satisfaction (r = − 0.44, p < 0.01) and commitment (r = − 0.30, p < 0.01). None of the correlation estimates exceeded 0.80, which suggests that multicollinearity is unlikely (Kline 2005). Nonetheless, consistent with prior research (Mayer et al. 2012; Kalshoven et al. 2013a; Hoch et al. 2018), transformational leadership and ethical leadership were highly correlated (r = 0.79, p < 0.01).Therefore, to provide further evidence on the distinctiveness of both constructs, the square root of the average variance extracted (AVE) of each construct was compared with the correlation between them (Fornell and Larcker 1981). For both constructs, the square root of the AVE was higher than the corresponding interconstruct correlation estimate (0.84 for transformational leadership and 0.80 for ethical leadership). This confirms that both constructs are conceptually distinct from each other.

Hypotheses Testing Results

Table 3 presents the full results of the mediated moderation model. Hypothesis 1 predicted that disengagement mediates the relationship between ethical leadership and employee attitudes. Ethical leadership was negatively related to disengagement (β = − 0.16, p < 0.05). Disengagement was also positively related to turnover intentions (β = 0.37, p < 0.01) and negatively related to job satisfaction (β = − 0.22, p < 0.01) and organisational commitment (β = − 0.35, p < 0.01). Moreover, the indirect effect of ethical leadership on employee attitudes via disengagement was significant. The indirect effect was negative for turnover intentions (β = − 0.06, p < 0.05, 95% CI − 0.11 to − 0.01) and positive for job satisfaction (β = 0.041, p < 0.05, 95% CI 0.003–0.07) and commitment (β = 0.06, p < 0.05, 95% CI 0.007–0.10). Together, these results suggest that disengagement mediates the relationship between ethical leadership and employee attitudes, providing support for Hypothesis 1. However, since the direct relationship between ethical leadership and employee attitudes was significant (as shown in Table 3), this mediation is partial rather than full or complete.

Hypothesis 2 stated that co-worker undermining moderates the relationship between ethical leadership and disengagement. The interaction term of ethical leadership and co-worker undermining was significant and positive (β = 0.11, p < 0.01). Figure 2 shows this interaction’s simple slope plot following Aiken and West’s (1991) approach. The negative relationship between ethical leadership and disengagement was significant when co-worker undermining was low (β = − 0.299, SE = 0.083, t = − 3.60, p < 0.01) and was non-significant when undermining was high (β = − 0.023, SE = 0.069, t = − 0.34, p > 0.10). This provides support for Hypothesis 2.

Hypothesis 3 predicted that co-worker undermining moderates the indirect relationship between ethical leadership and employee attitudes through disengagement. The indirect relationship between ethical le adership and quit intentions via disengagement was significant and negative when undermining was low (β = − 0.11, p < 0.01, 95% CI − 0.18 to − 0.04) but non-significant when undermining was high (β = − 0.009, p ˃ 0.10, 95% CI − 0.059 to 0.041). The indirect relationship between ethical leadership and job satisfaction via disengagement was significant and positive when undermining was low (β = 0.07, p < 0.01, 95% CI 0.02–0.11) but non-significant when undermining was high (β = 0.005, p ˃ 0.10, 95% CI −0.02 to 0.04). Similarly, the indirect relationship between ethical leadership and commitment via disengagement was significant and positive when undermining was low (β = 0.10, p < 0.01, 95% CI 0.04–0.17) but non-significant when undermining was high (β = 0.008, p > 0.10, 95% CI − 0.04 to 0.06). These results provide support for Hypothesis 3.

Discussion

The first aim of our study was to examine the mediating role of disengagement in the relationship between ethical leadership and employee attitudes. We found that ethical leadership was negatively related to turnover intentions and positively related to job satisfaction and organisational commitment. Moreover, disengagement mediated these relationships. Therefore, when employees perceived that their leader acted in an ethical manner, they reported lower levels of disengagement from their work. In turn, those employees with lower disengagement levels reported greater job satisfaction and commitment, as well as lower turnover intentions.

These results suggest that ethical leaders have a significant role to play in shaping subordinates’ jobs in a manner that prevents detachment. Based on SRT (Henderson and Argyle 1986), we argued that ethical leaders do this by caring for their subordinates, treating them fairly, and complying with the social rules that are unique to the relationship between leaders and followers. It is worth noting that the association between ethical leadership and disengagement was not strong (β = − 0.16). Thus, even though ethical leadership is a significant predictor of disengagement, it is by no means the only predictor. Therefore, future research may wish to consider other antecedents of disengagement and factors that could help minimise it in organisations.

In line with previous research (e.g., Scanlan and Still 2013; Thanacoody et al. 2014; Scanlan and Still 2019), disengagement has been found to be associated with increased turnover intentions, as well as reduced job satisfaction and affective commitment. This suggests that disengaged employees employ avoidance coping mechanisms and distance themselves from both their jobs and organisations (Pienaar and Bester 2011; Rathi and Lee 2016). It is important to note that disengagement only partially mediated the relationship between ethical leadership and employee attitudes. This suggests that there are other potential mediators of this relationship. Motivation and relationship-oriented variables such as work engagement and trust have been tested as mediators in prior research. Other potential mechanisms, such as ethical cognition and awareness, have been proposed and could be considered in future studies (Den Hartog 2015).

The second aim of our study was to examine whether co-worker social undermining limits the effectiveness of ethical leadership. The results indicate that the protective effect of ethical leadership on disengagement disappears when higher levels of co-worker undermining exist within a work unit. We contend that co-worker undermining is a form of social rule-breaking behaviour, which becomes more overt under the supervision of an ethical leader. When social rule-breaking in the form of mistreatment occurs, it most obviously has a negative impact on the recipient. However, it can also influence the workplace attitudes of bystanders, particularly those who are also under the supervision of the ethical leader. If bystanders perceive that their leader has failed to protect the welfare of a subordinate, or feel that the ethical leader is not sufficiently respected to prevent mistreatment, disengagement is likely to occur. This result can be partially explained by the negativity bias (Rozin and Royzman 2001) identified in psychological research, whereby humans give greater weight to negative entities (e.g., co-worker social undermining) than positive ones (e.g., the support of an ethical leader). The negativity bias highlights how negative actions “have consequences which far outweigh the consequences resulting from positive events of the same magnitude” (Palanski et al. 2014, p. 140). Therefore, the positive impact of ethical leadership may not be observed in toxic work environments.

As a result, our study highlights the boundaries of ethical leadership, which is less likely to be effective in organisations where workplace mistreatment is highly prevalent. Interestingly, the research was conducted within hospitals, where mistreatment occurs more readily (Zapf et al. 2011). The higher levels of mistreatment prevalent in healthcare have been attributed to the augmented levels of job demands, organisational change, and emotional labour within this sector (Carter et al. 2013; Zapf et al. 2011). Therefore, for ethical leaders to successfully manage mistreatment in healthcare settings, they need to be supported by initiatives at the organisational level. Cooper-Thomas et al. (2013) found that perceived organisational support and organisational initiatives against mistreatment were negatively correlated with reports of mistreatment. Accordingly, ethical leaders may have more success in combating the impact of mistreatment on disengagement when they work in a supportive organisation that is committed to limiting harassment. Future research could determine whether this is the case.

Practical Implications

The results showing a negative relationship between ethical leadership and disengagement suggest that organisations could benefit from employing human resource practices that help stimulate ethical conduct of leaders. For example, integrity tests could be used alongside questions on ethics during the interview process to assess a managerial candidate’s morality and integrity. Organisations could also train leaders on the ethical requirements of their job and how to deal with ethical issues in the workplace (Mostafa 2018). Rewarding leaders for acting proactively with ethical matters and addressing ethical issues could also help further enhance ethical leader behaviours. However, it is also important for organisations to be aware that the occurrence of social undermining within the workplace can undermine the efficacy of ethical leadership. Therefore, employing and training ethical leaders alone will not be effective when toxic cultures exist within organisations, as the benefits of ethical leadership transpire at low levels of co-worker social undermining. As a result, organisations should look to support ethical leaders by building an ethical infrastructure, which can limit social undermining. An ethical infrastructure involves formal ethical systems, such as “codes of ethics, written procedures for handling complaints, formal training programs, the use of formal sanctions against unethical behaviour, recurrent communication of policies, and formal surveillance of the social work environment” (Einarsen et al. 2017, p. 39). However, they also involve informal ethical signals (e.g., conversations, observations, and socialisation) that demonstrate how employees should behave when unethical behaviour could occur (Einarsen et al. 2017).

Limitations and Future Research Directions

This study is not without limitations. First, despite the time-lagged nature of the study design, causal inferences cannot be made. For example, it is possible that employees who are not satisfied with their jobs, or attached and committed to their organisations, are more likely to be disengaged and distance themselves cognitively, behaviourally and emotionally from their work. The study’s theoretical rationale and previous empirical research provide support for the proposed causal direction. Nevertheless, future research adopting experimental or longitudinal designs could help better gauge casual effects. The second limitation relates to the use of self-reports, which makes the findings susceptible to single source bias. However, it is important to note that recent research has shown that there is no difference between other and self-ratings of leadership (Lee and Carpenter 2018). In addition, most leadership studies rely on follower reports of leader behaviour (Walsh and Arnold 2018). Self-reports are also usually regarded as the best means for assessing social undermining and individual attitudes (Solberg and Olweus 2003; Hildenbrand et al. 2018; Walsh and Arnold 2018). Importantly, the temporal separation of measurements provides additional confidence in the results. Scholars argue that disengagement is usually associated with counterproductive employee behaviours, such as absenteeism (Carter and Baghurst 2014). Therefore, future research may wish to focus on behavioural rather than attitudinal outcomes of disengagement and collect data from multiple sources, such as supervisory ratings of employee behaviours. This could help further allay common method bias concerns. The final limitation relates to the limited generalisability of the results where all data came from nurses working in Romanian hospitals. Future work in other countries and contexts is needed to establish the generalisability of the study findings.

Conclusion

Drawing on SRT, this study examined the mediating role of disengagement on the relationship between ethical leadership and employee attitudes of job satisfaction, organisational commitment, and turnover intentions. The study also examined the moderating role of co-worker undermining on these mediated relationships. All the study hypotheses were supported. Ethical leadership was indirectly related to employee attitudes via disengagement, and these mediated relationships were conditional on co-worker undermining. These results extend our understanding of ethical leadership and demonstrate that it is less likely to be effective when co-worker undermining occurs in the workplace. Thus, organisations should look to support ethical leaders by building an ethical infrastructure, which can limit social undermining.

References

Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Allen, N. J., & Meyer, J. P. (1990). The measurement and antecedents of affective, continuance and normative commitment to the organization. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 63, 1–18.

Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103, 411–423.

Argyle, M., Furnham, A., & Graham, J. (1981). Social situations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Argyle, M., Henderson, M., Bond, M., Iizuka, Y., & Contarello, A. (1986). Cross-cultural variations in relationship rules. International Journal of Psychology, 21(1–4), 287–315.

Astrauskaite, M., Notelaers, G., Medisauskaite, A., & Kern, R. (2015). Workplace harassment: Deterring role of transformational leadership and core job characteristics. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 31, 121–135.

Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Verbeke, W. (2004). Using the job demands-resources model to predict burnout and performance. Human Resource Management, 43(1), 83–104.

Bass, B. M. (1985). Leadership and performance beyond expectations. New York: Free Press.

Bedi, A., Alpaslan, C. M., & Green, S. (2016). A meta-analytic review of ethical leadership outcomes and moderators. Journal of Business Ethics, 139(3), 517–536.

Bhal, K. T., & Dadhich, A. (2011). Impact of ethical leadership and leader–member exchange on whistle blowing: The moderating impact of the moral intensity of the issue. Journal of Business Ethics, 103(3), 485–496.

Brislin, R. W. (1980). Translation and content analysis of oral and written material. In H. C. Triandis & J. W. Berry (Eds.), Handbook of cross-cultural psychology: Methodology (Vol. 2, pp. 349–444). Boston, MA: Allynand Bacon.

Brown, M. E., Trevino, L. K., & Harrison, D. A. (2005). Ethical leadership: A social learning perspective for construct development and testing. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 97, 117–134.

Brown, M. E., & Treviño, L. K. (2006). Ethical leadership: A review and future directions. The Leadership Quarterly, 17, 595–616.

Carter, D., & Baghurst, T. (2014). The influence of servant leadership on restaurant employee engagement. Journal of Business Ethics, 124(3), 453–464.

Carter, M., Thompson, N., Crampton, P., Morrow, G., Burford, B., Gray, C., et al. (2013). Workplace bullying in the UK NHS: A questionnaire and interview study on prevalence, impact and barriers to reporting. British Medical Journal Open, 3(6), e002628.

Castro, C. B., Periñan, M. M. V., & Bueno, J. C. C. (2008). Transformational leadership and followers' attitudes: The mediating role of psychological empowerment. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 19(10), 1842–1863.

Chughtai, A., Byrne, M., & Flood, B. (2015). Linking ethical leadership to employee well-being: The role of trust in supervisor. Journal of Business Ethics, 128(3), 653–663.

Cooper-Thomas, H., Gardner, D., O'Driscoll, M., Catley, B., Bentley, T., & Trenberth, L. (2013). Neutralizing workplace bullying: The buffering effects of contextual factors. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 28(4), 384–407.

Demerouti, E., & Bakker, A. B. (2008). The Oldenburg Burnout Inventory: A good alternative to measure burnout and engagement. In J. R. B. Halbesleben (Eds.), Handbook of stress and burnout in health care (pp. 65–78). New York: Nova Science. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/7cb5/c694cb9ad8c38e63db5d6458e34cd4fef5ce.pdf

Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2001). The job demands-resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 499–512.

Demerouti, E., Mostert, K., & Bakker, A. B. (2010). Burnout and work engagement: A thorough investigation of the independency of both constructs. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 15(3), 209–222.

Demerouti, E., Veldhuis, W., Coombes, C., & Hunter, R. (2019). Burnout among pilots: Psychosocial factors related to happiness and performance at simulator training. Ergonomics, 62(2), 233–245.

Demirtas, O. (2015). Ethical leadership influence at organizations: Evidence from the field. Journal of Business Ethics, 126(2), 273–284.

Demirtas, O., & Akdogan, A. A. (2015). The effect of ethical leadership behavior on ethical climate, turnover intention, and affective commitment. Journal of Business Ethics, 130(1), 59–67.

Den Hartog, D. N. (2015). Ethical leadership. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behaviour, 2(1), 409–434.

Den Hartog, D. N., & Belschak, F. D. (2012). Work engagement and Machiavellianism in the ethical leadership process. Journal of Business Ethics, 107(1), 35–47.

Dormann, C., & Griffin, M. A. (2015). Optimal time lags in panel studies. Psychological Methods, 20, 489–505.

Duffy, M. K., Ganster, D. C., Shaw, J. D., Johnson, J. L., & Pagon, M. (2006). The social context of undermining behavior at work. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 101(1), 105–126.

Duffy, M. K., Scott, K. L., Shaw, J. D., Tepper, B. J., & Aquino, K. (2012). A social context model of envy and social undermining. Academy of Management Journal, 55(3), 643–666.

Duffy, M. K., Ganster, D. C., & Pagon, M. (2002). Social Undermining in the Workplace. The Academy of Management Journal, 45(2), 331–351.

Eckhardt, A., Laumer, S., Maier, C., & Weitzel, T. (2016). The effect of personality on IT personnel’s job-related attitudes: Establishing a dispositional model of turnover intention across IT job types. Journal of Information Technology, 31, 48–66.

Einarsen, K., Mykletun, R. J., Einarsen, S. V., Skogstad, A., & Salin, D. (2017). Ethical infrastructure and successful handling of workplace bullying. Nordic Journal of Working Life Studies, 7(1), 37.

Ertureten, A., Cemalcilar, Z., & Aycan, Z. (2013). The relationship of down-ward mobbing with leadership style and organizational attitudes. Journal of Business Ethics, 116, 205–216.

Folger, R., & Cropanzano, R. (1998). Organizational justice and human resource management. London: Sage.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50.

Greenbaum, R. L., Mawritz, M. B., & Eissa, G. (2012). Bottom-line mentality as an antecedent of social undermining and the moderating roles of core self-evaluations and conscientiousness. Journal of Applied Psychology, 97(2), 343–359.

Halbesleben, J. R. B., & Demerouti, E. (2005). The construct validity of an alternative measure of burnout: investigating the English translation of the Oldenburg Burnout Inventory. Work & Stress, 19(3), 208–220.

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York: Guilford Press.

Hejjas, K., Miller, G., & Scarles, C. (2019). “It’s Like Hating Puppies!” Employee Disengagement and Corporate Social Responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics, 157, 319–337.

Henderson, M., & Argyle, M. (1986). The informal rules of working relationships. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 7(4), 259–275.

Hershcovis, M. S. (2011). “Incivility, social undermining, bullying… oh my!”: A call to reconcile constructs within workplace aggression research. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 32(3), 499–519.

Hildenbrand, K., Sacramento, C. A., & Binnewies, C. (2018). Transformational leadership and burnout: The role of thriving and followers' openness to experience. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 23(1), 31–43.

Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist, 44, 513–524.

Hoch, J. E., Bommer, W. H., Dulebohn, J. H., & Wu, D. (2018). Do ethical, authentic, and servant leadership explain variance above and beyond transformational leadership? A meta-analysis. Journal of Management, 44, 501–529.

Hofmann, D. A., & Gavin, M. B. (1998). Centering decisions in hierarchical linear models: Implications for research in organizations. Journal of Management, 24, 623–641.

Hofmann, D. A., Griffin, M., & Gavin, M. B. (2000). The application of hierarchical linear modeling to organizational research. In K. J. Klein & S. W. Kozlowski (Eds.), Multilevel theory, research, and methods in organizations: Foundations, extensions, and new directions (pp. 467–511). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Hu, L.-T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cut off criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modelling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55.

Judge, T. A., Erez, A., Bono, J. E., & Thoresen, C. J. (2003). The core self-evaluations scale: Development of a measure. Personnel Psychology, 56, 303–331.

Judge, T. A., Heller, D., & Mount, M. K. (2002). Five-factor model of personality and job satisfaction: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(3), 530–541.

Kahn, W. (1990). Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Academy of Management Journal, 33(4), 692–724.

Kalshoven, K., Den Hartog, D. N., & De Hoogh, A. H. (2013a). Ethical leadership and follower helping and courtesy: Moral awareness and empathic concern as moderators. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 62, 211–235.

Kalshoven, K., Den Hartog, D. N., & De Hoogh, A. H. (2013b). Ethical leadership and followers' helping and initiative: The role of demonstrated responsibility and job autonomy. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 22(2), 165–181.

Kerr, S., & Jermier, J. M. (1978). Substitutes for leadership: Their meaning and measurement. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 22(3), 375–403.

Kline, R. B. (2005). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford Press.

Kovjanic, S., Schuh, S. C., Jonas, K., Van Quaquebeke, N., & Van Dick, A. R. (2012a). How do transformational leaders foster positive employee outcomes? A self-determination-based analysis of employees' needs as mediating links. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 33(8), 1031–1052.

Kovjanic, S., Schuh, S. C., Jonas, K., Van Quaquebeke, N., & Van Dick, R. (2012b). How do transformational leaders foster positive employee outcomes? A self-determination-based analysis of employees’ needs as mediating links. Journal of Organizational Behaviour, 33, 1031–1052.

Lachman, R., & Diamant, E. (1987). Withdrawal and restraining factors in teachers' turnover intentions. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 8(3), 219–232.

Langelaan, S., Bakker, A. B., Van Doornen, L. J., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2006). Burnout and work engagement: Do individual differences make a difference? Personality and Individual Differences, 40, 521–532.

Lee, A., & Carpenter, N. C. (2018). Seeing eye to eye: A meta-analysis of self-other agreement of leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 29, 253–275.

Lemoine, G. J., Hartnell, C. A., & Leroy, H. (2019). Taking stock of moral approaches to leadership: An integrative review of ethical, authentic, and servant leadership. Academy of Management Annals, 13, 148–187.

Leung, K., & Tong, K. (2003). Toward a normative model of justice. In S. W. Gilliland, D. D. Steiner, & D. P. Skarlicki (Eds.), Research on social issues in management (emerging perspectives on values in organizations) (pp. 97–120). Greenwich, CT: Information Age Publishing.

Lombardi, S., Santini, G., Marchetti, G. M., & Focardi, S. (2017). Generalized structural equations improve sexual-selection analyses. PLoS ONE, 12(8), e0181305.

Macey, W., & Schneider, B. (2008). The meaning of employee engagement. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 1(1), 3–30.

Maslach, C., Schaufeli, W. B., & Leiter, M. P. (2001). Job burnout. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 397–422.

Mayer, D. M., Aquino, K., Greenbaum, R. L., & Kuenzi, M. (2012). Who displays ethical leadership, and why does it matter? An examination of antecedents and consequences of ethical leadership. Academy of Management Journal, 55, 151–171.

Miao, Q., Newman, A., Yu, J., & Xu, L. (2013). The relationship between ethical leadership and unethical pro-organizational behavior: Linear or curvilinear effects? Journal of Business Ethics, 116(3), 641–653.

Mo, S., & Shi, J. (2017). Linking ethical leadership to employee burnout, workplace deviance and performance: Testing the mediating roles of trust in leader and surface acting. Journal of Business Ethics, 144(2), 293–303.

Mostafa, A. M. S. (2018). Ethical leadership and organizational citizenship behaviours: The moderating role of organizational identification. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 27(4), 441–449.

Ng, T. W., & Feldman, D. C. (2015). Ethical leadership: Meta-analytic evidence of criterion-related and incremental validity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(3), 948–965.

O’Reilly, C. A., Chatman, J., & Caldwell, D. F. (1991). People and organizational culture: A profile comparison approach to assessing person-organization fit. Academy of Management Journal, 34(3), 487–516.

Palanski, M., Avey, J. B., & Jiraporn, N. (2014). The effects of ethical leadership and abusive supervision on job search behaviors in the turnover process. Journal of Business Ethics, 121(1), 135–146.

Parkinson, A., & McBain, R. (2013). Putting the emotion back: Exploring the role of emotion in disengagement. In W. J. Zerbe, N. M. Ashkanasy, & C. E. J. Härtel (Eds.), Research on emotion in organizations: Vol. 9. Individual sources, dynamics, and expressions of emotion (pp. 69–85). Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing.

Pech, R., & Slade, B. (2006). Employee disengagement: Is there evidence of a growing problem? Handbook of Business Strategy, 7(1), 21–25.

Pienaar, J. W., & Bester, C. L. (2011). The impact of burnout on the intention to quit among professional nurses in the Free State region - a national crisis? South African Journal of Psychology, 41(1), 113–122.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Moorman, R. H., & Fetter, R. (1990). Transformational leader behaviours and their effects on followers trust in leader, satisfaction, and organizational citizenship behaviours. Leadership Quarterly, 1, 107–142.

Preacher, K. J., Rucker, D. D., & Hayes, A. F. (2007). Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 42, 185–227.

Preacher, K. J., Zyphur, M. J., & Zhang, Z. (2010). A general multilevel SEM framework for assessing multilevel mediation. Psychological Methods, 15(3), 209–233.

Ramsay, S., Troth, A., & Branch, S. (2011). Work-place bullying: A group processes framework. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 84(4), 799–816.

Rathi, N., & Lee, K. (2016). Emotional exhaustion and work attitudes: Moderating effect of personality among frontline hospitality employees. Journal of Human Resources in Hospitality and Tourism, 15(3), 231–251.

Rozin, P., & Royzman, E. B. (2001). Negativity bias, negativity dominance, and contagion. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 5(4), 296–320.

Scanlan, J. N., & Still, M. (2013). Job satisfaction, burnout and turnover intention in occupational therapists working in mental health. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 60, 310–318.

Scanlan, J. N., & Still, M. (2019). Relationships between burnout, turnover intention, job satisfaction, job demands and job resources for mental health personnel in an Australian mental health service. BMC Health Services Research, 19(62), 1–11.

Seashore, S. E., Lawler, E. E., Mirvis, P., & Camman, C. (1982). Observing and measuring organizational change: A guide to field practice. New York: Wiley.

Solberg, M. E., & Olweus, D. (2003). Prevalence estimation of school bullying with the Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire. Aggressive Behavior, 29, 239–268.

Sonnentag, S. (2005). Burnout research: Adding an off-work and day-level perspective. Work & Stress, 19, 271–275.

Stouten, J., van Dijke, M., Mayer, D., De Cremer, D., & Euwema, M. C. (2013). Can a leader be seen as too ethical? The curvilinear effects of ethical leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 24, 680–695.

Sun, L. Y., & Pan, W. (2008). HR practices perceptions, emotional exhaustion, and work outcomes: A conservation-of-resources theory in the Chinese context. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 19(1), 55–74.

Taylor, S. G., & Pattie, M. W. (2014). When does ethical leadership affect workplace incivility? The moderating role of follower personality. Business Ethics Quarterly, 24(4), 595–616.

Thanacoody, P. R., Newman, A., & Fuchs, S. (2014). Affective commitment and turnover intentions among healthcare professionals: The role of emotional exhaustion and disengagement. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 25, 1841–1857.

Treviño, L. K., Brown, M., & Hartman, L. P. (2003). A qualitative investigation of perceived executive ethical leadership: Perceptions from inside and outside the executive suite. Human Relations, 56(1), 5–37.

Vullinghs, J. T., De Hoogh, A. H. B., Den Hartog, D. N., & Boon, C. (2018). Ethical and passive leadership and their joint relationships with burnout via role clarity and role overload. Journal of Business Ethics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-018-4084-y.

Walsh, M. M., & Arnold, K. A. (2018). Mindfulness as a Buffer of Leaders’ Self-Rated Behavioral Responses to Emotional Exhaustion: A Dual Process Model of Self-Regulation. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 2498.

Walumbwa, F. O., & Lawler, J. J. (2003). Building effective organizations: Transformational leadership, collectivist orientation, work-related attitudes and withdrawal behaviours in three emerging economies. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 14(7), 1083–1101.

Wang, Z., & Xu, H. (2019). When and for whom ethical leadership is more effective in eliciting work meaningfulness and positive attitudes: The moderating roles of core self-evaluation and perceived organizational support. Journal of Business Ethics, 156, 919–940.

Williams, L. J., Vandenberg, R. J., & Edwards, J. R. (2009). Structural equation modeling in management research: a guide for improved analysis. Academy of Management Annals, 3(1), 543–604.

Zapf, D., Escartin, J., Einarsen, S., Hoel, H., & Vartia, M. (2011). Empirical findings on prevalence and risk groups of bullying in the workplace. In S. Einarsen, H. Hoel, D. Zapf, & C. L. Cooper (Eds.), Bullying and harassment in the workplace (pp. 75–106). London: Taylor and Francis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mostafa, A.M.S., Farley, S. & Zaharie, M. Examining the Boundaries of Ethical Leadership: The Harmful Effect of Co-worker Social Undermining on Disengagement and Employee Attitudes. J Bus Ethics 174, 355–368 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-020-04586-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-020-04586-2